Submitted:

22 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

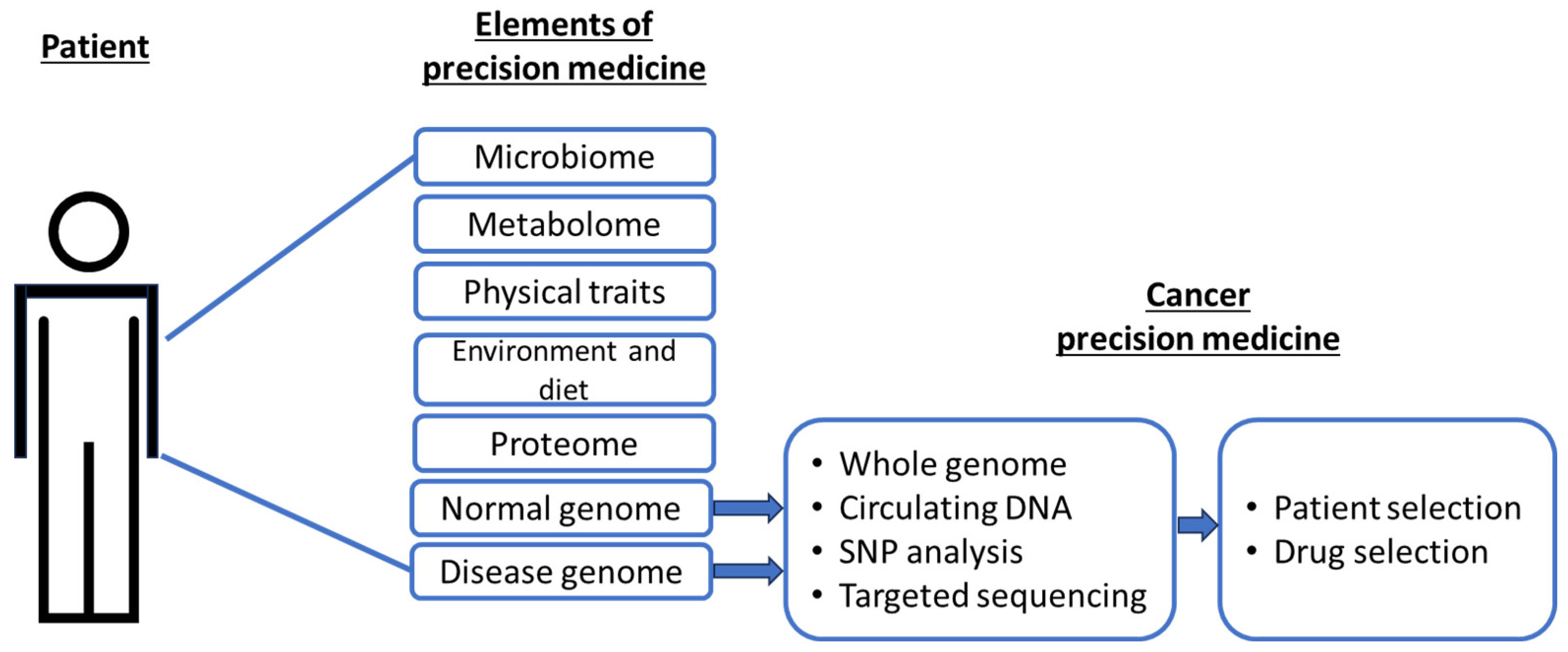

1. Precision Cancer Medicine

2. Cytokine pathways as therapeutic targets

3. Cells of cytokine origin

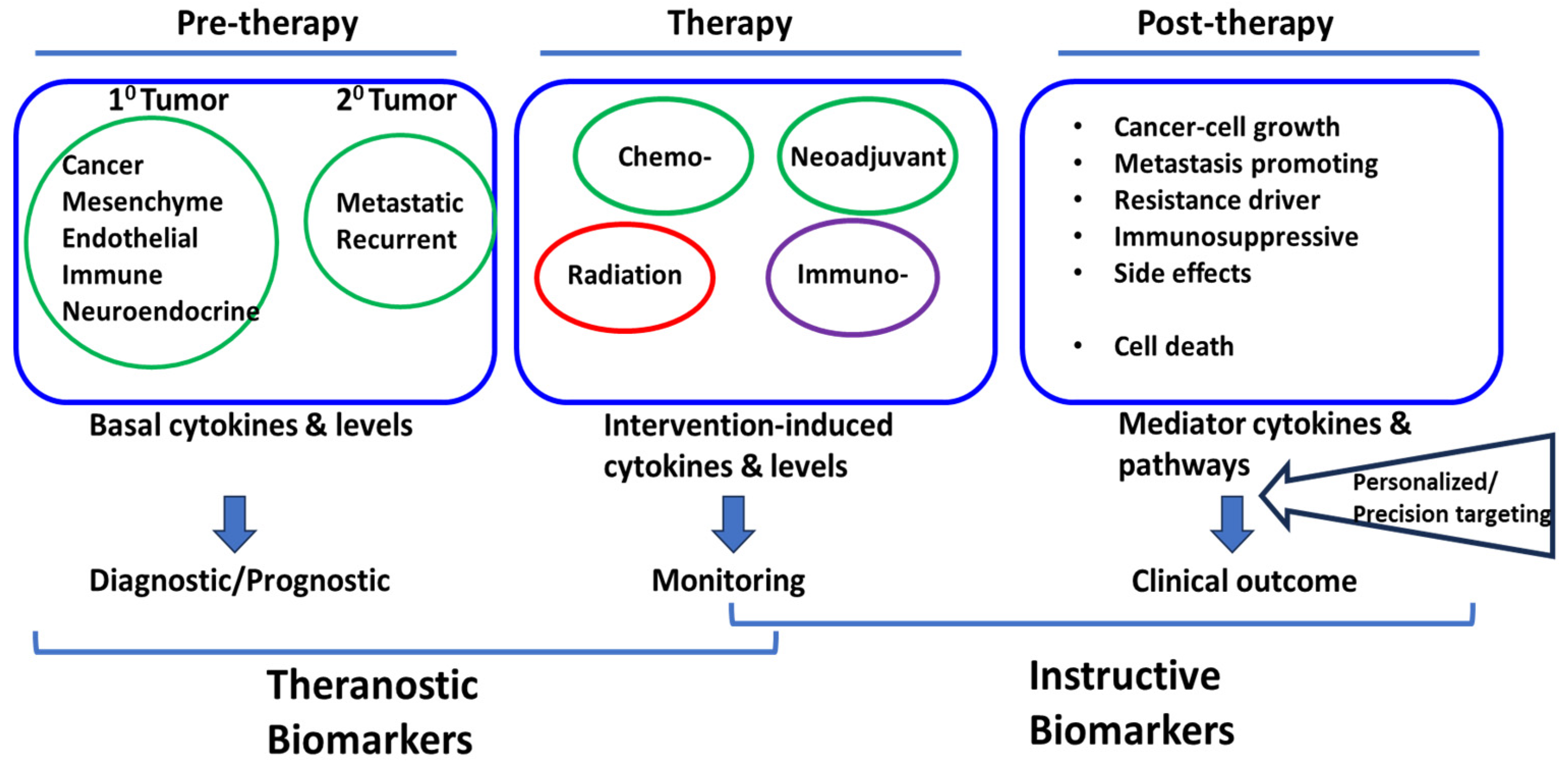

4. Cytokine responses in solid-tumors therapy: an emerging theme in cancer precision medicine

5. Cytokine responses to chemotherapy and radiation

6. Role of cytokines post chemo- or radio-therapy

7. Challenges in cytokine-directed precision approach

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mathur, S.; Sutton, J. Personalized medicine could transform healthcare. Biomed Rep 2017, 7, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadee, W.; Dai, Z. Pharmacogenetics/genomics and personalized medicine. Hum Mol Genet 2005, 14, R207–R214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agúndez, J.A.G.; García-Martín, E. Editorial: Insights in Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics: 2021. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 907131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, R.A.; Reif, D.M.; Moore, J.H. Combinatorial pharmacogenetics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005, 4, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastry, B.S. Pharmacogenetics and the concept of individualized medicine. Pharmacogenomics J 2006, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tourneau, C.; et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J.L. Giving Up on Precision Oncology? Not So Fast! Clin Transl Sci 2017, 10, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreschi, K.; et al. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet 2021, 397, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noack, M.; Miossec, P. Selected cytokine pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Immunopathol 2017, 39, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, R.; et al. Interleukin (IL)-17 Versus IL-23 Inhibitors: Which Is Better to Treat Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis and Mild Psoriatic Arthritis in Dermatology Clinics? J Rheumatol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Moyaert, H.; et al. A blinded, randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of lokivetmab compared to ciclosporin in client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2017, 28, 593–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maini, R.N.; et al. Double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, tocilizumab, in European patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had an incomplete response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 54, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardona-Pascual, I.; et al. Effect of tocilizumab versus standard of care in adults hospitalized with moderate-severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Med Clin (Engl Ed) 2022, 158, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi-Amoabeng, D.; et al. Clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients treated with tocilizumab: An individual patient data systematic review. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 2516–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. A living WHO guideline on drugs to prevent covid-19. in British Medical Journal 2021, n526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, W.H. Continuous infusion recombinant interleukin-2 (rIL-2) in adoptive cellular therapy of renal carcinoma and other malignancies. Cancer Treat Rev 1989, 16 (Suppl A), 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berraondo, P.; et al. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer 2019, 120, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarsheth, N.; Wicha, M.S.; Zou, W. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayana, S.; Khanlou, H. Maraviroc: a new CCR5 antagonist. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009, 7, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndegwa, S. Maraviroc (Celsentri) for multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1. Issues Emerg Health Technol 2007, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis, K.S.; et al. Cytokine-based Cancer Immunotherapy: Challenges and Opportunities for IL-10. Anticancer Res 2021, 41, 3247–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roufas, C. The Expression and Prognostic Impact of Immune Cytolytic Activity-Related Markers in Human Malignancies: A Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; et al. Targeting macrophages: a novel treatment strategy in solid tumors. J Transl Med 2022, 20, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, H.; et al. Prospects of IL-2 in Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 9056173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yui, M.A.; et al. Preferential activation of an IL-2 regulatory sequence transgene in TCR gamma delta and NKT cells: subset-specific differences in IL-2 regulation. J Immunol 2004, 172, 4691–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliard, X.; et al. Simultaneous production of IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-gamma by activated human CD4+ and CD8+ T cell clones. J Immunol 1988, 141, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershko, A.Y.; et al. Mast cell interleukin-2 production contributes to suppression of chronic allergic dermatitis. Immunity 2011, 35, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granucci, F.; et al. Inducible IL-2 production by dendritic cells revealed by global gene expression analysis. Nat Immunol 2001, 2, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.S.; et al. IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 2008, 111, 5326–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromadnikova, I.; et al. Influence of In Vitro IL-2 or IL-15 Alone or in Combination with Hsp 70 Derived 14-Mer Peptide (TKD) on the Expression of NK Cell Activatory and Inhibitory Receptors on Peripheral Blood T Cells, B Cells and NKT Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0151535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommen, D.S.; et al. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat Med 2018, 24, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; et al. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 1996, 381, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G.; et al. Primary, syncytium-inducing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates are dual-tropic and most can use either Lestr or CCR5 as coreceptors for virus entry. J Virol 1996, 70, 8355–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; et al. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature 1996, 384, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; et al. Review of precision cancer medicine: Evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat Rev 2020, 86, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedesser, J.E.; Ebert, M.; Betge, J. Precision medicine for metastatic colorectal cancer in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2022, 14, 17588359211072703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, K. Optimizing immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; et al. Identification of immune checkpoint and cytokine signatures associated with the response to immune checkpoint blockade in gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2021, 70, 2669–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticelli, A.; et al. The role of immune profile in predicting outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 974087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.U.; Yoon, H.K. Potential predictive value of change in inflammatory cytokines levels subsequent to initiation of immune checkpoint inhibitor in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cytokine 2021, 138, 155363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achyut, B.R.; Yang, L. Transforming growth factor-beta in the gastrointestinal and hepatic tumor microenvironment. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desoteux, M.; et al. Transcriptomic evidence for tumor-specific beneficial or adverse effects of TGFbeta pathway inhibition on the prognosis of patients with liver cancer. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dranoff, G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, M.; et al. Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, J.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced senescence, an adaptive mechanism driving resistance and tumor heterogeneity. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 2385–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, G.; et al. The injury response to DNA damage in live tumor cells promotes antitumor immunity. Sci Signal 2021, 14, eabc4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotti, F.; et al. Chemotherapy activates cancer-associated fibroblasts to maintain colorectal cancer-initiating cells by IL-17A. J Exp Med 2013, 210, 2851–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reers, S.; et al. Cytokine changes in response to radio-/chemotherapeutic treatment in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar]

