1. Introduction

Physical activity and healthy lifestyle are important elements of children’s everyday life. This is especially true for those with chronic disease, e.g., asthmatic children. In recent decades number of patients suffering from asthma and other respiratory disorders has continuously increased not only in Hungary but all over the world as well. In 2015, number of registered asthmatic patients in Hungary was more than 290.000, which indicates a 2.94% prevalence. Prevalence of asthma has increased as well, since it was 1.28% in 2000, 2.47% in 2010, while in 2015 it was 2.94% [

1,

2]. Endre and coworkers published several studies about the prevalence of childhood asthma in 2007, where Budapest showed a 1.5-times increase between 1995 and 2003 [

3]. Comparing these numbers to the 5-6% of European prevalence data, the Hungarian values were significantly lower [

4,

5]. The reason for this could be the lack of reporting obligation in Hungary, since asthmatic children under the age of 18 and those patients who were not treated at pulmonology departments were not reported [

6]. Interestingly, the prevalence of asthmatic patients who participated in follow-up examinations and got treated by pulmonologists because of their severe asthma, was very close to international data [

7]. Subsequently, the real prevalence of asthmatic patients in Hungary was estimated between 4-10% by Kontz and coworkers in 2016 [

6]. The prevalence of childhood asthma has been increasing continuously. In 2017, Mirzaei and coworkers conducted a meta-analysis based on 50 studies about the prevalence of asthmatic children in Middle East countries [

8]. Based on the data of 289.717 children under the age of 18, the prevalence of childhood asthma was 7.53%. Prevalence of childhood asthma in the USA doubled between 1980 and 1995 followed by a slight increase between 2001 and 2010 [

9]. Several international studies proved the benefit of climate therapy on respiratory functions among asthmatic children [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The goal of different therapeutic approaches is not only to treat the disease but to improve patients’ quality of life as well. Studies examining well-being and quality of life started in the 70s [

19,

20]. In Hungary a wide range of work investigated the quality of life on asthmatic patients [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Asthma-related surveys specialized to childhood asthma are more often used in clinical trials [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Long-term consequences on the quality of life was assessed by examining 105 adults who suffered from childhood asthma, their exercise habits were inhibited [

35].

Therefore, we conducted our site initiated study among asthmatic children at the University of Debrecen, Department of Pediatrics. Exercise habits, favourite sports, and several obstacles that inhibit their physical activity were examined. The correlation between the severity of the disease, the body mass index of the children, and their physical activity were analyzed, and, furthermore their parents’ opinion whether or not the children should participate in active sports was also examined.

The aim of the study is to show the extent to which the mindset that a chronic illness is a barrier to physical activity exists in our society. There are two aspects of this question in our study. The first is whether children with asthma are willing to engage in physical activity and whether this affects their social integration. The other is the extent to which parents inhibit or support their children to be active in sports. We were curious to see if any correlation could be detected between the severity of the disease and the child’s physical activity and the closely related BMI.

We hypothesized that children with asthma practice less physical activity than their healthy peers, driven by fear of performance and parental concern about worsening symptoms. We further hypothesized that the more severe the disease, the less physical activity the child performs and that this is associated with an altered BMI. We also hypothesized that there are no gender differences in the above findings.

Our study fills a niche in that no such study has been conducted in this disadvantaged region of Eastern Hungary, where the level of education and per capita income is lower compared to other parts of the country, moreover unemployment and the prevalence of chronic diseases are higher than the national average.

2. Materials and Methods

Physical activity of children with asthma treated at the Department of Pediatrics of the University of Debrecen was analyzed by questionnaires and activity-measuring armbands. The Asthma Questionnaire was previously validated on an international level. Our special questionnaire for physical activity was validated and compared to the international IPAQ questionnaires in our previous studies [

36,

37]. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and was approved by the Medical Research Council of Hungary (ETT-TUKEB: 24634-4/2018/EKU).

2.1. Study design

We asked 4 questions about sociodemographic data, followed by 8 questions related to sporting habits in the form of multiple-choice answers. The questionnaire was answered by the parents, i.e., how often, what, where and with whom the child likes to play sports and what is the motivation to be physically active. One more question was asked about the reasons for not playing sport, where several answers could be ticked. This was followed by 11 statements on the relationship between physical activity and asthma, and on the characteristics of the child’s participation in physical education classes at school. In these cases, a 5-point scale was used to indicate the extent to which the parents agreed with the statements. The Asthma Control Test was the last part of the questionnaire, where we asked about the characteristic parameters of the last 4 weeks in relation to asthma included the data on respiratory function and physical status recorded by the pediatric pulmonologist. The whole survey was voluntary.

2.2. Participants

93 parents and their children were involved in the survey, while 20 children were given a wrist-worn armband (Xiaomi Mi Band 2, Xiaomi Corporation, China; readout: steps in every minute) to monitor daily physical activity. Nine out of the twenty adhered to the two-week-long test without removing the armband or stopping the measurement. Extracurricular sport was defined as a continuous physical exercise that lasted at least 30 minutes. The average age of children was 12.6±3.5 years (mean±SD), 69.9% were boys, 30.1% were girls. After the Covid-19 pandemic, 16 children of the 93 who were still followed by the Pediatric Department, and those patients repeated the filling in the same questioner and medical assessment.

2.3. Data analysis

The completed questionnaires were processed using EvaSys software (VSL Inc., Hungary;

http://www.vsl.hu). Responses were analyzed by gender and age group. SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 29.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The normal distribution of the data was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test. In the case of multiple responses, frequency was analyzed using Multiple Response Frequencies and the correlation between groups was examined using Multiple Response Crosstabs. The Pearson’s chi-square test or Fischer’s Exact test was used for compare of proportions. The significance of differences between groups was assessed using Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test or the paired Student’s t-test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-economic factors influencing sports behavior

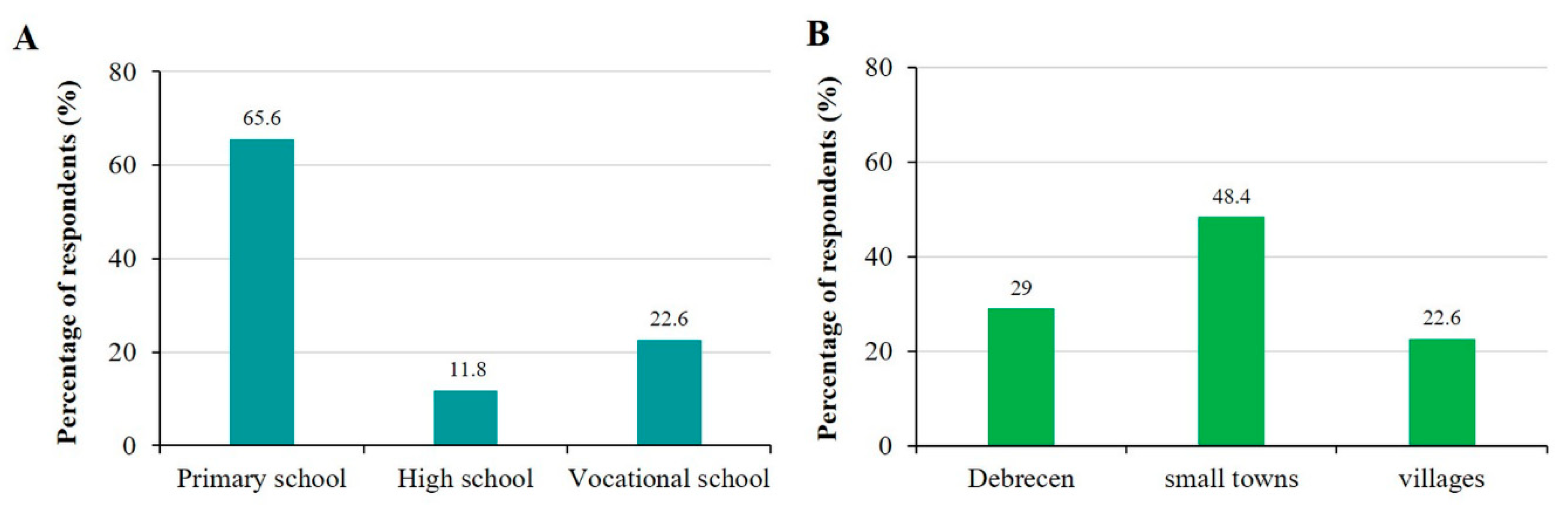

Close to one third of children studied in primary school, while the rest of them studied in different types of high schools (high school, technical college, technical school) (

