1. Introduction

Hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that can arise on the skin or in internal organs. They are caused by stem cells that, in response to various stimuli, can proliferate and differentiate into a variety of cell lines, including mesenchymal stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells, neuroglial stem cells, and hematopoietic stem cells [

1,

2].

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) has proposed various classifications of these vascular conditions, stressing the difference between “real” hemangiomas and vascular malformations, which are localized anomalies of vascular morphogenesis brought on by malfunction in embryogenesis and vasculogenesis that increase as a result of endothelial cell hyperplasia [

3].

Hemangiomas are the most frequent benign pediatric soft tissue tumors, affecting 12% of this population. The head and neck region accounts for 60% of cases, with the trunk following at 25% and the extremities at 15%; the genital area is rarely affected. They are classified as Congenital Hemangiomas (CHs) and Infantile Hemangiomas (IHs). CHs account for 30% of all hemangiomas, at birth they are clinically evident as completely grown lesions that either involute quickly in the first year of life or may never display involution, and they have equal male and female prevalence. On the contrary, IHs are more common (70%), occur at 2-8 week of age, grow rapidly for about 6-12 months and, then, have a slow involution with 90% of them disappearing by the age of 9 years.

For IHs the main risk factors are represented by: low birth weight loss, multiple pregnancies, female sex, white population, higher maternal age, progesterone therapy and positive family history.[

4] While they are typical of childhood, and usually undergo involution, vascular malformations are instead typical of adulthood and are divided into: arterial, venous, capillary, lymphatic or mixed. The most prevalent of them are venous malformations (VMs), once known as "cavernous hemangiomas" [

3,

5].

Infantile hemangiomas are classified by depth:

− Superficial: located at the level of the superficial dermis, usually red;

− Deep: located in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue, usually blue;

− Mixed

and the anatomical aspect:

− Localized: well-defined lesion, that seem to originate from a central point

− Segmental: involving a plaque-like anatomical region, usually measuring > 5 cm;

− Indeterminate: neither clearly localized nor segmental;

− Multifocal: present at disparate sites.

Hemangiomas are also classified into high and low risk, taking into account the clinic and characteristics of the lesions. In details:

− Life threatening: located along the respiratory tract, can cause obstruction and death due to respiratory complications;

− Functional impairment: located along the oral fissure or affecting the eyes, can be the cause of a functional limitation;

− At risk of ulceration;

− Associated with structural anomalies (ex. lumbar syndrome);

− Hemangiomas which, due to their location, represent a disfigurement for the patient [

6].

Hemangiomas are usually clinically silent lesions, that are occasionally find during the gynecological examination, even if sometimes they can give rise to profuse bleeding that requires medical intervention [

1].

Due to their rarity, there isn't a treatment that is widely accepted; nowdays the main options are represented by propranolol, topic corticosteroids, and surgical excision, followed by latertherapy, embolisation, radiotherapy, intermittent pneumatic compression and continuous compression in the treatment of symptomatic haemangiomas. Also, expectant management could be considered in asymptomatic lesions. Therefore, the symptoms produced, the localization of the lesion, and the institution's level of experience handling such cases all influence the management [

7].

The aim of this study was to conduct a review of literature to analyze the clinical characteristics of pediatrics vulvovaginal hemangiomas, in order to help clinicians in the diagnosis, management and treatment of this lesions. In addition, we collected a series of interesting clinical cases of patients who referred to our clinic, with related iconography, in order to provide further help in the diagnostic process.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a search of the medical literature regarding the relationship between vulvovaginal hemangiomas and childhood consulting PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, and Web of Science. The following keywords were used in combination as a search strategy: “vaginal hemangiomas”, “vulvar hemangiomas” “low genital tract hemangiomas”, “infant”, “childhood”.

We sorted out all articles published between October 2021 and April 2023. Only articles written in English were considered. Two authors (L.M. and A.I.V.) evaluated the references separately, to include the literature data in the review. The papers were then chosen based on the abstract and, afterwards, on the entire text content. Following the removal of articles not published in English, 33 publications were screened by title and/or abstract. Unneeded and duplicate papers were excluded from the analysis. Eventually, a total of 9 papers were deemed appropriate using the search approach and, so, analyzed.

Studies were considered eligible if they fulfilled the following criteria: (I) the association between vaginal and vulvar hemangiomas and childhood; (II) the significance and characteristics of vaginal hemangiomas in infancy.

