Introduction

Variations of sex of characteristics (VSC) refer to bodily attributes that cannot be classified as typically male or female [

1]. As such they may require collaborative care from multiple care providers [

2]. In 2006 the Chicago consensus statement was introduced to improve the care for people with VSC and their parents [

3]. The consensus advocated for long-term multidisciplinary care, psychosocial support, complete disclosure of medical diagnosis and treatment, caution against early cosmetic surgery and introduced new terminology [

3,

4]. It indicated that multidisciplinary teams should educate other health care professionals involved in the care for people with VSC and their parents and develop a plan for care that should be patient centered [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Yet, the consensus statement did not result in the complete change of medical practice as the evidence suggests that surgeries continued [

8,

9] the provision of multidisciplinary care has not been adequately implemented [

10,

11] and the terminology was met with critique by the intersex movement and some medical professionals [

12,

13,

14].

The consensus statement also briefly stated that one of the tasks of multidisciplinary teams is to organize the transition of care from pediatric to adult [

3]. Yet, ever since 1980s the health care professionals failed to provide transition of care for people with VSC [

15]. The consensus update added that people with VSC share challenges in accessing adult care with other people with chronic conditions [

7]. Transition of care is not defined in the consensus statement as it is mentioned in one brief sentence. However, in the research on adjustment from pediatric to adult care transition of care is defined as a process that includes services aimed at planned and coordinated shift between pediatric and adult care for young people with chronic conditions[

16,

17,

18]. Despite the growing need and professional consensus standards for transition of care, the evidence suggests there is still a lot room for improvement[

18]. Adults with VSC have health issues that have been caused or aggravated by medical interventions[

19]. The research has identified multiple barriers to the adequate transition of care: lack of training on adolescent health care, protentional diffusion of responsibility among pediatric and adult care providers, the complexity of health care conditions, lack of communication between pediatric and adult health care providers, inclusion of adolescents and young adults in the transition process that is meaningful to them, lack of planning and coordination of services as well as lack of evidence to guide the development of transition of care [

18,

20,

21,

22]

The few recommendations on transition of care for adolescents and young adults with VSC that were published in the years between the consensus and its update in 2016 stipulated that the transition of care is a multiple-year process that requires a plan and review for each person with VSC according to their variation and needs, assessment of readiness for the transition and assistance in guiding and education a person with VSC and their family [

15,

23,

24,

25]. Furthermore, the recommendations highlighted the importance of continuous collaboration between pediatric multidisciplinary team, parents, peer support groups and adult providers who should be involved in the care as early as possible, that adult providers should have good communication skills and be well-versed in issues surrounding care for people with VSC. These recommendations also pointed out that transition is a process that involves a shift in care approach and it should start at the age of 12-13 year and be finished around the age of 25, whilst the transfer is a step in which a patient stops seeing a pediatric health care professional and makes an appointment with adult care provider [

15,

24].

The consensus update also highlighted the reasons for lack of appropriate transition of care: adolescents and young adults avoid care providers due to poor outcomes of the past medical treatments, non-disclosure of diagnosis and medical treatment in the past and anxiety related to sexual and romantic relations [

7]. Moreover, only a few other publications identified additional barriers for transition of care as follows: a lack of trained providers in the adult care for people with VSC and their parents, a lack of priority and finances for multidisciplinary care in healthcare systems that VSC require, differences in care approaches between pediatric and adult care, a lack of psychosocial support and a ack of data the provision of transition of care [

23,

24,

26].

Little is known how adults with VSC navigate the health care system [

19]. Furthermore, the literature on the transition of care for people with VSC remains scant. There is scarce evidence on the transition of care which points to poor implementation of transitional care [

26,

27] as well as need for research in the field. The aim of the following study was therefore to map out the opinions on practice in transition of care for adolescents and young adults with VSC and their parents based on the focus groups with peer support groups and members of multidisciplinary teams working in care for children with VSC and their parents.

