1. Introduction

While bowel preparations used for colonoscopy are generally safe, they do not come without some side effects. The impact of bowel preparation on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is well established in the way it affects the lower GI mucosa. Many existing research discussed bowel preparation’s adverse events on the lower GI tract such as aphthoid lesions, erosions, and ulcers in the colon and rectum (1-8). On the other hand, there remains a noticeable gap in understanding how bowel prep affects the upper GI tract, with a paucity of data available on this subject. Two studies described gastric lesions following sodium phosphate prep (NaP) which is no longer commonly used in the United States due to renal toxicity (2-3). One notable observational prospective study conducted in France by Hagège et al. described the prevalence of gastric lesions in patients who underwent EGD at the time of colonoscopy following NaP prep. Among the 360 patients who underwent both procedures after NaP prep, 201 of them (consisting of 55.8%) had gastric lesions, primarily in the antral region, indicating possible irritating effect on the upper GI mucosa (9). A safety committee reviewed those lesions and determined that the prep was responsible for the lesions in about 10.3% of those patients. Another study performed in Korea by Nam et al. showed an association between NaP bowel prep and hemorrhagic gastropathy, highlighting an increased risk (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.34 - 2.74) associated with this particular preparation (10). Similar studies have not been conducted on other bowel preps such as oral sulfate solution (OSS) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) based preparations.

Gastric and duodenal lesions have recently been recognized by us during EGD performed at the same time as colonoscopy after various bowel preparations. Although these lesions did not result in major complications or require therapeutic interventions, recognizing these lesions as a consequence of the bowel preparation is pivotal to avoid misinterpretation and misdiagnosis of these lesions. The significance of identifying these confounding lesions has been acknowledged in the lower GI mucosa with suggestion to avoid using Sodium phosphate based bowel preparations in patients with suspicion of Crohn’s or IBD to avoid misinterpreting the findings (4). Yet, this has not been recognized in the upper GI mucosa so far in existing literature.

This study aims to bridge this gap by examining the association between different bowel preparation and the occurrence of gastric and duodenal lesions. Moreover, we aimed to estimate the frequency of these lesions relative to the preparation used, to offer some insights into the safety profile of different bowel preps in relation to the upper GI tract.

2. Methods

For this retrospective cohort study, we reviewed medical records of patients who underwent capsule endoscopic evaluation over 20 years, between April 2002 and November 2021. This single-center study was conducted at the University of South Alabama Division of Gastroenterology, in Mobile, Alabama. We retrieved the medical records from the PillCam SB3 software from the University of South Alabama database. IRB approval was exempted for this study as the analysis involved de-identified data. Patients’ identities and personal information were fully protected.

