Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Common Problems with ERM Implementation

- An over-emphasis on reporting

- Not enough injection into the decision-making processes

- Too much adherence to a static process

- Treating risks as discrete items

- The misuse of models

- The belief that all risk is bad

- A lack of role clarity

2.1. An Over-Emphasis on Reporting

2.2. Not Enough Injection into Decision-Making Processes

- Strategic planning. Risks are represented in the O (opportunities) and the T (threats) of SWOT. It is a natural fit.

- Business planning. Using bottom-up risk assessments as a driver for decision making and trade-offs about where to allocate resources, and ensuring the plans are aligned with the business strategy.

- Outsourcing. An outsourcing contract is not just the allocation of money and services; it also allocates risks between the two parties. So why not transparently identify the risks related to the body of work that is being outsourced, use the contract to explicitly assign the risks between the two parties, and figure out how to make sure that they are oriented towards managing the critical things? (Quail 2021c).

- Investment prioritization. For every dollar available to the business, where should that money be used? One of the factors should be where can that dollar do the best in terms of mitigating risks and managing uncertainty about the achievement of the business objectives. Embed risk management right into those prioritization processes (Toneguzzo 2021).

- Technology projects. There is a saying that there is no better way for a chief information officer to lose their job than to try and replace the enterprise resource platform or other enterprise technology in the business. It is risky work. Therefore, it follows that risk assessments should be done; not just the Project Management Office tools and methods, but in terms of scoping, resourcing, timing, vendor selection, and the all-critical go/no-go decision before go-live and the resulting effects (Winters 2021).

- Regulatory compliance management. Many businesses are involved in very complicated regulatory environments and it can be a challenge for organizations to prioritize where to allocate resources for compliance management and control. Risk management can help organizations prioritize resources by exploring this question: Which of these regulatory requirements, if not met, has the bigger potential to cause harm or affect the achievement of the stated business objectives?

2.3. Too Much Adherence to a Static Process

- Black Swans, or extreme-end-of-tail risks (Taleb 2010). These risks are very unlikely but have the potential for extreme impact. The tools that one normally uses for prioritizing risks does not work anymore. Instead, one needs to identify other ways to learn from potential Black Swan type scenarios as a kind of thought-experiment: i.e., if one of these scenarios occurs, is the organization resilient enough to be able to react in time, or at least faster and better than the competitors?

- Scenario planning exercises as pioneered by Royal Dutch Shell (see Schwartz 1991 and Wilkinson and Kupers 2013). Remember: the ISO definition of risk is the effect of uncertainty on objectives. What scenario planning does is test to see whether those are the right objectives in the first place. In this way, it's about risks not to the strategy, but of the strategy. We note that, in the wake of COVID and climate change concerns and the war in Ukraine, there has been a recent resurgence in the popularity of scenario planning.

- Custom criteria should be developed to help inform decision making, e.g., developing a technology road map for an organization by applying things like priority, opportunity in capacity as well as an assessment of risks in the organization’s ability to deliver.

- ERM can be dovetailed into strategy setting through exercises like the risk appetite process (Quail 2021b, Ismail 2021).

