3.1. The Zebra Mussel Discovery and its Pre-Anthropocene Range

Peter-Simon Pallas (1741–1811), a Russian naturalist of German origin, was the first zoologist to identify the zebra mussel as a distinct species and provide its scientific description. The place and date of this discovery is known with exhaustive exactness. During his long travel throughout ‘various provinces of the Russian Empire’ (1768–1774) [

30], Pallas explored the lower courses of the Volga and Ural River basins. Pallas found the specimens of a new species 12.08.1769, in a small oxbow near the Budarin Forpost settlement – a small Cossack camp on the territory of the modern West-Kazakhstan Region of Republic of Kazakhstan ([

30] p. 368). Shortly after that, Pallas found the same species near Kalenoi Forpost, another Cossack camp on the Ural River ([

30], p. 375), and, finally, in the Caspian Sea near the Kamennyi (= Stony) Island, between 26 and 31 August 1769 ([

30], p. 435). Pallas described this new species under the name

Mytilus polymorphus, classifying it thus as a member of the genus

Mytilus, which includes chiefly marine and brackish-water bivalves. Only in 1835 a separate genus (

Dreissena) was established for this species by a Belgian zoologist Pierre-Joseph Van Bénéden (1809–1894), then working in Louvain [

31]. The generic name is an eponym. The new genus was dedicated to J.H. Dreissens, a pharmacist in Mazeik Town (then in the Netherlands; nowadays it is Maaseik, Limbourg Province, Belgium), who collected a sample of specimens of this mussel in a local channel and gave it to Van Bénéden for study [

31].

The fossil record of

D. polymorpha is comparatively rich [

3,

4,

5,

31,

32,

33]. During the interglacial periods of the Pleistocene epoch, the zebra mussel could spread widely and was distributed much broader than in the early Holocene; its range occupied the entire basins of the Danube, Volga, Don, and Dnieper rivers (

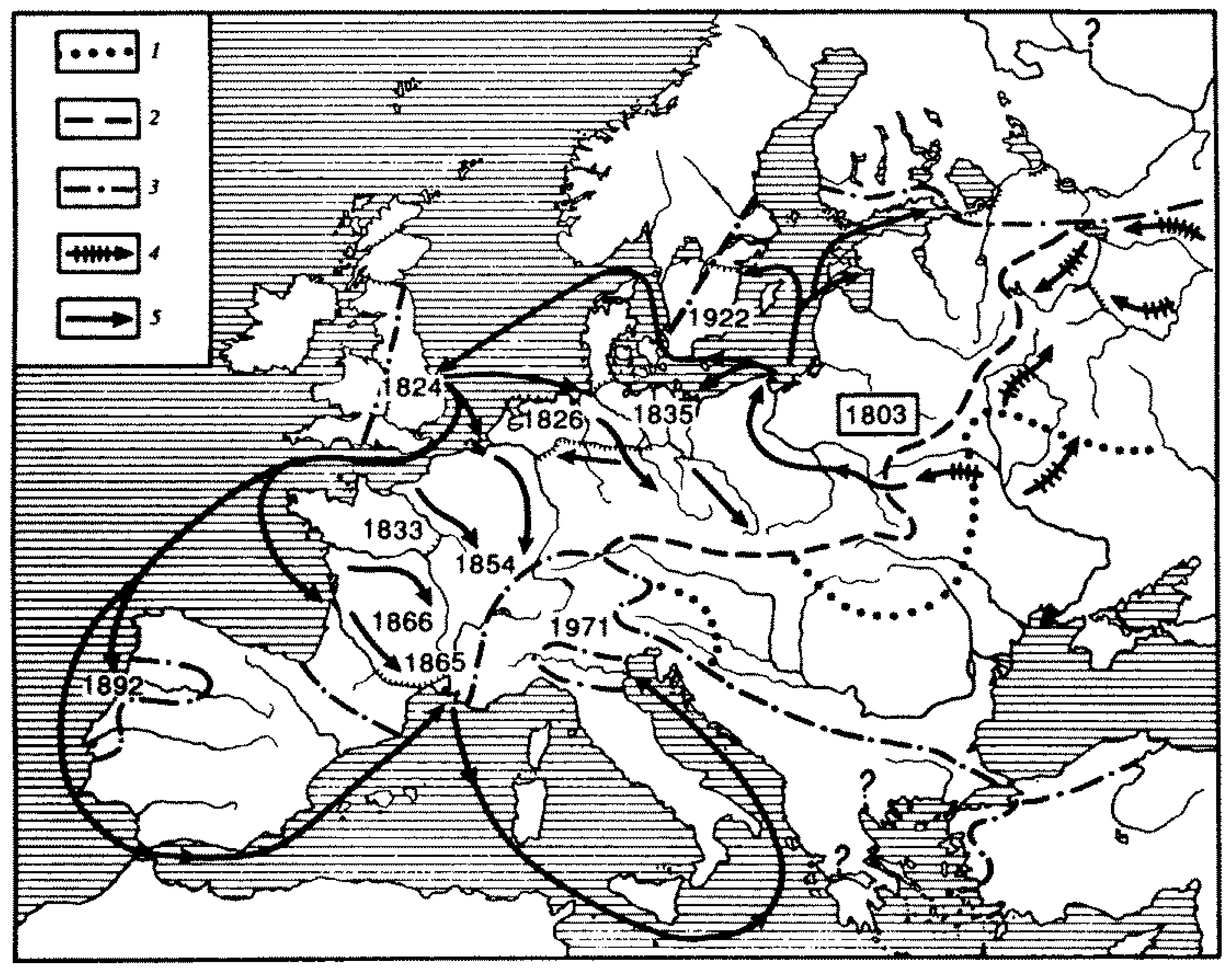

Figure 2). However, this species was unable to penetrate other large river systems of Europe due to a lack of basin interconnections [

3]. As a result of the last Quaternary glaciation (Würmian glacial stage), the range of

D. polymorpha was significantly reduced. In the early Holocene, it covered the lower courses of the Volga, Don, Ural and Danube river basins, from where mollusks began to slowly spread upstream, restoring their lost range. Already in the Middle Ages, river navigation could speed up this process [

3].

