1. Introduction

Recent crises, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the climate crisis, and growing food insecurity, have highlighted the vulnerabilities of global supply chains and, consequently, a profound need for food system transformation.

Over the last decades, the concept of Local Food Policy and agroecology have gained increasing relevance in the international scientific audience due to the emerging global challenges facing our planet (climate, biodiversity, hunger, inequalities). They are progressively more accepted as sets of knowledge and practices that can convert entire food systems by bringing together the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability and adopting a bottom-up approach based on the local knowledge and participation.

Agroecology recognizes the interrelationships between people, agriculture and nature and the empowerment of farmers [

1]. On the other side, Local Food Policies promote the systemic approach and the inclusion of food issues within all policy areas, including environment, health, and social inclusion [

2]. Finally, both paradigms attempt to challenge the cultural and structural power dynamics existing in the current food system by reinforcing the self-organization of food producers and consumers.

The goal of this article is to demonstrate the potential of the link between these two paradigms to transform food systems toward sustainability. In particular, the article proposes an agroecological assessment methodology applied to urban agriculture in the city-region food system of Rome (Italy). The research provides an adaptation of the Performance Assessment Tool in Agroecology (TAPE) developed by FAO in 2019. The survey was given to a sample of 20 farms adhering to “Alveare che dice Sì” - a short food supply chain organization in Rome.

The results of the application of this methodology aim to inform the degree of agroecological transition of the selected farms, with particular attention to the relationship between city and countryside. The findings are noted to be relevant to the formulation and evaluation of the Local Food Policy of the city of Rome, demonstrating that agroecological assessments might be essential to formulate evidence-based food policies and transform the food system.

This article is structured in three parts. The first part presents the theoretical framework (1) of the analysis, first presenting the paradigms of Local Food Policy and agroecology in separate sections, and then focusing on the synergies between these two practices. In this section, the research will also present the city-region food system of Rome, which is the case study. This is followed by a second part dedicated to the explanation of the methodology (2), that is the agroecological assessment adapted from the TAPE framework [

3]. In the third section, the results (3) deriving from the application of the methodology to the sample of farms will be presented. Finally, some discussions and conclusions will be outlined.

1.1. Theoretical framework

1.1.1. Local Food Policy

Local Food Policies (or Urban Food Policies) are defined as processes through which cities envision change in their food systems and in how they strive to achieve this change [

4] (p. 6). Specifically, Local Food Policies are characterized by a strong systemic and cross-sectoral approach, which considers the interconnections between the social, environmental and economic dimensions. In attempting to transform the food system, Food Policies aim to bring about changes in the various sectors, such as education, health, social services, public procurement, economic development, land use and agriculture.

Moreover, in the empirical contexts in which Food Policies were implemented, new governance dynamics occurred, such as participatory processes involving actors from civil society, public institutions, and private sector.

According to Sonnino [

5], Urban Food Policies in Europe and North America are distinguished by four key characteristics, representing a significant change from the past. First, they are characterized by a systemic vision, which means embedding food issues in all policy areas. Second, they promote a concept of "new localism", since they emphasize the territorial dimension and considers the “city-region food system”. Some scholars and practitioners [

6] identify in the city-region food system a new "geographic entity" denoting a target area which goes beyond the administrative boundaries of the city and includes ecological and social connections with the surrounding area. Third, they foster a type of participatory governance that promotes community capacity-building and new governance dynamics, for example through Food Councils [

7]. Finally, "trans-local" networks are emerging – such as the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP)-, capable of extending the relevance of Food Policy both geographically and politically.

Finally, we can say that Urban Food Policies aim to democratize and transform food systems by empowering citizens and facilitating their participation in food policy development and implementation.

1.1.2. Agroecology

Over the last 20 years, the concept of agroecology has gained increasing relevance in the international scientific audience. It is becoming a basis for converting entire agri-food systems by bringing together the several of sustainability [

8] and adopting a bottom-up approach based on the knowledge and natural resources of local communities for agricultural production (Nicholls and Altieri, 2018). Agroecology recognizes the interrelationships between people, agriculture and nature and the empowerment of farmers [

1], due to its multidimensional nature: as a science, as an innovative agricultural practice and as a grassroots socio-political movement of small-scale producers [

9].

Agroecology is rooted in practices, ecological farming projects, and phenomena of resistance to the spread of industrial agriculture by indigenous farmers in Latin America [

10,

11,

12]. In 1928, Bensin [

13] used this expression to refer to the application of the principles and concepts of ecology to agriculture. Starting in the 1970s, in response to the homologation dictated by the Green Revolution, agroecology began to take on connotations of an ideological nature, advocating an ecological view of agriculture through the inclusion of the concept of agroecosystem, understood as a harmonious combination of natural and artificial ecosystems. In the 1980s, attention was focused on the concept of “sustainability” related to the agricultural sector, as a model capable of protecting natural resources [

14].

In the 1990s, agroecology began to take on a social character in connection with critical reflection on food consumption patterns [

15], focusing on the interrelationships between production, distribution, and consumption. In 2007, Gliessman redefined agroecology as a science that applies ecological concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agri-food systems [

16]. Several sets of agroecological principles have been produced in the scientific literature [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], the most recent including those formulated by CIDSE [

23], FAO [

24] and INKOTA [

25].

The implementation of these principles is useful not only to reduce the use of non-renewable resources [

26], but also to activate endogenous development dynamics. In this context, agroecology proposes the foundations for defining new areas such as the foodshed and alternative food networks [

27,

28], both of which address the sustainability of food systems. In 2018, the FAO, recognised agroecology as a significant approach to achieving the sustainability goals of agricultural and food systems, intercepting the 10 elements as a guide for policymakers, farmers and other stakeholders involved in planning, managing and monitoring the agroecological transition [

24].

