1. Introduction

The threat of a nuclear or radiological event is a serious concern for all government agencies involved in public health preparedness and national security as well as for the military personnel [

1,

2]. Management of such nuclear and radiological causalities as a result of nuclear power plant accidents or safety failures, natural calamities, terrorist attacks or military conflicts will need medical interventions [

3,

4,

5]. The BioShield legislation signed into law on July 21, 2004 provides new tools to improve preparedness for Americans against a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) threat [

6,

7,

8]. In the event of a nuclear or radiological scenario, medical care would be needed to treat radiation-exposed victims developing acute radiation syndrome (ARS) [

9,

10,

11]. Acute radiation injury occurs at total-body doses above 1 Gy, with symptoms growing in severity as the level of radiation exposure increases [

9]. A dose up to 6 Gy for human is characterized by the loss of hematopoietic cell regenerative ability, resulting in hematopoietic ARS (H-ARS).

Biomarkers are important for assessing the dose of radiation exposure as well as for the development of radiation medical countermeasures (MCMs). Ionizing radiation is known to induce a cascade of changes that can have serious deleterious implications for key metabolic processes and such metabolomic changes can be used as radiation injury biomarkers [

12,

13,

14]. Metabolomics is an emerging discipline and metabolites are products of biological cascades of proteomic and genomic processes, and the presence of such metabolites is linked with the individual’s tissue/cell phenotype, making them ideal biomarkers for injury or disease progression. These metabolite biomarkers are also useful due to their comparative ease of identification and validation in biological fluids collected without major invasive procedures. Both untargeted (global) as well as targeted (quantitative phase) metabolomic techniques have been widely used in various settings of radiation injuries [

13,

14]. Sometimes the appearance of H-ARS as a differential diagnosis is detected late and not until the preterminal stage as in the Litvinenko case with radionuclide incorporation [

15,

16,

17]. Similar was the situation in the large-scale exposure event of Goiania, Brazil, which occurred due to a misused orphan radioactive source [

18,

19]. Thus, the identification of biomarkers for preterminal stage is important.

Nonhuman primates (NHPs) are the gold standard of animal models acceptable to the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) for advanced development of biomarkers and countermeasures to evaluate translational feasibility for humans [

20]. Although a large number of studies have been performed that assessed concentrations of metabolic profiles in blood plasma/serum and tissue samples collected from NHPs exposed to various types and doses of radiation [

13,

14], no study has investigated the metabolic profiles in samples collected from radiation-exposed moribund (preterminal) NHPs. There is interest to know whether changes in biofluids can serve as biomarkers for prefinal deteriorated health status [

21]. In order to understand this, we studied the altered metabolites in peripheral blood plasma samples collected from moribund NHPs that did not survive after lethal radiation exposure. In brief, the purpose of this study was to characterize the metabolomic changes in blood plasma collected from NHPs following exposure to 7.2 Gy (LD

70/60) total-body ionizing radiation with particular attention on how the metabolite profiles differed from those samples collected at pre-exposure and early post-exposure timepoints. In our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the metabolic profiles in irradiated samples collected from moribund (preterminal) NHPs to identify the metabolites significantly altered just before death. The preterminal samples were collected immediately prior to euthanasia of moribund animals, which ultimately provide insight into the preterminal phenotype of moribund animals. This data is of particular interest because it allows for the identification of potential patterns in dysregulated metabolites that may be used as biomarkers during triage after a mass casualty scenario.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

