Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The sensitive One Health actual context, need and link with local farm livestock

2. Materials and methods

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Farm livestock genetic resources in Romania

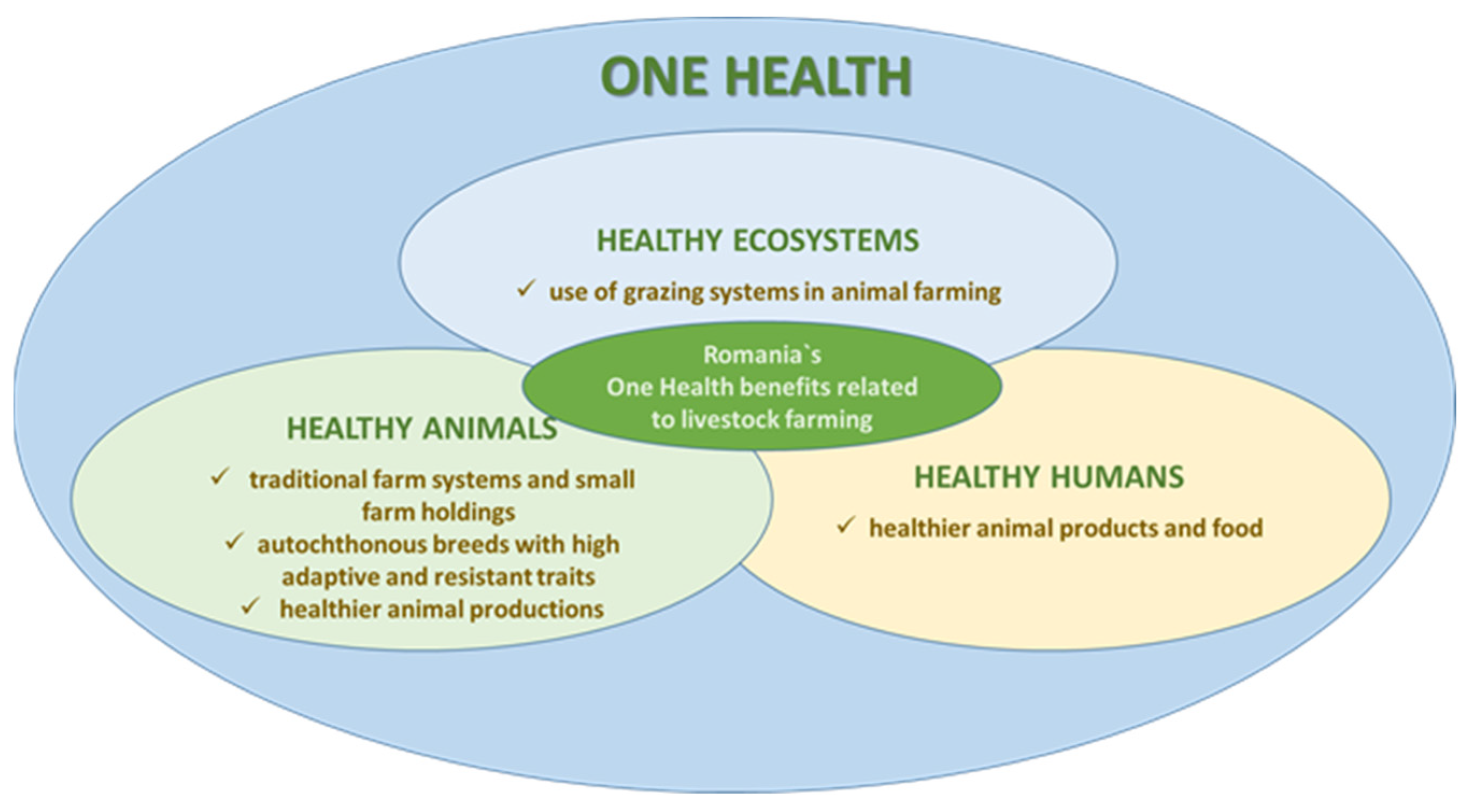

3.2. One Health and livestock farming in Romania

- Romania`s financial support for livestock farming

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Gateway, 2022. EU Global Health Strategy, Better Health For All in a Changing World. Publications Office of the European Union, ISBN 978-92-76-60497-6, EW-04-22-331-EN-N. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/international_ghs-report-2022_en.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Nitya Mohan Khemka; Srinath Reddy, Eds. Accelerating Global Health: Pathways to Health Equity for the G20. September 2023, Observer Research Foundation, pp. 1-8.