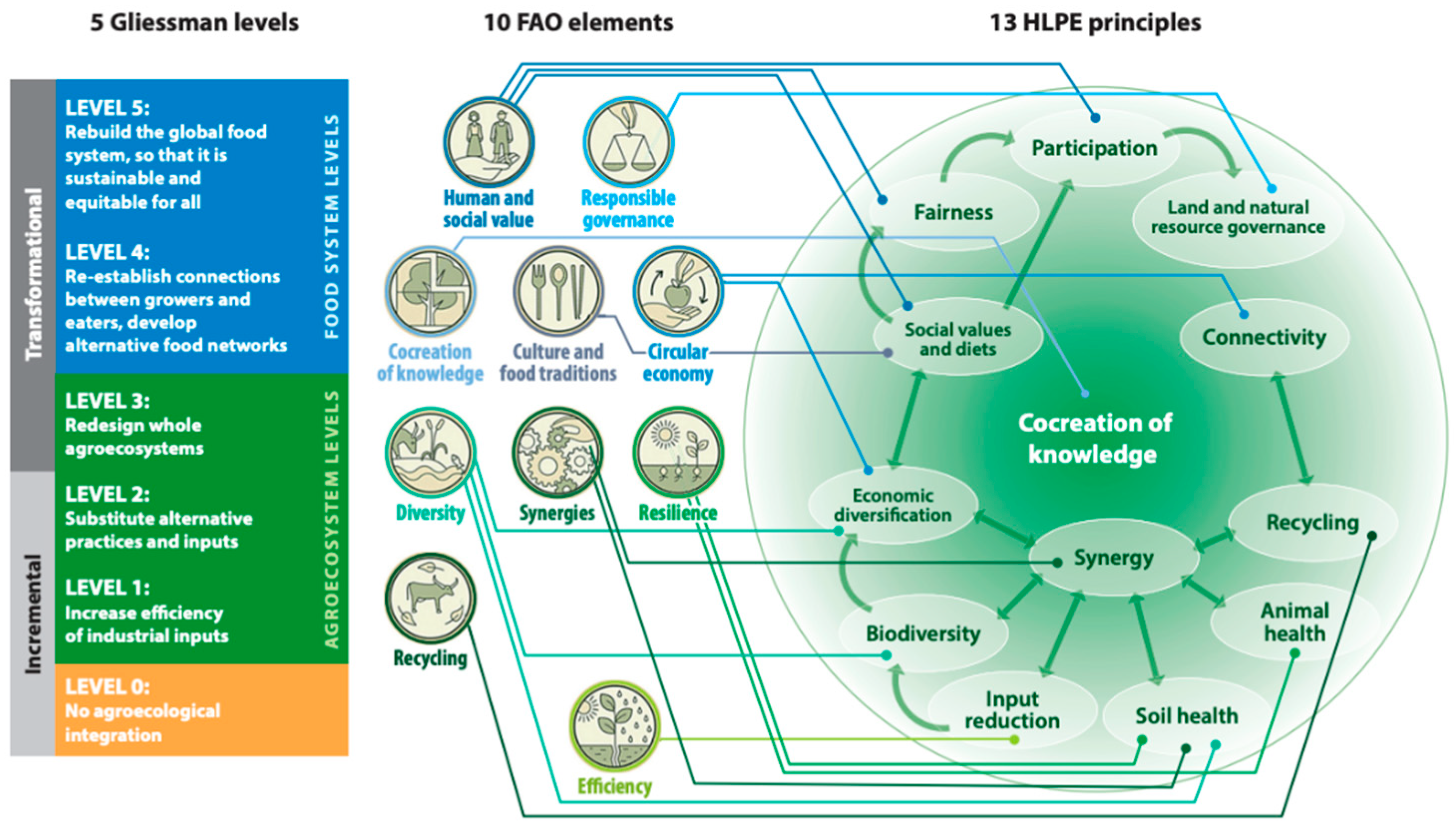

In 2019, a high-level expert group defined the 13 principles of agroecology (HLPE, 2019) needed to operationalize the agroecological approach in the Performance Assessment Tool in Agroecology (TAPE) methodology including: reuse of waste; reduction of input use; soil health, animal health and welfare; biodiversity; synergy; economic diversification; knowledge co-creation (interaction between local knowledge and global science); social values and dietary regimes; fairness; connectedness; land and natural resource management; and participation (

Figure 1).

1.1.3. Synergies between Food Policy and Agroecology

According to Gliessman [

16], the agroecological transformation of the agri-food system passes through a process consisting of five steps:

increasing input use efficiency;

replacing conventional inputs and practices with agroecological alternatives;

redesign the agroecosystem on the basis of a new set of ecological processes;

restoring a more direct connection between producers and consumers;

building a new global food system based on participation, locality, equity and justice, where only the last three steps are recognized as having real transformative capacity.

Considering these steps, agroecology offers a new multidisciplinary approach to transform food systems at territorial level, considering the interconnections between dimensions (i.e. social and economic) and sectors (i.e. production and consume). According to the agroecological approach, urban contexts and urban-rural relations assume a central role and become places of interest for all activists and researchers engaged in issues pertaining to agrarian issues and agroecological transitions [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Therein lies the convergence between food policy and agroecology: both aim at an inclusive and sustainable transformation of the food system, reconsidering the interconnection between social, environmental and economic dimensions (See

Table 1). Not only that, but they also take into account a territorial approach, based on local knowledge and participation, countering asymmetric power dynamics in the food system. However, while the former provides suitable governance tools to support the transition (i.e. Food Policy Councils, participatory decision-making processes), the latter offers ecological principles to make food production and consumption more sustainable.

In empirical contexts, experiences in the field of urban agroecology [

34] and farmers' participation in Local Food Policies for food system have converged and marked the rise of a new research agenda aimed at linking food sovereignty and urban movements.

Specifically, urban agroecology, understood as the expansion of urban agriculture, promises to overcome the unsustainable link between rural and urban-periurban activities [

35]. This activity is considered central to both agroecology practices and Food Policy implementation.

Thus, considering the convergence of these two practices in transform the city-region food system, this article aims to demonstrate how one can be functional to the other, particularly in the assessment and formulation of evidence-based policies.

1.1.4. The city-region food system of Rome

Through a series of fragmented processes, the city of Rome has always been characterized by strong links between the urban population and local agriculture, until recent decades, when long industrialized food chains have become increasingly dominant [

37], breaking down that traditional link between city and countryside. The weak commitment of the public sector, however, failed to stop the strong will of informal groups and organizations engaged in the attempt to create collective democratic dynamics for the transformation of the local food system [

38]. There is a lot of excitement in the Roman context with rapidly growing initiatives aimed not only at supporting conscious actions in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but also aimed at building coordination between the different actors in the urban food system. In fact, the bottom-up process of the city's Food Policy, which involves a wide range of actors willing to build more resilient and sustainable development models, is being carried out. The proposal for a Food Policy for Rome stems from the desire of the promoting committee to bring together people and realities active in different spheres.

In 2019, the Terra! Association and Lands Onlus launched 'A Food Policy for Rome' [

39], an analysis and mapping of the Roman food system that aimed to highlight its criticalities and prospects, presenting the institutions with 10 operational principles to initiate a food policy aimed at sustainability, the protection of local producers and the right to food. This event marked the beginning of a formal dialogue between the municipality and the group that culminated in the unanimous approval of the Capitoline Assembly in 2021 of Resolution 38/2021 laying the foundations for a food policy. Resolution 38 consists of the same principles outlined in the proposal and includes a commitment by the municipality to:

the formulation of a strategic document of the Food Plan with vision, principles and guidelines (Art. 2);

the establishment of the Food Council (Art. 3);

the establishment of a technical office for the implementation of the Rome Food Policy (Art. 4).