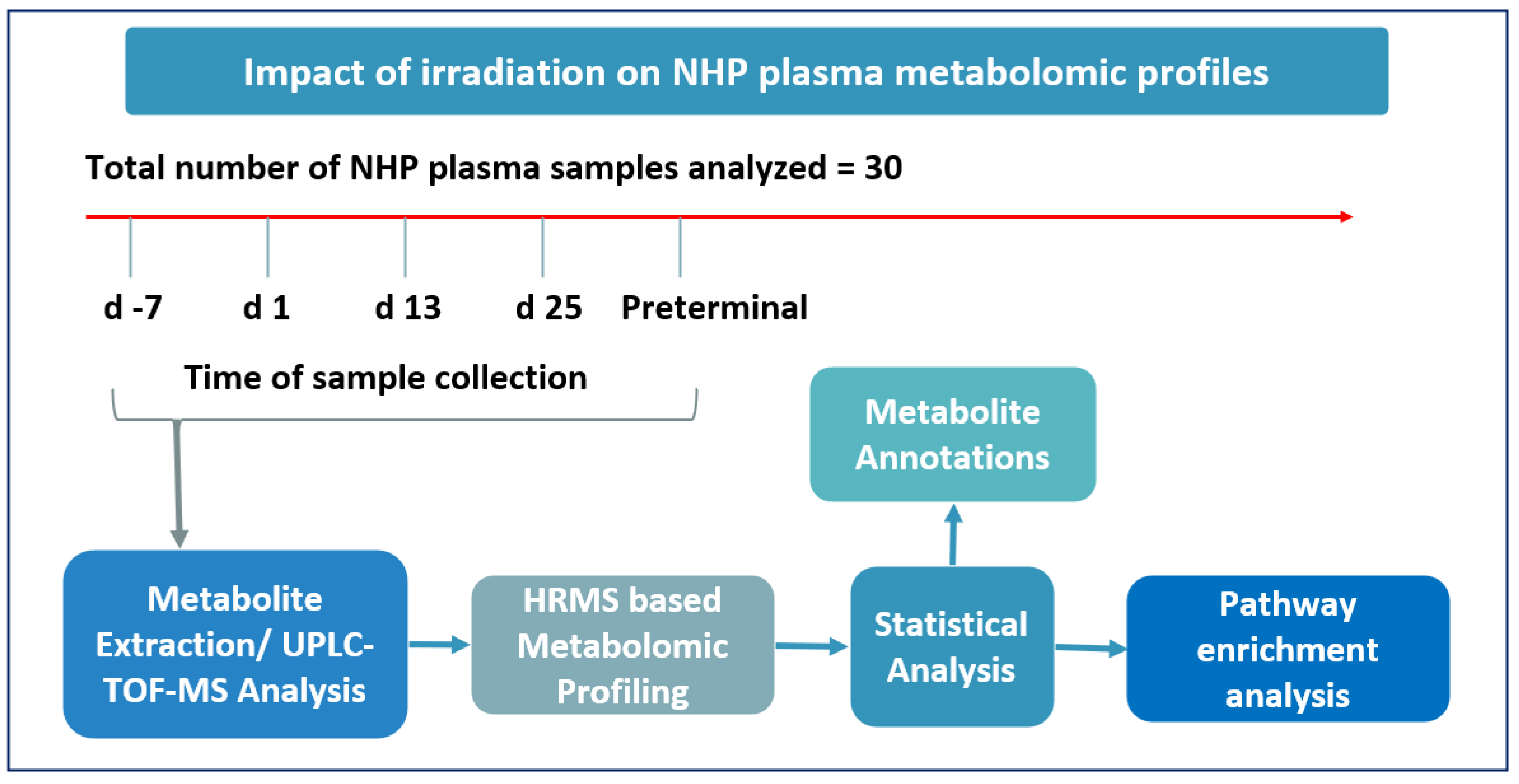

The primary objective of this study was to identify metabolic changes in plasma samples collected from NHPs prior to and following exposure to 7.2 Gy TBI as well as in samples collected from preterminal animals. Preterminal samples have been compared with samples from animals prior to irradiation and at several timepoints after irradiation. Details of the experimental design can be viewed in

Figure 1.

2.2. Animals

Fourteen male NHPs (

Macaca mulatta, Chinese sub-strain) between the ages of 3.0 to 5.3 years and weighing 3.89 to 6.34 kg were procured from the National Institutes of Health Animal Center located in Poolesville, MD. These animals were housed at the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI) vivarium, a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-International. Prior to initiation of the study, the animals underwent a mandatory quarantine for seven weeks. Animals were housed individually to prevent possible conflict injuries; however, cage dividers were present which allowed for animals to interact socially. A primate diet (Teklad T.2050 diet; Harlan Laboratories Inc., Madison, WI, USA) was provided twice per day, with at least 6 h between feedings (each animal was provided 4 biscuits at 7:00 AM and 2:00 PM). Drinking water was provided

ad libitum. The study design and animal procedures were reviewed and approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Department of Defense Animal Care and Use Review Office (ACURO). All animal procedures strictly adhered to the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals throughout this study as described earlier [

22,

23].

2.3. Irradiation

Animals were grouped in pairs for radiation exposure; pairing was based on comparability of their abdominal lateral separation measurements (+/- 1 cm). These measurements were taken using a digital caliper at the core of the abdomen. Animals with an abdominal measurement that was not within 1 cm of another animal’s measurements were irradiated individually. Beginning approximately 12 – 18 h prior to radiation exposure, all NHPs were fasted to reduce the risk of radiation-induced vomiting. About 15 minutes prior to irradiation, animals were restrained using the squeeze-back mechanism of their cage, and sedated with 10 – 15 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/ml) administered intramuscularly (

im). The sedated animals were placed in custom-made Plexiglas restraint boxes and secured using ropes that anchored to their arms and legs in place. NHPs were given a booster (0.1 – 0.3 ml

im) of ketamine if needed immediately prior to initiating the radiation exposure to reduce any potential movement. The NHP pair was then placed facing opposite directions on the irradiation platform, and were exposed to cobalt-60 total-body gamma radiation at a dose of 7.2 Gy and a dose rate of 0.6 Gy/min. After radiation exposure, NHPs were returned to their home cages and monitored closely by study staff until they completely recovered from sedation. Additional details of total-body irradiation and dosimetry are given in earlier publications [

24,

25]. Animals were exposed to radiation between 8:00 AM and 12:00 noon.

2.4. Cage-side animal observations

Cage-side animal observations were performed at least twice a day in the morning and the afternoon for the quarantine and study periods. Beginning on the day of irradiation, clinical observations were recorded and reported to the study director and veterinarian once per day. Between days 10 to 20 post-irradiation, animals were observed three times a day between 6 and 8 hours apart. Animals that were deemed moribund using criteria listed on the approved protocol were scheduled for euthanasia based on the veterinarian’s discretion. An on-call veterinary technician/veterinarian was available 24 h a day in the event of an emergency situation [

26].

2.5. Blood sample collection

Plasma fraction was enriched from whole blood samples collected on days -7, 1, 13, and 25, or immediately prior to euthanasia (preterminal). Blood was collected from a peripheral vessel (either saphenous or cephalic vein) as described earlier [

27]. The desired volume of blood was collected with a 3 ml disposable luer-lock syringe with a 25-gauge needle into an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and serum was separated by centrifugation.

2.6. Euthanasia

The study period was for 60 days, however, due to the radiation dose used (7.2 Gy TBI, LD

70/60), a few animals became moribund during the course of study and were deemed candidates for early euthanasia to minimize unnecessary pain and suffering to the animal. Animals were euthanized according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) guidelines as described earlier [

28,

29]. In brief, for euthanasia, animals were sedated with Ketamine hydrochloride (5 – 15 mg/kg,

im) injection, then euthanized by sodium pentobarbital intravenously (>100 mg/kg, Euthasol, Virbac AH, Inc, Fort Worth, TX). Death was confirmed by cessation of pulse, heartbeat, and breathing.

2.7. Sample preparation for LC-MS analysis

For metabolomics analysis, a plasma volume of 25 µl was obtained from each sample and transferred to a newly labeled vial. To each aliquot, a volume of 75 µl of extraction solution (35% water, 25% methanol, 40% isopropanol, 0.001% Debrisoquine, 0.005% 4-nitrobenzoic acid) was added. Samples were then vortexed and incubated for 20 min on ice. A volume of 100 µl of chilled acetonitrile was then added to each sample. Samples were vortexed and kept at -w20 °C for 15 min. Next, samples were centrifuged at 15,500×g at 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant from centrifuged samples was transferred to glass vials. To prevent bias, the sample queue was randomized before data acquisition.

2.8. Plasma metabolomics using UPLC QTOF analysis

Metabolite extraction was performed as described above and described previously [

30]. The sample extracts were resolved on an Acquity UPLC coupled to a Xevo G2 QTOF-MS (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). A volume of 2 μl of each sample was injected onto either an Acquity UPLC BEH C18, 130Å, 1.7 µm, 2.1 mm X 50 mm column maintained at 40 °C for the metabolomics acquisition or a CSH C18, 130Å, 1.7 µm, 2.1 mm X 100 mm column maintained at 65 °C for the lipidomics acquisition. The LC solvents used were 100% water with 0.1% formic acid (A), 100% ACN with 0.1% formic acid (B), 100% isopropanol with 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate (C).

