1. Introduction: A long-term study of nursing values, psychological strengths, stress factors and nursing careers

This study explores how a group of hospital nurses in England have confronted the challenges associated with providing COVID-19 care, a role characterized by its difficult and demanding nature requiring specialised nursing techniques, high death rates of patients, and dangers of infection to nursing staff. This role encompasses not only the clinical tasks of caring for severely ill patients but also the emotionally taxing responsibility of comforting those facing the end of life. Front-line healthcare personnel in the UK and other regions have faced an increased risk of contracting COVID-19, with more than 800 nurses losing their lives to the virus between March 2020 and February 2021, acquired directly or indirectly during their nursing duties [

1,

2]. How do nurses who have endured such challenging conditions manage their moral and psychological well-being? We speculate that a significant part of their resilience can be attributed to their unwavering commitment to a set of nursing values, such as the ‘6Cs,’ which are further elaborated below.

The follow-up study of nurses in Northern England reported here was undertaken from August 2020 to July, 2023. This study was conducted following the initial phase of the COVID pandemic but overlapped with the onset of the ‘second wave.’ In the early months of 2020, prior to and during our investigation, 4,671 individuals aged 20 to 64 succumbed to COVID-19 in England and Wales. Among women in the general population this resulted in a death rate of 9.7 per 100,000. However, among female nurses, the COVID-related death rate was recorded at 15.3 per 100,000, which was 1.58 times higher than in the general population [

1]. The first wave of COVID-19 infections began during the first quarter of 2020 when nurses in English hospitals often lacked access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and masks [

3].

The of COVID-19 presented a formidable professional challenge for our interviewees (whom we had first interviewed in 2018, prior to the pandemic) with more than two-thirds actively and continuously engaged in daily COVID care; all had some contact in their daily practice with Covid patients, or their grieving relatives. It is well-documented that nursing during an infectious disease epidemic is arduous and demanding [

4] and the epidemic nearly overwhelmed healthcare staff in NHS hospitals in England from December 2020 through February 2021 [

5].

As Waddington [

6] aptly described, during this second wave, frontline nurses confronted a daily ordeal of “anxiety and dread within a single 12-hour shift.” What stood out in these firsthand accounts, drawn from The Royal College of Nursing and its members, was the remarkable courage and unwavering determination exhibited by nurses in fulfilling their roles “ [

7]. This observation invites the question: What may have served as the wellspring of this unwavering resolve, courage, and moral purpose? This has been explored in the longitudinal study of nurses, reported below.

This paper is the third report from a study examining personality, stress, values, role performance, and career outcomes among a cohort of female hospital nurses [

8,

9]. We offer a psychometric analysis of how a ‘special’ sample of English nurses managed the exceptionally stressful task of caring for COVID-19 patients. Our intuition (as professional nurses) is that the roles of the COCID-care nurses we studied have a value-grounded and subjective (personality-based) set of guiding principles and motivations which are different from those which the institution conventionally assumes [admin]. Many nurses have motivations and career values which are implicit, but are nevertheless strongly held. [

10,

11,

12,

13]

2. Nursing values

Nursing is a vocation that best suits an individual whose personality and personal principles play a crucial role in their ability to handle the demanding responsibilities of healthcare [

14] The core principles of a nurse’s calling are encapsulated in “the 6Cs of nursing”: Care, Compassion, Competence, Communication, Courage, and Commitment. These six values have been acknowledged (but rarely operationalized) in nursing and midwifery [

15], and most saliently by the Royal College of Nursing [

16]. These enduring values trace their roots to the pioneering work of Florence Nightingale, who revolutionized nursing care, practices based on her experiences caring for war-wounded patients in the 19th century [

17].

A similar professional ethos in nursing was forged in North America by nurses who tended to Civil War casualties [

18]. In the evolution of this “philosophy of care in nursing,” both within the United States and on an international scale, there is also a prominent spiritual or religious dimension [

15,

19].

In the UK model of nursing values, nursing places Care as its foundational core, with nurses serving as both caregivers and sources of comfort for individuals experiencing a range of life-altering transitions, which may encompass moments of stress and even moments of joy. These transitions can include instances of injury, the miracle of birth, the journey to recovery, the process of rehabilitation, the provision of end-of-life care, and the facilitation of a peaceful passing.

Compassion, a crucial attribute in nursing, encompasses a combination of inherent and learned qualities that include intelligence and empathetic insight into each patient’s fears, anxieties, sufferings, and hopes.

Competence in nursing extends beyond the acquisition of technical skills; it also involves the ability to excel in nursing practice and collaborate effectively within complex medical care teams. This competence empowers nurses to optimize their unique professional abilities and to adapt and integrate new techniques and technologies into their care delivery.

Effective communication encompasses actively listening to both patients and colleagues while also expressing one’s own perspectives on patient care to fellow team members and superiors. It involves openly extending support to both colleagues and patients when they find themselves in stressful situations.

Courage entails unwavering resilience when confronted with challenging scenarios, the ability to handle the suffering of others, and the bravery to explore and implement innovative approaches to enhance patient care.

Commitment is a deep-seated devotion not only to patients but also to acquiring and applying new skills and cutting-edge technologies. It also encompasses a dedication to comprehending the inner workings of the organization in which one operates. This insightful understanding, in turn, facilitates the smooth functioning of the organization.

Communication involves listening to others – patients and colleagues – and communicating one’s own needs and understandings of patient care to colleagues and to line managers, openly offering support to both colleagues and patients in stressful situations. Courage involves steadfastness in the face of stressful situations, coping with the suffering of others, with courage to think of (and implement) new ways of optimising patient care.

In order to measure the six kinds of value dedication in nursing, we constructed a nursing values questionnaire (NVQ) whose psychometric validity has been explored in the report of the initial study of the cohort of nurses [

8]

3. The Critical Realist research model, and the study’s first phase

We began this research by employing a critical realist perspective, which is a value-driven approach that intuitively discerns the underlying nature of the research domain. This approach enables us to develop nuanced insights through meaningful dialogues with research participants, with the ultimate goal of fostering morphogenesis—a constructive social transformation of institutions and interactions within them [

20,

21].

Critical realism has evolved into a widely adopted methodology in the fields of education, social welfare and healthcare management, as evidenced by studies spanning from Alderson’s work in 2015 to 2021 [

22,

23]. Critical Realism (CR) has gained significant appeal among social researchers and theorists who advocate for a strong ideological foundation in understanding human behaviour. It posits that certain structures, such as class exploitation, metaphysical moral codes, and the associated systems governing societal relationships, are real but often unacknowledged or unrecognised. While the nature and intricate details of these structures may be subject of examination and debate, their existence (ontology) is firmly established [

21].

In the context of the Critical Realism (CR) framework, key figures, including UK nurse leaders such as Mulholland in 2020 [

24] have played a pivotal role in promoting a dialectic between marginalized groups, like frontline nurses, and individuals and organizations advocating on their behalf. This dialogue serves to unveil the societal forces at play in the exploitation of nursing staff. For instance, Dame Anne Marie Rafferty, the President of the Royal College of Nurses, has articulated that the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a catalyst for addressing the systemic issues afflicting the nursing profession.

Dame Rafferty highlighted several critical concerns, including the persistently low and declining wages for nursing staff, inadequate nurse-patient ratios leading to a significant exodus of trained personnel from the profession, and a deficiency in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) opportunities for nurses. A study from the Royal College of Nurses (RCN), involving 1,600 nurses who left the profession, revealed that approximately a quarter of them departed due to the sustained stress related to personal adaptation challenges and mental health issues, as documented by Hackett in 2020 [

25].

