Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd El-Aziz T.M; Stockand J.D. Recent progress and challenges in drug development against COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) - an update on the status. Infect Genet Evol. 2020; 83:104327. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A.; Tiwari S.; Deb M.K.; Marty J.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020, 56(2):106054. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty S.K.; Satapathy A.; Naidu M.M.; Mukhopadhyay S.; Sharma S.; Barton L.M.; Stroberg E.; Duval E.J.; Pradhan D.; Tzankov A.; Parwani A.V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) - anatomic pathology perspective on current knowledge. Diagn Pathol. 2020, 15(1):103.

- Chatterjee P.; Nagi N.; Agarwal A.; Das B.; Banerjee S.; Sarkar S.; Gupta N.; Gangakhedkar R.R. The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A review of the current evidence. Indian J Med Res. 2020, 151(2&3):147-159. [CrossRef]

- Arshad Ali S.; Baloch M.; Ahmed N.; Arshad Ali A.; Iqbal A. The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-An emerging global health threat. J Infect Public Health. 2020, 13(4):644-646. [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi C.; Alsafi Z.; O'Neill N.; Khan M.; Kerwan A.; Al-Jabir A.; Iosifidis C.; Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020, 76:71-76. [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta D.; Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91(1):157-160. [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu A.; Okorie C.; Marinkovic A.; Patidar R.; Younis K.; Desai P.; Hosein Z.; Padda I.; Mangat J.; Altaf M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020, 2(8):1069-1076. [CrossRef]

- Bajgain K.T.; Badal S.; Bajgain B.B.; Santana M.J.; Prevalence of comorbidities among individuals with COVID-19: A rapid review of current literature. Am J Infect Control. 2021, 49(2):238-246. [CrossRef]

- Mi J.; Zhong W.; Huang C.; Zhang W.; Tan L.; Ding L. Gender, age and comorbidities as the main prognostic factors in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Transl Res. 2020, 12(10):6537-6548.

- Varikasuvu S.R.; Dutt N.; Thangappazham B.; Varshney S. Diabetes and COVID-19: A pooled analysis related to disease severity and mortality. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021, 15(1):24-27. [CrossRef]

- Lippi G.; Wong J.; Henry B.M. Hypertension in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020, 130(4):304-309.

- Cai R.; Zhang J.; Zhu Y.; Liu L.; Liu Y.; He Q. Mortality in chronic kidney disease patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021, 53(8):1623-1629. [CrossRef]

- Menon T.; Gandhi S.A.Q.; Tariq W.; Sharma R.; Sardar S.; Arshad A.M.; Adhikari R.; Ata F.; Kataria S.; Singh R. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cureus. 2021, 13(4):e14279. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z.H.; Tang Y.; Cheng Q. Diabetes increases the mortality of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58(2):139-144. [CrossRef]

- Pranata R.; Lim M.A.; Huang I.; Raharjo S.B., Lukito A.A. Hypertension is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2020, 21(2):1470320320926899. [CrossRef]

- Jager K.J.; Kramer A.; Chesnaye N.C.; Couchoud C.; Sánchez-Álvarez J.E.; Garneata L.; Collart F.; Hemmelder M.H.; Ambühl P.; Kerschbaum J.; Legeai C.; Del Pino Y Pino M.D.; Mircescu G.; Mazzoleni L.; Hoekstra T.; Winzeler R.; Mayer G.; Stel V.S.; Wanner C.; Zoccali C.; Massy Z.A. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 2020, 98(6):1540-1548. [CrossRef]

- Wang F.; Ao G.; Wang Y.; Liu F.; Bao M.; Gao M.; Zhou S.; Qi X. Risk factors for mortality in hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2021, 43(1):1394-1407. [CrossRef]

- Li J.; Li S.X.; Zhao L.F.; Kong D.L.; Guo Z.Y. Management recommendations for patients with chronic kidney disease during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2020, 6(2), 119-123. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira G.M.; Oliveira M.S.; Moura A.F.; Cruz C.M.S.; Moura-Neto J.A. COVID-19 in dialysis units: A comprehensive review. World J Virol. 2021,10(5):264-274. [CrossRef]

- Ng W.H.; Tipih T.; Makoah N.A.; Vermeulen J.G.; Goedhals D.; Sempa J.B.; Burt F.J.; Taylor A.; Mahalingam S. Comorbidities in SARS-CoV-2 Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. mBio. 2021, 9;12(1):e03647-20. [CrossRef]