- Beaglehole, R.; & Bonita, R. What is global health? Global health action. 2010, 3, 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142. [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, P.; Conti, L. Links among human health, animal health, and ecosystem health. Annual review of public health, 2013, 34, 189–204. [CrossRef]

- Pungartnik, P. C.; Abreu, A.; Dos Santos, C. V. B.; Cavalcante, J. R.; Faerstein, E.; Werneck, G. L. The interfaces between One Health and Global Health: A scoping review. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2023, 16, 100573. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J. S.; Jeggo, M., Daszak, P.; Richt, J. A. (Eds.). One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. A.; Sankaran, N. Emergence of epidemic diseases: zoonoses and other origins. Faculty reviews, 2022, 11, 2. [CrossRef]

- WOAH and OIE, 2021. Protecting animals, preserving our future. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Internationa_Standard_Setting/docs/pdf/WGWildlife/A_Wildlifehealth_conceptnote.pdf.

- SWP, 2023. “One Health” and Global Health Governance Design and implementation at the international, European, and German levels, SWP Comment 2023/C 43, 27.07.2023, 8 Seiten, doi:10.18449/2023C43. Available online: https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2023C43/ (accessed on 04 August 2023).

- Horefti E. The Importance of the One Health Concept in Combating Zoonoses. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 2023, 12(8), 977. [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Chisholm., D.; Dua, T.; Laxminarayan, R.; Medina-Mora, M. E. editors. Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders. Disease Control Priorities, third edition, volume 4. Washington, DC: World Bank. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; McNab, C.; Olson, R. M.;Bristol, N.; Nolan, C.; Bergstrøm, E.; Bartos, M.; Mabuchi, S.; Panjabi, R.; Karan, A.; Abdalla, S. M.; Bonk, M.; Jamieson, M.; Werner, G. K.; Nordström, A.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Phelan, A. How an outbreak became a pandemic: a chronological analysis of crucial junctures and international obligations in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (London, England), 2021, 398(10316), 2109–2124. [CrossRef]

- De Sadeleer, N., & Godfroid, J. (2020). The Story behind COVID-19: Animal Diseases at the Crossroads of Wildlife, Livestock and Human Health. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 11(2), 210-227. [CrossRef]

- MADR, 2014. National Rural Development Programme for the 2014-2020 Period, Bucharest, Romania.

- MIPE, 2022. Programul Dezvoltare Durabilă 2021-2027, Available online: https://mfe.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ccd9ae994ca747e93c52ec9c97fc4c39.pdf.

- Regulament UE 1305/2013. REGULAMENTUL (UE) NR. 1305/2013 AL PARLAMENTULUI EUROPEAN ȘI AL CONSILIULUI din 17 decembrie 2013 privind sprijinul pentru dezvoltare rurală acordat din Fondul european agricol pentru dezvoltare rurală (FEADR) și de abrogare a Regulamentului (CE) nr. 1698/2005 al Consiliului, Availabel online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1305 (accessed on 07 February 2023).

- Regulament UE 807/2014. REGULAMENTUL DELEGAT (UE) NR. 807/2014 AL COMISIEI din 11 martie 2014 de completare a Regulamentului (UE) nr. 1305/2013 al Parlamentului European și al Consiliului privind sprijinul pentru dezvoltare rurală acordat din Fondul european agricol pentru dezvoltare rurală (FEADR) și de introducere a unor dispoziții tranzitorii, Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0807&from=EN (accessed on 07 February 2023).