The column eluent was introduced into the QTOF MS that was operating in either positive or negative modes by electrospray ionization [

31]. Accurate mass was maintained by infusing leucine enkephalin (556.2771 m/z) in 50% aqueous acetonitrile (2.0 ng/ml) at a rate of 20 µl/min via the Lockspray interface every 10 seconds. Data was acquired in Centroid mode with a 50.0 to 1200.0 m/z mass range for ToF MS scanning [

25]. The pooled QC was injected every 10 samples to monitor any shifts in retention time and intensities.

2.9. Statistical analysis

In this study, we compared metabolite abundance that is represented by normalized intensity units. Data obtained from electrospray positive and negative modes was analyzed separately. The data matrix had some inherent limitations with respect to sample availability across different time points with some, but not all, having repeat measures. In order to addressing this, we applied both independent (unpaired) and dependent (paired) statistical tests, with results detailed in

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. We considered a p-value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant. For unpaired comparisons, we employed the Mann–Whitney U test, a nonparametric technique, to evaluate the distributional equality between two distinct populations. This test is especially pertinent when the data does not follow normal distribution. For paired comparisons, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized. Both of these tests are appropriate for nonparametric data analysis. To address the issue of multiple comparisons, which heightens the likelihood of false positives, we applied the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method to adjust p-values. This approach is less stringent than traditional family-wise error rate corrections and is more apt for studies with a substantial number of tests. Additionally, our study incorporated the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. This method maps molecules from our dataset onto KEGG's curated biological pathways, providing insight into the biological processes and pathways that are active, altered, or disrupted in our study conditions. KEGG pathway analysis helped contextualize molecular data within a biological framework, offering a comprehensive view of the systemic functions affected by the studied metabolites. Taken together, this approach, combining statistical rigor with biological pathway analysis, ensures a thorough and nuanced interpretation of our findings, considering the variability in sample availability and providing deeper insights into the biological significance of our results.

3. Results

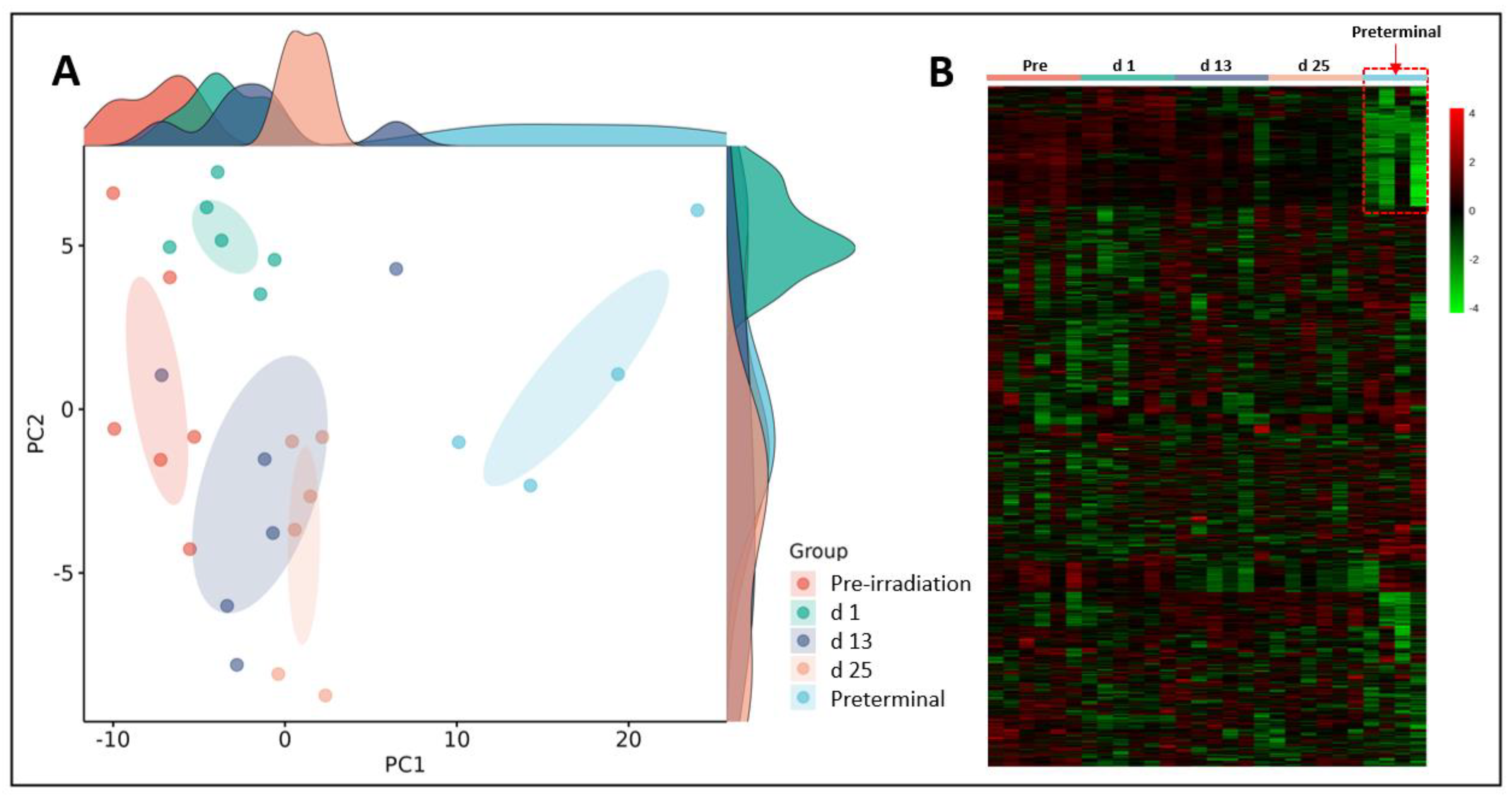

Initially, we performed binary comparisons to assess the effects of radiation on NHP plasma metabolic profiles by comparing samples collected at days 1, 13, or 25 with day -7 (pre-irradiation). Separately, we also compared metabolic profiles of and samples collected at days 1, 13, or 25 with preterminal to assess the metabolic signatures associated with the preterminal state. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) score plot and a heat map were constructed to view overall differences among groups (

Figure 2). The PCA scores for the preterminal samples are distinct from all other scores along the PC1 dimension, which represent the most important directionality within the data matrix. Although dominated by the preterminal scores separation, there is also apparent separation along PC1 of the day 25 scores from a cluster of both the day 13 and day 1 scores, which itself separates to some extent from the pre-irradiation sample scores. Interestingly, we found that along the PC2 dimension, day 1 scores mostly separated from those of day 13 and day 25, suggesting that a noticeable but transient early radiation response in the plasma metabolome is present that warrants further investigation.

