Introduction

Pneumatosis intestinalis is a medical condition with the air within the walls of the bowel [

1]. It can be symptomatic or asymptomatic depending on the underlying cause. It can be benign and resolve on its own or can present with other medical conditions like bowel infection, bowel obstruction, autoimmune disorders like Crohn’s disease, etc., [

2]. It occurs due to increased pressure and hyperperistalsis which forces air to enter bowel walls [

3]. It commonly occurs at the submucosal or subserosa layer of the gastrointestinal tract. Air can be present either continuously or by forming cysts. It is also known as Pneumatosis Cystoid Intestinalis. Pneumocystis Intestinalis is commonly present with symptoms like abdominal pain, abdominal distention, fever, nausea, and vomiting. It can be diagnosed by computed tomography (CT scan), ultrasonography (USG), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It can resolve on its own or require surgical procedures like resection anastomosis.

Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis occurs due to blockage of blood flow via a clot formed within the artery [

4]. SMA arises from the abdominal aorta and it is the major blood supply of the small intestine along with a small part of the large intestine. It supplies the midgut from the second part of the duodenum to the splenic flexure of the large intestine [

5]. Thrombosis of any branch of SMA can cause ischemia of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or even cecum. Most commonly it causes jejunal ischemia. Superior Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis can be caused due to atherosclerosis, vasculitis, or emboli dislodging from the other thrombus. It has similar symptoms to Pneumatosis Intestinalis like abdominal pain, fever, tenderness, reduced bowel sounds, or nausea-vomiting. It can also be diagnosed via computed tomography (CT scan) or MR angiography. Both conditions can be distinguished by radiological studies and laboratory testing.

Case Presentation

Presenting a Case Report of a 67-year-old male presented to the hospital with the complaint of generalized abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, obstipation, and postprandial fullness for 5 days. The patient was asymptomatic 5 days before the abdominal pain started. It was insidious in onset with gradually increasing in severity from mild to moderate causing progressive and intermittent colicky pain. It is aggravated by ingesting food and water and is not relieved by medication. It is associated with 3 episodes of nausea and vomiting in 5 days. The patient vomited around 50 cc in volume, containing ingested food particles, and was foul smelling. It is also associated with fever for 3 days which is relieved by medication and obstipation. The patient has not passed stool or flatus for 5 days.

Past History

The patient has a history of dental infection for 10 days. No history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension. Past operative history of bilateral cataract around 40 years ago

Personal History

The patient has a history of addiction to alcohol 250 cc/day for 30 years has stopped for 2 years, has been smoking 1 pack/day for 30 years, and stopped for 1 week.

Physical Examination

Physical examination showed a temperature of 99.6 F, pulse rate of 86/min, blood pressure of 110/82, SpO2 96% on room air, and RBS of 106 mg/dl. Icterus is present over the skin and upper sclera with no other signs of pallor, clubbing, cyanosis, edema, and lymphadenopathy. Respiratory examination showed a respiratory rate of 18/min and bilateral air entry was present and clear but reduced. S1S2 were present on cardiovascular examination. The patient was oriented and responding to verbal commands.

On Per Abdominal inspection, Inspection revealed the abdomen was globular with normal shape and contour and the umbilicus was centrally placed and inverted. There was no visible sinus, scar, fistula, visible lump, or dilated veins. Visible peristalsis, pulsatile movements, and pigmentation were also not seen. All hernial sites appeared normal with no impulse to cough. On palpation, all the findings of inspections were confirmed. On superficial palpation, the abdomen was distended, non-warm, and non-non-tender with no swelling. On deep palpation, there was no organomegaly, deep tenderness, rebound tenderness, or guarding but rigidity was present. On percussion, normal tympanic notes were heard over the abdomen except for the liver and spleen where dull notes were heard. On auscultation normal peristaltic bowel sounds were heard in the right paraumbilical, right, and left lumbar region 5 times/min. No abdominal bruit was present.

Per Rectal Examination, there are no external hemorrhoids, skin tags, scars, fissures, fistula, or sinus present. The anal tone was found normal on deep rectal examination. Stool stains were present and there was no active bleeding.