- Ali E.T.; Sajid Jabbar A.; Al Ali H.S.; Shaheen Hamadi S.; Jabir M.S.; Albukhaty S. Extensive Study on Hematological, Immunological, Inflammatory Markers, and Biochemical Profile to Identify the Risk Factors in COVID-19 Patients. Int J Inflam. 2022, 2022:5735546. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y.D.; Ding M.; Dong X.; Zhang J.J.; Kursat Azkur A.; Azkur D.; Gan H.; Sun Y.L.; Fu W.; Li W., Liang H.L., Cao Y.Y., Yan Q., Cao C., Gao H.Y., Brüggen M.C., van de Veen W., Sokolowska M., Akdis M., Akdis C.A. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: A review. Allergy. 202.1, 76(2):428-455. [CrossRef]

- Mudatsir M.; Fajar J.K.; Wulandari L.; Soegiarto G.; Ilmawan M.; Purnamasari Y.; Mahdi B.A.; Jayanto G.D.; Suhendra S.; Setianingsih Y.A.; Hamdani R.; Suseno D.A.; Agustina K.; Naim H.Y.; Muchlas M.; Alluza H.H.D.; Rosida N.A.; Mayasari M.; Mustofa M.; Hartono A.; Aditya R.; Prastiwi F.; Meku F.X.; Sitio M.; Azmy A.; Santoso A.S.; Nugroho R.A. .; Gersom C.; Rabaan A.A.; Masyeni S.; Nainu F., Wagner A.L.; Dhama K.; Harapan H. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res. 2020, 9:1107.

- Roedl K.; Jarczak D.; Thasler L.; Bachmann M.; Schulte F.; Bein B.; Weber C.F.; Schäfer U.; Veit C.; Hauber H.P.; Kopp S.; Sydow K.; de Weerth A.; Bota M.; Schreiber R.; Detsch O.; Rogmann J.P.; Frings D.; Sensen B.; Burdelski C.; Boenisch O.; Nierhaus A.; de Heer G.; Kluge S. Mechanical ventilation and mortality among 223 critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A multicentric study in Germany. Aust Crit Care. 2021, 2:167-175. [CrossRef]

- Hou Y.C.; Lu K.C.; Kuo K.L. The Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccines in Chronic Kidney Disease and Kidney Transplantation Patients: A Narrative Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 885. [CrossRef]

- Hartzell S.; Bin S.; Benedetti C.; Haverly M.; Gallon L.; Zaza G.; Riella L.V.; Menon M.C.; Florman S.; Rahman A.H.; Leech J.M.; Heeger P.S.; Cravedi P. Evidence of potent humoral immune activity in COVID-19-infected kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020, 20(11):3149-3161. [CrossRef]

- Candon S.; Guerrot D.; Drouot L.; Lemoine M.; Lebourg L.; Hanoy M.; Boyer O.; Bertrand D. T cell and antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2: Experience from a French transplantation and hemodialysis center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Transplant. 2021, 2, 854-863. [CrossRef]

- Kato S.; Chmielewski M.; Honda H.; Pecoits-Filho R.; Matsuo S.; Yuzawa Y.; Tranaeus A.; Stenvinkel P.; Lindholm B. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008, 5,1526-33. [CrossRef]

- Allon M.; Depner T.A.; Radeva M.; Bailey J.; Beddhu S.; Butterly D.; Coyne D.W.; Gassman J.J.; Kaufman A.M.; Kaysen G.A.; Lewis J.A.; Schwab S.J.; HEMO Study Group. Impact of dialysis dose and membrane on infection-related hospitalization and death: results of the HEMO Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003, 7, 1863-70. [CrossRef]

- James M.T.; Quan H.; Tonelli M.; Manns B.J.; Faris P.; Laupland K.B.; Hemmelgarn BR.; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. CKD and risk of hospitalization and death with pneumonia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009,1,24-32. [CrossRef]

- Rista E.; Dervishi D.; Cadri V.; Akshija I.; Saliaj K.; Bino S.; Puca E.; Harxhi A. Predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: A single-center experience. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023, 17(4):454-460. [CrossRef]