The turning point in the history of the

D. polymorpha invasion is associated with the construction of canals that connected the Volga and Dnieper basins with the basins of rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea. The first constructions of this sort dated back to the Peter the Great epoch in Russia. According to Andrusov [

31], the Vyshevolotsk channel system, opened in 1709, could serve as the first corridor of invasion of

D. polymorpha into Central Europe. It connected the Volga basin with the Baltic Sea basin through the Lake Ladoga and the Neva River. This point of view was questioned by many authors, who proposed another corridor – the Oginsk Channel, opened in 1803 [

2,

3,

34]. It connected the Dnieper basin with the Neman River system. The arguments against the Vyshevolotsk channel system as the “window to Europe” for the zebra mussel included the relatively low water temperature in the Neva River, which this mussel probably cannot sustain, and the full absence of records of

D. polymorpha in the Baltic Sea basin prior to the 1820s [

3]. Indeed, the first record of this species in the vicinities of St.-Petersburg (the Neva River basin) was published only in 1883 [

2].

The first scientific records of the zebra mussel outside its native range date back to the mid-1820s, when it was found in England (in 1824) [

35] and in the former East Prussia (in 1825) [

36]. Subsequently, this bivalve was registered in many European countries, and at the end of the 19

th its invasive range already covered some parts of the Iberian Peninsula (see

Figure 2).

3.2. The European Naturalists’ Response to D. polymorpha Invasion: England

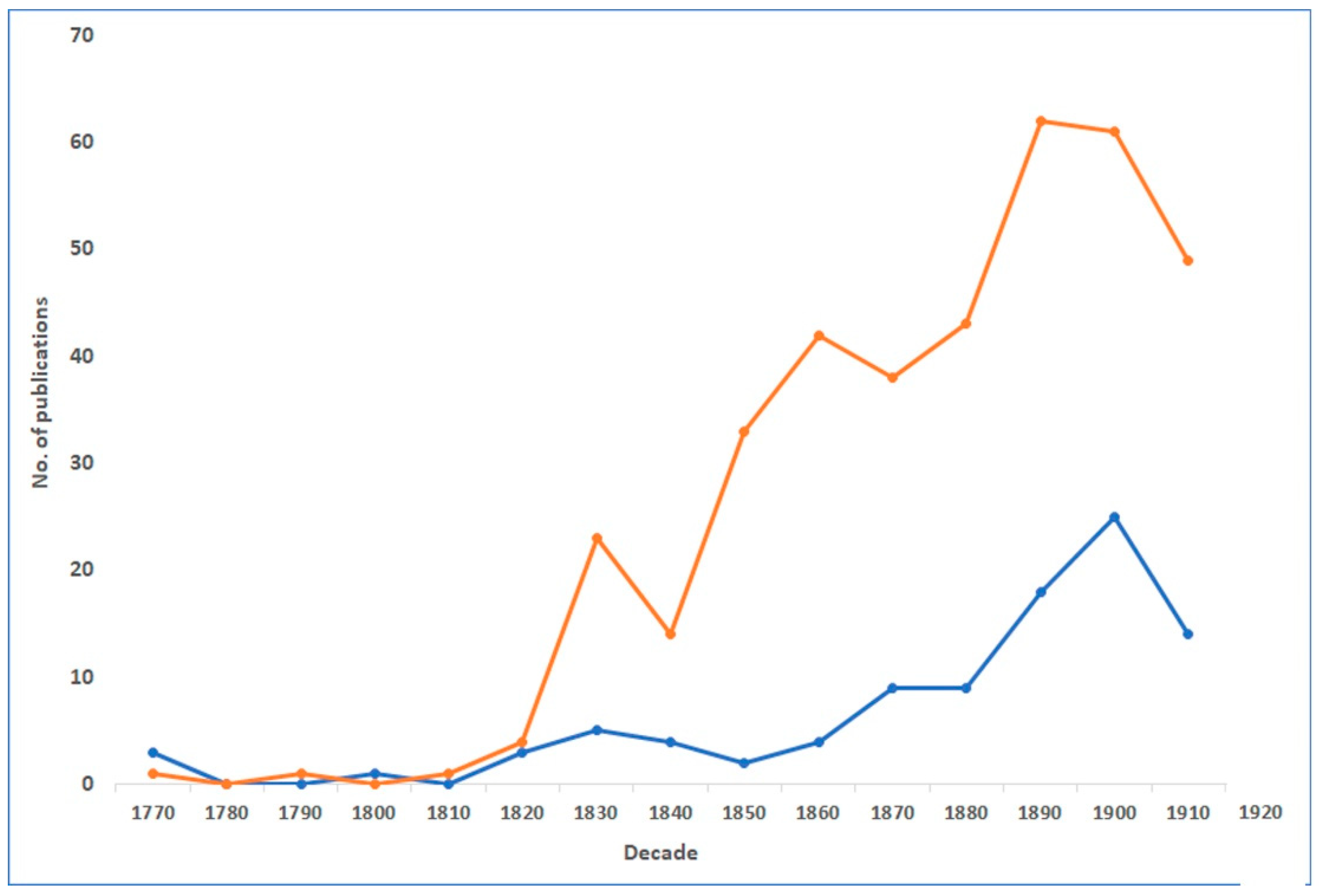

The bibliography of the

D. polymorpha studies in Europe shows that prior to the 1830s, the number of publications on this species remained very low. The decade starting from 1830 witnessed a sharp increase in the naturalists’ interest in this mussel (see

Figure 1), which can be surely related to the first findings of the zebra mussel in some parts of Europe. Already around 1830 this species became a subject of close attention of zoologists in Britain, Belgium, Germany, and several other countries.