The exclusion criteria were the following: (I) conference abstracts, editorials, and preprint manuscripts; (II) multimedia; (III) experimental papers with animal experiments as a foundation for the findings. To ensure validity and avoid any selection, performance, detection, attrition, or reporting bias, two researchers (L.M. and A.I.V.) independently assessed the risk of bias for each chosen study in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Finally, data analysis and retrieval were done independently by each researcher.

3. Results

The current work is structured into two sections: the clinical presentation of our cases is reported in the first section, while the results of the literature review are highlighted in the second section. The analysis of the data has highlighted that the present literature about vulvovaginal hemangiomas in childhood and adolescence is limited to a small number of case reports, reviews, or clinical retrospective or prospective papers.

3.1. Case Series

We present three cases of hemangiomas of the lower genital tract of patients who referred to the "Vulvar Pathology Study Center" in Rome, Italy. All patients were asked for informed consent for the collection of images and clinical data.

3.1.1. Case 1

A 18-year-old girl presented with a large hemangioma extending from the pubic region to the left labia majora (

Figure 1A), involving the labia minora bilaterally as evident on visit and inspection of the vulvar vestibule (

Figure 1B). It, then extends to the left perianal area (

Figure 1C), the left buttock and the posterior region of the left thigh and back (

Figure 1D). The girl did not present any related symptoms.

3.1.2. Case 2

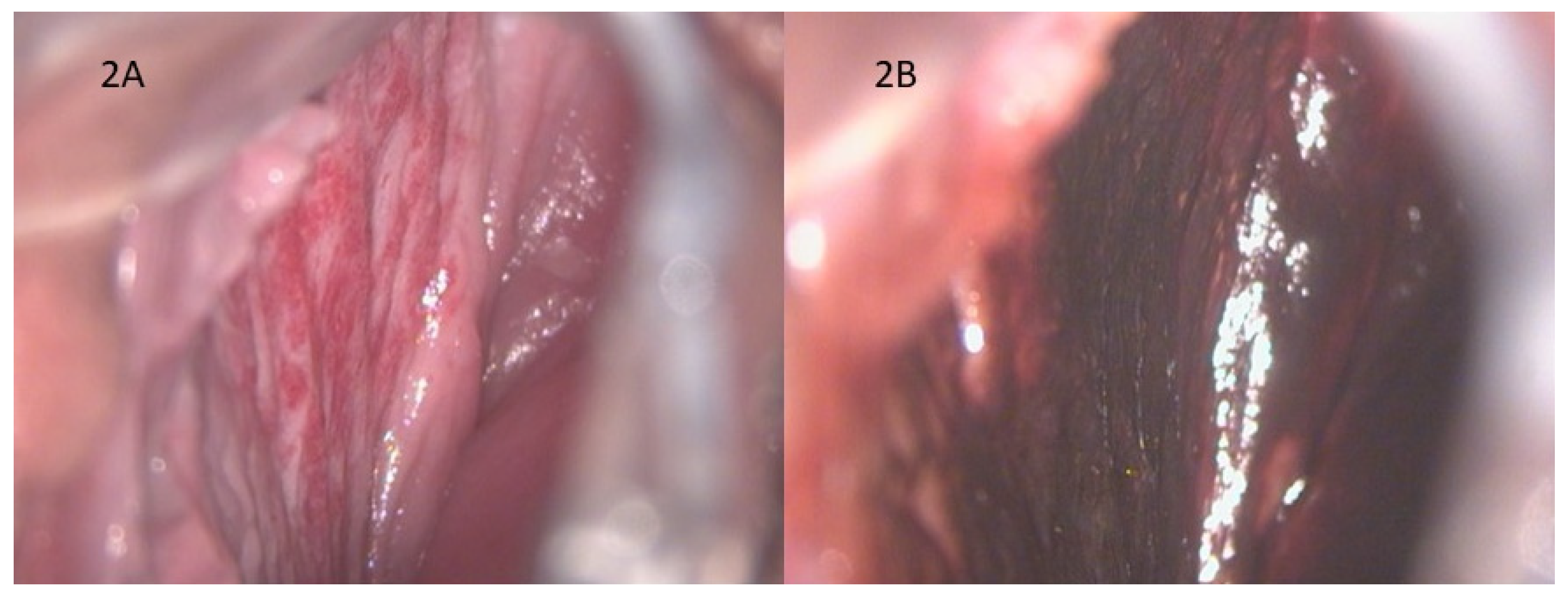

A 17-year-old girl came to our office reporting significant vaginal blood loss, not related to sexual intercourse. A complete gynecological examination was carried out, followed by a colposcopic examination which highlighted the presence of hemangioma of the right vaginal wall (

Figure 2A).

