1. Introduction

The current socio-cultural panorama focuses on the promotion of policies – both national and local – which encourage the promotion of tourism as one of the main economic driving forces in heritage cities (Díaz Parra, 2022). However, this is accompanied by major concern about the impact of cultural tourism, with a growing number of consequences as time progresses, as can be seen from the actions of bodies such as the European Parliament (Peeters et al., 2018)

At the outset, an element we find closely linked to these processes is gentrification, the process of urban transformation in neighbourhoods – usually historic ones. This situation, which tends to be linked to socio-economic conditioning factors specifically related to the immediate contexts, can be studied in general terms (Díaz-Parra, 2015). Thus, gentrification could be defined as a process of revalorization of an urban sector within the city, usually the historic centre, prompting a movement for demographic renewal in which a neighbourhood in a state of decline comes to house residents with a higher spending power, or more competitive uses, usually linked to ecommerce (Báez, 2019). This also leads to issues in terms of identity, as the working classes and traditional activities eventually disappear or - at best - move to expansion zones in the city’s periphery, as seen throughout the 20th century.

In addition, the concept of ‘touristification’ arises. This concept, which has gained widespread prominence in recent years, emphasizes a gentrification that is far more localized in terms of its intent. According to Jover and Díaz Parra (Parralejo & Díaz-Parra, 2021), we speak of touristification when describing gentrification in city centres where the origin and end of the process is tourism in and of itself, while tourists are considered the social entities which replace the population previously occupying this urban fabric. A major distinction can be made between both concepts as gentrification does not necessarily imply a depopulation process caused by occasional settlement, but touristification risks focusing land use on consumers of temporary leisure, rootless and in constant movement (Rescalvo & Báez, 2021). It also interferes in the land market, increasing speculation within the local market and creating a rental market which is geared towards the sometimes-excessive revalorization of certain parts of the city (Rescalvo & Báez, 2021). This ultimately brings about a situation of inequality, wearing down residents who have traditionally occupied these areas and who eventually admit defeat when faced with financial interests seeking to dedicate built-up land to almost a single use: tourism (Parralejo et al., 2022)(Mínguez et al., 2019).

It is at this point that the role of short-term rentals comes into place, with platforms such as Airbnb and Homeaway increasing the number of these rentals in recent years. The high demand for tourist accommodation in recent decades, which hotel facilities in the city are no longer able to accommodate, has led to these becoming obsolete.

The particular case of Seville provides us with an interesting case study as it is a heritage city with a robust economic policy based on tourism, which is one of its financial pillars. With a population of 681,988 for the year 2022 according to the most recent census for the Spanish National Statistics Institute, there is an average monthly flow of 170,000 temporary visitors (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). This amounts to almost a third of the population residing full-time in the city. The city must therefore be equipped to offer tourist accommodation to a high number of people in a very limited timespan, which hotels are ill-equipped to cope with. In view of the above, the short-term rental infrastructure has increased its prominence in the city, where in the year 2018 there were over 10,000 tourist apartments.

The final result of all the above, specifically in terms of the Ayuntamiento de Sevilla [Seville Town Council] and above all the Gerencia de Urbanismo [Town Planning Department], is the existence of an obsolete General Plan which remains practically unchanged since it was passed in 2006, except for the odd modification. Due to a lack of planning, it fails to provide sufficient protection to the current urban fabric, where an intense process of tourist gentrification and depopulation of the city centre is taking place. The value of sustainability, understood as the combination of cultural, social, economic and environmental agents, is in jeopardy and possibly even at risk of disappearing in the face of a situation of decline.

In short, these agents are linked to the interactions and relations between individuals and groups in a given society (social); those linked to the economy and factors which affect the economic prosperity and wellbeing of a population (economic); and those referring to defining elements of the culture and identity of a community (socio-cultural).

This article aims to assess the potential risks of touristification in the city centre, focusing specifically on the concept of sustainability in economic, social and cultural terms in a short time span in the recent past. A series of final conclusions will be extracted from an analysis carried out on these three blocks to evaluate the relationship between the evolution of the agents reviewed and a possible gentrification process.

2. Methodology

An individual analysis was carried out on three of the four aspects which currently make up the value of heritage sustainability in the district of Casco Histórico. This value rests on four aspects in total: social, economic, cultural and environmental. The study will focus on the first three aspects, examining a 5-year period in the recent past, from 2015 to 2020, using any available and up-to-date data from different sources for analysis. It will focus on the district of the Casco Histórico, one of the city’s most representative enclaves, where greater social movement has been detected, making the analysis of the current dynamics and relevance to the current context in the city of particular interest.

Open source ArcGIS software is used to enter the different data combined in a model created for case study analysis.