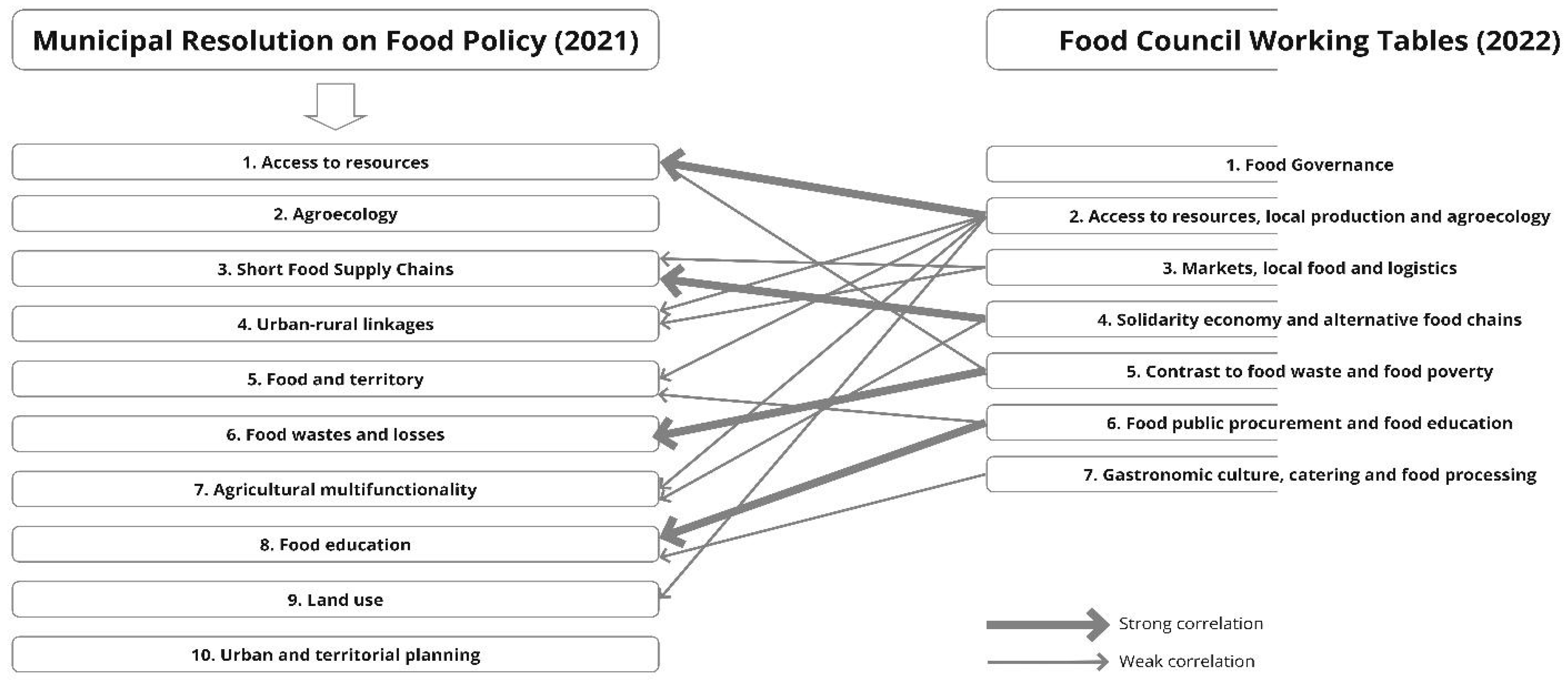

On 23 February 2022, the provisional Food Council took office, chaired by the President of the Environment Commission of the City Council, which initiated the creation of 7 working tables related to the 10 operational objectives (

Figure 2) of the proposal document well depicted by Marino and Mazzocchi [

39] in the article 'The Evolution of Food Policy in Rome: Which Scenarios?’.

As we can see from

Figure 2, the

Table 2 'Access to resources, local production and agroecology' is of considerable weight since it is simultaneously connected to several Food Policy objectives. Therefore, Food Policy aims to use the agroecological approach to support innovation in local food systems through the involvement of different actors.

Turning our attention to the agricultural side, on the other hand, the municipality of Rome, the largest agricultural municipality in Italy, has a millenary agricultural and food history with 45% of the area consisting of agricultural land. The relationship between the city and its Agro, Roman productions, markets, operators, companies, and gastronomic traditions represent identity elements of the city [

41].

The strong pressure of urbanization between 1990 and 2000 caused a 42% reduction in the utilised agricultural area (UAA); this trend was reversed between 2000 and 2010, with an increase in UAA of 14% [

40] and a further increase of 5.72% between 2010 and 2020. To date, a very important aspect that characterizes agriculture in our country and which is also reflected at the regional and municipal level is represented by a dichotomy regarding the size of farms and the UAA [

42,

43], i.e. fewer but larger farms. The latest agricultural census [

44] draws attention to the ongoing process of concentration of agricultural entrepreneurship.

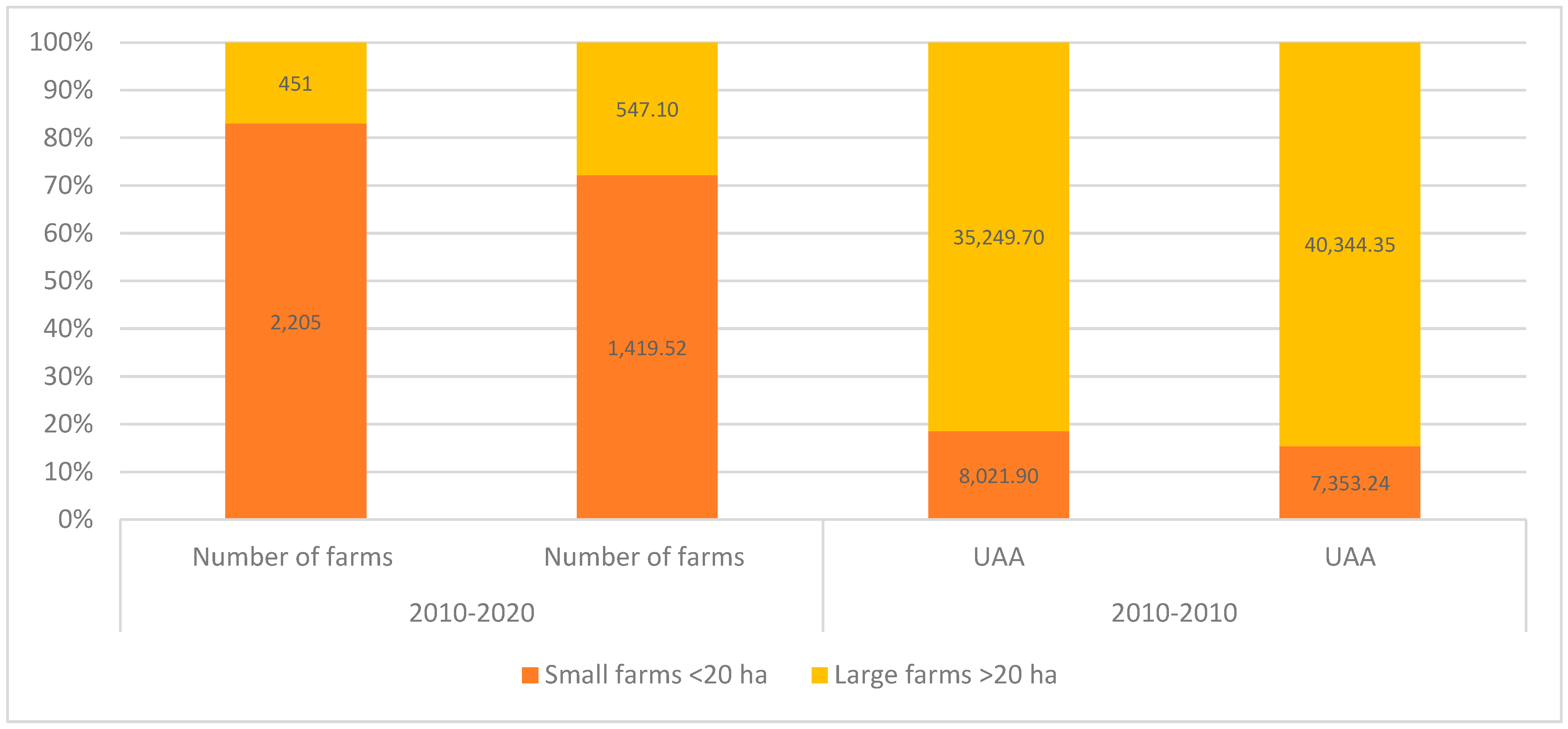

The report confirms that the average size of farms has doubled over the period 1982-2020 in terms of UAA (from 5.1 to 11.1 average hectares per farm) and SAT (from 7.1 to 14.5 average hectares per farm). Shifting our gaze to the territorial boundaries of the Municipality of Rome, through an elaboration of regional data from 2020 and 2010 and municipal data from 2010 (

Figure 2), it was possible to calculate an estimate of the municipal data in 2020 of the number of farms and UAA by UAA classes (from 0 to 19.99 hectares and from 20 to over 100 hectares).

The estimated data tell us that there are 1,966.62 farms in 2020 with a decrease of 25.96% compared to 2010. Similarly, the UAA of small farms in 2020 is 7,353.24 with a percentage change of -8.34 compared to 2010, while the UAA of large farms is 40,344.35 with a positive percentage change of 10.23. In relation to the distribution of holdings by classes of utilized agricultural area, holdings between 0 and 19.99 hectares occupy 15.42% of the UAA compared to 84.58% of large holdings (> 20 and over 100 hectares). This shows that there is a strong prevalence of large farms (

Figure 3), which are smaller in number but hold a high percentage of the UAA.

Similarly, according to the latest ISPRA report [

45], Rome is the city that consumes more soil on average than other cities, over 90 hectares, since 2006. In 2021, the city lost 95 hectares of previously natural or semi-natural soil and more than half of the soil consumption can be traced back to a form of transition classified as building site areas. In the same year, Rome also consumed soil for new built-up areas and for the expansion of quarry areas and paved areas for car parks or yards.