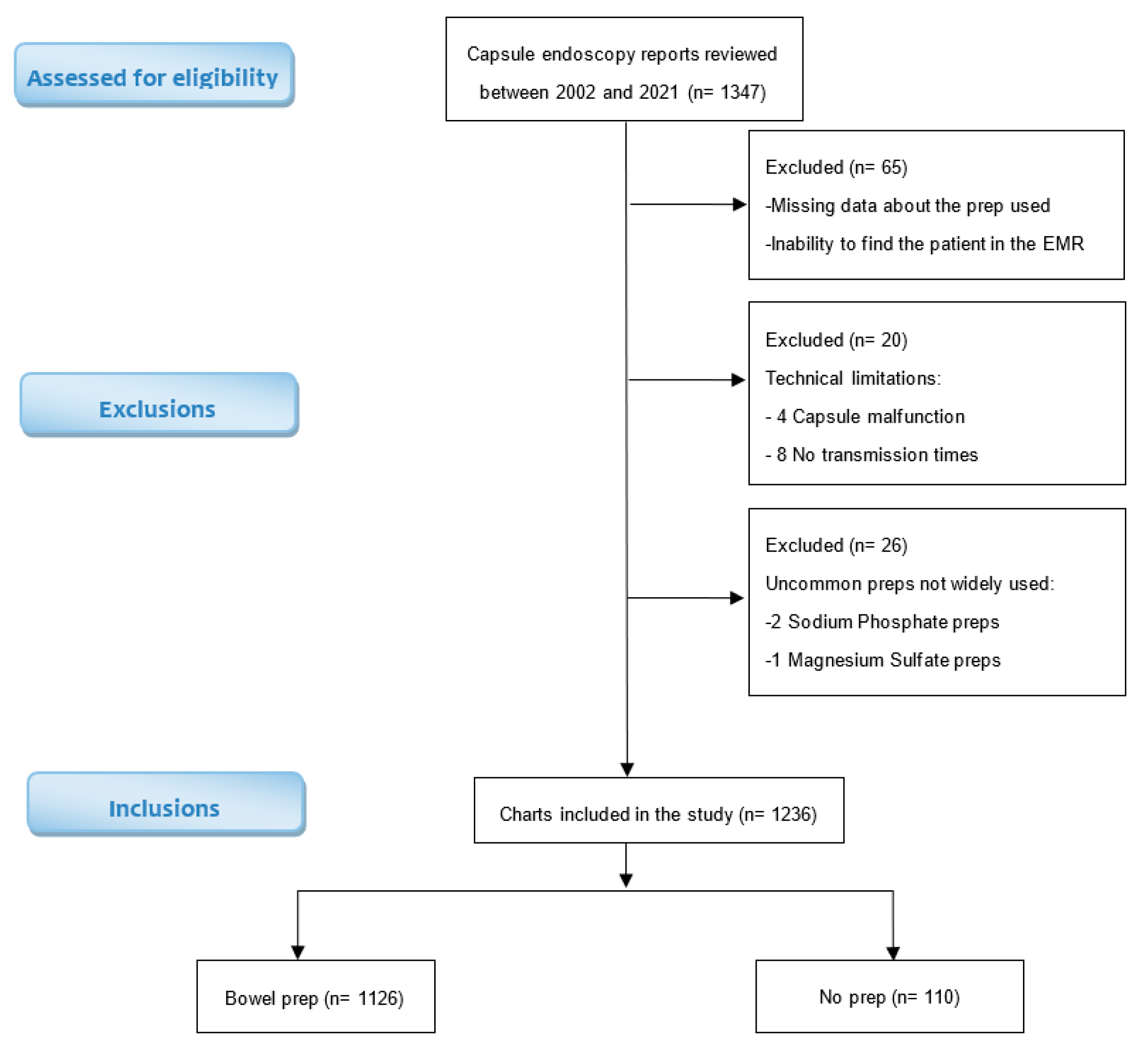

There were 1347 medical records identified on PillCam SB3 software and reviewed for patient demographics, indication of the procedure, type of preparation prescribed, timing of preparation administration relative to the procedure, and gastroduodenal findings. A total of 111 records were excluded from the study due to missing data regarding the preparation used, incomplete prep protocols, technical malfunctions, or the utilization of uncommon preparations that are not within the scope of this study [

Figure 1]. Consequently, the final study group consisted of 1236 adult subjects.

Preparations studied included polyethylene glycol lavage (PEG), PEG plus bisacodyl (PEG + bis), bisacodyl (bis), and oral sulfate solution (OSS). Preparations were prescribed according to manufacturer’s instructions. OSS was prescribed as split dose, administered both on the evening before and on the day of the procedure. PEG was prescribed as 4L dosage administered on the evening preceding the procedure. The Bisacodyl regimen was prescribed as 20mg dosage administered on the evening before the procedure. The PEG + bis combination was prescribed as bisacodyl 20mg administered at noon and 2L of PEG administered on the evening before the procedure. Patients were asked to not take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for seven days before undergoing capsule endoscopy. Most subjects were given pre-procedure metoclopramide 10 mg and simethicone 80 mg.