The United Kingdom was a country, where one of the earliest findings of the invasive mussel was made (

Table 1). The exact date of its penetration to the British Isles remains unknown, but one can assume that it happened 5-10 years before 1825, when the first scientific publication on this subject appeared [

35]. Its author, James De Carle Sowerby (1787–1871), is well known as a palaeontologist, described, among others, many species of fossil Mollusca. According to his report,

D. polymorpha were living in abundance in Commercial Docks on the Thames, in Rotherhite (nowadays it is a district of London), where a local gentleman used them as bait for perch [

35]. Sowerby correctly identified this find to

Mytilus polymorphus (though he ascribed the authorship of this name to Gmelin, not to Pallas) living in Russia and in the Danube River basin, however, did not state that this bivalve is non-indigenous to the British Isles. He remarked only that “the British specimens are much larger and finer than any foreign ones I have seen”. The latter remark shows that specimens of

Dreissena from the continental Europe were accessible for a British naturalist, either from a public museum or a private collection.

In the same year, however, the invasive nature of the zebra mussel in the UK was acknowledged by another British zoologist, John Edward Gray (1800–1875), a prominent student of Mollusca. In his paper devoted to the classification of some bivalve genera, Gray mentioned this species under the name

Mytilus ?

volgensis and added that “it most likely have been introduced with timber from the Volga” [

37]. More importantly, Gray tried to understand how the animal could have reached the British Isles and suggested that the zebra mussel may sustain for a relatively lengthy period out of water. The naturalist claimed that he kept an individual of

Dreissena “for three weeks, when it was still healthy” [

37]. It was, perhaps, one of the earliest instances of an experimental approach to the problem of biological invasions, attempted purposely and with a full understanding of its significance.

The subsequent British literature on

D. polymorpha can be roughly divided into two parts. The first part includes a number of relatively short research notes documenting new or remarkable observations of the zebra mussel in different regions of that country e.g., [

38,

39,

40]. Some of these notes were rather concise, sometimes not lengthier than 8–10 lines, in which the circumstances of the findings were described, with relevant details. A typical (and unabridged) example of such record note is given below:

“Some eight years ago, while angling in an old milldam at Toton, Notts, with my brother, he pulled up on his hook a specimen of

Dreissena polymorpha, adhering to a stone. The dam is supplied by the Erewash, a small shallow stream which joins the Trent nearly a mile from the place, that river being the nearest navigable water. I afterwards found numbers of these Mollusks adhering to the stones underneath the waterfall of a pond at Lentou, near Nottingham, to which they must have gone up a very small brook fully a mile from a canal; in which, however, though I have frequently searched, I have never found them. — George Wolley; 9, Cambridge Street, Liverpool, February 23rd, 1846” [

38].

Table 1.

The dates of the first records of

Dreissena polymorpha in various countries of Western and Central Europe (1800–1920s). Compiled after several sources [

2,

3,

4,

5,

26,

31].

Table 1.

The dates of the first records of

Dreissena polymorpha in various countries of Western and Central Europe (1800–1920s). Compiled after several sources [

2,

3,

4,

5,

26,

31].

| Year (decade) |

Country (Basin) |

Year (decade) |

Country (Basin) |

| Around 1790 |

Hungary |

1840 or 1843 |

Denmark |

| The late 1800s |

Poland |

1855 |

The Seine River, France |

| 1824 |

England |

1856 |

The Loire River, France |

| 1825 |

East Prussia |

Near 1861 |

South Germany (Bavaria) |

| 1826 |

The Netherlands |

1865 |

The Rhone River, France |

| 1827 or 1828 |

Central Germany (near Berlin) |

1866 |

The Garonne River, France |

| 1833 or 1834 |

Belgium |

1892 |

Portugal** |

| 1833 or 1834 |

Scotland |

1896 |

The Severnaya Dvina River basin (the upper course), Russia |

| 1835 |

Northern Germany (the lower Elbe basin) |

1890s |

The Czech Republic |

| 1838 |

France, the Nord Departement* |

1922 |

Southern Sweden |

It is not always clear from such laconic reports, if their authors were aware of the invasive origin of the discussed species and whether they realized the need for a precise documentation of such findings, which would help to trace the spread of

D. polymorpha through the country. Most probably, the authors wished to inform their peers of record of a new and interesting species and did not intend to contribute to the better understanding of the invasion process. However, some of them seemed to give a close attention to the new naturalizing species and were deeply impressed by the pace and efficacy of its spread. Thus, the Reverend Berkeley as early as 1836 stated that the zebra mussel ‘is now found in almost every part of Europe, in inland seas, marshes, canals, tanks, and running streams’ ([

39], p. 573). Even a fast examination of

Figure 2 and

Table 1 will show how exaggerated this statement was. In 1836, the ‘wandering’ mussel was found only in a few localities beyond its original range.

The lists of species of a local malacofauna, where the zebra mussel was included e.g., [

41,

42], must be also classified as belonging to the first category.

The amateur naturalists were very numerous in the Great Britain of that time, and most of them were educated men, including physicians, engineers, officers, and (rather commonly) churchmen and gentlemen of independent means [

43]. Many of them now would be called the ‘citizen scientists’. However, the vast majority of these naturalists did not produce voluminous monographs on mollusks and other groups of animals, and their literary production often was represented by such research notes and ‘letters to editor’. The scientific interests of such men were very broad. For example, George Wolley in 1846 published in the same journal two more notes, entitled «Anecdote of the stoat’s preying upon bats” and “Exotic spiders imported in dye-woods” (the latter one demonstrates Wolley’s attention to the introduced species of animals).

