1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Ethiopia has a small number of researchers (45 per million inhabitants), less than half the African average (Fosci et al., 2019). More than half of Ethiopian researchers (56%) work for the government, while the remaining researchers (44%) are employed by higher education institutions (Fosci, Loffreda, Chamberlain, & Naidoo, 2019; Njuguna & Itegi, 2014). The Ministry of Education has designated Ethiopia's first-generation universities as research-intensive universities, shouldering research project production, dissemination, utilization responsibilities, and accountability for desired and undesired research outcomes (MoSHE, 2020; EGHEP No. 650/2009). Bearing such research-intensive responsibilities in mind, Ethiopian universities and academics in their respective universities had conducted several research projects and published articles within indexed journals, although they were not sufficient for addressing and achieving sustainable holistic development of the nation. They provided research-based solutions for problems, although no one (the government, institutions, or individuals) adequately used the majority of them to solve the intended problem except keeping them on the office shelf or in the library. Moreover, how much such research outputs were sufficient compared with expectations and local to global average performances in the Ethiopian nation, institutions, or globally did not get attention and lacked investigation by Ethiopian researchers with Ethiopian context?

In line with this, Ethiopia’s Draft Education Development Roadmap for 2030, MoE (2018), acknowledges that research achievement is far below the country’s aspirations due to poor oversight of research applicability, a scarcity of knowledge frontiers, and a limited number of personnel available to conduct high-quality and relevant research in the country’s HEIs. This document highlights the status of Ethiopian research productivity, although it is not a formal scientific research output conducted following scientific procedures that triggers researchers to conduct scientific research on this topic.

In addition, even the first-generation research-intensive African or Ethiopian universities’ and academics’ research participation, production, and dissemination capacities remained uninvestigated to determine their status compared with the national, African, and international research production and dissemination standards or cutoff points in the form of ratio of individual academics to research projects conducted per year, ratio of academics to indexed research publications, h-index, and citation index metrics (Fosci et al., 2019; Quimbo & Sulabo, 2014). Ethiopian research institutions and its’ universities were not well represented in the sample of many African and global research productivity studies, including the previously determined research productivity standards or parameters. For example, the average h-index of African universities is 11.38, while the global average is 17.5. Ethiopian universities' average h-index is 7.58. Likewise, the average citation index worldwide is 971, Africa is 722.49, and Ethiopia is 478 (Kpolovie & Dorgu, 2019). Kpolovie and Dorgu (2019) investigated generally African research productivity, representing Ethiopia only by involving Addis-Ababa University as part of their study sample, which showed sampling limitations.

Therefore, this study addressed these research gaps and aimed to determine the status of research productivity (research project production, indexed article publication, and conference paper presentations) and the causes behind these research productivity statuses in Ethiopian Amhara Regional State first- and second-generation public universities.

1.2. Research Problem

In the global world, universities are expected to conduct adequate scientific research projects with resulting new knowledge and creativity that enable the surrounding community or the nation to transform towards psycho-social, political, economic, educational, and service delivery developments (Tekeste, 1990; Tekeste, 1996; MoE, 2018).

Scholars in developed countries took the lion's share of conducting the majority of global researches with adequate dissemination and utilization cultures, Demeter, Jele & Major, (2022), while developing countries conducted minimal research projects with inadequate dissemination and utilization cultures until recent decades and the present time (Mathies, Kivisto, & Birnbaum, 2019; Abramo et al., 2011; Quimbo & Sulabo, 2014).

For instance, Fosci et al (2019) wrote a research report entitled “Assessing the needs of the research system in Ethiopia: a report for the SRIA Program” which was investigated applying both quantitative and qualitative analysis using desk-based data from 16 sources (reports, articles, websites, databases…) and 4 key informant interviewees under 100 research indicators to investigate Ethiopian research system while our study was conducted at higher education institutional, college and individual level of analysis employing mixed method research design with the questionnaire and interview data to investigate the status of research productivity in universities and the factors behind the identified statuses.

Fosci et al. (2019) stated in their findings and conclusions that the Ethiopian research system lacks capacity and is characterized by severe scarcity of funds. Similarly, the researchers in the current study aimed at identifying more detail reasons for the low volume and status of research productivity such as a weak research culture, weak leadership behavior practice, and political instability at regional and national levels felt as additional major factors in Ethiopian Amhara Regional State Public Universities (EARSPU).

Likewise, Kplove and Dorgu (2019) investigated African university faculty’s research productivity using h-index and citation index measures searched from the Google Scholar database. They draw 3000 faculties (200 each from the selected universities) whose h-index and citation index are drawn under 15 universities grouped into the 5 regions of Africa for which they are used for comparison purposes. Addis Ababa University was the only university representing Ethiopia. Southern Africa was represented by the University of Pretoria in South Africa, and Northern Africa was represented by the University of Cairo in Egypt, both of which demonstrated above-average African and world-average research productivity performance cut-off points, while the remaining African regions were significantly below the above cut-off points. Although the current study also investigated the universities’ and academics’ research productivity status, it differed in design, setting, and the nature of the data used from the above study, which filled in some of the gaps observed from the previous similar studies:

In general, there are some research studies in the literature conducted to investigate the state of research productivity in Ethiopian universities (Wubalem & Serangi, 2019; Amare, 2000; Dufera, 2004; Redley, 2011) and the factors behind the status in the Ethiopian university context (Tesfaye, 2011) and in the global university context (Pring, 2001; Stupnisky et al., 2022; Egar & Geare, 2013; Brew, Boud, Namgung, Lucas & Crawford, 2015; Quimbo & Sulabo, 2014). The current research was conducted differently, at least in one dimension or more (e.g., design, setting, level of analysis, type of data, identifying causes for the identified statuses etc.), from all of the previous studies in the literature.