Gastroduodenal lesions were defined as erythematous lesions, ulcers, erosions, or inflammation, found in the stomach or duodenum. Other lesions that are unlikely to be related to the prep such as masses, polyps, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), angiodysplasias, angioectasia, and lymphangiectasia, were not counted as gastroduodenal lesions. The presence or absence of gastroduodenal lesions, as recorded on the capsule endoscopy procedure reports, was documented as a binary outcome (Yes / No).

Statistical analysis: To analyze the data, categorical variables were reported in frequencies and percentages and compared using the Pearson Chi-Square test (χ2). Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations or as medians and interquartile ranges and compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The statistical analysis was performed using the JMP statistical package. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Among the 1236 patient records included in the study, there were 498 (40.3 %) men and 738 (59.7 %) women. The mean age of the study population was 57 years, with a standard deviation of 17.8 years (

Table 1). The mean age was similar across all subgroups (ANOVA P=0.8). Gender differed between the prep group and the no prep group with male predominance (58 %) in the no prep group and female predominance (61 %) in the prep subgroups (

Table 2).

The study population consisted of 1236 patients, 1126 of them (91 %) received a bowel preparation prior to the capsule endoscopy, while 110 patients (9 %) did not receive any prep prior to the procedure. Among the 1126 patients who received bowel prep prior to the capsule endoscopy, 773 (68.6 %) received oral sulphate solution (OSS), 178 (15.8 %) received Polyethylene glycol (PEG), 137 (12.2 %) received Bisacodyl only (Bis), and 38 (3.4 %) received Polyethylene glycol and Bisacodyl (PEG + BIS). (

Table 3)

