1. Introduction

Many countries have multiple tiers of government, and various public goods are provided by different levels of government. Many public services are decentralized to subnational governments with intergovernmental transfers from the central government all over the world. Fiscal decentralization is also a policy change in developing countries that is frequently advocated by international agencies and bilateral donors. The decentralization of fiscal operations could affect the efficiency of public service delivery and fiscal sustainability by changing fiscal discipline. However, the literature that studies how the intergovernmental relationship associated with fiscal decentralization affects fiscal sustainability is relatively scarce, although sustainable fiscal operations are one of the main objectives of the government (Nakatani 2021). Therefore, this research studies how fiscal decentralization influences the probability of a sovereign debt crisis.

There are only two papers that study how fiscal devolution affects fiscal crises. Nakatani (2023a) recently studied the effects of fiscal decentralization on fiscal crises and fiscal indiscipline. He found that (i) spending decentralization to local governments increases the probability of a fiscal crisis, worsening local fiscal discipline; (ii) such an adverse decentralization effect on fiscal crisis probability is mitigated by a stronger rule of law; and (iii) vertical fiscal imbalance is negatively associated with fiscal crises. In another paper, Nakatani (2023b) found that over a threshold when approximately 16 percent of general government revenues are collected at the local level, countries are more likely to face a fiscal crisis.

However, these papers have several caveats. First, a potential endogeneity concern is not fully addressed. Second, they only studied the effects of fiscal decentralization to local governments (e.g., municipalities) but did not study the effects of decentralization to subnational governments (e.g., states, provinces). Third, these studies analyzed the effects of broad definitions of fiscal crises, which include credit events, large official financing, implicit domestic defaults, and loss of market confidence. However, no research has analyzed the effects of fiscal decentralization on sovereign debt crises. To overcome these three caveats, this paper studies the effects of multiple stages of fiscal decentralization on the probability of a sovereign debt crisis, utilizing an instrumental variable (IV) probit model to address the endogeneity problem.

Our results reveal that tax revenue decentralization is associated with a lower probability of a sovereign debt crisis. In contrast, expenditure decentralization is found to increase the probability of a sovereign debt crisis. These favorable effects of tax revenue decentralization and unfavorable effects of expenditure decentralization on sovereign debt crises are more evident in the case of decentralization to local governments relative to decentralization to subnational governments. Therefore, countries should be cautious about risks associated with fiscal devolution, particularly the contrasting impact of tax revenue and expenditure decentralization on the likelihood that sovereign debt crises occur.

2. Materials and Methods

Our data cover 82 countries from 1998 to 2019. The dependent variable is a dummy variable of sovereign debt crisis, taken from Moreno Badia et al. (2022). The explanatory variables include fiscal decentralization (tax revenue decentralization or expenditure decentralization) to subnational governments or local governments, GDP growth, current account balance (as a percent of GDP), exchange rates, government debt, interest costs, per capita income, inflation, banking crisis dummy, and currency crisis dummy. Fiscal decentralization data are taken from the IMF’s Fiscal Decentralization Dataset. The tax revenue decentralization variable is defined as the ratio of subnational or local governments’ tax revenues to the general government’s tax revenue. Similarly, expenditure decentralization is defined as a ratio of subnational or local governments’ expenditure to the general government’s expenditure. Economic variables are taken from the IMF’ World Economic Outlook Database. The GDP growth rate is an annual percent change in constant price GDP. Exchange rates are expressed as depreciation rates of exchange rates defined as national currency per current international dollar. Government debt is defined as general government gross debt as a percent of GDP. Interest costs are net interest expenses of the general government as a percent of GDP. Income per capita is calculated as the natural logarithm of GDP in constant price thousand international dollars per person. Inflation is the annual percentage change of average consumer prices. The dummy variables for banking and currency crises are taken from Nguyen et al. (2022).

We use the IV probit model to address potential endogeneity. We examine two instruments, i.e., political stability and size of land area, both of which are correlated with fiscal decentralization but exogenous to the sovereign debt crisis. For instance, when countries have large land areas, they tend to decentralize fiscal operations due to various transportation costs. In addition, it is easier for countries to decentralize fiscal operations when their political situation is stable. These data on instruments are collected from the World Development Indicators and Polity data series. The summary statistics of the data are shown in

Table 1.