Materials and Methods

Design

The study used an exploratory qualitative design based on mixed focus groups (in terms of professional background) and reflexive thematic analysis [

28]. Reflexive thematic analysis was used, because we wanted to map out the meaning patterns and divergences in viewpoints of the informant about the approaches to care. Semi-structured focus groups interview guide was used to obtain information about the informants’ viewpoints on the composition, collaboration and challenges between peer support groups and members of multidisciplinary teams working in care for children with VSC and their parents.

Data collection and data setting

Six focus groups in five different European countries (Belgium, Germany, Slovenia, Sweden, and United Kingdom) were conducted from May 2022 to February 2023 with members of multidisciplinary teams. The questionnaire guide for focus groups was piloted with a multidisciplinary team. All the focus groups were conducted by the author who is a research fellow with background in sociology and gender studies and three years of experience in qualitative research. The author developed the interview guide based on the scoping review [

29] and additional literature search together with the supervisors. The data on transition of care presented in this paper were taken from the corpus of data collected from the focus group that was too comprehensive to be analyzed in one paper.

The participants were sent the information sheets and informed consent sheets a week before the scheduled time slot for the focus group and were asked to send them signed and filled out to the author. Focus groups lasted from 45 minutes to 75 minutes and all of them were conducted online on Zoom and were audio recorded. All focus groups were conducted on Zoom. On average number of participants in the focus groups ranged from 3 to 4. At the beginning of each session the author would explain to the participants the goals of the focus groups and presented the rules of the discussion. Then the participants would introduce themselves and the reasons why they chose to participate. This would be followed by asking the questions and receiving responses. If there were any unclear answers the author would ask for a clarification or state a follow-up question. At the end of each focus groups the author would give the participants the chance to ask or state questions or concerns that arose during the discussion but might not be addressed. At the end of each session the author would then thank the participants for collaboration and ask them to send the signed informed consent sheet in case they have not done so.

The focus groups were conducted after a pilot study that included a focus group with one of the multidisciplinary teams contacted by the first supervisor and a member of a peer support group. After the pilot study the author reduced the number of follow-up questions in the semi-structured interview guide and reduced the number of the main questions from 8 to 7 to make the focus groups less time consuming and provide less redundant answers.

The final number of participants was 18, among them 16 health care professionals and two peer support members. On average the number of participants in the focus groups ranged from 3 to 4. Not all participants were included in the final selection as 5 respondents could not attend, 2 explicitly decided not to, 2 did not provide informed consent and one decided to leave the focus groups in the beginning of conducting it.