These publications, however, served to the accumulation of the primary data and as the empirical material for generalizations made by more ‘advanced’ amateurs or by professed scientists, affiliated with universities or museums (the number of the latter was rather low due to the deficiency of teaching and researcher positions). Roebuck [

44] published, at the very end of the studied period (in 1921), a paper, where these scattered distributional records of the 19

th – early 20

th century were reviewed and summarized.

The second group of the British literary source is formed by comprehensive works, in which the whole aquatic malacofauna of the country was reviewed. Some of these publications were high-standard taxonomic monographs aimed at professional zoologists e.g., [

45,

46,

47], others were popular guidelines for amateurs, less abundantly illustrated and much more accessible, both in terms of price and content e.g., [

48,

49,

50]. Generally, such publications provided a more or less detailed description of the shell and, sometimes, internal morphology of

Dreissena and gave an outline of its current distribution in the country. However, the questions of invasion ecology and dispersal mechanisms of the species have rarely been addressed in detail by their authors. As for the dispersal, most authors repeated the hypotheses discussed in works of Gray, Strickland, and other authorities who wrote about

D. polymorpha in England. In most cases, the non-indigenous status of this mollusk in England was fully accepted, and, for instance, Forbes & Hanley ([

45], p. 167) called it “a species of ancient origin, and one of the members of the old Aralo-Caspian fauna”. The most peculiar approach to the problem of

Dreissena in the UK can be found in a monograph on the

‘British conchology’ by Jeffreys (see

Section 3.3).

Hugh Strickland (1811–1853), a prominent English naturalist of that time, authored one of the first special publications on the colonization of the Britain by the zebra mussel. He fully realized the theoretical importance of the study of this invasion both for zoology and geology. Strickland documented a very fast (about two-three years) colonization of the Avon River at Evesham, in Worcestershire by

D. polymorpha and concluded that to a geologist, for instance, the study of this invasion may help to understand “the distribution of organic remains, and the sudden appearance and disappearance of particular species in a given stratum” ([

51], p. 361). The transport of timber was, according to the author, the main means of dispersal of the zebra mussel within England. Strickland also mentioned that some people intentionally

planted the bivalve into novel places, such as around Bristol. Strickland even went as far as to formulate an agenda for the

Dreissena studies in the Great Britain. He expressed this in such words: “It appears desirable to record <…> [the finds of

Dreissena], because it may interest some of our field-naturalists to watch the gradual spread of this species over the kingdom. Its propagation is so astonishingly rapid, that it will probably become, in a few years, one of our commonest British shells” ([

51], p. 363). This prophecy proved true very soon [

52]. In 1845, i.e., only 20 years after the publications of Sowerby and Gray, Brown stated that the invading mussel is so firmly naturalized in Britain that “may fairly been considered a British shell” ([

53], p. 98).

A special aspect of the zebra mussel invasion to the UK (and to other urbanized European country) was its rapid infiltration into water supplies of London and other cities. In Manchester, thriving colonies of

D. polymorpha were detected already around 1850. Dyson reported his observations on these mussels living in the pipes that supplied the city from the nearby waterworks; the mussels also were highly abundant in the reservoir which served as the source of the water [

54]. In the London water supplies,

D. polymorpha was also recorded around 1850. Woodward reported that the mollusks were “noticed in the iron-pipes of London, incrusted with a ferruginous deposit” ([

55], p. 267). Tate [

52] explained the astonishing quantities of

Dreissena in water-pipes by the avoidance of light, which was thought to be characteristic of this mollusk. The harmful effects of the alien bivalve were completely realized in other countries of Europe to the end of the 19

th century and further stimulated the studies of biology and ecology of this species [

56,

57] (

Figure 3).

3.3. The 19th—Early 20th Century Discussion on the Dispersal Mechanism(s) of D. polymorpha in Europe

The first English publications on

D. polymorpha colonizing that country opened a long discussion concerning the ways and routes of the zebra mussel dispersal outside its native range. This debate lasted more than a century and will only be briefly summarized here.

Table 2 provides a concise overview of the diverging hypotheses proposed in the 19

th – early 20

th century. Another source of data on the debate is the monograph on the dispersal of mollusks (“shells”) written by Harry Wallis Kew (1868–1948) in the late 19

th century ([

60], pp. 210-221). It should be noted that almost no author of the studied period insisted that there is the only mechanism of dispersal of

Dreissena; usually two or more possible (and not mutually exclusive) explanations were proposed. Certain naturalists even tried to make experiments with the mussel, attempting to determine how long it can survive out of water [

37], or how quickly the juvenile complete their development to anchor themselves to the substratum [

51]. It seems that the possibility of dispersal of the veligers, i.e., pelagic (swimming) larvae of

Dreissena, was not considered for most of the 19

th century. The first detailed description of the veliger of

D. polymorpha was published by Eugene Korschelt (1858–1946), a German embryologist, in 1891 [

58,

59]. Immediately after that publication, Kew highlighted the exceptional potential of the veligers as the means of

Dreissena dispersal [

60].

70 years of observations made by numerous naturalists in Great Britain led Kew in 1893 to the conclusion that the zebra mussel “is perhaps better fitted for dissemination by man and subsequent establishment than any other fresh-water shell; tenacity of life, unusually rapid propagation, the faculty of becoming attached by a strong byssus to extraneous substances, and the power of adapting itself to strange and altogether artificial surroundings have combined to make it one of the most successful molluscan colonists in the world” ([

60], pp. 219-220).