3.1. Putative Biochemical Changes Associated with Ionizing Radiation Exposure

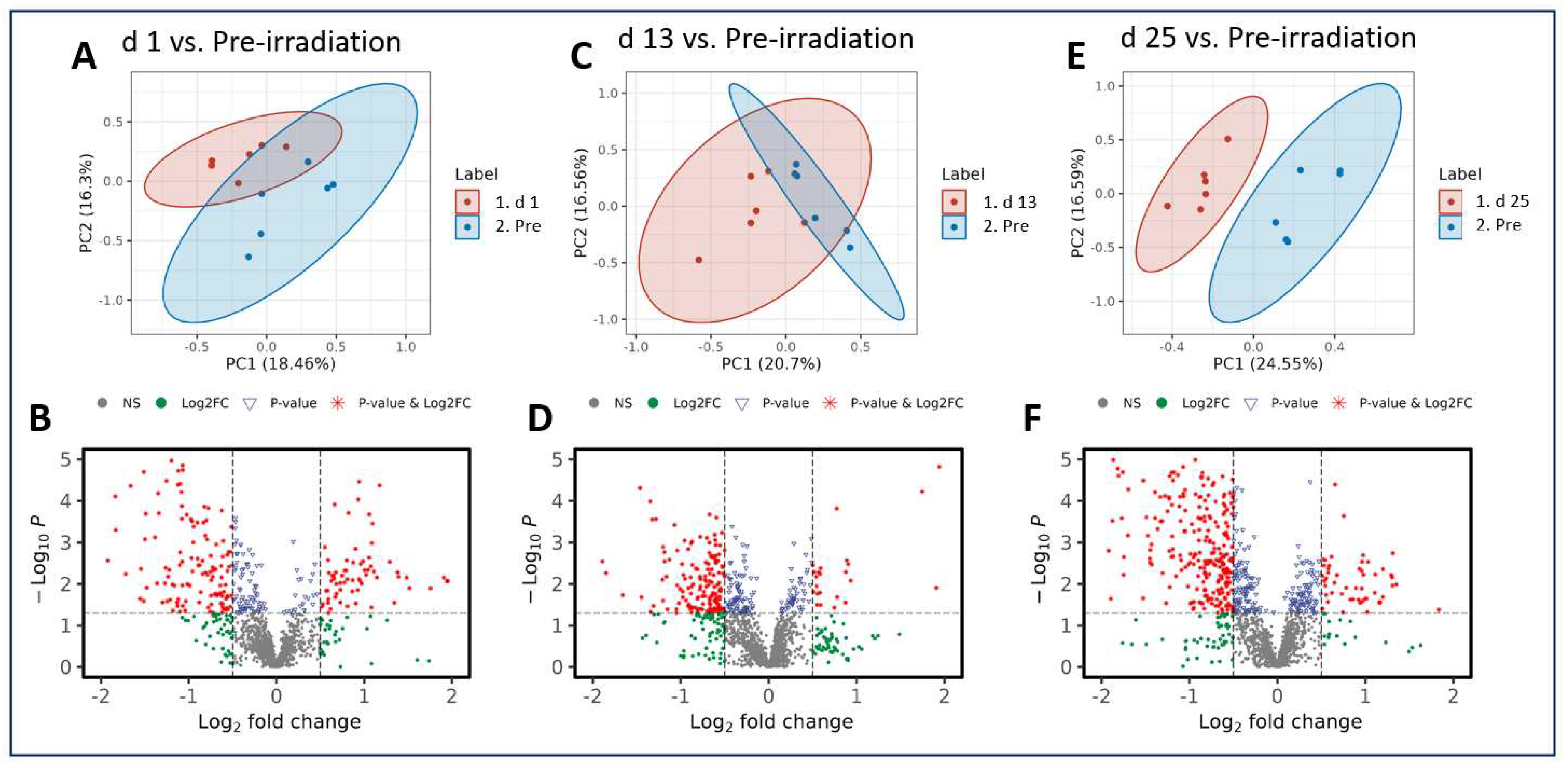

Radiation exposure induced metabolic shifts that were increasingly downregulated as the study progressed. Interestingly, when comparing across all three post-irradiation timepoints (day 1, 13, or 25) to the pre-irradiation timepoint (day -7), the majority of the metabolites analyzed were downregulated, which is demonstrated in the volcano plots (

Figure 3). These included phosphatidylcholine, glycero-3-phosphocholine, and phosphatidylethanolamine (

Table 1). This pairwise stratification of the pre-irradiation timepoint to the post-irradiation timepoints supports the notion that metabolic perturbations following a single IR exposure change substantially over time. The features that were altered significantly in each comparison and that were matched in the Metlin database search are shown as clusters according to their involvements or associations. Prominent among these is the involvement in or association with the alpha-lenolenic acid, choline, and glycerophospholipid metabolic pathways (

Supplementary Figures 1–3, and Supplementary Tables 3 – 5).

