1. Introduction

Globally, countries are adopting the circular economy model to address climate change, maximize resource utilization, and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Domestically, efforts are underway to promote 'circular economy activation' in pursuit of the broader ‘2050 carbon neutrality’ goal of GHG reduction. The circular economy, in stark contrast to the previous linear economic model of mass production, distribution, consumption, and disposal, represents a sustainable concept in which resource use and waste generation are fundamentally reduced throughout the process of production-distribution-consumption-reuse and recycling, allowing for repeated utilization of resources within the economic system [

1,

2].

This transition to a circular economy involves the reusing and recycling of waste that was traditionally disposed of in landfills or incinerated. This practice substantially reduces the burden of waste disposal and raw material extraction, contributing to carbon emissions reduction and the achievement of carbon neutrality objectives. Reduced resource input in the production process not only decreases environmental pollutant emissions but also reduces the ecological disruption caused by resource extraction, thereby contributing to the conservation of biodiversity. From a circular economy perspective, this approach represents a new, limitless recycling technology that is capable of maximizing the efficiency of the resource value chain while addressing the fundamental issues of resource depletion, environmental pollution, and CO

2 emissions (carbon neutrality), and overcoming the limits of available resources for the establishment of a circular economy [

3].

The expanded use of fuel cells is being advocated to enhance resource recycling and energy efficiency and aligns with the core principles of the circular economy. Fuel cells, typically reliant on hydrogen, are versatile energy conversion devices usable in various weather conditions and are favored as zero-carbon emission energy sources in various fields, as they are devoid of carbon within their fuel composition [

4,

5]. The cumulative distribution of fuel cells in South Korea, for example, has increased 69-fold in 2020 compared to 2008, with an annual average growth rate of 42.3% [

6].

Fuel cells generate power when hydrogen fuel is oxidatively separated into hydrogen ions and electrons using a platinum (Pt) catalyst. The hydrogen ions subsequently react with oxygen in the air to produce only water (H

2O) as a by-product [

7,

8]. From a physicochemical perspective, Pt is highly stable and exhibits exceptional catalytic activity in water production, rendering it the most widely used material in fuel cells. However, Pt is classified as a rare metal with limited reserves, rendering it highly susceptible to supply and demand dynamics [

9,

10]. Presently, South Korea produces approximately 0.6 tons of Pt annually from by-products generated in the copper production process. To meet the domestic market demand, however, the country relies primarily on imports. Considering the projected increase in demand, especially in resource-scarce countries such as South Korea, there is a growing need to recycle Pt.

The Pt-containing waste generated in South Korea is either entirely collected for domestic recycling by local companies or exported to overseas processing companies for Pt recovery. Recycling technology for Pt-group metals can be divided into dry and wet methods. Dry methods involve processes such as grinding and reduction, which tend to be complex and carry a risk of explosion when high temperatures are used for metal separation. It can also be challenging to achieve high-purity recovery using dry methods. In contrast, wet methods include ion exchange, reverse osmosis, cementation, and electrowinning. In wet methods, after a pretreatment process, valuable metals are leached with acid or alkali, followed by solvent extraction, chemical precipitation, ion exchange, filtration, and distillation to recover the target metals. Among the wet methods, the electrowinning method, which involves electrochemical reduction to recover soluble precious metals, is known for its highest recovery rate and purity, typically reaching 99.99% [

16].

Furthermore, in 2017, South Korea implemented an integrated environmental management system that established an environmental management framework for businesses that promoted a symbiotic relationship between the environment and the economy [

11]. This system comprehensively analyzes the environmental impact of pollutants and establishes an optimal environmental management strategy framework for businesses, aiming to minimize pollutants throughout their facilities using economically feasible ‘Best Available Techniques’ (BAT) [

12]. To facilitate the application of the BAT, standards for Korean BAT reference documents (K-BREFs) have been disseminated across various business sectors. BAT standards for the nonferrous metal manufacturing industry include techniques related to waste recovery and treatment, aimed at resource recycling and energy efficiency improvement [

13]. This highlights the significance of the circular economy as an essential environmental management approach, emphasizing the need to conserve resources and energy throughout the production process, from raw material inputs to product manufacturing, while concurrently reducing pollutant generation and emissions.