Whereas most authors acknowledged the non-indigenous status of the zebra mussel in Western and Central Europe, there was an opposition to this widespread view, represented by two prominent malacologists, the British John Gwyn Jeffreys (1809–1885) and the Danish Otto Andreas Lowson Mörch (1828–1878). Both men remained unconvinced that the first findings of

D. polymorpha in England in 1824 marked its recent arrival to the country. In their opinion, “the silence of [the 18

th century] writers” cannot be seen as an ultimate proof: many widespread species of European freshwater mollusks were described scientifically long after Linnaeus, and the new discoveries of the early 19

th century showed that some species of aquatic mollusks could be overlooked by naturalists for decades. In other words, the zebra mussel could be a rare member of the native European fauna, survived in refugia, from which it has started to spread since the inset of the Industrial Revolution and the Napoleonic wars [

46,

61,

62]. Using some obscure descriptions published around 1780, Mörch [

61] argued that

Dreissena might have been distributed in the interior of Germany prior to this year and that these mussels were inhabiting the rivers of the Rhine basin. The upper courses of the Rhine, in Mörch’s opinion, were the source of the zebra mussel colonies found in the Netherlands around 1826 [

61].

In the first half of the 20

th century, this hypothesis was accepted by Zhadin (1896–1974) ([

63], p. 70). This Russian author believed that

Dreissena survived the Pleistocene glacial epochs in refugia situated in North Germany, from where it began its spread to England and other countries of Western Europe. In addition, Zhadin criticized the version that

Dreissena arrived in England with the timber export from Russia. He noted that the lower courses of the Volga and Don River basins, where the Holocene range of the zebra mussel was situated, are almost avoid of forests, and the export timber was yielded in the territories of Russia, located much north, where

D. polymorpha was absent. Equally, Zhadin disputed an old idea that the zebra mussel could arrive in England being attached to the bottoms of marine ships ([

68], pp. 302-303). In his opinion, this hypothesis is untenable since

Dreissena is hardly able to sustain long travel through saline waters, like the waters of the North Sea. However, Zhadin did not reject the key role of canals and other inter-drainage connections, which serve as corridors for the zebra mussel dispersal.

The belief that

D. polymorpha in Western and Central may be a relic of some ancient epochs is not without support today. In 2011, Buynevich et al. [

66] reported the finds of shells of

Dreissena in the southern Baltic Sea coast in deposits formed between 800 and 1200 AD. The authors proposed the “early arrival scenario”, according to which the zebra mussel might have infiltrated the Baltic region more than 1000 years ago, through poorly drained waterways. Medieval river navigation, including Viking river voyages from Constantinople to the Baltic Sea via the Dnieper River and Black Sea, are seen as a human-mediated way of

Dreissena dispersal. Some data supporting this hypothesis one can find in an earlier paper of Deksbakh [

2], who described a find of numerous subfossil shells of the zebra mussel in Belarus. There were other possibilities of the transport of the mussel to Western Europe between 1200 and 1800 [

66]. The existence of the Pleistocene refugia situated in Central and Eastern Europe cannot be ruled out as well. In a series of recent research, the application of the molecular methods helped to identify such refugia for some species of the pearl mussels (Unionidae), another family of freshwater Bivalvia [

8,

67,

68].

3.4. The European Naturalists’ Response to D. polymorpha Invasion: France

According to the recent review by Prié [

26], the first arrival of

D. polymorpha in France must be dated 1852. However, some older authors, for example Locard [

70] and Fischer [

71], gave an earlier date, 1838, when this species was found in the Nord Department (see also Andrusov [

31] and Starobogatov and Andreeva [

3]). The exact date of the invasion remains, thus, disputable. Von Martens [

72] believed that the zebra mussel used at least two invasion corridors to reach France. The first one was the Rhine River (upstream from the Netherlands) and the second was formed by the Sambre-Oise canal system situated at the Belgian-French border. Some modern authors (e.g. [

3]) believe that the source of

Dreissena invasion to France could be the London port, where the species became naturalized 15-20 years earlier (see above). By the end of the 19

th century, the zebra mussel was common throughout the country and mentioned by numerous local naturalists [

70]. Fischer estimated that it took the species about 30 years to become naturalized throughout almost all of France [

71].

The French literature on

Dreissena prior to 1920 was represented by essentially the same genres as English literature: 1) short record notes, documenting the first findings of the mussel in particular regions of France; 2) checklists of local malacofauna; 3) comprehensive monographs aimed at detailed description of freshwater mollusk species, including

D. polymorpha. The data provided in the publications of the two first categories served as primary data for analytic studies of the distribution of the species (e.g., [

70,

73]). In 1864, P. Fischer stated that the spread of the zebra mussel “in the waters of Central and Western Europe is one of the most curious facts in the geographical distribution of mollusks. Every day we witness new invasions of this mollusk, the successive stages of which can be carefully noted. When we encounter it in a certain [new] locality, it swarms there in such a way that its presence at a previous time could not have been passed over in silence” ([

73], p. 309). This conclusion coincides with those made by Fischer’s counterparts in England (see above).