During the initial phase, one of the heuristic approaches employed involved data reduction, eliminating some overlapping measures with the aim of reducing the number of variables needed as a preliminary to exploring a meaningful typology of hardiness and vulnerability in nurses. This approach yielded relatively successful results, categorizing individuals into four distinct types based on their nursing careers (

Table 1). The first category included very successful “hardy personality” career nurses who demonstrated the ability to effectively manage a wide range of professional and personal challenges. The second and third categories comprised successful nurses who were essentially “soldiering on,” falling within the middle range of adjustments and outlook. The final group consisted of individuals clearly struggling and in need of psychological, social, and professional support—support that was currently lacking.

In this initial phase, we also endeavoured to develop a co-counselling model, wherein we enlisted the assistance of 20 successful career nurses to provide help and support (mainly through telephone support and counselling) to their struggling colleagues identified in the study. We deemed this strategy appropriate, given the special bonds among nurses related to care and comradeship, as highlighted for example, by Harris and colleagues [

26].

4. Stresses faced by nurses, and consequences of stress:

4.1. Worsening nurse-patient ratios, and financial support for nurses and nursing

Nurses in the UK, as elsewhere, are likely to have commitment to upholding all six of the 6C Values, in the face of the challenging and demanding nature of their profession. This commitment becomes even more critical when their professional integrity is compromised by inadequate compensation. In the United Kingdom due to government policies, nursing salaries had progressively diminished by more than 10% in real terms over a ten-year period by the year 2021 [

27]. Furthermore, a steady reduction in funding for the UK National Health Service (NHS), coupled with government failure to adequately fund or support professional education for nurses in colleges and universities, resulted in a systematic decline in nurse-to-patient ratios when compared to the previous decade [

28].

By 2018, a larger number of nurses, primarily under the age of 50, were leaving the profession in England than in any previous year. This situation seemed to manifest a concerning ‘downward spiral’: as nurse-to-patient ratios worsened and the challenges facing the nursing profession became increasingly stressful, prompting a growing exodus of nurses [

5,

24,

25,

28,

29].

4.2. Psychosocial stress and resilience

Nurses face a multitude of challenges in their demanding roles, which can sometimes lead to psychological distress, burnout, and even thoughts and behaviors related to suicide. These challenges have been observed across various cultures and different healthcare delivery models [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]

From the insights gained through our case studies [

8] and epidemiological data, it becomes evident that despite the lack of adequate material rewards, many nurses are driven to persevere by their unwavering dedication to their demanding profession. This dedication, often described as being “faithful and compassionate,” motivates nurses to persist in the face of high stress. Personal religious faith and deeply held values often empower nurses to continue their dedicated service, even when financial rewards are insufficient [

35,

36]. In this model, nurses establish “a culture of ethical practice delivery” where the importance of material rewards is secondary to their moral commitment to patient care [

37].

4.3. Burnout

Research conducted in the United States before the 2020 COVID pandemic revealed the detrimental consequences of inadequate nurse-patient ratios, in terms of hospital care. This situation often triggers a negative cycle, with overburdened nurses caring for an increasing number of patients, hindering their ability to effectively utilize professional skills. This can lead to disillusionment among nurses, increased levels of anxiety and depression, burnout, and ultimately, a departure from the nursing profession [

38,

39,

40].

Subsequent research conducted in the United Kingdom corroborated these findings, demonstrating that as in the United States, poor nurse-patient ratios are associated with elevated rates of patient morbidity (newly acquired illnesses during hospitalization) and mortality (deaths resulting from substandard care or incomplete clinical tasks) [

41,

42,

43,

44].

The impact of chronic shift-work on normal biological rhythms may impact negatively on both physical and mental health. For example, completed suicide in nurses shows a ‘U’ shaped curve, with younger nurses more likely to choose this drastic form of exit; but older nurses, in the years following their exit from the profession also have higher rates of self-killing [

30]. What is clear is the dropout from the nursing profession is high in the first two years after graduation, and that stress factors which impact mental health adjustment have an influential role [

45]. Rather than “soldiering on” in the face of what seems like an increasingly stressful career, significant numbers of nurses leave the profession in their early years of nursing work, perhaps with some guilt and regret about failing to cope with a professional role to which they were emotionally attached [

46,

47,

48].

4.4. Work-Life-Balance stressors

Many career nurses encounter challenges in maintaining a healthy Work-Life Balance (WLB). These challenges arise from the demands of their profession, such as working extended shifts and night duties [

49,

50], which can put a strain on their social and family life. To account for this potential impact we incorporated a measure of WLB stress into our dataset. This is because it is conceivable that WLB stress could interact with or intensify the stress experienced in their nursing roles. The specific WLB measure we selected is the one developed by Hayman [

51], which is detailed below.

4.5. Burnout and its professional and mental health sequels

Christina Maslach is recognized as the trailblazer in the study and measurement of occupational “burnout” [

52]. Her research laid the foundation for the development of the MBI scale, which has become a widely employed tool in occupational psychology research [

53,

54]. The 20-item MBI scale assesses the susceptibility of professionals in demanding roles, such as nurses, to experience various symptoms, including exhaustion, disillusionment with their roles, a desire to leave their profession, increased illness, depersonalization, and the mechanical execution of routine tasks. The MBI has three subscales: “Emotional exhaustion” (e.g., “I feel emotionally drained from my work”), “Depersonalization” (e.g., “I don’t really care what happens to some patients”), and “Personal accomplishment” (e.g., “I deal effectively with the problems of my patients”).

In the studies reviewed by Dall’Ora et al. in 2020 [

55], the relationships between stress, incipient burnout, and poor professional performance were somewhat complex. Many nurses managed to avoid burnout despite facing multiple stressors, potentially due to their high levels of psychological hardiness [

56,

57]. Thus Munnangi and colleagues [

58] identified only “moderate” levels of burnout stress and symptoms in ER nurses. This suggests that, in challenging and demanding roles, those who are better equipped to handle the stress tend to adapt successfully, with the notion that “the best survive.”

The current study delves into the possibility that a group of relatively senior nurses have largely managed to withstand the many stresses and extra demands of nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic without experiencing burnout. We note in this context that in studies of nurses and individuals involved in caregiving, personality assessments have consistently shown that higher scores on the Extroversion dimension of the OCEAN (Big 5) personality model (discussed in detail below), and lower scores on Neuroticism are the most significant factors in predicting reduced levels of burnout potential as measured by the Maslach scales [

52,

53,

54]. This pattern has also been observed in research conducted by Bakker, Adrianssens and Törnroos and colleagues [

59,

60,

61].

4.6. PTSD as a possible outcome for critical care nurses

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex, often debilitating, disorder that has far-reaching effects, including anxiety, depression, burnout, and compassion fatigue. Working as a critical care unit nurse can be physically and emotionally demanding. Critical care nurses are at increased risk of developing PTSD compared with general care nurses. Employers are also affected due to increased rates of attrition, absenteeism, and general decreased quality in patient care. There is conflicting evidence related to which factors contribute to PTSD but increased resilience holds the most promise for preventing PTSD and its detrimental effects on critical care nurses. (Salmon & Morehead, 2019, p. 515) [

62]

The measurement of PTSD, and its link to problems faced by nurses experiencing COVID-19 related stressors remains a challenge for nursing research [

63,

64].

4.7. Resilience, stress, mental health and coping in nurses

The field of psychological resilience in nurses has yielded significant literature, indicating that some nurses possess unique strengths enabling them to effectively cope with the stresses inherent in their profession, allowing them to navigate professional challenges successfully [

65]. The ‘resilient nurse,’ as assessed through the ‘Big Five’ personality test, typically exhibits emotional stability, extroversion, and strong communication skills [

61,

66,

67,

68]. Researchers studying the careers of healthcare professionals have conceptualized this notion of resilience in various ways. It has been described as “Sense of Personal Autonomy” [

69], as “Hardiness” [

57,

68,

70,

71], and also as a “positive psychology self-enhancement strategy” [

72].