3.2. Putative Biochemical Changes Associated with the Preterminal State after Ionizing Radiation Exposure

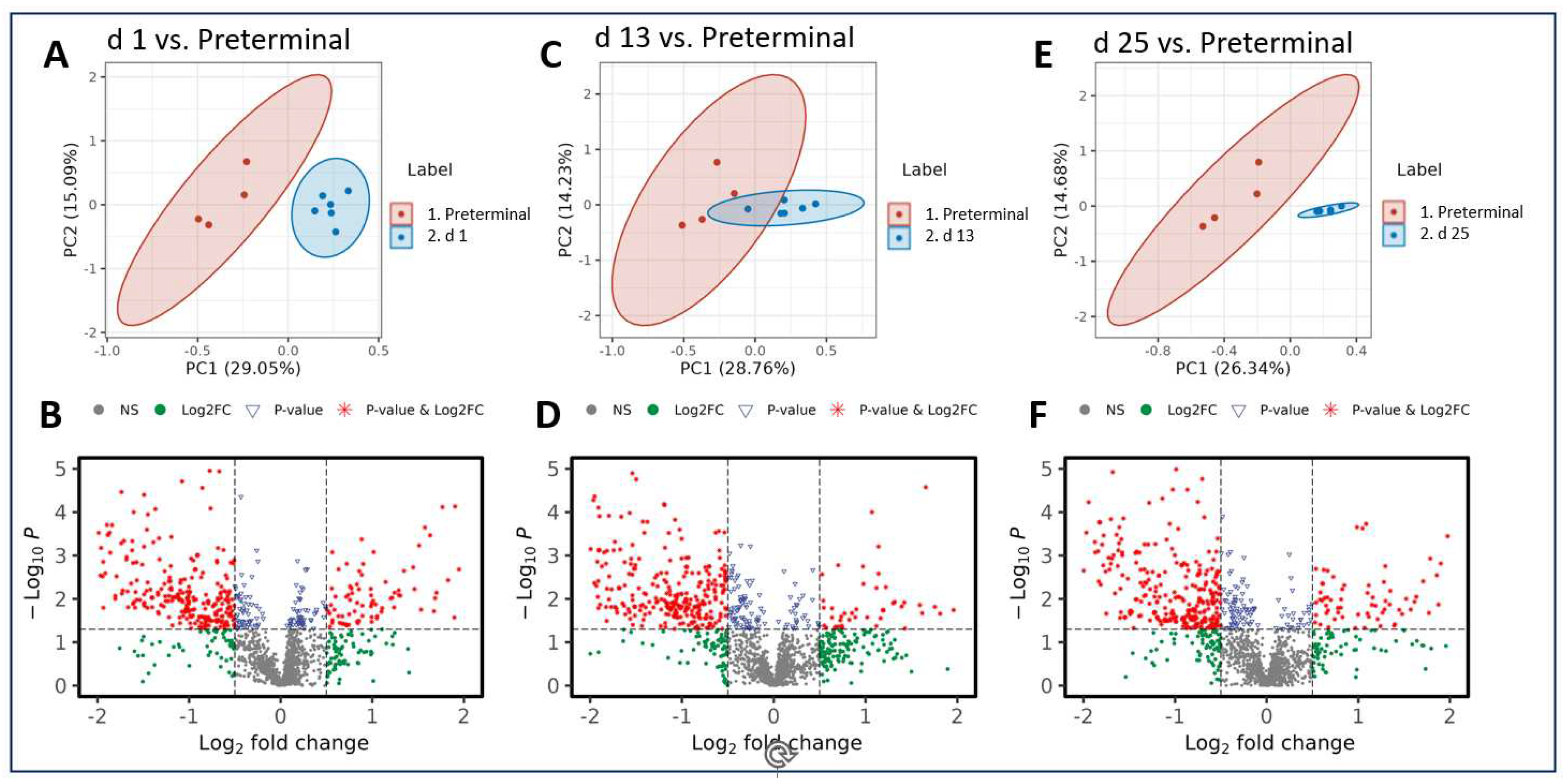

As was seen in the pre-irradiation comparisons, radiation-induced metabolic perturbations were downregulated as the study progressed. However, the comparison between the preterminal timepoint to the post-irradiation timepoints revealed that the majority of metabolites in these comparisons were upregulated.

Notably, there are more statistically significant disruptions in the plasma samples of preterminal NHPs compared with those collected at the day 1, 13, and 25 timepoints (

Figure 4). Three metabolites putatively involved in steroidal hormone biosynthesis appear in greater abundance in the preterminal NHP samples compared with all other post-irradiation timepoints tested, with fold changes ranging from 1.47 to 9.49. These upregulated metabolites include 5alpha-pregnane-3,20-dione, 17alpha-hydroxypregnenolone, and allopregnanolone, and results are summarized in

Table 2. Additionally, a number of plasma metabolites were detected at lower abundances in preterminal NHP samples compared with samples collected at all other timepoints. Seven metabolites including 5alpha-THDOC, phosphatidate, glycero-3-phosphocholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, 17-hydroxylinolenic acid, androsterone, and testosterone were consistently downregulated and are summarized in

Table 3. Fold-changes for these seven metabolites ranged from 0.678 to 0.176, representing percent decreases from 32.2 to 82.4, respectively. Pathway enrichment analysis suggest that these metabolites seem to be involved in choline, alpha-linolenate, glycerophospholipid, and steroid hormone synthesis and metabolism (

Supplementary Figures 4–6, and Supplementary Tables 6 – 8). Additional set of metabolites putatively associated with a variety of metabolic pathways and mechanisms were significantly altered when examining pairwise the preterminal and other timepoints.

4. Discussion

Biomarkers, or biological markers, are quantifiable biological characteristics that can be used as a surrogate to assess overall health of an individual at a certain point in time and can include proteins, metabolites, cytokines, etc. Biomarkers are of particular interest in radiation biology, as they can be used to assess the extent of radiation exposure, predict lethality, and to assess drug efficacy in the development of radiation countermeasures. Given that radiation is known to induce damage at the genetic level, the expression of these changes can be viewed downstream in the form of metabolomic changes. Identifying the metabolic pathways involved in the cellular response to radiation exposure is therefore essential for evaluating the overall health of an individual and for the development of radiation countermeasures, and will potentially allow for these particular metabolites and pathways to be targeted for the development of radiation countermeasures [

32]. Metabolomic changes induced by acute radiation exposure have been well-documented in our previous studies; we have investigated metabolic changes in both serum and tissue samples in murine [

33,

34,

35] and NHP [

36,

37,

38,

39] models that were exposed to

60Co total-body γ-radiation, and also in NHPs exposed to partial-body LINAC-derived X-ray exposure [

40]. In these studies, various radiation MCMs that were being developed for prophylactic or mitigative use were administered to assess the effects on metabolomics, including Ex-Rad [

25], BIO 300 [

30,

41], amifostine [

33,

34,

35], and GT3 [

42,

43]. The Ex-Rad [

25] and GT3 [

40,

42] studies were performed with an NHP model, while the amifostine [

33,

34,

35] studies were performed in a murine model. However, this is the first study where we have attempted to identify metabolic shifts present immediately prior to death in irradiated, preterminal animals.