The data obtained for the analysis of social aspects was mostly from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística - INE [Spanish Statistical Office] whose data coincide with those found in the Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía – IECA [Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia], as well as the Municipal Census and Municipal Register for the city of Seville, made available by the Statistics Service of the Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. Finally, the demographic data for the different neighbourhoods in the city were obtained from the Statistical Analysis of the city of Seville, also carried out by the Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. This last source is particularly useful as it breaks down demographic data by district and neighbourhood, enabling the superimposition of any data analysed and the real situation as observed in the case study, while the other sources were used for the comparison with the demographic total of the city. However, the timescale is problematic as it covers the period between 2013 and 2017, the year of its publication. These data were used for the analysis of demographic movement within the neighbourhood, applying a hypothesis to the analysis of the development of processes in which factors including touristification act upon it, causing these demographic movements.

Data for economic analysis were obtained from the Statistical Yearbook for the city of Seville, drawn up by the Ayuntamiento de Sevilla from 2016 to 2020. In this case, data relating to the average income per person and per neighbourhood were obtained for the period between 2015 and 2018. Furthermore, the values for land sale and rental compared to other surrounding areas are also relevant as quantifiable data for the speculation which has appeared in recent years. The information accessed covers the period between 2016 and 2020.

The socio-cultural aspect, viewed here from the angle of appropriation and identity of residents in relation to the neighbourhood was studied taking into consideration the social factor as both are closely linked. The offer for rental accommodation was analysed and compared to residences occupied full-time by the population, quantifying the current weight of occupational demand of short-term accommodation and its effect on both the area and permanent residents. Data were extracted from open source portal Datahippo which offers information up to 2018 for all the tourist rental advertisements on offer on the main search platforms (Airbnb, Homeaway). This was complemented with data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística , including the number of tourists visiting the city. Furthermore, information relating to identity and appropriation of the area was provided by numerous associations and collectives collaborating in citizen participation activities. Data at district level were considered to represent all neighbourhoods within it.

The main Assets of Cultural Interest, as well as the three World Heritage Assets found in the city (Alcázar, Cathedral and Archivo de Indias), were also studied at district level. These are considered to be the main foci attracting tourism.

Three individual analyses were interconnected to extract general results as it is recognized that some parts of the process intervene in others, indirectly or directly.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic analysis

The demographic analysis shows a tendency in the city of Seville to lose resident population. Between 2015 and 2020, total population decreased by only 0.36% (693,878 inhabitants in 2015 to 691,395 in 2020). However, the year 2019 shows a minimum peak, albeit with a downward trend, with 688,592 inhabitants, while the following year saw a slight demographic increase (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). On a smaller district scale, no major movement was observed in 2016 and 2017, the only periods which could be obtained through the document for Statistical Analysis for the city of Seville (Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 2017). However, this was not the case for the districts of Sevilla Este – Alcosa - Torreblanca and Macarena, all of which gained approximately 1000 inhabitants in the space of a year.