Therefore, the investigators of the current research were motivated to identify the current status of research productivity in Ethiopian universities, including the major causes of the identified status, using different samples, settings, methodologies, and findings from the previous studies conducted.

To guide this study, the following null hypothesis was tested at 0.05 alphas significance in phase I and one research question in phase II:

Phase two RQs

1.3. Significance of the Study

The findings of this study provide an insight for HEI policymakers and leaders about the volume and quality statuses of the universities’ and academics’ research productivity against institutional, national and global standards and the reasons for the identified statuses. The study also provides an insight for academics themselves about their volume and quality status of research productivity so that motivate and adjust themselves for the next academic years. Furthermore it provides an insight on how to apply the RBVT and SDT for improving research productivity of academics.

1.4. Scope of the Study

This study was delimited to the volume and quality statuses of academics’ research productivity and the reasons behind the identified statuses in three universities of Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. In terms of time span, it was also delimited to 2017 to 2022 academic years. This study was also delimited to first- and second -generation universities and their academics for both undergraduate and postgraduate programs.

2. Theories Supported the Current Study

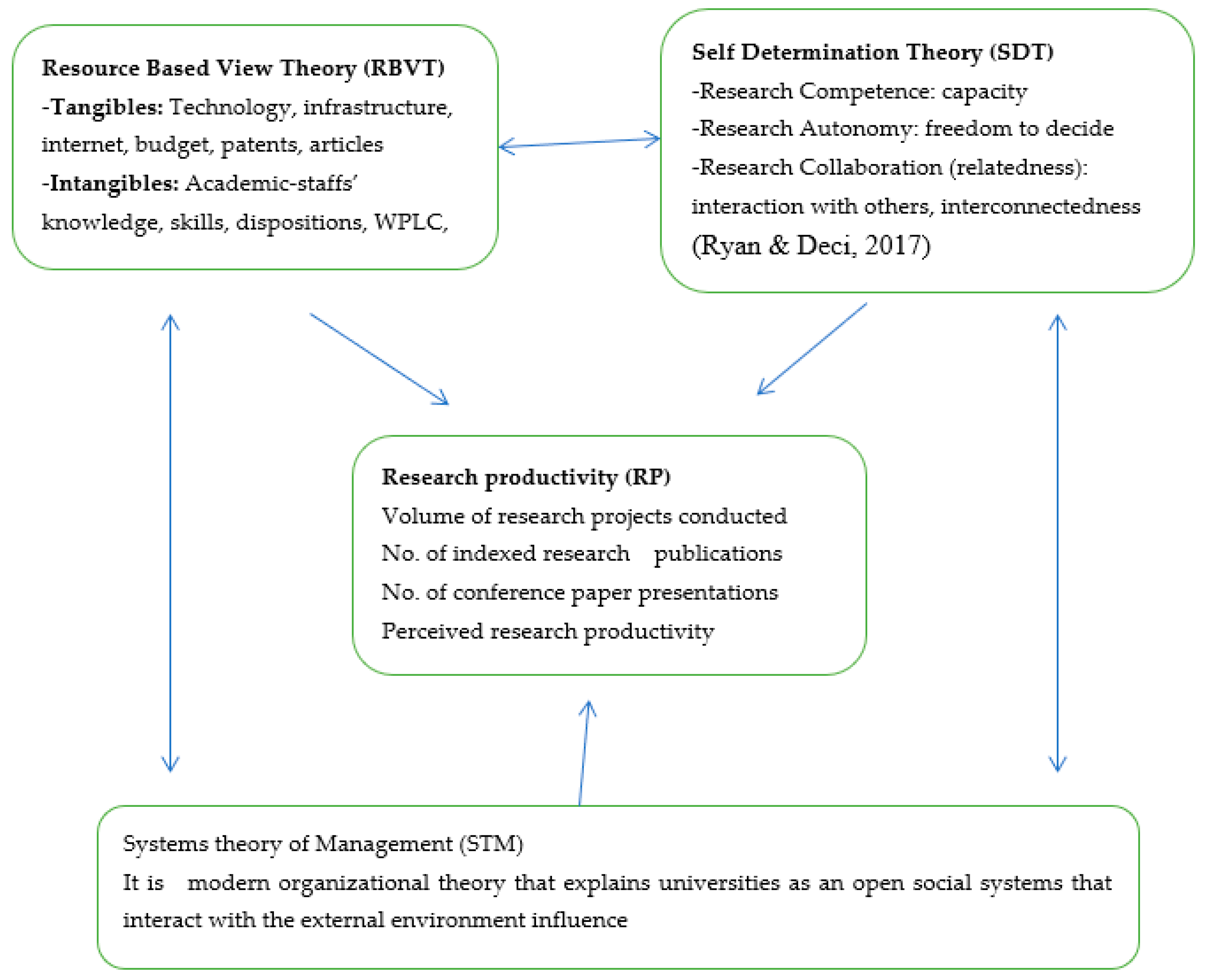

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) with in the umbrella of Resource Based view Theory(RBVT) suggests that universities’ and academic staffs’ research motivation and productivity is largely influenced by the fulfillment of three fundamental requirements: competence (perceived research expertise or skill), autonomy (freedom to choose research initiatives and strategies; freedom to investigate truth and facts), and relatedness (feeling connected with collaborators: deans, presidents, MoE, industries, partners, surrounding communities, etc.). SDT states that the type of motivation, driven by satisfaction of the above basic psychological needs, is critical to predicting academics’ research outcomes (No, of conducted research projects, indexed publications, conference presentations, citations, h-index) in the context of academics’ research productivity (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Research productivity is also defined as the ratio of research inputs (the researchers’ and collaborators’ knowledge, skill, and value (human capital), technology, infrastructure, funding, priorities, the way organized, stakeholders’ interrelatedness, etc.) to innovative research outputs (new technologies, patents, ideas, solutions to problems (societal effects), publications, citations and h-indexes). This concept of research productivity is also supported by resource based view theory.