The authors of large monographic works on the French malacofauna placed the zebra mussel in their volumes, bur either totally avoided discussion on its non-aboriginal origin in the country and the possible mechanisms of its dispersal [

74,

75] or only touched these subjects only in passing [

76]. For instance, Dupuy, having presented a lengthy description of the species’ morphology and the overview of its current distribution in France, added only that “the mussel was carried on the hulls of Volga boats to the Baltic Sea, and from the Baltic to England and in the rivers of Holland, Belgium, and France” ([

76], p. 661). A paper by Gassies [

77] provides a good example of a publication, documenting the arrival of

D. polymorpha in a new locality in France (Agen). Many short notes of this kind were scattered through the French scientific journals, primarily in

Journal de Conchyliologie which served as an important disseminator of such information. That of Gassies was unusual in that respect that the writer accompanied his record by a detailed overview of the previous taxonomic work on this mollusk and a lengthy discussion of the mechanisms of its invasion (adding, although, nothing new to the hypotheses of the preceding writers). Gassies, who believed that the marine and river navigation is the main vector of

Dreissena dispersal, attempted to imagine how the process of its naturalization begins. In his own words, “the boats, as they approach the quays or other boats, create a sort of friction which is enough to cause a certain number of

Dreissena to be released, which, as they soon lay their eggs, reproduce rapidly, especially considering the slow currents in the canals, where the locks keep the water in a state of stagnation which allows the animals to multiply extremely” ([

77], p. 23). Based on a presumed close affinity between the zebra mussels and the marine (edible) mussels, Gassies wondered if

Dreissena is suitable for humans’ food, and, seemingly, planned to make some experiments to know this: “We do not yet know whether experiments have been carried out to assess their edible qualities. We will wait until our specimens have reached a suitable size before subjecting them to the same culinary preparations as those used for

Mytilus edulis. Perhaps we will also try the condiments used in certain areas of the Agenais region to prepare

Anodonta and

Unio, without claiming to be introducing a new treat to the gourmet table” ([

77], p. 23). I do not know if the author were able to put this plan into practice, though Gassies reported he managed to establish a colony of

Dreissena in aquaria and, thus, he could conduct such a culinary experiment. His work contained a description of other observations, made in aquaria in order to study the movement and larval morphology of the zebra mussel ([

77], p. 24-25).

Another French naturalist of the late-19

th century deserves special consideration here. It is Arnould Locard (1841–1804), perhaps the only author of the studied period, attempting to put the discussion on invasive

Dreissena of Europe in an evolutionary context. In 1893, Locard published a lengthy monographic article aimed at taxonomic revision of the European dreisseniid bivalves [

70]. He stressed that the zebra mussel demonstrate huge conchological variability in diverse areas of its invasive range. In the opinion of Locard, this variability means that the “primitive type” of

Dreissena (i.e., that found by Pallas in the Volga and Ural rivers), after its infiltration to other basins of Europe, underwent dramatic phenotypic changes induced by the new living conditions. As Locard explained, “given such diversity in the appearance of the habitat, we will not be surprised to see that the primitive type, thus passing from one environment to another, did not always remain absolutely identical to itself. This resulted in considerable polymorphism, which is clearly evident when we compare series of Dreissensies of various origin. If certain colonies still preserve exactly the characteristics of the primitive type, others, on the contrary, present forms absolutely different from this normal type; and these are not simply individual modifications, because it is easy to see that these new beings group together according to their shape, just as easily as the first ones, that they are continually similar to each other, even in very distant colonies, and finally that they reproduce still similar to themselves” ([

70], p. 122). Locard did not hesitate to hypothesize that the naturalists are observing the gradual formation of new species of

Dreissena in diverse parts of Europe. As for his views on the essence of the species, Locard was an extreme nominalist in this regard. He belonged to the so-called “New school” of malacology see [

78,

79] for details, and, together with other members of this school, believed that the terms “species” and “variety” are utterly arbitrary, and the zoologists use them only for the sake of convenient classification. While most other malacologists of the epoch would treat these divergent forms of

D. polymorpha merely as intraspecific variations, Locard described them as full species and gave them binomial names. In his monograph, he recognized as many as 31 distinct species of

Dreissena in Europe and Asia Minor [

70], and these species were in many cases not allopatric (or vicariant) entities, equal to the “local races” of other systematists. Locard believed that several such ‘minor’ species can live in sympatry. For example, in a sample taken from the Elbe River near Hamburg he could distinguish not less than 4 ‘species’ [

Dreissena fluviatilis [=

D. polymorpha],

D. servaini,

D. sulcata, and

D. westerlundi); 9 species were found by him in the Paris City water supplies (

D. fluviatilis,

D. curta, D. tumida,

D. arnouldi,

D. occidentalis,

D. belgrandi,

D. recta,

D. lutetiana,

D. paradoxa). The mechanism(s) of the formation of these sympatric species were unclear to Locard (at least, he did not explain them in any way). Perhaps, he held the Lamarckian idea about the direct influence of the environment on the speciation, but Locard did cite neither Lamarck nor Neolamarckist biologists [

70]. On the other hand, he acknowledged that the change in conchological traits is not an obligate outcome of an invasion to a new locality. The “primitive type” remained unchanged in many regions of Europe, and shells collected from many invasive populations were indistinguishable from the zebra mussel of the Volga River [

70].

Subsequent authors did not follow the classification proposed by Locard. Neither Andrusov in 1897 ([

31], pp. 341-344) nor Skorikov in 1903 [

80] agreed to accept the numerous species erected by the French malacologist. Skorikov treated them as intraspecific morphs. Today, most of these species are considered junior synonyms of

D. polymorpha; and only a small fraction of species described by him from Asia Minor are accepted valid [

81].

Locard, however, discussed not only the classification of

Dreissena. He mentioned that the competitive abilities of the zebra mussel exceed these of the native species of the genera

Anodonta and

Unio (both belong to the freshwater family Unionidae) and, therefore, can potentially drive them from their habitats. Discussing the colonization of water supplies by

D. polymorpha, Locard emphasized that these mussels can play a positive role: being filter feeders, the mussels can serve to purify water. It would be useful if people could control the zebra mussel population by keeping its numbers at a moderate level [

70]. These remarks show that the author fully realized the ecological and economical consequences of the invasion.