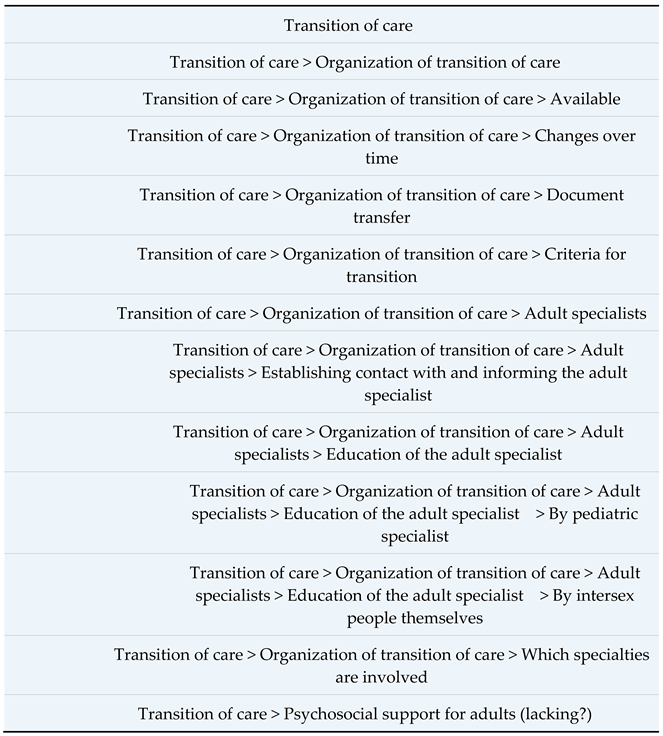

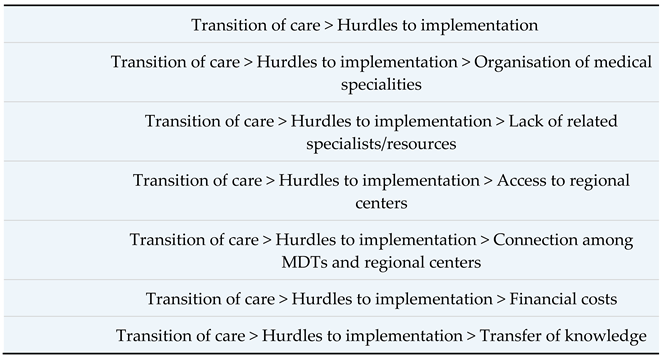

The focus groups were then transcribed and pseudonymized. The transcripts were not sent to the participants due to time constraints. The transcripts were coded with MAXQDA 2020 program using the (following) coding tree (

Table 1). The data were first independently assessed by the author, then by the second supervisor. Afterwards, the author and the second supervisor were joined by the first supervisor to compare and reflect on the assessment which resulted in creating the first draft of the coding tree. The coding tree was slightly adapted after the second reading of the transcripts and making notes on already provisionary themes and subthemes but staying open to changes. The coding tree was designed inductively by extensive reading of the transcripts multiple times and using the notes made while conducting the focus groups by the author. The codes were then qualitatively analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis as the author became familiar with the data he generated the themes as meaning is created in the analysis process [

28]. Firstly, the author focused on the commonalities in participants reflections. Then the author consulted and reflected with the research team on the emerging themes. Secondly, in the next stage the author looked for similarities, differences, and commonalities in the transcribed material to crystalize the three most prominent themes and their sub-themes. The author then read the material again to see how the themes were expressed by the participants. The themes were then illustrated by selection of quotations which were slightly revised to improve on readability. The quotes from focus groups conducted in German were translated by the author themself in English.

Results

The key themes from the focus group data concerned the organization for the transition of care, the criteria for transition, change in the practice, documentation, hurdles to transition and psychosocial support.

Availability of transition of care

Transition of care is available to some extent in all the teams, but the quality and provision varies greatly. The medical specialists in the pediatric multidisciplinary teams involved in transition of care are mainly endocrinologists, urologists, gynecologists, and psychologists, but in the adult care these medical specialties are lacking. The transition process is mostly organized within the department of endocrinology, including the variations which are not endocrinological and it is often pediatric endocrinologists who inform and involve adult endocrinologists to participate already in the team discussions when a child with VSC is born. Research contributors reported that adolescents, young adults, and parents are introduced to transition of care early on. The majority of participants stated that the transition of care has become well incorporated in the team tasks; for example:

We are connected also with adult endocrinologists and they are always invited also to our multidisciplinary team. So sometimes this can be of course, we can discuss these patients that are at the time of transition directly with them at the multidisciplinary team and present them to them. Otherwise we have quite good this transition practice. So that every patient that goes to the adult endocrinologist, this is just general, not just for the DSD patients, but also other rare endocrine disorders that need further follow-ups. So that we make overview for the patient, final overview of his care under ours. And all this is then controlled when they are transferred to adult endocrinology, so that we get an information that the patient came there or something like that. So the this transition was smooth. Sometimes we even joined the patient at the first meeting. (Endocrinologist, team 1)

Criteria for transition

The criteria for transition are multiple and they differ among the teams. In all focus groups the respondents pointed out that transition depends on variation. The respondents mentioned that adolescents and young adults with VSC should be equipped with knowledge about their variation and how to navigate the health care system. The age itself was not always mentioned as one of the criteria for transition, because in some teams, psychological maturity of the individual could be taken as one of the sufficient criteria for transition. In some teams, special hour was devoted to talking about the transition to adult care with the individual and their parents in collaboration with the adult gynecologist or endocrinologist.