While the Big Five personality dimensions (OCEAN) have a biological basis within an individual’s inherent personality, research suggests that these traits can also be cultivated and coached to improve job performance, stress resilience, and personal satisfaction [

67]. Furthermore, indicators of a hardy personality, such as self-concept and self-esteem, can be bolstered, even in cases where early developmental factors may have hindered self-esteem and self-actualization [

73].

Healthcare professionals including nurses, who exhibit resilience may possess ego-strength that enables them to effectively withstand stress and prevent the emergence of conditions such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in challenging situations [

11,

74]. Nonetheless, it’s essential to recognize that even the most resilient individuals have limits to their endurance. For instance, Bartone et al. [

71], while developing measures of hardiness, noted that a majority of soldiers, although not all, would develop acute PTSD after three months of continuous combat. Similarly, nurses on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic may encounter stressors that lead to the manifestation of PTSD symptoms [

63,

75].

In the two initial phases of our study, validated measures of depression and of self=esteem [

73] have used evaluated both the nurses’ adjustment, and their potential to sustain a positive emotional state when confronted with stress.

4.8. Self-Actualization - humanistic psychology and challenges to the nursing vocation

Our underlying assumption is that in most social systems, all individuals will naturally strive to enhance their personal fulfilment and well-being by contributing to the welfare of others [

76,

77]. As articulated by Bhaskar [

21], this perspective aligns with the concept of “ubuntu” prevalent in some Southern African languages, which roughly translates into “I am, because you are” (p. 113). This viewpoint finds resonance with Abraham Maslow’s theories [

78,

79,

80,

81] regarding human nature and self-realization, informing our approach to comprehending and organizing human activities within the realms of social, nursing and medical professions as a manifestation of ‘public service’ [

82,

83].

We have, each of us, an essential biologically based inner nature, which is to some degree “natural,” intrinsic, given, and, in a certain limited sense, unchangeable, or, at least, unchanging … Each person’s inner nature is in part unique to himself and in part species-wide… This inner nature seems not to be intrinsically or primarily or necessarily evil. The basic needs (for life, for safety and security, for belongingness and affection, for respect and self-respect, and for self-actualization), the basic human emotions and the basic human capacities are on their face, either neutral, pre-moral or positively good. (Maslow, 1964, p. 100) [

78]

Nurses, in particular, may find valuable insights from humanistic and positive psychology, focusing on the cultivation of both ‘emotional intelligence’ and ‘mindfulness’ [

84,

85]. In pursuit of these ideals, akin to the principles espoused by Maslow for achieving self-actualization, our follow-up study on nurses incorporates three metrics aimed at capturing the essence of a well-adjusted, self-actualized individual—someone who is honing their talents and nurturing their “inner goodness” to the fullest extent

The first of these measures is the Self-Actualization assessment developed by Jones & Crandall [

86], drawing from concepts rooted in Maslow’s hierarchical framework of personal development, stress management, and fulfilment (e.g., the item “I respect and assist my colleagues”). The second measure, conducted exclusively during Phase 2 in 2020-2023 is Neff’s [

87,

88,

89] “Self-compassion Scale” (e.g., exemplified by the item “I am compassionate to myself when faced with stress”). The third measure is Lui & Fernando’s well-being scale [

90] which gauges personal fulfilment, a discerning understanding of one’s strengths and limitations, and contentment and happiness in various roles (e.g., of item “I find joy in life,” assessed on a scale from ‘very little’ to ‘most of the time’). Validation studies for these scales indicate that higher scores signify emotional maturity, effective role fulfilment, realistic self-assessment, and satisfaction in achieving personal objectives.

5. Recapitulation of the study’s first phase: measurement, sampling and findings

5.1. Interviewing and study design

Respondents were gathered using the snowball sampling technique [

91] for a study involving nurses who were invited to assess personal and professional challenges by responding to standardized questionnaires. They were also asked about their willingness to participate in the second phase of the survey. In the snowball sampling approach initial respondents, known to the researchers were asked to suggest individuals similar to themselves who might be interested in completing the measures for a study focused on “personal adjustment to the nursing role.” This research was conducted entirely outside of clinical or hospital settings.

Out of the 192 nurses who participated in Phase 1 in 2018, 187 agreed to take part in a follow-up study in 2020 to 2023. Among those 192 who initially agreed to participate, 25 experienced and well-qualified nurses were asked to act as co-counselling professional support volunteers, and 20 of them accepted this role.

The average age of the participants in 2018 was 36.5 years, ranging from 24 to 55 years. All participants held professional nursing qualifications and were employed full-time in National Health Service hospitals. Forty percent of them held positions of relative seniority, beyond that of a staff nurse. Our sampling method led us to contact women who were actively engaged in their nursing roles, and all were permanent or long-term residents of the UK. It’s important to note that the snowball method introduced a bias, as we were studying women who often knew each other, were often at similar career stages, and likely shared some common interests and values.

The initial interviews were completed by June 2018, before the onset of the first COVID-19 pandemic crisis. These interviews, primarily conducted via telephone and the internet, took place outside of clinical settings, and no data regarding the participants’ actual clinical roles or the type and location of hospitals were recorded.

5.2. Ideas explored in the study’s first phase: instruments and questionnaires

In the initial phase, participants completed a questionnaire that covered various aspects of their work history, motivations for choosing a career in nursing, and their considerations regarding leaving the nursing profession. Subsequently, respondents were asked to complete a six-item scale designed to gauge their alignment with the 6C Values of nursing. It’s important to note that this instrument was designed to encourage a positive endorsement of the core nursing values, as we aimed to emphasize the ethical and prominent nature of these values. Our primary focus was to assess the extent to which the nurse respondents felt less than completely confident in applying these values.

Additionally, we included several other measures in our study, including:

Maslach’s Burnout Inventory, a widely used tool in previous research on nurses’ career patterns and morale [

52,

53,

54].

The Short Hardiness Inventory developed by Bartone and colleagues [

71], which aims to explain why certain individuals, such as those in stressful conditions like military combat, emerge without experiencing mental health trauma. Bartone et al. had found found that individuals with high hardiness scores demonstrated a strong sense of life and work commitment, greater perceived control of negative factors in their lives, and a willingness to embrace life’s challenges.

The Big 5 (OCEAN) Personality Inventory, a standard personality assessment measure [

92], and widely accepted for its validity and reliability as established in numerous prior studies [

93]. Three of these five ‘personality have emerged as predictors of relevant outcome variables in the present study: E:

Extroversion (outgoing, energetic, strong and usually positive emotional reactions, sociable, seeking social stimulus in the company of others, socially active and attention-seeking individuals

versus those at the other extreme, described as reserved, shy, withdrawn, self-absorbed, avoiding social interactions; A:

Agreeableness (being straightforward, trusting, altruistic, compliant to the needs and wishes of others, modest, co-operative rather than competitive, not inclined to argue or disagree

versus the polar opposite of these traits, in persons having low scores on this dimension, as rather disagreeable persons.; N:

Neuroticism-Stability (secure and confident individuals who are stable, calm and unworried

versus individuals who are nervous, often worried, anxious and depressed.

A comprehensive analysis of 163 studies that investigated the relationship between OCEAN (Big 5) personality scores and “job satisfaction,” [

67] had revealed that the personality traits of Extroversion (E), Emotional Stability (N), Agreeableness (N) played the most significant roles in defining successful individuals in the context of job satisfaction, particularly in the field of human relationships and people management. In the final analysis of data the three personality profiles were simplified (in order to reduce the number of variables) into a single measure, identifying individuals scoring above the fiftieth percentile on all of the dimensions of Extroversion, Stability (versus Neuroticism) and Agreeableness.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression (CES-D) questionnaire, developed by Radloff in 1977 [

94], is a widely recognized and thoroughly validated 20-item assessment tool designed to identify classical signs of depression. A score of 16 or higher suggests a strong likelihood that an individual is experiencing depression, warranting further investigation and potential treatment [

95].