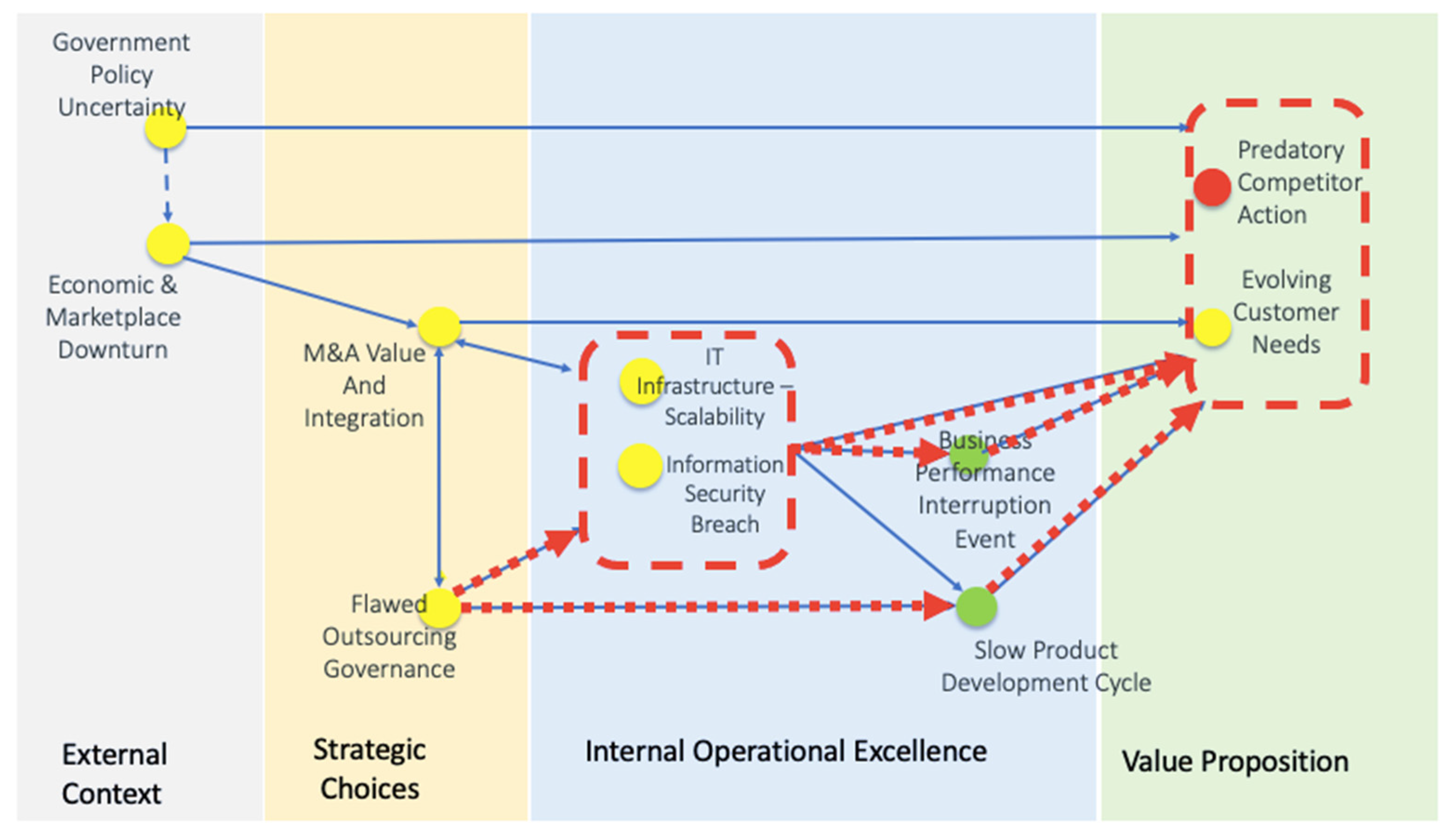

2.4. Treating Risks as Discrete Items

2.5. The Misuse of Models

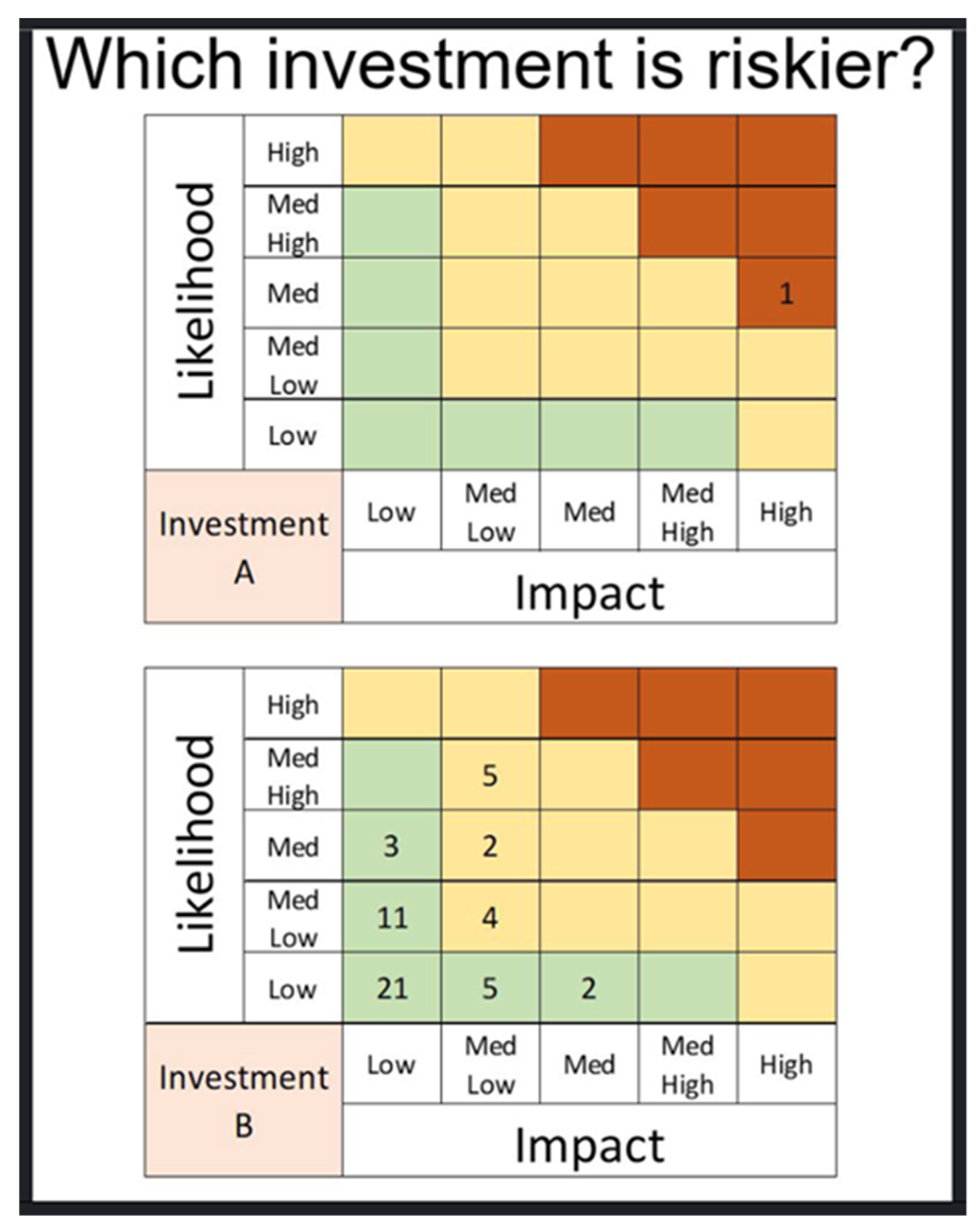

- First, a risk is not a single combination of impact and probability. A risk is associated with the range of outcomes of different probabilities; a risk is a curve, not a point. Now, usually when heat maps plot risks, there is a spot on the map that represents something like a worst credible impact. But that's only for prioritization or to give a vivid summary picture for senior executives or the board of directors. It does not convey nearly enough information to allow anybody to make any kind of actual decision.

- Second, these two risks in these two maps may not be defined in the same way. It could very well be that Investment B involves an array of lower level, more granularly defined risks, and if you added them all up, they might add up to something that is at least as big as the risk in Investment A. So that's another problem with heat maps: the definition of the risk, the scope of the risk, and the scale used when evaluating the risks.

- In Investment B, should one of these risk events occur, there may be a domino effect, and once it finishes playing out, there may be a much bigger impact than was identified in the heat map for Investment A.

2.6. The Belief that All Risks Are Bad

- Some organizations combine risk and insurance. Insurance is about the avoidance of loss, i.e., downside.

- Others have combined ERM with Internal Audit. The role of Internal Audits is basically to identify potential weaknesses in internal controls, i.e., downside.

