1. Introduction

The current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has been ongoing for more than two years, and continues to challenge the available science and technology worldwide to combat COVID-19 infection. Globally, as of 8

th November 2023, there were 771,820,937 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,978,175 deaths deaths, as reported to the WHO [

1]. The prevailing SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in the market have been developed using either mRNA technology [

2,

3], adenovirus vectors[

4], whole inactivated virus [

5,

6], or as a protein-based subunit vaccine [

7]. Although the existing vaccines have successfully elicited a robust immune response, this success is hampered by the hurdles of a slow supply chain, the need for storage at extremely low temperatures, and high cost. These factors limit the use of the existing vaccines across all the nations in the world.

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped virus that depends on the spike (S) glycoprotein for binding and entry of host cells. The S protein exists as a homotrimer on the viral envelope, where binding of the receptor binding domain (RBD) to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2) initiates cell entry. Antibodies targeting spike, particularly its RBD, can efficiently neutralize the virus; therefore, it is the primary target for neutralizing antibodies in the current vaccines [

8]. Due to the complexity of producing the large protein trimer, there has been much interest in using the recombinantly expressed RBD portion of the spike as a vaccine target [

11,

12,

13].

Although there have been several efforts to develop RBD-based subunit vaccines, these have been hindered due to the poor immunogenicity of the RBD protein component [

9]. In a subunit vaccine, an adjuvant is often required to engage the innate immune system due to the absence of the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that would be present in natural infection. Additionally, adjuvants can help reduce the needed dose of antigen, which is of great help during a pandemic when large-scale vaccinations are required. This was demonstrated during the 2009 flu pandemic, where H1N1 vaccines adjuvanted with adjuvant system 03 (AS03) generated higher antibody titers compared to the non-adjuvanted vaccines that contained a higher dose of antigen [

10]. Additionally, subunit vaccines are relatively easy to manufacture, inexpensive, highly effective, generally do not require stringent storage conditions, and have a good safety profile.

Selection of the adjuvant is critical, as it allows for the tailoring of the immune response to be most effective against the specific pathogen [

11,

12]. Examples of adjuvants approved for human use in licensed vaccines include Algel-Imidazoquinoline [

13], alhydrogel [

14], CpG 1018 [

14], AS01 [

15,

16], AS03 [

10,

16] AS04 [

15,

17], MF59 [

15,

17], and Matrix-M [

7]. Most approved adjuvants activate either individual or combinations of pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) to drive stronger humoral and/or cell-mediated immunity [

11,

15,

18,

19]. One well-studied class of PRRs are toll-like receptors (TLR), which comprise an evolutionarily conserved receptor family capable of detecting and responding to various microbial challenges [

20,

21].

Human TLR7 receptors are present within plasmacytoid dendritic cell and B cell endosomes, while TLR8 is found more widely distributed in myeloid cells [

22]. These receptors both recognize single-stranded RNA, as well as a number of synthetic oxoadenines and imidazoquinolones. These TLRs signal through myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) to produce type I interferons and the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, MIP-1α, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-12 [

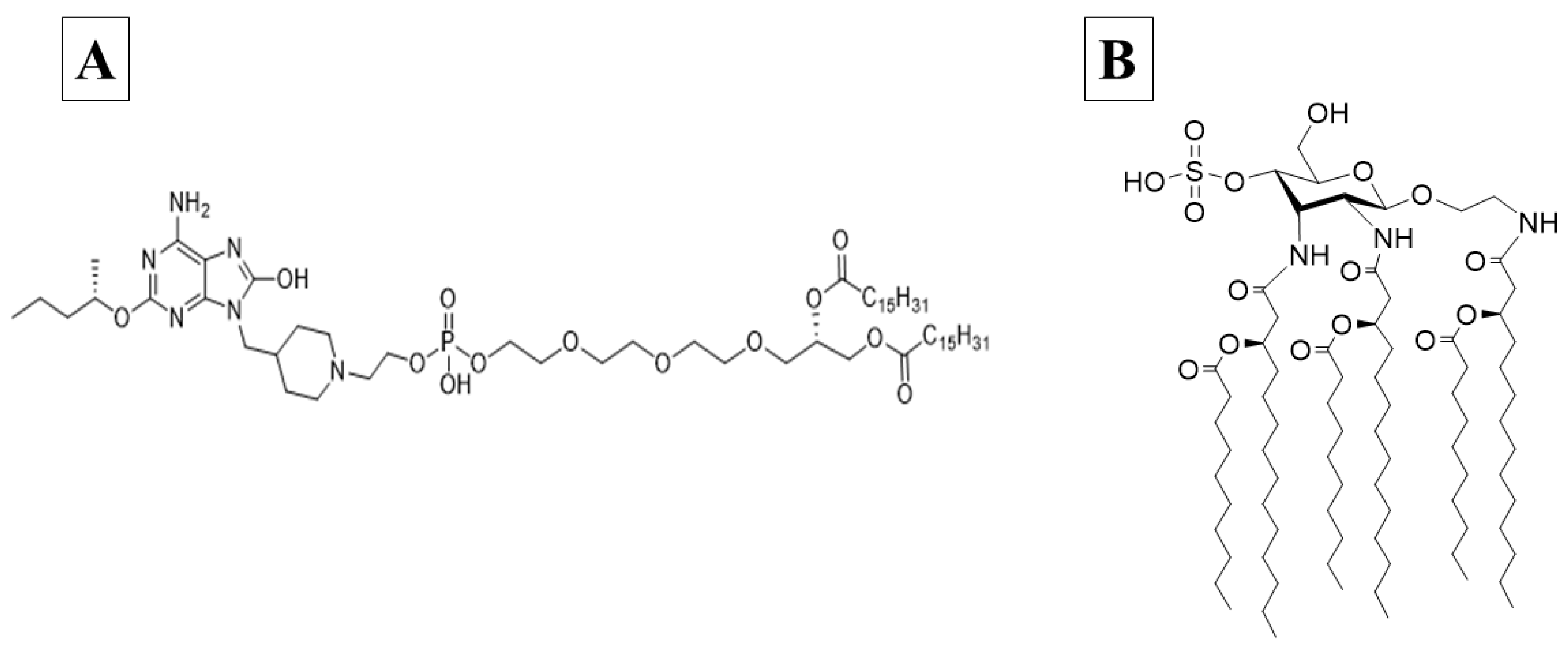

20]. INI-4001 is a novel lipidated TLR7/8 ligand with an oxoadenine core (

Figure 1a), designed to effectively signal through both TLR8 and TLR7, and easily formulated in liposomes, emulsions or by adsorption to alum, with reduced side effects previously associated with the rapid systemic distribution of core TLR7/8 ligands [

23]. The success of subunit vaccines that employ TLR agonists is demonstrated by Heplisav-B™ (Dynavax), Shingrix, Mosquirix, Fendrix, and Cervarix [

16].

Human TLR4 receptors are present on the cell surface of antigen-presenting cells and recognize bacterial cell wall components like lipopolysaccharide. Their activation produces multiple inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12, through the initiation of MyD88 and TIR domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon-beta (TRIF)-dependent pathways [

21,

24]. INI-2002 is a novel synthetic TLR4 ligand derivatized from lipopolysaccharide (

Figure 1b). The promise of using a TLR4 agonist as a vaccine adjuvant has been demonstrated by the approval of GlaxoSmithKline’s Adjuvant System 04, an adjuvant consisting of the TLR4 agonist MPL (3-O-desacyl4’-monophosphoryl lipid A) adsorbed onto a particulate form of aluminum salt. It is licensed for use in two human vaccines, Cervarix

® and Fendrix

®, and was shown not only to boost the antigen-specific antibody response, but also promote epitope broadening [

25,

26].

For decades aluminum salts have been used successfully as adjuvants in subunit vaccines, boosting antibody titers and promoting a Th2-mediated immune response through adsorption to antigens [

11,

27]. Aluminum salts have many benefits that make them ideal adjuvants for a pandemic vaccine: a strong safety profile, a long history of regulatory approval, low cost, good stability, and ease of manufacture, storage, and distribution. Alhydrogel (AH) and Adju-Phos (AP) are both aluminum-containing salts, composed of a semi-crystalline form of aluminum oxyhydroxide and amorphous salt of aluminum hydroxyphosphate, respectively [

27]. We made several aluminum salt formulations that can efficiently adsorb and co-deliver INI-4001 and/or INI-2002 with RBD antigen. Our lab has previously demonstrated that co-delivery of TLR7/8 and TLR4 ligands within a liposome increased IgG2a antibody titers and skewed the immune response to an influenza antigen towards Th1 [

