1. Introduction

1.1. A ‘good’ social outcome

The last decade has seen a striking change in land use transport (LUT) policy and planning directions. While cities commonly adopt some form of triple bottom line (TBL) sustainability outcomes (economic, social, environmental) as their LUT goals, the economic goal has typically been dominant [

1]. However, high priority is now also accorded to:

cutting greenhouse gas emissions to levels compatible with keeping global temperature increase below 2°C; and,

ensuring all residents have equitable access to the benefits of their city (or region), a policy direction often linked to reducing social exclusion.

London, Malmö, Manchester, Melbourne, Singapore and Vancouver, for example, now prioritize reducing social exclusion, as does Scotland, while United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 8, 10, 11 and 16 seek greater inclusion [

2].

The specification of social goals in strategic land use transport policy and planning is not as well developed as it is for economic or environmental goals. For example, Stanley et al. [

1] identified almost twenty different ways of elaborating social goals in various urban LUT plans. The increasing interest in reducing social exclusion provides a way to increase social goal clarity for LUT policy and planning.

More broadly, discussions of social goals in western societies were initially often based around reduction of

income-based poverty and disadvantage [

3,

4]. This subsequently broadened to focus on

deprivation, a wider resource-based indication of whether people have the means of accessing goods and activities seen as ‘essentials’ in their society [

5,

6].

Social exclusion, with its focus on resources, opportunities and participation, provides a still broader way of thinking about social disadvantage, aligning well with aspirations that residents have equitable access to the benefits of their city.

Burchardt et al. [

7] (p. 30) defined social exclusion as follows: ‘An individual is socially excluded if he or she does not participate in key activities of the society in which he or she lives”. Saunders [

6] (p. 12) sees social exclusion as ‘… the end result of a set of processes that prevent people from participating in different forms of economic, social and political activity’.

In jurisdictions that use cost-benefit analysis (CBA) to inform government decision-making (e.g., Australia, Singapore, UK, parts of Europe), availability of monetized benefit/cost measures is an advantage. However, this poses a challenge for initiatives intended to reduce social exclusion, because monetization of the benefits of reducing exclusion is poorly developed. An evaluation gap thus confronts CBA-based assessment of initiatives intended to reduce social exclusion, compared to initiatives directed towards economic and environmental goals. Without three solid legs, the sustainability stool will be unstable and inclined to collapse!

Multi-criteria analysis (MCA) can be used to aggregate monetized and non-monetized impacts for evaluation, using a rating mechanism of some form to aggregate impacts into a single measure of project or initiative merit. A resulting challenge, for those who are believers in the individual preferences value judgment on which CBA is largely based [

8], is that rating across the various types of impact is often performed by an expert or group of experts, fundamentally at odds with this value judgment. However, in principle, groups of affected/interested stakeholders can be asked to rate the consequences of initiatives across monetary, physical and intangible effects, to form a view of overall initiative value from their perspectives (as they can in CBA). Hickman and Dean [

9] (p. 692) argue, however: ‘Where impacts cannot be monetized or quantified, they are often given less weight’.

Monetizing societal benefits of reducing social exclusion provides a means of closing, or at least substantially reducing, the social goal evaluation gap and deliver a more balanced CBA-based evaluation platform across goal areas. Some might object to the idea of putting a monetary value on reducing exclusion, arguing (perhaps) that reducing exclusion should be treated solely as a matter of rights/social justice, whereas monetization implies trade-offs are always possible between goals. However, limits can be set on the extent to which society is prepared to countenance monetized assessment of trade-offs between goals in evaluation [

8]. Using a capabilities framework through which to consider social exclusion recognizes the importance of

societal deliberation about (service) thresholds for inclusion, inviting discussion of rights/social justice issues [

10,

11,

12]. If there are demonstrable societal benefits from reducing exclusion, understanding the monetized scale of those benefits can complement rights/justice-based arguments for inclusion and inform societal deliberation about whether trade-offs might, or might not, be countenanced [

13]. As Short [

14] (p. 3) argues, ‘…social inclusion has positive benefits beyond being more equitable’ (e.g., savings in health and welfare system costs).

