1. Introduction

Several training methods are effective in increasing muscular power and improving athletic performance. Post-activation potentiation enhancement (PAPE) has been suggested as a means to acutely enhance short-duration athletic performance that relies on maximal power production. It refers to the acute improvement in muscular function based on its contractile history, strongly influenced by factors including muscle temperature changes, intramuscular fluid accumulation and muscle activation [

1,

2]. The conditioning stimulus to induce PAPE can be achieved through different methods and modes of activities, including isometric exercises, medium or heavy resistance conditioning, and plyometrics, leading to a higher rate of force development or greater jumping height [

3,

4], and sprint performance [

5,

6]. Male elite rugby players experienced a 5% increase in jumping height [

7], and male adolescent soccer players showed a significant improvement in repeated sprint performance after performing loaded back squats [

8]. Even in young female soccer players, combined balance and strength training acted as an effective PAPE stimulus to enhance jumping performance [

9]. These findings highlight the potential impact of PAPE on sports activities with high power demands.

Isometric exercises have been effective in triggering PAPE responses, especially in individuals with high-strength capabilities [

1]. A previous study suggested that 15 short, intermittent, and repetitive maximal voluntary contractions (MVC) provide the most effective isometric stimulus to induce PAPE [

10]. A 3x3 s stimulus of isometric half-squat led to increased jumping performance due to a greater rate of force development in trained individuals [

1]. Additionally, plyometric exercises effectively produce acute improvements in countermovement jump and sprint performance [

11]. They may even offer similar benefits compared to high-loaded resistance exercises when used as conditioning activities by recreational athletes before running [

12]. Determining the best interaction between conditioning stimulus and rest period is a determined factor in PAPE responses [

13]. This interaction depends on several factors, such as the type, the intensity of stimulus, and the training background of the participants.

The high-loaded resistance stimulus typically involves multi-joint free-weight exercises with loads exceeding 85%, which has gained widespread popularity as a potential effective stimulus, to enhance strength and power performance due to PAPE. Such loading of the muscle-tendon system is known to enhance subsequent higher-velocity exercises like sprints or vertical jumps [

14,

15]. A previous study has shown that back squats enhanced jumping height and power production during countermovement jumps, particularly among international sprint swimmers [

16]. Similarly, in rugby players, PAPE was observed after squats at nearly twice their body weight [

7]. Additionally, significant increases in countermovement jump height were reported, attributed to greater muscular activity in the gluteus during parallel squats [

17]. On the contrary, a recent study found that eccentric and concentric squats did not impact final countermovement jump performance in track and field athletes [

18]. Despite the efficacy of high-loaded exercises in inducing the PAPE effect, their practical applicability remains uncertain. The data on the effects of strength exercises on subsequent jump performance, particularly the interaction between the type of stimulus and optimal rest periods to maximize power, are limited and warrant further investigation.

Trained athletes specializing in jumping events and sprinting often include plyometrics and heavy resistance training in their workout routines. These athletes usually show neural activation, architectural features, and a higher proportion of fast muscle fibers, all influencing their power production during athletic events. Chronic resistance training increases their resistance to fatigue through improved buffering capacity [

19,

20] and increased protection against skeletal muscle damage [

21]. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that conditioned athletes experience less fatigue than non-athletes, leading to the likelihood of the PAPE effect occurring closer to the conditioning stimulus. On the other hand, athletes with predominantly fast-twitch fibers might be negatively impacted by short rest periods between the conditioning stimulus and their athletic performance due to the limited fatigability of these fibers. From a practical standpoint, rest periods of 2 to 5min highly align with the common rest period provided to finalists during jumping events.