Generally speaking, the objective of research project production is to produce new knowledge. Research productivity is a production process in which the inputs consist of human, tangible (scientific instruments, materials, etc.) and intangible (accumulated knowledge, social networks, economic rents, etc.) resources, and where output,( the new knowledge), has a complex character of both tangible nature (publications, patents, conference presentations, databases, etc.) and intangible nature (tacit knowledge, consulting activity, etc.). The new knowledge production function has therefore a multi-input and multi-output character. The principal efficiency indicator of any production unit (individual, research group, department, institution, field, country) is productivity: in simple terms the output produced in a given period per unit of production factors used to produce it. To calculate research productivity, one needs adopt a few simplifications and assumptions (Abramo & D’Angelo, 2014).

Furthermore, because the intensity of publications varies across fields (Garfield 1979; Moed et al. 1985; Butler 2007), in order to avoid distortions in productivity rankings (Abramo et al. 2008), one should compare researchers within the same field. A prerequisite of any productivity assessment free of distortions is then a classification of each individual researcher in one and only one field. An immediate corollary is that the productivity of units that are heterogeneous for fields of research of their staff cannot be directly measured at the aggregate level and that there must be a two-step procedure: first measuring the productivity of the individual researchers in their field, and then appropriately aggregating this data.

The diagrams below illustrate the theoretical basis for this study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Basis of the Study.

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical foundations that this study’s criterion and the causal factors originated from assumptions rooted in the interactions of RBVT, SDT and STM with in university contexts.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Basis of the Study.

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical foundations that this study’s criterion and the causal factors originated from assumptions rooted in the interactions of RBVT, SDT and STM with in university contexts.

3. Methods

In this study, assuming the merits that relatively underpin the philosophical positions of both the post-positivist and the constructivist paradigms, mixed methods research design specifically the explanatory sequential design which focused on first the significance tests and then the qualitative part were analyzed and discussed. For quantitative or objective reality analysis of data, a survey research design was used, while a case-study design was employed for the qualitative part. The researcher selected first- and second-generation universities in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia, as the total population for this study. Such sampled universities specifically represent first and second generation universities in Amhara regional state and are generally representative of Ethiopia's first and second generation universities due to many similarities, such as the fact that all are government universities subject to government policy, rule, budget, staff, and so on.

We used a random sampling technique to select the three universities, such as Bahir Dar University (BDU), the University of Gondar (UoG), and Debre-Markos University (DMU), from the five available universities found in the Amhara regional state. We initially limited the first and second generation universities in the Amhara regional state due to budget scarcity, regional ethnic based conflict that created insecurity, and to make the study manageable in several respects. From the total population of 1973 academics in the three sampled universities, 550 participants were selected to fill in questionnaire items, although the final number was reduced to 519 participants due to the fact that 31 questionnaires were dropped during data encoding processes because of the existence of incomplete and error cases.

In part one of the questionnaires, the participants filled in background information items including: The number of research projects conducted by the participant; The number of articles published in non-predatory journals and The number of conference presentations undertaken in the last five years (from 2017 to 2021).

In part two, participants completed continuous data variables (perceived research productivity) items using six option scale of 1= strongly disagree to 6= strongly agree.

Then, analysis was carried out using one sample t-test and the findings were organized, analyzed, and discussed in a meaningful pattern so as to reach the conclusions and suggestions. Likewise, the researcher used cross-tab descriptive analysis to delve into the states of research and publication development trends in Ethiopian universities. In addition, the researchers used thematic evidence organizations to consolidate empirical evidence that supports the quantitative analysis.

Interview findings (13 interviewees) were also used to analyze research question five using the following themes: academics research perception, research capacity, research fund, research culture, institutional leadership influence and external environment influence, which were identified in the interview transcript protocol of this research study.

4. Results: Phase I: Quantitative Analysis

4.1. Research Productivity Sub-Constructs Volume and Quality Statuses

Table 1 shows the mean comparisons between the actual mean and the cut-off point test values. As demonstrated in

Table 1, all the three universities revealed a statistically significant mean difference, which is far below the cut-off values, that is, 5 research projects, indexed journal articles, and conference paper presentations for the last 5 years (from 2017 to 2021). Academic staffs are expected to conduct at least one research project, produce one indexed journal article, and conduct more than one conference paper presentation per year and five articles for five years (from 2017-2021). This cut-off point is based on the institutional and ministerial threshold directions highlighted for research-intensive universities in Ethiopia, (BDU, 2019).

Furthermore, this value was also lag behind when compared with African and international research productivity average performance parameters including the citation index, h-index and ratio of academic staff to indexed publication, research project conducted and conference paper presentations per year.

Phase II: Qualitative Analysis

After completing the quantitative hypothesis test analysis, the researchers were able to explore the reasons behind the identified volume and quality of research productivity statuses using qualitative data. The qualitative analysis began with describing interviewee personal demographics and other details in the interview transcript protocol and coding processes.

4.2. Exploring the Causal Factors for the Obtained Status of Academics’ Research Productivity

RQ1: What are the factors behind the obtained volume and quality statuses of research productivity in the respective college for the last 5 years?

After developing interview transcript protocol for each interviewee based on each semi-structured interview items, we identified the most frequently uttered causes for academics’ low research productivity status and formed a group of themes to be involved in the analysis to answer RQ1. To this end, the interview findings were organized under six major themes such as academics perception to research; research culture; research fund, academics’ research capacity, productive institutional leadership and external environment influence.