1.2. Social transit and its evaluation gap

PT services in Australian cities illustrate the challenges posed by the social evaluation gap. These services rely on government funding support, because of low cost-recovery rates from fares [

1]. Demonstrating that services create

wider societal benefits, not reflected in service-provider revenues or in direct user benefits, provides an economic rationale for government service support.

Table 1 summarises currently monetized benefits of PT, distinguishing

mass transit from

social transit. Mass transit mainly caters for heavy passenger flows (e.g., rail, trunk commuter bus), while social transit mainly provides mobility opportunities for people who cannot, or choose not to, travel by car or active transport, enabling them to better meet their needs and participate in opportunities available in their society (e.g., local bus). At the risk of over-simplification, mass transit mainly takes people to/from their neighbourhood, while social transit mainly takes them around their neighbourhood, or connects them to mass transit.

Both PT service types provide

user benefits (

Table 1). Major

wider societal benefits from mass transit (also known as

external benefits) include congestion cost savings and agglomeration economies (economic benefits), together with lower greenhouse gas emissions (an environmental benefit), generally measurable in money terms. Accordingly, mass transit improvements are well placed to be argued within a CBA framework, often assisted by Government guidelines [

15,

16].

Wider benefits of social transit flow from fewer people being socially excluded because of poor mobility opportunities. Exclusion creates costs for both the excluded person and for wider society, such as through higher health and welfare system costs. Savings in these wider costs are rarely monetized as benefits attributable to the initiative(s) that generated the savings, creating the social evaluation gap confronting social transit and illustrating the problem that needs to be overcome for more balanced CBA in support of sustainable land transport.

Under funding constraints, governments seeking decision-making guidance from CBA may support mass transit over social transit, partly because wider benefit monetization is easier for mass transit. Road improvements are also well advanced for benefit monetization, supporting road funding bids. There is thus a potential evaluation bias against improvements to social transit, as recognised in the recent Socially Inclusive Transport Strategy for England’s north:

The difference to current ways of assessing transport schemes: Social inclusion and equality considerations are often secondary in transport decision-making when compared to factors such as journey time savings and economic benefits. The emphasis on these factors is entrenched in practice and policy and results in fundamentally different decisions to what would be the case if equivalent emphasis were placed on social inclusion. [

17] (p.27]

Monetizing the wider societal benefits of reducing social exclusion provides a way of resolving this problem in jurisdictions that prioritize use of CBA.

1.3. This paper

This paper suggests a way to substantially strengthen CBA-based evaluation related to social goal achievement within urban LUT policy/planning, mitigating the social goal evaluation gap. It does this by drawing on Australian research by the lead author and colleagues over the last decade or so, which has produced monetized benefit values for a range of pathways to reducing social exclusion in an LUT setting. That research has recently been repeated by the Singapore Land Transport Authority (LTA), confirming the Australian research on trip values. The main findings from that new Singaporean research are included in this paper, considerably strengthening the evidence base for application of findings.

Section 2 summarizes some of the literature on social exclusion and on monetization of pathways to reducing exclusion.

Section 3 overviews the Australian research on monetization, outlining the pathways to reducing exclusion for which monetized values have been derived.

Section 4 summarizes the values from that monetization research and presents the new Singaporean research findings. Various applications of the findings are then presented: in informing choice of service standards for social transit in Melbourne; in a CBA of improved social transit and a motorway widening in Sydney; and, in development of Friendly Streets in Singapore. More strategic application in Melbourne’s land use plan is also illustrated.

Section 5 argues for application of resulting values, which the case studies show can add real strength to the case for reducing exclusion. This will support a more balanced CBA-based evaluation framework for pursuit of more sustainable transport systems, services and outcomes. The paper builds on a recent paper in this journal [

18].