Figure 1A). Less than one third of the subjects lived in the county center Debrecen, almost half of them lived in different towns while the rest lived in villages (

Figure 1B). Analysis by residence showed no significant difference between proportion of those engaged in physical activity (55%, 46.7% and 74.1%; villages, towns and Debrecen, respectively; p=0.075), participation in PE classes (100%, 91.1% and 92.3%; villages, towns and Debrecen, respectively; p=0.397) and physiotherapy (9.5%, 8.9% and 19.2%; villages, towns and Debrecen, respectively; p=0.401). We investigated the relationship between sport of choice and place of residence, but did not find a significant association. In terms of reasons for physical inactivity, we observed that inactivity due to lack of facilities is significantly more common among children living in villages (p=0.028; Chi-square test).

48.4% of the families reported good standard of living including financial savings. 45.1% could cover all their expenditures without being able to save money. Only 2.2% of the subjects reported poor living circumstances and suffered from poverty in their everyday lives.

3.2. Physical and health status participation children

BMI of children varied within a wide range (12.33 & 37.37; minimum & maximum, respectively). Based on their BMI, 24 children were considered overweight, while 13 of them were underweight. However, mean value of BMI normalized to their ages was 54±34% which corresponded to the values of healthy children at the same age. We also examined the relationship between children’s BMI status and their physical activity, but no significant difference was found between the groups (p=0.398, Chi-square test). The percentages of children doing and not doing physical activity were almost the same in all groups. Furthermore, the analysis of BMI status also revealed that no significant difference between their participation rates in physical education (91.2%, 95.7%, 85.7% and 100%; underweight, normal, overweight and obesity, respectively; p=0.698) and physiotherapy (17.1%, 10.9%, 0% and 0%; underweight, normal, overweight and obesity, respectively; p=0.548). When comparing the BMI status of different sports, we found significant differences for cycling (p=0.046) and gymnastic (p=0.016). For both, we observed that underweight children chose these sports more often than their overweight counterparts. Examining the association between reasons for physical inactivity and BMI status, we observed that significantly more children with normal BMI did not play sports due to lack of time (p=0.008). Moreover, the analysis shows that children with asthma who are overweight are more likely to be recommended by their doctor not to be physically active (p=0.007).

Conclusions were similar upon examining respiratory parameters (vital capacity, VC; forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1; and forced expiratory flow at 25% to 75%, FEF25-75). Minimum and maximum values of VC, FEV1 and FEF25-75 normalized to the expected age-related values were 24 and 123%, 39.6 and 140%, 22.7 and 128%, respectively. As expected, strong correlation was detected between the values of FEV1, and FEF25-75 (r2 = 0.524). Also, mean value of FEF25-75 (74.4±21.6%) was significantly lower compared to the expected value at that age. However, there was no correlation neither between BMI and FEV1, (r2 = 0.0004) nor between BMI and FEF25-75 (r2 = 0.0002), respectively. Upon examining the data from the armbands, a typical recording is shown in

Figure S1, it became clear that the number of steps per day varied greatly among the children, from 6029 to 13,981 on average over the two weeks. Overall, the average over the nine children participating in the study was 9235±2645 steps/day.

3.3. Sporting habits of children with asthma

56.5% of the children reported regular physical activity besides PE classes. 46.3% performed physical exercise once or twice a week, 38.9% three-four times a week, while 11.1% of them exercised at least five times a week.