So, yeah. Sometimes it's age, but sometimes it's actually maturity. So it's the physical mental maturity of the patient who you'd say, well, actually, I think this boy is ready, or this girl is now ready to be moving on to my colleagues. But we don't do it as like a one off thing. It may well be that the patient comes to that joint clinic on a few occasions for them to be getting prepared to move on. So, they may, perhaps the gynecologist or the psychologist may see them when they're 12,13 at that clinic with the pediatric person, and then as they get older, the people will get to take over the case. (Endocrinologist, team 6)

Change in the practice

There has been an improvement in the provided services as there are centers and specialists that provide care for adolescent and young adults with VSC. In the last two decades the teams have managed to introduce structurally organized transition of care by investing time and resources. Most respondents stated that the transition of care has improved as there are now specialists for adult care and patients are referred to them.

Over the last three years the structures have been well built which then makes every day work much easier, because we know okay, that goes here, that goes there, simply say or write an email and then the care is definitely well provided and we can also support young people right away and don't have to guess or puzzle. (Endocrinologist, team 2)

Documentation

One important part of transition of care that was highlighted time and again among most participants was the documentation of the provided care and its transfer from pediatric to adult care. Children with VSC and their parents in most teams receive the copies of the diagnosis and provided treatment and they are also given a special folder in which they can note their questions, remarks and impressions received during consultations and collaborations with the health care providers in the teams and peer support groups.

We then hand over all the results that we have to the adult endocrinologists, they have them in their files, and then we also make sure to schedule the appointment so that they hand over all their important documents to the young women again get, because that's often the case in childhood. The parents got the letters and then maybe they no longer have them. But we make sure that the young women then have all their documents again, the chromosome analysis, the important ultrasound examinations, that they get everything in their hands and then have them with them. So that already exists for DSD diagnoses, for Turner syndrome, for CAHs and we are still in the process of establishing that for Kleinefelter syndrome, so that we can then also carry it out in a really structured way within a transition consultation. (Endocrinologist, team 3).

Barriers for implementation

The biggest obstacle in good quality of transition of care mentioned in all the focus groups was lack of related adult specialists. Adult specialists for VSC are not available in every hospital which becomes a problem for adult people with VSC who move to another town. Adult people with VSC then either stay in touch with the pediatric specialists or are left without a specialist and seek them for a long period of time as was pointed out by many participants.

Although the number of specialists, of adult specialists interested in Turner DSD-pathology is rare, very rare. Adult specialists have rarely interest in these conditions, there are so many other pathologies that are much more frequent, that you may be grateful if you find somebody who is interested and has some experience and knows how to take care of adult patients. (a member of a peer support group, team 5)

Other hurdles to transition of care included poor transfer of knowledge between pediatric and adult care providers, which forces adolescents and young adults with VSC to educate the care providers themselves, and lack of financial resources for adult care which was mentioned in relation to access MDT that are usually available only in university health care hospitals. A lack of local services can be very problematic, as the following quote indicates:

In the DSD field, we try to make contacts there whenever possible. But now another young person has showed up and they moved to another town. It's also a phase of life when people then leave their surroundings. And this young person called me from [town] saying that they don't know anyone there, I almost said I was sorry. But that means that I can - only help him very subconsciously and indirectly and cannot really find anything on the spot. (Endocrinologist, team 2).

Another obstacle that stood out in relation to the transition of care was psychosocial support, which is severely lacking in almost all adult teams, because there are very few psychosocial providers. There is a lack of knowledge of adult psychosocial care among health care professionals which leads to lack of empowerment for adolescents and young adults with VSC as it was mentioned by some respondents:

There is no program, but organizationally I'm in the medical psychology unit and adult patients, when they transition to adult care, they can get referred to medical psychology, which has a clinic of its own… I have some adult patients that speak about not feeling empowered enough because they are still trying to grasp the diagnosis themselves, and once they're through that stage, they don't feel ready for the leaving groups.

(psychologist, team 4).