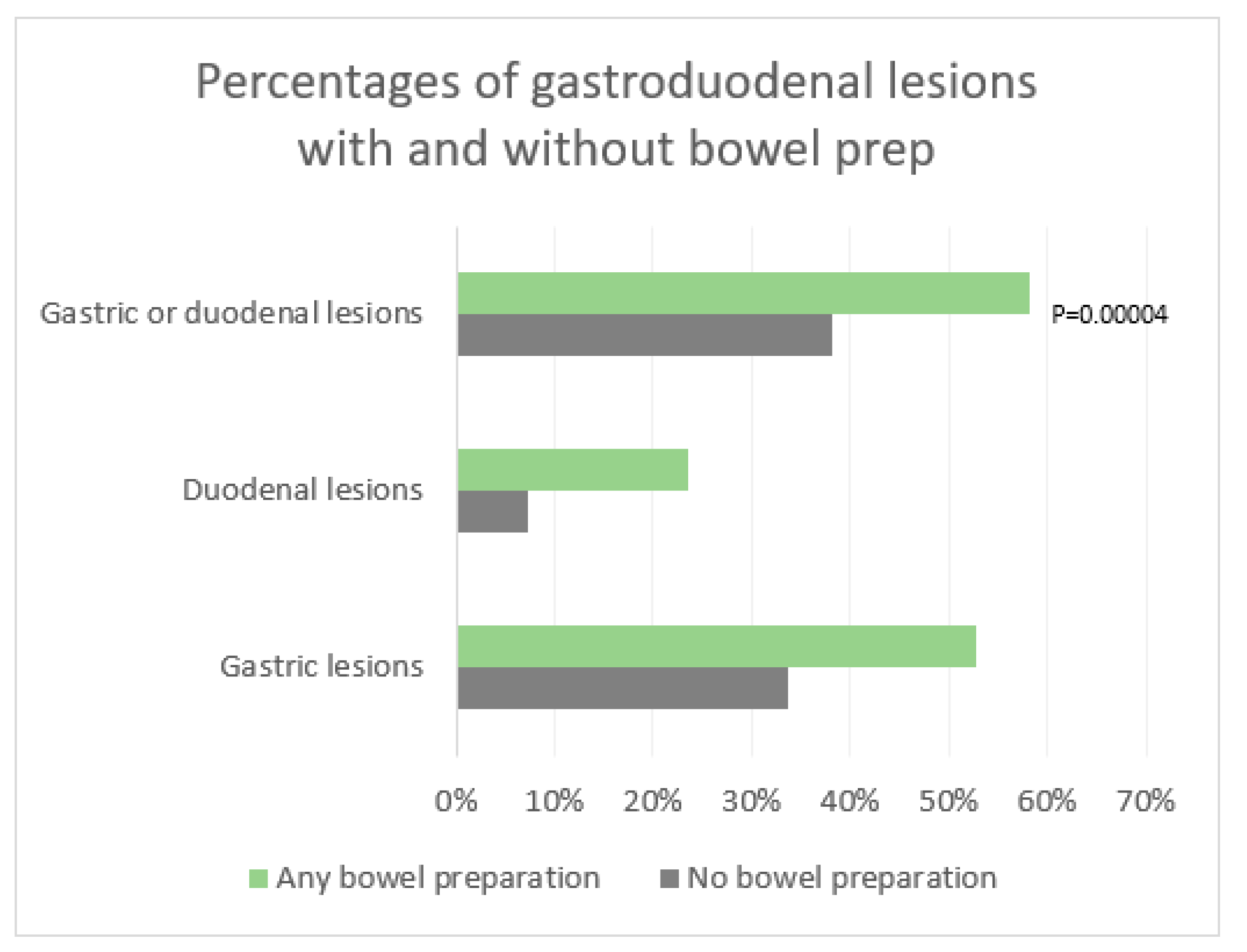

There was a significant difference between the rate of gastroduodenal lesions with prep and without prep. 58.3 % of patients who received bowel prep had gastric or duodenal findings, compared to 38.2 % of patients who did not receive any prep. Patients who received any prep were at significantly higher risk of having gastric or duodenal lesions with a relative risk (RR) of 1.53 (95% CI 1.19 - 1.94) and a p value of 0.00004 (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

The percentage of gastric lesions alone after any bowel preparation was 52.7% compared to 33.6% without any bowel prep with a statistically significant relative risk (RR) of 1.56 [95% CI 1.2 – 2] and a P value of 0.0001. Similarly, the relative risk (RR) of duodenal lesions alone was also statistically significant with 23.6% of patients having duodenal lesions after any bowel prep compared to 7.3% without any bowel prep, yielding a relative risk (RR) of 3.2 [95% CI 1.6 - 6.4] and a p value <0.0001. (

Table 3,

Figure 2).

Although the increase in duodenal lesions after prep, RR 3.2 [95% CI 1.6 - 6.3], was higher than the increase in gastric lesions, RR 1.56 [95% CI 1.2 – 2], this difference did not reach statistical significance (CI overlap).