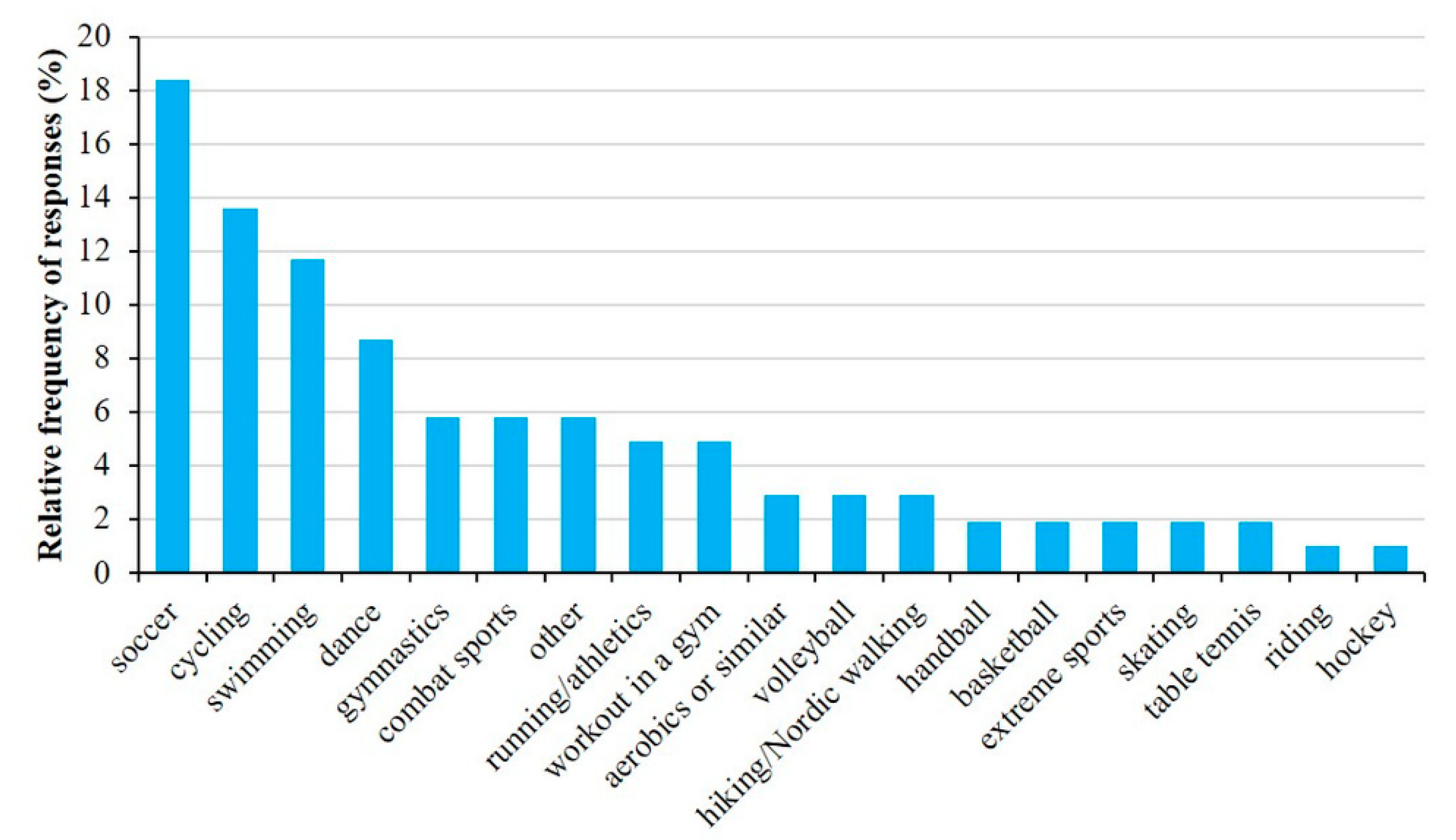

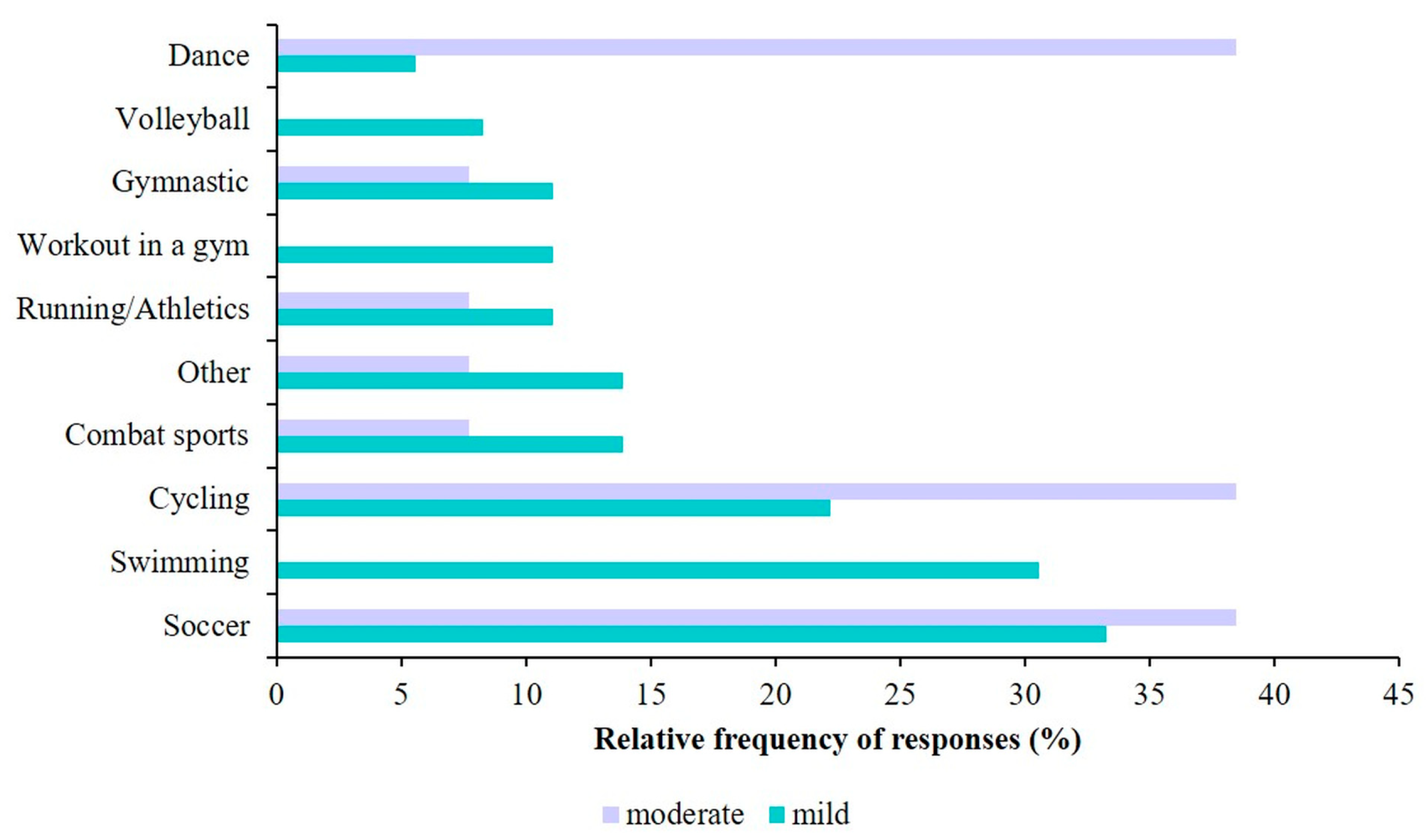

Most common forms of physical activities (

Figure 2) were soccer (18.4%), cycling (13.6%), swimming (11.7%) and dancing (8.7%). Children usually exercised in school (26.9%) as part of their afternoon activities or in different sport clubs (21.5%). Some exercised at home or chose outdoor activities.