4.2.1. Academics’ Perception to Research

Interviewees generally expressed that Perception of academic staffs about the utility of research was increasing for the last five years. Several academics in their respective colleges conducted mega or individual research project proposals and submitted them to their respective colleges so as to compete for a research grant. In support of these evidences one of the 13 interviewees, Azmeraw opined “ …I believe that conducting research project which leads to indexed publication is my career responsibility. I need to engage in more self-efficacy, effort, commitment and time devotion …for research in the next academic life” (18 April, 2022:0:45). Likewise, Ahmed expressed his perception towards research saying “I feel good for conducting research projects in my college since the research grants and publication incentives are moderately satisfying for me” (17 April 2022, 0:50). Moreover, Ewnetu, uttered his feeling to research productivity: “I am happy for the volume of research projects I conducted and the number of publications I made in my career life” (3 June 2022, 0:55. These evidences generally implied that academics’ perception to research productivity was positive and relatively good compared to the previous academics’ research perception and engagement in Ethiopian universities.

4.2.2. Research Culture

Several interview participants developed a common understanding on their research culture. In many Ethiopian universities, the processes of research proposal evaluations and research project production did not follow genuine research evaluation & monitoring standards although general policies for research exist. In each academic year considerable number of researchers submitted their research proposals to their respective college for research grant request but proposal evaluations and selection decisions were not done based on the quality of the research proposal rather based on other than the quality of the proposal that is friendliness, revenge, sabotages, securing personal privileges etc. These realities in turn threatened academics’ trust, commitment, dedication, and belief on research participation and the quality of research project production. In support of these research trends, Habtu who is an interview participant claim saying “…Even some academics and committee members who are assigned to review research proposals consider retaliation and personal privileges into account which seriously affect the quality of judging the research proposal” (9 April, 2022, 1:10). In addition, another interview participant (Medihanit) also confirmed the dominance of such research culture opining this event “ in my university experience, I often observed several interpersonal or intergroup conflicts at the time of research proposal reviewing, evaluation and selection decisions that adversely affect the respective colleges research culture” (3 June, 2022, 0:50).

Sewlesew Misikir was also one of the 13 interview participants who witnessed the research culture of his college a little bit different from the above two informants and partially supporting this analysis saying “Our college research proposal evaluations and selection decisions were carried out with relatively fair processes and selection judgments that partially satisfying majority of us (research proposal applicants)”. These evidences imply that such relatively fair proposal selections contribute for improving researchers’ perception, commitment, and trust towards their research self-efficacy and the leaders in their college. To sum up this theme analysis, universities and their respective college academics emerged relatively weak research culture which hindered desired research productivity of universities unless such universities improved their research culture.

4.2.3. Research Fund

The researchers from their experience have identified research fund scarcity, especially internal fund scarcity, is a serious problem for Ethiopian universities including BDU, UoG & DMU. We found that Ethiopian universities have large limitations of accessing research technology such as internet, recorders, laptops … and infrastructure which are suitable for research. In support of this Tenamedihin Adane stated scarcity of research fund saying “…scarcity of research fund is one of the main two or three obstacles for academics to conduct research in my college and university” (3 June, 2022, 0.50). Likewise, Mizanu expressed the lack of research fund saying “unless the government and the university able to allocate research budget, academics did not conduct research project covering the financial cost due to their limited financial capacity”(13 April, 2022, 0: 45). As a result, the number of research projects conducted by academics in Ethiopian universities fell below expectations; even some academics with many years of experience did not conduct one research project in their university work life as indicated in the quantitative analysis.

From resource based theory point of view, these findings generally imply that research fund scarcity appeared in all colleges that the university and college officials did not allocate adequate budget for research productivity may be due to they give less attention and priority for research productivity or they misused the allocated budget for other ordinary duties. These fund limitations also cause the colleges unable to fulfill the academics’ basic psychological needs of self-determination theory such as research competence development via budget supported trainings, building research collaboration and partnership support, and the colleges’ autonomy or freedom of making finance oriented research decisions in their respective college.

4.2.4. Institutional and Academics’ Research Capacity

A considerable number of academics have come across shortage of research knowledge, skill and collaboration in their day to day research activities in their universities. There were not delivered sufficient research trainings which can improve the research abilities of academics almost in all colleges of the universities. These evidences imply that one of the SDT psychological basic needs of academics that are research competences is unsatisfactory. In support of this, one of the interview participants, FitretAlem Amanuael said “ I did not get sufficient research trainings that result in adequate research knowledge and skill so that I feel low research self-efficacy and became poor in research productivity(19 June 2022, 0:52).

4.2.5. Institutional Leadership

It is true that leadership of any type (democratic, transformational, transactional, autocratic, destructive leadership …) substantially positively or negatively affected the academics’ and institutions’ research productivity. Generally interviewee participants disclosed transactional leadership (rewards and punishment based leadership) with traditional low practice of justice, less collectively shared culture and low workplace learning capability as the dominant leadership behavior and the contingent contexts practiced in their respective college and university.

From the SDT perspective, this implies the presence of lower autonomy and freedom in the Ethiopian higher education system that leads to lower academics’ research productivity. In support of this, interview participant Mizanu B. witnessed “I observed that there were unstable deans’ leadership behavior which were unresponsive to both the academics’ and the university’s needs. Because of these weaknesses considerable number of academics distrusted their deans and institutions that they less likely secured their research productivity in terms of grant provision, research proposal evaluation, incentives and research capacity buildings” (3 June, 2022, 0.50). From this evidence we can understand that the academics’ interrelatedness with their deans became distrustful which reduced research collaboration in the collage. Therefore, these colleges did not adequately fulfill the third psychological basic need (relatedness) of academics in SDT which is essential for achieving desired research productivity.