- Others place their ERM group so they report to a General Counsel. What's the General Counsel's job? Avoiding legal or commercial risk exposures, i.e., downside.

- For which ones do we expect that the pathway, from where the organization is to where it wants to be, is a squiggly/non-linear line, where the organization needs to be responsive and resilient? That suggests a higher risk appetite.

- Which of the strategic objectives are ones where a small change or volatility in a key performance indicator (KPI) is going to indicate that the organization is lacking in control, and it would be better to drop everything and figure out what’s wrong? That suggests that there is a low-risk appetite with respect to that objective.

2.7. A Lack of Role Clarity

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- (Alviniussen and Jankensgard 2015) Alviniussen, Alf and Jankensgard, Hakan, 2015. Chapter 24 Value and risk: Enterprise risk management at Statoil. In J. Fraser, B.J. Simkins, & K. Narvaez (Eds.), Implementing Enterprise Risk Management: Case Studies and Best Practices. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Beasley and Branson 2022) Beasley, Mark., and Branson, Bruce. 2022. 2022 The State of Risk Oversight: An Overview of Enterprise Risk Practices, 13th Edition. North Carolina State University Enterprise Risk Management Initiative.

- (COSO 2017) COSO. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission. 2017. Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework.

- (Fraser 2016) Fraser, J. R. 2016. The role of the board in risk management oversight. In R. Leblanc (Ed.), Handbook of Corporate Governance. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- (Fraser et al. 2021a) Fraser, John R.S., Quail, Rob, and Simkins, Betty J. 2021a. COVID-19: The risk management part is unfinished, CFO (January 21). Available at: https://www.cfo.com/corporate-finance/2021/01/covid-19-the-risk-management-part-is-unfinished-2699/.

- (Fraser et al. 2021b) Fraser, John R.S., Quail, Rob, and Simkins, Betty J. 2021b. The history of Enterprise risk management at Hydro One Inc. Journal of Risk and Financial Management: 14(8). [CrossRef]

- (ISO 2018) International Standards Organization. 2018. ISO 31000, Risk management – Guidelines.

- (Ismail 2021) Ismail, M. 2021. Chapter 23 Organizational Decision Making. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. Second Edition (pp. 459 to 472). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Kaplan and Mikes 2012) Kaplan, Robert S., and Anette Mikes. 2012. Managing risks: A new framework. Harvard Business Review Vol. 90 (6, June).

- (Lowenstein 2000) Lowenstein, Roger. 2000. When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management. Random House.

- (Mikes 2021) Mikes, Anette. 2021. Chapter 8 Becoming the lap bearer: The emerging roles of the chief risk officer. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. (pp. 369 to 390). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Quail 2021a) Quail, R. 2021a. Chapter 19 How to plan and run a risk management workshop. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. (pp. 369 to 390). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Quail 2021b) Quail, R. 2021b. Chapter 23 Risk appetite. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. Second Edition (pp. 459 to 472). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Quail 2021c) Quail, R. 2021c. Chapter 33. Risk management and outsourcing. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. (pp. 369 to 390). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Sarbanes-Oxley 2002) Sarbanes-Oxley Act. 2002. Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress.

- (Schwartz 1991) Schwartz, Peter. 1991. The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World. Doubleday.

- (Stonebrook 2021) Stonebrook, Ian. 2021. How sportswear sold streetball. Boardroom. August 12: available at https://boardroom.tv/sportswear-streetball-and1/.

- (Taleb 2010) Taleb, Nassim. 2010. The Black Swan: Second Edition: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Random House.

- (Toneguzzo 2021) Toneguzzo, Joseph P. 2021. Chapter 219. How to allocate resources based on risk. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- (Wilkinson and Kupers 2013) Wilkinson, Angela and Kupers, Roland. 2013. Living in the futures. Harvard Business Review (May).

- (Winters 2021) Winters, Mike. 2021. Chapter 36. Managing risk associated with project delivery: A how to guide. In J. Fraser, R. Quail, & B.J. Simkins (Eds.), Enterprise Risk Management: Today’s Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow’s Executives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).