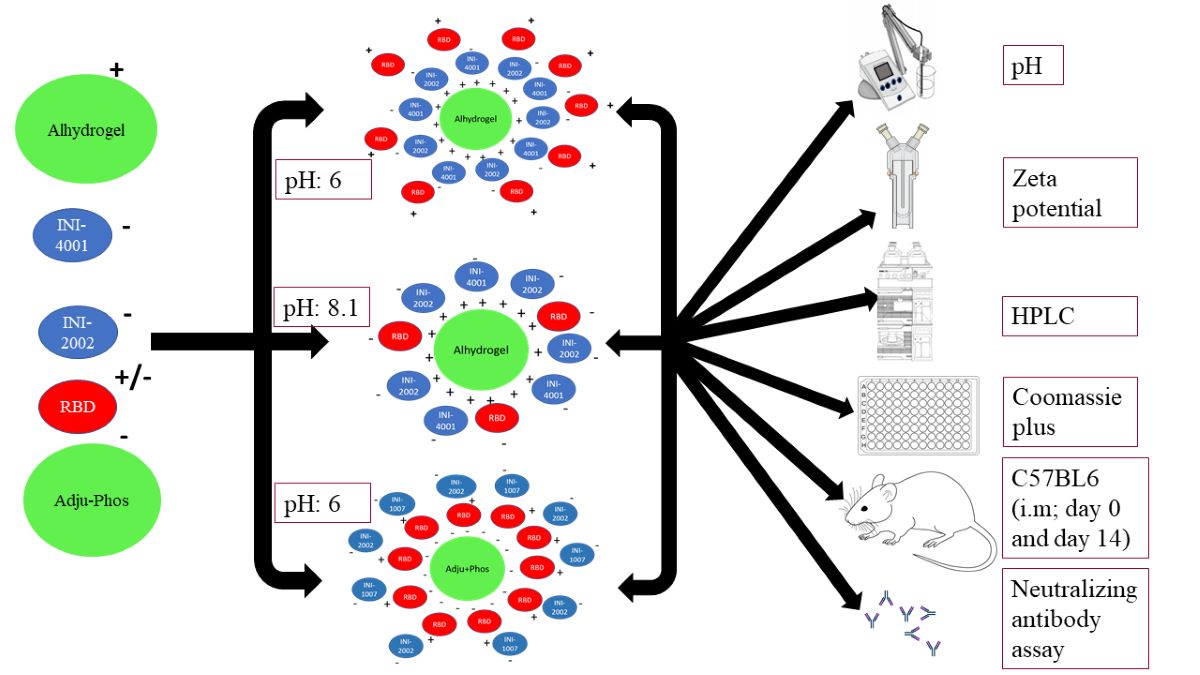

28]. In line with that success, we developed subunit SARS-CoV-2 vaccines using RBD as the antigen, co-delivered with an aluminum salt alone or in combination with a TLR7/8 agonist (INI-4001) and/or a TLR4 agonist (INI-2002). These vaccine formulations were tested in C57BL/6 mice for their ability to enhance immunity to RBD. We measured the anti-RBD serum antibody titers and evaluated their ability to block the binding of spike RBD and the full-length spike trimer to hACE2. Additionally, we measured the cytokines produced by antigen-specific T cells to determine the profile of the cellular response. We found that co-delivery of RBD with INI-4001, and/ or INI-2002 on AH efficiently skewed the immune response towards Th1 and generated strong neutralizing antibodies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antigens and adjuvants

2-[(R)-3-decanoyloxytetradecanoylamino]ethyl 2,3-di-[(R)-3-decanoyloxytetradecanoylamino]-2,3-dideoxy-4-O-sulfoxy-β-D-allopyranoside (INI-2002) was synthesized as previously described [

29]. UM-4001 was synthesized by phospholipidation of 6-amino-2-butoxy-9-[(1-hydroxyethyl-4-piperidinyl)-methyl]-7, 9-dihydro-8H-purin-8-one [

30] using the published phosphoramidite method [

31]. AH and AP were purchased from InvivoGen. RBD antigen was synthesized by expression in HEK-293 cells and subsequent purification [

32].

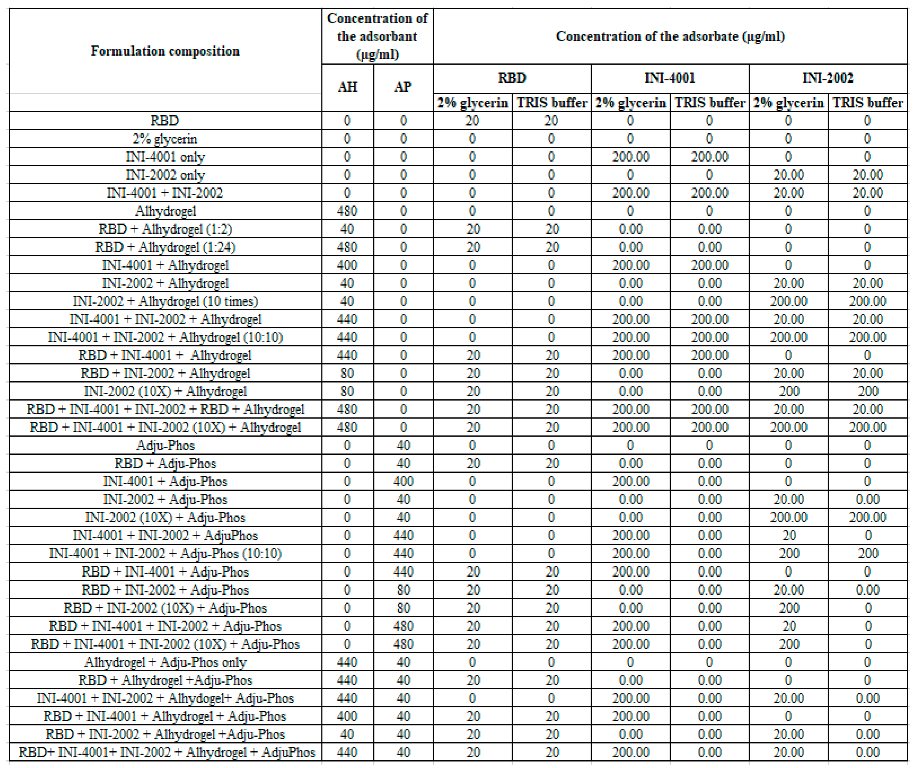

2.2. Adsorption of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to preformed aluminum salts

Aqueous formulations of INI-4001 and INI-2002 at 2 mg/ml were prepared by solubilizing the respective ligand in 2% glycerin using a bath sonicator (FB11201, Fisherbrand) for 3 hours or 15 minutes, respectively, at a temperature <35°C. The formulations were sonicated until the particle size was below 200 nm. The aqueous formulations were sterile-filtered using a 13 mm Millex GV PVDF filter with a pore size of 0.22 μm (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA).

Prior to the adsorption experiments, AH and AP were diluted to 1 mg/ml using the corresponding formulation vehicle. Adsorption experiments of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to AH were performed using two formulation vehicles, 2% glycerin or 10 mM TRIS buffer of pH 8.1 (referred to as TRIS buffer hereafter). Adsorption experiments of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to AP were performed using 2% glycerin. The weight ratio of aluminum salt (AH or AP) to the sum of antigen and adjuvant (INI-4001 and/or INI-2002) was 2:1. A series of formulations were prepared by mixing the required amounts of INI-4001, INI-2002, RBD, AH, AP, and formulation vehicle by end-over-end rotation at room temperature for 1h [

33]. The compositions of the formulations are described in

Table 1.

2.3. Measurement of zeta potential and pH of the adsorbed formulations

Zeta potential was measured using Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) by a disposable capillary cell following the manufacturer’s instructions. A 1:10 dilution in the respective formulation vehicle was used for all the samples. The pH of the formulations was measured using an Accumet AB150 pH meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an InLab Micro probe (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) after a three-point calibration using pH 4.01, 7.00, and 10.01 standards. All the measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4. Visualization of AH and AP formulations by cryo-TEM

AH and AP formulations adsorbed with INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD were vortexed for 2 minutes, and 3 µl of the suspensions were pipetted onto glow-discharged (120 secs 15 mAmp, negative mode) copper Quantifoil holey carbon support grids (Ted Pella 658-300-CU) and vitrified in liquid ethane using a Mark IV Vitrobot (Thermo Fisher, Hillsboro, OR). The conditions utilized for the cryopreservation were 100% humidity, blot force -15, and blotting time 3 seconds. Low-dose conditions were used to acquire images on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Glacios cryo-TEM at 200 kV with a K3 Gatan direct electron detector. Cryo-EM images were collected with a defocus range of 2.5 µm.

2.5. Analytical method to simultaneously analyze INI-4001 and INI-2002

Simultaneous quantitation of INI-4001 and INI-2002 was performed using a Waters Acquity Arc RP-HPLC system equipped with a 2998 PDA detector. Separation was performed using a Waters CORTECS C18+ 3.0x50mm 2.7 µm column at 40°C. Mobile phases comprising 10mM ammonium formate at pH 3.2 with acetonitrile and water (60:40 ratio) were used as mobile phase A and 10mM ammonium formate at pH 3.2 with acetonitrile and IPA (50:50 ratio) was used as mobile phase B. The gradient (0-0.5 min. 60% A ; 6-7 min. 100% B; 7.1-8.5 min 60% A) was run for 8.5 minutes at 1.5 ml/min. The absorbance of INI-4001 and INI-2002 was measured at 278 nm and 210 nm, respectively. All the samples were quantitated by peak area based on extrapolation from a six-point dilution series of the corresponding standards in methanol.

2.6. Method to determine free INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD with aluminum salts

To detect the unbound INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD on the aluminum salt formulations, 100 µL of the formulation was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 19,400 rcf (5417C, Eppendorf) to form sediment of aluminum salt at the bottom. The supernatants were carefully collected and analyzed for the amount of free INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD. The amount of INI-4001 and INI-2002 in the supernatant samples were analyzed using the RP-HPLC method mentioned above. A Coomassie plus kit was used by following the manufacturer’s protocol to quantify the amount of RBD in the supernatants. The percentage of RBD adsorbed on AH and AP was estimated relative to RBD recovered in the control samples.