In addition, their colleges often accompanied with internal or external harmful conflicts that indicated leadership inefficiency to make conducive workplace relationship so that enhance research productivity functions. Hence, the assumptions of both RBVT and SDT were no fulfilled for academics and the university leaders considerably violated these assumptions.

Likewise, networked college culture with reciprocal relationship dominated the deans’ leadership behaviors that imply leadership inefficiency from RBVT and SDT point of view.

5. Discussion

This section involved integrated arguments among the findings, empirical evidences and theoretical frameworks under two subheadings.

5.1. The Status of Research Productivity in Ethiopian Amhara Regional State Universities (EARSU)

Research project production, dissemination, and utilizing it for solving the day-to-day as well as strategic performance problems and conceiving change initiatives of individual, institutional, and national businesses or interests is a required precondition for the nation’s holistic development and advancement(MoE,2018; Altintas & Kutlu, 2021). Universities take the largest share of research project production and dissemination in developed countries, Demeter et al (2022) although the practice is minimal for developing nations in Africa or elsewhere (Fosci et al, 2019; Teferra & Greijnaver, 2010; Gordon, 2014; Kpolovie & Dorgu, 2019; Njuguna & Itegi, 2013 Boateng, 2020; Deuren et al., 2015).

As indicated in

Table 1, the one sample t-test result confirmed that the status of academics research project production, indexed journal article publication and conference paper presentation performances were statistically significant below the desired average performance cut-off points or local, national, and international average performances that get support from previous studies (Fosci et al, 2019; Caminiti et al, 2015; Quimbo, & Sulabo, 2014). However, scholars argue that the industrialization of a nation or continent is dependent on the prowess of universities' ability to take the lead in the processes of knowledge discovery (Kpolovie & Dorgu, 2019; Fosci et al, 2019). Universities are saddled with the responsibility of discovering new ideas and modifying old ones to soothe the changing trends of life, (Altıntaş & Kutlu, 2021). Universities are considered modern entrepreneur engines and generators of knowledge through research (Kpolovie & Dorgu, 2019).This finding can be also discussed from the assumptions of resource based view theory (RBVT) that the actual volume of resources used and outputs gained differ from the planned or desired standard which imply inefficiency in resource utilization, inefficiency in the system of research project production, and publication, which leads to lower actual outcome than the planned outcome (Barney, 2001).

5.2. The Major Factors behind the Observed Research Productivity Status in EARSUs

As indicated in

Table 1, the status of RP (volume of research projects conducted, indexed publications and academics conference presentations) was significantly below local expectations, national, African and global average thresholds. There were several factors for this low status. In general based on the findings from interview transcript protocol, researchers identified six major themes such as academics’ perception, lack of capacity, weak research culture, lack of research fund, lack of productive institutional leadership and the external environment influence.

5.2.1. Academics’ Research Perception

Academics research perception of the utility of research productivity is vital. It is a requirement for academics’ promotion and their job advancement, filling personal competence gaps, institutional growth and nationwide developments were relatively growing up as indicated in the interview report of interviewees and it was supported by empirical evidences, (Ankerlin, 2008;Horta & Santos, 2019 Fosc et al, 2019). Similarly, Fosci et al, (2019) stated that research productivity perception of African universities’ academics including Ethiopia was increasing in the recent decades due to relative improvements in budget, research considerations by academics, and accountability. Even though, the number of research projects conducted, indexed publications and conference presentations of academics in each university and respective colleges did not satisfy the average institutional, national or global average performance thresholds in terms of academics to research project production ratios, academics to indexed publication ratios, h-indexes and citation indexes as indicated in quantitative findings of this study and interview findings.

Academics’ perception of clear performance expectations, such as well-defined targets for research, conference presentations, publications, and grant applications, have also been found to contribute to research success. For instance, O’Meara et al. (2016) similarly found “unmet expectations and broken contracts shaped the departure decisions” (p. 291) of considerable academics who had committed to research productivity their institutions, (Stupnisky et al. 2022).

Generally, academics motivation to conduct research is relatively increasing although their research competence and autonomy declined due to lack of adequate training, traditional leaders and politics interferences.

5.2.2. Academics’ Research Capacity

Generally academics research competence including their research knowledge, skills and dispositions were insufficient that caused low research productivity in Ethiopian Amhara Regional State research intensive universities, (Fosci et al, 2019, Caminiti et al, 2015).Research capacity building trainings were not delivered regularly at least biannually or yearly except occasionally delivered for the academic staff in their respective colleges. From these discussion points, we can argue that these universities and their academics did not satisfy one of the basic psychological needs of SDT (research competence) which are very important for the academics’ research productivity in ARSU.

In addition, there are also shortages of well-trained and well-organized research training centers with certified trainers who are familiar with a desired analysis tools for both the quantitative and qualitative research approaches in each universities even in the research-intensive first-generation universities of Ethiopia (Redley, 2011, Fosci et al, 2019).

Basically, academic-staffs working in Ethiopian universities are expected to have adequate competencies in the following research competence domains: research instruction, research production, interpersonal relations or collaborative skills, research knowledge, and overall skills, together with desired research dispositions (values, Beliefs, attitudes etc.), (Pring, 2001; Fosci etal, 2019; Ridley, 2011; Amare, 2007; Stupnisky; Larivière; Hall & Omojiba, 2022, Kerebih et al, 2020). However, many academics working in Ethiopian universities became insufficient with all the three necessities, such as research knowledge, skills, and the desired research culture, as observed in the quality audit reports, research work performance reports, and self-evaluation study reports (HERQA, 2008).

From these discussions also understand that the three dimensions of SDT (research competence, autonomy and relatedness) basic psychological needs were not fulfilled for academics with in these universities. In support of this, Fosci et al, (2019) stated that overall research training capacity in Ethiopia was very low, local availability of research specialized training services was below average, and funding for research capacity strengthening was poor which were in line with this study findings.