Figure 2B shows the negative result of the Lugol test: we can’t appreciate any areas of alteration, and the trophism of vaginal mucosa is well-preserved.

3.1.3. Case 3

A 17-year-old patient came to our outpatient clinic complaining of significant blood loss and intimate discomfort. In agreement with the patient, we proceeded to the gynecological examination with a speculum which revealed a hemangioma of the cervix, as shown in

Figure 3. No additional hemangiomas were evident elsewhere in the body.

3.2. Literature Review

The main characteristics of the 9 papers retrieved and examined are summarized in

Table 1. They result from the investigations conducted with the indications exposed in Materials and Methods.

In the papers analyzed, patients ranged in age from 5 months to 13 years old, with an early onset of symptoms, when present. Among the 9 cases, 1 was asymptomatic and the hemangioma was incidentally diagnosed, 3 reported swelling in the genital area, and 5 presented with vaginal bleeding.

While mild or no symptoms were associated with vulvar localization, moderate to severe symptoms were associated with 2 cases of vaginal hemangiomas, one of which extended to the cervix, with one intrauterine localization, one cervical and one of the bladder that presented also with hematuria. The last 2 cases, described by Russel et al. and Ganti et al, required blood transfusions due to the significant blood loss. In only one case concomitant abdominal pain and constipation were present, but targeted diagnostic investigations were performed and found to be negative.

Concerning the treatment options, both surgical and medical therapy were used, while non cases of laser therapy were retrieved. In one case, Russel et al decided to administer prednisolone in a 2-year-old patient with bladder hemangioma, which led to its resolution in 10 days. However, this was the only time we found a relapse after 2 and 3 years, that were treated with local prednisolone and, then, with surgery with the final resolution of symptoms. Other 3 patients, one with highly vascularized focal intrauterine intracavitary lesion, and two with superficial vulvar hemangiomas, benefited of surgical excision with a complete and immediate recovery. In one patient with mild to moderate vaginal bleeding, Jackson et al. settled for an expectant management with a decrease in symptoms and size of the lesion after 2 months; on the contrary, Talon et al. tried a conservative management in a 9-year-old girl with moderate to severe vaginal bleeding from a vaginal and cervical hemangioma, but after 2 months the clinical picture was still severe and associated with pelvic pain, so that a diagnostic laparoscopy was needed. The asymptomatic 11-year-old girl with vulvar hemangioma was followed over time and has had no other problems.

4. Discussion

Haemangiomas are an aberrant proliferation of blood vessels, which may occur in any vascularized tissue of the body. They are frequently discovered in the subcutaneous and dermal tissues, while they are very uncommon in the female genital tract. When present, these benign tumors are the most prevalent in infants and often resolve by adolescence [

7].

Their pathogenesis is not clear to date, but an important role is certainly played by pluripotent stem cells which respond incorrectly to stimuli supplied by hypoxia and by the renin angiotensin aldosterone system [

4]. A placental origin has also been hypothesized because the expression of placental markers has been observed in the endothelium of infantile hemangiomas [

16].

In this regard, many studies have found, in IHs, a GLUT-1 (Glucose transporter-1) positivity. GLUT-1 is a sensitive and specific marker for IH that cannot be identified in other vascular anomalies that fall under the histopathological differential diagnosis, for example varices, arteriovenous malformations, and lymphatic malformations. Additionally, proliferating and involuting IH are characterized by other unspecific markers, such as VEGF, bFGF, collagenase IV, urokinase, which aren’t expressed by other vascular malformations [

3,

12].

In non-cutaneous cases, when inspection and vaginoscopy aren’t conclusive, imaging can complement the diagnosis, based on different clinical pictures. For example, Ralph et al. performed a CT scan and a MRI to assess the cause of vaginal bleeding, thus discovering a highly vascularized intrauterine intracavitary lesion. Likewise, Russel et al., in a 2-year-old child with vaginal bleeding and hematuria, after ruling out a possible vaginal origin of the problem with a negative vaginoscopy, they executed a cystoscopy, thus making a diagnosis of hemangioma of the bladder.

While most of these benign tumors are usually indolent, in some cases they might present with severe bleeding or result in emotional or functional impairment. For this reason, it is important to know that various treatment options are available and, since spontaneous regression of the tumor is possible, expectant management should be an option [

7].