2.7. In vivo studies

Eight- to ten-week old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were group housed under a standard 12/12 hour light/dark cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. Animal studies were carried out in an OLAW and AAALAC accredited vivarium in accordance with University of Montana IACUC guidelines. Mice were vaccinated with 50µl in one gastrocnemius (calf) muscle using a 27G needle, with 8 mice per experimental group, and 5 mice in the vehicle-only control group. Vaccines consisted of 1µg of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD, along with 24µg per mouse of Alhydrogel (Invivogen) or Adju-phos (Invivogen) and/or 10µg of the TLR4 agonist INI-2002 (Inimmune Corp, Missoula, MT), 10µg of the TLR7/8 agonist INI-4001 (Inimmune Corp, Missoula, MT) or both. Mice were given an identical booster vaccine 14 days later, and blood was sampled by submandibular collection 28 days after the booster. Blood samples were allowed to coagulate in BD Microtainer serum separator tubes, and the serum was collected following a 5 minute centrifugation at approximately 16,000 rcf and stored at -20˚C until assayed. A second booster was administered on day 42 (28 days post-secondary), and mice were sacrificed 5 days later to assess the functional phenotype of RBD-specific T cells. The spleens and draining (inguinal and popliteal) LNs from the side of injection were collected in cold HBSS. Organs were manually disassociated into single cell suspensions, and red blood cells were lysed in the spleen samples by a 5 minute incubation in room temperature red blood cell lysis buffer (Biolegend), followed by washing in excess cold HBSS. Cell samples were resuspended in cold HBSS and counted using a Cellaca MX (Nexelcom Biosciences). The cells were resuspended to the desired concentration in complete RPMI (RPMI-1640, Gibco/ThermoFisher) containing 2mM L-glutamine, 100U/ml penicillin, 100U/ml streptomycin (Cytivia/Hyclone), 550µM b-mercaptoethanol (Gibco/Thermo Fisher), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Cytivia/Hyclone)). 5x106 spleen and 2x106 LN cells from individual mice were cultured in flat-bottom 96-well TC-treated plates for approximately 72 hours in the presence of 10µg/ml RBD protein. The plates were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 400xg, and the cell supernatant was recovered and stored at -20˚C until assayed for cytokines.

2.8. Serum ELISAs for quantification of anti-RBD antibodies

Serum samples were analyzed by ELISA for RBD-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c antibody titers. Nunc MaxiSorp 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated overnight at RT with 100µl per well of RBD antigen at 5µg/ml (for IgG) or 2.5µg/ml (for IgG1 and IgG2c) in PBS. The plates were washed three times with PBS + 0.5% Tween-20 (PBS-T), and blocked with 200µl of SuperBlock (ScyTek Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) for 1 hour at 37˚C. Serial dilutions of each serum sample were made in EIA buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Tween-20, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline) according to the expected antibody response. Blocking solution was removed, and plates were incubated with diluted serum for 2 hours at 37˚C, followed by washing three times with PBS-T, and incubation with anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:3000), IgG1-HRP (1:5000), or IgG2c-HRP (1:5000) secondary antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) in EIA buffer for 1 hour. After three washes, secondary antibodies were detected by addition of TMB Substrate (KPL SureBlue™, SeraCare, Milford, MA, USA) for 20 minutes, followed by stopping the reaction by addition of H2SO4. The SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to measure absorbance at 450nm, and the antibody titers are reported as the dilution factor required to achieve an optical density of 0.3. Measurements below the limit of detection for sera diluted at 1:50 were assigned a value of 1.0 for analysis purposes.

2.9. T cell cytokine assessment

The concentrations of IFNγ, IL-5, and IL-17A in the supernatants collected from spleen and LN cells isolated from individual animals following stimulation with RBD for 72 hours was assessed using a U-Plex assay (multiplex ELISA) by MesoScale Discovery (MSD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.10. Surrogate neutralization assay

Serum samples were assayed for the ability to inhibit the binding of soluble human ACE2 to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) and to the trimerized protein ectodomain (Spike) as a surrogate for viral neutralization capability. Sera from individual mice were assayed with the V-PLEX SARS-CoV-2 ACE2 Panel 6 Kit (K15436U, Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA), using the supplied standard antibody and according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, this kit contains RBD and Spike proteins immobilized to plates that allow for the detection of bound human ACE2 protein through electrochemiluminescence using the MESO QuickPlex SQ 120 imager (Meso Scale Diagnostics). A standard monoclonal Ab that binds to RBD and efficiently blocks its binding to human ACE2 was used as a standard, and sample data are reported as the µg/ml concentration of the standard antibody that gives equivalent blocking of binding to RBD or Spike.

2.11. Statistics

RBD-specific antibody titers, antigen-specific cytokine concentrations, and surrogate neutralization assay results were plotted and the statistics calculated using Prism (GraphPad Software, LLC). For RBD-specific antibody titers and surrogate neutralization assays, significant differences between groups was determined using a Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA of the log-transformed data with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test. For cytokine concentrations, a one-way ANOVA was performed on the log-transformed data, with a Tukey post-test. Asterisks indicate statistical differences between relevant groups; *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

3. Results and discussion

Alum promotes recruitment of dendritic cells and macrophages to the draining lymph nodes; the adsorption and co-delivery of antigens and TLR ligands to aluminum salts is crucial for the enhancement of immunogenicity [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Thus, we sought to develop aluminum salt adsorbed formulations to facilitate the co-delivery of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD.

3.1. Pre-formulation studies

Pre-formulation studies were performed to optimize the amount of aluminum salt (AH or AP) needed to fully adsorb INI-4001, INI-2002 or RBD as well as the duration of mixing required to achieve complete adsorption. The results indicated efficient adsorption of INI-4001, INI-2002 or RBD to aluminum salt at a 1:2 weight ratio (not shown). Hence, this weight ratio was used for all the subsequent formulation studies reported herein. Although complete adsorption was achieved in 30 minutes, the duration of mixing was increased to 60 minutes to ensure adsorption equilibrium had been reached.