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) has surprisingly received limited attention in the context of profiling nurses as a professional group [

96]. But one relevant study using the Rosenberg Scale [

97], which demonstrated that lower levels of self-esteem predicted attrition among trainee American nurses. The RSES is a widely used, valid, and reliable measure of self-esteem as a personal trait that is socially constructed through socialization and social interactions, ultimately forming a strong foundation for inner strength and self-confidence in coping with subsequent life stresses [

73]. This body of evidence underscores that, by young adulthood, self-esteem becomes a fundamental aspect of one’s personality and is often resistant to modification. In the tables provided below, a higher RSES score indicates a more favourable level of self-esteem.

Hayman’s assessment of stress associated with Work-Life Balance (WLB) challenges measures a type of stress arising from the disparity between one’s professional commitments and their family and personal pursuits outside of paid work. We selected Hayman’s scale [

51,

98] due to its robust evidence of discriminant validity, and the concept’s relevance as an appropriate tool for use by human service professionals [

99]. This instrument has three distinct sub-scales. However, because the third sub-scale assesses a different dimension of work-life balance, we consolidated the first two sub-scales into a single composite measure, which has demonstrated a high level of internal consistency. A higher score on this measure reflects a greater degree of stress attributed to work-life imbalance, a phenomenon observed not only in nurses but also in other professional groups [

100,

101].

5.3. The initial model explored in the 2018 study

Initial exploration of concept revolved around the idea that a strong commitment to Nursing Values would exhibit a positive correlation with personal strengths, such as high self-esteem, specific personality traits, and a resilient personality profile. Professional value commitment was expected to exhibit negative correlations with psychological discomfort, social stressors (e.g., work-life balance issues), and work-related stress, as indicated by the potential for burnout. Additionally, a key question was whether reduced commitment to nursing values could predict an intention to leave the nursing profession and whether this prediction’s significance would persist when considering other variables in the study. Our secondary objective was to use heuristic and intuitive statistical analyses to identify distinct subgroups within the cohort of nurses, distinguishing those with unique strengths and those who were susceptible to various forms of stress.

The Nursing Values Questionnaire (NVQ) [

8] was designed to elicit positive responses indicating agreement with six types of value orientation guiding the best kind of nursing practice. Higher NVQ scores were significantly associated with having a hardy personality, good self-esteem, occupying higher-ranking positions, lacking any intention to leave the nursing profession, demonstrating agreeable personality traits, and being free from symptoms of depression or neuroticism, while also displaying lower scores on burnout sub-scales.

Intention to depart from the nursing profession (temporarily or permanently) within a year was established as a standard measure for correlation analysis. Intention to leave was significantly predicted (P<.01) by being younger, holding a lower job rank, experiencing higher levels of depression and neuroticism, having lower self-esteem, lacking a Hardy Personality, obtaining higher scores on the Burnout Scales, encountering stress related to Work-Life Balance, being less Extroverted and Agreeable, and demonstrating a somewhat weaker attachment to fundamental Nursing Values.

An exploratory factor analysis using Principal Components identified groups of variables, allowing us (through the SPSS program) to calculate factor scores for each participant in both the 2018 study, and for the repeated or additional measures in the 2020-23 follow-up. For each data sweep we utilized factor scores from three major components, which collectively accounted for more than 50% of the total variance in the measures used. These factor scores were subjected to numerical cluster analysis, employing each individual’s factor score to categorize nurses into groups, with the objective of maximizing the averaged numerical distance between members of different groups. As a result of this heuristic analysis, we identified four distinct clusters of individuals in the 2018 study [

Table 1.] This cluster analysis yielded four distinct categories of nurses:

Group A (N = 79) - “The Soldiers”: This group displayed moderate scores on most metrics, exhibited some signs of burnout, had fewer intentions to leave the nursing profession, but experienced higher levels of work-life stress. They also scored somewhat lower on agreeableness and the nursing values scale.

Group B (N = 54) - “Cheerful Professionals”: These nurses held higher job ranks, were more extroverted, displayed greater agreeableness, possessed better self-esteem, and reported few signs of depression. They atypically planned to leave nursing, and had moderate to low scores on neuroticism and depression. Additionally, they showed a good level of self-esteem but with a moderate hardy personality score, along with a somewhat stronger attachment to core nursing values.

Group C (N = 20) - “Highly Stressed, Potential Leavers”: This group experienced high levels of depression and neuroticism, had lower self-esteem, were less extroverted, and exhibited low “hardy personality” profiles. They also reported work-life stress and displayed a somewhat lesser attachment to core nursing values, linked to an inclination to leave the profession.

Group D (N = 39) - “High Achievers, Strong and Stable”: Nurses in this group held higher job ranks, were more extroverted, and scored lower on measures of neuroticism and depression. They also displayed higher scores on hardiness and self-esteem, experienced less work-life stress, had lower levels of burnout, and demonstrated a strong profile of nursing values.

Table 1.

Cluster analysis of 192 nurses, using factor scores from principal components analysis.

Table 1.

Cluster analysis of 192 nurses, using factor scores from principal components analysis.

| Variable |

A : “The Soldiers” (79) |

B: “Cheerful Professionals” (54) |

C: “Highly Stressed, Potential Leavers” (20) |

D: “High Achievers, Strong & Stable” (39) |

Value & significance of Chi2 of variable across 4 categories |

| Job rank high |

13% |

31% |

6% |

49% |

36.71 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Considers leaving nursing? |

15% |

9% |

80% |

3% |

65.15 (3 df) p<.0000 |

| Neuroticism hi quartile |

25% |

26% |

37% |

12% |

86.41 (6 df)

P<.0000 |

| Extroversion hi quartile |

15% |

31% |

6% |

48% |

46.23 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Agreeableness hi quartile |

27% |

32% |

10% |

31% |

20.86 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Hardiness hi quartile |

23% |

30% |

2% |

44% |

38.37 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Depression hi quartile |

29% |

25% |

30% |

17% |

51.02 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Self-Esteem hi quartile |

24% |

33% |

4% |

39% |

64.35 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Burnout hi quartile |

32% |

25% |

35% |

8% |

94.47 (6 df) p<.0000 |

| Work-Life Stress hi quartile |

30% |

25% |

30% |

15% |

50.53 (6 df)P<.0000 |

| Nursing Values hi quartile |

24% |

30% |

10% |

36% |

41.32 (6 df) p<.0000 |

6. Phase Two: Research questions for the 2020-2023 follow-up study

6.1. Initial questions

In our follow-up interviews with nurses from our research cohort, conducted between 24 and 36 months after initial interviews, we aimed to investigate several key research questions:

Firstly, we sought to assess the reliability of measures completed at two different time points by examining correlations between them. We aimed to determine whether the nurses’ “intention to leave nursing” at the initial interview point predicted actual behavior. Additionally, we explored which variables, measured at Time 1, might help identify nurses who had left the profession by Time 2. We consider the implications of these findings for interventions aimed at supporting nurses contemplating leaving their profession.

Secondly, we delved into the validity and significance of the 2018 categorization of “four types of nurses” in predicting those who left and those who stayed in the face of potential stress from COVID-related nursing challenges. We also investigated whether component and cluster analysis could identify similar Types of Nurses in 2020-23 compared to those from the 2018 cohort. We wished to assess whether this typology remained consistent after further statistical analysis, including new measures of positive adjustment and self-actualization. We also wished to examine whether nurses in our cohort exhibited signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following the waves of COVID-19 in the UK.