- Regulamentului (UE) 1012/2016. Regulamentul (UE) 2016/1012 al Parlamentului European și al Consiliului din 8 iunie 2016 privind condițiile zootehnice și genealogice aplicabile ameliorării animalelor de reproducție de rasă pură, a porcilor de reproducție hibrizi și a materialului germinativ provenit de la acestea, comerțului cu acestea și introducerii lor în Uniune și de modificare a Regulamentului (UE) nr. 652/2014 și a Directivelor 89/608/CEE și 90/425/CEE ale Consiliului, precum și de abrogare a anumitor acte în sectorul ameliorării animalelor („Regulamentul privind ameliorarea animalelor”), Available onșine: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R1012&from=LV (accessed on 07 February 2023).

- MADR, 2023. PS CAP 2023-2027, Available online: https://www.madr.ro/planul-national-strategic-pac-post-2020/implementare-ps-pac-2023-2027/ps-pac-2023-2027.html (accessed on 02 April 2023).

- Romania’s Sustainable Development Strategy 2030, Available online: http://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Romanias-Sustainable-Development-Strategy-2030.pdf.

- FAO, 2021. Domestic animal diversity information system (DAD-IS). Available online: http://www.fao.org/dad-is/en/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH. 2022. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022-2026). Working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Draganescu, C. 2003. Romanian strategy for a sustainable management of Farm Animal Genetic Resources. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Environment. Country report for Animal Genetic Resources Management to the Food and Agricultural Organisation.

- Gherghinescu, O.. 2008. Poverty and Social Exclusion in Rural Areas: Romania.

- Page, N.; Popa, R.; Gherghiceanu, C.; Balint, L. Linking high nature value grasslands to small-scale farmer incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania. In: Mt. Hay Meadows Hotspots Byodiversity Tradit. Cult. Ghimeş, 2011.

- Fischer, J.; Hartel, T.; Kuemmerle, T. Conservation policy in traditional farming landscapes. Conserv. Lett., 2012, 5, 167–175.

- Mikulcak, F.; Newig, J.; Milcu, A.I.; Hartel, T.; Fischer, J. Integrating rural development and biodiversity conservation in central Romania. Environ. Conserv., 2013, 40, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- ANZ, 2023. Available online: https://www.anarz.eu/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- MADR, 2023. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Wainwright, W.; Glenk, K.; Akaichi, F.; Moran, D. Conservation contracts for supplying Farm Animal Genetic Resources (FAnGR) conservation services in Romania, Livestock Science, 2019, 224, pp. 1-9, ISSN 1871-1413. [CrossRef]

- Juvančič, L.; Slabe-Erker, R.; Ogorevc, M.; Drucker, A.G.; Erjavec, E.; Bojkovski, D. Payments for Conservation of Animal Genetic Resources in Agriculture: One Size Fits All?. Animals (Basel). 2021, 11(3):846. [CrossRef]

- Minea, G.; Ciobotaru, N.; Ioana-Toroimac, G.; Mititelu-Ionuș, O.; Neculau, G.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Designing grazing susceptibility to land degradation index (GSLDI) in hilly areas. Scientific reports, 2022, 12(1), 9393. [CrossRef]

- META, EEB, 2020. Future farming: A Romanian recipe for European livestock farming. Available online: https://meta.eeb.org/2020/06/22/future-farming-a-romanian-recipe-for-european-livestock-farming/ (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Romania-Insider, 2017. Romania wants to revive local pig breeds. Available online: https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-revive-local-pig-breeds (accessed on 01 August 2023).

- VOLT, 2020. The Situation of Romanian Agriculture. Available online: https://www.voltromania.org/en/agriculture (accessed on 04 September 2023).

- GOV, 2018. Program de sprijin pentru crescătorii de porci din rasele Bazna și Mangalița. Available online: https://www.gov.ro/ro/guvernul/sedinte-guvern/program-de-sprijin-pentru-crescatorii-de-porci-din-rasele-bazna-i-mangalita (accessed on 09 August 2023).