2. Literature review

2.1. Understanding social exclusion and its drivers

Social exclusion is often viewed as a multidimensional relative concept, which refers to unequal access to participation in society and links to the inability to undertake activities, drawing attention to social justice issues [

5,

6,

19]. Reflecting the multidimensional nature of social exclusion, Burchardt et al. [

7] suggest that, for operational purposes, social exclusion might be measured using four indicators of participation: consumption (income), production (e.g., employed, in-training), political engagement and social interaction. Bradshaw et al. [

20] identify the following drivers of exclusion: low income, unemployment, education, ill health, housing, transport, social capital, neighbourhood, crime and fear of crime. Factors such as age, cultural identity and gender identity, for example, are also often noted [

6,

21].

Sen [

10] argues that social justice rests on the idea of building a society where people have equal opportunities to build personal

capabilities to achieve outcomes they value, with freedom to choose how their capabilities are used. He suggests that social exclusion inhibits the achievement of capabilities [

19]. While the substance of capabilities is somewhat elusive in Sen [

10], Nussbaum [

11] identifies ten capabilities she believes are fundamental for people to achieve human dignity and respect (e.g., life; bodily health; affiliation; control over one’s environment), discussing the important idea of threshold levels needed to support achievement of capabilities. Following Beyazit [

22], Stanley & Stanley [

23] argue that the capacity to be mobile is an intermediate capability needed to achieve many of Nussbaum’s capabilities.

The literature suggests that the extent of a person’s social exclusion is likely to depend, inter alia, on a wide range of policy-relevant social conditions the person holds, including:

their sense of community: the strength of a person’s sense of attachment to their neighbourhood [

24];

their social capital: the benefit a person derives from social networks, trust and reciprocity. Bonding capital (close networks such as family) and bridging capital (more extended networks such as work colleagues) associated with social networks have been a research interest [

25,

26] and are likely to be associated with mobility opportunities; and,

their wellbeing: a person’s rating of their quality of life. Three wellbeing constructs were identified as needing consideration:

evaluative wellbeing - a measure of overall life satisfaction, called

subjective wellbeing herein [

27,

28];

affective wellbeing - an assessment of positive and negative emotional states [

29];

eudaimonic wellbeing – which refers to living a life with meaning and purpose, a desire to grow and develop to one’s full potential [

30].

Neighbourhood socio-economic characteristics are also likely to influence exclusion [

31]. Like mobility, these various potential influencing factors might be seen as intermediate requirements for achieving capabilities that support inclusion. Importantly, they are amenable to influence by government policies that facilitate opportunities to gain these conditions, such as through access to resources and/or services like education, health services, jobs and mobility [

1].

The UK Social Exclusion Unit brought the issue of transport/mobility and social exclusion to international attention [

32], others extending understanding about connections between travel, social exclusion and/or wellbeing around that time [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Authors often focussed on specific at-risk cohorts, particularly older people. The literature suggests that, in LUT settings, social exclusion may result from disadvantages or inequities in a range of areas [

39,

40], such as:

socio-demographic/personal characteristics (e.g., age, personal abilities, language, income) [

10,

11,

41];

transport system characteristics (e.g., availability, accessibility, affordability) [

32,

41,

42,

43]; and,

land use/built environment characteristics (e.g., terrain, footpaths, activity/service locations) [

1,

44,

45].

2.2. Monetizing policy-relevant factors influencing social exclusion

Research has monetized user benefits and recognized wider societal benefits from reduced exclusion attributable to bus but without monetizing those wider benefits [

46,

47]. KPMG [

48] monetize a few wider benefits of bus that might be described as ‘social’, such as health cost savings and benefits of increased volunteering, but do not comprehensively monetize wider benefits from reducing exclusion. Listing potential benefits and costs, sometimes rated is the usual way transport appraisal/evaluation approaches societal benefits from reducing social exclusion [

49].