Specifically, in the university setting, college deans in their respective universities are responsible and accountable for academics’ research capacity building together with the willingness and effort of individual or group of academics via providing research skill training, formal classroom instruction, organizing conference presentations, delivering periodic academic forums (FDRE, 2009; Jensen, Vera & Crossan, 2009; Vera & Crossan, 2004).

5.2.3. Academics and Institutional Research Culture

The colleges’ research culture needs fundamental reform in terms of building academics’ research competence, genuinely reviewing manuscripts, securing a research grant for deserving research proposal, conducting the research proposal as per the quality standards, publishing research projects in indexed journals and utilization of research products for solving our problems and to support innovation and genuinely utilize research findings for fulfilling gaps or solving problems, and reinforce its long-term orientation to meet the needs of Ethiopian societies (Redley,2011;Fosci et al 2019; Quimbo & Sulabo 2014). As reported in the interview responses, the research culture of the four colleges in their respective universities characterized by relatively weak research cultures those need strong effort of both academics and leaders in each university to create strong, competitive, collaborative, problem-solving and innovative research cultures (Wubalem & Sarangi, 2019; Mathies, Kivisto, & Birnbaum, 2019). The research culture reform shall consider the SDT including the three basic psychological needs of research competence, autonomy and collaboration as well as the RBVT in terms of efficient research resource utilization to maximize research output as a guide.

5.2.4. Research Fund

Academics often attributed their research productivity problem mainly to poor funding of individual, institutional and external donors. The financial capacity of individual academic staffs are not capable to cover financial costs of research project proposal preparation, carrying out the research proposals, publishing manuscripts in indexed journals and disseminating the new findings to desired audiences via conferences and preparing research project findings for community service deliveries, (Fosci et al, 2019; Uwizeye et al, 2021; Pring, 2001).

Currently Ethiopian universities involved some career positions with in the university’s organizational structure and allocated budget for research purpose. Even though, the amount of this budget is not sufficient to provide grant for majority of research proposals submitted by academics so as to get a grant. Academics also encountered lack of budget for reviewing manuscripts and publication fees although relatively moderate publication incentives were offered for only WOS, Scopus and PubMed indexed as well as accredited domestic publications by some universities in Ethiopia (Mathies, Kivisto & Birnbaum, 2019; Aagaard, & Schneider, (2017).

These performance-based research incentives in Ethiopian universities may be a cause for accumulation of majority research project production and publications by few or a few academics in their respective colleges and universities (Mathies, Kivisto & Birnbaum, 2019; Quimbo & Sulabo 2014, Stupnisky et al, 2022).

In addition, the assumptions of RBVT that is the synergy of inevitable scarcity of resource supply and efficient utilization for maximal output as well as SDT principles of research fund generating and utilization capacity, autonomy and collaboration are essential for funding reforms in general.

5.2.5. Institutional Productive Leadership

The research productivity of academics in the respective colleges was substantially influenced by the deans’ leadership behavior in each college and university (Horta & Santos, 2019). For instance, creating conducive work environment of both internal and external relationships with fairness and democracy characterize productive deans’ leadership behavior. However, lack of productive deans’ leadership including unstable institutional climate, injustice in treating academics and making decisions, un-participatory and biased research work evaluations and lack of directing the college in relation to external socio-political environment with so much interpersonal and group or intergroup conflicts within each university and in the nation at large were the determinant factors for the low research productivity of universities (Li & Zhang, 2022). For instance, Amhara regional state as one of the country’s provinces accompanied with many ethnic and political based wars in addition to COVID 19 pandemic during the time period of this research project development and final performance from 2017-2023 (Ibreck & Alex, 2022). These evidences inferred that academics research productivity was not adequately supported by the fulfillment of the basic psychological needs of academics from the point of SDT.

5.2.6. The External Environment Influence of the Respective Colleges

The respective colleges in ARSUs are accompanied with several personal or institutional collaborations and partnerships with in the institution (the presidents, directorates and other colleges) or abroad (MoE, regional and federal council political elites, the community, international research centers, journals and so on) which can be viewed from relatedness dimension of SDT. All of these relationships influence the colleges’ research productivity positively if they became opportunities and or negatively if they became threats for the colleges’ research productivity.

In addition, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) were also severely affected by the national and regional political instability in Ethiopia during the recent decades, especially (2017 to 2023) in several respects such as: 1) HEIs received low financial budget from the government. 2) HEIs were unable to create more and more global partnerships to receive global research fund from various donors. 3) HEI academics were unable to conduct research project and related activities in HEIs within the country due to security problems. 4) HEIs lost their trust by its staff and the nation’s ethnic groups (Ibreck & Alex, 2022; Kumilachew et al, 2021). Therefore, the researchers argue that the Ethiopian HEI’s external environments were one of the determinant factors for the individual academics and institutional research productivity (Li & Zhang, 2022; Stupnisky et al., 2019a). From this discussion, we suggested that the second and third dimensions of SDT that are relatedness, autonomy and freedom of research decisions by academics were inadequately practiced in these universities.

6. Conclusion and Recommendation

6.1. Conclusions

The magnitude of research products and publications produced in Ethiopian universities were substantially lower than African and world averages as average mean comparisons demonstrated in the presented data. And even the actual mean is lower than the expected mean or cut value set by the researcher. Moreover, this study found six major fundamental thematic areas (academics’ perception, lack of capacity, weak research culture, lack of research fund, lack of productive institutional leadership and the external environment influence) that threatened the research productivity to be lower than local and global average performances or parameters. For instance, academics to research outputs ratios, No. of research projects conducted per year, No. of non-predatory journal articles published per year, citation indexes, h-indexes, etc.).

