Submitted:

17 November 2023

Posted:

20 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

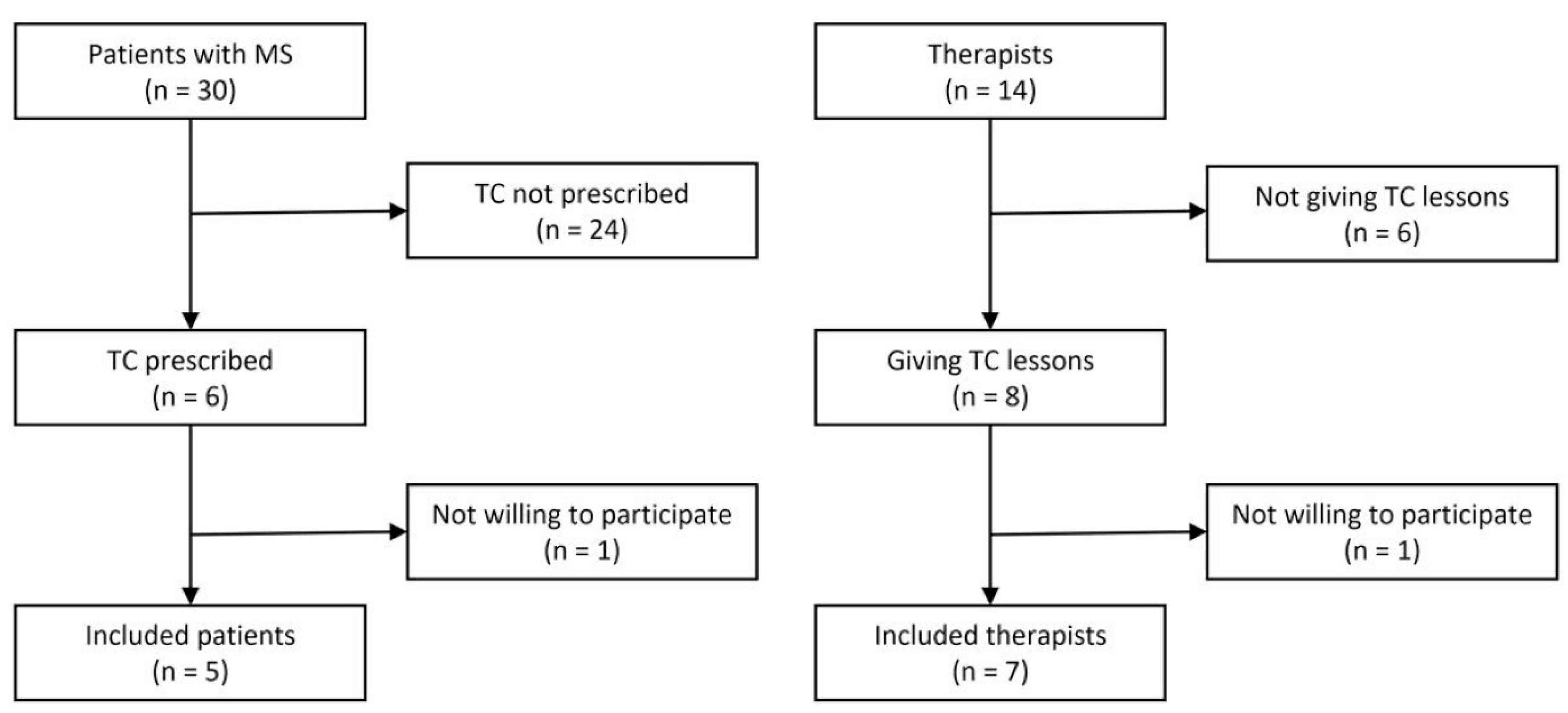

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data collection

2.4. Data analysis

2.5. Ethical considerations

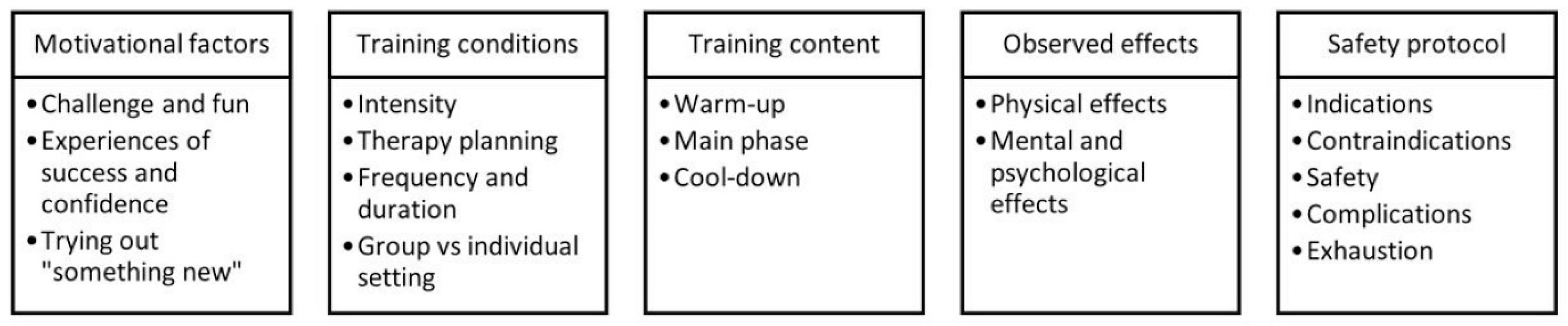

3. Results

3.1. Motivational factors

And the big advantage is that the exercises are very short, and then you immediately have a success – and if you have no success, then you think to yourself that it also does not matter. […] But it is simple, uplifting. It is good for the mind. It raises your self-esteem again, and that's a fun factor, where you know: "Yes, if I make it, then it's good, and if not, it doesn't matter."(P2)

“You have quite a tunnel vision, then. For me, it is like this. I do not notice much around me. I am also quite sensitive to noise, but I am highly concentrated. I get into a flow and always want to do things right. So, I do not always want to do things halfway – I just want to do it right.”(P3)

“The motivation is to get it done. So certain movements, whether the basic position or coming up [the wall], reach as high as I can. The nice thing is that you see the result immediately. If it works or does not work, that is just great. And if it does not work, I just do it again. So that is really special, and I really enjoy it.”(P5)

“I liked that although I am thin, I have quite a bit of strength in my hands, and I can use that. I have a good feeling because I know: "You can do that." And I am not at the mercy of the feeling that I am going to fail.”(P3)

3.2. Training conditions

“And that is simply what distinguishes it from physiotherapy, where it is quite clear what is happening, for instance, squatting down or with the heels on the floor – just as great. It is just that with climbing, there is also the aspect of fun, while at the same time, it is somehow very intense, but that is good.”(P5)

"When you face challenges in climbing, you can't just take it lightly. In other forms of training, you can adjust the weight to your preference; for instance, I could choose to train with 5 kilos. But in climbing, you're contending with your own body weight. That's the weight you must manage."