Monetary values for changes in levels of subjective wellbeing are available [

50,

51,

52]. HM Treasury & Social Impacts Taskforce [

51] (p. 29] note, however, that ‘There is no currently recommended standard approach for monetizing wellbeing changes based on eudaimonic or affective measures’. Research evidence exists on the monetary value of changes in levels of social capital, with trust the usual focus [

53,

54]. Groot et al. [

55] have monetized the value of changes in personal network size as one measure of social capital benefits but do not distinguish between bridging and bonding capital. No monetary values have been found for changes in sense of community, neighbourhood disadvantage or for bridging and bonding social capital separately, beyond those developed in the Australian research, as summarized in

Section 4.

3. Approach and methods in Australian research on monetizing factors influencing social exclusion in a LUT setting

A direct way to monetize wider societal benefits of reducing exclusion is to identify and value specific societal costs, such as health/welfare system costs, and assess how initiatives of interest (e.g., social transit improvements) might reduce these costs. However, estimating the societal cost of exclusion is extremely difficult [

56].

Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60] have taken a different approach, identifying a context from which monetized values of policy-relevant factors likely to influence exclusion (the

pathways) might be inferred. Drawing on the literature, with risk of social exclusion the variable to be explained, they identified several influencing factors of policy interest, these being trips (an indicator of realised mobility), bridging and bonding social capital, sense of community, three constructs of wellbeing and area socio-economic disadvantage. The literature and discussions with at-risk people suggested that a range of personal characteristics were also likely to influence someone’s risk of exclusion, such as age, household income, abilities, household circumstances (e.g., presence of children), personality, residential location/remoteness, etc.

The Australian analysis has been shaped around trying to model a functional relationship of the general form:

(1) Risk of Social Exclusion = f (trips, social capital, sense of community, wellbeing, neighbourhood disadvantage, personal characteristics, household income, other household circumstances, transport difficulties, locational preferences)

Significant associations found between individual policy-relevant variables and risk of exclusion enabled monetized values to be inferred for

changes in levels of those influencing variables, as they contribute to reducing exclusion. Similar approaches have been used (for example) to estimate benefits of health therapies within a wellbeing framework [

52]. An Australian Research Council project provided the required evidence base.

1

Measurement of the risk of someone being socially excluded was based on Burchardt et al. [

7], modified for Australian circumstances [

57].

2 Risk of social exclusion was measured using five indicators, each with a defined threshold: income, employment status, political activity, social support and participation (e.g., leisure, cultural). In modelling, risk of social exclusion was treated as an ordered categorical variable, possible respondent scores ranging from zero to five, depending on the number of thresholds passed/failed. Thus, three risk factors is worse than two and two worse than one but the differences between any pair of adjacent levels may not be equal.

Data assembly began with samples of Melbourne and regional Victorian respondents to a self-completed Victorian government household travel questionnaire, respondents having the opportunity to opt into an additional comprehensive home-interview survey. People at high risk of exclusion tend not to complete travel diaries, so a special survey sought such people (e.g., at welfare offices). Surveys collected information on factors such as the five exclusion indicators, social capital, connectedness to community, wellbeing, personality, transport problems, demographics and household composition, using established measurement tools where possible.

4. Findings

4.1. Monetized pathway values

Table 2 summarises the mean sample monetized values derived by Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60] for Melbourne (in A

$2008 prices). For example, the estimated

societal value of an additional trip is ~A

$20 (2008 prices). In more formal terms, the marginal rate of substitution between trips and household income, keeping risk of social exclusion constant, is about A

$20 (2008 prices). Taking someone from a low to medium level of bridging capital is valued at ~A

$120/day (mid-range value), or around ~A

$190/day for taking someone from a medium to high level of bridging capital. The range of values for an additional trip is smaller than for most other variables, probably reflecting the longer time period over which trip values have been developed. Further research on the other variables should narrow their respective value ranges. Details of how each variable was measured are set out in the preceding paper in this journal [

18].