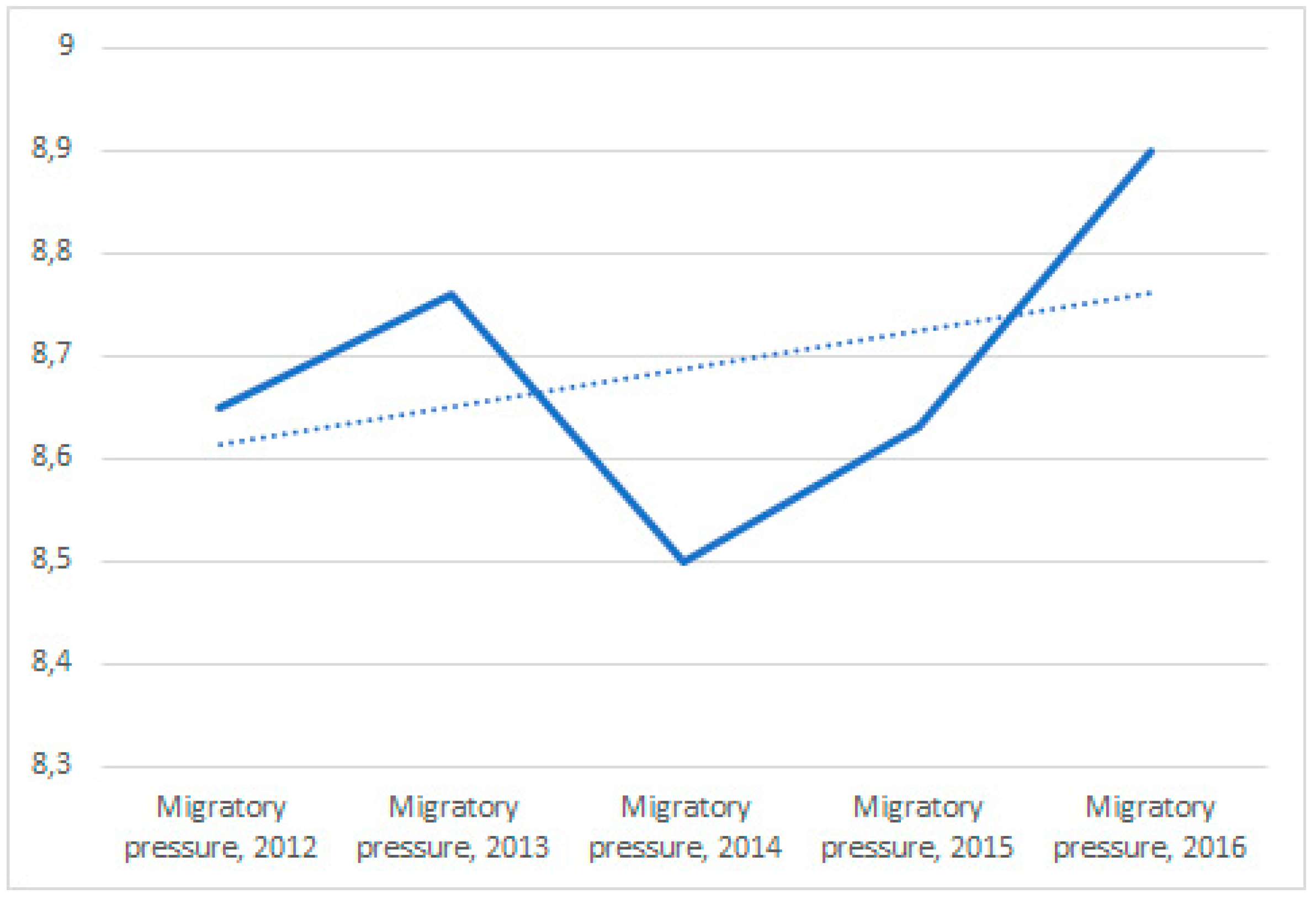

Nevertheless, specific analysis was carried out at neighbourhood level within the Casco Histórico district in order to see the population movements for 2016 and 2017. Although few modifications were observed notable changes were apparent in intervals for every 40-50 inhabitants lost. This did not apply to neighbourhoods such as Museo (20), Alfalfa (90) and Encarnación – Regina (40) where resident population increased in these years. It should be noted however that the above information does not provide relevant information on gentrification so that the migratory pressure of these neighbourhoods, also included in the Statistical Analysis for the city of Seville, was used as reference instead. This value shows the percentage of foreign visitors in relation to the total resident population (

Figure 1). In the case of the district of Casco Antiguo this value is 9%, four points higher than the average for Seville. Despite not falling within the period studied, as records were available from the year 2012 onwards it was possible to forecast the trend in later years.

Figure 1 shows an upward trend line, showing that in years to come the district will be liable to an increase in pressure from the migrant population establishing their residence in these city centre neighbourhoods.