The observation of soil consumption is necessary because it is a phenomenon that generates negative effects on climate change such as the loss of ecosystem functions, the increase of extreme phenomena and the modification of albedo and consequent positive forcing (heat islands). In a scenario like the one in Rome where there is a lot of land consumption and land is increasingly concentrated in a few hands, the agro-ecological transition of urban and peri-urban agriculture acquires full relevance with respect to the implementation of food policy.

In essence, as part of a transformative process of the urban food system, the agroecological approach would lead to the reorganization of the material flows, social and economic relations of the city-region food system context. In this sense, in this paper we found it interesting to understand and analyze a sample of companies representative of the Roman territory in order to verify the existence or absence of complementarities between the agroecological model and food policy. Furthermore, the data show us that the implementation of agro-ecological principles by companies is certainly essential, but in order to increase the significant impact on the entire ecosystem, a greater involvement of large companies that hold more UAA would be inevitable.

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate agroecological transition at the farm level, the FAO has developed the TAPE framework, launched in 2019 [

3]. The TAPE (Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation) model as a performance evaluation method in agroecology is based on several existing evaluation frameworks. TAPE is a comprehensive tool that aims to measure the multidimensional performance of agroecological systems across different dimensions of sustainability, in different contexts and at different scales, with the aim of supporting specific policy development in this regard. It uses a household and farm scale approach, but also captures information and provides results at the territorial level [

3].

TAPE is based on the analytical framework called MESMIS (The Evaluation of Natural Resource Management Systems) [

46], a reference evaluation framework generally used in Latin America, which provides principles and guidelines for the quantification and integration of context-specific indicators through a multi-stakeholder participatory process. In our work, TAPE is the basic methodological tool from which we started to carry out the agroecological analysis on the Roman territory.

Considering that the TAPE model was created to measure the multi-dimensional performance of developing countries’ agroecological systems across the different dimensions of sustainability, this work envisaged a re-adaptation of it to the western context and more specifically to the territorial food system of the city of Rome. The research considered a sample of 20 farms belonging to the “Alveare che dice sì!” (from here on “hives”, as “alveare” translates in “hive”).

It is a short food supply chain experience, comparable to a Solidarity Purchasing Group, in which there are no intermediary relationships. Producers and consumers meet in presence for the selling, thus favoring direct relationships. The choice of farms was made considering that they belong to an innovative type of short food supply chain in which environmental, relational, social, and economic objectives should be fully integrated. Our hypothesis is that these farms’ features contain elements from which valid principles can be extracted to guide the agroecological transition of the Roman agro-food system.

The questionnaire was administered in the period September-October 2022, to farms and processing companies in the Lazio area that fall within one of three hives: “Marconi Roma”, “Roma Monteverde”, and “Roma bio appetito Spinaceto”. The structure of the questionnaire was organized in 3 sections: a farm descriptive section, an agroecological section; a section on the importance of participation in the hive. In the second section, eleven questions were asked, corresponding to the ten agroecological principles of TAPE [

3] and covering the four areas identified by Sahlin et al [

47] (see

Table 2).

Each question contains five response modes, constructed on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. By combining the eleven questions, a composite indicator was created expressing the agro-ecological gradient of the farm, which can range from 10 to 50 or from 0 to 100 when expressed as a percentage. Based on the data obtained from the administration of the questionnaire to the farms that are part of the “Alveare che dice sì!”, it was possible to investigate:

whether the agro-ecological model is found in farm management activities, i.e., in peri-urban agriculture;

whether participation in the “hives” has induced changes in an agro-ecological sense;

analysing the agro-ecological characteristics of farms in the Roman context, to extract principles that can inspire and guide the directions of the food policy process.

3. Results

3.1. Farms structure

A total of 19 farms completed the questionnaire. Of these, 11 are sole proprietorships, i.e. consisting of a single working partner, 6 are simple agricultural companies and only one is a corporation. The average farm size expressed in TFA (Total Farm Area) is 31.4 hectares. Of these, 78.3% are Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA). It should be noted that, among the farms considered, one has a TFA of 250 hectares, without which the average would be 19.2 hectares.

As for the distribution of UAA, the first quartile is found at 2.65 hectares, the second quartile at 7.5 hectares, and the third quartile at 25.5 hectares, thus highlighting the fact that the sample is characterized by the presence of half of the farms with a size close to the Italian average (8.4 hectares). It is observed a concentration of farms in the smaller size classes: 40% have a UAA between 0 and 5 hectares, and the 30% between 5 and 20 hectares. The larger farms (more than 20 hectares) concentrate almost 85% of the productive areas.

The distribution of holdings by type of land ownership is characterized by private ownership in about half of the cases, while the other half is evenly distributed between mixed ownership-rental and rent-only modes. Apart from a causal link between type of ownership and farm size, which would have to be demonstrated, the UAA ranges from 11.7 hectares for rental, 26.9 for mixed modes and 33.4 in the case of land ownership. In 60% of cases, the farms have a production orientation based on vegetable crops (mixed herbaceous and/or arboreal), and mainly market fresh products, but also processed products such as oil and products in oil, jams, fruit juices, bakery products, and wine.

The 20% are specialized in animal production with the production and marketing of dairy products and processed meat (mainly pork and beef). The remaining 20% of the farms have a mixed orientation with cultivation and breeding, and mainly market fresh products of vegetable and animal origin, processed meat, cheese and oil. Only 20% of the sampled farms produce PDO-PGI products. The 60% of the farms have adopted 'non-conventional' production models (organic or biodynamic) while the remaining 40% adopt conventional farming model. However, it should be noted that in the first group, non-certified forms or Participatory Guarantee Systems prevail; in average, these farms have an extension of less than 20 hectares. Smaller farms, having few financial resources to pay for certification, and relying on trust (typical of direct sales), prefer to not have an organic certification [

48]. In terms of work units, the average is 3.8, of which about two thirds are family members.

Thus, the farms in the sample are characterized by a marked prevalence of family farming: in fact, about half of them employ only family workers, while in cases where salaried labor is present, this exceeds family labor in percentage terms on one farm. In all other cases where wage labor is employed, this amounts to about 41% of the total labor units. The degree of multifunctionality, despite the farms fall fully under peri-urban agriculture [

49], is modest: only the 26% has a complementary activity to primary production, mainly focused on agritourism as supplementary source of revenue and internal re-utilization of farm products.