The research hypothesis of the present study was that eccentric conditioning activity could lead to an increase in the performance of jumping ability after a short rest period. Hence, the primary aim of this research was to assess the impact of PAPE induced by the half-squat exercise on the vertical jumping performance (including jump height, peak power, and work) in male jumpers, utilizing a brief rest interval.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A power analysis using G*Power software guided our study's sample size determination. The analysis was based on a repeated measures ANOVA design, with effect Size: 0.35, number of conditions: 2 (intervention and control), number of measures: 3 (PRE, POST1, and POST2), correlation Among Repeated Measures: 0.6 (Estimated by ICC). The power analysis recommended a sample size of 20 participants to achieve 97% statistical power. Twenty male athletes (age: 21.2 ± 1.7 years, height: 191.1 ± 3.3 cm, body mass: 81.56 ± 7.3 kg) with a minimum of 12 training hours per week, signed informed consent before their inclusion in the study. All the participants were athletes of jumping events in track and field (12 long jumpers and 8 high jumpers). Approval for the experiment was obtained from University Ethics Committee on Human Research (ERC-008/2020). None of the participants were involved in any particular strength and/or plyometric training program four days before the experimental sessions.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

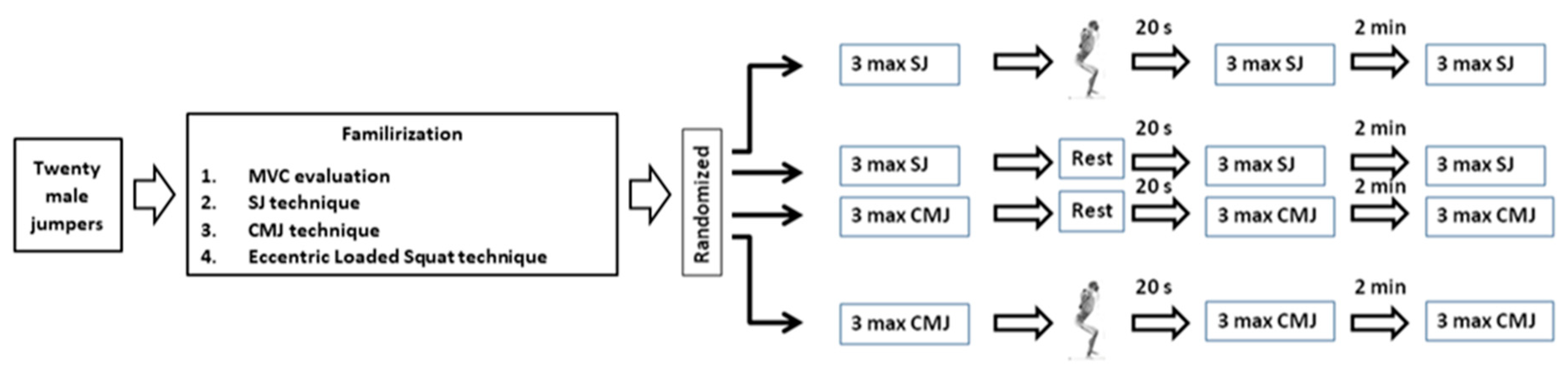

Participants visited the laboratory on five separate days (

Figure 1). During the first visit, the participants familiarized themselves with the testing setup (Squat Jump (SJ), Countermovement Jump (CMJ), the stimulus procedure with eccentric half-squat exercise and measured the maximal load for one repetition (1 RM, MVC), starting from six repetitions and reaching to one. All jumps were performed on a three-dimension platform (Kistler Type 9281C, Kistler Instruments, Winterthur, Switzerland) with ground reaction forces (GRF) to be recorded. The four other visits were experimental sessions. Two sessions served as control (no conditioning activity = rest) and the two others served as intervention (PAPE = eccentric half-squat) sessions. Moreover, SJs were evaluated during two sessions (one control and one PAPE) and CMJs were evaluated during the two others. All sessions were randomly presented. All test days started with a 6min warm-up routine on a static bicycle. Following the warm-up, the baseline of the jumping test (depending on the day) was performed (PRE) and repeated after the conditioning stimulus (POST1). Then, volunteers rested for 2min (POST2), and they repeated the jumps. The best of three jumps, based on maximum height output, was used for further analysis. The maximum power, maximum work of eccentric and concentric phases, and lower limb stiffness were analyzed and evaluated.

