Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Varietal evolution

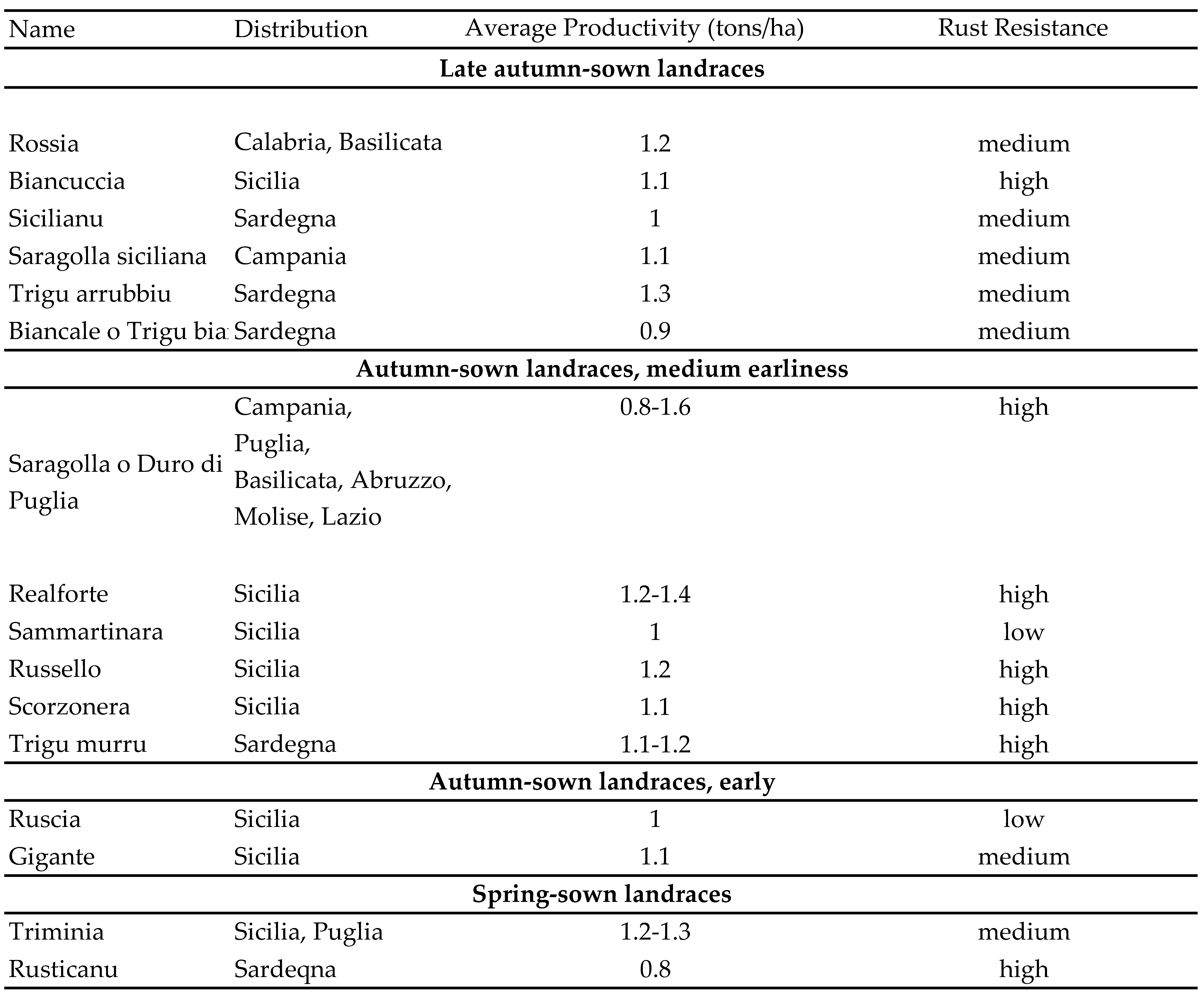

2.1. Landraces and local populations (1800-1920)

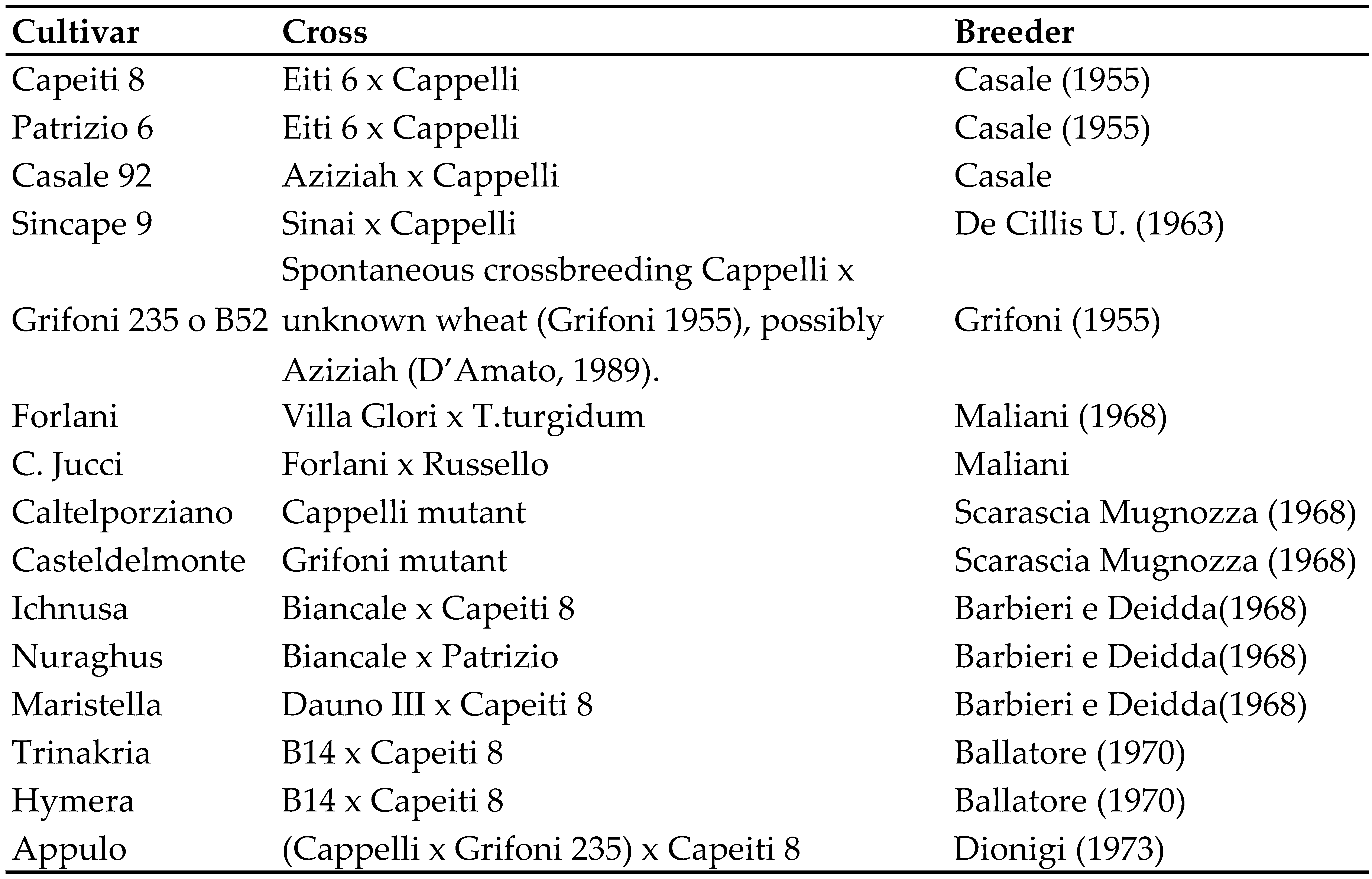

2.2. First period: genealogical selection from local and exotic populations (1920–1950)

2.3. Second period: intra- and inter-specific hybridization and mutagenesis (1950–1973)

2.4. Final period: semi-dwarf cultivars (1974–today)

3. Evolution of grain yield and related traits

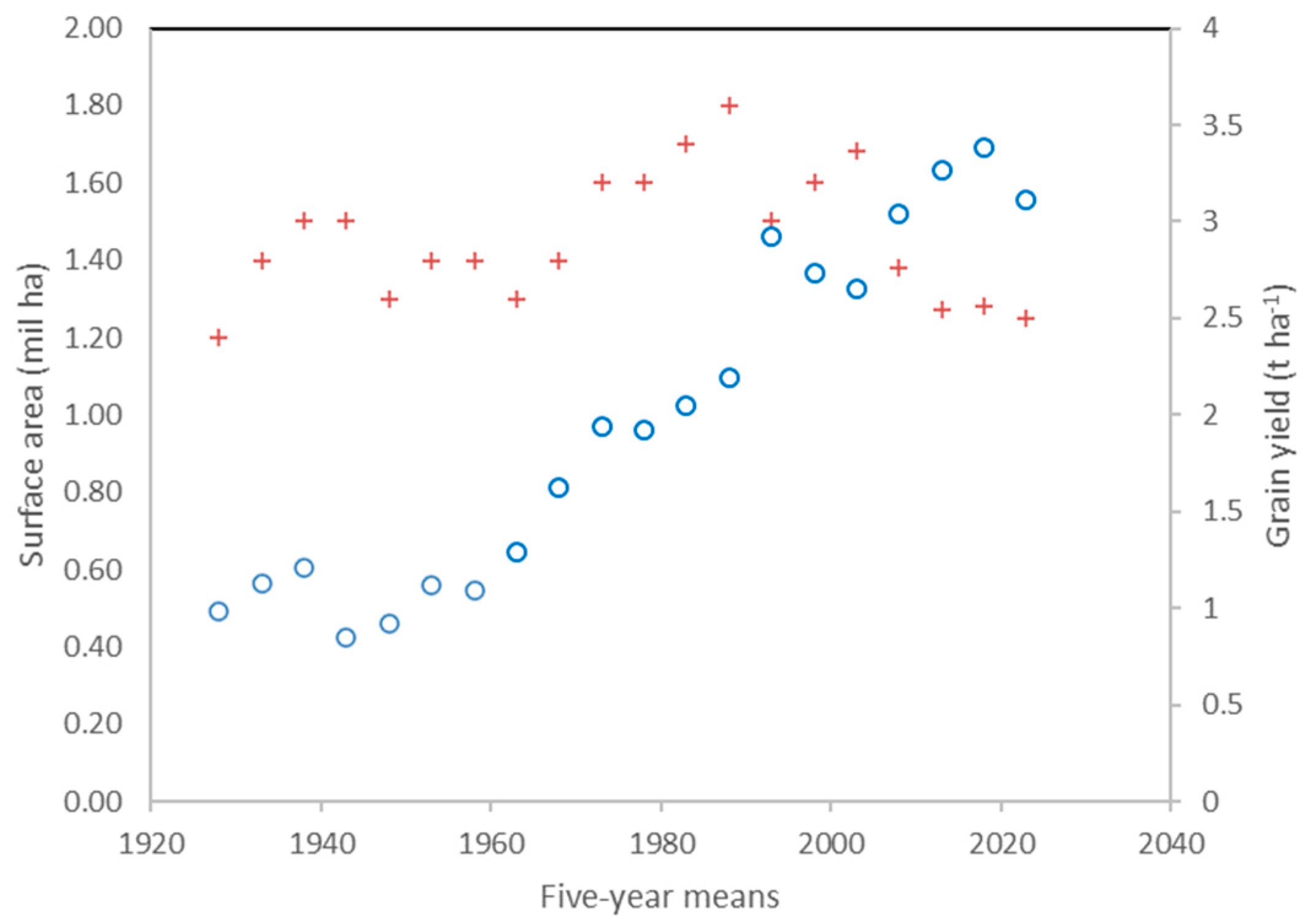

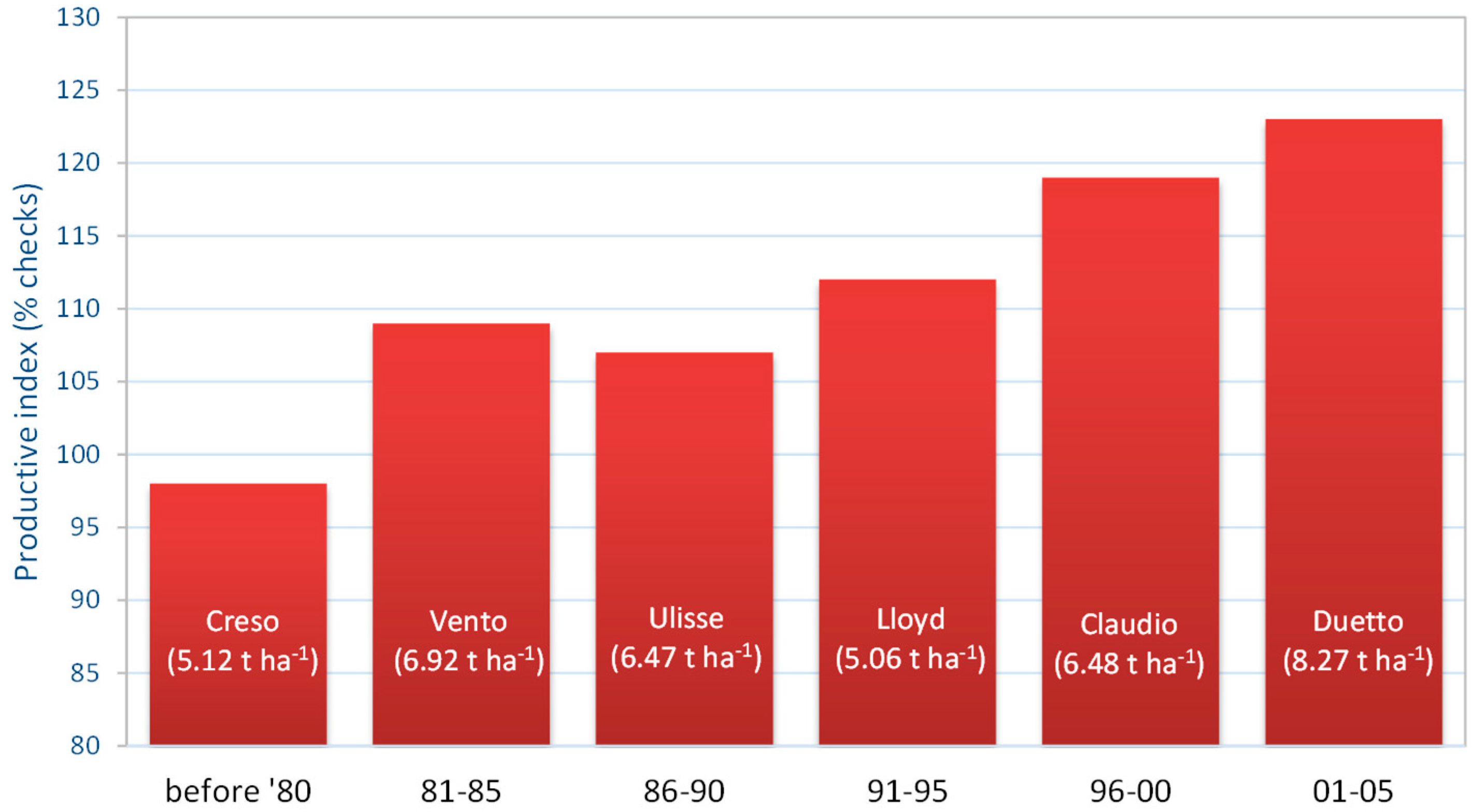