“Because as a therapist, it starts relatively soon that I play with the intensities. If I see that the person is doing a great job and it is working great, I can think about doing a more difficult exercise for them. If I see that the exercise is already quite demanding, then I can make the next exercise easier.”(T2)

“I just have to rest for a short while after the training. […] Half an hour or hour and then I feel very fit again.”(P4)

“Longer [sessions] would avail to nothing because then you get into exhaustion, and then you are demotivated, because it does not work. So, because it is also a strength exercise, with this trunk stabilization, I think that is a good time interval. Just that long, not longer, not shorter.”(P2)

“It is a group, and group programs are usually just not so specific. Or let me put it this way: it is a clear extra effort if you give two patients completely different exercises.”(T5)

3.3. Training content

“So, what I find good is that the exercises always go out from a fixed basic position, where the basic position always recalls this stability again and again. That is – with the shoulders down and abdominal tension and a bit of squatting – heels up.”(T1)

“And today – I climbed today for the second time – I climbed from wall to wall. It was great, both with overhang, it was really cool. […] It is structured great. First, you learn to do the basics and climb that way. […] Then the arms relaxed, and I actually climbed from right to left and left to right today.”(P5)

3.4. Observed effects

“Of course, [TC is] strengthening the muscles – be it upper arms or grip strength, lower extremities, or trunk stability, respectively. Another effect is, for example, torso stability, spinal stability, posture, but also coordination. And, of course, how to grasp things, how tightly you have to grip in order to be able to hold on. Balance is also trained for people to become a bit more mobile and secure in everyday life and minimize their risk of falling.”(T4)

“In the neck, shoulder, and upper back areas, I notice it already. And, of course, biceps, triceps, you feel very strongly. […] Anyways, you notice the strength, which then just increases a bit. The grip strength is what now just works properly.”(P3)

“I think climbing also has a high motivational character, so the patients gain self-confidence and security. By climbing not only at standing height but also a little higher, I believe that patients gain self-confidence and thus appear more self-assured.”(T4)