2.3. Conditioning Activity Procedure

The conditioning stimulus included 5 repetitions of eccentric half-squat at 85% of MVC, with the knee joint angle reaching lower than 90° with each repetition lasting 4’’ (almost 30°/s) and regulated by a metronome. The bar was placed on the stops of squat rack at the end of the eccentric phase while the assistants lifted the Olympic bar to the initial position. During jump tests, the participants performed three SJs or CMJs with 15s intervals between the jumps (

Figure 1). The total SJs or CMJs test duration, including the rest intervals and duration of the jumps, did not exceed 90s each time. In the control session, the same procedure was followed, and the performance of the jumps was evaluated at the same time points, except that the participants rested passively (seated), during the conditioning activity. All the sessions were conducted at approximately the same time of day for all participants, and there was no control for diet or hydration (

Figure 1).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM Corp., Version 25.0, Armonk, New York, USA). The statistical approach included separate analyses for SJ and CMJ. For each jump type, a repeated measures ANOVA (2x3) was conducted. This analysis incorporated the ICC-calculated correlation among repeated measures, accommodating within-subject effects and potential interactions between time points and conditions. To assess the practical significance of the observed differences, effect sizes were calculated. Additionally, post hoc analyses were conducted to explore the nature of the significant interaction between conditions and time points. Notable differences between PRE, POST1, and POST2 jumps were found for key parameters, including maximum power, work, maximum jump height, and lower limb stiffness. This comprehensive approach to data analysis adds depth to the interpretation of the results, helping to understand whether there are significant differences and the nature and magnitude of these differences. A significance level of p<.05 was chosen to assess statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Squat Jump

The ANOVA analysis showed no statistically significant differences in the maximum SJ height with respect to time and the three measurements [F(1,18)= 1.3, p= 0.458], and interaction between conditions and time [F(1,18)= 3.2, p= 0.062]. In addition, there was no statistically significant difference in produced SJ positive work in time [F(2,18)= 0.3, p= 0.853] and interaction [F(2,18)=1.4, p= 0.343]. Finally, there were no statistically significant difference in the maximum power between the PRE, POST1 and POST2 jumps in either of the two conditions [F(2,18) = 0.6, p=.526] and interaction between conditions and time [F(2,18) = 0.6, p= 0.316].

3.2. Counter Movement Jump

The ANOVA analysis showed no statistically significant differences in the maximum CMJ height with respect to time and the three measurements [F(1,18)= 1.1, p= 0.368], and interaction between groups and time [F(1,18)= 3.7, p= 0.053;

Table 1]. The work during the eccentric phase, revealed significant main effect of time [F(2,18)= 9.9, p= 0.002]. However, there was no interaction between group and time [F(2,18)= 0.7, p= 0.505;

Table 1]. In contrast, there was no statistically significant difference in produced concentric work in time [F(2,18)= 0.4, p= 0.708] and interaction [F(2,18)=2.6, p= 0.101;

Table 1]. Power was not statistically different during eccentric and concentric phases across time (

Table 1) and all three measures [F(2,18) = 1.6, p=.236; F(2,18) = 1.9, p= 0.177, respectively] and interaction between group and time [F(2,18) = 1.6, p= 0.237; F(2,18) = 1.8, p= 0.195, respectively]. Finally, the lower limb stiffness during the eccentric phase did not show any statistical differences with time [F(2,18) = 1.2, p= 0.336] or condition x time interaction [F(2,18) = 1.1, p= 0.358;

Table 1].

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate whether the eccentric back-squat followed by a 20s and a 2min rest periods, as a preliminary conditioning stimulus, could improve vertical jumping performance. The findings of the present study indicated that the 2min rest period after five eccentric half-squats at 85% did not improve SJ and CMJ performance variables.