- Edwardson, D.W.; Parissenti, A.M.; Kovala, A.T. Chemotherapy and Inflammatory Cytokine Signalling in Cancer Cells and the Tumour Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1152, 173–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sijde, F.; et al. Serum cytokine levels are associated with tumor progression during FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy and overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 898498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Xiong, X.; Liu, W. Prognostic Significance of the CXCLs and Its Impact on the Immune Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer. Dis Markers 2023, 2023, 5223657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Comprehensive Analysis and Identification of an Immune-Related Gene Signature with Prognostic Value for Prostate Cancer. Int J Gen Med 2021, 14, 2931–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hincu, M.A.; et al. Relevance of Biomarkers Currently in Use or Research for Practical Diagnosis Approach of Neonatal Early-Onset Sepsis. Children 2020, 7, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernot, S.; Evrard, S.; Khatib, A.M. The Give-and-Take Interaction Between the Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Cells Regulating Tumor Progression and Repression. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 850856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groysman, L.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced cytokines and prognostic gene signatures vary across breast and colorectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2021, 11, 6086–6106. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, L.; et al. Pan-drug and drug-specific mechanisms of 5-FU, irinotecan (CPT-11), oxaliplatin, and cisplatin identified by comparison of transcriptomic and cytokine responses of colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, D.; et al. Camptothecin Induces PD-L1 and Immunomodulatory Cytokines in Colon Cancer Cells. Medicines 2019, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravata, V.; et al. Cytokine profile of breast cell lines after different radiation doses. Int J Radiat Biol 2017, 93, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; et al. Colorectal cancer cell-derived CCL20 recruits regulatory T cells to promote chemoresistance via FOXO1/CEBPB/NF-kappaB signaling. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovska, V.; et al. Oxaliplatin Treatment Alters Systemic Immune Responses. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019, 4650695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistigu, A.; et al. Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 2014, 20, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaue, D.; Kachikwu, E.L.; McBride, W.H. Cytokines in radiobiological responses: a review. Radiat Res 2012, 178, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palata, O.; et al. Radiotherapy in Combination With Cytokine Treatment. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, N.; et al. Changes in the plasma levels of cytokines/chemokines for predicting the response to chemoradiation therapy in rectal cancer patients. Oncol Rep 2014, 31, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M. [Changes in serum cytokine levels in patients with malignant bone and soft tissue tumors in the course of chemotherapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1992, 19 (Suppl 10), 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; et al. Change in inflammatory cytokine profiles after transarterial chemotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytokine 2013, 64, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, C.D.; Gurbilek, M.; Koc, M. Prognostic value of interferon-gamma, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the radiation response of patients diagnosed with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and glioblastoma multiforme. Turk J Med Sci 2018, 48, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M. The Role of Proinflammatory Cytokine Interleukin-18 in Radiation Injury. Health Phys 2016, 111, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.T.; et al. Circulating interleukin-18 as a biomarker of total-body radiation exposure in mice, minipigs, and nonhuman primates (NHP). PLoS One 2014, 9, e109249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgstrom, E.; Ohlsson, T.G.; Eriksson, S.E. Cytokine evaluation in untreated and radioimmunotherapy-treated tumors in an immunocompetent rat model. Tumour Biol 2017, 39, 1010428317697550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, B.C.; et al. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 2488–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, L.H.; et al. The Inflammatory Cytokine Profile of Patients with Malignant Pleural Effusion Treated with Pleurodesis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiamulera, M.M.A.; et al. Salivary cytokines as biomarkers of oral cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; et al. Nanomedicine therapies modulating Macrophage Dysfunction: a potential strategy to attenuate Cytokine Storms in severe infections. Theranostics 2020, 10, 9591–9600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Caro, G.; et al. Circulating Inflammatory Mediators as Potential Prognostic Markers of Human Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0148186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).