Thus, the disposal of Pt-containing waste in landfills can lead to environmental issues, including soil contamination. Conversely, recycling such waste not only allows for the recovery of valuable metals but also aids in the reduction of various forms of environmental pollution [

14]. This study aims to compare and analyze the environmental effects of recovered Pt (hereafter referred to as 'recycled Pt') sourced from urban mines in contrast to Pt extracted from natural mines (hereafter referred to as 'primary Pt') using a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology. This study addresses an existing gap in environmental assessments related to Pt recycling, thus providing valuable foundational data for research, development, and commercialization within this field.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using the LCA method, following the procedure outlined in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. LCA comprises four main stages, which are goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation. These stages are interrelated and mutually reinforcing [

15].

In the initial goal and scope definition stage, research objectives were selected, and the functional unit, reference flow, system boundaries, allocation rules, assumptions, and limitations of the product or service under study were defined. During the inventory analysis stage, both qualitative and quantitative data on the inputs and outputs within the system that were necessary to perform the functions of the study subject were compiled. The compiled input and output data were linked to a comprehensive database of elementary flow data. A final inventory analysis was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in ISO 14048. In the impact assessment stage, the environmental impact was quantified by multiplying the factors characterized by the environmental burdens identified during the inventory analysis and categorizing them by impact categories to provide a comprehensive view of their effects. During the interpretation stage, the results obtained from both the inventory analysis and impact assessment were evaluated in line with the initial research objectives and scope. This interaction phase facilitated a deeper understanding of the environmental implications and allowed for drawing meaningful conclusions from the data.