When viewed from SDT dimensions, the academics’ basic psychological needs of research productivity such as research competence, research collaboration and autonomy or freedom to research decisions were not adequately satisfied as discussed in the reasons for the identified low volume and quality statuses of research productivity.

6.2. Recommendations

Resource Based View Theory (RBVT) of research production efficiency and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) basic psychological needs of academics for better research productivity such as research competence, relatedness or collaboration, autonomy and freedom are essential requirements. Therefore, universities and MoE need to fulfill and practice such necessities for research productivity.

Academics’ research production, dissemination and utilization skill is insufficient for majority of them that without improving such skills, colleges and their respective university are unable to advance its research production, dissemination and utilization performance up to the desired institutional, national, African and world average cut-off-points or standards. Therefore advanced research trainings for academics that focus on capacity building is essential. MoE, university presidents and Deans of the respective colleges in-collaboration are more responsible and accountable for doing it.

The college deans in their respective university shall establish the desired research culture involving fairness, equality, equity … with research proposal reviewing standards and criterion free from objection by academics. For setting such research proposal reviewing and evaluation criterion and determining the final selection decision of the deserved proposal shall be carried-out with participation of academics.

Budget scarcity is common for all colleges in each university and utilizing it unwisely and unfairly without addressing equality and equity issues causes the problem to be worse. These events caused the low performance of academics’ research project participation, research production and publication performance development. So, clear mega or individual research proposal reviewing and evaluation criteria or standards shall be designed and practiced to eliminate conflicts, complains…of academics during research proposal selection for a grant.

Each university colleges’ research project production, publication and utilization performance development shall be viewed considering world, continental, national and institutional average performance cut-off-points including: ratios of academics to research project outputs, ratios of academics to publication per year, ratios of academics to conference paper presentations, h-index and citation index metrics so that gaps can be clearly seen and ways to fill-in the gaps solicited then academics with their deans think in-depth to reach the solution.

The results contribute to both academics’ research productivity growth and higher education research literature in Ethiopia.

Funding

The researchers did not collect funds from any organizations.

Researchers’ contribution

Ayetenew Abie: Initially conceived the research problem, designed the method, analysis and discussion with conclusion and suggestions. Getnet Demissie Bitew: advising and editing service in the progress of each stage. Solomon Melese Mengistie: Played advising and editing role in progress of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and give our warmest thanks to academics in their respective colleges and universities who provided us genuine and relevant data which made this work possible. We would also like to thank our sample universities (BDU, UoG and DMU) leaders and the staff members for supporting and guiding us during data gathering process. Finally, our special thanks go to Bahir Dar University for its financial support for covering data gathering and related costs.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. This study was not preregistered. The study data will be shared upon request via the first author.

Ethical Clearance Approval

Bahir Dar University, College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Research Ethics Approval Committee had offered Ethical clearance for this study writing the reference no. CEBS 0054/03/04/2022 and the study was also approved by the college vice dean office on the reference No. CEBSV/D1.3/06/022/22.

References

- Abramo, Giovanni; D’Angelo, Ciriaco Andrea (2014). How do you define and measure research productivity? Scientometrics, 101(2), 1129–1144. doi:10.1007/s11192-014-1269-8. [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, K., & Schneider, J. (2017). Some considerations about causes and effects in studies of performance-based research funding systems, Scientometrics, 11, 923–926.

- Åkerlind, Gerlese S. (2008). An academic perspective on research and being a researcher: an integration of the literature. Studies in Higher Education, 33(1), 17–31. doi:10.1080/03075070701794775. [CrossRef]

- Altıntaş, Ö. & Kutlu, O. (2021) An Inquiry on the third mission of universities: the measurement of universities’ contribution to the social, cultural and economic development of a city. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17( 4), 308-326.

- Amare, A. (200). The State of educational research in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Education, Vol. XX. (2), 19-48.

- Amare, A. (2007) Academic Freedom and the Development of Higher Education in Ethiopia: the Case of Addis Ababa University 1950–2005 (Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of East Anglia).

- Barbara Ridley (2011) Educational Research Culture and Capacity Building: The Case of Addis Ababa University, British Journal of Educational Studies, 59:3, 285-302 To link to this.

- Barney, J. B. (2001a). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 6, 643– 650.

- Barney, J. B. (2001b). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26, 1, 41–56.

- Boateng, F.K. (2020). Higher Education Systems and Institutions, Ethiopia. In Shin J.C., & Teixeria, P. (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions. Springer Nature B.V. [CrossRef]

- Brew, A.; Boud, D.; Namgung, S.; Lucas, L.; Crawford, K. (2015). Research productivity and academics’ conceptions of research. High Educ,. [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, C.; Iezzi, , E.; Ghetti, , C., Angelis, G. and Ferrari, C. (2015) A method for measuring individual research productivity in hospitals: development and feasibility. BMC Health Services Research 15:468. [CrossRef]

- Derebssa Dufera (2004). The Status of research undertaking in the Ethiopian higher institutions of learning with special emphasis on AAU. The Ethiopian Journal of Higher Education, 1( 1), 84-104.

- Deci, E. L.& Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life's domains.. Canadian Psychology,49(1), 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Demeter,M; Jele, A. & Major, Z., B. (2022) The model of maximum productivity for research universities SciVal author ranks, productivity, university rankings, and their implications Scientometrics (2022) 127:4335–4361. [CrossRef]

- Derebssa Dufera (2000). Factors influencing research undertaking in the Institution of Educational Research (IER). . In IER Proceeding on Current issues of Educational Research in Ethiopia. AAU Printing Press.

- Edgar, F., and A. Geare (2013). “Factors Influencing University Research Performance.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (5):774–792.

- Einarsen, S. Aasland, M. S. & Skogstand, A.A. (2007) Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, xx (2007) xxx – xxx.