3.1. Grain yield

3.2. Plant height, lodging resistance, HI

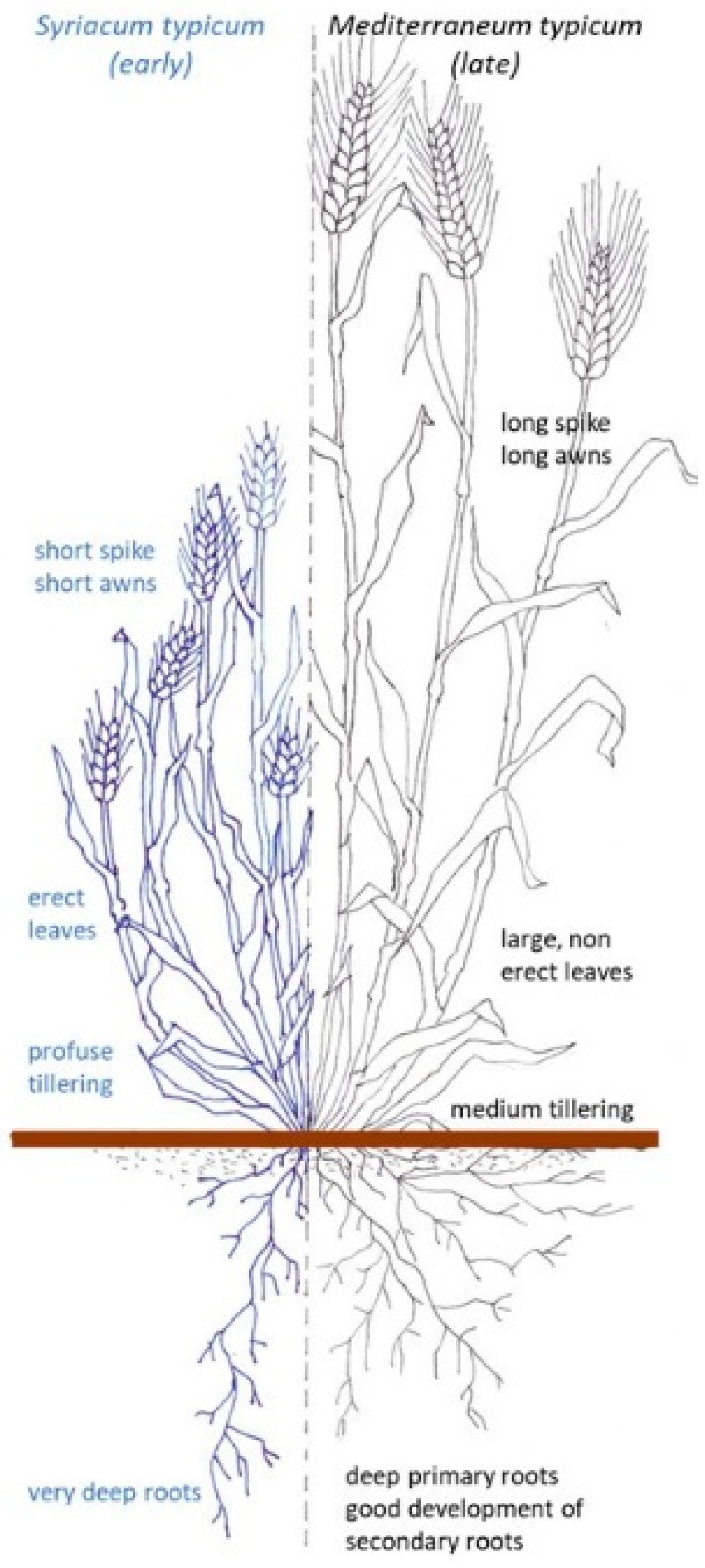

3.3. Leaf and canopy traits

3.4. Phenology

3.5. Nitrogen uptake and use-efficiency

3.6. Grain and semolina quality

4. Future prospects: lessons from the past

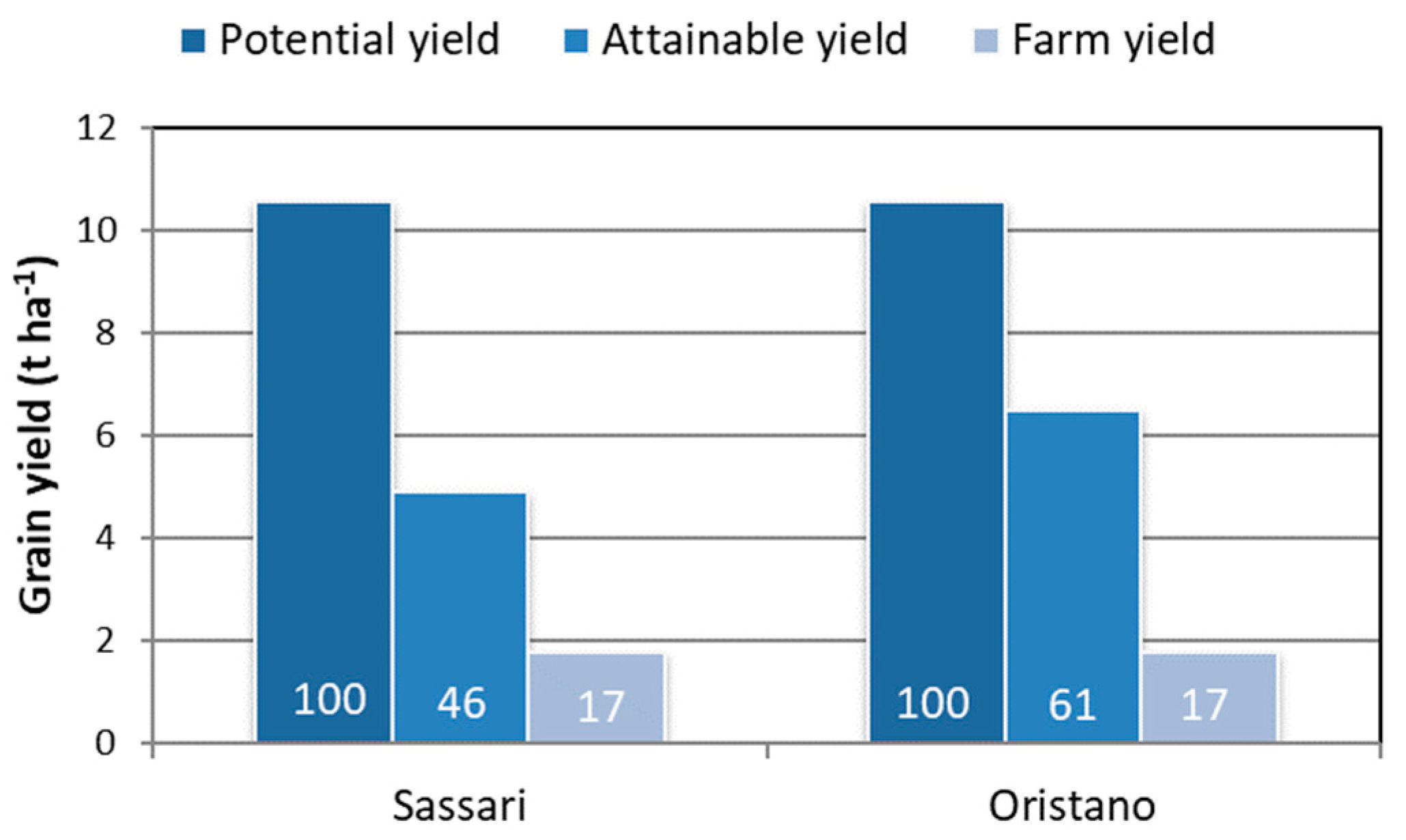

4.1. Grain yield

4.2. Phenology: is the advance in anthesis date still desirable?

4.3. Grain quality: are grain yield and grain protein mutually exclusive?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Royo, C.; Ammar, K.; Villegas, D.; Soriano, J.M. Agronomic, Physiological and Genetic Changes Associated With Evolution, Migration and Modern Breeding in Durum Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 674470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mefleh, M.; Conte, P.; Fadda, C.; Giunta, F.; Piga, A.; Hassoun, G.; Motzo, R. From Ancient to Old and Modern Durum Wheat Varieties: Interaction among Cultivar Traits, Management, and Technological Quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnara, D.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.T. Outlook in Breeding for Yield in Durum Wheat. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Symposium on genetics and breeding of durum wheat; p. 1975.

- Azeez, M.A.; Adubi, A.O.; Durodola, F.A. Landraces and Crop Genetic Improvement. In Rediscovery of Landraces as a Resource for the Future; IntechOpen, 2018; ISBN 1-78923-725-4. [Google Scholar]

- De Cillis, E. I Grani d’Italia. Tipografia della Camera dei deputati. 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Grignac, P. Contribution à l’étude de Triticum Durum Desf, Toulouse, 1965.