3.2. Economic analysis

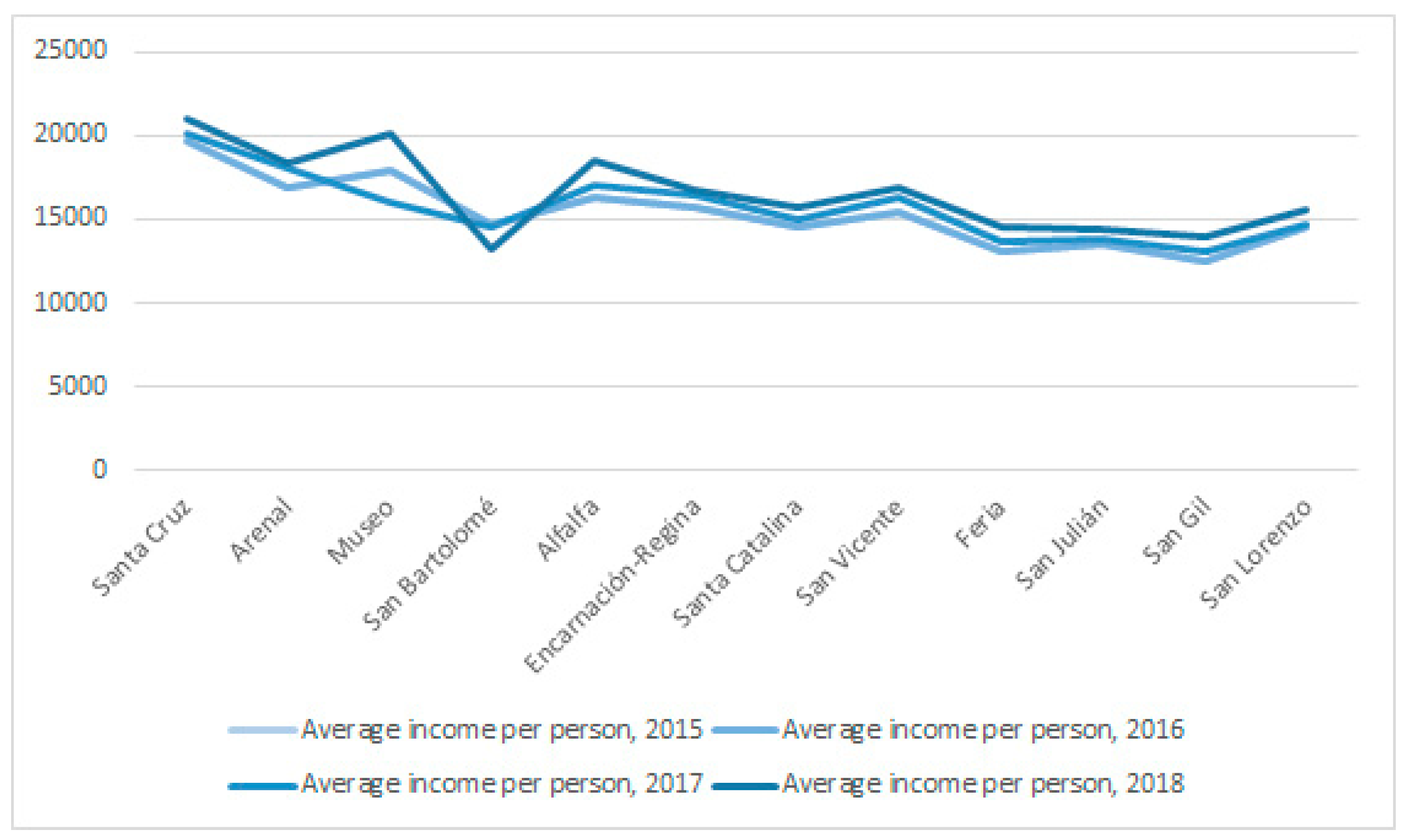

An initial economic assessment was carried out on the average per capita income in the different neighbourhoods of the Casco Antiguo district from 2015 to 2018 (

Figure 2). A series of significant trends and variations were identified based on the evolution of the values compiled by the Statistics Service (Ayuntamiento de Sevilla). Relatively homogeneous income values were observed for the year 2015, with an average of 15,000 euros per person. However, this was clearly an upward trend, with values increasing in all the neighbourhoods. Substantial growth was recorded for 2017, with values ranging between 16,065 and 20,177 euros per person. For the final period analysed, 2018, a final upward trend could be observed, with increases in all except in the neighbourhood of San Bartolomé, where it occasionally decreased, and also in the neighbourhood of Museo, where a peak disrupted the trend for the other years and neighbourhoods. These data point to a gradual increase in the wealth of the central neighbourhoods of this district, despite lingering differences between both of these neighbourhoods.