Radiological Examination

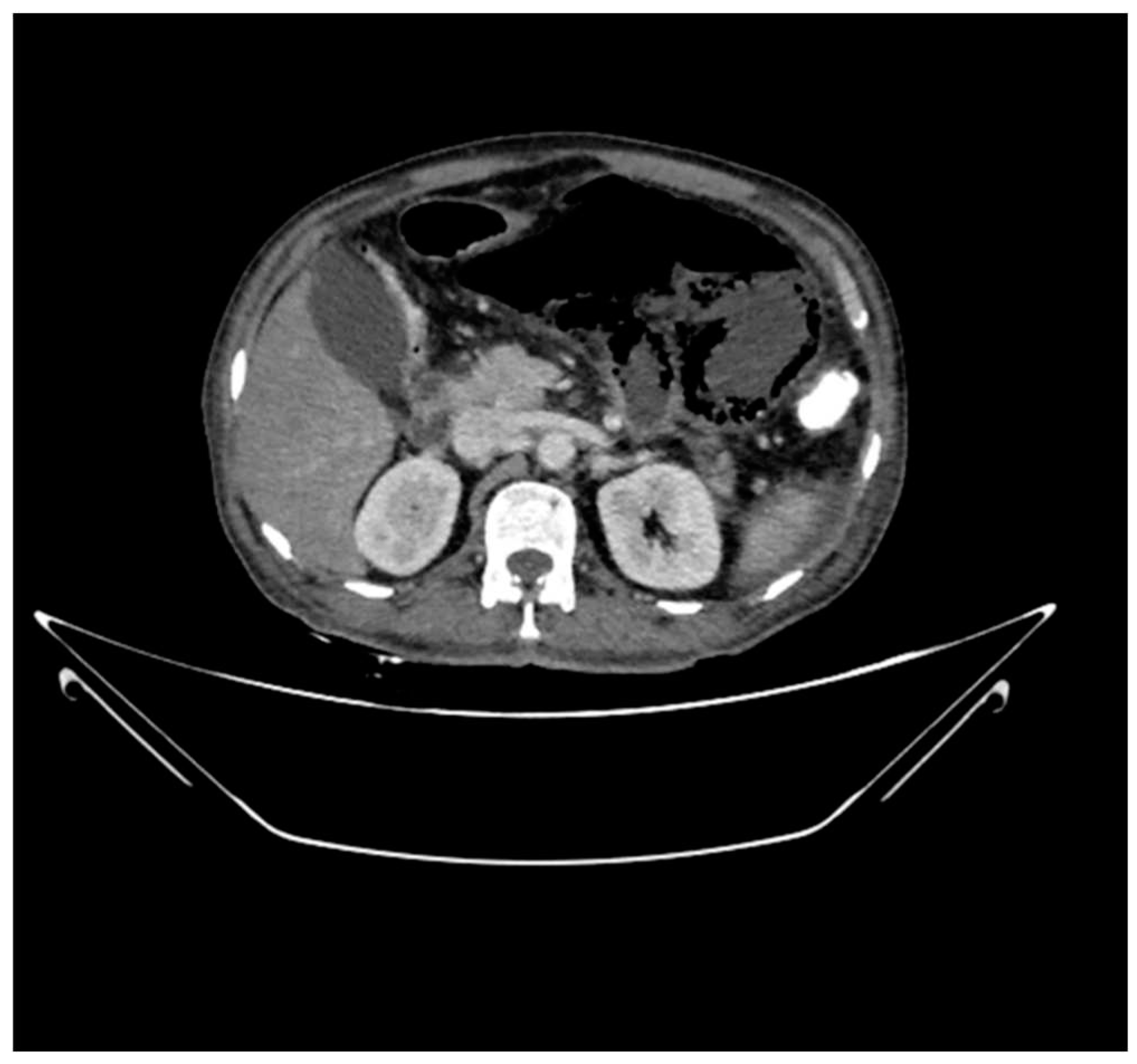

On MDCT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis with oral, per-rectal and IV contrast using 60 ml of non-ionic contrast showed circumferential air within the walls of proximal jejunal loops beyond the duodenal-jejunal junction Contiguous axial, coronal, and sagittal images were obtained. It gives the suggestive diagnosis of Pneumatosis intestinalis with a barely appreciable wall of the bowel in the left hypochondriac region. One of the loops appears dilated due to the presence of air within the walls with a maximum diameter of 6 cm. There is free fluid with fat adjacent to it. The gall bladder is distended with hyperdense sludge. A complete contrast filling defect is noted in the proximal superior mesenteric artery for a segment of 2.7 cm from its origin which distally appears patent.