- Bozzini, A. Genetica e Miglioramento Genetico Dei Frumenti Duri; Tipografia del libro, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Annicchiarico, P.; Pecetti, L.; Damania, A.B. Relationships between Phenotypic Variation and Climatic Factors at Collecting Sites in Durum Wheat Landraces. Hereditas 1995, 122, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazco, R.; Peña, R.J.; Ammar, K.; Villegas, D.; Crossa, J.; Royo, C. Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.) Mediterranean Landraces as Sources of Variability for Allelic Combinations at Glu-1/Glu-3 Loci Affecting Gluten Strength and Pasta Cooking Quality. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, F.; D’Agostino, N.; Rodriguez, M.; Pavan, S.; Minervini, A.P.; Pecchioni, N.; Papa, R.; De Vita, P. Whole Genome Scan Reveals Molecular Signatures of Divergence and Selection Related to Important Traits in Durum Wheat Germplasm. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzario, S.; Logozzo, G.; David, J.L.; Zeuli, P.S.; Gioia, T. Molecular Genotyping (SSR) and Agronomic Phenotyping for Utilization of Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.) Ex Situ Collection from Southern Italy: A Combined Approach Including Pedigreed Varieties. Genes 2018, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, M.C.; Mercati, F.; Spina, A.; Blangiforti, S.; Venora, G.; Dell’Acqua, M.; Lupini, A.; Preiti, G.; Monti, M.; Pè, M.E. High-Throughput Genotype, Morphology, and Quality Traits Evaluation for the Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Wheat Landraces from Sicily. Plants 2019, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliani, C. Nuove Varietà Di Grano Duro e Loro Caratteristiche. Quad. Accad. Georgofili VI 1998, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Porceddu, E. Evoluzione Varietale e Problemi Attuali Del Miglioramento Genetico Dei Cereali Vernini. Riv. Agron. 1987, 21, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rivoira, G.; Deidda, M.; Marras, G.F. Evoluzione e Problemi Attuali Della Coltivazione Dei Cereali Vernini. Riv Agron 1987, 21, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Iannelli, P.; Pezzali, M. [Durum Wheat: You Have Worked Hard, but You Have to Insist in This Way to Be Self-Sufficient].[Italian]. Inf. Agrar. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzini, A.; Corazza, L.; D’Egidio, M.G.; Di Fonzo, N.; La Fiandra, D.; Pogna, N.E.; Poma, I. Durum Wheat (Triticum Turgidum Spp. Durum). In Proceedings of the “Italian contribution to plant genetics and breeding”, University of Tuscia. Book prepared at the occasion of the XV Congress of the European Association for Research on Plant Breeding-Eucarpia, 21-25 Sep; 1998; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, A.; Boggini, G. Evoluzione Varietale. Quad. Accad. Dei Georgofili VI 1998, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Strampelli, N. Origini, Sviluppi, Lavori e Risultati. Milano Italy Ist. Naz. Genet. Cerealic. Alfieri Lacroix 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Casale, F. Tre Novità Agrarie. Soc. Ital. Genet. Agrar. 1955, 5, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Laidò, G.; Mangini, G.; Taranto, F.; Gadaleta, A.; Blanco, A.; Cattivelli, L.; Marone, D.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Papa, R.; De Vita, P. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Tetraploid Wheats (Triticum Turgidum L.) Estimated by SSR, DArT and Pedigree Data. Plos One 2013, 8, e67280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, P.; Majo, I. Contributo al Miglioramento Genetico Del Grano Duro. Gen. Agr. 1964, XVII, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pecetti, L.; Boggini, G.; Doust, M.A.; Annicchiarico, P. Performance of Durum Wheat Landrace from Jordan and Morocco in Two Mediterranean Environments (Northern Syria and Sicily). J. Genet. Breed. 1996, 50, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Polano, P. Contributo al Miglioramento Della Produzione Del Grano Duro in Sardegna. Studi Sassar. 1958, VI, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bogyo, T.P.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.T.; Sigurbjörnsson, B.; Bagnara, D. ADAPTATION STUDIES WITH RADIATION-INDUCED DURUM WHEAT MUTANTS; Washington State Univ; Pullman, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Vallega, J. Historical Perspective of Wheat Breeding in Italy. In Proceedings of the 4. FAO/Rockefeller Foundation Wheat Seminar, Tehran, Iran, 21 May 1973; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Vallega, J.; Zitelli, G. New High Yielding Italian Durum Wheat Varieties. Ann. Ist. Sper. Cerealic. Roma Italy 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, A.; Deidda, M. Contributo al Miglioramento Genetico Del Grano Duro. Sementi Elette 1968, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore, G.P. Due Nuove Cultivar Di Grano Duro, 1970.

- Rivoira, G. Alcune Considerazioni Agronomiche Sulle Nuove Cultivars Italiane Di Grano Duro. Genetica agraria 1982, V, 142–192. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandroni, A.; Rusmini, B.; Scalfati, M.C. Influenza Di Specie Del Genere Triticum e Di Altri Generi Nelle Discendenze Di Incroci Interspecifici e Intergenerici per Il Miglioramento Genetico Di Triticum Durum; Instituto nazionale di genetica per la cerealicoltura” N. Strampelli, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Scarascia Mugnozza, G.T. Due Linee Di Frumento Duro Ottenute per Mutazione Radioindotta. Com. Naz. Energ. Nucl. Italy 1968, 4, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzini, A.; Girotto, G. Grani Duri Nell’Italia Centrale. L’Informatore Agrar. 1971, 48, 7335–7340. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzini, A.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.T. A Dominant Short Straw Mutation Induced by Thermal Neutrons in Durum Wheat. Wheat Inf. Serv. 1967, 23, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, T.A. How a Gene from Japan Revolutionized the World of Wheat: CIMMYT’s Quest for Combining Genes to Mitigate Threats to Global Food Security. In Proceedings of the Advances in Wheat Genetics: From Genome to Field: Proceedings of the 12th International Wheat Genetics Symposium, Springer Japan, 2015; pp. 13–20.

- Bozzini, A.; Bagnara, D. Creso, Mida e Tito, Nuovi Grani Duri Del Laboratorio Agricoltura Del CNEN. L’informatore Agrar. 1974, 20, 15869–15871. [Google Scholar]

- Rivoira, G. Risultati Agronomici Conseguiti Dall’attività Collegiale Di Ricerca Del Subprogetto “Frumento Duro”; Enna: 1979; pp. 149–173.

- Porceddu, E.; Spagnoletti Zeuli, P.L.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.T. Genetical Variability in F3 Families from Genetically Distant Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum) Varieties. Genet. Agrar. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; SCARASCIA MUGNOZZA, G. Messapia: Una Nuova Varietà Di Frumento Duro Precoce e Produttiva. Inf. Agrar. 1989, 37, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; Simeone, R.; Resta, P. The Addition of Dasypyrum Villosum (L.) Candargy Chromosomes to Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 1987, 74, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Giorgi, B.; Perrino, P.; Simeone, R. Genetic Resources and Breeding of Durum Wheat Quality. Agric. E Ric. 1991, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Porfiri, O. La ricerca varietale al servizio delle filiere.

- Conforti, P. Un’analisi Delle Ipotesi Di Riduzione Del Sostegno al Grano Duro Nell’Unione Europea e Dei Suoi Effetti in Italia. INEA Work. Pap. 2002, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti, R.; Strampelli, N.; Degani, L.; Raimondi, G.; Wittrich, A. The Wheat Science: The Green Revolution of Nazareno Strampelli. No Title 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, F.; Belocchi, A.; Fornara, M.; Ripa, C.; D’Egidio, M.G. Le varietà di frumento duro in Italia. 2007.