3. Results

Table 2 shows the baseline estimation results using the IV probit model with the polity variable as an instrument. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is greater than 0.9, demonstrating outstanding discrimination of our empirical model.

The negative coefficients of tax revenue decentralization are statistically significant at the one percent level for both cases of decentralization to local governments and subnational governments. This result indicates that local and subnational tax autonomy reduces the probability of a sovereign debt crisis by improving local fiscal discipline. In contrast, the coefficients of expenditure decentralization to local governments and subnational governments are positive and statistically significant at the one percent level. This finding indicates that fiscal devolution on the expenditure side is associated with a higher probability of a sovereign debt crisis. This result of expenditure decentralization is in stark contrast to that of tax revenue decentralization.

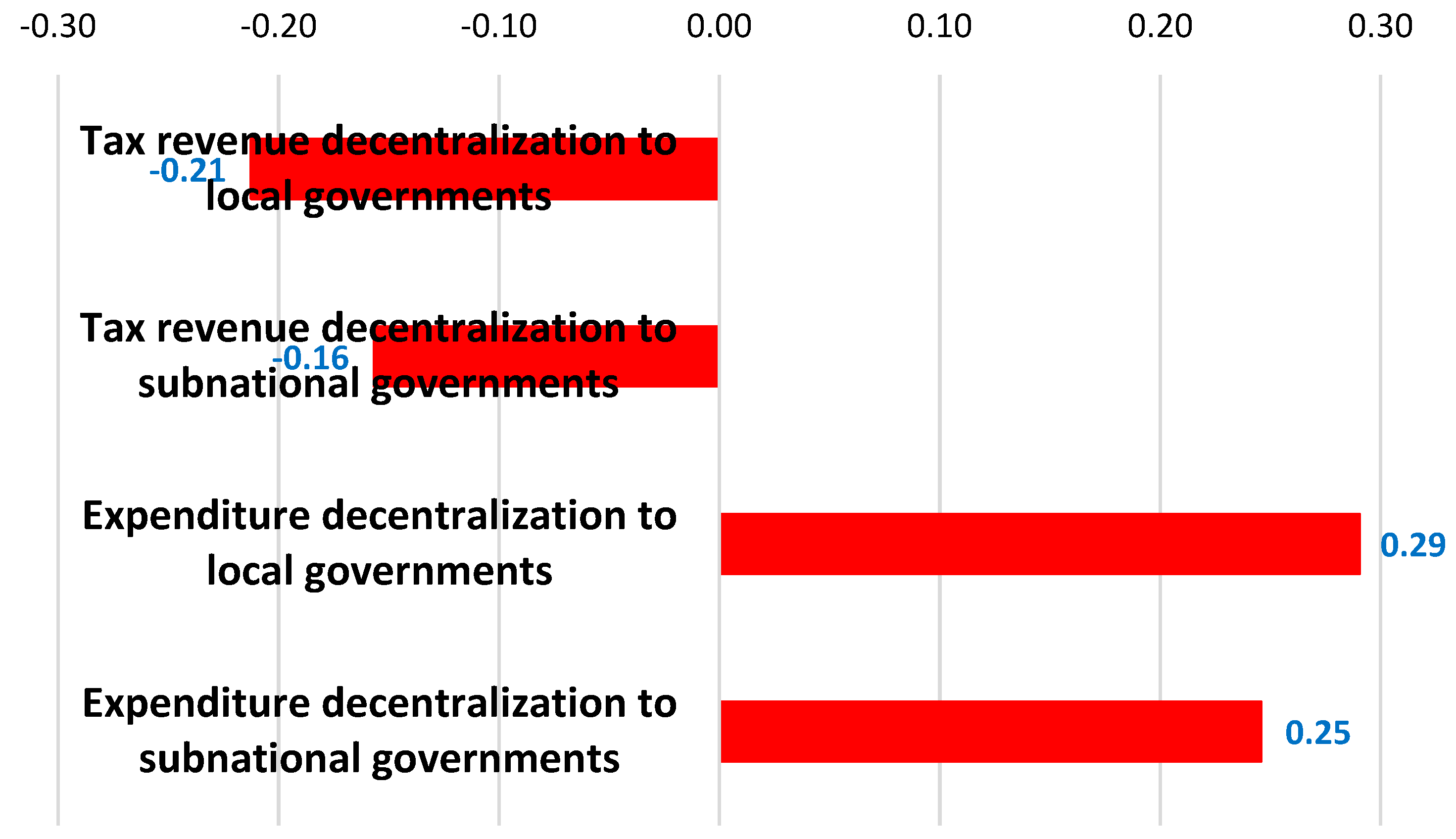

To compare the magnitude of the probability impacts of subnational/local decentralization on the revenue/expenditure sides, we multiply the estimated coefficients of each type of decentralization by one standard deviation of the corresponding variable in