Thirdly, we wished to examine the significant correlations between three new measures completed in the 2020 to 2023 follow-up interviews, estimating various aspects of self-actualization, and other scales completed in both 2018 and in the follow-up work.

Our fourth objective was to try and identify a group of nurses whose professional careers aligned with Maslow’s concept of self-actualization, extending beyond the ego-enhancing aspects of professional success. We aimed to explore whether these nurses progressed towards a psychological state characterized by enhanced self-awareness and mindfulness, ultimately leading to self-transcendence [

81,

102].

6.2. Locating nurses in the follow-up study

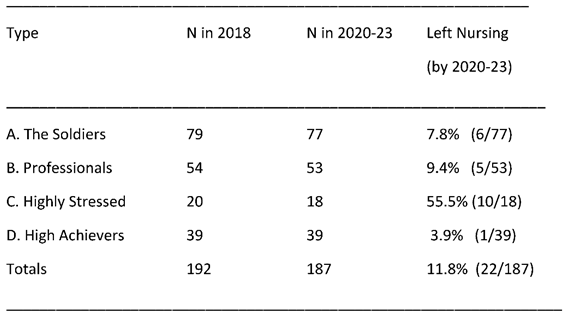

In the initial phase, we reached out to nurses located in Northern England through in-person interactions (‘snowball sampling’ in which initial contacts referred nurse colleagues who might be interested in the research study). For the follow-up spanning from 2020 to 2023 the Nurses in the original study were initially contacted via phone or email, and completed questionnaires online. Out of the original cohort of 192 nurses five had previously expressed their preference not to be contacted again. Among the remaining 187 nurses we contacted, only two declined to participate in the follow-up interview. Consequently, the final count of nurses who completed the comprehensive follow-up interview stood at 185, which included 22 nurses who had recently exited the profession, (temporarily or permanently), as outlined in

Table 2.

7. Indications of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the 2020 data sweep?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) manifests itself through enduring and often frightening symptoms, including anxiety, depression, disrupted sleep patterns, hypervigilance, and flashbacks. These manifestations arise from exposure to profound trauma, which can be physical, psychological, or a combination of both [

74,

103]. This process involves intricate, albeit typically temporary, neurobiological alterations [

104,

105] A growing concern revolves around healthcare professionals, especially nurses, who, having provided care during the COVID-19 pandemic, may face an increased risk of developing PTSD and related syndromes [

63,

106,

107,

108,

109].

In a longitudinal study spanning nine months in 2020, which included several hundred nurses, it was observed that working directly with COVID-19 patients for extended periods with limited breaks or rest during the health crisis often led to the development of symptoms resembling those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

110]. In light of these findings, advocates for nursing professionals emphasize the importance of implementing strategies to mitigate high levels of stress, PTSD, and burnout. They propose that nurses should be regularly rotated away from direct patient care duties and provided with additional mental health support [

63,

111]. Unfortunately, in countries like Britain where nurses are already in short supply with inadequate nurse-patient ratios, providing such stress relief measures is extremely challenging because of underfunding of health services [

112].

What is particularly noteworthy in the research on nurses enduring prolonged, high-stress situations, such as COVID-19 nursing, is that more than two-thirds apparently without exhibiting symptoms of mental illness, trauma, depression, anxiety, or PTSD [

63]. The diagnosed rates of PTSD in nurses across various studies included in that review varied from 8 to 30 percent. This psychological resilience and the capacity to withstand these challenges certainly warrants further investigation and study.

Although reliable and valid measures of PTSD, such as the PTSD-8 [

103] have been developed, these assessments are typically validated against specific, one-time traumatic events like a car crash, an environmental disaster, or a violent sexual assault. Attempting to address this we modified and rephrased the 8-item PTSD-8 scale into a

PTSD-N for Nurses scale, incorporating specific questions about post-traumatic stress related to challenges in nursing (e.g., sudden and unexpected death of a patient). Surprisingly, in our study of 185 nurses, 102 reported no enduring memory of a “traumatizing” event which had affected their mood or mental state in the past month. Instead, they viewed the death and suffering of patients as part of their everyday nursing role, coping with these challenges in a professional yet compassionate manner, and not experiencing personal trauma, as per their personal accounts. Twenty seven nurses had been infected with COVID-19, and ten of these women took extended leave following the infection. None of the nurses recorded their personal illness from COVID as a cause of PTSD-like symptoms.

The PTSD-N scale begins with the question: “The following are some of the ways in which nurses may act after experiencing or witnessing an event or series of events, such as unexpected or prolonged severe pain in a patient; distress or death of a patient or patients and/or their relatives; the expression of aggression against you …Exhaustion with no breaks …Chronic physical pain from nursing … Any personal illness arising from your care of patients ...And other factors If any of these did occur, considering the most recent event(s) of this type, please check your reactions or feelings concerning any such event …

Results indicated the responses: “I have not experienced any such a ‘traumatic’ events’: (23 of 185 nurses, 12.4%); “Such events have occurred in my experience as a nurse, but I do not have any recent ‘post-traumatic’ feelings in the past month, concerning such event(s)” (115 of 185 nurses, 62.2%); “I have experienced such event(s) which were a psychological challenge, with some continuing ‘post-traumatic’ negative feelings (e.g., continued anxiety, depression or sleep problems) in the past month” (47 of 185 nurses (25.4%). On a 4-point scale (“Not at All” to “Most or all of the Time”), a mean score of 3.26 (SD 2.47) for the 185 nurses was calculated, with 119 reporting no PTSD signs, 40 reporting moderate signs, and 26 reporting more marked signs according to the various categories identified by the questionnaire. Of these 40, we followed cut-off points in previous research [

63] to suggest that 16 of the 185 nurses (including those no longer in nursing roles) might present clinical profiles of PTSD. This is a tentative diagnosis based on a measure that has yet to be fully validated and its reliability checked. We did however offer appropriate clinical referrals for distressed individuals.

8. Three ‘Self-Actualizing ‘measures completed in 2020-23

8.1. The Self-Actualization Scale

The Jones & Crandall measure [

86] was specifically designed to directly measure Maslow’s concepts of fulfilling basic needs on the path towards self-actualization and self-transcendence. In the case of two other scales, namely, the Lui-Fernando

Well-Being Scale and the Neff

Self-Compassion Scale, these have been shortened to include only those items that exhibited high factor loadings (>.50) in the original factor analyses. Fuller details of these three scales and their factorial reliability are given in Adam-Bagley et al. (2021) [

9].

8.2. The Self-Compassion Scale

In the analyses by Neff and her team, “high self-compassion” is frequently linked to personality traits such as extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and a lack of neuroticism, as measured by the OCEAN personality indicators [

92,

93]. Neff and Vonk [

113] conclude that individuals with high self-compassion are more likely to experience positive emotions because they embrace themselves “as they are”. Self-compassion also fosters a sense of connection with others and may represent a close approximation of “optimal” or “true” self-esteem.

Attaining elevated levels of self-compassion can also align with what Maslow [

79,

80] defines as “self-actualization” and, ultimately, “self-transcendence.” Neff and Vonk [

113] also observed that achieving a realistic self-appraisal and cultivating self-compassion can be facilitated through mindfulness training, a technique successfully employed in providing psychological support to professionals like nurses, as evidenced by studies conducted by Mealer and colleagues in 2017 [

114] and Stanulewicz et al. in 2019 [

115].

8.5. Personal Well-Being

In 2018, Lui and Fernando [

90] introduced the Well-Being Scale (WBS) as an elaboration of Maslow’s concept of the self-actualizing individual, where “happiness and well-being stem from one’s dedication to serving others” (p. 140). This concept is rooted in the notion of synergy, wherein altruistic actions not only benefit the individual but also bring rewards to others. For us, this represents the paramount guiding principle in the practice of nursing. It encompasses the responsibility of individuals who possess a lasting and unwavering sense of well-being, attained through self-awareness, and their commitment to serving others. This revised 16-item scale has factorial validity, and includes items such as “I can solve the problems I face”, “I have the potential to reach my goals”, “I have a satisfying spiritual life” [

90]

9. Further classification of nurses

9.1. Initial results

It’s important to note that the further data collection (conducted between 2020 and 2023) also involved nurses who had left the nursing profession or were taking ‘professional breaks’), and who were not interviewed in 2020 [

9].