2.1. Recycling Process for Platinum-Containing Waste (Waste Solution and Waste catalyst)

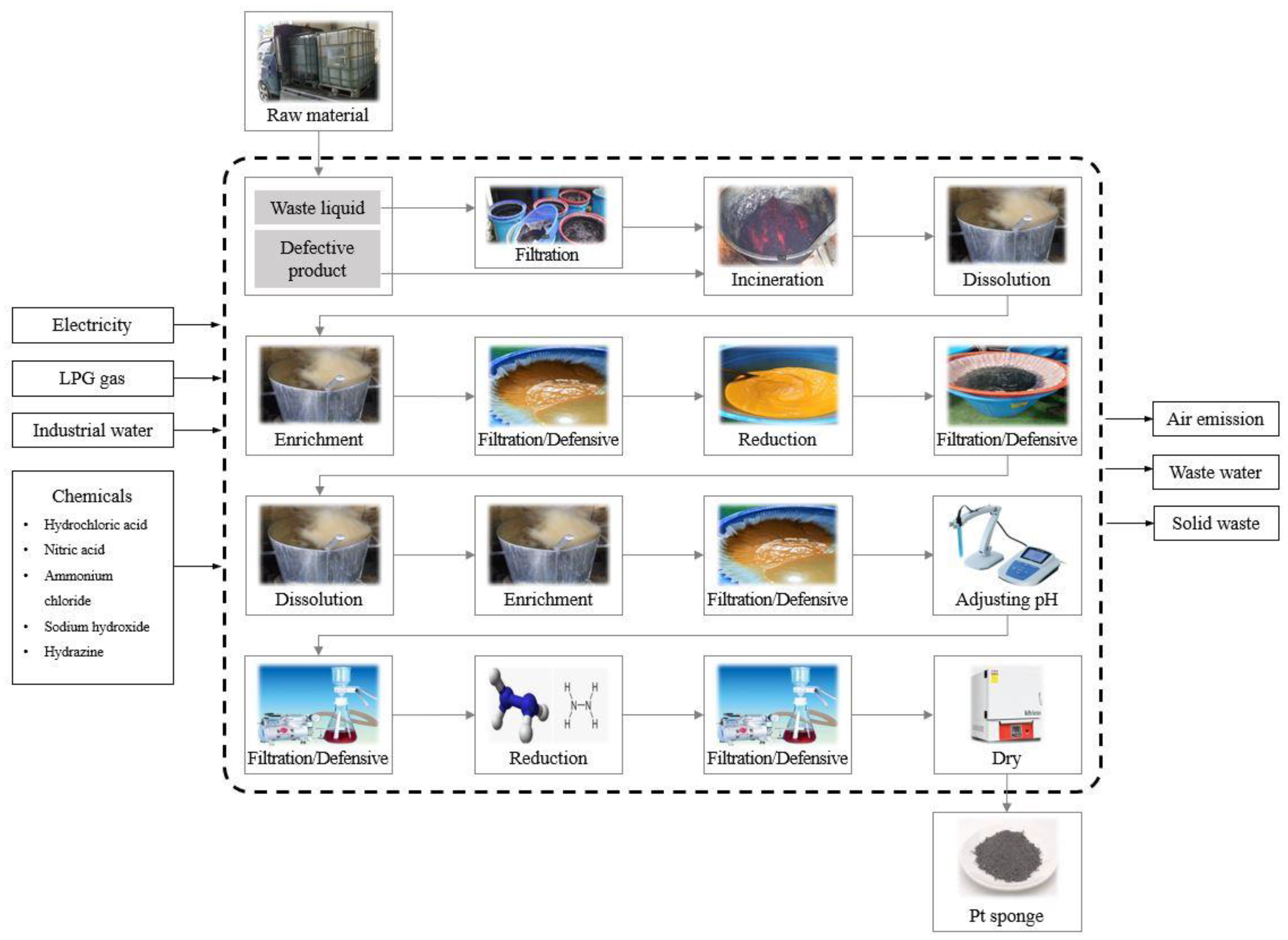

The Pt recycling process focused on in this study used the electrowinning method to recycle Pt, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Waste solutions and waste catalysts discarded in the field were collected and subjected to varying processes such as incineration, dissolution, concentration, precipitation, reduction, and drying to produce Pt with a purity of 99.95 wt%.

Pt-containing waste containing defective products and waste liquid generated from a Pt catalyst manufacturing facility were collected. The liquid waste was filtered to remove impurities, after which the filtered solution and solid waste from the spent catalysts were incinerated at high temperatures. After incineration, the resulting sludge was dissolved in water, and hydrochloric acid was added to the solution during heating to concentrate it. Following concentration, impurities were filtered out, and the solution underwent a precipitation process by adding ammonium chloride to reduce the Pt compounds. The resulting mixture was filtered, and water separation was performed. After filtration, the compound was reintroduced into water through the dissolution, concentration, and filtration processes. The pH of the resulting solution was adjusted using sodium hydroxide, and the impurities were filtered out. A reducing agent was added to the reduction solution and the sponge was filtered and separated after reduction. Finally, the resulting products were dried.