Figure 1. We use within-country one standard deviation to study practically possible changes in the degree of decentralization in the same country rather than variations between countries. We have two main findings. First,

Figure 1 shows that the adverse effects of expenditure decentralization are larger than the favorable effects of tax revenue decentralization on the probability of a sovereign debt crisis, irrespective of levels of decentralization (local/subnational levels). Second, the probability impact of decentralization is always greater in the case of (tax revenue or expenditure) decentralization to local governments than decentralization to subnational governments. These are new findings, and no extant literature has explored them thus far.

The results of the robustness check using the size of land are shown in

Table 2. The robustness checks show that the coefficients of tax revenue and expenditure decentralization to local governments are highly statistically significant at the one percent level, although the coefficients of tax revenue and expenditure decentralization to subnational governments are only statistically significant at the ten percent level or nonsignificant. This outcome implies that fiscal devolution to local governments has significant effects on the probability of a sovereign debt crisis, while that to subnational governments may not. We will discuss the plausible reason behind this finding in the next discussion section.

Table 2.

Robustness Checks*

Table 2.

Robustness Checks*

| Decentralized Government Level |

Local |

Subnational |

Local |

|

|

Subnational |

|

| Tax revenue decentralization |

-9.7135*** |

-3.5508* |

- |

|

|

- |

|

| (0.6656) |

(2.1432) |

- |

|

|

- |

|

| Expenditure decentralization |

- |

- |

10.7263*** |

|

|

-3.0389 |

|

| - |

- |

(0.4915) |

|

|

(4.3142) |

|

| GDP growth |

0.0062 |

-0.0320 |

-0.0340* |

|

|

-0.0240 |

|

| (0.0122) |

(0.0210) |

(0.0190) |

|

|

(0.0262) |

|

| Current account balance |

0.0131*** |

0.0122 |

0.0023 |

|

|

-0.0015 |

|

| (0.0044) |

(0.0100) |

(0.0057) |

|

|

(0.0095) |

|

| Exchange rates |

3.9954*** |

5.3077*** |

-2.2482 |

|

|

4.3927* |

|

| (1.2602) |

(2.0191) |

(2.5372) |

|

|

(2.3960) |

|

| Government debt |

0.0153*** |

0.0129*** |

-0.0059 |

|

|

0.0065* |

|

| (0.0015) |

(0.0021) |

(0.0037) |

|

|

(0.0038) |

|

| Interest cost |

-0.2445*** |

-0.0482 |

0.1988*** |

|

|

-0.0634 |

|

| (0.0302) |

(0.0645) |

(0.0515) |

|

|

(0.0793) |

|

| Income per capita |

0.0227 |

-0.6237* |

-0.9169* |

|

|

-0.4402 |

|

| (0.1954) |

(0.3606) |

(0.4959) |

|

|

(0.8559) |

|

| Inflation |

0.0073 |

-0.0207 |

-0.0169 |

|

|

-0.0250 |

|

| (0.0116) |

(0.0199) |

(0.0176) |

|

|

(0.0212) |

|

| Banking crisis |

0.2616** |

0.3240 |

-0.0926 |

|

|

0.5366 |

|

| (0.1254) |

(0.2437) |

(0.3217) |

|

|

(0.3339) |

|

| Currency crisis |

0.2204 |

0.4154 |

-0.0036 |

|

|

0.4486 |

|

| (0.2291) |

(0.3700) |

(0.3360) |

|

|

(0.3798) |

|

| Number of observations |

1,422 |

1,435 |

882 |

|

|

895 |

|

| Area under ROC curve |

0.9275 |

0.9283 |

0.9366 |

|

|

0.9395 |

|

| Log likelihood |

1179.79 |

768.92 |

682.99 |

|

|

513.20 |

|

| Wald chi (10) |

1283.77*** |

121.02*** |

627.09*** |

|

|

77.92*** |

|

| Wald test of exogeneity |

9.20** |

3.08* |

1.72 |

|

|

1.20 |

|

4. Discussion

We have found three main findings in the previous section. First, we found that the probability impact of expenditure decentralization is greater than that of tax revenue decentralization. This finding is explained by the fact that expenditure decentralization to local and subnational governments could lead to overspending of these governments when they expect bail-out by the central government, which is called the soft budget constraint problem (Kornai 1986). This overspending in turn increases the budget deficit (Rodden 2002) and hence subnational borrowing (Foremny et al. 2017), which eventually leads to higher sovereign spread (Eichler and Hofmann 2013) and a sovereign debt crisis. Our outcomes show that such effects on local fiscal indiscipline are larger than the disciplinary effects of local tax autonomy. In other words, an absence of proper commitment to tax for spending (higher vertical fiscal imbalance) would trigger the moral hazard problem of local governments by relying on transfers financed by common pool resources (Nakatani et al. 2023).