“I already felt like I fit in. I think I have improved not only my athletic activity but also my cognitive capability because you just have to think ahead: Where do I step? Where do I reach? […] That is not so easy for me, and that is why I actually found it good that I can combine both in one unit, both physically and then mentally a bit.”(P3)

3.5. Safety protocol

“Well, it also has much to do with self-awareness, which is perhaps not the case with normal strength training, where I sit on the machine and simply move the leg press. There is just not as much body awareness as in climbing.”(T5)

“First of all, they need to have a certain strength in the forefeet – so that they can stand on their forefeet at all – and then hold themselves up with the upper extremities with both hands.”(T2)

“I mean – I have never had the case – but if any extremity would be paralyzed or that somebody has perhaps such feelings of numbness, I imagine that would be difficult. I would not know if that would not be rather frustrating if I felt that way.”(P3)

“I felt safe because the therapist was always behind me, and I know she catches me when something happens.”(P1)

“As a therapist, if you notice that it is unsafe, you can also stand directly behind the patients. That means that if they slip, it is safe so that they do not hurt themselves badly.”(T1)

“Such [mild] pain may occur again and again, in the shoulders, in the knee joint – but nothing more serious.”(T4)

“Once, it was too much for me. I think this morning was intense because I was training in half-hour intervals without a break – first climbing, then eating. And then, I had an intensity tremor in my hands, and then I noticed […] the trembling of the hands became significantly more, and it was difficult to eat.”(P3)

“I have to say that I cannot think of any MS patient who has stopped climbing with me because of fatigue. […] When patients stop, it is usually because of pain; those are more likely to be spine patients. […] Of course, what happens from time to time is that they say beforehand that they are totally exhausted. But then you try to arrange it so the MS patient takes longer breaks.”(T5)

4. Discussion

- Motivational factors

- Training conditions

- Observed effects

Strengths and limitations

5.Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

Disclosure statement

References

- WHO. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Dis-eases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision 2019.

- Tafti, D.; Ehsan, M.; Xixis, K.L. Multiple Sclerosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring, J.; Beer, S. Symptomatic therapy and neurorehabilitation in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2005, 4, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, A.; Marissal, J.P.; Pouyfaucon, M.; Vermersch, P.; Hautecoeur, P.; Dervaux, B. Social participation in patients with multiple sclerosis: correlations between disability and economic burden. BMC Neurol 2014, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, A.; Fox, R.J.; Tyry, T.; Cutter, G.; Marrie, R.A. The association of fatigue and social participation in multiple sclerosis as assessed using two different instruments. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2019, 31, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSousa, E.A.; Albert, R.H.; Kalman, B. Cognitive impairments in multiple sclerosis: a review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2002, 17, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracca, M.; Pontillo, G.; Moccia, M.; Carotenuto, A.; Cocozza, S.; Lanzillo, R.; Brunetti, A.; Brescia Morra, V. Neuroimaging Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iodice, R.; Aceto, G.; Ruggiero, L.; Cassano, E.; Manganelli, F.; Dubbioso, R. A review of current rehabilitation practices and their benefits in patients with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leichtfried, V. Therapeutisches Klettern – eine Extremsportart geht neue Wege. In Alpin und Höhenmedizin; Franz Berghold, H.B., Martin Burtscher, Wolfgang Domej, Bruno Durrer, Eds.; Springer, 2015; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Frühauf, A.; Heußner, J.; Niedermeier, M.; Kopp, M. Expert Views on Therapeutic Climbing-A Multi-Perspective, Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechter, R.B.; Fechtelpeter, D. Climbing for preventing and treating health problems: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ger Med Sci 2011, 9, Doc19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Gong, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y. The Origin, Application and Mechanism of Therapeutic Climbing: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.; Elmenhorst, J.; Oberhoffer, R. [Effect of sport climbing on patients with multiple sclerosis – hints or evidence?]. Neurologie & Rehabilitation. 2013, 4, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Gallotta, M.C.; Emerenziani, G.P.; Monteiro, M.D.; Iasevoli, L.; Iazzoni, S.; Baldari, C.; Guidetti, L. PSYCHOPHYSICAL BENEFITS OF ROCK-CLIMBING ACTIVITY. Percept Mot Skills 2015, 121, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermier, C.M.; Robergs, R.A.; McMinn, S.M.; Heyward, V.H. Energy expenditure and physiological responses during indoor rock climbing. Br J Sports Med 1997, 31, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodio, A.; Fattorini, L.; Rosponi, A.; Quattrini, F.M.; Marchetti, M. Physiological adaptation in noncompetitive rock climbers: good for aerobic fitness? J Strength Cond Res 2008, 22, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruhauf, A.; Sevecke, K.; Kopp, M. [Current state of the scientific literature on effects of therapeutic climbing on mental health - conclusion: a lot to do]. Neuropsychiatr 2019, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimer, J.; Weissert, R. Effects of Sport Climbing on Multiple Sclerosis. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikonja, O.; Curic, K.; Ozura, A.; Jazbec, S.S. Influence of sports climbing and yoga on spasticity, cognitive function, mood and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2010, 112, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRZ Rosenhügel. Available online: https://www.nrz.at/ (accessed on 22.03.2023).