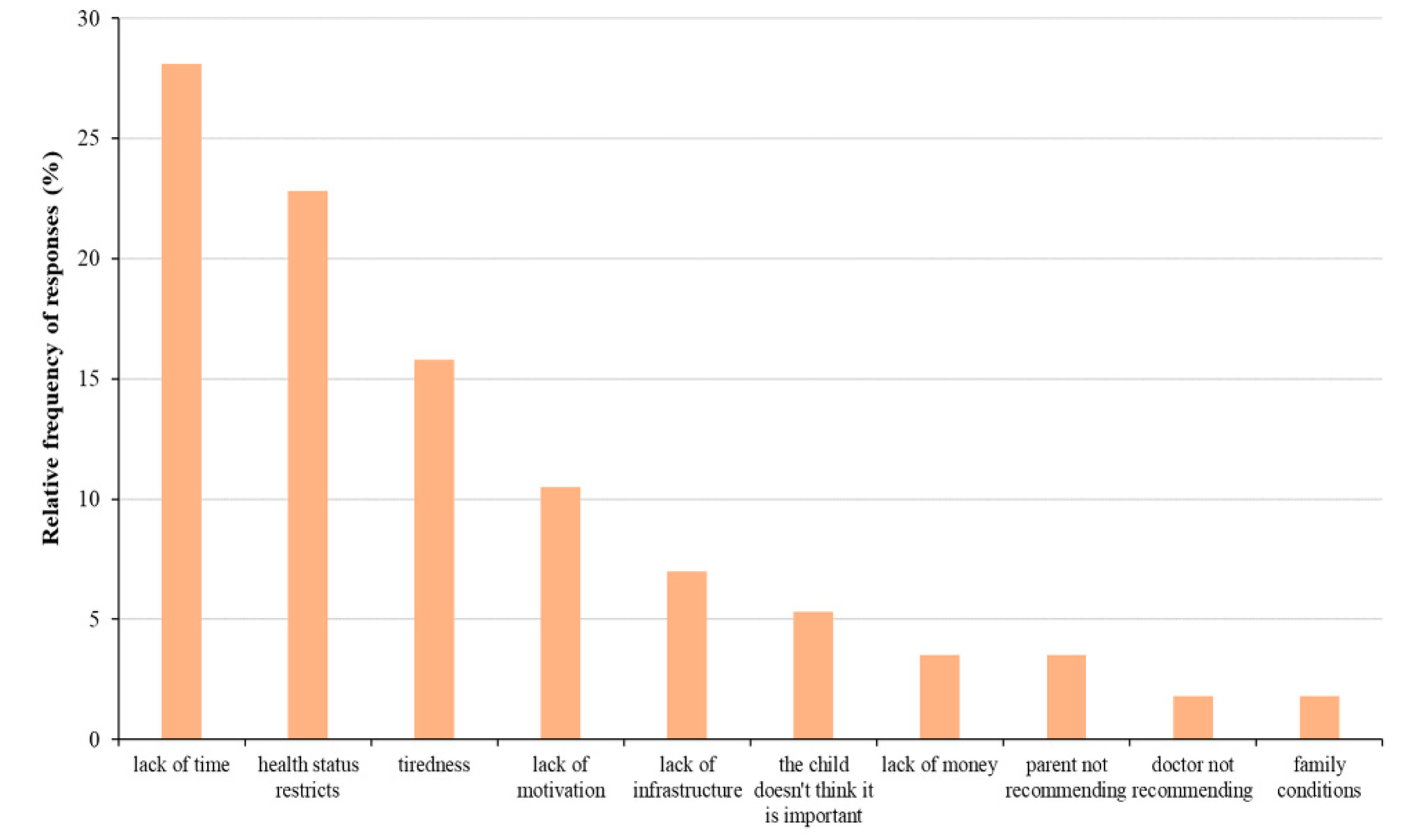

However, even those who did not exercise regularly performed frequent physical activity such as cycling or walking. More than likely, this was due to the fact that most of the subjects lived in small towns where cycling or walking were the most common forms of travel. It is important to note that except for 6.6%, almost all children participated in PE classes. In correlation to that, percentage of children going to physiotherapy was very low, only 12%. However, percentage of children who did not exercise due to their health status was very high (22.8%) among those who did not perform regular physical activity. Lackof time (28.10%), tiredness (15.8%) and lack of motivation (10.5%) were the other most common reasons for physical inactivity (

Figure 3).

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between asthma severity and physical activity, we found a significant association that the number of children doing physical activity decreases significantly with increasing asthma severity (p=0.035; Chi-square test).

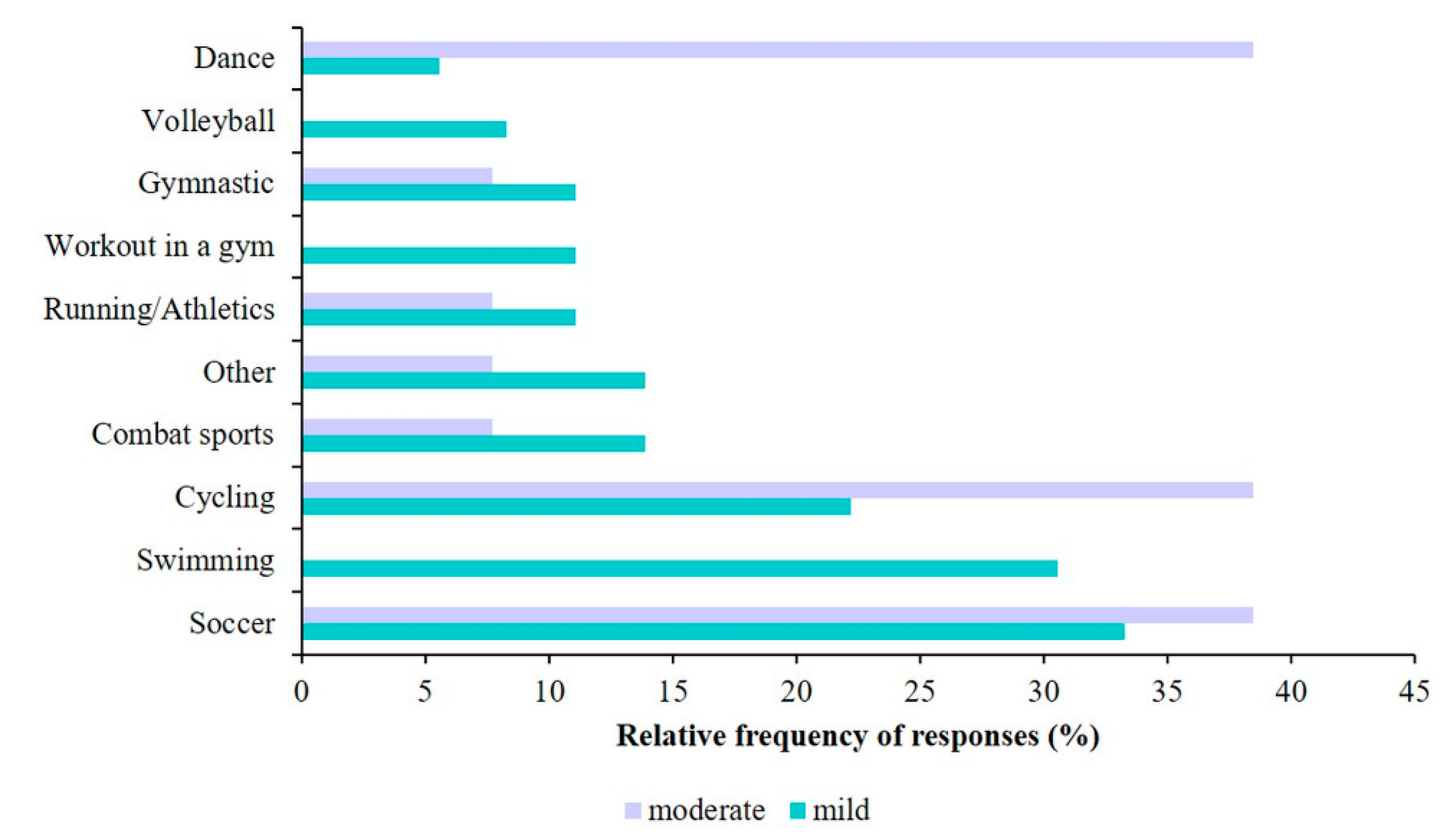

In terms of different types of sports,

Figure 5 presents the most common activities performed by children with mild and moderate asthma. A significant difference between the two groups were only found for swimming (p=0.018; Chi-square test). Regarding participation in PE classes and asthma status, significantly more children with mild (62.3%) and moderate asthma (37.7%) participate in PE classes, while children with severe asthma (16.7%) are typically do not attend PE classes at school (p=0.002; Chi-square test). However, we did not find a significant difference between participation in physiotherapy and asthma status (p=0.140; Chi-square test). Analyzing the association between the reasons for physical inactivity and asthma status, we observed that the only significant difference among the different groups was in physical inactivity due to health status (p=0.023).