- MADR, 2023. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/proiecte-de-acte-normative/7981-proiect-hg-bazna-si-sau-mangalita-2023.html (accessed on 09 August 2023).

- MADR, 2019. Ordin privind aprobarea Planului sectorial pentru cercetare-dezvoltare din domeniul agricol şi de dezvoltare rurală al Ministerului Agriculturii şi Dezvoltării Rurale, pe anii 2019-2022, “Agricultură şi Dezvoltare Rurală—ADER 2022” Nr. 341/10.06.2019. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/acte-normative-aprobate/download/3715_be9e26b5bf014d426bab0f79cde03c85.html (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- ANZ, 2019. Available online: https://www.anarz.eu/AnarzAdministratorSite/CMSContent/20190327%20Comunicat%20privind%20aprobarea%20de%20catre%20ANZ%20a%20programului%20de%20conservare%20al%20rasei%20locale%20de%20taurine%20Sura%20de%20stepa.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Şonea C. G.; Socol C.T.; Criste F. L. Current perspectives for Mangalica and Bazna pigs breeding for efficient biodiversity management, genetic conservation and animal improvement in Romania, Rev Rom Med Vet, 2020, 30(1), 29-33.

- INSSE, 2022. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro/tags/comunicat-efective-animale (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- APIA, 2023. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/materiale-de-informare/materiale-de-informare-anul-2023/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Asociatia Aberdeen Angus Romania, 2023, Available online: https://aberdeenangus.ro/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- ACVBR-SIM, 2023, Available online: https://baltataromaneasca.ro/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Hofstetter, P.; Frey, H.; Gazzarin, C.; Wyss, U.; Kunz, P. Dairy farming: Indoor v. pasture-based feeding. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 2014, 152(6), 994-1011. [CrossRef]

- AGORINTEL, 2023. Preț lapte 2023. Available online: https://agrointel.ro/246786/pret-lapte-2023-cat-primesc-fermierii-pe-litru-la-procesator-si-vanzare-directa/ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- MADR, 2021. Dinamica efectivelor şi a producţiei de carne în perioada 2015-2020. https://www.madr.ro/cresterea-animalelor/ovine-si-caprine.html (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Socol C.T.; Criste F.L.;Rusu A.V.; Mihalca I. Perspectives on reproductive biotechnologies for FAnGR breeding and conservation, Porc Res, 2015, 5(1), 31-38.

- Criste, F.L.; Socol, C.T.; Maerescu, C.; Lup, F.; Șonea, G.C. Survey of bovine livestock resources in Salaj county, Analele Univ. din Oradea, Fascicula: Ecotox. Zooteh. Teh. Ind. Alim., 2021, XX/A 25-30.

- Rossetti, C.; Genualdo, V.; Perucatti, A.; Incarnato, A.; Nicolae, I.. Genetic screening between Italian and Romanian water buffalo, Journal of Applied Animal Research, 2023, 51:1, 540-545. [CrossRef]

- Chereches, I.; Fitiu, A.; Socol, C.T. The main morpho-productive traits of the buffaloes from Salaj county, Analele Univ. din Oradea, Fascicula: Ecotox. Zooteh. Teh. Ind. Alim. XXI/B, 2022, 219-222.

- Ilie, D.E.; Cean, A.; Cziszter, L.T.; Gavojdian, D.; Ivan, A.; Kusza, S. Microsatellite and Mitochondrial DNA Study of Native Eastern European Cattle Populations: The Case of the Romanian Grey. PloS one, 2015, 10(9), e0138736. [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, M.-A.; Simeanu, D.; Gorgan, D.-L.; Ciorpac, M.; Creanga, S. Analysis of Phylogeny and Genetic Diversity of Endangered Romanian Grey Steppe Cattle Breed, a Reservoir of Valuable Genes to Preserve Biodiversity. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2059. [CrossRef]

- Socol C.T.; Şonea C.G.; Maerescu C.; Criste F.L. Comparative analysis of total RNA isolation procedures from small adipose tissue samples in sheep, Rev Rom Med Vet, 2021, 31(3), 62-66.