In this study, fourteen male NHPs were exposed to 7.2 Gy total-body gamma irradiation, and were monitored for 60 days post-irradiation. The main goal of this study was to characterize the metabolomic perturbations involved in the preterminal state following IR exposure. Plasma samples were collected throughout the course of the study, and were analyzed to assess changes in metabolomic profiles as a function of time in the survivor and pre-terminal cohort. As this study used a lethal dose of radiation (LD70/60), a few NHPs became moribund and were deemed candidates for early euthanasia. In an effort to catalog the preterminal phenotype of NHPs on the verge of death, blood samples were taken from these animals immediately prior to euthanasia. Comparisons were performed to assess any significant changes in pre-irradiation or preterminal samples.

As expected, radiation induced a cascade of significant metabolic changes that affected several key metabolic pathways. The alpha-lenolenic acid, choline, and glycerophospholipid metabolic pathways were significantly altered by radiation exposure when comparing post-irradiation samples to pre-irradiation samples. In preterminal samples, a greater degree of metabolic dysregulation was observed in comparison to all other timepoints tested. Both the glycerophospholipid metabolism and steroid hormone and biosynthesis pathways were significantly dysregulated in preterminal animals. Interestingly, glycerophospholipid metabolism was found to be dysregulated both in irradiated NHPs as well as preterminal NHPs. This pathway is of particular interest, as radiation is known to induce lipid peroxidation and dyslipidemia resulting in cellular damage [

44]. Both the glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway and the steroid hormone and biosynthesis pathway are involved in inflammatory response, and several other studies have demonstrated dysregulation in these pathways is induced by radiation exposure [

25,

45,

46]. Three steroid hormones, 5alpha-pregnane-3,20-dione, 17alpha-hydroxypregnenolone, and allopregnanolone, were found to be significantly upregulated in preterminal NHPs. The steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway seems to be particularly sensitive to radiation exposure, which may indicate that dysregulation to this specific pathway may increase lethality in irradiated animals [

25,

35,

45]. These results suggest that early perturbations of these specific pathways and metabolites may be representative of the preterminal state of lethally irradiated NHPs.

Evident from this analysis, while exploratory, strongly supports the notion that plasma samples from preterminal NHPs exhibit a number of significant metabolomic alterations or disruptions that can be used preemptive indicators of radiation lethality. Based on putative metabolic feature identities, the same or similar pathways were disrupted following irradiation as were disrupted at the preterminal stage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the metabolic profiles in irradiated NHP samples collected from moribund (preterminal) NHPs to identify the metabolites significantly altered just prior to death. Additionally, another study is being conducting using similar preterminal samples from a large number of NHPs irradiated with more than one dose of cobalt-60 gamma-radiation. Continued research into the preterminal state of moribund NHPs is needed to further identify metabolites and pathways that can be targeted for the development of various therapeutic strategies to treat ARS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Study design: VKS; Performance of the study: OOF, SYW, VKS; Data acquisition, curation and analysis: VKS, AKC, ADC, OOF, SYW, JBT; Drafting of the manuscript: ADC, VKS, AKC, OOF, SYW; Revision of manuscript content: VKS, AKC, ADC, OOF, SYW; Supervision: VKS; Funding acquisition: VKS. All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.d.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the research support from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences/Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (grant # AFR-B4-10978 and 12080) to VKS.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Radiation Science Department for dosimetry and radiation exposure to the animals, and to the staff of Veterinary Science Department for animal care. The authors would like to acknowledge the Metabolomics Shared Resource in Georgetown University (Washington, DC, USA) partially supported by NIH/NCI/CCSG grant P30-CA051008.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Disclaimer

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the Department of Defense. The mention of specific therapeutic agents does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Department of Defense, and trade names are used only for the purpose of clarification.

Ethics Statement

All procedures were approved by AFRRI and the Department of Defense Animal Care and Use Review Office (ACURO). This study was carried out in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health [

22].

References

- Health and Human Services. HHS enhances nation’s health preparedness for radiological threats. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/10/06/hhs-enhances-nation-s-health-preparedness-radiological-threats.html (accessed on October 20).

- Gosden, C.; Gardener, D. Weapons of mass destruction--threats and responses. BMJ 2005, 331, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, R.P.; Armitage, J.O.; Hashmi, S.K. Emergency response to radiological and nuclear accidents and incidents. British journal of haematology 2021, 192, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, R.P.; Baranov, A. If the unlikely becomes likely: Medical response to nuclear accidents. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 2011, 67, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, I.A.; Guskova, A.K.; Mettler, F.A. Medical Management of Radiation Accidents; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Biodefense: 10 years after reinventing Project BioShield. Science 2011, 333, 1216–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, P.K. Project BioShield: What it is, why it is needed, and its accomplishments so far. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2007, 45 Suppl 1, S68-72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Project BioShield annual report, January 2014 – December 2014. Available online: https://www.medicalcountermeasures.gov/media/36816/pbs-report-2014.pdf (accessed on February 29).

- Hall, E.J.; Giaccia, A.J. Radiobiology for the Radiologist, 7th ed.; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo, A.L.; Maher, C.; Hick, J.L.; Hanfling, D.; Dainiak, N.; Chao, N.; Bader, J.L.; Coleman, C.N.; Weinstock, D.M. Radiation injury after a nuclear detonation: Medical consequences and the need for scarce resources allocation. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2011, 5 Suppl 1, S32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waselenko, J.K.; MacVittie, T.J.; Blakely, W.F.; Pesik, N.; Wiley, A.L.; Dickerson, W.E.; Tsu, H.; Confer, D.L.; Coleman, C.N.; Seed, T.; et al. Medical management of the acute radiation syndrome: Recommendations of the Strategic National Stockpile Radiation Working Group. Annals of internal medicine 2004, 140, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coy, S.L.; Cheema, A.K.; Tyburski, J.B.; Laiakis, E.C.; Collins, S.P.; Fornace, A., Jr. Radiation metabolomics and its potential in biodosimetry. International journal of radiation biology 2011, 87, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Seed, T.M.; Cheema, A.K. Metabolomics-based predictive biomarkers of radiation injury and countermeasure efficacy: Current status and future perspectives. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2021, 21, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Fornace, A.J., Jr.; Laiakis, E.C. Metabolomic applications in radiation biodosimetry: exploring radiation effects through small molecules. International journal of radiation biology 2017, 93, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, R.D.; Goans, R.E.; Blain, P.G.; Thomas, S.H. Diagnosis and treatment of polonium poisoning. Clinical toxicology 2009, 47, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Fell, T.; Leggett, R.; Lloyd, D.; Puncher, M.; Youngman, M. The polonium-210 poisoning of Mr Alexander Litvinenko. Journal of radiological protection : official journal of the Society for Radiological Protection 2017, 37, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathwani, A.C.; Down, J.F.; Goldstone, J.; Yassin, J.; Dargan, P.I.; Virchis, A.; Gent, N.; Lloyd, D.; Harrison, J.D. Polonium-210 poisoning: a first-hand account. Lancet 2016, 388, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. The radiological accident in Goiânia. Available online: http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/Pub815_web.pdf (accessed on October 2).