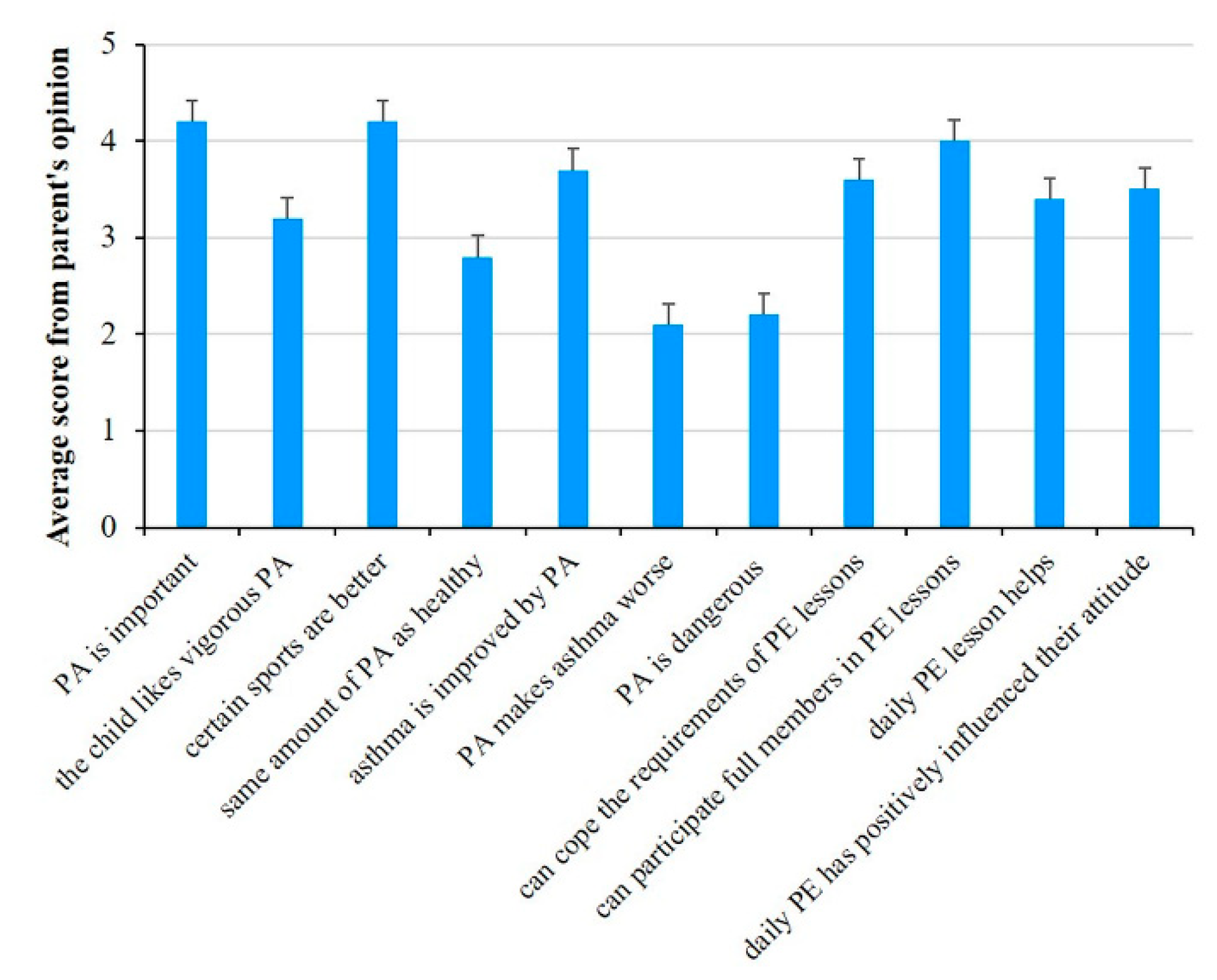

3.4. Parents’ opinion on the physical activity of their children

77.2% of parents found the role of physical activity important for asthmatic children. However, only 56.5% said that physical activity could improve the disease.

56.1% of parents believed that their children could meet all the requirements of PE classes. Similarly, percentage of parents was about the same who believed that their children could participate in PE classes just like everyone else (

Figure 6).

Differences in parents’ responses between those whose children exercised regularly versus those whose did not is worth consideration. Those parents and their children who exercised regularly believed that physical activity was important for asthmatic children, improved the asthma and could participate in PE classes with the group just like healthy children (

Table 1). In contrast, the latter group’s judgement on these points were not so positive (3.89, 3.33, and 3.49, respectively). Rating the significance of everyday exercise was also different among the two groups of parents. Parents of those children who exercised regularly said that daily PE classes had improved the health status of their children and positively affected their attitude toward physical activity. On the other hand, parents of those children who did not exercise regularly thought that effect of daily PE class was negligible (2.95 and 3.05, respectively). The statistically significant differences between groups of children whose regularly participate in physical activity and those whose did not are shown in

Table 1. Significant p-values are indicated in bold and italic and p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

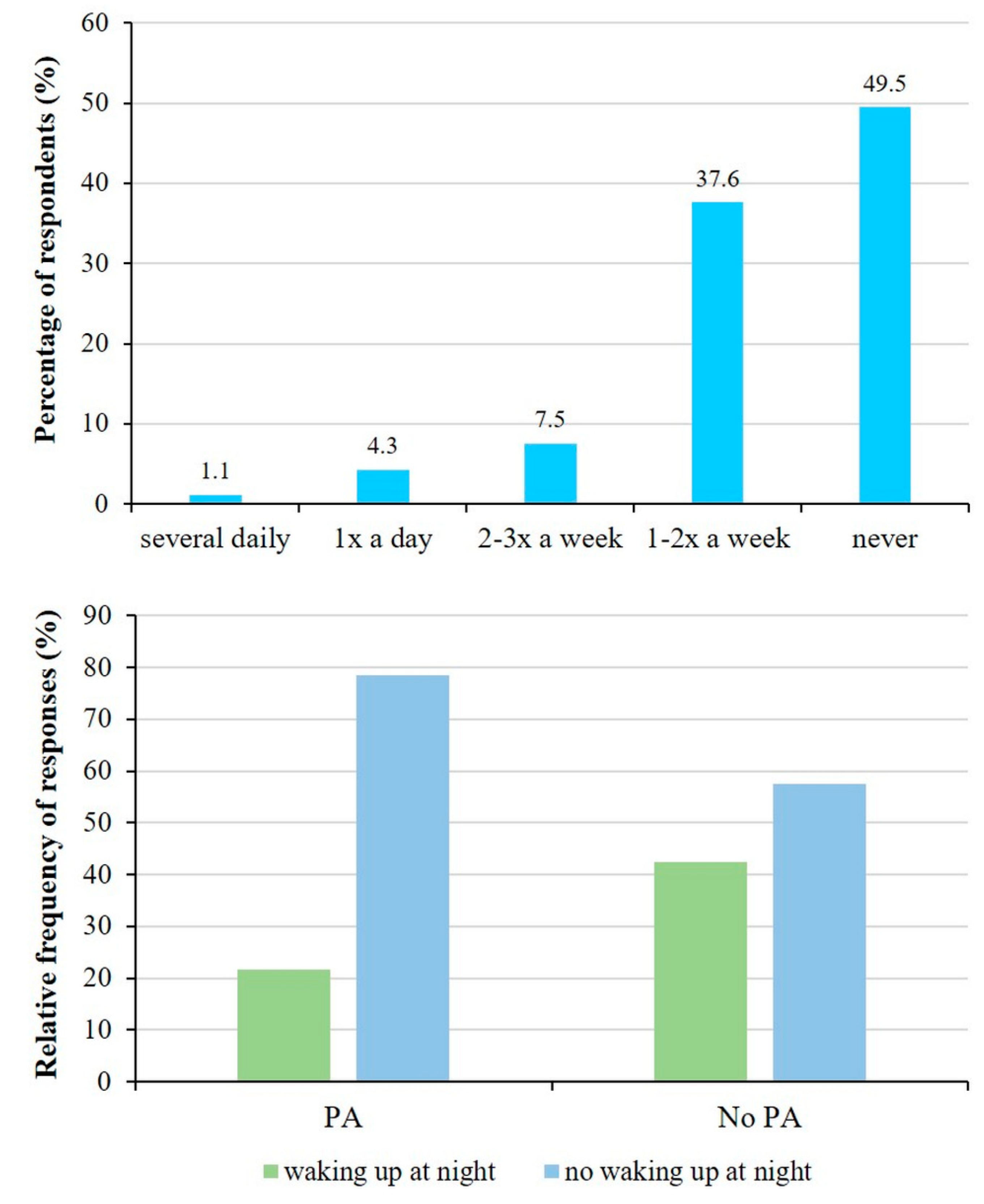

3.5. Impact of illness on children’s quality of life

Close to half of the subjects reported that their child indicated no asthma-related dyspnoe during the last four weeks. Little over one third suffered from that once or twice a week, while only one child suffered more than once a day (

Figure 7).