3.2. Agroecological gradients

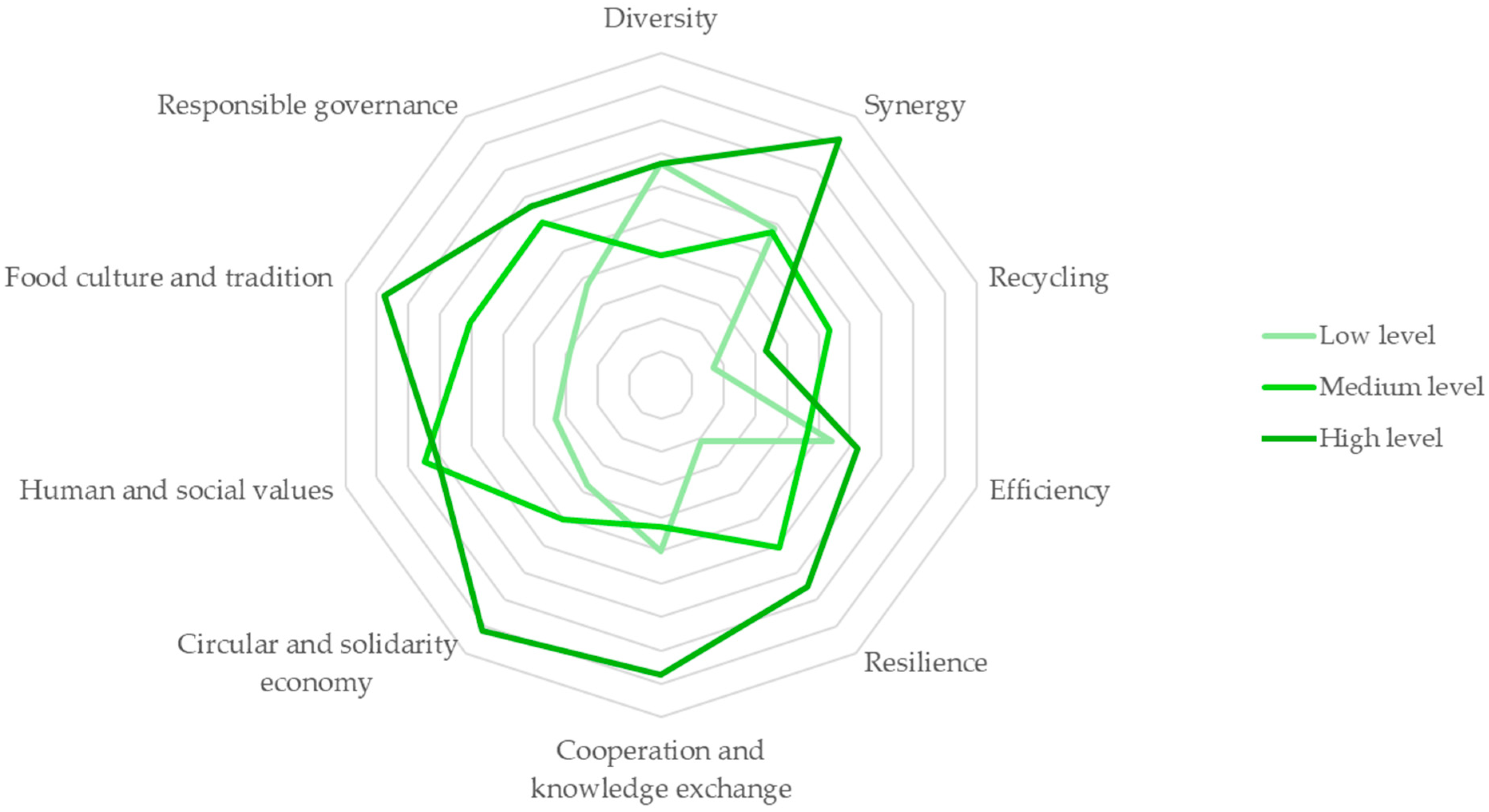

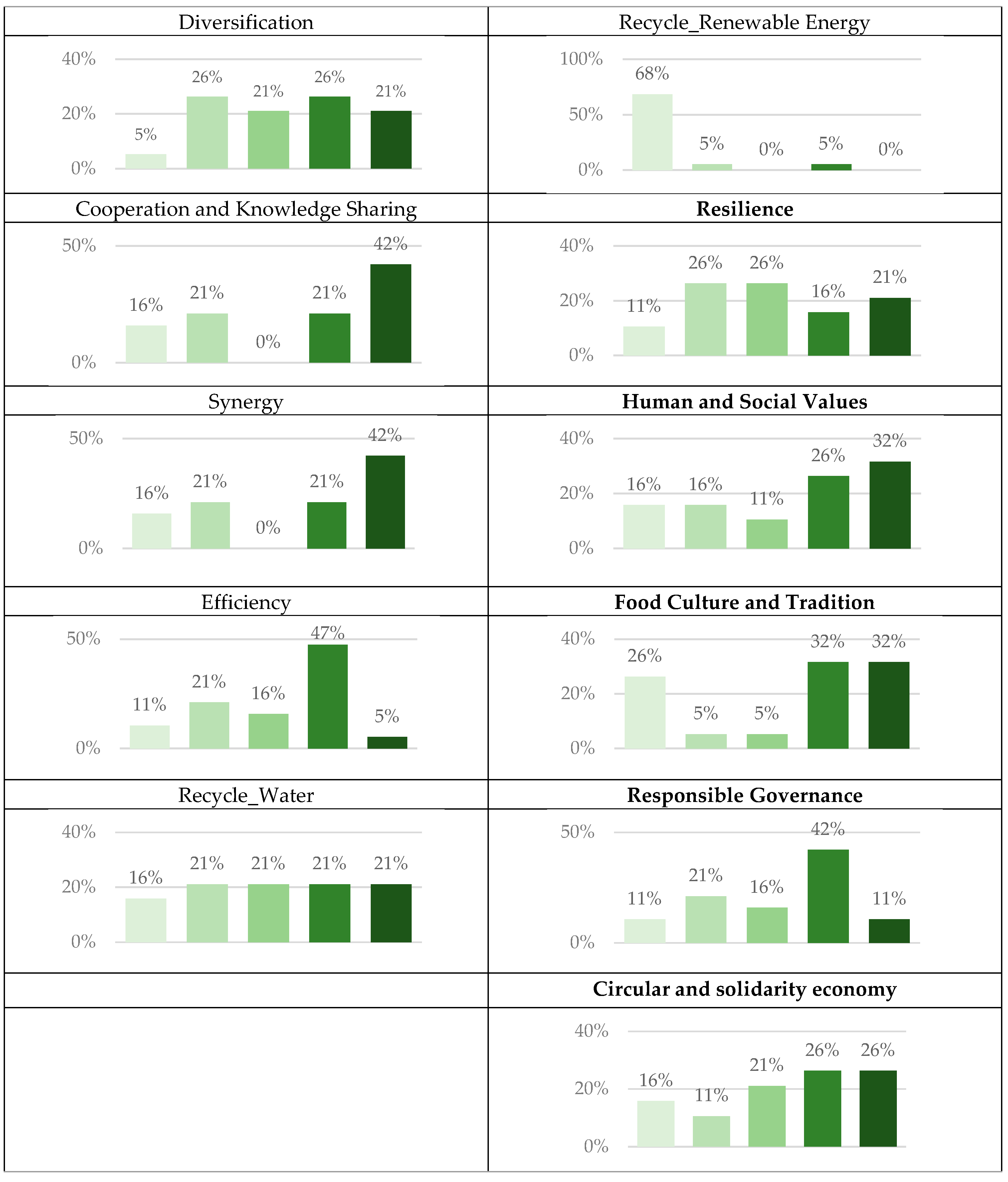

Table 3 gives the results of the questionnaire with respect to the ten agro-ecological dimensions consistent with the TAPE theoretical reference model. Summing up, for each question, the frequencies of the answers with the highest agroecological gradient (medium-high and high), it emerges that the principles of Synergy and Food Culture and Tradition are the ones most pursued by the farms surveyed (63% in both cases). Next come Human and Social Values (58%), Cooperation and Knowledge Sharing, Efficiency, Responsible Governance and Circular and Solidarity Economy (53%). The lowest values, obtained by summing the frequencies of the two response modes with the lowest agro-ecological gradient (medium-low and low), are consistently achieved by the principle of Renewables (74%, only one company has significant renewable energy production). Not very positive results also for the Recycling and Resilience principle (both 37%).

On the basis of the response patterns recorded by each farm with respect to the ten agro-ecological principles, it has been possible to obtain a synthetic indicator that assigns a score on a gradient from 0 to 100. Subsequently, the farms were ranked on three levels (low, medium and high), through a subdivision into tertiles. The results show a distribution of tertiles with the first level from 28.8% to 48.7%, the second from 48.8 to 60.0% and the third from 60.1 to 100 (see

Table 4).

Following the subdivision of the farms by low, medium and high agro-ecological level, the average level for each agro-ecological principle of the farms belonging to the same level was calculated (see

Figure 4).

3.3. Farm strategies

An element little explored in the international literature is whether the path towards agroecological principles leads to changes in business strategy. Or, in other words, whether agroecology can represent a business strategy of adaptation to new market conditions and new consumer needs, especially in urban areas. To this end, an indicator was first developed to summarize the motivations that led the companies to join the food short supply chain of the “Alveare che dice sì”. The questionnaire was structured to distinguish between social and more strictly economic motivations.