2.2. Goal and Scope Definition

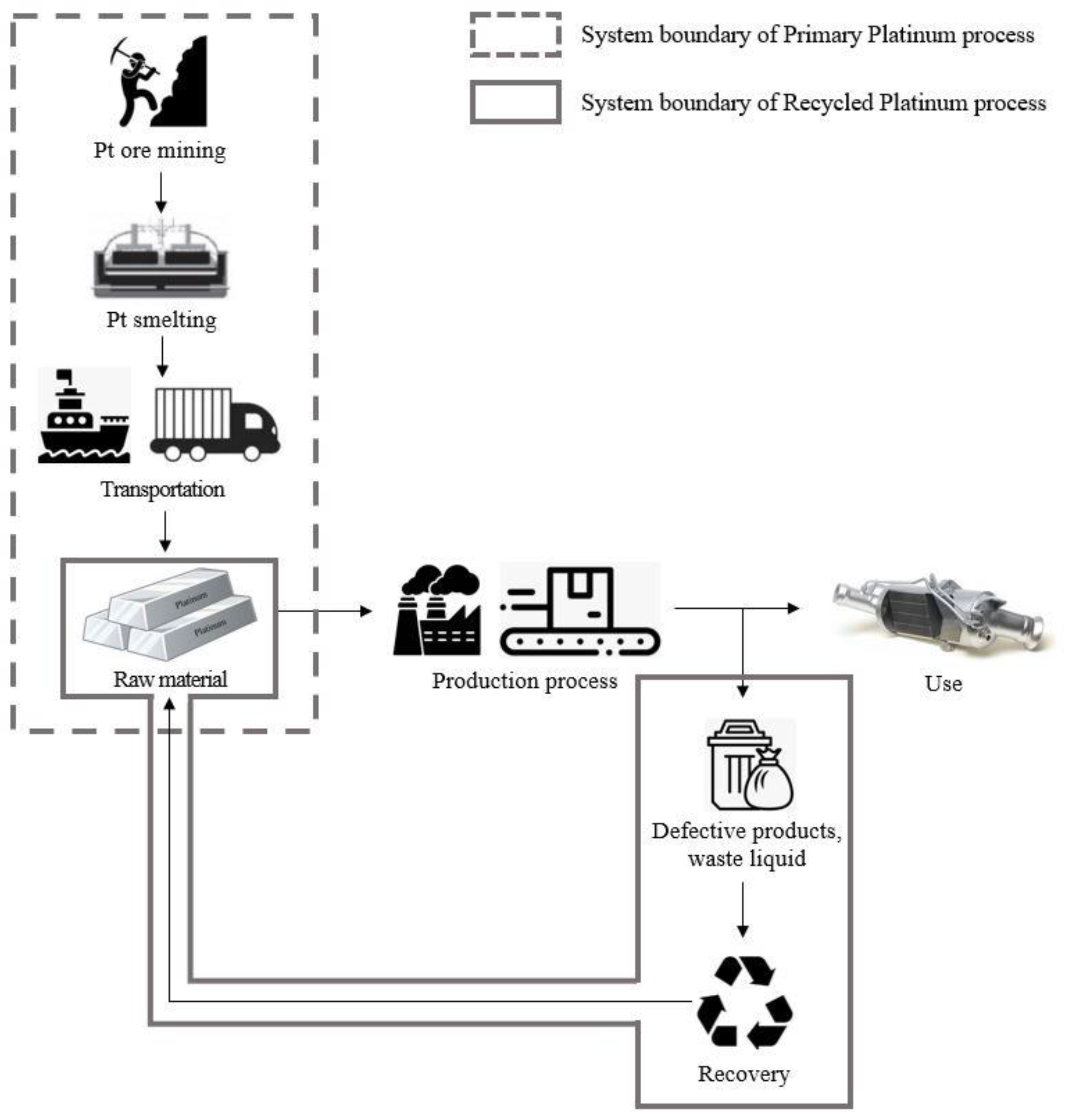

The objective of this LCA study was to assess the environmental impact of primary and recycled Pt and quantify the environmental reduction effects achieved by recycled products compared to primary products. The subject products were defined as primary Pt produced from natural mines and recycled Pt from Pt-containing waste. The system boundary was set as 'Cradle to Gate (CtG),' encompassing raw material acquisition and production up to product manufacturing, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The functional unit was defined as 1 kg of the Pt product. Accordingly, the reference flow for data collection and calculation was '1 kg of Pt.’

Primary Pt was divided into the raw material extraction and transportation stages. Given that South Korea relies predominantly on imports to meet the demand for Pt it is assumed that all Pt is imported, and the transportation stage is thus also included. Recycled Pt is divided into the raw material extraction and recycling stages. Recycled Pt is obtained from the recycling of Pt-containing waste and defective products at 'Company A' in the metropolitan area. To analyze the environmental performance of recycled Pt, it was compared with primary Pt produced from raw materials.