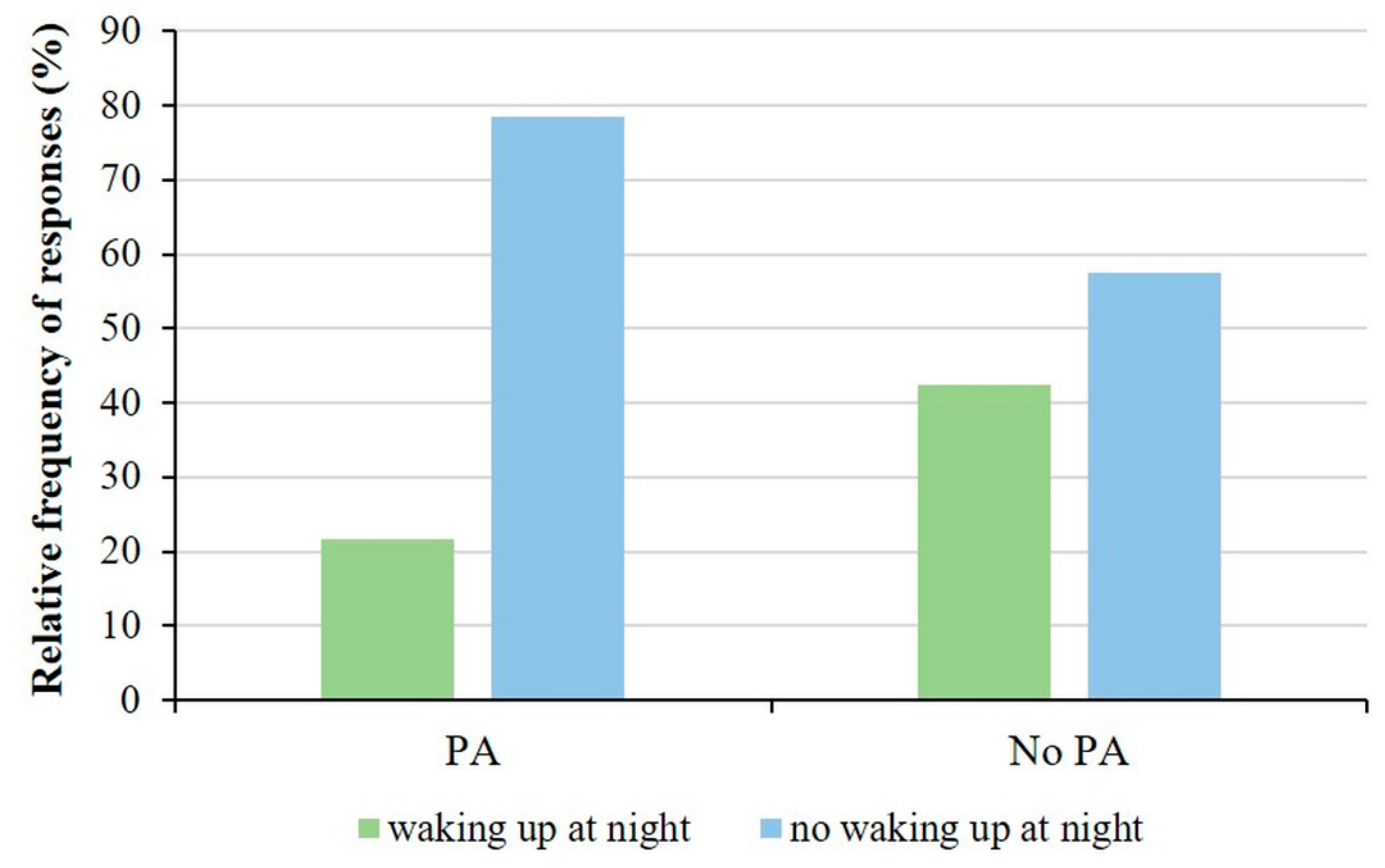

Studying the association between physical activity and sleep disturbances, we observed that 21.6% of children who participated in sports activities woke up at night or earlier than their usual wake-up time in the morning with asthma symptoms, while 78.4% did not wake up. In contrast, 42.5% of children who do not play sport have sleep-disrupting asthma symptoms. Reconsidering the options given in the questionnaire, we created 2 groups, children who wake up at night for asthma symptoms and children who do not wake up. Thus, when performing the analysis, we observed a significant difference between the physical activity group and the frequency of asthma symptoms that cause sleep disturbances (p=0.041; Fisher’s exact test,

Figure 8).

Analyzing the association between physical activity and asthma attacks, we did not find a significant correlation. 19.2% of children who were physically active used only the asthma medication, while 80.8% had not used it once in the 4 weeks before completing the questionnaire. On the other hand, 40% of children who did not play sport used their medicine and 60% did not use it at all.

3.6. Gender based analysis of physical activity of children with asthma

Separate analysis of the answers from boys and girls showed no significant difference between the rate of their physical exercise (50.0% and 59.4%; girls and boys, respectively), participation in PE classes (96.3% and 92.2%; girls and boys, respectively) and in physiotherapy (14.8% and 10.8%; girls and boys, respectively). However, similarly to healthy children at the same age [

37,

38,

39], their choice of exercise type differed significantly. Girls mostly preferred dancing (25%) and gym (10.7%), while boys rather chose soccer (26.2%) and cycling (20%). The relative frequency for physical activity type by gender are summarized in

Table 2 and significant differences are indicated in bold and italic. Parents of boys and girls agreed that physical activity was important for asthmatic children (4.22 and 4.19, weighted average of points on a 1-5-point-scale; for girls and boys, respectively), and that certain sports were better for them (4.11 and 4.21; for girls and boys, respectively). However, judgement of physical activity was very different among the parents. Parents having boys thought that physical activity could improve their sons’ health status (3.8) and they could participate in PE classes just like healthy children (4.17). However, this was not obvious for parents having girls (3.32 and 3.74, respectively).

Table 3 shows the summaries of the responses. Parents of girls are significantly less likely to agree (2.33) with the statement that children with asthma can do the same amount of physical activity as their healthy peers (p=0.023). Parents of boys disagree that physical activity is dangerous for children with asthma (2.05), while parents of girls are more neutral (2.68) and the difference is statistically significant (p=0.020). Furthermore, parents having boys believed that the introduction of daily physical education had improved their child’s health (3.54 and p=0.042). We analyzed the relationship between the causes of physical inactivity and gender but we did not find a significant association.

3.7. Cross correlations between dependent and independent variables

Overall, the results of our study show that regular physical activity and participation in PE classes are highly dependent on the severity of asthma in children (

Section 3.3.). Choice of sport is influenced by gender (

Table 2), BMI status (

Section 3.2.), and asthma severity (

Figure 5). In addition, the reasons for not doing sport are influenced by BMI status (

Section 3.2.), asthma severity (

Figure 4), and the place of residence (

Section 3.1.).

3.8. Results of follow up examinations

In the case of 16 children, it was possible to compare the values of asthma related parameters measured in 2019 with those identified in 2023. We examined BMI trends and observed significant changes. Comparing the values of vital capacity and FEV1, we observed higher values on average in 2023, but the change was not significant. However, when comparing the FEF25-75 parameters, we observed a reduced average value in 2023, although the difference was not significant.

Table 4 reports results for the comparison of the asthma related variables in the study group.