- Reynolds, M.; Langridge, P. Physiological Breeding. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 31, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A.; Edmeades, G.O. Breeding and Cereal Yield Progress. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, S-85–S-98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.J.; Mínguez, M.I. Evolution Not Revolution of Farming Systems Will Best Feed and Green the World. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, F.; Motzo, R.; Pruneddu, G. Trends since 1900 in the Yield Potential of Italian-Bred Durum Wheat Cultivars. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 27, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, P.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Codianni, P.; Fornara, M. Bio-Agronomic Evaluation of Old and Modern Wheat, Spelt and Emmer Genotypes for Low-Input Farming in Mediterranean Environment. Ital. J. Agron. 2007, 2, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Mariani, B.M. La Rete Nazionale Di Prove Di Confronto Tra Varietà Di Frumento Duro: Un Bilancio Dopo Venti Anni. L’informatore Agrar. 1993, 34, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Salis, G.; Motzo, R.; Giunta, F. Salis, G. (2011). Analisi Di Venti Anni Di Prove Di Confronto Tra Varietà Di Frumento Duro (Triticum Turgidum Ssp. Durum L.), Università degli studi di Sassari, Dipartimento di Agraria, Sez. di agronomia, coltivazioni erbacee e genetica, Corso di Laurea in Scienze e Tecnologie agrarie: Sassari, 2011.

- Porceddu, E.; Blanco, A. Evolution of Durum Wheat Breeding in Italy. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Genetics and Breeding of Durum Wheat; Porceddu, E., Qualset, C.O., Damania, A.B., Eds.; 2014; pp. 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, P.; Nicosia, O.L.D.; Nigro, F.; Platani, C.; Riefolo, C.; Di Fonzo, N.; Cattivelli, L. Breeding Progress in Morpho-Physiological, Agronomical and Qualitative Traits of Durum Wheat Cultivars Released in Italy during the 20th Century. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, A.L.; Roncallo, P.F.; Echenique, V. Genetic Gains in Grain Yield and Agronomic Traits of Argentinian Durum Wheat from 1934 to 2015. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, C.; Álvaro, F.; Martos, V.; Ramdani, A.; Isidro, J.; Villegas, D.; García Del Moral, L.F. Genetic Changes in Durum Wheat Yield Components and Associated Traits in Italian and Spanish Varieties during the 20th Century. Euphytica 2007, 155, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancourt-Hulmel, M.; Doussinault, G.; Lecomte, C.; Bérard, P.; Le Buanec, B.; Trottet, M. Genetic Improvement of Agronomic Traits of Winter Wheat Cultivars Released in France from 1946 to 1992. Crop Sci. 2003, 43, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebetzke, G.J.; Ellis, M.H.; Bonnett, D.G.; Condon, A.G.; Falk, D.; Richards, R.A. The Rht13 Dwarfing Gene Reduces Peduncle Length and Plant Height to Increase Grain Number and Yield of Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2011, 124, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Cui, C.; Morgunov, A.; Condon, A.G.; Chen, L.; Hu, Y.-G. GAR Dwarf Gene Rht14 Reduced Plant Height and Affected Agronomic Traits in Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum). Field Crops Res. 2020, 248, 107721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.M.; Spink, J. Predicting Yield Losses Caused by Lodging in Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2012, 137, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.M.; Sterling, M.; Spink, J.H.; Baker, C.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Mooney, S.J.; Tams, A.R.; Ennos, A.R. Understanding and Reducing Lodging in Cereals. Adv. Agron. 2004, 84, 215–269. [Google Scholar]

- Neenan, M.; Spencer-Smith, J.L. An Analysis of the Problem of Lodging with Particular Reference to Wheat and Barley. J. Agric. Sci. 1975, 85, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CROOK, M.J.; Ennos, A.R. The Mechanics of Root Lodging in Winter Wheat, Triticum Aestivum L. J. Exp. Bot. 1993, 44, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, F.; Motzo, R.; Pruneddu, G. Has Long-Term Selection for Yield in Durum Wheat Also Induced Changes in Leaf and Canopy Traits? Field Crops Res. 2008, 106, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, M.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Weightman, R.; Snape, J.W. Identifying Physiological Traits Associated with Improved Drought Resistance in Winter Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2007, 103, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, M.D.; Youssefian, S. Dwarfing Genes in Wheat. Prog. Plant Breed. 1985, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- LeCain, D.R.; Morgan, J.A.; Zerbi, G. Leaf Anatomy and Gas Exchange in Nearly Isogenic Semidwarf and Tall Winter Wheat. Crop Sci. 1989, 29, 1246–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A.; Rees, D.; Sayre, K.D.; Lu, Z.-M.; Condon, A.G.; Saavedra, A.L. Wheat Yield Progress Associated with Higher Stomatal Conductance and Photosynthetic Rate, and Cooler Canopies. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaju, O.; DeSilva, J.; Carvalho, P.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Griffiths, S.; Greenland, A.; Foulkes, M.J. Leaf Photosynthesis and Associations with Grain Yield, Biomass and Nitrogen-Use Efficiency in Landraces, Synthetic-Derived Lines and Cultivars in Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2016, 193, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo-Silva, E.; Andralojc, P.J.; Scales, J.C.; Driever, S.M.; Mead, A.; Lawson, T.; Raines, C.A.; Parry, M.A. Phenotyping of Field-Grown Wheat in the UK Highlights Contribution of Light Response of Photosynthesis and Flag Leaf Longevity to Grain Yield. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 3473–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro, F.; Isidro, J.; Villegas, D.; García Del Moral, L.F.; Royo, C. Breeding Effects on Grain Filling, Biomass Partitioning, and Remobilization in Mediterranean Durum Wheat. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearman, V.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Scott, R.K.; Foulkes, M.J. Physiological Processes Associated with Wheat Yield Progress in the UK. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.A. Crop Improvement for Temperate Australia: Future Opportunities. Field Crops Res. 1991, 26, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorter, R.; Lawn, R.J.; Hammer, G.L. Improving Genotypic Adaptation in Crops–a Role for Breeders, Physiologists and Modellers. Exp. Agric. 1991, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevara, M.G.; Romani, M.; Corbellini, M.; Perenzin, M.; Borghi, B. Evolutionary Trends in Morphological, Physiological, Agronomical and Qualitative Traits of Triticum Aestivum L. Cultivars Bred in Italy since 1900. Eur. J. Agron. 1994, 3, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzo, R.; Giunta, F. The Effect of Breeding on the Phenology of Italian Durum Wheats: From Landraces to Modern Cultivars. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, J.W.; Quarrie, S.A.; Laurie, D.A. Comparative Mapping and Its Use for the Genetic Analysis of Agronomic Characters in Wheat. Euphytica 1996, 89, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worland, A.J. The Influence of Flowering Time Genes on Environmental Adaptability in European Wheats. Euphytica 1996, 89, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.N.; Worland, A.J. Genetic Analysis of Some Flowering Time and Adaptive Traits in Wheat. New Phytol. 1997, 137, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, D.A.; Griffiths, S.; Dunford, R.P.; Christodoulou, V.; Taylor, S.A.; Cockram, J.; Beales, J.; Turner, A. Comparative Genetic Approaches to the Identification of Flowering Time Genes in Temperate Cereals. Field Crops Res. 2004, 90, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slafer, G.A.; Abeledo, L.G.; Miralles, D.J.; Gonzalez, F.G.; Whitechurch, E.M. Photoperiod Sensitivity during Stem Elongation as an Avenue to Raise Potential Yield in Wheat. In Wheat in a Global Environment: Proceedings of the 6th International Wheat Conference, 5–9 June 2000, Budapest, Hungary; Bedö, Z., Láng, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 487–496. ISBN 978-94-017-3674-9. [Google Scholar]