2.3. Life Cycle Inventory Analysis

2.3.1. Data Sources and Calculation

The inventory analysis stage involved data collection, organization, and quantification of input and output materials for unit processes associated with the product system, in accordance with the functional unit. Data sources for primary Pt relied on literature values, given its reliance on imports. In contrast, data for recycled Pt were collected from 'Company A' in the metropolitan area from January to December 2021. The collection of recycled Pt data primarily focused on general information and annual input-output performance items, ensuring reliability through verification with actual field data, as shown in

Table 1.

The inventory analysis for recycled Pt utilized the production information of the subject product to investigate the materials entering the product and quantified them to match the functional unit. In the Pt recycling process, the primary raw material was process waste, and secondary raw materials include hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, hydrazine, and utilities such as water, electricity, and LPG. The outputs include Pt, air, and water emissions. Subsequently, inventory analysis was performed for the inputs and outputs of each process to calculate the environmental impact.

For the raw material acquisition stage of recycled Pt, annual averages were used as the primary raw material, which consisted of process waste (defective products and waste liquid). For the quantity of chemical substances, actual measurement data recorded by the company for the functional units were used to determine the quantity of chemical substances. Emissions were calculated by considering the ratio of emission facility installation permits to the quantity of chemicals used. The emission quantities of air and water pollutants were calculated using the process information.

Electrical power and LPG were used as energy sources in the product-manufacturing stage of recycled Pt. Since the energy consumption of each product is not managed separately, allocation was required to distribute energy usage among the different products. Therefore, in this study, the factory's total electricity consumption data were calculated based on the production quantity of the subject product using Equation (1), based on the energy consumption data collected in 2021. LPG usage was calculated following IPCC guidelines and applied [

17].

The data related to raw materials, utility production, and wastewater treatment for both primary and recycled Pt are presented in

Table 2. Ecoinvent, an overseas Life Cycle Inventory Database (LCI DB), was used for primary Pt and hydrazine, whereas a domestic LCI DB was used for other substances. After data collection and selection of the appropriate LCI DBs, the entire life cycle assessment was conducted using TOTAL software (version 6.5.5).

Given that over 70% of primary Pt produced occurs in South Africa, this study assumes that primary Pt is imported from South Africa [

18]. The transportation stage for primary Pt thus considers transportation from South Africa to the domestic market. The transportation route from South Africa to domestic locations was calculated, and a scenario was created using the Ministry of Environment's shipping transportation LCI DB (overseas container ship (average)). The average transportation distance from South Africa to Incheon Port was calculated to be 13,000 km and was used in the calculation. Additionally, the transportation route from Incheon Port to the recycling company was calculated, and a scenario was established using the Ministry of Environment's road transportation LCI DB (road transportation: less than 1 ton). The transportation distance from Incheon Port to the Pt catalyst company was calculated to be 14 km and was used in the calculation.

2.4. Life Cycle Assessment Results

This study used the TOTAL (version 6.5.5) LCA program developed by the Ministry of Environment. The environmental impacts were quantified in six categories including Abiotic Resource Depletion (ADP), acidification (AP), eutrophication (EP), Global Warming (GWP), Ozone Depletion (ODP), and Photochemical Oxidant Creation (POCP). However, this study primarily focused on the impact assessment for major environmental categories, namely, resource depletion and global warming, due to Pt’s finite availability and its energy-intensive extraction and refining processes. Moreover, energy generation for these processes typically relies on fossil fuels such as coal and oil, leading to significant GHG emissions, such as carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere.