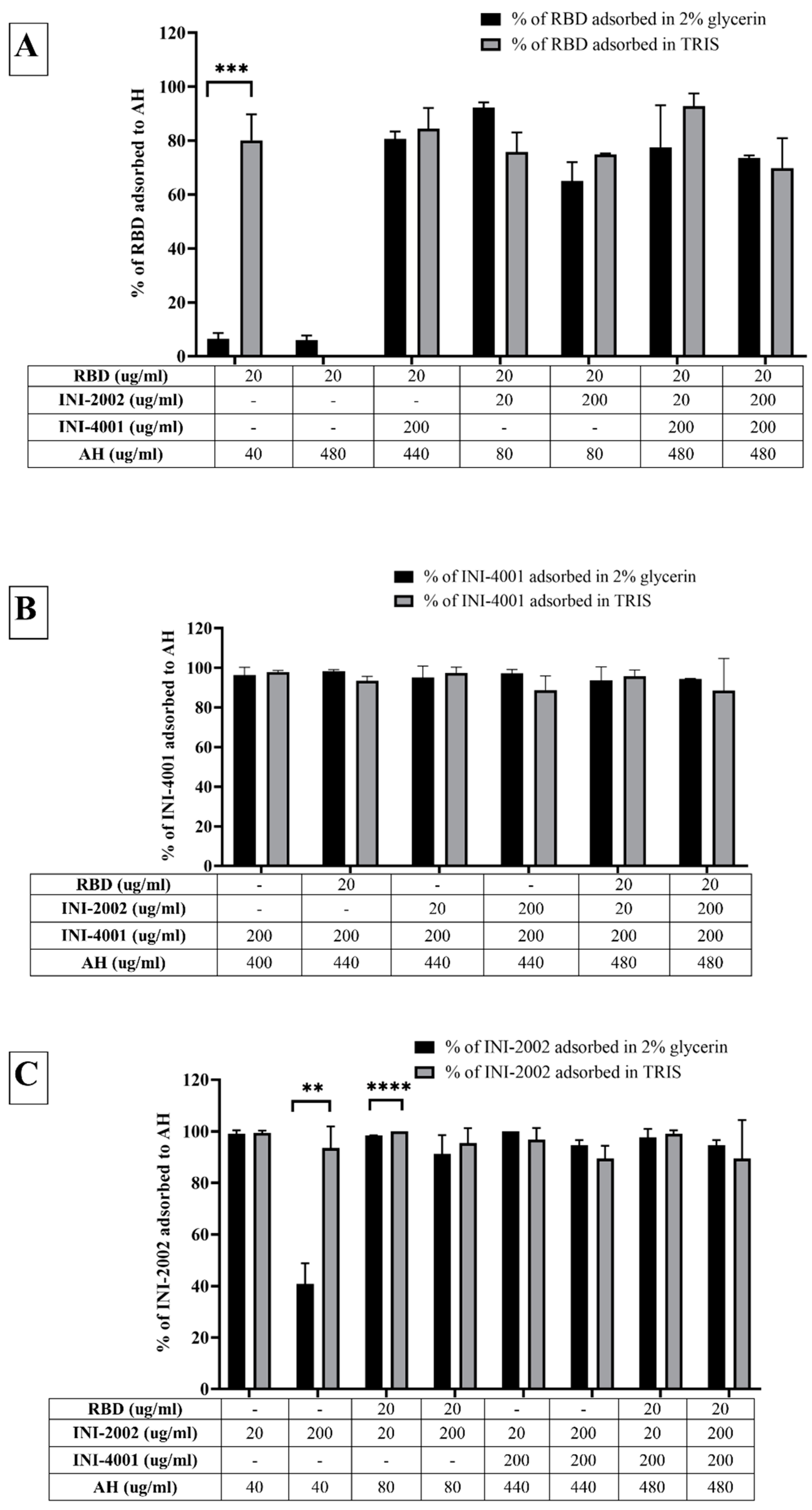

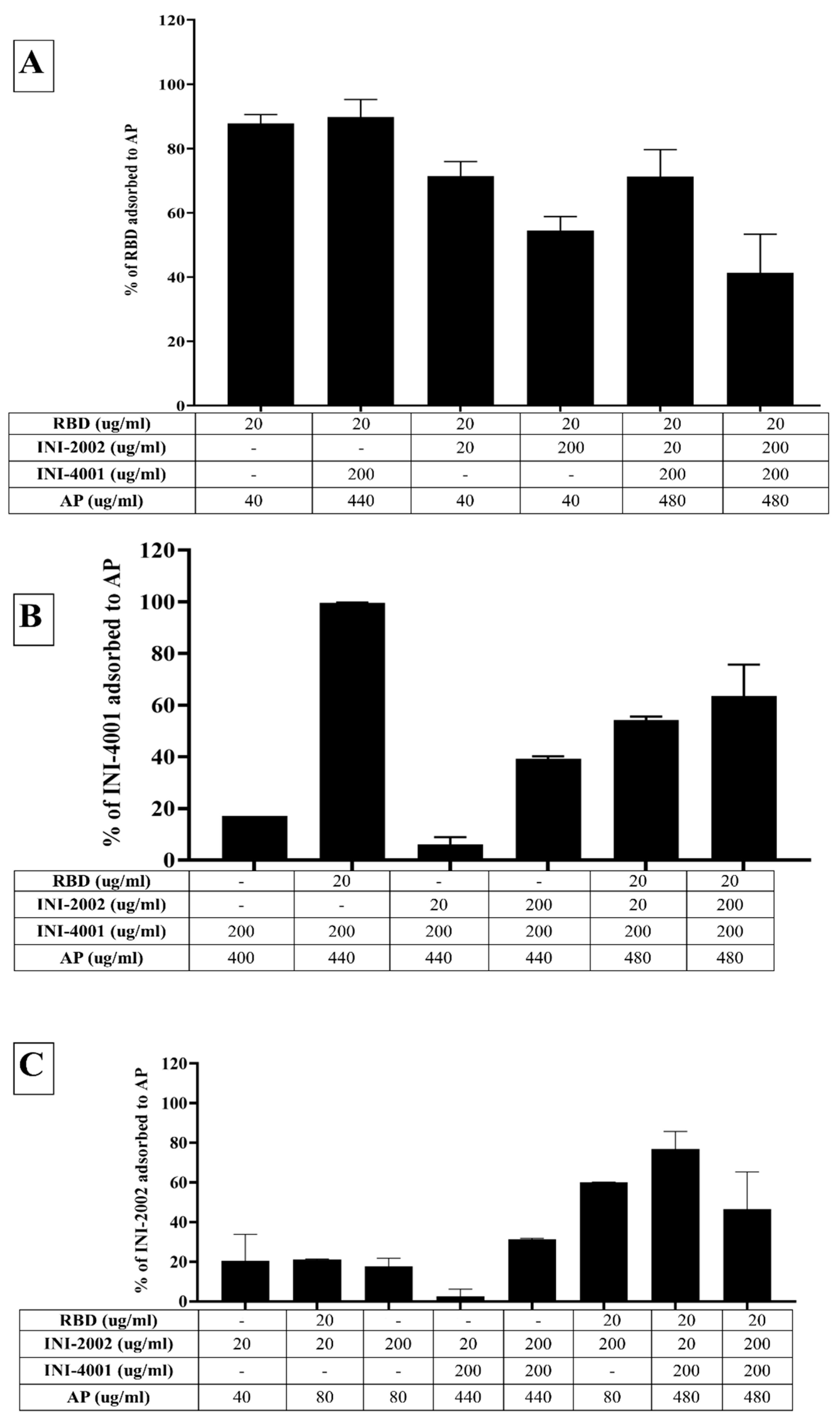

3.2. Adsorption characteristics of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to AH

The adsorption results of the TLR ligands INI-4001 and INI-2002 to AH in

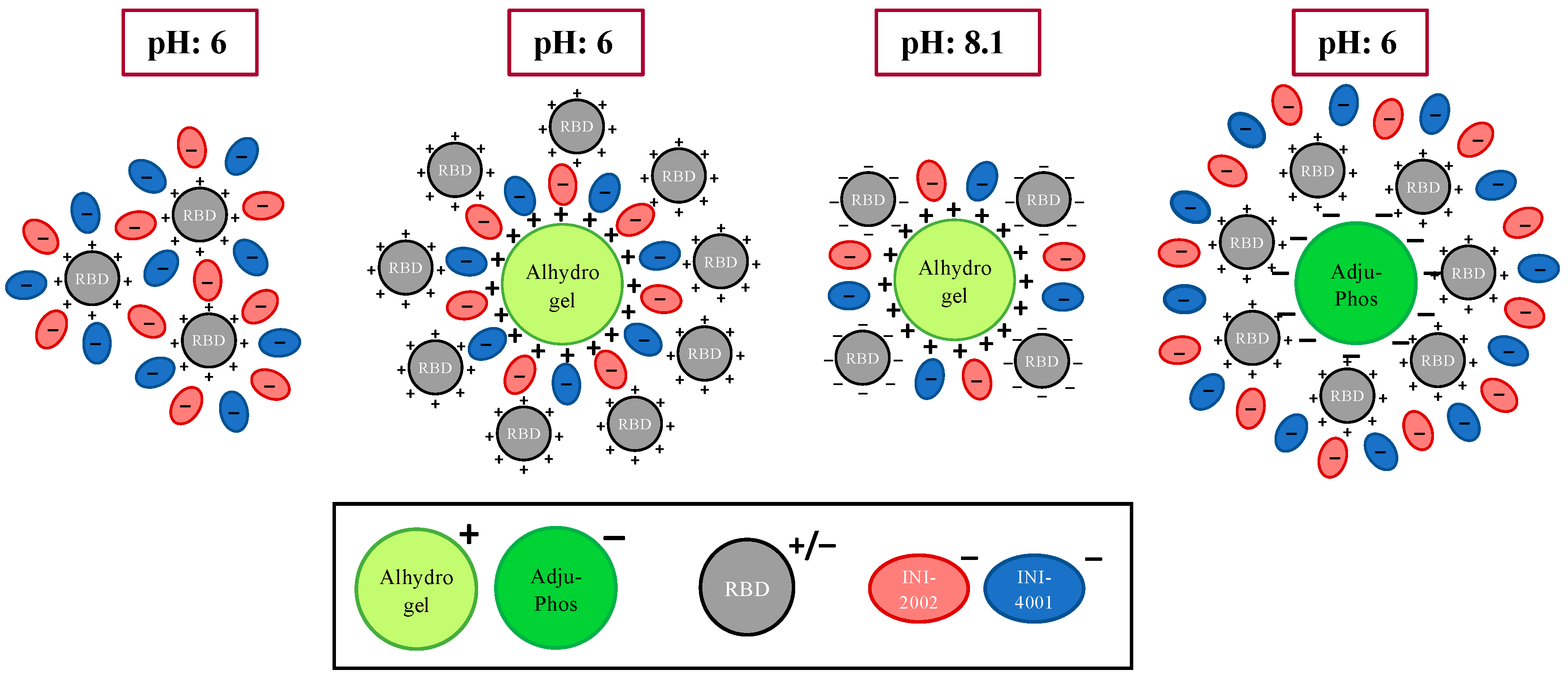

Figure 2 indicated efficient adsorption in 2% glycerin or TRIS buffer. The results also demonstrate that neither TLR ligand desorbed when used in combination, nor in the presence of RBD. Adjuvants and antigens adsorb to AH either by ligand exchange, electrostatic attraction, or hydrophobic forces. As shown in