I wish to add to this paragraph that

D. polymorpha quickly became a popular subject of anatomical and embryological studies in the French-speaking zoological community. Van Beneden, the Belgian zoologist, and the author of the generic name

Dreissena published detailed accounts on the external and internal morphology of the zebra mussel [

82,

83], which were later regarded as a classical morphological work on this subject. By the end of the 19

th century,

D. polymorpha was, probably, one of the best studied species of freshwater mollusks in this relation. Only a small fraction of original studies, published in various languages and devoted to anatomy, physiology, and embryonic development of this mussel can be mentioned here [

58,

84,

85,

86].

3.5. The European Naturalists’ Response to D. polymorpha Invasion: The German-Speaking Countries

The bibliography compiled by Limanova [

15,

16] shows that the German-speaking authors were the most prolific researchers of

Dreissena in Europe; the number of their publications on this species roughly 1.5 times exceeds the number of publications authored by English and French naturalists, combined. On the other hand, the response of German zoologists to the zebra mussel invasion followed the pattern described above, as exemplified by the English and French authors. The topics and genres represented in the German scientific literature were much the same as in other countries, which allows me to avoid a detailed review of the German publications, presenting instead a rather cursory summary of the most remarkable observations and opinions.

The earliest date of registration of

D. polymorpha in the territory of modern Germany was, in the 19

th century, a matter of debates. Though most researchers believed that the mussel was introduced to this area in the first third of the century, Mörch [

61,

62] attempted to prove that an obscure German conchologist (Sander, a gymnasium teacher in Carlsruhe) described this species as early as 1780. Martens [

72] strongly criticized Mörch’s opinion, arguing the Danish zoologist misunderstood the report of the 18

th century author. After all, added Martens, Mörch seemed to underrate the enthusiasm and zeal of German

Muschelsammler (shell collectors), who hardly could overlook this peculiar species had it been really living in the country around 1780. Stein ([

87], p. 106) witnessed that, near 1800, shells of

Dreissena were imported from Austria to Prussia, and the collectors paid up to 5 silver groschen for such rare specimens (most probably, these shells were brought from the lower Danube basin).

Martens himself dated the first arrival of this mussel in Germany to 1828 [

72]. (Wiegmann [

88] gave a slightly earlier date – 1827). In his opinion, in the Baltic countries

D. polymorpha was also a recent invader, not being presented there in the 18

th century. According to Martens’ detailed account, the mussel suddenly appeared in several regions of Germany between 1828 and 1835, which “caused a stir among naturalists themselves, but they calmed down again when they were convinced that von Bär had already found it in a freshwater bay and that it was not even a new species, but the old

Mytilus polymorphus Pall.” ([

72], p. 52). Karl von Baer [

36] noted that the mussel was living in the desalinated bays of the Baltic Sea and in the lower courses of the rivers, where it reached vast numbers. However, this biologist seemingly did not recognize

Dreissena as an invader in East Prussia. Only in 1837-1838, Wiegmann [

88] clearly indicated its non-indigenous origin in Germany and guessed that the zebra mussel might have arrived there either from Poland or directly from East Prussia. Another vector of

Dreissena dispersal discussed by this author was the river navigation from the west. Wiegmann cited a communication of someone Professor Kilian of Manheim, who witnessed that, in 1835,

Dreissena was found in high abundance on the keel of a ship arrived at Manheim from Rotterdam ([

88], p. 343). As it was stated many times,

Dreissena is virtually unable to migrate upstream without the help of human vehicles (or zoochory) e.g., [

80], and its passive dispersal from the Lower Rhine basin to Germany was improbable.

The large abundance of

D. polymorpha in East Prussia, reported by von Baer in 1825 [

36], may indicate that this species might have arrived there much earlier than the year of its first finding, which corresponds to the hypotheses of subsequent researchers [

2,

66].

The period 1827(8)–1835 coincided with the marked increase in the number of publications on

Dreissena in Europe, which took place in the 1830-s (see

Figure 1). The explanation for this sudden growth is that by the late-1830s the new mussel was detected in several European states (UK, The Netherlands, France, Belgium, Germany, Poland, the Baltic countries) and raised a vivid interest in the scientific communities of these countries (see above). However, by 1865, when Martens’ account [

72] was published, the zebra mussel managed to occupy only part of Germany; it was unknown from Bavaria and Swabia as well as from Switzerland. The first record of this species from the German part of the Danube basin (in Regensburg) is dated 1868 [

89]. (According to Jaeckel [

90], the first find of

D. polymorpha in Bamberg in Bavaria was made around 1861). Clessin assumed that the source of this introduction was the Rhine basin, not the Lower Danube.

Dreissena used a canal connecting the Rhine and Main rivers and reached Regensburg through the Main-Danube canal [

89]. In Austro-Hungary, this bivalve remained very rare and locally distributed even in the late 1880s [

91,

92,

93]. For instance,

Dreissena was unknown in the Danube River between Vilshoven in Bavaria and Budapest; Lampert [

93] explained the findings of the mussel in the latter city by its transport with ships from the lower courses of the Danube, not by its passive dispersal downstream from the territory of Germany. Lampert stressed the fact that shells of

Dreissena are known from the Pleistocene deposits of Northern Germany. Thus, this species is not truly “alien” to the country; it merely restores its lost range in Central Europe ([

93], p. 80-81).