- Fosci, Mattia; Loffreda, Lucia; Chamberlain, Andrew & Naidoo, Nelisha(2019) Assessing the needs of the research system in Ethiopia: Report for the SRIA program. The UK Department for International Development, UKAID, Research Consulting.

- Gültekin, N., Çelik, A., & Nas, Z. (2008). Advantages of universities for the cities. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 7(24), 264-269.

- Hardré, P. L., Beesley, A. D., Miller, R. L., & Pace, T. M. (2011). Faculty motivation to do research: Across disciplines in research-extensive universities. The Journal of the Professoriate, 5(1), 35–69.

- Horta, H. &. Santos, J. M. (2019): Organizational factors and academic research agendas: an analysis of academics in the social sciences, Studies in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Ibreck, Rachel & Alex, de Waal (2022) Introduction: Situating Ethiopia in genocide debates Journal of genocide research, 24(1), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2021.1992920. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. J., Vera, D., & Crossan, M. (2009). Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The Moderating role of environmental dynamism. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Kpolovie, P & Dorgu, I. (2019). Comparison of faculty’s research productivity: (H-index and citation index) in Africa. European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, Vol.7, (6), 57-100.

- Kumilachew S. A.; Gubaye A. A. ; Mohammed S. A.; Abebe D. D.; (2021). The Causes of Blood Feud in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia . African Studies, (), –. [CrossRef]

- Leech, N.L. and Haug, C.A. (2016), "The research motivation scale: validation with faculty from American schools of education", International Journal for Researcher Development, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 30-45. [CrossRef]

- Li Y and Zhang LJ (2022) Influence of Mentorship and the Working Environment on English as a Foreign Language Teachers’ Research Productivity:The Mediation Role of Research Motivation and Self-Efficacy.Front. Psychol. 13:906932. [CrossRef]

- Mathies, C., Kivisto, J., & Birnbaum, M. (2019). Following the money? Performance-based funding and the changing publication patterns of Finnish academics, Higher Education, 79:21–37. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education(MoE) (2018) Ethiopian education development road map. 2018-2030. AddisAbaba (un published doc).

- Moed, H. F. (2005). Citation analysis in research evaluation. Springer.

- Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MoSHE)(2020). Differentiating the higher education system of Ethiopia: Study report, Addis-Ababa, MoSHE.

- Njuguna, F., & Itegi, F. (2014). Research in institutions of higher education in Africa: challenges and prospects. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Ololube, N. P., Kpolovie, P. J., & Makewa, L. N. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of research on enhancing teacher education with advanced instructional technologies. IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- O’Meagra, K., Bennett, J. C., & Neihaus, E. (2016). Left unsaid: The role of work expectations and psychological contracts in faculty careers and departure. The Review of Higher Education, 39(2), 269–297.

- Pring, R. (2001) The Virtues and vices of an educational researcher. Journal of Philosophy of Education Vol.35, No.3.

- Quimbo, Maria Ana T. & Sulabo, Evangeline C. (2014). Research productivity and its policy implications in higher education institutions. Studies in Higher Education, 39(10), 1955– 1971. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.818639. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A.

- Stupnisky, R. H., Weaver-Hightower, M., & Kartoshkina, Y. (2015). Exploring and testing predictors of newfaculty success: A mixed method study. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 368–390. [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R. H., Hall, N. C., & Pekrun, R. (2019b). The emotions of pretenure faculty: Implications for teaching and research success. The Review of Higher Education, 42(4), 1489–1526. [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R. H., Orenz, A.B., NelsonLaird, T. F. (2019a). How does faculty research motivation type relate to success? A test of self determination theory. International Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 98, 25-35. [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R.H., Larivière, V., Hall, N.C. & Omojiba, O.(2022)’ Predicting Research Productivity in STEM Faculty:The Role of Self-determined Motivation. Res High Educ (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tekeste Negash (1990). The crisis of Ethiopian Education. Implications for nation building, Uppsala University: Uppsal Education Report No. 29.

- Tekeste Negash (1996). Rethinking education in Ethiopia. Nordiska Africanistitutet, Uppsala.

- UNESCO, “UIS Statistics,” 2019. [Online]. Available: http://data.uis.unesco.org/.[Accessed 2 July 2022].

- UNESCO, “UNESCO Science Report Towards 2030UNESCO, Paris, 2016.

- Uwizeye D.; Karimi F.; Thiong'o, C.; Syonguv, J.; Ochieng, V.; Kiroro, F.; Gateri , A.; Anne M. Khisa, A. & Wao, H. ( 2021) Factors associated with research productivity in higher education institutions in Africa: a systematic review . AAS Open Research. [CrossRef]

- Vera D., Crossan, M. (2004).Strategic leadership and organizational learning. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 29(2), 222–240.

- Walker, G. J., & Fenton, L. (2013). Backgrounds of, and factors affecting, highly productive leisure researchers. Journal of Leisure Research, 45(4), 537.

- Wood, F. 1990. Factors influencing research performance of university academic staff. Higher Education 19: 81– 100.

- Wubalem, G. G. & Sarangi, I.(2019). The role and status of research: The case of Ethiopian higher education Institutions. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 8(553) 297-301. [CrossRef]

- Yallew, A. T., & Dereb, A. (2022). Ethiopian-affiliated Research in Scopus and Web of Science: A Bibliometric Mapping. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 21(2), 22–46.

- Zaval, N. C. & Schneijderberg, C. (2020). Mapping the field of research on African higher education: a review of 6483 publications from 1980 to 2019, Higher Education (2022) 0.3 83:199–233. [CrossRef]

- Zhizhen, & Erling, L.(2022). Does industry-university-research cooperation matter? Analysis of its coupling effect on regional innovation and economic development. Chinese Geographical Science, 32(5): 915−930. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).