Figure 1.

Circumferential air within the walls of Jejunal loops.

Figure 1.

Circumferential air within the walls of Jejunal loops.

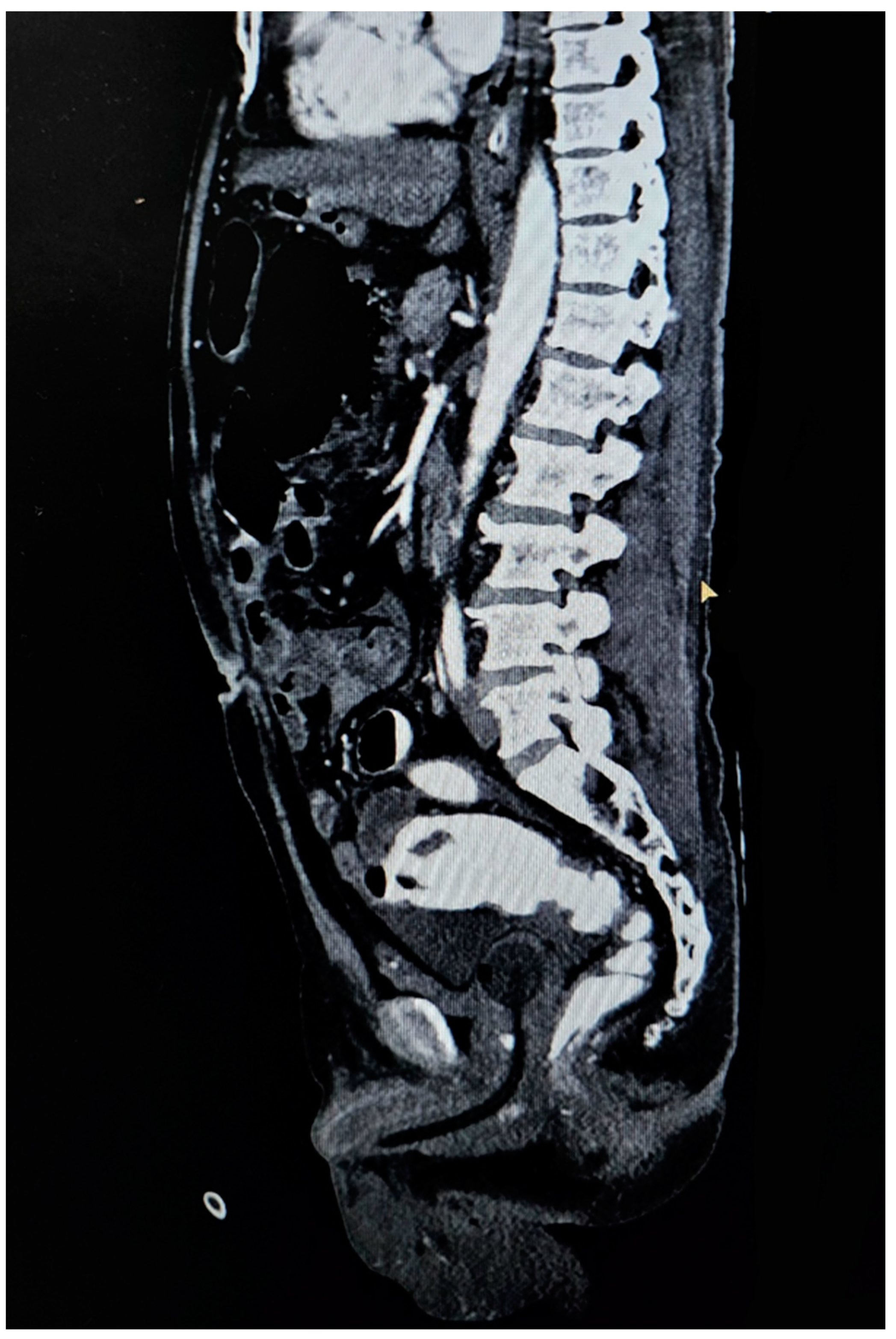

Calcified atheromatous plaques are noted at the origin of the celiac trunk for a segment of 4 mm and at the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery for a segment of 5 mm from their origins respectively causing severe luminal narrowing which distally appears patent.

Figure 2.

Thrombus in Superior Mesenteric Artery in Initial Segment

Figure 2.

Thrombus in Superior Mesenteric Artery in Initial Segment

The above CT scan findings are suggestive of a few proximal jejunal loops beyond the duodeno-jejunal junction showing circumferential air within the wall giving evidence of Pneumatosis Intestinalis with barely appreciable wall. One of the loops appears air-filled and distended with surrounding fluid in the left hypochondriac region with evidence of proximal superior mesenteric artery thrombosis causing jejunal ischemia.

X-ray abdomen showed few abnormal air-fluid levels in the periumbilical region. The bilateral hemidiaphragm is normal in position and there is no evidence of abnormal gas under the diaphragm. No abnormal gas patterns are seen within bowel loops.

Diagnosis

From the above-mentioned radiological findings, laboratory reports, and signs and symptoms, a diagnosis of Superior Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis along with Pneumatosis intestinalis was made.

Treatment

Thrombectomy was performed for the Superior Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Pneumatosis intestinalis was treated with the help of supportive treatment.

Follow Up

Patient follow-up was taken according to the treatment and gradual improvement was seen over the period. Over the year the patient fully recovered with normal appetite and no more complaints of fever or abdominal pain.

Discussion

Pneumatosis intestinalis is a medical condition associated with the presence of gas within the intestinal walls. This leads to a thicker and more prominent wall appearance in CT scans and X-rays. It can be a benign condition but can also lead to a life-threatening condition depending on its cause and severity [

6]. Pneumatosis Intestinalis is also known as Pneumatosis Cystoid Intestinalis. It is a nitrogen-containing cyst formation within the submucosa and subserosa of the intestinal wall [