It seems that the ecological peculiarities of

D. polymorpha, especially its biotic interactions with other organisms of the biocoenoses, were a subject that German naturalists were a little more interested in than their colleagues in the UK, France, and Russia. The German literature of the discussed period is fulfilled with such observations, directly relating to the invasion ecology of the zebra mussel, including its movement and mechanisms of migration. Numerous observational notes of this kind appeared in the German popular scientific periodicals such as

Aus der Heimat (From the Homeland),

Der Zoologische Garten (The Zoo),

Blätter für Aquarien- und Terrarien-Kunde (A Leaflet of Aquarium and Terrarium Science), etc. Struck [

94,

95] observed that

D. polymorpha may use the bodies of motile animals (river crayfish) as a substratum for their settlement; this can represent a means of the zoochoric dispersal of the mollusk. The same author published a brief list of freshwater fish feeding on

Dreissena in Germany [

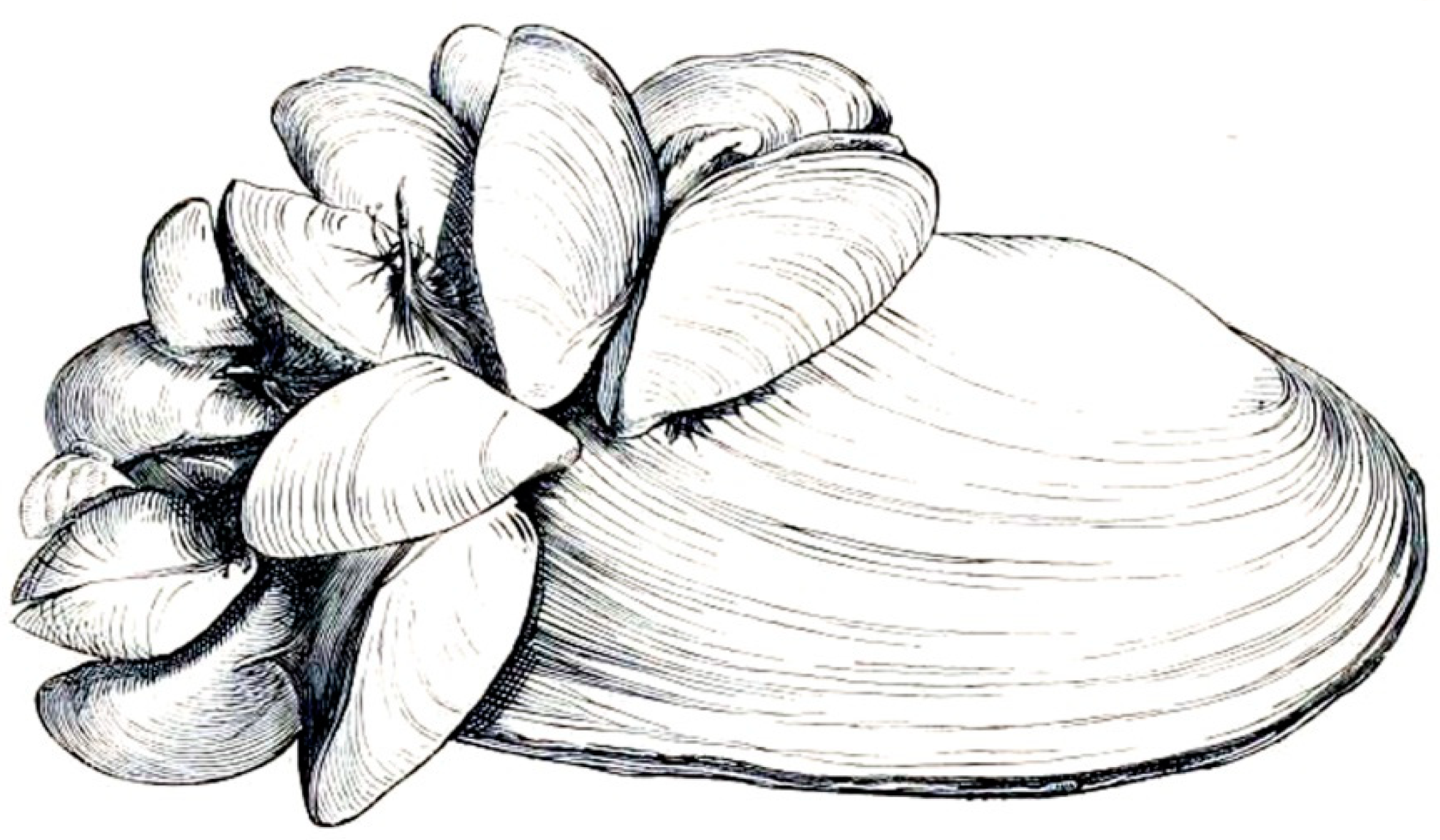

95]. The interactions between the zebra mussel and the native species of large unionid mussels were also a subject of observation and illustration (

Figure 4). Frenzel [

96] determined the suite of aquatic organisms associated with colonies of

Dreissena; it includes larvae of various insects, the water louse, gammarids as well as leeches and diatom algae (Bacillariaceae).

The same author described the slow movement of the juvenile mollusks by ejecting water from the outlet siphon and the simultaneous closure of the shell valves with a sharp contraction of the closing muscles. Alternatively, the mussel may use its foot to move. Frenzel also observed the migration of small colonies of

Dreissena with the onset of winter from shallow areas to deeper places of a waterbody [

96]. This also happens in cases where the substrate on which the zebra mussel colony is located (e.g., a submerged stone) is displaced or turned upside down, and the mollusks tend to return to their original position [

96]. It turned out that the adult mollusks are able to break off their byssal thread and move along the substrate in search of a new attachment site. The observations made by Frenzel were confirmed by other authors, worked in the next century [

98,

99].

Germany became, perhaps, the first European country where the disappearance of

Dreissena from once inhabited rivers due to water pollution was observed. In 1897, Friedel quoted after [

57] showed this happened in the Spree River, where the zebra mussel was living since the 1850s.