- Selvaskandan H.; Hull K.L.; Adenwalla S.; Ahmed S.; Cusu M.C.; Graham-Brown M.; Gray L.; Hall M.; Hamer R.; Kanbar A.; Kanji H.; Lambie M.; Lee H.S.; Mahdi K.; Major R.; Medcalf J.F.; Natarajan S.; Oseya B.; Stringer S.; Tabinor M.; Burton J. Risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity among patients on maintenance haemodialysis: a retrospective multicentre cross-sectional study in the UK. BMJ Open. 2022, 5:e054869. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi K.;, Nangaku M.; Ryuzaki M.; Yamakawa T.; Yoshihiro O.; Hanafusa N.; Sakai K.; Kanno Y.; Ando R.; Shinoda T.; Nakamoto H.; Akizawa T.; COVID-19 Task Force Committee of the Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians, the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy, and the Japanese Society of Nephrology. Survival and predictive factors in dialysis patients with COVID-19 in Japan: a nationwide cohort study. Ren Replace Ther. 2021, 7(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Ashby D.R.; Caplin B.; Corbett R.W.; Asgari E.; Kumar N.; Sarnowski A.; Hull R.; Makanjuola D.; Cole N.; Chen J.; Nyberg S.; McCafferty K.; Zaman F.; Cairns H.; Sharpe C.; Bramham K.; Motallebzadeh R.; Anwari K.J.; Salama A.D.; Banerjee D; Pan-London COVID-19 Renal Audit Group. Severity of COVID-19 after Vaccination among Hemodialysis Patients: An Observational Cohort Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 17(6):843-850. [CrossRef]

- Turgutalp K.; Ozturk S.; Arici M.; Eren N.; Gorgulu N.; Islam M.; Uzun S.; Sakaci T.; Aydin Z.; Sengul E.; Demirelli B.; Ayar Y.; Altiparmak M.R.; Sipahi S.; Mentes I.B.; Ozler TE.; Oguz EG.; Huddam B.; Hur E.; Kazancioglu R.; Gungor O.; Tokgoz B.; Tonbul H.Z.; Yildiz A.; Sezer S.; Odabas A.R.; Ates K. Determinants of mortality in a large group of hemodialysis patients hospitalized for COVID-19. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Giot M.; Robert T.; Brunet P.; Resseguier N.; Lano G. Vaccination against COVID-19 in a haemodialysis centre: what is the risk of bleeding complications? Clin Kidney J. 2021, 14(6):1701-1703.

- Ziadi A.; Hachimi A.; Admou B.; Hazime R.; Brahim I.; Douirek F.; Zarrouki Y.; El Adib A.R, Younous S.; Samkaoui A.M. Lymphopenia in critically ill COVID-19 patients: A predictor factor of severity and mortality. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021, 43(1):e38-e40. [CrossRef]

- Niu J.; Sareli C.; Mayer D.; Visbal A.; Sareli A. Lymphopenia as a Predictor for Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Single Center Retrospective Study of 4485 Cases. J Clin Med. 2022, 11(3):700. [CrossRef]

- Hartantri Y.; Debora J.; Widyatmoko L.; Giwangkancana G.; Suryadinata H.; Susandi E.; Hutajulu E.; Hakiman A.P.A.; Pusparini Y.; Alisjahbana B. Clinical and treatment factors associated with the mortality of COVID-19 patients admitted to a referral hospital in Indonesia. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023,100167. [CrossRef]

- Zeng B.; Zhou J.; Peng D.; Dong C.; Qin Q. The prevention and treatment of COVID-19 in patients treated with hemodialysis. Eur J Med Res. 2023, 28(1):410. [CrossRef]

- Sibbel S.; McKeon K.; Luo J.; Wendt K.; Walker A.G.; Kelley T.; Lazar R.; Zywno M.L.; Connaire J.J.; Tentori F.; Young A.; Brunelli S.M. Real-World Effectiveness and Immunogenicity of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Patients on Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Espi M.; Charmetant X.; Barba T.; Mathieu C.; Pelletier C.; Koppe L.; Chalencon E.; Kalbacher E.; Mathias V.; Ovize A.; Cart-Tanneur E.; Bouz C.; Pellegrina L.; Morelon E.; Juillard L.; Fouque D.; Couchoud C.; Thaunat O.; REIN Registry. A prospective observational study for justification, safety, and efficacy of a third dose of mRNA vaccine in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2022, 390-402. [CrossRef]

- Ashby D.R.; Caplin B.; Corbett RW.; Asgari E.; Kumar N.; Sarnowski A.; Hull R.; Makanjuola D.; Cole N.; Chen J.; Nyberg S.; Forbes S.; McCafferty K.; Zaman F.; Cairns H.; Sharpe C.; Bramham K.; Motallebzadeh R.; Anwari K.; Roper T.; Salama A.D.; Banerjee D.; pan-London Covid-19 renal audit groups. Outcome and effect of vaccination in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection in hemodialysis patients: a cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022, 37(10), 1944-1950. [CrossRef]