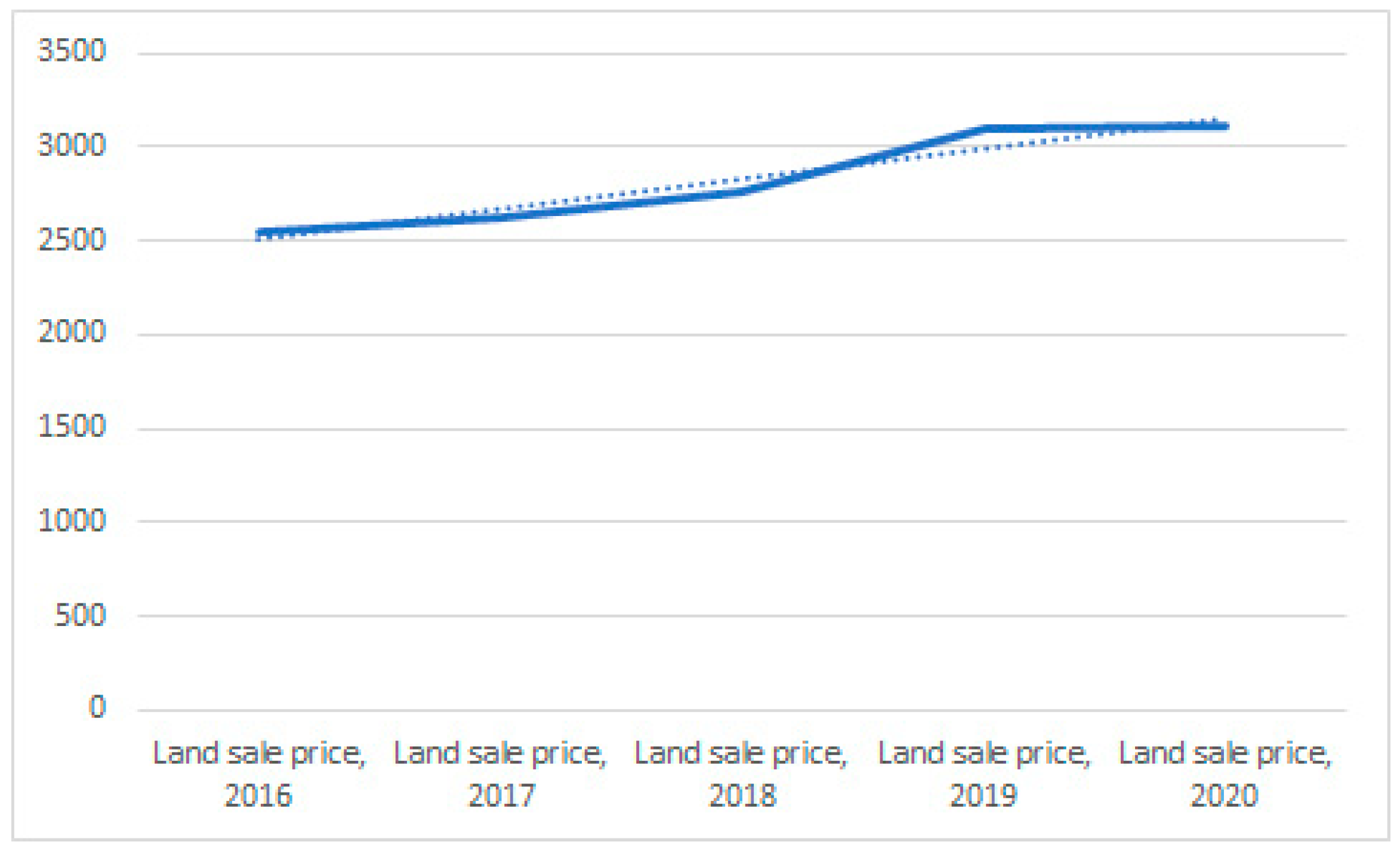

Furthermore, land sale value was also revised using the data available from the Statistics Service, originally obtained from the Fotocasa website. In order to calculate the data for analysis the annual average for land value was calculated, based on monthly data obtained and calculated as €/m

2 for the general value of the district of Casco Antiguo. The graph below shows the evolution and trend of the sales value from 2016 to 2020 (

Figure 3).

The price per square metre was 2546.28€ in the year 2016, with progressive increases in value recorded until 2020, when it reached the amount of 3118€. Overall, compared with the rest of the city, the average land sale value for Seville was 2091€/m2 in 2020. This shows how the value in the city’s historic centre exceeded the average value by a third, which is represented as an example of inflation in the property market.