Multi-joint exercises, such as squats and half-squat, are considered effective conditioning stimuli to induce PAPE, leading to improved performance [

2,

15]. In the present study, a half-squat leading the knee joint lower than 90° was used, since it enables to cause greater activation of the lower limb muscle groups [

17]. However, our findings demonstrated that the jump tests were not improved after the conditioning stimulus. A previous study has shown that the optimal rest period between the conditioning stimulus and the test varies among individuals and seems to depend on factors such as age, sex, and training background [

20]. In the present study, all the participants were male jumper athletes, with eleven of them being long jumpers and the rest of them being high jumpers. Moreover, the participants’ age did not vary with a very small standard deviation. Therefore age, sex and training background could not be considered responsible for the observed findings.

This sample and the experimental procedure of the present study, enable us to record the effect of the conditioning stimulus on this specific population. Given the above, it is safe to conclude the effects of the above protocol on jumping performance were recorded. Previous studies focused on rest periods have demonstrated conflicting results. A rest period of 7 to 10min should be considered the optimal length to enhance power production after a conditioning stimulus, despite the evidence showing a range from short to long rest period that PAPE could be induced [

20]. However, in the present study, a shorter rest period was used, which mimics the procedure during jumping events at the track and field. Our results showed that the 20s and 2min rest periods is quite short to lead to PAPE. While systematic strength training for jumping events may lead to resistance against muscle fatigue [

19,

20], the present findings suggest that the 2-minute rest period following eccentric half-squat is not sufficient to induce PAPE. Since subsequent power production and performance depend on the balance between potentiation and fatigue, one explanation for the lack of improvement could be the higher level of fatigue compared to the potentiating effect of the conditioning activity. Previous report [

22] demonstrated that subjects with a higher percentage of fast twitch muscle fibers induced a greater PAPE compared to predominantly slow twitch subjects. However, they also experienced higher fatigue during maximal voluntary contractions [

22]. These findings suggest that subjects with a high proportion of fast twitch fibers may have greater PAPE, but may be more prone to experience higher fatigue during conditioning when the rest period is short (2min).

Regarding the lower limbs and jumping ability, it was demonstrated that eccentric half-squat could induce the PAPE effect but not after the stimulus [

18]. According to the previous study, eccentric half-squat increased jumping height after the third minute of the rest, with most participants maximizing their performance in the sixth minute [

18]. Thus, it is likely that the lack of a positive effect of the eccentric half squat might be due to a short rest period. One possible explanation for the inefficiency of the short rest period is the longer “time under tension” of the knee extensors. It has been previously proposed that the participants tend to decrease their velocity during squats, increasing the time under tension in the muscle leading to low-frequency fatigue [

18,

23]. The short rest period likely did not allow the enhancing mechanism to outweigh the inhibitory one, leading to fatigue dominance in this stage.

Regarding the two jumping tasks, our results showed no significant effects after the conditioning stimulus. Our results are in agreement with the previous report which demonstrated that both eccentric and concentric squats do not affect jumping performance after short rest period [

18]. Despite the fact that previous studies [

16,

24] have shown the efficiency of the high-load stimulus to induce PAPE during the subsequent vertical jump, it seems that our eccentric half-squat stimulus failed to cause any improvements. The specificity of the conditioning stimulus is a determined factor about these contradicting results [

16]. Despite the effects of eccentric muscle actions on neural and muscle-tendon systems, it could not improve jumping height when used as a preconditioning stimulus. During SJ, the muscle groups are isometrically activated before the propulsion phase. The differences in muscle activation between the isometric contraction and eccentric action, during the jumping test and the conditioning stimulus, respectively, could result in no alteration of the jumping performance. Moreover, the biomechanical differences between the conditioning activity and the jumping test did not affect SJ jumping height. The participants remain at the 90° knee joint during the start of the SJ. Conversely, the knee flexion was a little greater during the conditioning activity. The depth of the squat was previously found to cause higher glutei muscles while the knee extensor activity remained the same [