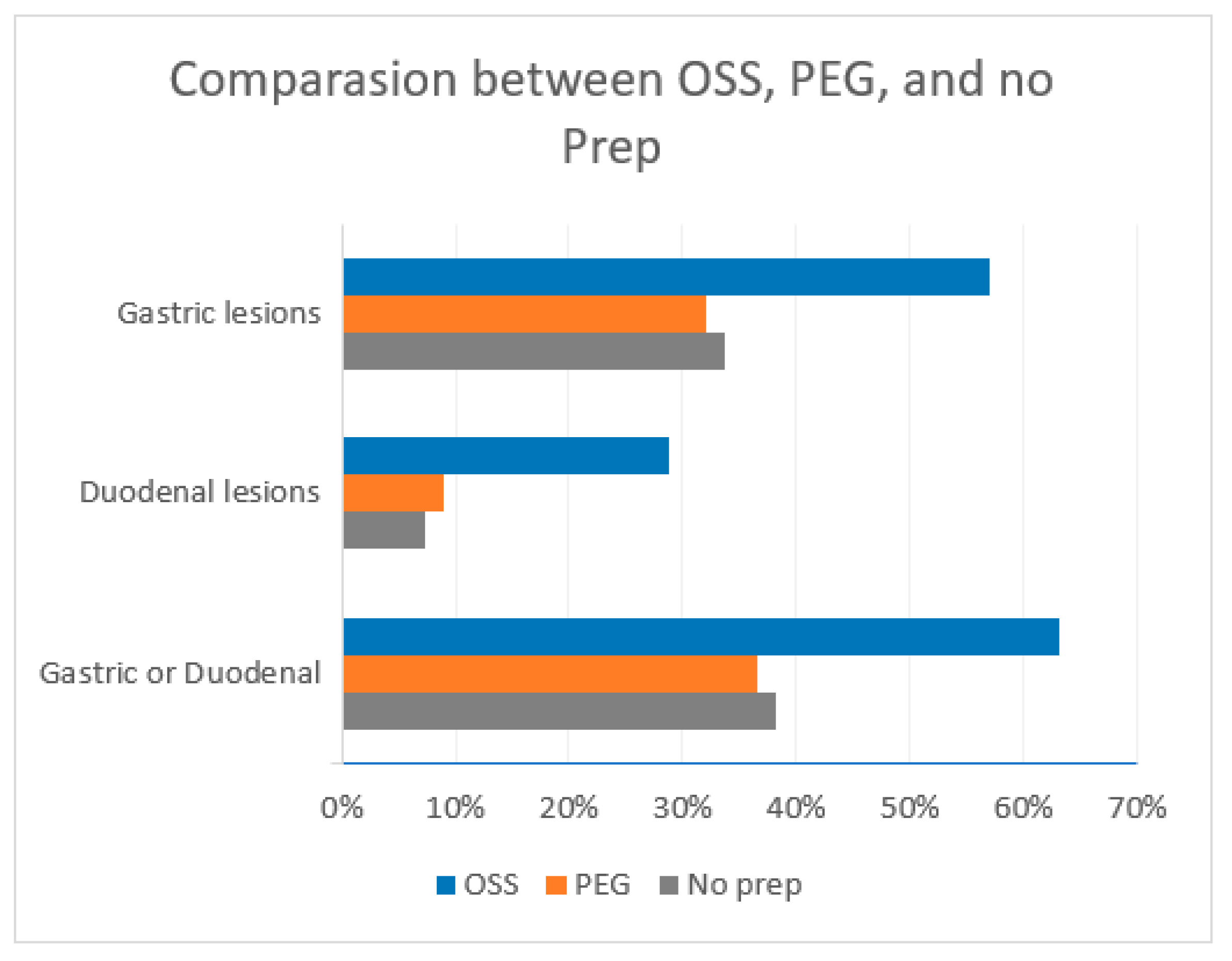

Among the prep studied, OSS and BIS groups were significantly associated with gastroduodenal lesions. 63.1 % of patients who received OSS had gastric or duodenal lesions compared to 38.2% of patients who did not receive any prep yielding a relative risk (RR) of 1.65 [95% CI 1.3 - 2.1] and a P value <0.0001. Bis alone was also highly associated with gastroduodenal lesions with 62.7% of patients having gastroduodenal lesions compared to 38.2 % of patients who did not receive prep yielding a relative risk (RR) of 1.64 (95% CI 1.25 - 2.15) and a P value of 0.0001.

This association was not found in PEG or PEG + Bis preparations. The prevalence of gastroduodenal lesions in the PEG group was 36.5 % compared to 38.2 % without prep, RR 0.96 (95% 0.7 - 1.3). Similarly, the prevalence of gastroduodenal lesions in the PEG + Bis group was also not statistically significant with a prevalence of 47.4 % compared to 38.2 % without prep, RR 1.24 (95% CI 0.82 - 1.87). (

Figure 3)