3. Results and Discussion

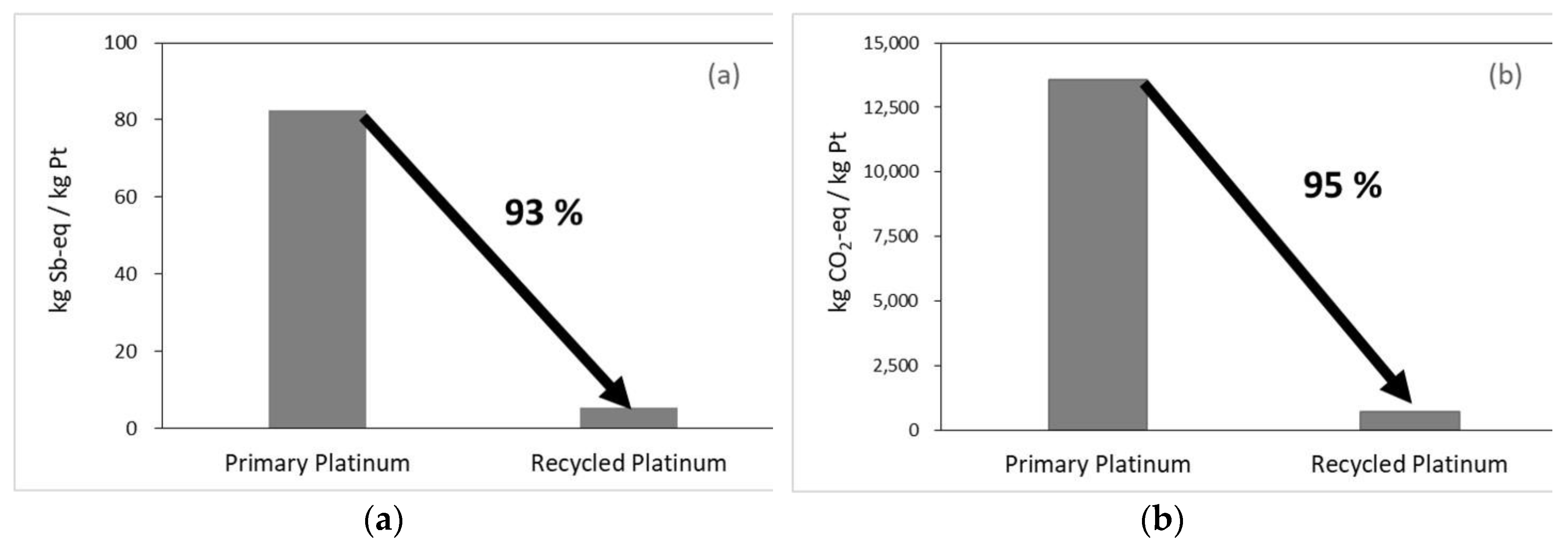

Results for the environmental impact assessment in the resource depletion and global warming categories for 1 kg of Pt, comparing primary and recycled products are presented in

Figure 3. In the resource depletion category, primary Pt was calculated as 8.25E+01 kg Sb-eq./kg, and recycled was calculated as 5.45E+00 kg Sb-eq./kg. The use of recycled Pt resulted in an environmental impact reduction of approximately 93%. In the global warming category, primary Pt was calculated as 1.35E+04 kg CO

2-eq./kg, and recycled was calculated 6.94E+02 kg CO

2-eq./kg. The use of recycled Pt thus resulted in a remarkable reduction in environmental impact of approximately 95%. This is interpreted as a simultaneous improvement in environmental and economic performance owing to reduced GHG emissions and resource saving achieved through Pt recycling.

Upon examining the substances that affect ADP and GWP for 1 kg of primary Pt and recycled Pt, it was found that fuel components such as Crude Oil and Hard Coal had a notable effect on resource depletion. Among GHG emissions, CO

2 and N

2O had the highest emission levels. This can be attributed to the fact that Pt extraction from ore occurs at temperatures of approximately 1,500 °C, requiring substantial quantities of fuels like bituminous coal and electricity to attain such temperatures, resulting in elevated GHG emissions [

19].

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Similar Research Case

The results of this study were compared and analyzed with those of previous studies that evaluated the environmental performance of metal recycling processes using the LCA method. The findings were consistent with prior studies, confirming the environmental benefits of metal recycling. For instance, Shin [

20] employed a CtG assessment method to calculate the resource consumption and GHG emissions associated with palladium (Pd), (one of the Platinum Group Metals), during its recycling and disposal. The analysis showed that recycling 1 kg of Pd resulted in a remarkable reduction of 8,967.17 kg CO

2-eq. in GHG emissions and a decrease of 10.10 kg Sb-eq. in resource consumption. Furthermore, Pd recycling resulted in a substantial 50% reduction of natural resource(Pd).