Nowadays, the basis of systemic therapy is propranolol, a non-selective beta blocker, on a level of evidence 1A. Before starting treatment, it is advisable to carefully analyze the patient's clinical history and vital signs. In children born pre-term, with low birth weight or a history of hypoglycemia, it is recommended to perform a basal blood glucose measurement [

17,

18]. Since the medication is contraindicated in situations of bundle branch blockages and arrhythmias, electrocardiogram should be executed in individuals with positive anamnestic history of cardiac or connective tissue disorders. The molecule functions on multiple fronts, including vasoconstriction, prevention of angiogenesis, induction of apoptosis, inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis, and modulation of the renin-angiotensin system, though the exact rationale for its usefulness is unclear. The recommended dose is 2 and 3 mg/kg per day in patients at risk, however, it is recommended to start with 1 mg/kg per day and evaluate the body's response before bringing the drug to target.[

19]

Other useful beta blockers are atenolol and nadolol, these have the advantage of fewer side effects and longer half-life compared to propranolol. Atenolol is a selective β1-antagonist with a lower risk of bronchospasm and hypoglycemia. The recommended dose 1 mg / kg per day in IH [

20].

The difficulty with these medications is that they increase the release of nitric oxide and nitrogen peroxide at the hypothalamus level, thus they can have detrimental neurological consequences; in fact, further pharmacokinetic studies are needed [

21].

Corticosteroids have long been the only therapy used for hemangiomas; their use was gradually reduced when beta blockers were introduced. To date, however, in the event that there are contraindications to the use of propanol, prednisone and prednisolone should be administered. The recommended initial dose is 2-3 mg/kg/day, and the duration of treatment varies from 9 to 12 long cycles [

22]. In case of high-risk hemangiomas, the combined therapy of propanol and corticosteroids can be chosen [

23]. In our literature search 2 out of 9 cases were treated with propranolol with a stability or reduction of the lesion ad one case with prednisolone, resulted in two recurrences which, at the end, required a surgical treatment.

Besides this first-line therapy, there are other molecules, like captopril and sirolimus, whose mechanism of action in this area has yet to be further investigated [

19].

In the past, lasers were somewhat helpful for IH primary care. However, the introduction of propranolol as a major treatment for IH has narrowed the scope of laser control to very specific uses. For instance, a common use is the intralesional application of the Nd:YAG laser for medically refractory lesions, or of the PDL laser for persistent cutaneous lesions that do not completely resolve with pharmaceutical care, either alone or in combination with beta blockers as combined primary management. Many studies have demonstrated that the combination of laser and a beta blocker (ex. propranolol) systemically has proven to be superior to monotherapy [

24,

25].

In our review, no cases of laser therapy were retrieved. This could be justified by the fact that, except for one study, all the other are pretty recent and, as the literature suggests, since the advent of propranolol and other medical therapies, laser treatment has taken a back seat. In addition, it should be kept in mind that it is a more expensive procedure and not found in all centers.

Eventually, for superficial hemangiomas topical treatment is also recommended, specifically the use of thymodol maleate 0.5% applied twice daily, which has replaced the use of corticosteroid [

26].

Thymodol is a non-selective beta blocker, that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of superficial hemangiomas even more than propanolol and with fewer adverse effects [

27].

Even if medical therapy remains the first choice, sometimes procedural interventions are needed.

To treat focal, bulky IH, intralesional injection of corticosteroids (triamcinolone and/or betamethasone) or bleomicin may be utilized as an addition to oral β-blockers, or in non-responders.

Cryotherapy has proven to be effective in both superficial and deep IH.

Surgery is usually recommended for life or function threatening IH, for example hemangiomas of the airways or causing massive bleeding, or in cases of unsuccessful or contraindicated medical therapy. It is based on the fact that hemangiomas usually have an expansive rather than an invasive growth, thus displacing the neighboring structures; this allows the surgeon to radically remove them. Sometimes, when there are limit situations with not controlled bleeding or with expansile masses causing organ compromise or cardiac failure, embolization may be an option. In our cases, surgical excision was used both as a second line treatment after the failure of medical therapy, and as a first line treatment in a child with intrauterine hemangioma causing significant vaginal bleeding and in a 13-year-old with a circumscribed vulvar lesion [

19].

5. Conclusions

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of childhood, and the most frequent subtype are Infantile hemangiomas (IH) accounting for 70% of the total. Despite their being common, genital localization is rare. When the doubt of hemangioma arises, it is essential to exclude other pathologies which may enter in the differential diagnosis, since prognoses and therapeutic methods are different.