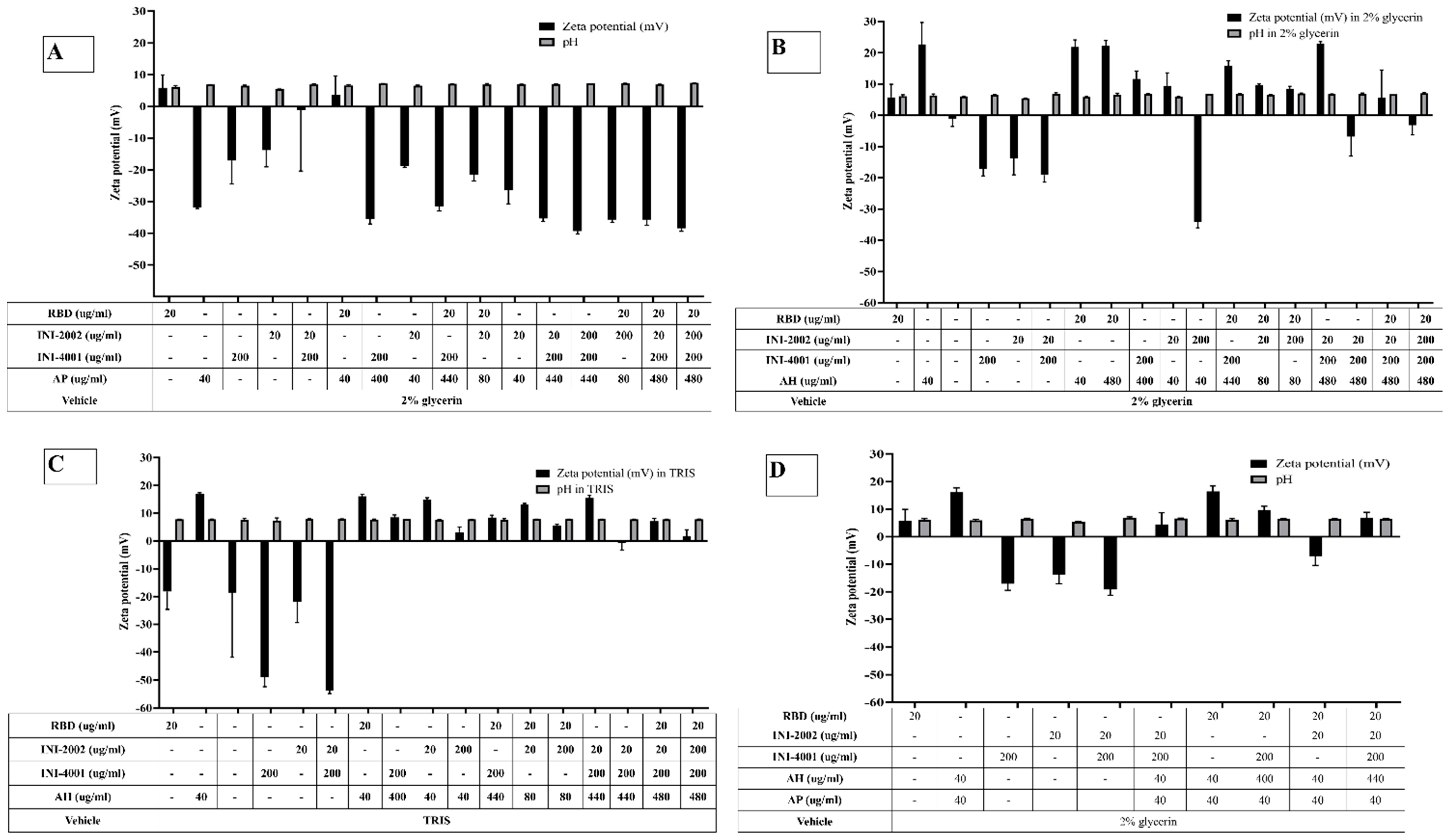

Figure 1, INI-4001 and INI-2002 have phosphate and sulfate groups, respectively, in their structures that could facilitate ligand exchange with the hydroxyl groups of AH to promote adsorption. The zeta potential values (

Figure 3) of INI-4001 and INI-2002 in 2% glycerin and TRIS buffer are negative, whereas the zeta potential of AH in 2% glycerin and TRIS buffer is positive. After mixing of INI-4001 to AH, the zeta potential of AH was reduced from 25 mV to 11.6 ± 2.6 (2% glycerin) and 6.8 ± 0.1 mV (TRIS), indicative of adsorption. Similarly, the mixing of INI-2002 to AH decreased the zeta potential of AH to 9.4 ± 4.1 (in 2% glycerin) and 5.9 ± 0.1 mV (in TRIS buffer). Therefore, adsorption may also occur by electrostatic attraction.

The adsorption results for RBD to AH in

Figure 2A indicated that only 6% of RBD adsorbed to AH at a weight ratio of 1:2 when 2% glycerin (pH 6) was used as the formulation vehicle. The adsorption efficiency of RBD to AH didn’t increase even when using 24 times the amount of AH. This suggests that RBD doesn’t adsorb to AH. However, the adsorption efficiency of RBD to AH at 1:2 significantly improved to 80% (p value= 0.0002) when TRIS buffer at pH 8.1 was used as the formulation vehicle. The isoelectric point of RBD is 7.78, indicating RBD is positively charged at a pH lower than 7.78 and negatively charged at a pH above 7.78. When 2% glycerin was used as the formulation vehicle, the zeta potential of RBD and AH was +5.7 mV (pH 6.09) and +22.68 mV (pH 6.36), respectively (

Figure 3B). The zeta potential of AH didn’t change after mixing with RBD, which corroborates the fact that the neutrally charged RBD doesn’t adsorb to the positively charged AH. When TRIS buffer at pH 8.1 was used as the formulation vehicle, the zeta potential of RBD flipped to a negative charge (-18.20 mV at pH 7.8), which facilitated its adsorption to positively charged AH by electrostatic attraction (

Figure 3C). Hence, switching the formulation vehicle from 2% glycerin to TRIS buffer greatly increased the adsorption efficiency. This approach of modulating the formulation pH in order to flip the charge of the antigen and thereby enhance its adsorption can be used for cationic antigens that don’t otherwise adsorb to AH.

Alternately, RBD efficiently adsorbed to AH without TRIS buffer when the AH was pre-adsorbed to INI-4001 and/or INI-2002, improving from 6.5% to more than 65% (

Figure 2A). With the addition of RBD, the zeta potential of the AH formulation with INI-4001 changed from +11 mV to +15 mV (

Figure 3B), suggestive of adsorption of RBD to AH. The adsorption of anionic ligands on the surface of the cationic AH could provide negatively charged areas to facilitate the subsequent adsorption of RBD. Thus, the combination of INI-4001 and/or INI-2002 along with RBD can be adsorbed in the correct order of addition and co-delivered with AH, even at pH 6.

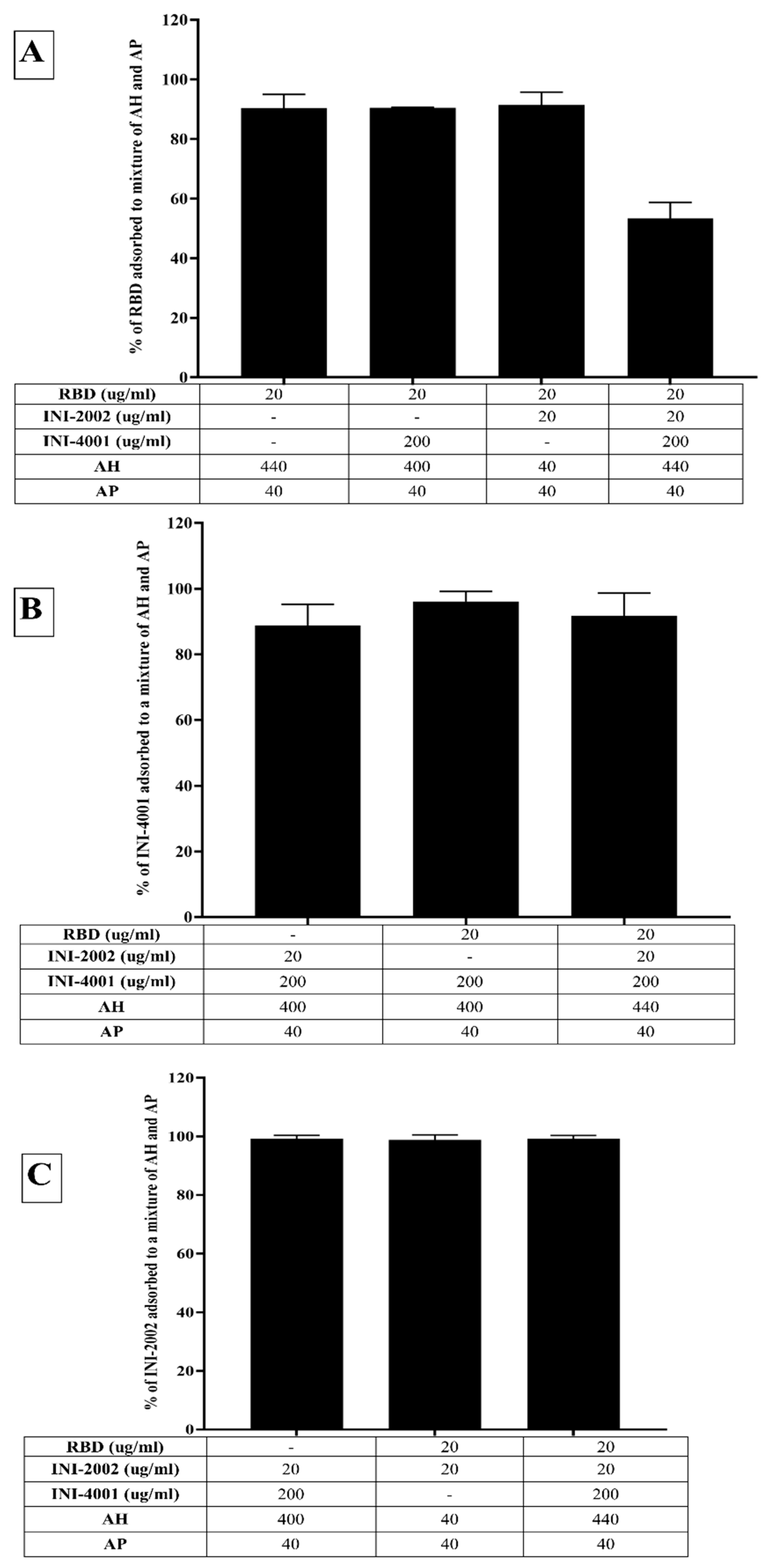

3.3. Adsorption characteristics of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to AP

Although we could achieve efficient adsorption of TLR ligands and RBD to AH, we also evaluated the adsorption of TLR ligands and RBD to AP as a potential alternative. INI-4001 and INI-2002 both adsorbed poorly to AP (

Figure 4B-C), with an adsorption efficiency of approximately 20%. Unlike AH, AP does not possess the hydroxyl groups necessary for ligand exchange with the functional groups in an adjuvant. Additionally, the aqueous formulations of INI-4001 and INI-2002 are negatively charged (-31mV at pH 6.9), making it more challenging for the TLR ligands to adsorb to negatively charged AP.

On the other hand, RBD adsorbed efficiently to the negatively charged AP in 2% glycerin with an adsorption efficiency of 87% (

Figure 4A). After mixing with RBD, the zeta potential of AP changed from -31 mV (pH 6.9) to + 3 mV (pH 6.6) (

Figure 3A), indicative of the adsorption of RBD to the negatively charged AP. Interestingly, the adsorption of RBD on AP promoted the subsequent adsorption of the TLR ligands. As observed in

Figure 4B,C, INI-4001 and INI-2002 adsorbed poorly to AP in the absence of RBD, but their adsorption efficiency increased with the inclusion of RBD. These results suggested an enhancement in the adsorption of the TLR ligands to AP in the presence of RDB. Thus, both the TLR ligands (INI-4001 and INI-2002) and RBD can be adsorbed and co-delivered using AP, albeit to a lower level than the optimized AH formulation.