7]. Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis is a serious medical condition characterized by clot formation within the artery. Most commonly it is caused by atherosclerosis. SMA is the major branch supplying the midgut and it arises from the abdominal aorta. Blockage of this artery compromises its blood supply and causes ischemia of the gut walls. It is a life-threatening condition and its manifestations include abdominal pain, nausea-vomiting, and abdominal tenderness.

Pneumatosis Intestinalis is caused due to increased intraluminal pressure which forces nitrogen into the layers of bowel walls leading to increased wall thickness and obstipation. It can occur anywhere throughout the gastrointestinal tract but most commonly it is seen within the jejunal walls between the submucosal and subserosa layers [

8]. The gastrointestinal tract has four layers, which are from inside to out, mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa layers [

9]. Pneumatosis intestinalis occurs within the submucosal layer. Gas accumulates in the connective tissue of the submucosa. The submucosal layer contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerve fibers. Its occurrence is equal among both sexes and it is seen within different age groups.

There are two types of Pneumatosis Intestinalis, i.e., Primary and Secondary Pneumatosis Intestinalis [

10]. Primary Pneumatosis intestinalis is generally a benign condition and not associated with any medical condition. It is asymptomatic and resolves on its own. It is most commonly seen in infants. Secondary Pneumatosis intestinalis is generally associated with a medical condition and is seen in adults [

11]. It is more serious and presents with symptoms like fever, colicky pain, nausea, vomiting, and obstipation. It can be associated with gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal conditions like tuberculosis of ileum/jejunum, Crohn’s disease, radiation enteritis, intestinal obstruction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autoimmune disorders, or iatrogenic causes like blunt abdominal trauma barium enema, endoscopy, etc. Symptoms of Pneumatosis intestinalis depend on the underlying cause and the extent of gas within the intestinal wall. Some of the common symptoms are abdominal pain, bloating, obstipation, nausea-vomiting, and fever if infection is present. It can get complicated due to intestinal obstruction, hemorrhage, and perforation.