- Bell S.; Campbell J.; Lambourg E.; Watters C.; O’Neil M.; Almond A.; Buck K.; Carr EJ.; Clark L.; Cousland Z.; Findlay M.; Joss N.; Metcalfe W.; Petrie M.; Spalding E.; Traynor J.P.; Sanu V.; Thomson P.; Methven S.; Mark P.B: The impact of vaccination on incidence and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with kidney failure in Scotland. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2022, 33: 677–686. [CrossRef]

| Overall, N=442 |

Unvaccinated, n=173 |

1 dose, n=19 |

2 doses, n=112 | 3 doses, n=138 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 285 (64.5%) | 118 (68.2) | 9 (47.7) | 68 (60.7) | 90 (65.2) | 0.240 |

| Age, years ± SD | 63 ± 13.7 | 62 ± 14.3 | 63 ± 15.9 | 64 ± 13.9 | 65 ± 12.3 | 0.162 |

| Primary kidney disease, n (%) Hypertension Diabetes Glomerulonephritis Lupus nephritis and vasculitis Polycystic kidney disease Others |

169 (38.2) 115 (26.0) 36 (8.1) 21 (4.8) 27 (6.1) 74 (16.7) |

62 (35.8) 42 (24.3) 17 (9.8) 9 (5.2) 9 (5.2) 34 (19.7) |

9 (47.4) 3 (15.8) 2 (10.5) 3 (15.8) 1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) |

43 (38.4) 33 (29.5) 5 (4.5) 4 (3.6) 7 (6.3) 20 (17.9) |

55 (39.9) 37 (26.8) 12 (8.7) 5 (3.6) 10 (7.2) 19 (13.8) |

0.502 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) Hypertension Diabetes Cardiomyopathy Cerebrovascular disease Malignancy COPD |

374 (84.6) 125 (28.3) 155 (35.1) 32 (7.2) 45 (10.2) 17 (3.8) |

144 (83.2) 47 (27.2) 64 (37.0) 14 (8.1) 15 (8.7) 7 (4.0) |

16 (84.2) 3 (15.8) 9 (47.4) 2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) 0 (0) |

94 (83.9) 35 (31.3) 32 (28.6) 9 (8.0) 12 (10.7) 5 (4.5) |

120 (87.0) 40 (29.0) 50 (36.2) 7 (5.1) 16 (11.6) 5 (3.6) |

0.831 0.554 0.295 0.668 0.857 0.822 |

| Duration of dialysis, years, median (IQR) | 4 (7) | 4.73 (8) | 3.75 (9) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | 0.920 |

| Overall, N=442 |

Unvaccinated, n=173 |

1 dose, n=19 |

2 doses, n=112 | 3 doses, n=138 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The X-ray signs of pneumonia, n (%) Withut pneumona Unilateral pneumonia Bilateral pneumonia |

189 (42.8) 26 (5.9) 227 (51.3) |

50 (28.9) 16 (9.2) 107 (61.8) |

5 (26.3) 2 (10.5) 12 (63.2) |

46 (41.1) 5 (4.5) 61 (54.5) |

88 (63.8) 3 (2.2) 47 (34.1) |

<0.001 |

| Oxigenation, n (%) Ambient air Low flow nasal cannula High Flow face mask Noninvasive ventilation Invasive mechanical ventilation |

268 (60.6) 83 (18.8) 10 (2.3) 15 (3.4) 66 (14.9) |

83 (48.0) 40 (23.1) 5 (2.9) 11 (6.4) 34 (19.7) |

10 (52.6) 7 (36.8) 0 (0) 0 (0) 2 (10.5) |

64 (57.1) 22 (19.6) 3 (2.7) 1 (0.9) 22 (19.6) |

111 (80.4) 14 (10.1) 2 (1.4) 3 (2.2) 8 (5.8) |

<0.001 |

| Antivirotic, n (%) | 59 (13.3) | 19 (11.0) | 1 (5.3) | 14 (12.5) | 25 (18.1) | 0.196 |

| Regen Cov, n (%) | 22 (5.0) | 6 (3.5) | 1 (5.3) | 6 (5.4) | 9 (6.5) | 0.667 |

| Time from the last vaccine dose to the onset of illness, day, median (IQR) | 141 (170) | - | 14 (225) | 168 (120) | 122.5 (171) | <0.001 |

| Time from illness onset to outcome, day, median (IQR) | 15 (11) min-max 1-61 | 15 (12) | 15 (18) | 17 (10) | 14 (11) | 0.137 |

| Oxygen saturation on admission, % ± SD | 96 ± 5.3 | 95 ± 6.6 | 95 ± 4.1 | 96 ± 4.9 | 96 ± 4.1 | 0.017 |

| Systolic blood pressure on admission, mm/Hg, mean ± SD | 130 ± 22.9 | 134 ± 25.4 | 130 ± 24.3 | 133 ± 17.7 | 130 ± 23.4 | 0.401 |

| Complication, n (%) Without complication Major bleeding Thrombosis Bleeding + thrombosis |