The monetary value of a unit change in subjective wellbeing (measured by change in the Personal Wellbeing Index score) reduces from the A

$95-125 range shown in

Table 2 if several wellbeing values are included in the same model to explain risk of social exclusion. However, Stanley et al. [

59] argue against using multiple wellbeing variables in modelling and application, because of risks of multi-collinearity. For reducing exclusion, the wellbeing value that best reflects the intended wellbeing impact of initiatives under evaluation should guide selection of the relevant wellbeing value. The values for changes in Positive Affect, Personal Growth and Positive Relations With Others go some way to closing the gap identified in relation to availability of monetized values for changes in eudaimonic and affective measures of wellbeing [

51].

Stanley et al. [

59] argued that a threshold level of subjective wellbeing may be important for inclusion, drawing on the Broaden and Build Theory of positive emotions [

61]. Stanley & Stanley [

23] tested and confirmed this idea. Following this approach,

Table 2 shows that the value of a change in subjective wellbeing is particularly high for those with the lowest starting levels of subjective wellbeing (a Personal Wellbeing Index score of under 6 on the 0-10 PWI scale). This finding suggests that the subjective wellbeing benefits associated with reducing risk of social exclusion may be most concentrated amongst those with the lowest starting levels of subjective wellbeing, who should be a focus for need identification in the policy cycle.

The modelling work by Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60] includes household income per day squared as an explanatory variable. A vital implication of this specification is that the

Table 2 values increase in inverse proportion to declining household income (conversely for increasing household income), mirroring the idea of equity weighting of benefits by household income in CBA. Also, the values increase as the number of exclusion risks confronting a person increase [

60]. These findings underline the importance of knowing

who gains and who loses in need identification and evaluation (distributional analysis). These comments do not apply to the value of increased subjective wellbeing for those with the lowest starting levels of subjective wellbeing, because household incomes have been taken into account in deriving the A

$184 value applicable to benefits to this group.

A challenge with applying the findings from this research is its lack of precedent. Consequently, some public officials have concerns about using its monetized values for initiative appraisal/evaluation, particularly trip values which are higher than result from conventional ‘rule-of-a-half’ thinking. That ‘rule’ says that the benefits from a new trip, which is generated by a transport improvement, are worth only half as much, on average, as the benefits from an existing trip that is now taken under more favourable circumstances. Stanley et al. [

60] argue that their estimated trip values are higher because they include both the rule-of-a-half benefits (to new trip makers) plus an estimate of wider societal benefits from reduced exclusion. Similarity of Melbourne and regional Victorian trip values estimated in Stanley et al. [

57] is encouraging here, as are the findings from the new Singapore research reported in

Section 4.2. and benchmarking of subjective wellbeing values against UK values.

The UK value for a one-unit increase in someone’s subjective wellbeing score for one year is an average of two values, one based on association between income and life satisfaction [

51]. An income/life satisfaction (subjective wellbeing) trade-off is also used by Stanley et al. [

59]. The UK value represented 45% of 2019 UK mean household income. The midpoint of the subjective wellbeing values in

Table 2 is 49% of sample mean household income, strikingly close to the UK percentage and a little below what has been found in another Australian income/life satisfaction analysis [

50].

These comparisons provide reassurance about the value of trips and subjective wellbeing and, by extension, of other monetized values, derived in this research stream, particularly since its income/life satisfaction trade-off settings differ from those used in the UK work [

51] and in Biddle et al. [

50]. Those sources had life satisfaction as their dependent variable in analysis. The Australian research discussed herein uses social exclusion as its dependent variable for inferring subjective wellbeing values, a different approach but producing a very similar relative valuation.

4.2. Singapore research on journeys and social exclusion

Singapore’s

Land Transport Masterplan 2040 [

62] outlines the country’s vision for an inclusive land transport system that caters to the needs of all users. This vision embraces the concept of social transit, recognising that public transport plays an important role in fostering a more inclusive society. Referencing existing methodology introduced by Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60], Singapore’s LTA has recently developed a set of initial estimates on the value of journey making to support the reduced risk of social exclusion in Singapore.