Table 3 compares the mean values and correlations of the measurements obtained during the first and the last interview sets, in 2018 and subsequently between 2020 and 2023. Repeated measures exhibited statistical significance over time, suggesting a degree of reliability for the metrics, including Nursing Values, Hardiness, Work-Life Balance Stress, and Self-Esteem. However, it should be noted that the manifestation of Depression was less persistent over time, indicating both recovery from depression in some, and its onset in others.

The OCEAN personality scales [

92,

93] were not administered during the 2020-2023 data collection. Instead, the three primary profiles (Extroversion, Stability, and Agreeableness) from the 2018 data collection were fitted to a binary classification, describing a group that could be characterized as “Outgoing, Emotionally Stable & Agreeable” based on scores above the mean in the relevant direction, on each of the three personality dimensions. This binary categorization was incorporated into the taxonomic analysis of nurses who responded during the 2020-2023 follow-up, with 50 nurses being classified as having higher scores (above the mean for

all of the three personality dimensions).

Table 3.

Means and correlations of nurses’ adjustment and coping Scales, Phase 1 (2018) compared with Phase 2 (2020-23).

Table 3.

Means and correlations of nurses’ adjustment and coping Scales, Phase 1 (2018) compared with Phase 2 (2020-23).

| |

2018 N=192

Mean (SD) |

2020-23 N=185

Mean (SD) |

Correlations

2018 to 2020-2023 |

| NVS (Nursing Values) |

12.64 (3.67) |

14.04 (4.18) |

.45 |

| Hardiness |

33.85 (8.59) |

34.76 (7.93) |

.51 |

| Self-Esteem (Rosenberg RSES) |

28.89 (5.55) |

31.71 (5.51) |

.42 |

| Burnout |

5.63 (1.79) |

6.82 (2.73) |

.38 |

| WLB Stress |

12.54 (4.21) |

16..26 (5.23) |

.40 |

| Self Actualization |

Not completed |

31.55 (6.28)

|

- |

| Self Compassion |

Not completed |

30.37 (6.39) |

- |

| Personal Well-Being |

Not completed |

61.26 (8.30) |

- |

| CESD Depression |

12.50 (9.92) |

10.25 (7.62) |

.26 |

| PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress |

Not completed |

3.26 (2.47) (16/185 above clinical cut-off) |

- |

Personality:

Agreeable, Extroverted & Emotionally Stable |

1.0 (normalised, Gaussian curve) |

Not completed |

- |

| COVID-19 Contact Nursing |

Not relevant |

86.4% |

- |

9.2. Correlation, component and cluster analysis to identify ‘types of nurses’

To achieve a clustering of individuals, as opposed to grouping variables, we followed a procedure similar to that used for the analysis of Sweep 1 data, employing k-means cluster analysis with the SPSS program [

8]. The analysis of the 2020-23 data yielded groups which were somewhat less clear cut than in 2018. Nonetheless, a 3-group solution, chosen to maximize statistical distance between three clusters does offer a certain theoretical clarity. But it’s important to note that 22 individuals were identified as outliers and could not be effectively incorporated into any of the three groups. While a 4- or 5-group solution could accommodate most of these individuals, it came at the cost of clarity in defining the other groups. Therefore, the 3-group solution was retained due to its heuristic value.

The largest group, denoted as Group A (n=62), is labelled “Actualizing Professionals.” This group exhibits positive personality profiles, a robust Hardy personality, high scores in well-being scores, self-compassion, and movement towards self-actualization. Notably, this group comprises a core segment of both the 2018 “Strong Professionals” from Group B, and “High Achievers” from Group D.

The next cluster Group B (n=56), we have referred to as “Strong Professionals,” a group which comprises the most senior individuals who are committed to Nursing Values. They exhibit strong self-esteem and self-compassion. Notably, this group includes a core subset of individuals who were part of the 2018 “Strong Professionals” group.

The third group, Group C (n=45), is labelled “Highly Stressed Nurses.” This group consists of nurses who are grappling with burnout and are contemplating leaving the nursing profession. They also experience significant stress related to work-life balance, primarily centered around childcare responsibilities. It’s worth noting that this group encompasses all the nurses who were provisionally categorized as falling into the PTSD clinical category. Within this group, we find both “Soldiers” and “Highly Stressed” nurses from the previous grouping.

There is a certain consistency in the clusters over a five-year period, suggesting potential reliability and validity in the clustering process. Initially, some senior nurses were enlisted as telephone counsellors for their struggling colleagues, with 15 of them fulfilling this role throughout the five-year span. Due to ethical considerations, specific details of these conversations were not sought. However, we know that many of these “counselling discussions” often resulted in the recommendation for highly stressed colleagues to consider taking a career break.

One notable finding was the less favourable outcomes for the “Soldiers” identified in Phase One. Contrary to initial expectation, the majority of these nurses did not transition into resilient, long-term career nurses. Instead, they either became “highly stressed” nurses or exhibited inconsistent patterns of adjustment, making it challenging to categorize them into clearly defined groups in Phase Three of our research.

Table 4.

Principal components analysis of measures completed by 185 nurses in 2020-2023 interviews.

Table 4.

Principal components analysis of measures completed by 185 nurses in 2020-2023 interviews.

| |

Factor I (24% of variance) |

Factor II (18% of variance |

Factor III (8% of variance) |

| Job rank (low to high) |

.38 |

.18 |

-.20 |

| Extroverted+Stable+Agreeable |

.65 |

- .35 |

.02 |

| Hardy Personality |

.63 |

-.56

|

-.18 |

| CESD Depression (lo to high) |

.22 |

-.17 |

.51 |

| Self-esteem (low to high) |

.43 |

-.54

|

-.04 |

| Burnout Scales (high to low) |

.17 |

-.08 |

- .55

|

| Work-Life Balance stress (low to high) |

.20 |

.01 |

- .61

|

| Intention to Leave Nursing |

-.23 |

.01 |

- .51

|

| Nursing Values Questionnaire |

.38 |

-.54

|

- .19 |

| PTSD-N Measure (low to high stress) |

.00 |

-.00 |

- .33 |

| Self-Compassion |

.61 |

-.39

|

- .18 |

| Personal Well-Being |

.67 |

-.55

|

- .13 |

| Self-Actualization |

.58 |

-.30 |

-.03 |

Table 5.

Typology of nurses from the 2020-23 interviews, combined with the 2018 data.

Table 5.