Radiological tools such as computed tomography (CT scan), x-rays, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used for the diagnosis of Pneumatosis intestinalis. It shows thickened walls of the intestines. Computed tomography (CT scan) is the most sensitive method as it can also detect the cause of the Pneumatosis Intestinalis [

12]. Additional tests performed are endoscopy, biopsy, and small bowel enema.

Treatment depends on the type and underlying cause of Pneumatosis Intestinalis. If it is Primary Pneumatosis Intestinalis then it is mostly benign and asymptomatic. In most cases, it resolves on its own and only close observation is enough. In Secondary Pneumatosis intestinalis, it is necessary to treat its underlying cause along with resection anastomosis and stricturoplasty.

Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis is caused due to atherosclerosis, embolization, vasculitis, or other hypercoagulable states like polycythemia vera or autoimmune disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis. Atherosclerosis is a condition in which plaque is formed within the artery lumen and narrows it, compromising the blood supply. Vasculitis is an inflammatory condition affecting blood vessels that can lead to thrombus formation. Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis condition can get complicated further by bowel ischemia if not properly treated. It can also lead to peritonitis and sepsis. Symptoms of Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis are mostly abdominal pain and tenderness. Infarcted areas can also get infected and cause fever. Nausea-vomiting are the common symptoms along with loss of appetite.

Diagnosis of Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis can also be made by imaging studies like computed tomography (CT scan), ultrasonography, and MR angiography [

13]. CT scan and ultrasonography can identify the thrombus and MR angiography helps to locate its exact position. Blood tests show elevated lactate levels which may indicate tissue ischemia. Doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive test that can sometimes be used to assess blood flow in the mesenteric arteries.

Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis can be treated with the help of medications like Heparin and Warfarin (Anticoagulants) [

14]. In serious cases, invasive procedures like thrombectomy or angioplasty may be performed to restore blood flow. Supportive care like intravenous fluid and nutritional support may be required in cases of bowel ischemia.

Conclusion

This case is about a 67-year-old male with presented with generalized abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting, which after investigation was diagnosed with Pneumatosis Intestinalis and Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis causing jejunal necrosis. Pneumatosis Intestinalis is a medical condition where air within the bowel walls is present, it can be benign or secondary to other underlying pathology. In this scenario, it was associated with Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis, which can lead to bowel ischemia and may be threatening. The patient was treated by thrombectomy for Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Thrombosis, and supportive treatment was given for Pneumatosis intestinalis. The complete approach, including clinical evaluation, laboratory investigations, and radiological studies, led to an accurate diagnosis of this condition, and prompt treatment was given for better patient recovery. Regular follow-ups ensured sustained improvement while emphasizing the significance of a multilevel approach in managing such medical conditions.