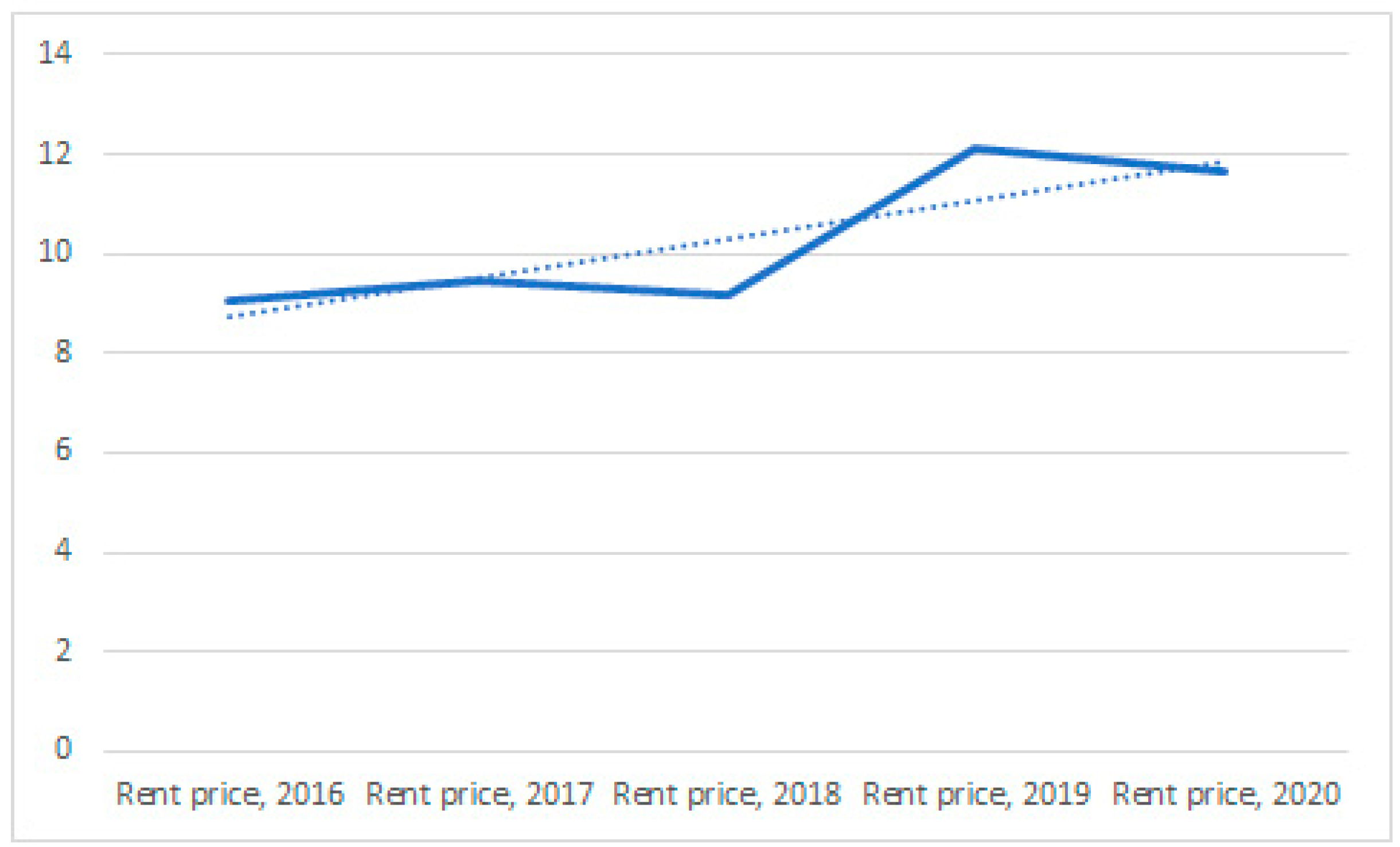

In terms of the rental market, the average in Seville for the same period ranged between 7.45 €/m

2 in 2016 and 9.73 €/m

2 in 2020 (

Figure 4). However, the Casco Antiguo district again showed higher values compared with the rest of the city.

Figure 4 shows how the rental values in this district, also recorded as an annual average in the Statistics Service and obtained from the Fotocasa webpage (9.05 €/m

2 in 2016, 9.46 €/m

2 in 2017, 9.18 €/m

2 in 2018, 12.12 €/m

2 in 2019). Following the major increase observed in 2019 in relation to previous years this average then decreased to 11.63 €/m

2 in 2020. Once again, an upward trend line was observed with the gradual increase in price of rentals for long-term residence.