In particular, the following reasons were considered strictly economic: guaranteeing fair remuneration; improve market access. The motivations of a social nature are: social commitment towards communities; desire to promote greater access to quality products; desire to make consumers aware of their products and their approach. Considering the entire sample, the motivations that pushed the farms to join the short supply chain system under study are more of a social nature (desire to make the consumer aware of their products and their approach; desire to encourage greater access to quality products).

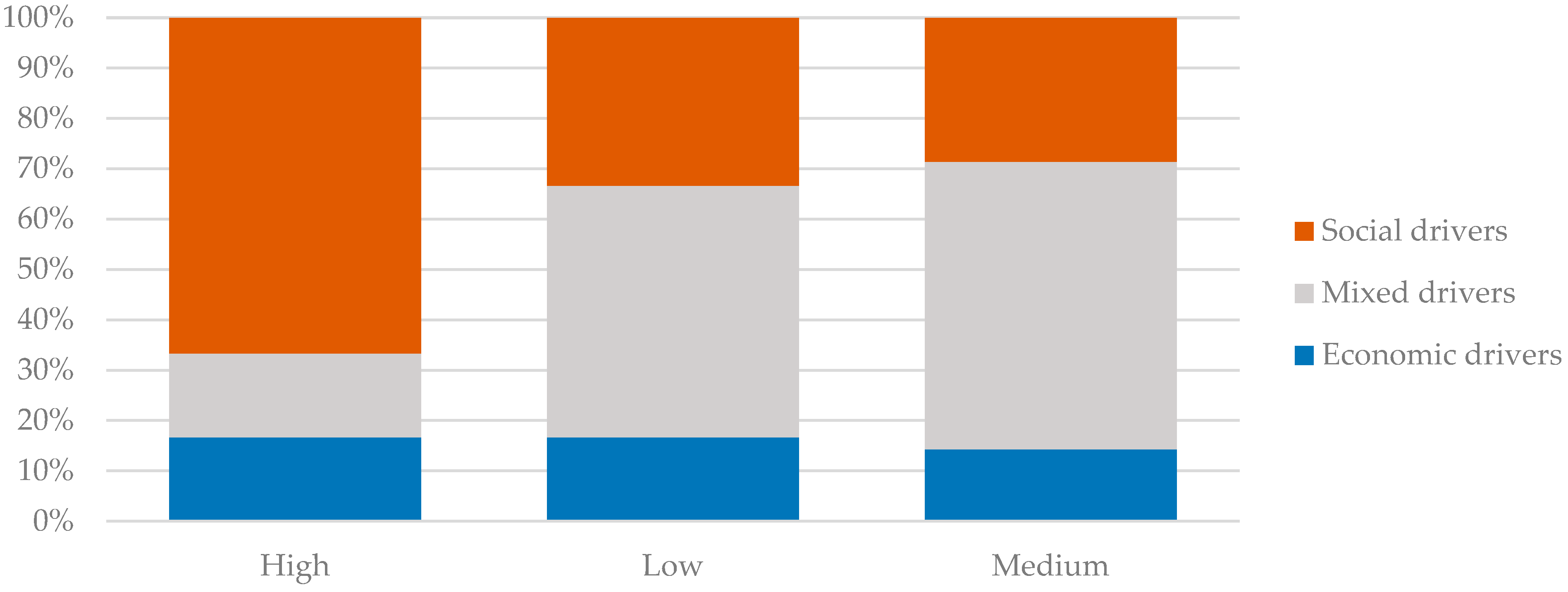

The least prevalent motivation is that relating to the search for fair remuneration. Based on the prevalence of economic or social motivations, or a balance between the two, farms have been classified into "Economic drivers", "Social drivers" and "Mixed drivers".

Figure 5 shows that higher agroecological level are correlated with a prevalence of social drivers, while low and medium agroecological levels are more balanced and characterized by a mix of motivations both economic and social.

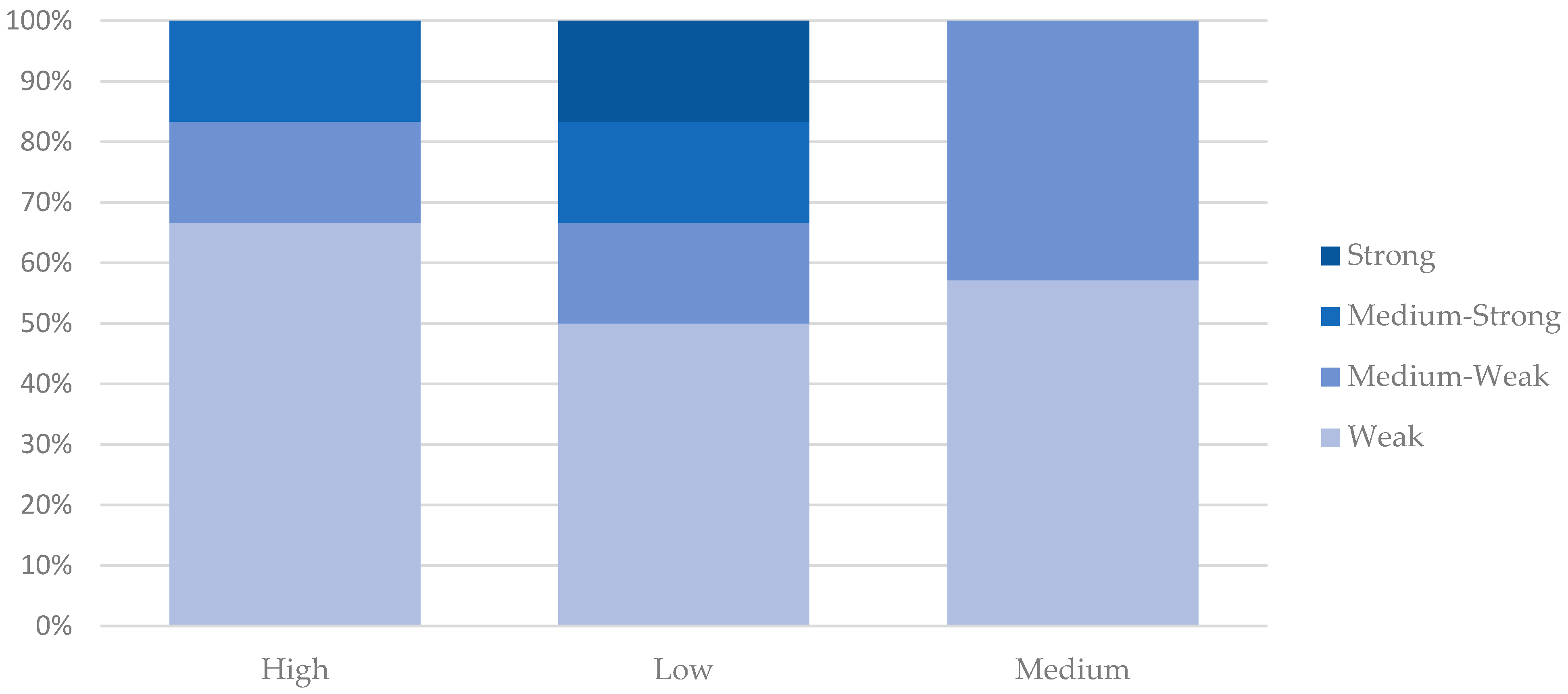

Another important aspect in order to explore the farms’ strategies in relation to joining the “Alveare che dice sì” is the degree of innovation. For all surveyed farms, joining the new sales channel has generated changes in business management and planning models. The most widespread innovation is corporate investments to access the short supply chain, packaging and digital innovation. Much less widespread have been the development of new production processes and, in no case, systems to guarantee better working conditions for the workforce employed. However, also in this case it was possible to build a synthetic indicator based on the innovations made with respect to a potential list, in order to compare it with the agroecological level. Based on the responses received, four innovation levels were created: Weak (only 1 innovation introduced), Medium-Weak (2 innovations introduced), Medium-Strong (3 innovations introduced), Strong (4 innovations introduced). 11 farms have a Weak innovation level, 5 have a Medium-Weak level, 2 have a Medium-High level, and only one has a High level.