- Da Silva, F.C.; Hunt, J.G.; Ramalho, A.T.; Crispim, V.R. Dose reconstruction of a Brazilian industrial gamma radiography partial-body overexposure case. Journal of radiological protection : official journal of the Society for Radiological Protection 2005, 25, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Olabisi, A.O. Nonhuman primates as models for the discovery and development of radiation countermeasures. Expert opinion on drug discovery 2017, 12, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schule, S.; Gluzman-Poltorak, Z.; Vainstein, V.; Basile, L.A.; Haimerl, M.; Stroszczynski, C.; Majewski, M.; Schwanke, D.; Port, M.; Abend, M.; et al. Gene Expression Changes in a Prefinal Health Stage of Lethally Irradiated Male and Female Rhesus Macaques. Radiation research 2023, 199, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Wise, S.Y.; Carpenter, A.D.; Olsen, C.H. Determination of lethality curve for cobalt-60 gamma-radiation source in rhesus macaques using subject-based supportive care. Radiation research 2022, 198, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Singh, J.; Varghese, R.; Zhang, Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Cheema, A.K.; Singh, V.K. Transcriptome of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) exposed to total-body irradiation. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Girgis, M.; Wise, S.Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Seed, T.M.; Maniar, M.; Cheema, A.K.; Singh, V.K. Analysis of the metabolomic profile in serum of irradiated nonhuman primates treated with Ex-Rad, a radiation countermeasure. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 11449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, A.J.; Bergmann, J.N.; Albrecht, M.T.; Singh, V.K.; Homer, M.J. Model for evaluating antimicrobial therapy to prevent life-threatening bacterial infections following exposure to a medically significant radiation dose. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2022, 66, e0054622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Li, Y.; Moulton, J.; Girgis, M.; Wise, S.Y.; Carpenter, A.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Singh, V.K. Identification of novel biomarkers for acute radiation injury using multiomics approach and nonhuman primate model. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 2022, 114, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition. Available online: https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/2020-Euthanasia-Final-1-17-20.pdf (accessed on December 29).

- Singh, V.K.; Kulkarni, S.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Wise, S.Y.; Newman, V.L.; Romaine, P.L.; Hendrickson, H.; Gulani, J.; Ghosh, S.P.; Kumar, K.S.; et al. Radioprotective efficacy of gamma-tocotrienol in nonhuman primates. Radiation research 2016, 185, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Girgis, M.; Jayatilake, M.; Serebrenik, A.A.; Cheema, A.K.; Kaytor, M.D.; Singh, V.K. Pharmacokinetic and metabolomic studies with a BIO 300 oral powder formulation in nonhuman primates. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 13475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Li, Y.; Singh, J.; Johnson, R.; Girgis, M.; Wise, S.Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Kaytor, M.D.; Singh, V.K. Microbiome study in irradiated mice treated with BIO 300, a promising radiation countermeasure. Anim Microbiome 2021, 3, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.S.; Uppal, M.; Randhawa, S.; Cheema, M.S.; Aghdam, N.; Usala, R.L.; Ghosh, S.P.; Cheema, A.K.; Dritschilo, A. Radiation metabolomics: Current status and future directions. Frontiers in oncology 2016, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, A.; De Lima Leite, A.; Payne, T.; Bhinderwala, F.; Woods, J.; Singh, V.K.; Powers, R. Radiation exposure induces cross-species temporal metabolic changes that are mitigated in mice by amifostine. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, A.K.; Li, Y.; Girgis, M.; Jayatilake, M.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Wise, S.Y.; Seed, T.M.; Singh, V.K. Alterations in tissue metabolite profiles with amifostine-prophylaxed mice exposed to gamma radiation. Metabolites 2020, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Li, Y.; Girgis, M.; Jayatilake, M.; Simas, M.; Wise, S.Y.; Olabisi, A.O.; Seed, T.M.; Singh, V.K. Metabolomic studies in tissues of mice treated with amifostine and exposed to gamma-radiation. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Hinzman, C.P.; Mehta, K.Y.; Hanlon, B.K.; Garcia, M.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Singh, V.K. Plasma derived exosomal biomarkers of exposure to ionizing radiation in nonhuman primates. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Laiakis, E.C.; Garcia, M.; Fornace, A.J., Jr.; Singh, V.K. Nonhuman primates with acute radiation syndrome: Results from a global serum metabolomics study after 7.2 Gy total-body irradiation. Radiation research 2018, 190, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Laiakis, E.C.; Singh, V.K.; Fornace, A.J. Lipidomic signatures of nonhuman primates with radiation-induced hematopoietic syndrome. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, A.K.; Mehta, K.Y.; Rajagopal, M.U.; Wise, S.Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Singh, V.K. Metabolomic studies of tissue injury in nonhuman primates exposed to gamma-radiation. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.D.; Li, Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Wise, S.Y.; Petrus, S.A.; Janocha, B.L.; Cheema, A.K.; Singh, V.K. Metabolomic profiles in tissues of nonhuman primates exposed to total- or partial-body radiation. Radiation research 2023, (in press). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Mehta, K.Y.; Santiago, P.T.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Kaytor, M.D.; Singh, V.K. Pharmacokinetic and metabolomic studies with BIO 300, a nanosuspension of genistein, in a nonhuman primate model. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Laiakis, E.C.; Fornace, A.J., Jr.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Singh, V.K. A metabolomic serum signature from nonhuman primates treated with a radiation countermeasure, gamma-tocotrienol, and exposed to ionizing radiation. Health Phys 2018, 115, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Mehta, K.Y.; Fatanmi, O.O.; Wise, S.Y.; Hinzman, C.P.; Wolff, J.; Singh, V.K. A Metabolomic and lipidomic serum signature from nonhuman primates administered with a promising radiation countermeasure, gamma-tocotrienol. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, K.; Baghel, R.; Dhariwal, S.; Sharma, A.; Bakhshi, R.; Rana, P. Metabolomics and transcriptomics based multi-omics integration reveals radiation-induced altered pathway networking and underlying mechanism. npj Systems Biology and Applications 2023, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, M.; Rajagopal, M.; Gill, K.; Li, Y.; Bansal, S.; Sridharan, V.; Tyburski, J.B.; Boerma, M.; Cheema, A.K. Identification of plasma lipidome changes associated with low dose spacetType radiation exposure in a murine model. Metabolites 2020, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Laiakis, E.C.; Mak, T.D.; Astarita, G.; Authier, S.; Wong, K.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. A lipidomic and metabolomic serum signature from nonhuman primates exposed to ionizing radiation. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society 2016, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental design to assess changes in plasma metabolic profiles in NHPs exposed to 7.2 Gy TBI from samples collected pre-irradiation (day (d) -7), d 1, d 13, d 25, or immediately prior to death (preterminal).