Typology of nurses from the 2020-23 interviews, combined with the 2018 data.

| |

A “Actualizing Professionals” (n=62) |

B “Strong Professionals” (n=56) |

C “Highly Stressed Nurses”

(n=45) |

Value & Significance of Chi-squared |

| Job rank high |

57.6% |

72.7% |

40.0% |

Chi2 (4df, 144) p<.0002 |

| Plans to leave nursing? |

25.4% |

18.2% |

60.0% |

Chi2 (4df, 144) p<.0002 |

| Personality, high on 3 types (n=23) |

56.5% |

14.5% |

6.6% |

Chi2 (4df, 144)

p<.05 |

| Hardiness, top 25% (n=36) |

63.9% |

27.8% |

10.0% |

Chi2 (4df, 144) p<.0002 |

| Depression, top 25% (n=36) |

18.6% |

18.2% |

50.0% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144)

p<.01 |

| High Self-Esteem, top 25% (n=36) |

13.5% |

36.4% |

26.6% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144), p<.0000 |

| Burnout, top 25% |

6.8% |

20.0% |

70.0% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144) p<.0000 |

| WLB stress, top 25% |

8.5% |

25.4% |

56.6% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144 ) p<.0000 |

| Nursing Values, top 25% |

25.4% |

27.2% |

20.0% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144) p=.730, not significant |

| Well-Being scale, top 25% |

32.2%% |

21.8% |

16.6% |

Chi2 (4df, 144) p.<01=.746 |

| Self-Compassion scale, top 25% |

32.2% |

27.2% |

6.7% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144) <.01 |

| Self-Actualization scale, top 25% |

35.5% |

20.0% |

13.3% |

Chi2 (4 df, 144) p<.003 |

| PTSD-N ‘clinical’ group |

0.0% |

0.0% |

43.3% |

Chi2 (3df, 144) p<.0000 |

(A) ‘Soldiers’ (in 2018)

(B) ‘Professionals’ (in 2018)

C) ‘Stressed’ in (2018)

(D) ‘High Achievers, in (2018) |

A: 0.0%

B: 40.3%

C: 8.1%

D: 56.4%

|

8.9%

60.7%

0.0%

25.0%

|

40.0%

0.0%

20.8%

0.0% |

|

10. Discussion

10.1. Perspective from humanist psychology

This research is grounded in the perspective of humanist psychology [

76,

77] in which each “subject” in a study is a unique human being, and is best framed in research terms as either unique, or as a member of a unique or special group within a broader social matrix, such as a hospital or other organization [

8]. For this reason we have chosen to move from a purely psychometric study to one which classifies individuals according to their ‘unique’ groupings, which we have conceived in terms of Abraham Maslow’s perspective [

77,

83].We follow Joseph (2019) [

116] in adopting this humanistic perspective, asserting that the concept of the “synergist person” within Maslow’s model can effectively confront and conquer challenges that may potentially lead (for example) to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in some individuals.

Certain personality styles play a vital role in aiding individuals to transcend these challenges, contributing to personal and interpersonal growth as individuals such as nurses and other health professionals progress towards

self-actualization. A core of nurses in our study appear to be making significant strides in this regard through “resilience training”, Siebert [

117] extends this concept by exploring its relevance among frontline soldiers and subsequently applying it to a broader spectrum of individuals, including managers and professionals from various fields:

Central to the development of a synergistic personality is the integration of paradoxical personality traits. Such persons are comfortable with and value their inner counter-balanced dimensions. They appreciate the benefits derived from being able to engage in pessimistic optimism, cooperative non-conformity, selfish altruism, extroverted introversion, playful seriousness, and more. (p. 12) [

117]

In Siebert’s framework, individuals, including nurses, with “survivor personalities” are those who exhibit the following characteristics: (a) they have successfully navigated significant crises; (b) they have overcome threatening situations through their personal efforts; (c) they have emerged with previously undiscovered strengths and capabilities; and (d) upon reflection, they find value in the challenging ordeals they’ve endured. While inherent resilience is certainly valuable, Siebert suggests that many professionals can also be trained and supported to discover resilience when confronted with stress.

Several crucial characteristics identified in 2018 have significant predictive power for how the 2020-23 cohort in the present study have survived the trial of COVID-19 nursing, including the personality types of Extroversion, Emotional Stability, and Agreeableness, along with Hardiness, and associated psychological variables linked to stable individuals seeking to achieve the best in their personal and professional lives. Strong value commitment to nursing, lack of depression and good self-esteem also help, as does the absence of factors undermining good work-life balance.

Nurses who do not possess these positive traits often encounter difficulties in finding satisfaction in their profession, particularly when faced with crises such as the demanding circumstances of nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is crucial to recognize the challenges that these nurses face, and efforts should be made to identify roles for them within hospital or medical settings that reduce stress. Furthermore, nurse training and ongoing education programs should prioritize strategies for effectively managing the unique stressors inherent in the nursing profession, as these stressors can compromise the values that nurses are, or should be, committed to [

13,

111]

We are also concerned about the elevated occurrence of PTSD symptoms among some of the highly stressed nurses in our study. Future follow-up research may provide insights into the experiences and resilience of nurses who faced the overwhelming crisis in the English hospital system during the Fall and Winter of 2020 to 2021 [

5,

6,

106,

107]. It’s important to note that the acute stress resulting from the demands of COVID-19 nursing is not limited to the United Kingdom but is a global issue (Ciu et al., 2020; [

110,

118,

119]. Certainly, studies examining experiences of nurses who have battled the challenges of COVID-19 nursing in various parts of the world are highly valuable.

10.2. Nursing as the lead profession in COVID care

Hospital nurses are a highly dedicated and motivated group, and many draw on both psychological strengths, and personal values in finding the highest levels of achievement and non-material reward in their profession. Two of the authors of this paper have had professional nurse training, and we draw on this experience in arguing, as other nurse practitioners and educators do, that nurses are

the leading profession in delivering hospital-based health care. Nurse practitioners and leaders are, as Liaschenko & Peter [

120] argue, the dedicated experts in treatment

and management of health care, calling on a range of diagnostic and technical specialists (e.g., radiologists, surgeons, etc) in delivering that care. The COVID-19 epidemic has show how crucial these nurse managers are in delivering, ordering and managing patient care, leading to advocacy for a radical and permanent reorganisation of health delivery (e.g., Stucky et al., 2020) [

121]. Their overview of COVID-19 care in China, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, Brazil and the USA underscores these arguments: “Despite personal risks, nurses across the globe stepped up to the challenges of upholding and improving the health of the world’s people … offering ways forward in both nursing practice and health policy.” (Zipf et al., 2021, p. 92) [

122]

De Raeve et al. (2021) [

123] in their international survey argue that nurses, more than any other health professional, have had the key role in holding beleaguered health systems together as the frontline soldiers whose energy and dedication have fed into relevant policies, a view which echoes Shaffer et al.’s (2020) [

124] international review, and Anders’ (2020) [

125] discussion of nurses facing America’s COVID-19, who have influenced health policy in important directions, echoes this view.

These reviews and research accounts identify studies which fit well with our own findings. Nursing is a brave and highly skilled profession which may lead the way in health care delivery and reform. Highly valued nurse practitioners are rewarded by their profession and by their dedication to that profession, in the face of many difficulties. In the Critical Realist model [

20,

21], nurses have the potential to

recreate health systems.

10.3. Study Limitations

We haven’t included male nurses in our current research cohort due to limited resources, even though they constitute a somewhat marginalized group within a predominantly female-dominated profession [

126]. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of studying male nurses in our future research.

It is acknowledged that our study is based on a relatively small research population, and may not be representative of all English nurses. The recruitment of informants through personal contact means that the ‘snowball’ method may have collected together a relatively homogenous group of professionals [

127] and this may have influenced statistical outcomes, such as the apparent success in identifying particular groups in the cluster analysis (although this method of sampling may be particularly relevant during and post pandemics – [

128]). Replication is called for, with a larger, randomly chosen group of nursing professionals. Some of the measures we’ve developed, such as the Nursing Values questionnaire, and the PTSD measure for nurses need a fuller review and replication in the light of existing measures for other groups [

129].

Author Contributions

The three authors shared equal responsibility in the conceptualization, conduct of research, and in the writing of this paper.

Funding

This research was not supported by any external funding.

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and received the ethical approval of the National Health Service (England) for research undertaken outside of health settings, with professional, non-clinical subjects (Ref: NHS NW16.37).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved.

Data Availability Statement

Requests will be considered carefully. Supply of data will require separating qualitative findings from the data files.

Conflicts of Interest

The three authors declare no conflict of interest. None of them is professionally concerned with the current delivery of health care, or with nurse education. Two of the authors have been Registered Nurses with professional responsibilities, in the previous century.