LTA has constructed a Social Exclusion Risk Index (SERI) to measure the risk of social exclusion faced by Singapore residents. Data from ongoing monthly Singapore Government surveys on personal well-being indicators in the April to July 2023 waves were used to construct a Singapore-specific SERI. The five sub-indicators, mirroring the Stanley et al. [

57] indicators of risk of social exclusion, with their respective threshold points to suit the Singapore context, are shown in

Table 3 below.

The social support sub-indicator used by LTA in SERI is different from the equivalent Stanley et al. [

57] indicator in terms of scope and emphasis. That indicator of social support assesses the availability of support from one’s social network such as family, friends or neighbours, but there were no questions in the Singapore Government surveys on personal well-being indicators that measure social support this way. LTA hence derived its social support sub-indicator using survey questions that measure the broader aspects of social integration and engagement within ones’ neighbourhood, as shown in

Table 3.

LTA did not use the political activity sub-indicator in SERI, including the civic activity sub-indicator instead. The latter measures an individual’s desire to make a positive impact on the lives of others and contribute to the betterment of society. Civic activity is considered a more comprehensive measure of social engagement in Singapore, as it includes volunteering, community service, advocacy and policy engagement. While political activity is important, it may not be as relevant to all Singaporeans as civic activity.

The following model, adapted from the Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60] specifications as closely as possible but recognizing data limitations, is used by LTA to find the monetary values of variables which were likely to influence someone’s SERI in the Singapore context. The accessibility index variable is the measure of public transport accessibility of a particular location in Singapore. Information for these variables were also collected from ongoing monthly Singapore Government surveys on personal well-being indicators in the April to July 2023 waves.

(2) SERI = f (journeys, wellbeing, household income, car ownership, age, residential region, housing type, accessibility index)

As there were no direct measures of bridging and bonding capital in current datasets, these variables were not included in the model, but could certainly be considered for future work. SERI was treated as an ordered categorical variable with possible scores ranging from zero to five in the modelling, depending on the number of thresholds passed/failed.

Table 4 summarises the mean sample monetized values derived by LTA (in S

$2023 prices), after controlling for age, residential region and housing type variables. The estimated

societal value of an additional trip to prevent someone to have the highest SERI level in Singapore is S

$29.20, which is higher than Melbourne’s at A

$20 (in 2008 prices)

4. This result adds support to the idea that increased trip making by those at risk of social exclusion of social exclusion is substantially undervalued by application of the traditional economic ‘rule-of-a-half’.

The monetary value of a unit change in someone's wellbeing in Singapore is S

$115 (2023 prices), which compares to the Melbourne range of A

$95-125 (2008 prices). Prima facie these numbers look very similar but different measurement scales and price levels cloud a simple comparison. For example, the wellbeing index used by LTA is based on the Cantril Ladder scale, with a range of 1 to 5, where 1 represents very dissatisfied and 5 represents very satisfied. In contrast, the personal wellbeing index used in Stanley et al. [

57,

58,

59,

60] spans 0 to 10, with 0 indicating not at all satisfied and 10 signifying extremely satisfied. Benchmarking against household income assist comparisons.

Section 4.1 indicated that Melbourne’s value for a one-unit change in wellbeing is approximately 49% of the sample income, which aligned closely with UK’s value at approximately 45%. The value in Singapore found by LTA is around 1/3 of average income but with a one-unit change constituting a larger change (i.e., harder to achieve) than with the Australian measure. These proportions are sufficiently close to be encouraging but warrant further exploration.