- Giovannini, S.; Strillacci, M. G.; Bagnato, A.; Albertini, E.; Sarti, F.M. (Genetic and Phenotypic Characteristics of Belted Pig Breeds: A Review. Animals, 2023, 13(19), 3072. [CrossRef]

- ANZ, 2016. Raport de activitate ANZ pe anul 2015. Available online: https://www.anarz.eu/AnarzAdministratorSite/CMSContent/Relatii%20publice%202016/20160208%20Raport%20de%20activitate%20ANZ%20pe%20anul%202015.pdf.

- Socol C.T.; Iacob L.; Mihalca I.; Criste L.F.; Șonea G.C.; Doroftei F., Romanian Gene Bank: Perspectives and Aspects for Farm Animal Genetic Resources Conservation Lucrări științifice Zootehnie și Biotehnologii, Timişoara, Agroprint, 2015, 48(1), 394-398.

- Otu, A.; Effa, E.; Meseko, C.; Cadmus, S.; Ochu, C.; Athingo, R.; Namisango, E.; Ogoina, D.; Okonofua, F.; Ebenso, B. Africa needs to prioritize One Health approaches that focus on the environment, animal health and human health. Nature medicine, 2021, 27(6), 943–946. [CrossRef]

- Stadtländer C T. One Health: people, animals, and the environment. Infection ecology & epidemiology, 2015, 5, 30514. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2020. Biodiversity and the livestock sector—Guidelines for quantitative assessment—Version 1. Rome, Livestock Environmental Assessment and Performance Partnership (FAO LEAP). [CrossRef]

- King LJ. One Health and food safety. In: Institute of Medicine (US). Improving Food Safety Through a One Health Approach: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012. A8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114498/.

- Garcia, S. N.; Osburn, B. I.;Cullor, J. S. A one health perspective on dairy production and dairy food safety. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2019, 7, 100086. [CrossRef]

- World Population Review, 2023, Developed Countries 2023. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/developed-countries (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Agriculture.EC. At a glance: Romania’s CAP strategic plan. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-04/csp-at-a-glance-romania_en.pdf.

- Rijksoverheid.nl, 2023. Europe: Romania. Agriculture Editie 9. The rise of regenerative farming in Romania. Available online: https://magazines.rijksoverheid.nl/lnv/agrospecials/2023/01/romania (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Sutcliffe, L.; Akeroyd, J.; Page, N.; Popa, R. Combining Approaches to Support High Nature Value Farmland in Southern Transylvania, Romania. Hacquetia, 2015, 14(1) 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, L.; Paulini, I.; Jones, G.; Marggraf, R.; Page, N. Pastoral commons use in Romania and the role of the Common Agricultural Policy. International Journal of the Commons, 2013, 7(1), 58-72.

- Ingty, T. Pastoralism in the highest peaks: Role of the traditional grazing systems in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function in the alpine Himalaya. PloS one, 2021, 16(1), e0245221. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.D.; Vallin, H.E.; Roberts, B. P. Animal board invited review: Grassland-based livestock farming and biodiversity. Animal: an international journal of animal bioscience, 2022, 16(12), 100671. [CrossRef]

- Cutter, J.; Hovick, T.; McGranahan, D.; Harmon, J.; Limb, R.; Spiess, J.;Geaumont, B. Cattle grazing results in greater floral resources and pollinators than sheep grazing in low-diversity grasslands. Ecology and evolution, 2022, 12(1), e8396. [CrossRef]

- Provenza, F.D.; Kronberg, S.L.;Gregorini, P. Is Grassfed Meat and Dairy Better for Human and Environmental Health?. Frontiers in nutrition, 2019, 6, 26. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B. A.; Grace, D.; Kock, R.; Alonso, S.; Rushton, J.; Said, M. Y.; McKeever, D.; Mutua, F.; Young, J.; McDermott, J.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(21), 8399–8404. [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT, 2023. Farms and farmland in the European Union -Statistics explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/SEPDF/cache/73319.pdf.