Laboratory Investigation

| CBC |

OBSERVED VALUE |

UNITS |

REFERENCE RANGE |

| HEMOGLOBIN |

8.0 |

mg/dl |

12–18 mg/dL |

| WBC |

22.34 |

kU/L |

5.2-12.4 U/L |

| RBC |

2.58 |

10^6/ul |

4.5-5.5 10^6/ul |

| MCV |

94.6 |

fl |

83-101 fl |

| MCH |

30.8 |

Pg/ml |

27-32 Pg/ml |

| MCHC |

32.5 |

g/dl |

31.5-34.5 g/dl |

| RDW |

15.3 |

% |

11.5-14.5 % |

| PLATELET |

39 |

kU/L |

130-400 kU/L |

| MPV |

10.6 |

fl |

7.2-11.1 fl |

| NEUTROPHILS |

94 |

% |

49-74 % |

| LYMPHOCYTES |

03 |

% |

26-46 % |

| MONOCYTES |

03 |

% |

2-12 % |

| EOSINOPHILS |

00 |

% |

0-5 % |

| |

|

|

|

| BASOPHILS |

00 |

% |

0-2 % |

| LFT |

OBSERVED VALUE |

UNITS |

REFERENCE RANGE |

| SGPT (ALT) |

11 |

units/litre |

10-49 units/liter |

| SGOT (AST) |

23 |

units/litre |

0-34 units/liter |

| ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE |

70 |

units/litre |

45-129 units/liter |

| TOTAL BILIRUBIN |

2.41 |

mg/dl |

0.3-1.2 mg/dl |

| DIRECT BILIRUBIN |

1.62 |

mg/dl |

0-0.2 mg/dl |

| INDIRECT BILIRUBIN |

0.79 |

mg/dl |

|

| PROTEIN SERUM |

4.20 |

g/dl |

5.7-8.2 g/dl |

| ALBUMIN SERUM |

1.84 |

g/dl |

3.2-4.8 g/dl |

| GLOBULIN SERUM |

2.36 |

g/dl |

2-3.5 g/dl |

| PROTEIN A/G RATIO SERUM |

0.78 |

|

1.5-2.5 |

| RFT |

OBSERVED VALUE |

UNITS |

REFERENCE RANGE |

| BLOOD UREA |

24.6 |

mg/dl |

19.3-49.2 mg/dl |

| CREATININE |

0.34 |

mg/dl |

0.74-1.35 mg/dL |

| SODIUM |

144 |

mmol/L |

135-145 mmol/L |

| POTASSIUM |

3.40 |

mmol/L |

3.5-5.5 mmol/L |

| CHLORIDE |

107 |

mmol/L |

99-109 mmol/L |

Funding and Sponsorship

None of the authors have a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

Ethical Statement

Being a case report study, there were no ethical issues and the IRB was notified about the topic and the case. Still, no formal permission was required as this was a record-based case report. Permission from the patient for the article has been acquired and it has been made sure that their information or identity is not disclosed.

Patient Consent

The patient in the study was provided with detailed information about the purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and confidentiality measures associated with the research. The patient was given ample time to review the informed consent, ask questions, and make an informed decision regarding their participation. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient before their involvement in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- H. Ogul et al., “Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis: An Unusual Cause of Intestinal Ischemia and Pneumoperitoneum,” Int Surg, vol. 100, no. 2, pp. 221–224, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Takase, N. Akuzawa, H. Naitoh, and J. Aoki, “Pneumatosis intestinalis with a benign clinical course: a report of two cases,” BMC Res Notes, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 319, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Devgun and H. Hassan, “Pneumatosis Cystoides intestinalis: A Rare Benign Cause of Pneumoperitoneum,” Case Rep Radiol, vol. 2013, pp. 1–3, 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. Franca, M. E. Shaydakov, and J. Kosove, Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis. 2023.

- H. Shaikh, C. J. Wehrle, and A. Khorasani-Zadeh, Anatomy, Abdomen, and Pelvis: Superior Mesenteric Artery. 2023.

- G. Kang, “Benign pneumatosis intestinalis: Dilemma for primary care clinicians.,” Can Fam Physician, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 766–768, Oct. 2017.

- S. Galandiuk and V. W. Fazio, “Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis,” Dis Colon Rectum, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 358–363, May 1986. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, C.-T. Hsieh, and J.-M. Sun, “Pneumatosis intestinalis after systemic chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A case report,” World J Clin Cases, vol. 10, no. 16, pp. 5337–5342, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D.-H. Liao, J.-B. Zhao, and H. Gregersen, “Gastrointestinal tract modeling in health and disease,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 169, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Im and F. Anjum, Pneumatosis Intestinalis. 2023.

- G. Tropeano et al., “The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult. A surgical dilemma,” World J Gastrointest Surg, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 553–565, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Kelvin, M. Korobkin, R. F. Rauch, R. P. Rice, and P. M. Silverman, “Computed Tomography of Pneumatosis intestinalis,” J Comput Assist Tomogr, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 276, Apr. 1984. [CrossRef]

- E. Sulger, H. S. Dhaliwal, A. Goyal, and L. Gonzalez, Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis. 2023.

- E. Franca, M. E. Shaydakov, and J. Kosove, Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).