383 (86.7) 34 (7.7) 21 (4.8) 4 (0.9) |

140 (80.9) 20 (11.6) 12 (6.9) 1 (0.6) |

16 (84.2) 3 (15.8) 0 (0) 0 (0) |

98 (87.5) 6 (5.4) 5 (4.5) 3 (2.7) |

129 (93.5) 5 (3.6) 4 (2.9) 0 (0) |

0.022 |

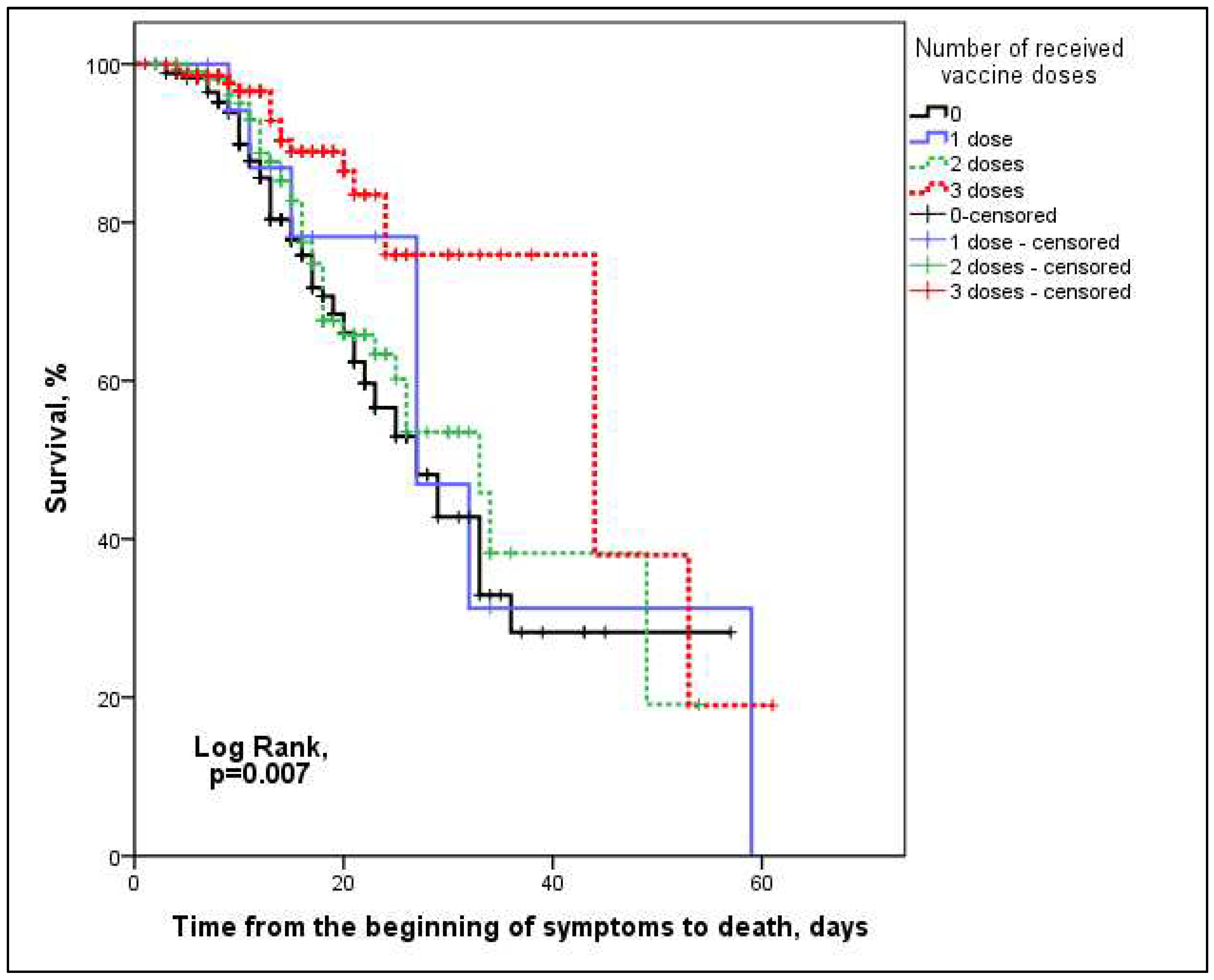

| Death, n (%) | 119 (26.9) | 60 (34.7) | 7 (36.8) | 35 (31.3) | 17 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| Overall, N=442 |