- González, F.G.; Slafer, G.A.; Miralles, D.J. Grain and Floret Number in Response to Photoperiod during Stem Elongation in Fully and Slightly Vernalized Wheats. Field Crops Res. 2003, 81, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, F.; Pruneddu, G.; Motzo, R. Grain Yield and Grain Protein of Old and Modern Durum Wheat Cultivars Grown under Different Cropping Systems. Field Crops Res. 2019, 230, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzo, R.; Giunta, F.; Pruneddu, G. The Response of Rate and Duration of Grain Filling to Long-Term Selection for Yield in Italian Durum Wheats. Crop Pasture Sci. 2010, 61, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, P.L.; Frohberg, R.C. Bruckner, P. L., & Frohberg, R. C. (1987). Rate and Duration of Grain Fill in Spring Wheat 1. Crop Science, 27(3), 451-455. Crop Sci. 1987, 27, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, F.; Mefleh, M.; Pruneddu, G.; Motzo, R. Role of Nitrogen Uptake and Grain Number on the Determination of Grain Nitrogen Content in Old Durum Wheat Cultivars. Agronomy 2020, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderini, D.F.; Torres-León, S.; Slafer, G.A. Consequences of Wheat Breeding on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Yield, Grain Nitrogen and Phosphorus Concentration and Associated Traits. Ann. Bot. 1995, 76, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R. Historical Changes in Harvest Index and Crop Nitrogen Accumulation. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; et al. Pursuing Sustainable Productivity with Millions of Smallholder Farmers. Nature 2018, 555, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raun, W.R.; Johnson, G.V. Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency for Cereal Production. Agron. J. 1999, 91, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, A.; Preiti, G.; Badagliacca, G.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sunseri, F.; Monti, M.; Bacchi, M. Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Durum Wheat Under Different Nitrogen and Water Regimes in the Mediterranean Basin. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 607226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkesford, M.J. Genetic Variation in Traits for Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2627–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, F.; Faure, S.; Dubreuil, P.; Heumez, E.; Beauchêne, K.; Lafarge, S.; Praud, S.; Le Gouis, J. A Multi-Environmental Study of Recent Breeding Progress on Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 3035–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subira, J.; Peña, R.J. Breeding Progress in the Pasta-Making Quality of Durum Wheat Cultivars Released in Italy and Spain during the 20th Century. 2014.

- Motzo, R.; Fois, S.; Giunta, F. Relationship between Grain Yield and Quality of Durum Wheats from Different Eras of Breeding. Euphytica 2004, 140, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, M. Role of Durum Wheat Composition on the Quality of Pasta and Bread. Food 2008, 2, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, N.M.; Gianibelli, M.C.; McCaig, T.N.; Clarke, J.M.; Ames, N.P.; Larroque, O.R.; Dexter, J.E. Relationships between Dough Strength, Polymeric Protein Quantity and Composition for Diverse Durum Wheat Genotypes. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 45, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, F.R.; Clarke, J.M.; Ames, N.A.; Knox, R.E.; Ross, R.J. Gluten Index Compared with SDS-Sedimentation Volume for Early Generation Selection for Gluten Strength in Durum Wheat. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 90, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.A.; Giuliani, M.M.; Giuzio, L.; Vita, P.D.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.R.; Flagella, Z. Differences in Gluten Protein Composition between Old and Modern Durum Wheat Genotypes in Relation to 20th Century Breeding in Italy. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 87, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fois, S.; Schlichting, L.; Marchylo, B.; Dexter, J.; Motzo, R.; Giunta, F. Environmental Conditions Affect Semolina Quality in Durum Wheat ( Triticum Turgidum Ssp. Durum L.) Cultivars with Different Gluten Strength and Gluten Protein Composition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2664–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.A.; Giuliani, M.M.; Giuzio, L.; De Vita, P.; Flagella, Z. Assessment of Grain Protein Composition in Old and Modern Italian Durum Wheat Genotypes. Ital. J. Agron. 2018, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, L.; Mastromatteo, M.; Lecce, L.; Spinelli, S.; Contò, F.; Del Nobile, M.A. Chemical Composition, Sensory and Cooking Quality Evaluation of Durum Wheat Spaghetti Enriched with Pea Flour. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1544–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’egidio, M. G.; Mariani, B. M.; Nardi, S.; Novaro, P.; Cubadda, R. , Chemical and Technological Variables and Their Relationships: A Predictive Equation for Pasta Cooking Quality. Cereal Chem. 673 275-281 1990, 67, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, P.; Pecchioni, N. Considerazioni CREA Sulla Qualità Del Grano Italiano, Con Particolare Riferimento Contenuto Proteico.; Roma, 2016; p. 12.