Overall, the key themes from this study concern resources and psychosocial support. The multidisciplinary teams have managed to organize the transition of care as part of their tasks, but not adequately as the transition of care still lacks in provision of psychosocial support and adult specialists, especially those patients whose variation is not addressed by endocrinologists.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that transition of care has been implemented to some degree in the last two decades as there are teams that have organized transition of care. But the lack of resources and psychosocial support represent the most serious hurdles to proper transition of care that came out of focus groups, and findings suggest inadequately implemented transition of care. The lack of resources that found in this study has been indicated already in previous studies [

27,

30]. There are no continual examinations, centers of care are remote and practitioners in adult care lack knowledge on variations of sex characteristics [

27,

30,

31]. The findings in this study are consistent with general studies on transition of care in adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions which indicated insufficient coordination of services and lack of recognition who should take responsibility for the transition [

20,

21]

Our study went further and showed that the issues with transition of care are even deeper as there are often simply no adult care providers for adolescents, young adults, and older people with VSC. What is more, even if there are adult care providers this no guarantee that the care will be provided as they lack knowledge and expertise which means that adolescents, young adults, and older people with VSC must educate their adult care provider to ensure the care is provided in the first place. This represents an emotional burden for the adolescents, young adults, and older people and in some cases also engaged parents and families who try to support the young person into adulthood as they must often repeatedly share their medical history with different care providers. This is consistent with previous studies that showed how the burden on adults with VSC to educate their adult practitioners develops feelings of frustration and stress[

30,

31]. But it is, sadly, not uncommon in the transition process as the research in the past highlighted that medical professionals receive minimal training on adolescent health care and transition of care and that transition process is not centered around adolescents needs [

18,

22].

This is consistent with findings from the study by Sanders and Carter [

32] in which young women with CAH reported inadequate support to address their emotions. Even though in some teams the communication between pediatric and adult care providers is established from the start, there is still a of room for improvement to prevent repeated sharing of medical history on the patient’s behalf [

33]. The practitioners could avoid major barriers in overall transition of care to ensure the suitable provision by employing more adult care practitioners, establishing a relationship between adult providers, adolescents and young adults; and developing skills in adolescents/adults to navigate the health care system that is quite challenging for people with rare conditions such as VSC as is stated in the literature [

34].

The results in this study confirmed the differences in care approaches between pediatric and adult care providers already mentioned in the literature [

5,

24,

31]: the pediatric care delivered by multidisciplinary teams and individually oriented adult care, lack of multidisciplinary teams in the adult care and almost no attention for psychosocial support. The latter was said to be largely missing in the transition to adult care as almost all the participants mentioned in the focus groups, even though the research on transition of care emphasizes the importance of psychosocial services in the transition of care[

18]. This finding is all the more striking and makes the push for psychosocial support in the adult care vital since the literature on quality of life in adult people with VSC revealed that they experience a range of serious health issues such as depression, anxiety and suicidality [

19,

35,

36] in comparison to general population, feel stigma around their bodies and sexuality [

37,

38,

39] and age in poor psychosocial conditions [

19]. Lack of psychosocial support in this study is mirrored by previous studies on service experience of young people with VSC which showed that psychosocial support is not provided even when it was asked for [

32] and that young people with VSC are least are often referred to because of psychosocial reasons[

27]. The lack of psychosocial support leaves adults with feel abandoned and exacerbates stigma and shame [

31]. What is more there is an unaddressed need in the adult care for those adult people with VSC who seek gender transition due to gender misassignment early in life.

There is yet another more important duty on the behalf of health care professionals to improve transition of care for young adults and older people with VSC and that is the history of medical treatment people with VSC. The medical practice prior to Chicago consensus statement had poor surgical outcomes [

9] and deleterious effect on mental health of people with VSC [

40] since it did not abide by bodily autonomy, truthful informed consent policies and seriously lacked psychosocial support [

13]. The need and ethical imperative for transition of care is therefore more urgent for the older and aging population of people with VSC who are in need for medical treatment either due to medical harm or simply because their health is deteriorating and because they need psychosocial support to help them undo the secrecy, stigma, and shame they were told to live with in the past.

Limitations

The results of the study cannot be generalized since the sample was not representative. The drop-out of some participants also significantly influenced the final sample and the material used for the analysis. The sample is also biased as the recruiter received response from the team members whom they already met in person and felt like they can be trusted.