4. Discussion

Although it has been reported that some bowel preps may be associated with colonic lesions (1-11), this study is unique as it takes a different route and assesses the association between different bowel preps and gastric and duodenal lesions. The prevalence of gastroduodenal lesions in the general population varies among studies and have been reported as high as 31% in patients without any bowel preparation (12). In the present study, we found gastroduodenal lesions in 38.2% of patients who did not receive a prep, compared to 58.3% who did receive bowel preparation, a statistically significant increase compared to the no prep group (RR 1.5; 95% CI 1.19 - 1.94). These lesions included erythema, ulcers, erosions, or inflammation. It is important to interpret these results with caution, as our study did not take into account the lesions that might be caused by known risk factors (NSAIDs, H. Pylori, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.). This study was not randomized nor stratified by indication for capsule endoscopy, which may have introduced selection bias. The usage trends of different preparations changed over time, with no prep or PEG being more frequently used earlier in the study with a median procedure date March 2009. On the other hand, the OSS was used more frequently later in the study with a median procedure date March 2018. The definition of gastroduodenal lesions and the manner it was reported was not changed over the study period. Assuming that other conditions are equally distributed between both groups, this study yields an attributable risk of 20.1% that could be the result of bowel preparation.

The clinical implications of these observations may be significant even in the absence of major complications and lack of necessity for therapeutic interventions for these lesions. Understanding the etiology of gastroduodenal lesions is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. If the indication for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the time of colonoscopy is abdominal discomfort or bleeding, these gastroduodenal findings could be misinterpreted as the etiology of the indicated symptoms rather than the consequence of the preparation. This report describes findings unrelated to colonoscopy and upper gastrointestinal lesions proposed to be related to preparation. Endoscopists should be aware that preparations are associated with gastroduodenal lesions and should further pursue the etiology of upper gastrointestinal symptoms independent of a planned combined colonoscopy.

5. Conclusion

This study showed that patients who received bowel preparations had a significant increase in gastric and duodenal lesions. The clinical significance of these lesions remains undetermined. The increase was more pronounced in the duodenum. The frequency and prevalence of the findings varied but most preparations were associated with gastric and duodenal lesions. Endoscopists should be aware that bowel preparations are associated with gastroduodenal lesions to avoid misinterpretations and misdiagnosis of these lesions.

Author Contributions

Drs. Khouri and Moreno examined and collected data, analyzed and contributed to the manuscript. Dr. Di Palma conceptualized the project, collected data, analyzed results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Di Palma is a consultant medical director of Braintree Laboratories a part of Sebela Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have no conflicts.

References

- Anastassopoulos K, Farraye FA, Knight T, et al. A Comparative Study of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Following Use of Common Bowel Preparations Among a Colonoscopy Screening Population: Results from a Post-Marketing Observational Study. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61:2993-3006. [CrossRef]

- Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: Adverse event reports for oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 29, 15–28 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Chan A, Depew W. Vanner S. Use of oral sodium phosphate colonic lavage solution by Canadian colonoscopists: pitfalls and complications. Can J Gastroenterol 1997; 11, 334–338.

- Zwas FR, Cirillo N W, Ei-Serag HB, Eisen RN. Colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with oral sodium phosphate solution. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43:463-466.

- Hsu MH, Chang IW, Tai CM. White Spots in the Rectum. Gastroenterology 2016; 151: e15-e16.

- Driman DK. Preiksaitis HG Colorectal inflammation and increased cell proliferation associated with oral sodium phosphate bowel preparation solution. Hum Pathol 1998; 29:972–978.

- Watts DA, Lessells AM, Penman ID, Ghosh S. Endoscopic and histologic features of sodium phosphate bowel preparation-induced colonic ulceration: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55:584-587. [CrossRef]

- Rejchrt S, Bures J, Siroky M. A prospective, observational study of colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with orally administered sodium phosphate for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59:651-654. [CrossRef]

- Hagège H, Laugier R, Nahon S, et al. Real-life conditions of use of sodium phosphate tablets for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Endosc Int Open 2015; 3:e346-53. [CrossRef]

- Nam SY, Choi IJ, Park KW, et al. Risk of hemorrhagic gastropathy associated with colonoscopy bowel preparation using oral sodium phosphate solution. Endoscopy 2010; 42:109–113. [CrossRef]

- Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: Prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894-909. [CrossRef]

- Juanmartinene J, Sainz IF, Ollo BZ, et al. Gastroduodenal lesions detected during small bowel capsule endoscopy: incidence, diagnostic and therapeutic impact. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2018; 110:102-108. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).