4.3. Application Case Study 1: Informing social transit service levels

Social transit is essentially provided to give people who cannot, or choose not to, travel by another mode of transportation the opportunity to participate more fully in activities within their society. This requires attention to issues such as service availability, affordability and accessibility [

42]. The idea of thresholds needed to adequately support capabilities is important here, with Nussbaum’s thinking about an ‘ample social minimum’ highly relevant, where she warns about setting a threshold so low that ‘it is less than what human dignity seems to require’ [

11] (p. 42). Reasoned community discussion about possibilities, with active involvement of disadvantaged groups, should inform that decision-making process for social transit service levels needed to support inclusion (procedural equity).

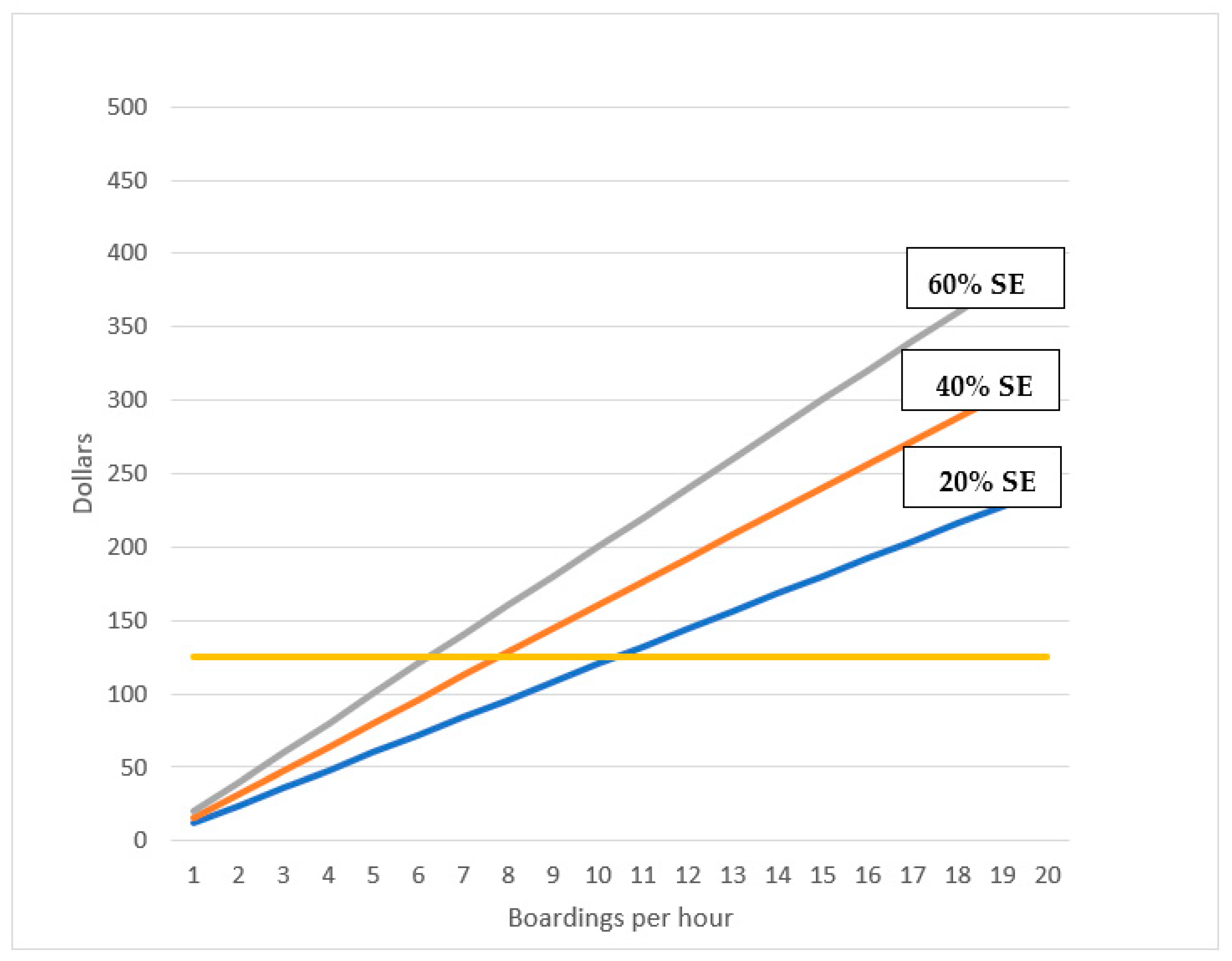

Such deliberation can be assisted by evidence on the monetized benefits of increased trip-making by people at risk of mobility-related exclusion. For example,