The second finding is that the effects of fiscal devolution are larger when countries decentralize tax revenue collection or spending to local governments than to subnational governments. This can be attributed to the practice that local governments lack economies of scale more than subnational governments, as their sizes are smaller than subnational ones. Economies of scale are the situation in which an increase in size leads to more efficient operation with higher productivity by lowering costs (Nakatani 2023c). Due to the small size of each local government, local decentralization benefits fewer economies of scale than subnational decentralization. Our results corroborate the recent findings of Nakatani et al. (2022), who found that the marginal effects of decentralizing education expenditure to subnational governments on educational outcomes are always higher than those of local decentralization.

Finally, our robustness check analysis shows that the effects of fiscal devolution are significant when fiscal operations are decentralized to local governments, while this may not be the case for decentralization to subnational governments, depending on the instrument we use. Therefore, fiscal authorities should be mindful of the favorable and unfavorable effects of decentralization on crisis probability, especially when they tend to decentralize tax revenue collection and expenditure operations to the lowest level of government.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this analysis are found on the IMF websites.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Guest Editor Professor Kudret Topyan for granting me free publication of my article in this special issue.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views in this article are the authors’ and do not reflect that of the institution to which he belongs.

References

- (Eichler and Hofmann 2013) Eichler, Stefan, and Michael Hofmann. 2013. Sovereign default risk and decentralization: Evidence for emerging markets. European Journal of Political Economy 32: 113-134. [CrossRef]

- (Foremny et al. 2017) Foremny, Dirk, Agnese Sacchi, and Simone Salotti. 2017. Decentralization and the duration of fiscal consolidation: Shifting the burden across layers of government. Public Choice 171: 359-387. [CrossRef]

- (Kornai 1986) Kornai, Janos. 1986. The soft budget constraint. Kyklos 39 (1): 3-30. [CrossRef]

- (Moreno Badia et al. 2022) Moreno Badia, Marialuz, Paulo Medas, Pranav Gupta, and Yuan Xiang. 2022. Debt is not free. Journal of International Money and Finance 127: 102654. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani 2021) Nakatani, Ryota. 2021. Fiscal rules for natural disaster- and climate change-prone small states. Sustainability 13 (6): 3135. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani 2023a) Nakatani, Ryota. 2023a. Fiscal crises, decentralization, and indiscipline. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 459–478. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani 2023b) Nakatani, Ryota. 2023b. Revenue decentralization and the probability of a fiscal crisis: Is there a tipping point for adverse effects? Public Finance Review forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani 2023c) Nakatani, Ryota. 2023c. Productivity drivers of infrastructure companies: Network industries utilizing economies of scale in the digital era. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 94 (4): 1273-1298. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani et al. 2022) Nakatani, Ryota, Qianqian Zhang, and Isaura Garcia Valdes. 2022. Fiscal decentralization improves social outcomes when countries have good governance. IMF Working Paper 22/111. [CrossRef]

- (Nakatani et al. 2023) Nakatani, Ryota, Qianqian Zhang, and Isaura Garcia Valdes. 2023. Health expenditure decentralization and health outcomes: The importance of governance. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- (Nguyen et al. 2022) Nguyen, Thanh Cong, Vítor Castro, Justine Wood. 2022. A new comprehensive database of financial crises: Identification, frequency, and duration. Economic Modelling 108: 105770. [CrossRef]

- (Rodden 2002) Rodden, Johathan. 2002. The dilemma of fiscal federalism: Grants and fiscal performance around the world. American Journal of Political Science 46 (3): 670-687. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).