Hemangiomas are mostly asymptomatic and resolve with age, but sometimes they can result in local tissue damage, ulceration, infection, bleeding, functional impact, and pain. Because of the rarity of the condition, there is no universally accepted method of treatment, therefore management should be personalized based also on the clinician’s experience and on the options available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and A.I.V..; methodology, L.M and M.D.; software, L.M.; validation, R.S. and B.G.; formal analysis, L.M, G.D. and M.F.P; investigation, G.D and A.I.V..; resources, F.A., P.I, B.G.; data curation, M.D. and B.G; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and V.A.I.; writing—review and editing, S.R, P.L., G.B and M.F.P.; visualization, M.D., A.I.V.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, B.G..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable”

Informed Consent Statement

the patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Yu, B. R. , Lee, G. E., Cho, D. H., Jeong, Y. J. & Lee, J. H. Genital tract cavernous hemangioma as a rare cause of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol Sci 60, 473–476 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Itinteang, T. , Withers, A. H. J., Davis, P. F. & Tan, S. T. Biology of Infantile Hemangioma. Front Surg 1, (2014). [CrossRef]

- George, A. , Mani, V. & Noufal, A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 18, S117 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bandera, A. I. , Sebaratnam, D. F., Wargon, O. & Wong, L. C. F. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol 85, 1379–1392 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. , Lang, J. H. & Zhou, H. M. Venous malformations of the female lower genital tract. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 145, 205–208 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Krowchuk, D. P. et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics 143, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Madhu, C. , Khaled, M. A. & Putran, J. Vulval haemangioma in an adolescent girl. J Obstet Gynaecol 31, 187 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Russel, I. M. B. , Vote, P. A., Weyerman, M. E. & Vos, A. Local treatment of hemangioma of the urogenital tract. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 10, 207–209 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. G. et al. Vaginal bleeding due to an infantile hemangioma in a 3-year-old girl. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 22, (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ralph, C. et al. Infantile/Capillary Hemangioma of the Uterine Corpus: A Rare Cause of Abnormal Genital Bleeding. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 35, 597–600 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, P. Dangle, Lopa K. Pandya IV & Casimir F. Firlit. Bilateral asymptomatic incidental vulvar/labial hemangioma: Kissing Hemangiomas. https://journaldatabase.info/articles/bilateral_asymptomatic_incidental.html (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ganti, A. K. et al. Unusual Cause of Pediatric Vaginal Bleeding: Infantile Capillary Hemangioma of the Cervix. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 32, 80–82 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Arredondo Montero, J. , Bronte Anaut, M., Bardají Pascual, C. & Montes, M. Vulvar tumor in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol 39, E3–E4 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Talon, I. et al. [Vaginal hemangioma revealed by bleeding in a girl: a case report]. Arch Pediatr 13, 361–363 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Nichols, P. E. , Michaud, J. E. & Wang, M. H. Infantile hemangioma of the clitoris presenting as a clitoral mass: A case report. Urol Case Rep 15, 44 (2017). [CrossRef]

- P E North et al. A unique microvascular phenotype shared by juvenile hemangiomas and human placenta. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11346333/ (2001).

- Solman, L. et al. Oral propranolol in the treatment of proliferating infantile haemangiomas: British Society for Paediatric Dermatology consensus guidelines. Br J Dermatol 179, 582–589 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hoeger, P. H. et al. Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: recommendations of a European expert group. Eur J Pediatr 174, 855–865 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Sebaratnam, D. F. , Rodríguez Bandera, A. l., Wong, L. C. F. & Wargon, O. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: Management. J Am Acad Dermatol 85, 1395–1404 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bayart, C. B. , Tamburro, J. E., Vidimos, A. T., Wang, L. & Golden, A. B. Atenolol Versus Propranolol for Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas During the Proliferative Phase: A Retrospective Noninferiority Study. Pediatr Dermatol 34, 413–421 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Laurens, C. , Abot, A., Delarue, A. & Knauf, C. Central Effects of Beta-Blockers May Be Due to Nitric Oxide and Hydrogen Peroxide Release Independently of Their Ability to Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. Front Neurosci 13, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H. et al. Comparison of Efficacy and Safety Between Propranolol and Steroid for Infantile Hemangioma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol 153, 529 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gnarra, M. , Solman, L., Harper, J. & Batul Syed, S. Propranolol and prednisolone combination for the treatment of segmental haemangioma in PHACES syndrome. Br J Dermatol 173, 242–246 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, S. , Sathe, N. A. & Surawicz, T. Laser treatment of infantile hemangioma: A systematic review. Lasers Surg Med 48, 221–233 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. et al. Efficacy and safety of adrenergic beta-antagonist combined with lasers in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 36, 1135–1147 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Püttgen, K. et al. Topical Timolol Maleate Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics 138, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Drolet, B. A. et al. Systemic timolol exposure following topical application to infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 82, 733–736 (2020). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).