3.4. Adsorption characteristics of INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD to a mixture of AH and AP

In light of the fact that the TLR ligands and RBD efficiently adsorbed to AH and AP, respectively, we also developed a formulation containing both the TLR ligands pre-adsorbed to AH (INI-4001 and INI-2002) and RBD pre-adsorbed to AP. Consistent with the previous results, RBD and the TLR ligands adsorbed well to AH and AP, respectively (

Figure 5A). Upon mixing, the TLR ligands didn’t desorb (

Figure 5B), but the addition of all the components lowered the adsorption efficiency of RBD from 90% to 53%, indicating the desorption of RBD from AP. The zeta potential of the formulation composed of only AH and AP was +16.17 mV (pH 5.95), while that of the formulation comprising AP, AH, and TLR agonists was +4.47 mV (pH 6.6). This reduction indicates adsorption of the TLR agonists to AH. The addition of RBD to the formulation of AP, AH, and TLR agonists increased the zeta potential to 6.87 (pH 6.53), reflecting the partial adsorption of RBD in the formulation.

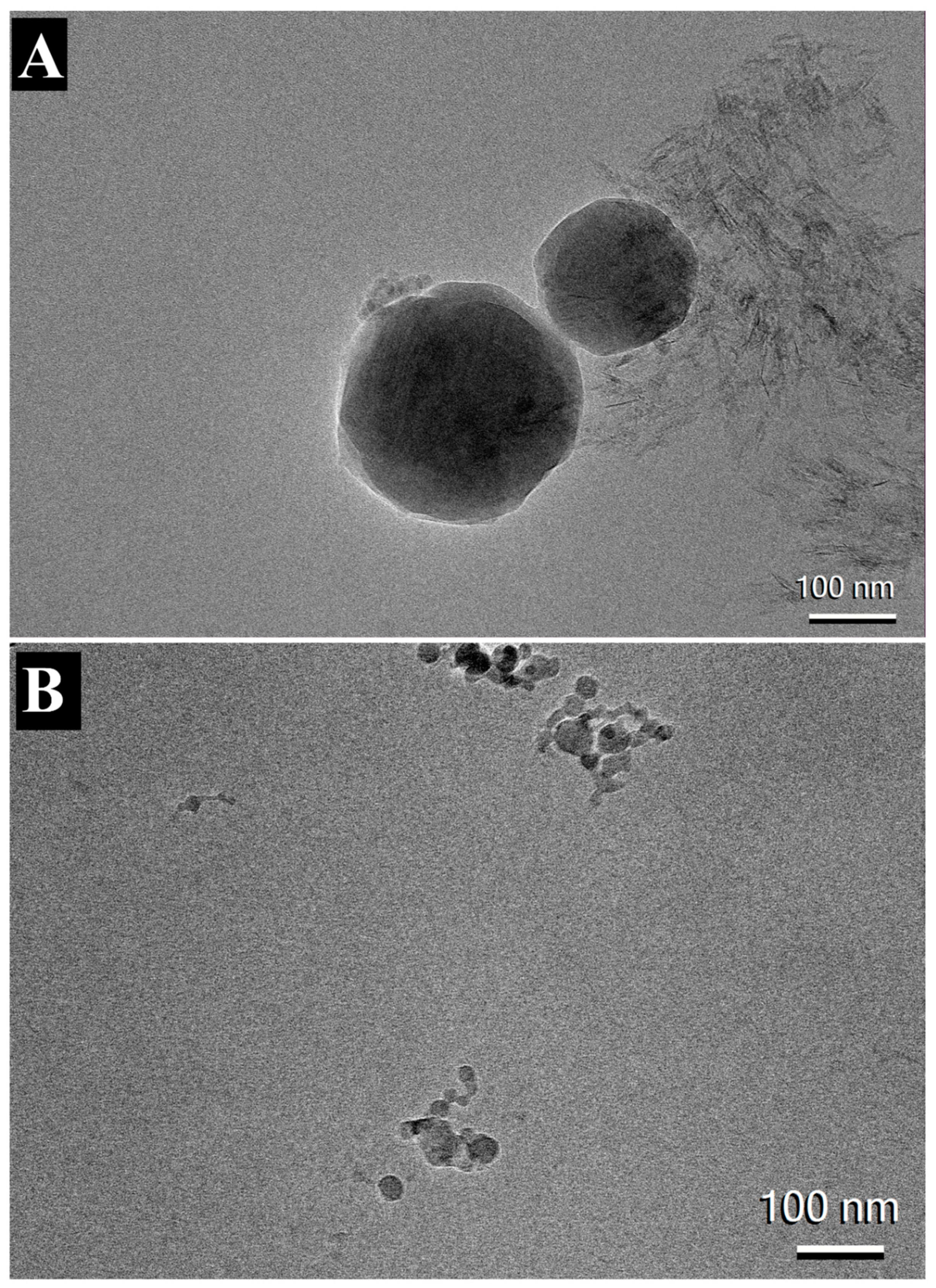

3.5. Visualization of AH and AF formulations

The morphology of AH and AP formulations adsorbed with INI-4001, INI-2002 and RBD were visualized using cryo-TEM microscopy. Consistent with previously published results, both the formulations appeared to have particles with dimensions around 100nm [

33,

39,

40]. The images of AH formulation adsorbed with TLR agonists and RBD showed long and crystalline AH particles adsorbed with nanoparticles of TLR ligands (

Figure 6A). In contrast, AP particles in

Figure 6B appeared to have amorphous quasi-shaped structures.

3.6. In vivo evaluations of alum adsorbed formulations

To determine the impact of adsorption and co-delivery of TLR ligands and RBD to aluminum salts on vaccine-mediated immunity, we vaccinated C57BL/6 mice with different combinations of TLR ligands and RBD adsorbed to AH and AP. Mice were dosed with 1µg RBD, with 10µg INI-4001, and/or 1/ 10µg INI-2002. The amount of aluminum salt (AH or AP) used for dosing was 2 times the mass of antigen and adjuvant (INI-4001 or INI-2002) in each formulation.

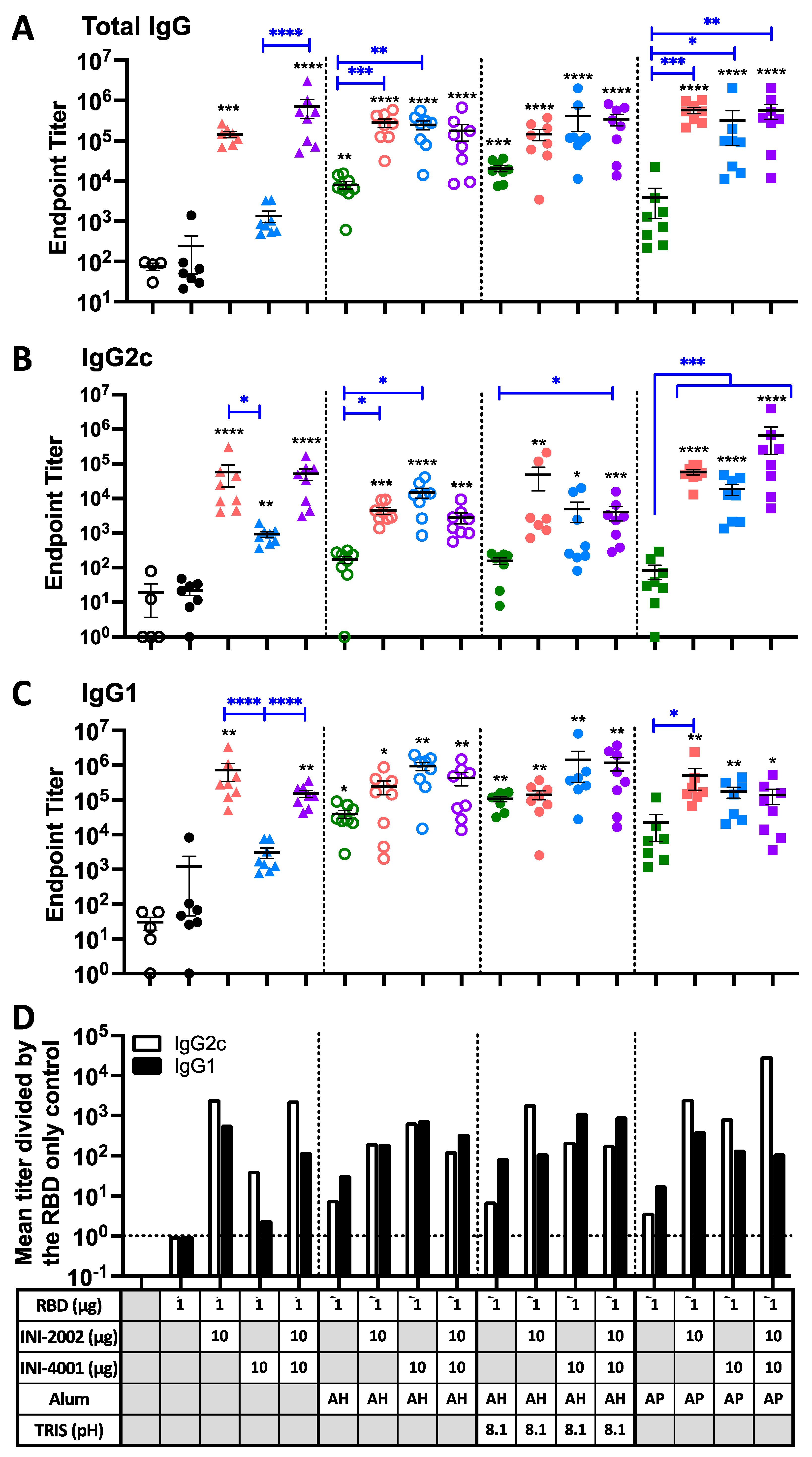

3.7. The addition of TLR ligands to alum-adjuvanted RBD enhances the antibody response

Mice were vaccinated twice, 14 days apart, with 1 µg of purified, recombinant spike RBD with or without the indicated adjuvants. Serum was collected 14 days after the second vaccination and anti-RBD antibody titers were measured by ELISA. As shown in

Figure 7A, left side, animals that received RBD antigen alone (filled black circles) exhibited very low RBD-specific antibodies titers, similar to control mice injected with vehicle alone (open black circles). In the absence of alum, the addition of the TLR4 ligand INI-2002 (red) significantly increased RBD-specific IgG titers, while the TLR7/8 ligand INI-4001 (blue) gave only a modest boost (not statistically significant). However, when the two TLR agonists were combined, an even greater increase in anti-RBD titer was measured (purple triangles, p<0.0001). Significant increases were noted in both IgG2c (

Figure 7B) and IgG1 (

Figure 7C), but the IgG2c levels were preferentially increased, suggestive of a Th1-dominated response (

Figure 7D). As both TLR agonists are negatively charged, it is possible that their interaction with the positively-charged RBD antigen facilitates co-delivery to antigen-presenting cells in order to promote the vaccine-induced immune response.