Unvaccinated, n=173 |

1 dose, n=19 |

2 doses, n=112 | 3 doses, n=138 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count*, mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 3.77 | 7.3 ± 4.39 | 5.8 ± 1.82 | 7.1 ± 3.51 | 7.0 ± 3.30 | 0.371 |

| Ly count*, median (IQR) | 0.93 (0.70) | 0.84 (0.67) | 0.95 (0.54) | 0.91 (0.73) | 1.0 (0.66) | 0.207 |

| Hgb, g/L, mean ± SD | 104 ± 17.3 | 103 ± 19.6 | 99 ± 16.4 | 106 ± 16.0 | 104 ± 15.0 | 0.213 |

| D-dimer, mg/L, median (IQR) | 1.4 (1.72) | 1.89 (2.30) | 1.64 (1.59) | 1.30 (1.77) | 1.22 (1.05) | 0.073 |

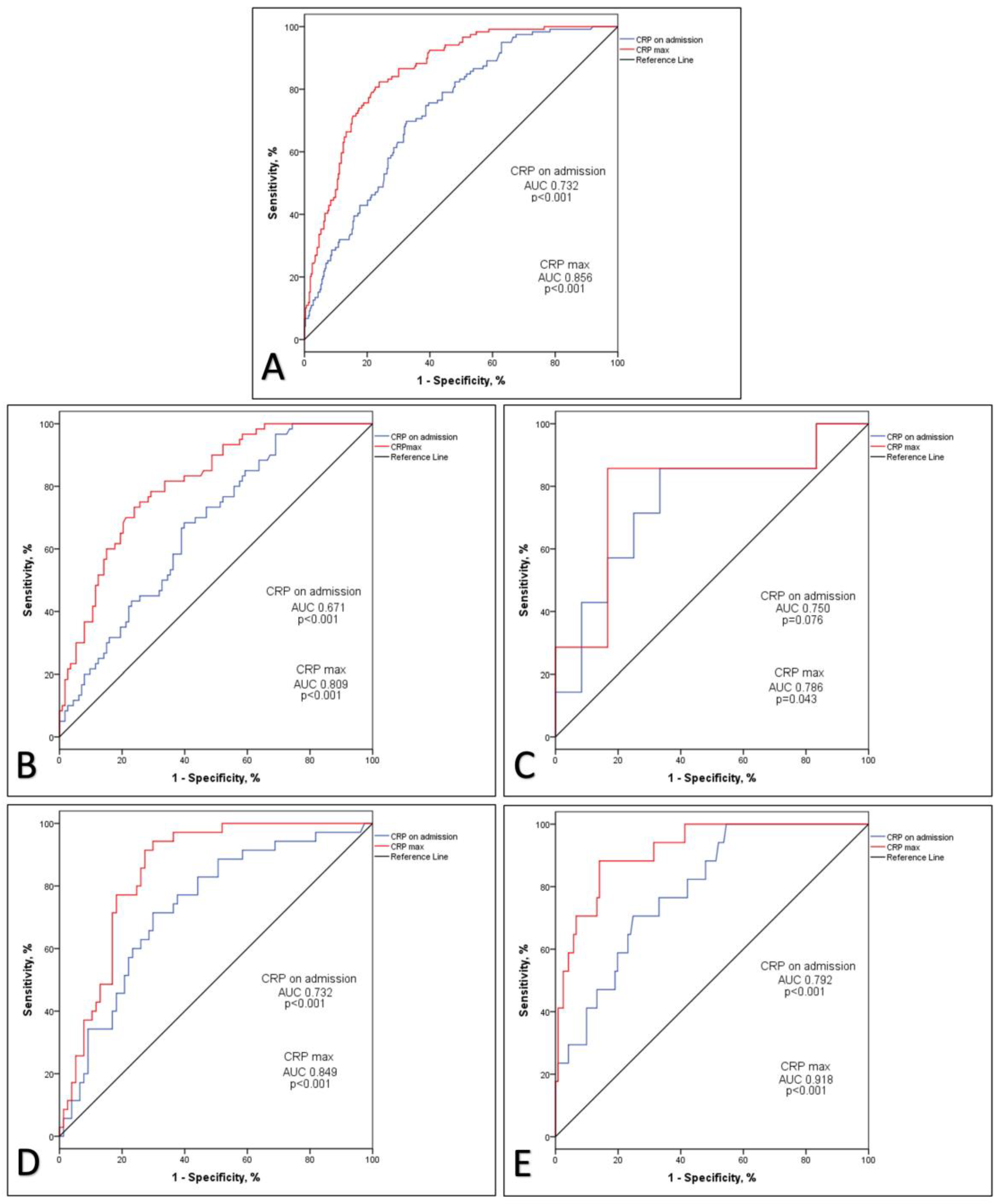

| CRP, mg/L, median (IQR) | 43.1 (82.98) | 57.1 (98.05) | 45.9 (85.5) | 45.5 (72.5) | 25.9 (63.45) | <0.001 |

| Ferritin, µg/L, median (IQR) | 923.3 (1806.48) | 1108.0 (1801.80) | 1557.3 (1748.3) | 753.0 (1678.1) | 624.8 (1287.0) | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L, mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 1.61 | 5.1 ± 1.76 | 5.5 ± 1.52 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 1.48 | 0.127 |

| Albumin, g/L, mean ± SD | 36 ± 5.8 | 34 ± 6.0* | 36 ± 6.7 | 36 ± 6.0 | 37 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Overall, N=442 |