17]. Thus, the predefined knee flexion during the SJ testing procedure was a limiting factor according to the principle of specificity and the possible greater glutei activation. Since the range of motion was the same before and after the stimulus, it seems that conditioning activity failed to improve force production. Our data support this notion, as both work and power during the propulsion phase of SJ were stable after the conditioning. The force production during this phase was the same, with the same range of motion leading to the same level of produced work and power after the conditioning activity. Furthermore, the controlled stretching velocity during the eccentric half-squat might, compared with the velocity of eccentric phase during CMJ, could also negatively affect jumping performance. As previously reported, dynamic contractions display PAPE effect that are joint and velocity specific [

20]. The stretching velocity during eccentric half-squats is lower than that which occurs during the eccentric phase of CMJ. Thus, the velocity difference might be account responsible for the unobserved effects. Further research is needed to establish the relationship between the stretching velocity and the PAPE effects.

While the study presents valuable insights into the acute effects of eccentric half-squats on jump performance within a specific population of male athletes specialized in jumping events, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The study's small sample size and exclusive focus on male athletes specializing in jumping events constitute important considerations regarding the generalization of the findings. Furthermore, the decision to exclude athletes from different events based on their distinct training characteristics and potential adaptations is valid. However, it's worth noting that this choice could impact the applicability of the results to a broader athletic context. Another noteworthy limitation involves the variability in strength training backgrounds among participants. Despite the similarities in strength training between the long and high jumpers, individual variations in training adaptation are plausible. Additionally, the absence of gender-based differences in PAPE responses and the lack of female participants raise inquiries about the results' transferability beyond the specific cohort examined. Addressing these limitations in future research endeavors could enrich our understanding of the factors influencing PAPE and its implications for enhancing athletic performance.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this study indicated that the specific conditioning stimulus of eccentric half-squats, followed by a 2min rest period, did not lead to significant improvements in force capability, the produced work of power, and the overall jumping performance in both SJ and CMJ tests. The results suggest that a single set of eccentric squats with a short rest period may not be effective for enhancing jumping performance in athlete populations like male jumpers. While PAPE remains a valuable concept in sports science, these results highlight the complexity of its application, influenced by factors such as conditioning stimulus specificity, rest period duration, and individual characteristics. Thus, further research is needed to record the possible effects of the PAPE stimulus on the jumping performance and the optimal interaction between the conditioning activity, the rest period, and the athletic population’s characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A. and F.A.; methodology, F.A.; software, G.C.; validation, T.K, E.A and G.C.; formal analysis, E.A and G.C.; investigation, F.A.; resources, E.A; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K, C.P. and N.B.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, F.A.; project administration, F.A.; funding acquisition, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Serres, Agios Ioannis, Greece (ERC-008/2020 and 23-08-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the subjects for the time and energy they invested in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arabatzi, F.; Patikas, D.; Zafeiridis, A.; Giavroudis, K.; Kannas, T.; Gourgoulis, V.; Kotzamanidis, C.M. The Post-Activation Potentiation Effect on Squat Jump Performance: Age and Sex Effect. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazevich, A.J.; Babault, N. Post-Activation Potentiation Versus Post-Activation Performance Enhancement in Humans: Historical Perspective, Underlying Mechanisms, and Current Issues. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esformes, J.I.; Cameron, N.; Bampouras, T.M. Postactivation Potentiation Following Different Modes of Exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 1911–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.R.; Brown, L.E.; Coburn, J.W.; Zinder, S.M. Acute Effects of Heavy-Load Squats on Consecutive Squat Jump Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzopoulos, D.E.; Michailidis, C.J.; Giannakos, A.K.; Alexiou, K.C.; Patikas, D.A.; Antonopoulos, C.B.; Kotzamanidis, C.M. Postactivation Potentiation Effects after Heavy Resistance Exercise on Running Speed. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 1278–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumeau, V.; Grospretre, S.; Babault, N. Post-Activation Performance Enhancement and Motor Imagery Are Efficient to Emphasize the Effects of a Standardized Warm-Up on Sprint-Running Performances. Sports 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilduff, L.P.; Owen, N.; Bevan, H.; Bennett, M.; Kingsley, M.I.C.; Cunningham, D. Influence of Recovery Time on Post-Activation Potentiation in Professional Rugby Players. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titton, A.; Franchini, E. Postactivation Potentiation in Elite Young Soccer Players. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2017, 13, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieske, O.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Granacher, U. Postactivation Potentiation of the Plantar Flexors Does Not Directly Translate to Jump Performance in Female Elite Young Soccer Players. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurvydas, A.; Jurgelaitiene, G.; Kamandulis, S.; Mickeviciene, D.; Brazaitis, M.; Valanciene, D.; Karanauskiene, D.; Mickevicius, M.; Mamkus, G. What Are the Best Isometric Exercises of Muscle Potentiation? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Raza, S.; Moiz, J.A.; Verma, S.; Naqvi, I.H.; Anwer, S.; Alghadir, A.H. Postactivation Potentiation Following Acute Bouts of Plyometric versus Heavy-Resistance Exercise in Collegiate Soccer Players. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.G.; Yu, L.; Duncan, B.; Renfree, A. A Plyometric Warm-Up Protocol Improves Running Economy in Recreational Endurance Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, L.B.; Haff, G.G. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2016, 46, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, S.J.; Turner, A.N.; Fletcher, I.M. Ballistic Exercise as a Pre-Activation Stimulus: A Review of the Literature and Practical Applications. Sport. Med. 2014, 44, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simitzi, V.; Tsoukos, A.; Kostikiadis, I.N.; Parotsidis, C.A.; Paizis, C.; Nassis, G.P.; Methenitis, S.K. The Acute Effects of Different High-Intensity Conditioning Activities on Sprint Performance Differ Between Sprinters of Different Strength and Power Characteristics. Kinesiology 2021, 53, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewther, B.T.; Kilduff, L.P.; Cook, C.J.; Middleton, M.K.; Bunce, P.J.; Yang, G.-Z. The Acute Potentiating Effects of Back Squats on Athlete Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 3319–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esformes, J.I.; Bampouras, T.M. Effect of Back Squat Depth on Lower-Body Postactivation Potentiation. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2997–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanis, G.C.; Tsoukos, A.; Veligekas, P.; Tsolakis, C.; Terzis, G. Effects of Muscle Action Type with Equal Impulse of Conditioning Activity on Postactivation Potentiation. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2521–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, I.P.; Harris, R.C.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, C.K.; Dang, V.H.; Lam, T.Q.; Bui, T.T.; Smith, M.; Wise, J.A. The Effects of 10 Weeks of Resistance Training Combined with β-Alanine Supplementation on Whole Body Strength, Force Production, Muscular Endurance and Body Composition. Amino Acids 2008, 34, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Duncan, N.M.; Marin, P.J.; Brown, L.E.; Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, S.M.C.; Jo, E.; Lowery, R.P.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Meta-Analysis of Postactivation Potentiation and Power: Effects of Conditioning Activity, Volume, Gender, Rst Periods, and Training Status. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, C.; Eston, R.G.; Kraemer, W.J. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage and the Repeated Bout Effect: Evidence for Cross Transfer. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, T.; Sale, D.G.; MacDougall, J.D.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Postactivation Potentiation, Fiber Type, and Twitch Contraction Time in Human Knee Extensor Muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 2131–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsolakis, C.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Nikolaou, A.; Zacharogiannis, E. Influence of Type of Muscle Contraction and Gender on Postactivation Potenetiation of Upper and Lower Limb Explosive Performance in Elite Fencers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2011, 10, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.J.; Sale, D.G. Enhancement of Jump Performance after a 5-RM Squat Is Associated with Postactivation Potentiation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).