Figure 1.

Experimental design to assess changes in plasma metabolic profiles in NHPs exposed to 7.2 Gy TBI from samples collected pre-irradiation (day (d) -7), d 1, d 13, d 25, or immediately prior to death (preterminal).

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot (Panel A) and heat map (Panel B) show radiation induced robust changes in metabolic profiles in pre-irradiation, day (d) 1, d 13, d 25, or preterminal samples. Of note; the plasma metabolic profiles of the preterminal samples are strikingly different compared to other study groups.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot (Panel A) and heat map (Panel B) show radiation induced robust changes in metabolic profiles in pre-irradiation, day (d) 1, d 13, d 25, or preterminal samples. Of note; the plasma metabolic profiles of the preterminal samples are strikingly different compared to other study groups.

Figure 3.

PCA and volcano plots illustrating metabolic disruptions caused by radiation at days (d) 1 (A, B), 13 (C, D), and 25 (E, F), respectively.

Figure 3.

PCA and volcano plots illustrating metabolic disruptions caused by radiation at days (d) 1 (A, B), 13 (C, D), and 25 (E, F), respectively.

Figure 4.

PCA and volcano plots demonstrating metabolic alterations when comparing the preterminal stage to the post-irradiation stages at day (d) 1 (A, B) , d 13 (C, D), and d 25 (E, F), respectively.

Figure 4.

PCA and volcano plots demonstrating metabolic alterations when comparing the preterminal stage to the post-irradiation stages at day (d) 1 (A, B) , d 13 (C, D), and d 25 (E, F), respectively.

Table 1.

Downregulated plasma metabolites when comparing pre-irradiation samples to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

Table 1.

Downregulated plasma metabolites when comparing pre-irradiation samples to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

| |

|

|

|

p-value |

| KEGG ID |

Comparison |

FC |

Log2(FC) |

WSR Test |

MWU Test |

| Phosphatidylcholine |

d 1 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.62122 |

-0.68682 |

< 0.05 |

0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.87591 |

-0.19114546 |

0.24 |

0.292 |

| |

d 25 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.79989 |

-0.32212648 |

< 0.05 |

0.026 |

| Glycero-3-phosphocholine |

d 1 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.47664 |

-1.06903 |

< 0.05 |

<0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.6579 |

-0.60405978 |

< 0.05 |

0.025 |

| |

d 25 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.43917 |

-1.18714859 |

< 0.05 |

<0.001 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine |

d 1 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.59364 |

-0.75234 |

< 0.05 |

0.005 |

| |

d 13 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.70821 |

-0.49775088 |

0.24 |

0.061 |

| |

d 25 vs. Pre-irradiation |

0.49562 |

-1.01269369 |

< 0.05 |

0.003 |

Table 2.

Upregulated plasma metabolites in preterminal samples compared to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

Table 2.

Upregulated plasma metabolites in preterminal samples compared to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

| |

|

|

|

p-value |

| KEGG ID |

Comparison |

FC |

Log2(FC) |

WSR Test |

MWU Test |

| 5alpha-Pregnane-3,20-dione |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

1.8672 |

0.900876466 |

0.01 |

0.002 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

1.5528 |

0.634872023 |

0.02 |

0.017 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

1.9819 |

0.986884171 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| 17alpha-Hydroxypregnenolone |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

9.4901 |

3.246423289 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

2.4951 |

1.319097638 |

0.01 |

0.012 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

3.7344 |

1.900876466 |

0.01 |

0.002 |

| Allopregnanolone |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

1.715 |

0.778208576 |

0.01 |

0.004 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

1.4744 |

0.560127976 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

1.6643 |

0.734915511 |

0.04 |

0.015 |

Table 3.

Downregulated plasma metabolites in preterminal samples compared to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

Table 3.

Downregulated plasma metabolites in preterminal samples compared to day (d) 1, d 13, and d 25 samples.

| |

|

|

|

p-value |

| KEGG ID |

Comparison |

FC |

Log2(FC) |

WSR Test |

MWU Test |

| 5alpha-THDOC |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.21841 |

-2.19488918 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.3371 |

-1.56875147 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.30752 |

-1.70124785 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| Phosphatidate |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.17627 |

-2.50414114 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.25821 |

-1.95338322 |

0.02 |

0.004 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.33539 |

-1.57608842 |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

| Glycero-3-phosphocholine |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.51933 |

-0.94527653 |

0.11 |

0.011 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.37625 |

-1.41023651 |

0.02 |

0.007 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.56364 |

-0.8271541 |

0.11 |

0.025 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.56565 |

-0.82201844 |

0.04 |

0.026 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.47415 |

-1.07658456 |

0.02 |

0.025 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.67753 |

-0.56164327 |

0.35 |

0.002 |

| 17-Hydroxylinolenic acid |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.35181 |

-1.5071316 |

0.01 |

0.003 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.33201 |

-1.5907014 |

0.04 |

0.012 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.47845 |

-1.06355993 |

0.04 |

0.022 |

| Androsterone |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.52337 |

-0.93409687 |

0.01 |

0.001 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.65955 |

-0.60044606 |

0.038 |

0.04 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.69581 |

-0.52323 |

0.067 |

0.095 |

| Testosterone |

d 1 vs. Preterminal |

0.62021 |

-0.68917131 |

0.114 |

0.018 |

| |

d 13 vs. Preterminal |

0.54735 |

-0.86946444 |

0.019 |

0.01 |

| |

d 25 vs. Preterminal |

0.64174 |

-0.63993919 |

0.114 |

0.025 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).