Unvaccinated, n=173 |

1 dose, n=19 |

2 doses, n=112 | 3 doses, n=138 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC max* count, mean ± SD | 12.4 ± 8.05 | 13.5±7.95 | 12.8±6.36 | 13.4±9.06 | 10.2±7.06 | 0.001 |

| Ly min** counts, median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.69) | 0.49 (0.65) | 0.47 (0.59) | 0.56 (0.67) | 0.80 (0.62) | <0.001 |

| Ly max counts, median (IQR) | 1.25 (4.47) | 1.27 (1.05) | 1.18 (0.71) | 1.20 (0.83) | 1.25 (0.80) | 0.701 |

| D-dimer max, mg/L, median (IQR) | 2.16 (3.88) | 2.9 (4.81) | 2.19 (1.98) | 2.20 (3.80) | 1.42 (2.54) | 0.002 |

| CRP max, mg/L, median (IQR) | 78.6 (153.3) | 109.3 (149.30) | 100.3 (153.3) | 77.85 (181.88) | 37.8 (94.78) | <0.001 |

| Ferritin max, µg/L, median (IQR) | 1277.8 (3322.1) | 1976.2 (3853.70) | 2309.8 (3011.8) | 1104.4 (3448.8) | 766.3 (1893.4) | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen max, g/L, mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 1.82 | 5.7 ± 1.89 | 6.4 ± 1.69 | 5.8 ± 1.78 | 5.1 ± 1.69 | 0.001 |

| IL6 max, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 49.1 (164.25) | 49.1 (231.25) | 51.75 (71.82) | 64.9 (186.84) | 36.2 (190.61) | 0.808 |