Adjuvanting RBD with AH (either at pH 6 or 8.1) or AP resulted in modestly increased titers (green symbols). No significant difference in antibody titers between AH at pH 6 or 8.1 was seen, although a trend towards higher titers was seen at pH 8.1 (the TRIS formulation with higher RBD adsorption). The addition of a TLR ligand significantly enhanced the anti-RBD titers beyond the level seen with either alum formulation alone, especially with the TLR7/8 ligand INI-4001 (blue). As might be expected in the presence of alum, the relative increase in IgG1 was slightly higher than IgG2c for most formulations containing AH (

Figure 7D). However, the AP-containing formulations did not follow this trend, as the TLR ligands preferentially increased levels of IgG2c. For vaccines containing both TLR ligands in combination, the presence of alum did not significantly augment the response above the level in the absence of alum (compare purple symbols).

We hypothesize that the negatively-charged TLR agonists would directly interact with the positively-charged RBD antigen. In this situation, the TLR4 ligand INI-2002 will be surface accessible and capable of engaging TLR4 receptors on antigen-presenting cells to promote the desired immune response (

Figure 8, left). However, in the absence of the TLR4 ligand, the TLR7/8 agonist does not enhance immunogenicity as well, perhaps because cellular uptake is first required to engage the receptors. This is overcome by the addition of alum, which causes the formation of larger particles that likely promote uptake by antigen-presenting cells, allowing the INI-4001 to engage its intracellular receptor.

Groups containing alum as the only adjuvant exhibited a greater increase in RBD-specific IgG1 vs IgG2c, consistent with the expected Th2 response from alum adjuvants. Adding TLR agonists resulted in a greater IgG2c increase, suggesting these TLR ligands bias the immune response away from the Th2-dominated phenotype. However, having both alum and TLR ligands enhances both isotypes, suggesting it develops a more balanced immune response.

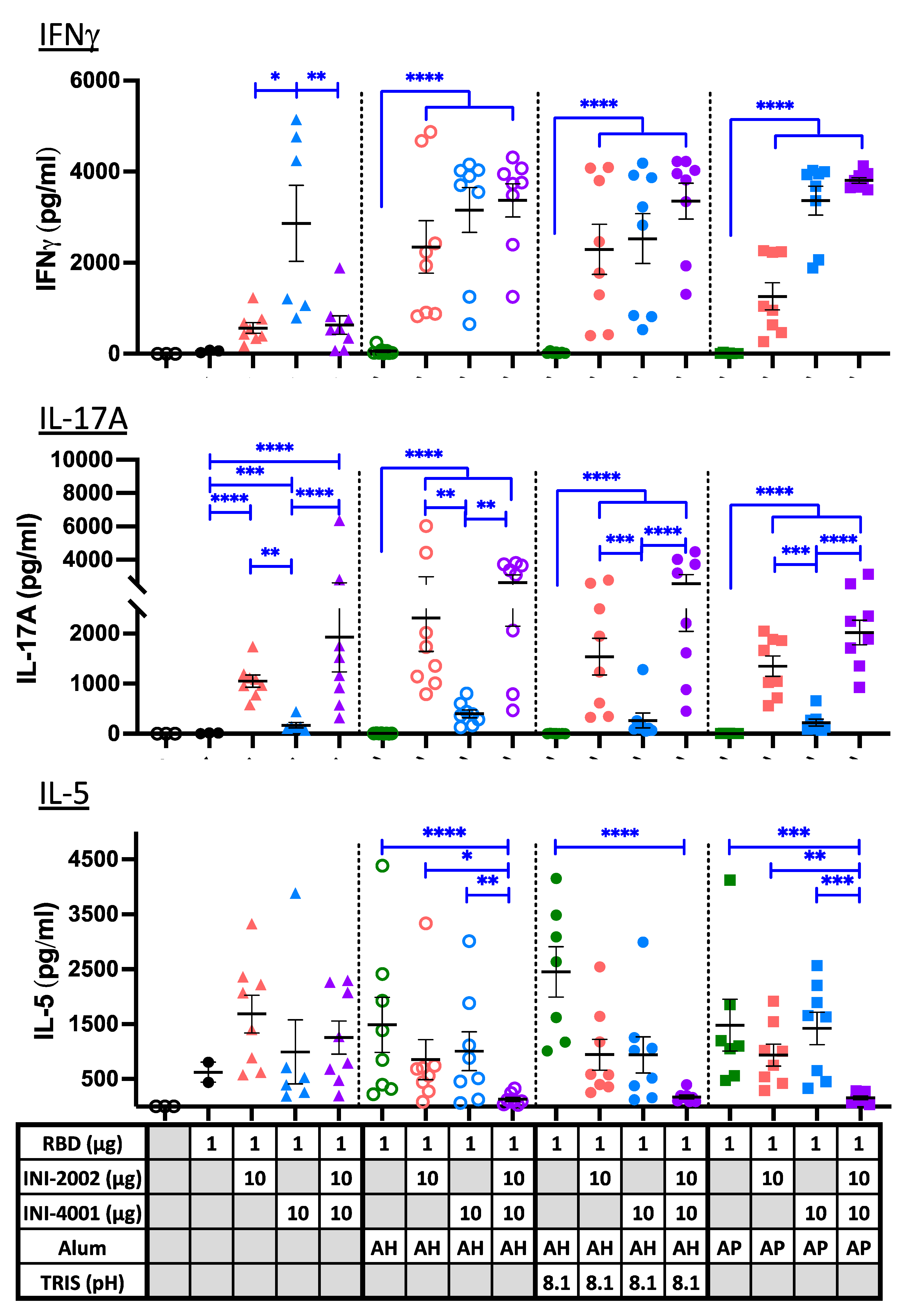

3.8. Cell-mediated immunity to RBD is modulated by alum and TLR ligands.

Antibody isotype titers give an indication of the type of CD4

+ T helper response that has developed, but we further explored this using a more direct measure of the antigen-specific T cell phenotype that developed in secondary lymphoid tissues following vaccination. Single-cell suspensions isolated from the draining lymph nodes (dLN) and spleens of animals five days after a 3

rd vaccination were cultured with RBD for approximately 72 hours to restimulate existing antigen-specific T cells. Cytokines released into the cell supernatant during this restimulation were measured with a multiplex ELISA (

Figure 9). IFNγ is a signature cytokine released by Th1 T cells and was used as an indication of Th1 development. IL-17A is released by Th17 cells, and IL-5 is a signature cytokine secreted by Th2 cells (along with IL-4 and IL-13, not measured). In the absence of alum (triangles), the TLR7/8 ligand INI-4001 induced a Th1-biased response, with high IFNγ production and very little IL-17A or IL-5. The TLR4 ligand INI-2002 drove the development of Th17 cells along with somewhat lower levels of Th1 and Th2, resulting in a mixed T helper cell response. The combination of the two ligands resulted in a response similar to that of INI-2002 alone, suggesting that INI-2002 dominates the response in the absence of alum.

The alum-containing formulations in the absence of TLR ligands (green symbols) failed to elicit IFNγ- or IL-17A-producing T cells, resulting a Th2-dominated immune response (evidenced by IL-5 production), as expected. The addition of TLR7/8 ligand INI-4001, either alone (blue) or in combination with INI-2002 (purple), resulted in an enhanced development of IFNγ-producing Th1 cells above what was seen in the absence of alum. Again, the TLR4 ligand INI-2002 promoted the additional development of IL-17A-producing (Th17) cells, even in the presence of alum. A moderate level of IL-5 was also produced by most of the groups, resulting in a mixed T cell phenotype that corroborates the mix of antibody isotypes that were previously noted. The exception to this occurred when both TLR ligands were added to alum, which abrogated nearly all IL-5-producing cells while promoting the development of Th1 and Th17 cells instead.

To summarize these results, the addition of TLR ligands to alum results in an additive mix of what is seen from each independently; Th2 cells develop due to alum, and Th1 and/or Th17 cells develop due to the TLR ligands. However, mixing the two ligands appears to overcome the alum-induced Th2 development, perhaps due to the increased development of Th1 and Th17 cells. When alum was not included in the vaccines (triangles), the overall level of antigen-specific T cell cytokines was lower, suggesting that alum enhances antigen-specific T cell development without notably skewing the response. The enhanced antibody response with the use of alum (most noticeable in formulations with INI-4001) along with an enhancement of Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T cell responses should offer enhanced protection against viral infection over what each of these adjuvants would promote on their own.