References

- ONS (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Related Deaths by Occupation, England and Wales: Deaths Registered Between 9 March and 25 May 2020. London: Office for National Statistics.

- Mitchell, G. (2021). Covid-19: New nurse death figures prompt call for investigation. Nursing Times, 25, January 25th, 2021, Online, Consulted August 5th, 2021.

- Hackett, K. (2021). PPE provision ‘nowhere near enough’ in first wave and staff left at risk, say MPs: Committee urges government to learn lessons and improve management and distribution. Royal College of Nurses: Nursing Standard, February 12th, 2021, Consulted August 6th, 2021.

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, J. (2021). Army deployment in NHS hospitals exposes scale of staffing crisis. Royal College of Nursing: Nursing Management Journal, January 21st, 2021, Online, Consulted August 6th, 2021. 21 January.

- Waddington, E. (2021). Redeployed in emergency care: anxiety and dread in one 12-hour shift. Royal College of Nursing: Nursing Standard, February 10th, 2021, Consulted August 6th, 2021. 10 February.

- Guardian (2021). This is what it’s like to be an intensive care unit nurse right now. The Guardian Online, January 20th, 2021, Consulted January 20th, 2021. 20 January.

- Adam-Bagley, C.; Abubaker, M.; Sawyerr, A. Personality, work-life balance, hardiness, and vocation: A typology of nurses and nursing values in a special sample of English hospital nurses. Adm. Sci. 2018, 84, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Bagley, C.; Sawyerr, A. Abubaker. M.; Shahnaz, A. Resilient nurses coping with COVID care: a longitudinal study of psychology, values, resilience, stress and burnout. J. Hum. Resour. Leadersh. 2021, 5, 88–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, A. An analysis of England’s nursing policy on compassion and the 6 C s: the hidden presence of M. Simone Roach’s model of caring. Nurs. Inq. 2016, 23, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadner, K.D. (1989). Resilience in Nursing: The Relationship of Ego Strength, Social Intimacy, and Resourcefulness to Coping. Austin: University of Austin Press.

- Thomas, C. (2020). Resilient Health and Care: Learning the Lessons of COVID-19 Resilient Health Care in the English NHS. London: Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).

- Watson, J. Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring; University of Colorado Press: Denver, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.; Witt, J.; Duffield, C.; Kalb, G. What do nurses and midwives value about their jobs? Results from a discrete choice experiment. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2015, 20, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehtab, S.; Adib-Hajbaghery, M. The importance of spiritual care in nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies 2014, 3, e22261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, Jo. 2014. NHS England to roll out ‘6Cs’ nursing values to all health service staff. Nursing Times, April 23, Online, consulted August 9th, 2021.

- Spurlock, D. Beyond p < 0.05: Toward a Nightingalean perspective on statistical significance for nurse education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2017, 66, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, M.D. Nursing’s code of ethics, social ethics, and social policy. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2016, 46, S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J., 2004. Caring Science as Sacred Science. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Publishers.

- Archer, M.S. (2011). Morphogenesis: Critical Realism’s explanatory framework. In M. S. Archer (Ed.) Sociological Realism (pp. 66-101). London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. Critical realism and the ontology of persons. J. Crit. Realism 2020, 19, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, P. (2015). The Politics of Childhoods Real and Imagined: Practical Application of Critical Realism and Childhood Studies. London: Routledge.

- Alderson, P. (2021). Critical Realism for Health and Illness Research: A Practical Introduction. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Mulholland, A. (2020). Anne Marie Rafferty: ‘Covid should be circuit breaker for the ills plaguing nursing’. The Guardian Online, October 21, 2020, Consulted October 21, 2020.

- Hackett, K. Quarter of nurses leave the profession due to stress. R. Coll. Nurs. : Nurs. Manag. 2020, 22, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Ryan, M.; Belmont, M. More than a friend: the special bond between nurses. Am. J. Nurs. 1997, 97, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnair, D. (2021). Making the case for a pay rise. Royal College of Nursing, Press Briefing, Consulted December 4, 2021. 4 December.

- RCN (2009–2022). Annual Reports. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- Triggle, N. (2018). NHS Hemorrhaging Nurses, as 33,000 Leave Each Year. British Broadcasting Corporation. Available online: https://www. bbc. co/news/health-42653542, Consulted March 1st, 2018).

- Feskanich, D.; Hastrup, J.L.; Marshall, J.R.; Colditz, G.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Kawachi, I. Stress and suicide in the Nurses’ health study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J., Lok, A., van’t Verlaat, E., Duivenvoorden, H. Bakker, A. &, Smit, B. Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 316–326. [CrossRef]

- Kõlves, K.; De Leo, D. Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: an analysis of the Queensland Suicide Register. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M., Parent-Rocheleau, X.; Mishara, B. Critical review on suicide among nurses. Crisis 2015, 36, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, E.L.; Northrop, L.; Edelstein, B. Stress, social support, and burnout among long-term care nursing staff. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakibinga, P.; Vinje, H.F.; Mittelmark, M. The role of religion in the work lives and coping strategies of Ugandan nurses. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, M. Assessing the incremental validity of spirituality in predicting nurses’ burnout. Arch. Für Relig. /Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2014, 36, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H. Creating a culture of ethical practice in health care delivery systems. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2016, 46, S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, L.; Ryan, C.S.; Thomas, S.; Greenberg, M.; Rolniak, S. Nursing specialty and burnout. Psychology Health & Medicine 2007, 12, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, B.; Barriball, K.L. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: A review of the research literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keneisha, K., Fowler, K.; Eller, M. Newly licensed RNs; and missed care. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 168–175.

- Aiken, L.H. Clarke, S., Sloane, D.,M. Lake, E.; Cheney, T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcome. J. Nurs. Adm. 2008, 38, 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H., Sloane, D.M., Bruyneel, L., Van den Heede, K., Griffiths, P., Busse, R., ...& Sermeus, W. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1824–1830. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P., Ball, J., Drennan, J., James, L., Jones, J., Recio, A., & Simon, M. (2014). The Association Between Patient Safety Outcomes and Nurse/Healthcare Assistant Skill Mix and Staffing Levels. Southampton: Centre for Innovation and Leadership in Health Services.

- Griffiths, P., Ball, J., Murrells, T., Jones, S.; Rafferty, A.-M. Registered nurse, healthcare support worker, medical staffing levels and mortality in English hospital trusts: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e008751. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Shang, L., Galatsch, M., Siegrist, J., Müller, B.H., Hasselhorn, H.M., & NEXT Study Group. Psychosocial work environment and intention to leave the nursing profession: a cross-national prospective study of eight countries. Int. J. Health Serv. 2013, 43, 519–536. [CrossRef]

- Barron, D.; West, E. Leaving nursing: an event-history analysis of nurses’ careers. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courvoisier, D.S.; Cullati, S.; Haller, C.S.; Schmidt, R.E.; Haller, G.; Agoritsas, T.; Perneger, T.V. Validation of a 10-item care-related regret intensity scale (RIS-10) for health care professionals. Med. Care 2013, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, M.M., van Achterberg, T., Schwendimann, R., Zander, B., Matthews, A., Kózka, M., Ball, J.; Schoonhoven, L. Nurses’ intention to leave their profession: a cross sectional observational study in 10 European countries. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 174–184. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, C.G.; Colombo, L.; Ghislieri, C. Determinants of nurses’ job satisfaction: the role of work–family conflict, job demand, emotional charge and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düchting, M. (2015). Improving the Work-Life Balance of Registered Nurses. Norderstedt DE: Grin Verlag.

- Hayman, J.R. Psychometric assessment of an instrument designed to measure work life balance. Res. Pract. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 13, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. (1986).Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. (2006) Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual 5th Edn. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]