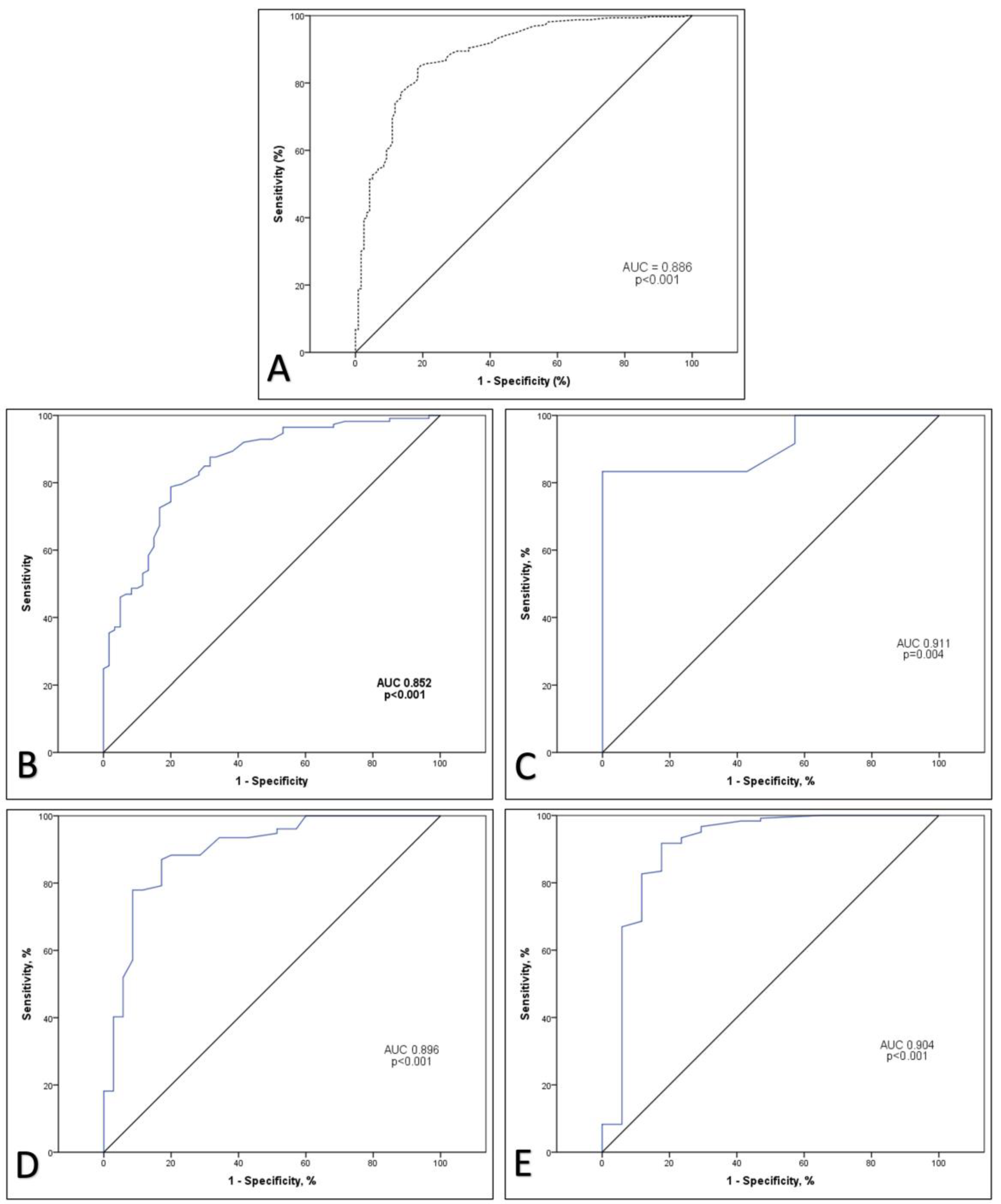

| B | p | HR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.025 | 0.001 | 1.025 | 1.010-1.040 |

| Male | -0.047 | 0.808 | 0.954 | 0.653-1.394 |

| Hypertension | 0.303 | 0.288 | 1.354 | 0.774-2.371 |

| Diabetes | 0.202 | 0.300 | 1.224 | 0.835-1.794 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 0.876 | <0.001 | 2.400 | 1.666-3.458 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.471 | 0.115 | 1.604 | 0.892-2.874 |

| Malignancy | -0.044 | 0.877 | 0.957 | 0.546-1.676 |

| COPD | 0.021 | 0.968 | 1.021 | 0.375-2.776 |

| The X-ray signs of pneumonia, n (%) Withut pneumona Unilateral pneumonia Bilateral pneumonia |

- 0.913 0.586 |

- 0.191 <0.001 |

- 3.299 19.888 |

- 0.551-19.761 6.312-62.664 |

| Vaccination: Unvaccinated 1 dose 2 doses 3 doses |

- -0.216 -0.180 -0.923 |

- 0.603 0.399 0.001 |

- 0.806 0.836 0.397 |

- 0.357-1.817 0.550-1.268 0.231-0.683 |

| Antivirotic | -0.365 | 0.253 | 0.694 | 0.372-1.298 |

| RegenCov | -0.805 | 0.176 | 0.447 | 0.139-1.435 |

| Duration of dialysis | 0.015 | 0.323 | 1.015 | 0.968-1.044 |

| Complication Without complication Hemorrhage Thrombosis Hemorrhage + thrombosis |

- 0.876 0.515 0.392 |

- <0.001 0.108 0.508 |

- 2.401 1.674 1.480 |

- 1.539-3.745 0.893-3.140 0.463-4.729 |

| WBC od admission | 0.075 | <0.001 | 1.077 | 1.038-1.118 |

| Ly on admission | -0.856 | <0.001 | 0.425 | 0.274-0.660 |

| CRP on admission | 0.006 | <0.001 | 1.006 | 1.004-1.007 |

| IL-6 on admission | 0.001 | 0.024 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.002 |

| Ferritin on admission | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 1.001-1.002 |

| Fibrinogen on admission | 0.063 | 0.279 | 1.065 | 0.950-1.193 |

| D dimer on admission | 0.053 | <0.001 | 1.054 | 10.33-1.076 |

| Le max | 0.053 | <0.001 | 1.055 | 1.038-1.071 |

| Ly min | -2.781 | <0.001 | 0.062 | 0.027-0.143 |

| Ly max | -0.371 | 0.024 | 0.690 | 0.500-0.952 |

| D-dimer max | 0.022 | <0.001 | 1.022 | 1.012-1.033 |

| CRP max | 0.007 | <0.001 | 1.007 | 1.005-1.009 |

| Ferritin max | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 1.001-1.002 |

| IL6 max | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 1.001-1.002 |

| B | p | HR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyopathy | 1.213 | <0.001 | 3.364 | 1.874-6.040 |

| CRP on admission | 0.004 | 0.005 | 1.004 | 1.001-1.008 |

| CRP max | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.006 | 1.002-1.010 |

| IL6 max | 0.001 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 1.001-1.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).