4. Discussion

In the past 50 years, several studies analyzed the effect of physical activity on childhood asthma [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Many studies suggested regular physical activity to asthmatic children [

48,

49], since it could improve both their physical conditions, their social interactions and their development as well [

50]. Several studies proved that obesity aggravated the severity of asthma and attenuated the quality of lives [

42,

51,

52,

53] strongly suggesting proper diet and regular physical activity [

54]. Different studies examined the treatment of professional athletes’ asthma [

55], supplemented with the strategies suggested by coaches. Scientists stated that both competitive sport and physical activity were important to carry out proper lifestyle that is indispensable for both asthmatic children, adults and healthy people as well [

56]. Although several studies examined the correlation between childhood asthma and physical activity, no research has been conducted on this subject in northeast Hungary yet. In this study, we examined the exercise habits of 93 asthmatic children as well as their parents’ relation to sports. Based on our results we concluded that percentage of those who performed regular physical activity was smaller for asthmatic children compared to healthy children. While 90% of teenagers from northeast Hungary exercised regularly [

39], it was only 60% for asthmatic children participated in this study. Compared to healthy individuals, rate of physical inactivity due to improper health conditions was much higher among those, who did not exercise regularly. Similarly, international studies [

57] did not show any difference between boys and girls when examined the rate of regular physical activity. On the other hand, similar to prior observations on healthy children, the place of living greatly affected the significance of physical activity [

38]. While children in small towns and villages (supposedly due to the lack of proper infrastructure [

39]) exercised mostly in school or outdoor (38.1 and 19.0%, respectively), children in county centers exercised in sport clubs or sport facilities (33.3 and 22.2%, respectively).

One important aspect of our examination was the parents’ attitude toward the physical activity of their asthmatic children. Similarly, to our observations, findings of international studies [

58,

59] stated that mothers showed more care and worry toward their children. Interestingly, those asthmatic children and their parents who exercised regularly had a more positive attitude toward sports and daily PE classes. It raised the question whether this was the consequence of their positive experiences or the fear of those who did not exercise. Another conclusion was that parents with boys supported exercise rather than parents with girls that can be due to the fact that parents with their daughters had a tendency to take less risk. It is important to emphasize that providing proper infrastructural conditions have significant impact on free time activities. Team sports are one of the easiest ways to involve asthmatic children into physical activities [

57]. Team sports, however, require proper infrastructural conditions.

There are certain limitations of the study. Although we tried to include all patients with asthma at the Pediatric Clinic, only 93 parents agreed to participate in the study. Moreover, only 9 of the children wore the armband continuously long enough for the data to be properly evaluated. As a consequence, it was not possible to include this data in correlation analyses, we thus relayed only on the reporting of the measurement results. Due to the regional nature of the patient care, all children are residents of the Northern Great Plain region of Hungary, the applicability of our results to the Hungarian population as a whole is limited.

5. Conclusions

In our study we conducted surveys, examined respiratory functions and used special bracelets that could measure physical activity in order to assess exercise habits of asthmatic children. We concluded that sport was beneficial to children’s physical and mental well-being as well as to their development. Therefore, we have to strive that even asthmatic children could enjoy the benefits of regular physical activity. Besides providing proper infrastructural conditions, choice of appropriate sports and professional support is also necessary. Furthermore, since fear of the consequences of physical activity, and hence the choice of sport, depends largely on education, this should extend beyond the education of children and their parents and include their teachers and coaches as well.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Figure S1: Data from the armband to monitor daily activity. Each data point represents the number of steps taken in an hour long time period. Measurement started at 24 am on day 1 and covers 14 days (336 hours).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology IB, GyB, and LC; interaction with patients ÁP and GyB; formal analysis TK, ÁP, and L.C.; writing - original draft preparation, IB; writing - review and editing ÁP, GyB, and LC; visualization TK and LC; supervision IB and LC. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the EFOP-3.6.2-16-2017-00003 project. The project is co-financed by the European Union and the European Social Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Research Council of Hungary (ETT-TUKEB: 24634-4/2018/EKU).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to those children and their parents who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, M. and W.Z. Yao, [Interpretation of Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2016]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2016. 96(34): p. 2689-2691.

- Kovács, G. , Korányi Bulletin. 2016, Országos Korányi TBC és Pulmonológiai Intézet: Budapest. p. 26-35.

- Endre, L. , et al., [Increase in prevalence of childhood asthma in Budapest between 1995 and 2003: correlation with air pollution data and total pollen count]. Orv Hetil, 2007. 148(5): p. 211-6.

- Accordini, S.; Corsico, A.G.; Braggion, M.; Gerbase, M.W.; Gislason, D.; Gulsvik, A.; Heinrich, J.; Janson, C.; Jarvis, D.; Jõgi, R.; et al. The cost of persistent asthma in Europe: an international population-based study in adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 2013. 160(1): p. 93-101.

- OECD, Health at a glance 2013: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing. 2013. 212.

- Katalin, K.; Gábor, T.; Georgina, S.; Árpád, F.; Ágnes, J.; Alpár, H. Asztmás és COPD-s betegek ellátásának jellemzői a magyar egészségügyben [Characteristics of medical care of asthma and COPD patients in the Hungarian healthcare system]. Medicina Thoracalis, 2016. 69(4): p. 243-251.

- Csoma, Z.; Antus, B.; Barta, I.; Szalai, C.; Semsei, A.F.; Herjavecz, I. Severe asthma database in Hungary, initial steps. Clinical and Translational Allergy, 2013. 3(Suppl 1): p. P33.

- Mirzaei, M.; Karimi, M.; Beheshti, S.; Mohammadi, M. Prevalence of asthma among Middle Eastern children: A systematic review. Med J Islam Repub Iran, 2017. 31: p. 9.

- Akinbami, L.J., A. E. Simon, and L.M. Rossen, Changing Trends in Asthma Prevalence Among Children. Pediatrics, 2016. 137(1): p. 1-7.

- Boner, A.L.; Comis, A.; Schiassi, M.; Venge, P.; Piacentini, G.L. Bronchial reactivity in asthmatic children at high and low altitude. Effect of budesonide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 1995. 151(4): p. 1194-200.

- Valletta, E.A.; Piacentini, G.L.; Del Col, G.; Boner, A.L. FEF25-75 as a marker of airway obstruction in asthmatic children during reduced mite exposure at high altitude. J Asthma, 1997. 34(2): p. 127-31.

- Grootendorst, D.C.; Dahlén, S.; Bos, J.W.V.D.; Duiverman, E.J.; Veselic-Charvat, M.; Vrijlandt, E.J.L.E.; O'Sullivan, S.; Kumlin, M.; Sterk, P.J.; Roldaan, A.C. Benefits of high altitude allergen avoidance in atopic adolescents with moderate to severe asthma, over and above treatment with high dose inhaled steroids. Clin Exp Allergy, 2001. 31(3): p. 400-8.

- Peroni, D.G.; Piacentini, G.L.; Costella, S.; Pietrobelli, A.; Bodini, A.; Loiacono, A.; Aralla, R.; Boner, A.L. Mite avoidance can reduce air trapping and airway inflammation in allergic asthmatic children. Clin Exp Allergy, 2002. 32(6): p. 850-5.

- Straub, D.A.; Ehmann, R.; Hall, G.L.; Moeller, A.; Hamacher, J.; Frey, U.; Sennhauser, F.H.; Wildhaber, J.H. Correlation of nitrites in breath condensates and lung function in asthmatic children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 2004. 15(1): p. 20-5.

- Peroni, D.; Bodini, A.; Loiacono, A.; Paida, G.; Tenero, L.; Piacentini, G. Bioimpedance monitoring of airway inflammation in asthmatic allergic children. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr), 2009. 37(1): p. 3-6.

- Verkleij, M.; van de Griendt, E.; A Kaptein, A.; van Essen-Zandvliet, L.E.; Duiverman, E.J.; Geenen, R. The prospective association between behavioural problems and asthma outcome in young asthma patients. Acta Paediatr, 2013. 102(5): p. 504-9.

- Vinnikov, D.; Khafagy, A.; Blanc, P.D.; Brimkulov, N.; Steinmaus, C. High-altitude alpine therapy and lung function in asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res, 2016. 2(2).