Figure 6 highlights that there is no direct correlation between a high agroecological level and the innovation gradient introduced into the farm. On the contrary, it is found that the only farm with a innovation gradient classified as Strong, falls into the low agroecological level classification.

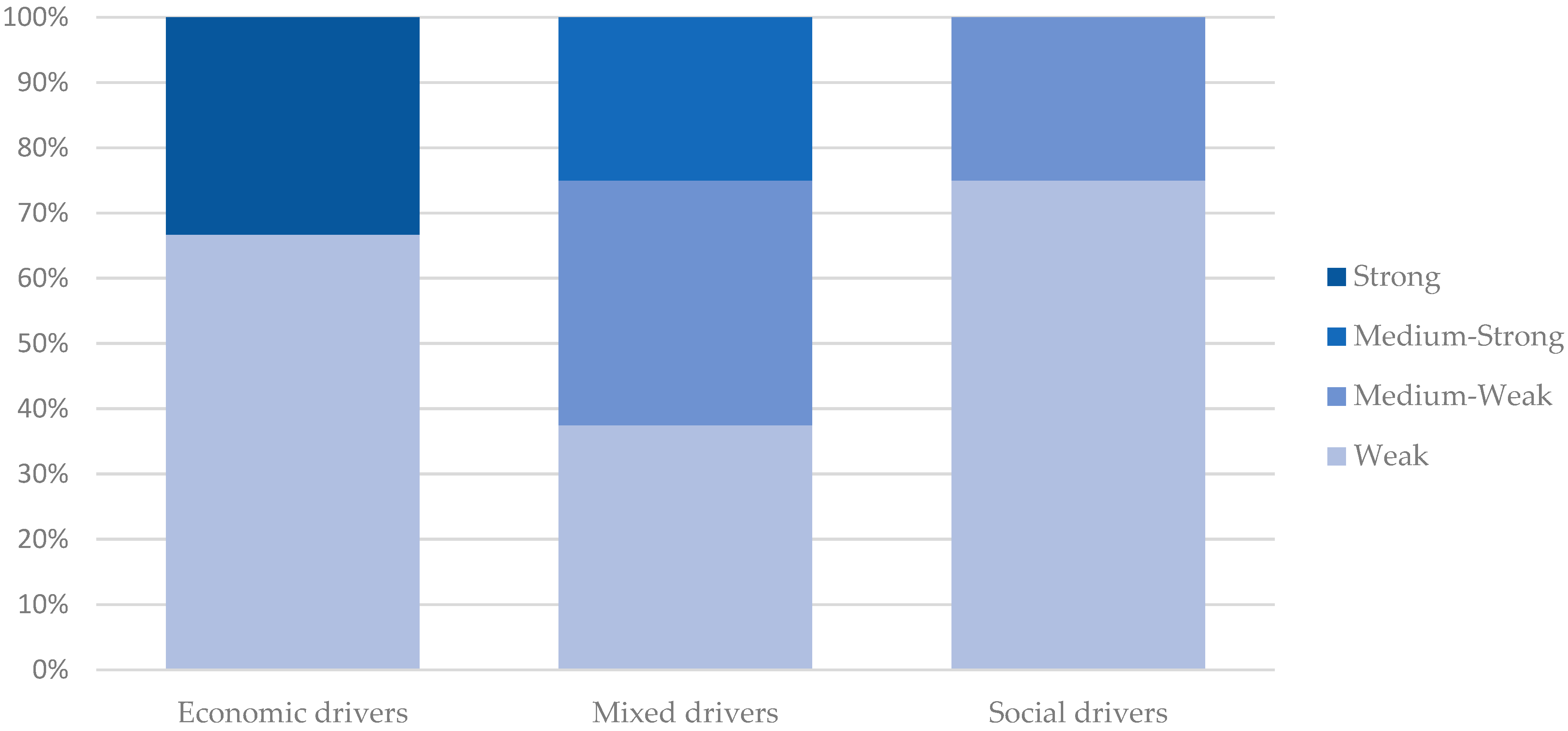

Finally, the degree of innovation and the drivers have been correlated (See

Figure 7). Also, in this case an inverse relationship is highlighted between propensity for innovation and social motivations, while increasing the economic-mercantile component also increases - albeit in the context of a generally low propensity for innovation - the degree of innovation.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The objective of this research work was to evaluate the potential relationship between local food policies and agroecology through the application of an agroecological assessment methodology.

Specifically, Gliessman's 5 levels start from transformations in agricultural production to a broad food system transition, going in the same direction as local food policies.

Throughout the article, the agroecological level of a panel of peri-urban farms around the city of Rome was measured. The research aimed to investigate in what type of farms agroecological principles are most widespread and how agroecology matches up with their business strategy.

The choice of a panel of farms working on proximity relationships (urban - rural linkages) is even more important because these relationships (which have always existed) today are articulated in innovative and transformative ways and because they are at the core of local food policies. The tool employed provides evidences for local food policy formulation and evaluation, in the light of the fully integrated multiscale systems approach from farm to region to globe that is necessary to enhance agroecology [

29].

Regarding the agroecological gradient of the farms, it appears that farms are evenly distributed across the three levels (High, Low and Medium). Also, some agroecological principles are pursued more than others (as, for example, Cooperation and Knowledge Sharing, and Sinergy). About the drivers (Social, Economic or Mixed) of the farms to be part of the "Alveare che dice Sì" short food supply chain, the results show that higher agroecological levels are correlated with a prevalence of social drivers, while low and medium agroecological levels are more balanced and characterized by a mix of both economic and social drivers.

Regarding the innovations (from Weak to Strong) adopted by the farms to be part of the short food supply chain, there is no direct correlation between a high agroecological level, and the gradient of innovation introduced on the farm. On the contrary, it is found that the only farm with an innovation gradient classified as strong falls into the low agroecological level classification. About the connection between innovation and drivers, we observe an inverse relationship between propensity to innovate and social motivations, while increasing the economic-mercantile component also increases the degree of innovation - albeit in the context of a general low propensity to innovate.

In a nutshell, farms with the highest agroecological level, have a less "economistic" approach and are mainly driven by social factors. These farms have a lower propensity to innovate than those motivated by economic drivers and low agroecological level. We observe a kind of polarization between economic and social motivations of farms, with the former being more innovative and the latter characterized by a higher agroecological level. Returning to theoretical assumptions, this agroecological analysis can inform the Rome Food Policy on urban agriculture farms to shed light on their motivations and degree of innovation.

Also considering these data against the context of urban and peri-urban agriculture in Rome, we observe that there is a negative variation in the number of small farms and most of the arable land belongs to large farms. From a Food Policy point of view, it may be necessary to introduce tools to promote agroecology towards small farms, because not all of them (as the research shows) have a sufficient agroecological level, but also towards large farms since they are more prone to innovation and represent most of the urban and peri-urban agriculture. In conclusion, the research emphasizes the importance that agroecological transition should be promoted through a local food policy at all levels and should not only go through drivers related to social factors but is supposed to be integrated into the business strategies of farms of any size.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; methodology, D.M.; data curation, G.M., and F.B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C and F.B.F; writing—review and editing, F.C.; supervision, G.M. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

this research did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are especially grateful for the cooperation provided by the ‘Alveare che dice Sì’.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, C. R., Maughan, C., & Pimbert, M. P. Transformative agroecology learning in Europe: Building consciousness, skills and collective capacity for food sovereignty. Agriculture and Human Values, 2018, 36: 531–547.

- Hawkes, C., & Parsons, K. Brief 1: Tackling food systems challenges: the role of food policy. 2019.

- FAO. TAPE Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation 2019 – Process of development and guidelines for application. Test version, 2019, Rome.

- Moragues, A., Morgan, K., Moschitz, H., Neimane, I., Nilsson, H., Pinto, M., Rohracher, H., Ruiz, R., Thuswald, M., Tisenkopfs, T., and Halliday, J. Urban Food Strategies: the rough guide to sustainable food systems, Document developed in the framework of the FP7 project FOODLINKS, 2013.