- Clough, Y.; Kirchweger, S.; Kantelhardt, J. Field sizes and the future of farmland biodiversity in European landscapes. Conservation letters, 2020, 13(6), e12752. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, H., kirkemo, A. M., & Handeland, K. (2004). Wildlife as source of zoonotic infections. Emerging infectious diseases, 10(12), 2067–2072. [CrossRef]

- ANSVSA, 2019. Report on trends and sources of zoonoses and zoonotic agents in foodstuffs, animals and feedingstuffs. Available online: http://www.ansvsa.ro/download/raportari_ansvsa/raportari_sanatate_animala/2019-Raport-De-Tara-Al-Romaniei-Tendintele-Si-Sursele-Zoonozelor-Si-A-Agentilor-Zoonotici-In-Furaje-Alimente-Si-Animale-Incluzand-Si-Informatiile-Despre-Focarele-De-Toxiinfectii-Alimentare-Si-Rezistenta.pdf.

- Stelzl, T.; Tsimidou, M.Z.; Belc, N.; Zoani, C., ; Rychlik, M. Building a novel strategic research agenda for METROFOOD-RI: design process and multi-stakeholder engagement towards thematic prioritization. Frontiers in nutrition, 2023, 10, 1151611. [CrossRef]

- IBA, 2023. Implementarea conceptului ONE HEALTH în România. Available online: https://bioresurse.ro/en/blogs/media/implementarea-conceptului-one-health-in-romania (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- One Health Romania, 2023. Available online: https://onehealthevents.eu/index.html (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Baratta, M.; Gabai, G.; Celi, P. Editorial: One Health: The Parameters of an Eco-Sustainable Farm. Front. Vet. Sci., 2021, 8:681288. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.681288.

- Farkas, J.Z.; Kőszegi, I.R.; Hoyk, E.; Szalai, Á. Challenges and Future Visions of the Hungarian Livestock Sector from a Rural Development Viewpoint. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1206. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, 2023. Environment. Funding. Funding opportunities. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/funding_en (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- APIA, 2023. Planul Național Strategic 2023-2027 (PNS) al României » Intervenții în sectorul zootehnic. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/planul-national-strategic-2023-2027-pns-al-romaniei/interventii-in-sectorul-zootehnic/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- APIA, 2023. Măsura 10—agro-mediu şi climă din Programul Naţional de Dezvoltare Rurală (PNDR) 2014—2020. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/directia-masuri-de-sprijin-i-iasc/masuri-delegate-din-pndr/masuri-de-mediu-si-clima-finantate-prin-pndr-2014-2020/masura-10-agro-mediu-si-clima/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- APIA 2017. Annual activity report—2017. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Raport_anual_de_activitate_APIA_2017_01.02.2018.pdf.

- APIA 2018. Annual activity report—2018. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RAPORT_ANUAL_ACTIVITATE_APIA_2018_final.pdf.

- APIA 2019. Annual activity report—2019. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RAPORT_ANUAL_APIA_2019_FINAL.pdf.

- APIA 2020. Annual activity report—2020. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RAPORT_ANUAL_APIA_2020.pdf.

- APIA 2021. Annual activity report—2021. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/RAPORT-ANUAL-APIA_2021.pdf.

- APIA 2022. Annual activity report—2022. Available online: https://apia.org.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/RAPORT-ANUAL-APIA_2022_FINAL.pdf.

| Year | Total amount (million euros) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 174,06 | [85] |

| 2018 | 109,31 | [86] |

| 2019 | 148.129.011,05 | [87] |

| 2020 | 155.831.603,06 | [88] |

| 2021 | 174,135,506.70 | [89] |

| 2022 | 17.939.846,27 | [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).