3.3. Socio-cultural analysis

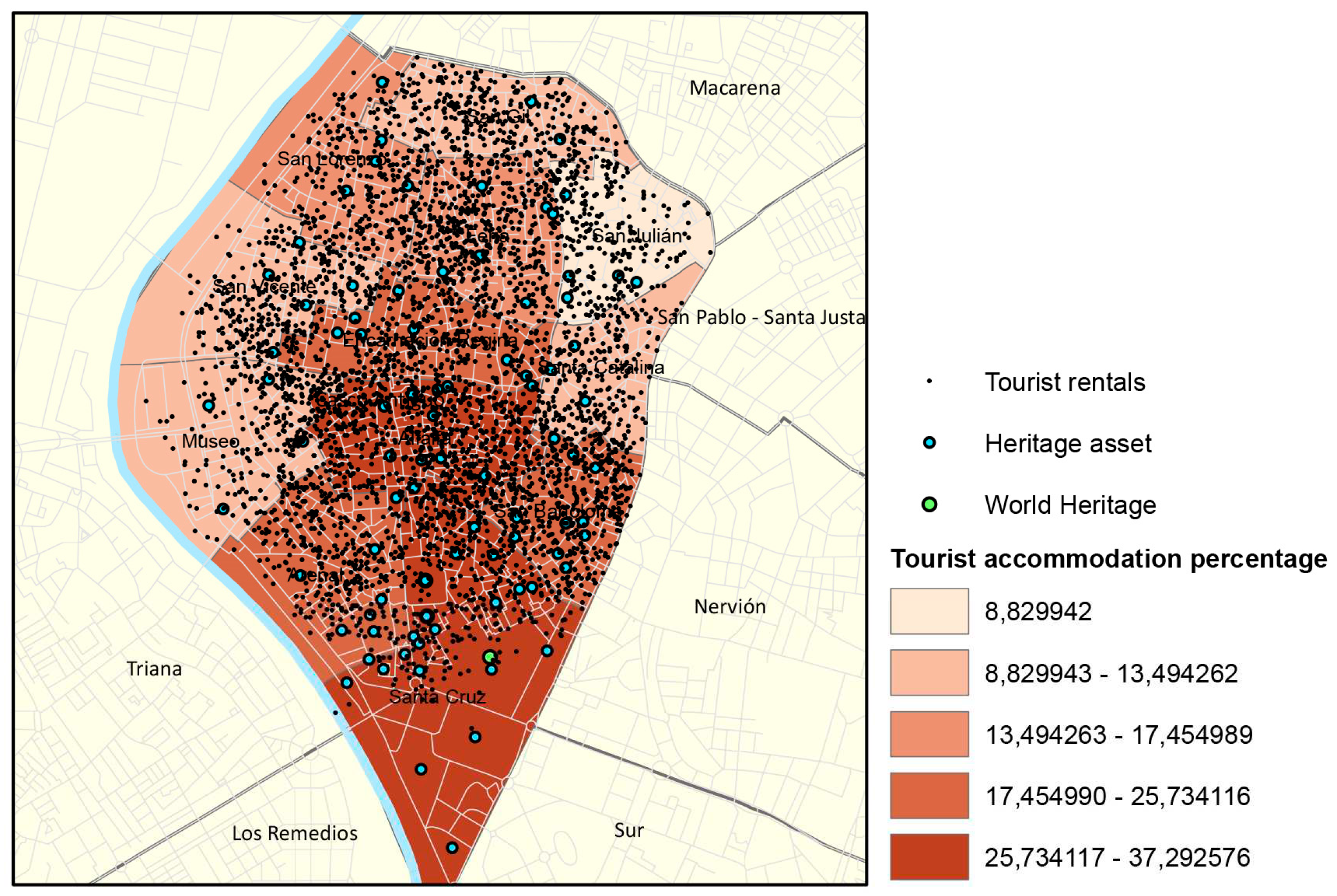

Finally, a socio-cultural analysis was carried out on the impact of the accommodation for temporary rental in the district, as this is one of the major effects of touristification increasing pressure on the resident population, and in turn on the environmental values considered in this section. Data were entered into the ArcGIS model in order to identify all the points representing an apartment featured on the Airbnb website for the city of Seville as of 02-10-2018. The total number of housing units per neighbourhood was also obtained from Statistical Analysis to contrast the percentage of accommodation used for tourist purposes.

Figure 5 shows the major concentration in the district of Casco Histórico, with a high number of apartments devoted to tourist use. The same is observed in the Triana district, albeit on a smaller scale, as a very high concentration of tourist rentals is also found in the area by the river.

In the specific case of the Casco Antiguo district the following analysis data were obtained: in 2018, 4840 of the 8815 tourist apartments recorded for the entire city of Seville were located in the district of Casco Histórico, and this single district accounted for 50% of the short-term rental market. The total of housing units in the district, 27187 in 2017 according to the Statistics Service, was also analysed. Therefore, for the year 2018 the percentage of dwellings in the entire district dedicated to short-term rental represented 17.8% of the overall total for accommodation.

A detailed study of the individual neighbourhoods of the district provided the following data:

Figure 6 shows the neighbourhood with the highest percentage of tourist accommodation compared to permanent residence is that of Santa Cruz, where 37.29% and 427 of the neighbourhood’s 1145 dwellings were devoted to this temporary use. This was followed by the neighbourhood of Alfalfa (32.35%) with a total of 2241 dwellings, 725 of which were tourist accommodation. In descending percentage order these neighbourhoods are followed by the neighbourhood of Arenal (24.89%), San Bartolomé (25.73%), Encarnación – Regina (21.76%), and a final group incorporating the rest of the neighbourhoods, averaging approximately 15%.

In the Casco Histórico district in Seville there is a total of 86 heritage assets according to the section on Spatial Reference Data, within the Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. The plan shows an equal distribution throughout the district, albeit with a greater heritage concentration in the centre-south sector, coinciding with the neighbourhoods able to accommodate a larger number of these tourist rentals.

Finally, as regards the defence of identity and appropriation, its evolution was studied by different bodies and collectives at district level in order to present some sort of quantification of the importance of long-term residents defending a series of heritage values against great pressure from tourism. Between 2015 and 2017 a total of 11 registered bodies (Statistics Service, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 2017) was recorded. These included neighbourhoood associations promoting and calling for better living conditions, citizen participation, security, sustainable urban development, a solution to housing and location issues, and defending specific points. This was considered a sign of neighbourhood activity within these bodies. One of these associations disappeared in 2018, bringing the total to 10, which remained the same until 2020, when it increased to 12. Therefore, there was a slight increase in the number of these collectives within the relative stability displayed in the period under study, reflecting an emerging concern for the current situation.

4. Conclusions

The analysis carried out in this article has presented a brief overview of the evolution of a series of reference aspects. These served to ascertain the presence or absence of gentrification processes, and more specifically, of touristification as origin and root cause of the current situation. Although this analysis was carried out in three distinct blocks, the data obtained had to be cross-referenced as they interacted within a complex system where certain parts affected others, either directly or indirectly.