Kim [

21] conducted a CtG assessment to compare and analyze the environmental impact of the recovery process of silver, a precious metal, from waste plating solutions. As a result of these improvements, the study revealed a noteworthy reduction of approximately 49% (531 kg CO

2-eq.) in GHG emissions and a substantial 67% decrease in resource usage (1.69 kg CO

2-eq.).

Shin [

22] applied the LCA methodology to quantify the environmental impacts of using or not using secondary resources (scrap) in the production of primary processed products for copper and aluminum. The results showed that, for copper, when producing 1 ton of secondary processed products, the environmental impact across all environmental categories was 6.09E+01 person-yr/f.u. when using secondary resources, compared to 7.23E+01 person-yr/f.u. without them, indicating an 18.8% lower environmental impact when using secondary resources. For aluminum, when producing 1 ton of primary processed products, the environmental impact across all environmental categories was 2.34E+02 person-yr/f.u. when using secondary resources and 3.01E+02 person-yr/f.u. without them, demonstrating a 28.4% reduction in environmental impact when secondary resources were used.

Comprehensive findings from previous studies on metal recycling revealed a reduction in the environmental impact of metal recycling. Specifically, there was a 50% reduction in palladium, an approximately 49% reduction in GHG emissions, a 67% reduction in resource usage for silver, an approximately 20% reduction in the case of copper, and an approximately 30% reduction for aluminum. These results confirm the environmental benefits of metal recycling.

When comparing the environmental reduction effects of this study with those of previous studies, the higher efficacy in this study could be attributed to differences in the comparison subjects. In the case of palladium, the comparison was between the disposal and recycling processes [

20], while for silver, the comparison was between an existing recycling process and an improved one [

21]. In the instances of copper and aluminum, the comparison was between production from ore versus production from ore and secondary resources (scrap) [

22]. In contrast, this study compares natural resources such as ores with Pt-containing waste materials. Consequently, the effects of resource saving and GHG reduction in this study appear to be substantially greater than those reported by Shin [

20], Kim [

21], and Shin [

22]. Pt refining from ore requires a substantial amount of resources and energy, whereas the waste materials considered in this study required far less energy for Pt extraction than the ore. This indicates a relatively substantial environmental reduction effect compared to natural ore resources.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a quantitative analysis of the environmental performance of both primary and recycled Pt products was conducted using LCA. Based on this analysis, the following conclusions were drawn:

The LCA analysis revealed a remarkable environmental advantage for Pt recycled from Pt-containing waste materials, showcasing a noteworthy 93% reduction in resource consumption and an equally substantial 95% reduction in GHG emissions when compared to Pt derived from natural ore mines. The primary environmental impact factors also showed that the reduced input of new resources led to the most substantial decrease in the environmental impact from the perspective of resource scarcity. Additionally, during the product manufacturing phase, the environmental impact of primary Pt production exceeded that of recycled Pt, mainly due to the higher electricity consumption during primary product manufacturing.

Traditional Pt mining, which involves high-temperature smelting and refining processes, relies heavily on fossil fuels and electricity input, consequently generating substantial GHG emissions. In stark contrast, the recycling process involves the extraction of Pt from Pt-containing waste materials rather than from ores, resulting in relatively lower energy consumption. As a result, the reduced reliance on fuel for achieving high temperatures during the recycling process contributes to its lower environmental impact compared with new Pt production.

Pt, being a rare metal with limited resource extraction capabilities, demands innovative solutions for resource conservation. Domestic recycling technologies are a significant avenue for overcoming these limitations and contributing to the efforts of energy-poor nations. With the anticipated surge in Pt demand driven by the burgeoning hydrogen economy and increased market needs, efforts to improve Pt recycling rates will be necessary in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H., T.K., H.K. and Y.H.; methodology H.H., T.K. and Y.H.; validation H.H., T.K., H.K. and Y.H.; data curation, H.H. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—review and editing, H.H., Y.H. and H.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Environment, National Institute of Environment Research, Grant Number NIER-2021-01-02-034.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ministry of Environment. The Ministry of Environment is working to spread the circular economy to industries: South of Korea, 2023.