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International journal of qualitative methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppich, W.J.; Gormley, G.J.; Teunissen, P.W. In-Depth Interviews. In Healthcare Simulation Research: A Practical Guide, Nestel, D., Hui, J., Kunkler, K., Scerbo, M.W., Calhoun, A.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software; SAGE Publications Ltd: New York City, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gabler, H. Motive im Sport: motivationspsychologische Analysen und empirische Studien. (No Title).

- Jeng, B.; DuBose, N.G.; Martin, T.B.; Silic, P.; Flores, V.A.; Zheng, P.; Motl, R.W. An updated systematic review and quantitative synthesis of physical activity levels in multiple sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpenverein, D.; Alpenverein, Ö.; Südtirol, A. Hoch hinaus!; B? ohlau Verlag: 2016.

- Gopal, A.; Bonanno, V.; Block, V.J.; Bove, R.M. Accessibility to Telerehabilitation Services for People With Multiple Sclerosis: Analysis of Barriers and Limitations. Int J MS Care 2022, 24, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Sawa, R.; Saitoh, M.; Morisawa, T.; Kagiyama, N.; Kasai, T.; Dinesen, B.; Hollingdal, M.; Refsgaard, J.; et al. Web Portals for Patients With Chronic Diseases: Scoping Review of the Functional Features and Theoretical Frameworks of Telerehabilitation Platforms. J Med Internet Res 2022, 24, e27759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, P.B. Physiology of difficult rock climbing. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004, 91, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, L.; Dabnichki, P.; Langer, A.; Pokan, R.; Zach, H.; Ludwig, M.; Santer, A. The therapeutic effects of climbing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PM&R.

- Gassner, L.; Dabnichki, P.; Langer, A.; Pokan, R.; Zach, H.; Ludwig, M.; Santer, A. The therapeutic effects of climbing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pm r 2023, 15, 1194–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepka, M.; Tos, M.; Boron, M.; Gibas, K.; Krzystanek, E. Relationship between Fatigue and Physical Activity in a Polish Cohort of Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R.; Brown, T.R.; Coote, S.; Costello, K.; Dalgas, U.; Garmon, E.; Giesser, B.; Halper, J.; Karpatkin, H.; Keller, J.; et al. Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Mult Scler 2020, 26, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgas, U.; Langeskov-Christensen, M.; Stenager, E.; Riemenschneider, M.; Hvid, L.G. Exercise as Medicine in Multiple Sclerosis-Time for a Paradigm Shift: Preventive, Symptomatic, and Disease-Modifying Aspects and Perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Motl, R.W. Exercise Training for Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Review of History, Benefits, Safety, Guidelines, and Promotion. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabchi, F.; Alizadeh, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Abolhasani, M. Exercise prescription for patients with multiple sclerosis; potential benefits and practical recommendations. BMC neurology 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Gutiérrez, S.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; de Arenas-Arroyo, S.N.; López-Muñoz, P.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Guzmán-Pavón, M.J.; Torres-Costoso, A. The type of exercise most beneficial for quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2022, 65, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandroff, B.M.; Motl, R.W.; Scudder, M.R.; DeLuca, J. Systematic, Evidence-Based Review of Exercise, Physical Activity, and Physical Fitness Effects on Cognition in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Neuropsychol Rev 2016, 26, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | Sex | Age | Duration of disease (years) |

EDSS score |

TC units attended |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | female | 59 | 22 | 3.0 | 3 |

| P2 | female | 54 | 24 | 3.5 | 6 |

| P3 | female | 35 | 11 | 3.5 | 11 |

| P4 | male | 37 | 5 | 2.0 | 7 |

| P5 | male | 35 | 1 | 2.5 | 6 |

| Code | Sex | Work experience (years) |

TC experience (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | male | 16 | 4 |

| T2 | female | 6 | 3 |

| T3 | female | 20 | 15 |

| T4 | male | 2 | 2 |

| T5 | male | 9 | 9 |

| T6 | female | 12 | 2 |

| T7 | male | 20 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).