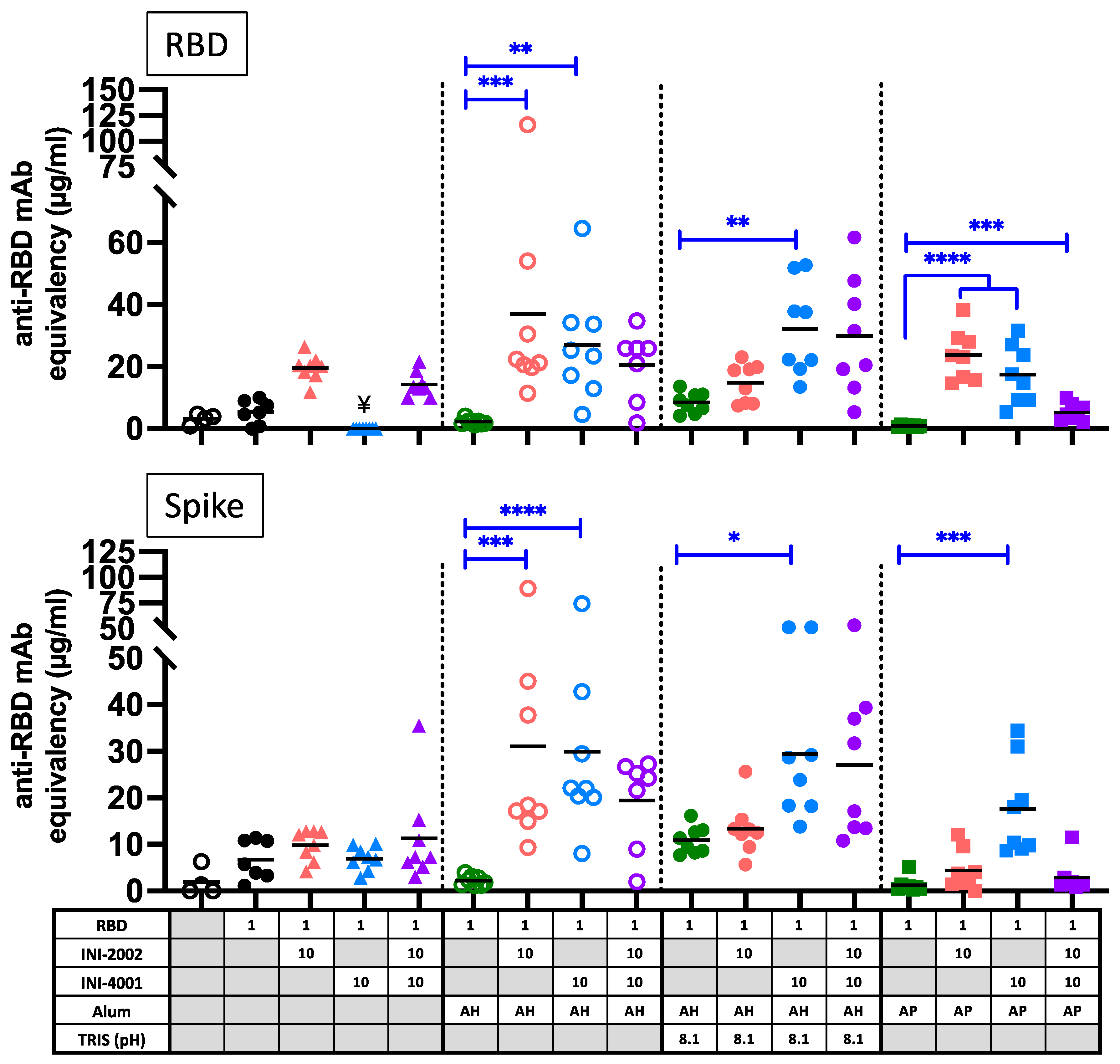

3.9. Improved neutralizing antibodies with the combination of alum and TLR ligands.

An important correlate of protection in COVID-19 infection is the presence of neutralizing antibody titers. Therefore, the serum collected 14 days after booster vaccination was tested for the ability to prevent the binding of RBD or spike (S) glycoprotein to hACE2 protein, as an indication of virus neutralizing potential (

Figure 10). The addition of either TLR agonist to the alum formulations enhanced the production of antibodies that block the binding of RBD or spike to hACE2. Overall, the neutralization potential correlated with the level of RBD-specific IgG antibody titers (compare to

Figure 7), with a few notable exceptions. Serum antibodies from mice vaccinated with AP containing both TLR agonists (purple squares) had notably lower neutralizing potential than would be expected based on the anti-RBD antibody titers. Also striking is the lack of neutralization potential of serum after vaccination with INI-2002 or the combination of INI-2002 and INI-4001 in the absence of alum (triangles). While these vaccines resulted in high anti-RBD antibody titers, these sera were less effective at preventing the binding of RBD or Spike to hACE2. Therefore, the presence of aluminum salt improved the quality of antigen-specific antibodies, while the addition of TLR agonists both enhanced these titers and encouraged the development of a strong Th1 cell-mediated response.

Figure 1.

Structures of INI-4001 (A) and INI-2002 (B).

Figure 1.

Structures of INI-4001 (A) and INI-2002 (B).

Figure 2.

Adsorption efficiencies of (A) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to AH.

Figure 2.

Adsorption efficiencies of (A) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to AH.

Figure 3.

Zeta potential and pH of mixtures of RBD, INI-4001 and INI-2002 with (A) AP (B) AH in 2% glycerin as formulation vehicle (C) AH in TRIS buffer as the formulation vehicle, and (D) Combination of AH and AP.

Figure 3.

Zeta potential and pH of mixtures of RBD, INI-4001 and INI-2002 with (A) AP (B) AH in 2% glycerin as formulation vehicle (C) AH in TRIS buffer as the formulation vehicle, and (D) Combination of AH and AP.

Figure 4.

Adsorption efficiencies of (A) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to AP. The results suggest that RBD adsorbed to AP and facilitated adsorption of INI-4001 and INI-2002.

Figure 4.

Adsorption efficiencies of (A) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to AP. The results suggest that RBD adsorbed to AP and facilitated adsorption of INI-4001 and INI-2002.

Figure 5.

Adsorption efficiencies of (B) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to a mixture of AH and AP.

Figure 5.

Adsorption efficiencies of (B) RBD, (B) INI-4001 and (C) INI-2002 to a mixture of AH and AP.

Figure 6.

CryoTEM image of AH (a) and AP (b) adsorbed with RBD, INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD.

Figure 6.

CryoTEM image of AH (a) and AP (b) adsorbed with RBD, INI-4001, INI-2002, and RBD.

Figure 7.

RBD-specific serum IgG antibody titers. Titer of RBD-binding antibodies in serum from 14 days after booster A) IgGB IgG2c isotype (C) IgG1 isotype. D) relative fold-change in the mean titer of RBD-specific IgG2c (open) or IgG1 (filled) over the mean titer of the RBD alone group. Black lines indicate the mean and standard error of the mean for each group, while individual mice are represented by symbols. Black asterisks designate significant differences compared to the RBD antigen-only group (solid black circles). Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation. *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Figure 7.

RBD-specific serum IgG antibody titers. Titer of RBD-binding antibodies in serum from 14 days after booster A) IgGB IgG2c isotype (C) IgG1 isotype. D) relative fold-change in the mean titer of RBD-specific IgG2c (open) or IgG1 (filled) over the mean titer of the RBD alone group. Black lines indicate the mean and standard error of the mean for each group, while individual mice are represented by symbols. Black asterisks designate significant differences compared to the RBD antigen-only group (solid black circles). Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation. *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the interactions of RBD, INI-4001, and INI-2002 with AH and or AP.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the interactions of RBD, INI-4001, and INI-2002 with AH and or AP.

Figure 9.

Cytokine release from RBD-specific T cells upon restimulation. Cytokine concentrations in supernatants recovered from a 72 hour culture of ex vivo dLN cell suspensions stimulated with 10µg/ml RBD protein. Cells were recovered and cultured five days after a third vaccination to assess the phenotype of RBD-specific T cells. Black lines indicate the mean and standard error of the mean for each group, while individual mice are represented by symbols. Black asterisks designate significant differences compared to the RBD antigen only group (solid black circles). Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation (aqueous or alum type) *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Figure 9.

Cytokine release from RBD-specific T cells upon restimulation. Cytokine concentrations in supernatants recovered from a 72 hour culture of ex vivo dLN cell suspensions stimulated with 10µg/ml RBD protein. Cells were recovered and cultured five days after a third vaccination to assess the phenotype of RBD-specific T cells. Black lines indicate the mean and standard error of the mean for each group, while individual mice are represented by symbols. Black asterisks designate significant differences compared to the RBD antigen only group (solid black circles). Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation (aqueous or alum type) *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Figure 10.

Surrogate neutralization assay with serum antibodies from 14 days after booster vaccination. The ability to block the interaction between human ACE2 and RBD (top) or trimerized spike ectodomain (bottom) was assessed by a competitive ELISA-based assay. Black lines indicate the mean of the group, and symbols represent data from individual animals. Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation (aqueous or alum type). ¥ indicates samples that were below detection in this assay. *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Figure 10.

Surrogate neutralization assay with serum antibodies from 14 days after booster vaccination. The ability to block the interaction between human ACE2 and RBD (top) or trimerized spike ectodomain (bottom) was assessed by a competitive ELISA-based assay. Black lines indicate the mean of the group, and symbols represent data from individual animals. Blue lines and asterisks specify significant differences among groups receiving the same type of formulation (aqueous or alum type). ¥ indicates samples that were below detection in this assay. *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001, ****=p<0.0001.

Table 1.

Formulation composition of the various SARS-CoV-2 sub-unit vaccines containing RBD and TLR ligands.

Table 1.

Formulation composition of the various SARS-CoV-2 sub-unit vaccines containing RBD and TLR ligands.