Firstly, a negative demographic effect was observed, decreasing on a local scale as well as within the specific district analysed. When contextualized against other data increases were also observed in both the rent prices for habitual residences and the land sale price. This suggests that the sector has undergone a process of revalorization, as when compared to other levels in the rest of the city, inflation was observed in the price per square metre due to its strategic location within the city centre. An upward trend was also observed in the per capita income for the different neighbourhoods in the city, although at times this remained out of step with the development of the land market. This ultimately led to depopulation, with habitual residents being forced to move to areas in the city periphery, which offered more affordable housing rental and purchase prices.

At the same time, the use given to these dwellings has also transformed slightly, as many of these former homes had become an asset for financial gain within what is currently a macrosystem seeking to privatize the hospitality offer. This change in use is currently very aggressive as it takes place within an urban system that was previously consolidated to combine traditional activities and measured tourism but currently causes a situation of imbalance.

The appearance of neighbourhood associations calling for the safeguarding of the identity and appropriation of these neighbourhoods also reflects a collective feeling for the protection of a series of values which, as mentioned in the introduction, are eroded or in the worst case eventually disappear. The traditional population, deeply rooted with a historic memory, is being forced out to other sectors without being replaced by any other population. This is how we can see that at present there is no general process of gentrification in the historic centre of Seville, but rather a specific touristification process. There is no process of land revalorization or improvement in the quality of life and purchasing power. Instead, we are observing a process of inflation which is leading to the depopulation of this sector of the city, taking with it the traditional identity and values to be replaced by a constantly moving rootless population, merely passing through and causing excessive exploitation of the city.

Although at present tourism is one of the main economic pillars of Seville this is a double-edged weapon as, if gone unchecked, it attacks the environmental values of a given urban enclave. This results in an excessive demand for cultural leisure and ultimately triggers a series of processes where negative connotations are attached to the different aspects reviewed. While gentrification, understood as a theoretical model, need not be a strictly negative process in society as it improves the conditions of a sector and renovates it, we find ourselves facing a very different scenario in this case. This is why the difference was established between both concepts from the beginning, principally based on their connotations and whether or not population is replaced through this process.

Considering the evolution of the city in recent years it is clear to see that it is in the process of recession, mainly because it has concentrated on economic development in a single aspect, tourism. The organisms in charge of Seville, such as the Ayuntamiento and its Gerencia de Urbanismo, should begin to take a stance and direct their policies against this situation, renovating and developing sustainable tourism models different from those seen since the late 20th century. Thus, a solution can be found for the present problems which affect the historic centre of Seville.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The English revision of this text was funded through the Internationalization Grant by the Instituto Universitario de Arquitectura y Ciencias de la Construcción in the framework of the Seventh Research and Transfer Plan of the Universidad de Sevilla.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Báez, J. J. (2019). Geography of shopping in historic districts: Between gentrification and heritagezation. A study case in Seville. Boletin de La Asociacion de Geografos Espanoles, 82. [CrossRef]

- Díaz Parra, I. (2022). Vender una ciudad : Gentrificación y turistificación en los centros históricos [Book]. Editorial Universidad de Sevilla.

- Díaz-Parra, I. (2015). Viaje solo de ida. Gentrificación e intervención urbanística en Sevilla. EURE, 122, 145–166. [CrossRef]

- Mínguez, C. , Piñeira, M. J., & Fernández-Tabales, A. (2019). Social vulnerability and touristification of historic centers. Sustainability, 11(16). [CrossRef]

- Parralejo, J. J., & Díaz-Parra, I. (2021). Gentrification and Touristification in the Central Urban Areas of Seville and Cádiz. Urban Science, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Parralejo, J. J., Díaz-Parra, I., & Pedregal, B. (2022). Sociodemographic processes and tourist rentals in historic centers. The cases of Seville and Cadiz. Eure, 48(145), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., & Postma, A. (2018). Research for TRAN Committee − Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses. Available online: http://bit.ly/2srgoyg (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Rescalvo, M. B., & Báez, J. J. (2021). Landscapes of touristification: A methodological approach through the case of Seville. Cuadernos Geograficos, 60(1), 13–34. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/index.htm (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Anuario Estadístico de la ciudad de Sevilla, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, 2015-2020. Available online: https://www.sevilla.org/servicios/servicio-de-estadistica/datos-estadisticos/anuarios/anuario-estadistico-de-la-ciudad-de-sevilla-2020 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Indicadores demográficos de Sevilla, 2017, Servicio de Estadística, Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. Available online: https://www.sevilla.org/servicios/servicio-de-estadistica/datos-estadisticos/indicadores-demograficos/analisis-indicadores-demograficos.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- DataHippo. Tourist dwellings. Available online: https://datahippo.org/es/ (accessed on 13 October 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).