- Kokov, A. , [Pulmonary function and surfactant system of the lungs after high-altitude alpine treatment of children with asthma] [Dissertation in Russian]. 1996, Stavropol State Medical Academy: Stavropol.

- Campbell, A. , Subjective measures of well-being. Am Psychol, 1976. 31(2): p. 117-24.

- Andrews FM and, R. Inglehart, The structure of subjective well-being in nine western societies.. Social Indicators Research, 1979. 6: p. 73-90.

- 21. Müller A, Balatoni I, Csernoch L, Bács Z, Bíró M, Bendíková E, Pesti A. [Quality of life of asthmatic patients after complex rehabilitation treatment]. Orv Hetil, 2018; 1103–1112.

- Káló Z and, M. Péntek, Az életminőség mérése. Egészséggazdaságtan, 2005: p. 161-189.

- Mészáros, Á. , Life Quality Measurement in Asthma Bronchial. [Életminőség-mérés asthma bronchialéban.]. LAM, 2006. 16: p. 353-359.

- Vincze G, Rascati KL, and Z. Vincze, Health-related quality of life assurance. [Egészséggel kapcsolatos életminőség-vizsgálatok.] Bevezetés a farmakoökonómiába., 2001: p. 187-209.

- Müller A and, E. Kerenyi, Javuló életminőség és költséghatékonyság - A Mátrai Gyógyintézet asztmás, szénanáthás és COPD-s betegei terápiás kezelésének hatásvizsgálata.. Economica, 2009. 3: p. 59-64.

- Müller A, Kerenyi E, and E. Könyves, Effect of Climate Therapy and Rehabilitation in Mátra Medical Institute Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce. 2011, Agroinform Kiadó. p. 40-42.

- Juniper, E.F.; Guyatt, G.H.; Feeny, D.H.; Ferrie, P.J.; Griffith, L.E.; Townsend, M. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res, 1996. 5(1): p. 35-46.

- Christie, M.J.; French, D.; Sowden, A.; West, A. Development of child-centered disease-specific questionnaires for living with asthma. Psychosom Med, 1993. 55(6): p. 541-8.

- French, D.J., M. J. Christie, and A.J. Sowden, The reproducibility of the Childhood Asthma Questionnaires: measures of quality of life for children with asthma aged 4-16 years. Qual Life Res, 1994. 3(3): p. 215-24.

- Creer, T.L.; Wigal, J.K.; Kotses, H.; Hatala, J.C.; McConnaughy, K.; Winder, J.A. A life activities questionnaire for childhood asthma. J Asthma, 1993. 30(6): p. 467-73.

- Usherwood, T.P., A. Scrimgeour, and J.H. Barber, Questionnaire to measure perceived symptoms and disability in asthma. Arch Dis Child, 1990. 65(7): p. 779-81.

- Mishoe, S.C.; Baker, R.R.; Poole, S.; Harrell, L.M.; Arant, C.B.; Rupp, N.T. Development of an instrument to assess stress levels and quality of life in children with asthma. J Asthma, 1998. 35(7): p. 553-63.

- le Coq, E.M. , et al., Reproducibility, construct validity, and responsiveness of the “How Are You?” (HAY), a self-report quality of life questionnaire for children with asthma. J Asthma, 2000. 37(1): p. 43-58.

- Rosier, M.J.; Bishop, J.; Nolan, T.; Robertson, C.F.; Carlin, J.B.; Phelan, P.D. Measurement of functional severity of asthma in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 1994. 149(6): p. 1434-41.

- Szabó, A. , Asztmás gyermekek és szüleik életminősége és pszichés állapota., in Klinikai Orvostudományok Doktori Iskola.. 2009, Semmelweis Egyetem.: Budapest. p. 110.

- Balatoni, I.; Szépné, H.V.; Müller, A.; Kovács, S.; Kosztin, N.; Csernoch, L. Sporting habits of university students in Hungary.. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity, 2019. 11(6): p. 27-37.

- Szépné Varga H, Csernoch L., and I. Balatoni, E-sports versus physical activity among adolescents. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity, 2019. 11(6): p. 38-47.

- Szépné Varga H and, I. Balatoni, Exploring the background conditions for playing sports of pre-school children.. Tér gazdaság, ember, 2018. 6(4): p. 119-135.

- Balatoni I, Szépné Varga H, and L. Csernoch, Free Time Activities of High School Students: Sports or Video Games?. Athens Journal of Sports, 2020. 7(2): p. 141-154.

- Wanrooij, V.H.M.; Willeboordse, M.; Dompeling, E.; Van De Kant, K.D.G. Exercise training in children with asthma: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med, 2014. 48(13): p. 1024-31.

- Endre, L. , [Physical exercise and bronchial asthma]. Orv Hetil, 2016. 157(26): p. 1019-27.

- Pianosi, P.T. and H.S. Davis, Determinants of physical fitness in children with asthma. Pediatrics, 2004. 113(3 Pt 1): p. e225-9. [CrossRef]

- van Gent, R. , et al., No differences in physical activity in (un)diagnosed asthma and healthy controls. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2007. 42(11): p. 1018-23. [CrossRef]

- Hollmann, W. , [Exercise, training and sports in children with asthma from the sports medicine viewpoint]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd, 1985. 133(12): p. 863-7.

- Kemper, P. , [Asthma and sport--risk and chance]. Pneumologie, 2008. 62(6): p. 367-71. [CrossRef]

- Todaro, A. , [Physical activities and sports in asthmatic patients]. Minerva Med, 1983. 74(22-23): p. 1349-56.

- Aggarwal, B., A. Mulgirigama, and N. Berend, Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: prevalence, pathophysiology, patient impact, diagnosis and management. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med, 2018. 28(1): p. 31.

- Leonard, J.C. , [Is the asthmatic child able to play sports?]. Arch Pediatr, 1999. 6(4): p. 465-8.

- Cserhati, E. , et al., [Asthma bronchiale and sport (author’s transl)]. Allerg Immunol (Leipz), 1981. 27(1): p. 40-7.

- Trzcieniecka-Green, A., K. Bargiel-Matusiewicz, and A. Wilczynska-Kwiatek, Quality of life and activity of children suffering from bronchial asthma. Eur J Med Res, 2009. 14 Suppl 4(Suppl 4): p. 147-50.

- Milanese, M., E. Miraglia Del Giudice, and D.G. Peroni, Asthma, exercise and metabolic dysregulation in paediatrics. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr), 2019. 47(3): p. 289-294. [CrossRef]

- Story, R.E. , Asthma and obesity in children. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2007. 19(6): p. 680-4.

- Papamichael, M.M. , et al., Weight Status and Respiratory Health in Asthmatic Children. Lung, 2019. 197(6): p. 777-782. [CrossRef]

- Peroni, D.G., A. Pietrobelli, and A.L. Boner, Asthma and obesity in childhood: on the road ahead. Int J Obes (Lond), 2010. 34(4): p. 599-605. [CrossRef]

- Picconatto, W.J., S. K. Ross, and A.M. Carlson, Athletes and asthma. Minn Med, 2010. 93(12): p. 33-6.

- Fitch, K.D. and S. Godfrey, Asthma and athletic performance. JAMA, 1976. 236(2): p. 152-7.

- Winn, C.O.N. , et al., Perceptions of asthma and exercise in adolescents with and without asthma. J Asthma, 2018. 55(8): p. 868-876. [CrossRef]

- Dantas, F.M. , et al., Mothers impose physical activity restrictions on their asthmatic children and adolescents: an analytical cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 2014. 14: p. 287. [CrossRef]

- Tiggelman, D. , et al., Maternal and paternal beliefs, support and parenting as determinants of sport participation of adolescents with asthma. J Asthma, 2015. 52(5): p. 492-7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).