- Arzani, A. Chapter 7 - Emmer (Triticum Turgidum Ssp. Dicoccum) Flour and Bread. In Flour and Breads and their Fortification in Health and Disease Prevention, 2nd ed.; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 89–98. ISBN 978-0-12-814639-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, R.J.; Trethowan, R.; Pfeiffer, W.H.; Van Ginkel, M. Quality (End-Use) Improvement in Wheat. J. Crop Prod. 2002, 5, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, B.; Prasanna, B.M.; Hellin, J.; Bänziger, M. Crops That Feed the World 6. Past Successes and Future Challenges to the Role Played by Maize in Global Food Security. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.E.; Matsuo, R.R. INFLUENCE OF PROTEIN CONTENT ON SOME DURUM WHEAT QUALITY PARAMETERS. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1977, 57, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacioglu, M. H.; D’appolonia, B. L. Characterization and Utilization of Durum Wheat for Breadmaking. II. Study of Flour Blends and Various Additives. Cereal Chem. 1994, 71, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sissons Mike; Pleming Denise,; Margiotta Benedetta,; D’Egidio Maria Grazia; Lafiandra Domenico Effect of the Introduction of D-Genome Related Gluten Proteins on Durum Wheat Pasta and Bread Making Quality. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 27–37. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C-Y; Shepherd, K. W.; Rathjen, A.J. Improvement of Durum Wheat Pastamaking and Breadmaking Qualities. Cereal Chem 1996, 73, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.F.; Casper, J.; Kiszonas, A.M.; Fuerst, E.P.; Murray, J.; Simeone, M.C.; Lafiandra, D. Soft Kernel Durum Wheat—A New Bakery Ingredient? Cereal Foods World 2015, 60, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, J.D.; Zhang, M.; Cai, X.; Morris, C.F. Molecular and Cytogenetic Characterization of the 5DS–5BS Chromosome Translocation Conditioning Soft Kernel Texture in Durum Wheat. Plant Genome 2017, 10, plantgenome2017.04.0031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlchting, L.M.; Dexter, J.E.; Preston, K.R.; Edwards, N.M.; Marchylo, B.A.; Hucl, P. Quality Characterization of Linesfrom a Cross between Emmer (T. Dicoccum) and Durum(T. Durum)Wheat. In Proceedings of 2nd International Workshop.Durum Wheat and Pasta Quality: Recent Achievements and NewTrends; D’Egidio, M.G., Ed.; Industria Grafica Failli Fausto: Guidonia-Montecelio, Italy, 2003; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Marchylo, B.A.; Dexter, J.E.; Clarke, F.R.; Clarke, J.M.; Preston, K.R. Relationships among Bread-Making Quality, Gluten Strength, Physical Dough Properties, and Pasta Cooking Quality for Some Canadian Durum Wheat Genotypes. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 81, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.T. The Contribution of Italian Wheat Geneticists: From Nazareno Strampelli to Francesco D’Amato. In Proceedings of the International Congress ‘in the Wake of the Double Helix: From the Green Revolution to the Gene Revolution’; Tuberosa, R., Phillips, R.L., Gale, M., Eds.; Avenue Media: Bologna, Italy, 2005; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dinelli, G.; Marotti, I.; Silvestro, R.D.; Bosi, S.; Bregola, V.; Accorsi, M.; Loreto, A.D.; Benedettelli, S.; Ghiselli, L.; Catizone, P. Agronomic, Nutritional and Nutraceutical Aspects of Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.) Cultivars under Low Input Agricultural Management. Ital. J. Agron. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Foulkes, J.; Furbank, R.; Griffiths, S.; King, J.; Murchie, E.; Parry, M.; Slafer, G. Achieving Yield Gains in Wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1799–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.M.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Berry, S. Ideotype Design for Lodging-Resistant Wheat. Euphytica 2007, 154, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, E.; Sears, R.G.; Shroyer, J.P.; Paulsen, G.M. Genetic Gain in Yield Attributes of Winter Wheat in the Great Plains. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.R.; Lilley, J.M.; Trevaskis, B.; Flohr, B.M.; Peake, A.; Fletcher, A.; Zwart, A.B.; Gobbett, D.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Early Sowing Systems Can Boost Australian Wheat Yields despite Recent Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseng, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, E.; Zhang, W. Crop Modeling for Climate Change Impact and Adaptation. In Crop physiology; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 505–546.

- Asseng, S.; Kheir, A.M.S.; Kassie, B.T.; Hoogenboom, G.; Abdelaal, A.I.N.; Haman, D.Z.; Ruane, A.C. Can Egypt Become Self-Sufficient in Wheat? Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 094012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A. Wheat Physiology: A Review of Recent Developments. Crop Pasture Sci. 2011, 62, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rharrabti, Y.; Villegas, D.; García del Moral, L.F.; Aparicio, N.; Elhani, S.; Royo, C. Environmental and Genetic Determination of Protein Content and Grain Yield in Durum Wheat under Mediterranean Conditions. Plant Breed. 2001, 120, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acreche, M.M.; Slafer, G.A. Variation of Grain Nitrogen Content in Relation with Grain Yield in Old and Modern Spanish Wheats Grown under a Wide Range of Agronomic Conditions in a Mediterranean Region. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 147, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, F.; Motzo, R.; Nemeh, A.; Pruneddu, G. Durum Wheat Cultivars Grown in Mediterranean Environments Can Combine High Grain Nitrogen Content with High Grain Yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 136, 126512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogard, M.; Allard, V.; Brancourt-Hulmel, M.; Heumez, E.; Machet, J.-M.; Jeuffroy, M.-H.; Gate, P.; Martre, P.; Le Gouis, J. Deviation from the Grain Protein Concentration–Grain Yield Negative Relationship Is Highly Correlated to Post-Anthesis N Uptake in Winter Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 4303–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, G.; Tang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J. Is Nitrogen Uptake after Anthesis in Wheat Regulated by Sink Size? Field Crops Res. 2000, 68, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, C.; Elias, E.M.; Manthey, F.A.; Carena, M.J. Cereals—Handbook of Plant Breeding. 2009.

- Sciacca, F.; Allegra, M.; Licciardello, S.; Roccuzzo, G.; Torrisi, B.; Virzì, N.; Brambilla, M.; Romano, E.; Palumbo, M. Potential Use of Sicilian Landraces in Biofortification of Modern Durum Wheat Varieties: Evaluation of Caryopsis Micronutrient Concentrations. Cereal Res. Commun. 2018, 46, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Espinosa, N.; Laddomada, B.; Payne, T.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Govindan, V.; Ammar, K.; Ibba, M.I.; Pasqualone, A.; Guzman, C. Nutritional Quality Characterization of a Set of Durum Wheat Landraces from Iran and Mexico. LWT 2020, 124, 109198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes-López, A.M.; Hernandez-Espinosa, N.; Velu, G.; Posadas-Romano, G.; Ordoñez-Villegas, V.M.G.; Crossa, J.; Ammar, K.; Guzmán, C. Variability in Iron, Zinc and Phytic Acid Content in a Worldwide Collection of Commercial Durum Wheat Cultivars and the Effect of Reduced Irrigation on These Traits. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.J.; Loomis, R.S.; Cassman, K.G. Crop Ecology: Productivity and Management in Agricultural Systems; Cambridge University Press, 2011; ISBN 1-139-50032-5. [Google Scholar]

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).