- Sonnino, R. Urban food geographies in the global North. A RENEWED READING OF THE FOOD-CITY RELATIONSHIP, 2017, 39.

- Blay-Palmer, A., Santini, G., Dubbeling, M., Renting, H., Taguchi, M., & Giordano, T. Validating the city region food system approach: Enacting inclusive, transformational city region food systems. Sustainability, 2018, 10.5: 1680.

- Gupta, C., Campbell, D., Munden-Dixon, K., Sowerwine, J., Capps, S., Feenstra, G., & Kim, J. V. S. Food policy councils and local governments: Creating effective collaboration for food systems change. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 2018, 8.B: 11-28.

- Gliessman, S.R. Transforming food and agriculture systems with agroecology. Agriculture and human values, 2020, 37.3: 547-548.

- Toledo, V. M. La agroecología en Latinoamérica: tres revoluciones, una misma transformación. Agroecología, 2011, 6: 37-46.

- Guzmán, E. S. La participación en la construcción histórica latinoamericana de la agroecología y sus niveles de territorialidad. Política Y Sociedad, Madrid, 2015, 52 (2): 351–370.

- Altieri, M.A., and Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in Latin America: rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. Journal of peasant studies, 2011, 38.3: 587-612.

- Holt-Giménez, E. Campesino a campesino: voices from Latin America's farmer to farmer movement for sustainable agriculture. Food first books, 2006.

- BENSIN, B. M. Agroecological characteristics description and classification of the local corn varieties. 1928.

- Belliggiano, A.; & Conti, M. L'agroecologia come formula di sostenibilità e recupero dei saperi locali. Perspectives on rural development, 2019, 2019.3: 375-400.

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development, 2009, 29.4: 503-515.

- Gliessman, S.R. Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems, 2007, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

- Reijntjes, C.; Haverkort, B.; Waters-Bayer, A. Farming for the future: an introduction to low-external imput and sustainible agriculture. Leusden, NL: Ileia, 1992, 1992.

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: the science of sustainable agriculture. Westview Press, 1995, Boulder, USA.

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology and the Search for a Truly Sustainable Agriculture. Mexico: United Nations Environment Programme. 2005.

- Stassart, P.M.; Baret, P.V.; Grégoire, J.C.; Hance, T.; Mormont, M., Reheul, D.; Stilmant, D.; Vanloqueren, G.; Vissser, M. L’agroécologie: trajectoire et potentiel. Pour une transition vers des systèmes alimentaires durables. In: Agroécologie. Éducagri éditions, 2012. p. 25-51.

- Dumont, B.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Jouven, M.; Thomas, M.; Tichit, M. Prospects from agroecology and industrial ecology for animal production in the 21st century. animal, 2013, 7(6), 1028-1043.

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A.; Vazquez, L. Agroecology: principles for the conversion and redesign of farming systems. J Ecosys Ecograph S, 2016, 5: 010.

- CIDSE. The principles of agroecology. towards just, resilient and sustainable food systems. 2018. https://www.cidse.org/publications/just-food/food-and-climate/the-principles-of-agroecology.html.

- FAO. Los 10 elementos de la agroecología guía para la transición hacia sistemas alimentarios y agrícolas sostenibles. 2018. http://www.fao.org/3/i90 37es/I9037ES.pdf.

- INKOTA. Strengthening agroecology. For a fundamental transformation of agri-food systems. Position paper directed at the German Federal Government. 2019. https://webshop.inkota.de/node/1565.

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: concepts, principles and evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2008, 363.1491: 447-465. London.

- PAÜL, V., MCKENZIE F.H. Peri-urban farmland conservation and development of alternative food networks: Insights from a case-study area in metropolitan Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). Land use policy, 2013, 30.1: 94-105.

- RENTING, H., MARSDEN, T.K., BANKS, J. Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and planning A, 2003, 35.3: 393-411.

- Ewert F., Baatz R., Finger R. Agroecology for a Sustainable Agriculture and Food System: From Local Solutions to Large-Scale Adoption. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2023. 15:351–81. [CrossRef]

- Tornaghi, C. Urban agriculture in the food-disabling city:(Re) defining urban food justice, reimagining a politics of empowerment. Antipode, 2017, 49.3: 781-801.

- Vaarst, M., Escudero, A. G., Chappell, M. J., Brinkley, C., Nijbroek, R., Arraes, N. A.,... & Halberg, N. Exploring the concept of agroecological food systems in a city-region context. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 2018, 42.6: 686-711.

- Dyck, B. V., Maughan, N., Vankeerberghen, A., & Visser, M. Why we need urban agroecology. Urban agriculture magazine, 2017, 33: 5-6.

- Weissman, E. Brooklyn's agrarian questions. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 2015, 30.1: 92-102.

- AA.VV. 2017. Urban agroecology. A thematic issue of the Urban Agriculture Magazine, No. 33. https://www.ruaf.org/ua-magazine-no-33-urban-agroecology.

- Juncos, M. A. Assessing Agroecological Principles at the Intervale in Burlington, Vermont: A Case Study and Multimethod Research with a Participatory Approach in a Peri-Urban Socioecological System. 2021.

- Marino, D.; & Viganò, L. Agroecologia e politiche del cibo: connessioni e sinergie nella ricerca di un processo di trasformativo dei food system. In: Agroecologia circolare. Dal campo alla tavola. Coltivare Biodiversità e innovazione. ReteAmbiente srl, 2021. p. 85-91.

- Cavallo, A.; Di Donato, B.; Marino, D. Mapping and assessing urban agriculture in Rome. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 2016, 8: 774-783.

- Ledant, C. Urban Agroecology in Rome. Urban Agriculture Magazine, 2017, 33. November.

- Lands Onlus, Terra Onlus, Una Food Policy per Roma, 2019. https://www.politichelocalicibo.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Una-Food-Policy-per-Roma.pdf.

- Marino, D., & Mazzocchi, G. L’evoluzione della Food Policy a Roma: quali scenari?. Re| Cibo, 2022, 1.1.

- Cannata, G., Cavallo A. Ripensare Roma e il suo sistema agroalimentare, in Rapporti Collana Ateneo, Unversitas Mercatorum, Giapeto Editore, 2021.

- Cavallo, A., Di Donato, B., Guadagno, R., & Marino, D. The agriculture in Mediterranean urban phenomenon: Rome foodscapes as an infrastructure. In: Finding Spaces for Productive Cities. In: Proceedings of the 6th AESOP Sustainable Food Planning Conference.-AESOP/VHL. 2014. p. 213-230.

- Cavallo A., Marino D. Assessing the connections between farming, food, and landscape planning in the development of sustainable urban policies: the case of Rome. In: Proceedings of international conference on “changing cities”: spatial, morphological, formal & socio-economic dimensions. Grafima, Thessaloniki. 2013.

- ISTAT. 7° Censimento generale dell’agricoltura, Istat, Roma, 2022.

- Munafò, M. (a cura di), 2022. Consumo di suolo, dinamiche territoriali e servizi ecosistemici. Edizione 2022. Report SNPA 32/22.

- López-Ridaura, S., Masera, O., & Astier, M. Evaluating the sustainability of complex socio-environmental systems. The MESMIS framework. Ecological indicators, 2002, 2.1-2: 135-148.

- Resare Sahlin, K., Carolus, J., von Greyerz, K., Ekqvist, I., & Röös, E. Delivering “less but better” meat in practice—a case study of a farm in agroecological transition. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 2022, 42.2: 24.

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M., and Ganuza-Fernandez E. We don’t want to be officially certified! Reasons and implications of the participatory guarantee systems. Sustainability, 2018, 10.4: 1142.

- Marino, D., Mastronardi, L., Giannelli, A., Giaccio, V. and Mazzocchi, G. Territorialisation dynamics for Italian farms adhering to Alternative Food Networks. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 2018, 40: 113-131.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).