- Ministry of Environment. The National Assembly passed the Act on the Promotion of Circular Economy and Social Transformation: South of Korea, 2022.

- Kim, B.J.; Chae, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Yoo, K.K. Oversea Production Status of Gold, Silver, Platinum and Palladium from Scrap. Resour Recycl. 2018, 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, L.; Lupsea. M.; Mandil. G.; Svecova, L.; Yhivel, P-X.; Laforest, V. Environmental assessment of proton exchange membrane fuel cell platinum catalyst recycling. J Clean Prod. 2017, 142, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, C.; Zincir, B. Environmental and economical assessment of altercative marine fuels. J Clean Prod. 2016, 113, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Choi, G.B.; Yeom, S.C. Fuel cell market and industry trends and implications. GTC BRIEF. 2022, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H.; Choi, J.Y. Research Status of Hydrogen Fuel Cell System Based on Hydrogen Electric Vehicle, J Energy Eng. 2020, 29, 26-34.

- Ham, K.H.; Chung, S.K.; Lee, J.Y. A Comprehensive Review of PEMFC Durability Test Protocol of Pt Catalyst and MEA. Appl Chem Eng. 2019, 30, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, I.J.; Sohn, H.S. Smelting of Platinum Group Metals and Recycling of Spent Catalyst. Resour Recycl, 30. [CrossRef]

- Hodnik, N.; Baldizzone, C.; Polymeros, G.; Geiger, S., Grote, J-P.; Cherevko, S.; Mingers, A.; Zeradjanin, A.; Mayrhofer, K.J. Platinum recycling going green via induced surface potential alteration enabling fast and efficient dissolution, Nat Commun, 2016. www.nature.com/naturecommunications. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. Act on Integrated Management of Environmental Pollution Facilities. 2021. Available online. https://www.law.go.kr.

- Kim, G.; Kang, P.-G.; Kim, E.; Seo, K. Application of Best Available Techniques to Remove Air and Water Pollutants from Textile Dyeing and Finishing in South Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2209 https:// doiorg/103390/su14042209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, National Institute of Environmental Research. Standards on Best Available Techniques for Environmental Pollution Prevention and Integrated Management of Nonferrous Metal Manufacturing Industry. Available online: https://ieps.nier.go.kr/web/board/5/404/?page=2&pMENUMST_ID=95 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Kim, B.J.; Chae, S. J.; Kim, J.S.; Yoo, K.K. Oversea Production Status of Gold, Silver, Platinum and Palladium from Scrap. Resour Recycl, 2018; 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 14040, in Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework, 2011, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kim, Y-S. Recovery of Valuable Metal from e-Wasted Electronic Devices. J Kor Inst Surf Eng. 2016, 49, 477-485. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, 2006. 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. 2006 IPCC Guidel. 3. Natl. Greenh. Gas Invent., pp. 1–40.

- Bloxham, L.; Brown, S.; Cole, L.; Cowley, A.; Fujita, M.; Girardot, N.; Jiang, J.; Raithatha, R.; Ryan, M.; Tang, B.; Wang, A. PGM market report, 2023, https://matthey.com/pgm-market-report-2022.

- Bossi. T.; Gediga. J. The Environmental Profile of Platinum Group Metals. Johnson Matthey Technol Rev. 2017, 61, 111-121. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kang, H.Y. Analysis of Resource and GHG Reduction by Recycling Palladium in Plated Spent Catalyst Solution. Resour Recycl. 2021, 30, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwang, Y.W.; Kwon, T.K. Life Cycle Environmental Analysis of Valuable Metal(Ag) Recovery Process in Plating Waste Water. Resour Recycl. 2023, 32, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.C.; Hwang, Y.W.; Moon, J.Y.; Kong, C.H. An Environmental Evaluation of Copper and Aluminum Metal Resources Circulation by Life Cycle Assessment. J Kor Soc Environ Engin. 2014, 36, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).