Figure 1 applies the trip values derived from the Melbourne research, updated to 2019 prices, to show total monetized benefits from a hypothetical new Melbourne route bus service, at different boarding levels per hour, the latter shown for between 20%-60% of service boardings being by ‘at-risk’ users. Typical service costs are around A

$125/hour. In practical terms, being ‘at-risk’ of exclusion is understood as meaning that either (1) the trip would not have been taken at all or (2) would have needed someone else to drive the trip maker (e.g., a friend or taxi driver), in the absence of the new bus service. Data on those proportions is not available but a little over 40% of Melbourne route bus passengers travelled on a concession in 2023 (to November), with just over 50% in the preceding 5 years.

5 The 40% at-risk line may thus be a guide to the current proportion of at-risk users of the Melbourne bus network, with higher proportions likely in outer growth areas.

With 40% of passengers at risk of mobility-related exclusion, the total projected benefits (rounded) at a boarding rate of 8 passengers per hour sum to a little over the estimated service cost of A

$125. At this

social break-even boarding rate, those projected benefits consist of:

6

These calculations highlight the importance of social inclusion benefits within total benefits. Without inclusion benefits, the required boarding rate for break-even would be ~16, not 8, based on user benefits plus congestion cost savings, increasing to over 20 if only user benefits are counted. Real world application to particular service opportunities needs refined estimates of user travel opportunities in the absence of the particular service under consideration but these indicative numbers clearly show the potential significance of the social inclusion benefit-driven trip values for at-risk people in making a case for improved social transit.

4.4. Application Case study 2: Sydney transport infrastructure/service improvements

Stanley et al. [

64] developed census-based indicators as proxies for the survey-based indicators of exclusion from Stanley et al. [

57]. These proxies were used to identify Greater Sydney locations where increased trip making, resulting from transport infrastructure/service improvements, was more likely to reduce exclusion. The value of additional trips was applied in four Sydney transport improvement case studies:

a new 12-kilometre Parramatta Light Rail service (estimated present value (PV) of costs of A$3.1b in 2019 prices);

M4 Outer Motorway widening (37 kilometres in length; estimated PV of costs A$2.5b);

doubling of service frequencies over a large proportion of Sydney's urban route bus services, focussed in middle and outer suburbs (Cost PV = A$4.6b); and,

doubling bus frequencies in Sydney's outer west, an area of relative socio-economic disadvantage (Cost PV = A$3.0b).

Application of trip values of A

$22.75 (2019 prices) for additional trips by those from areas of greatest risk of mobility-related exclusion substantially improved initiative benefit-cost ratios for the public transport improvements: light rail benefits more than doubled and benefits from improved bus services in Sydney’s outer west increased by half when inclusion benefits were added, dramatically improving the worth of these initiatives

8. As expected, benefits of reduced exclusion were smaller from doubling service levels across the whole bus network, still adding a useful 5% to total project benefits, with the smallest benefits from reduced exclusion attributable to the motorway upgrade. Without the benefits from reduced exclusion, the Parramatta Light Rail project looks to be a white elephant but adding those benefits results in a benefit-cost ratio of an acceptable 1.4 (at 7% real discount rate). Doubling bus services in Sydney’s outer west had a stronger BCR, at 1.9, as did doubling bus services across most of Sydney’s middle/outer suburbs.

By way of comparison, agglomeration benefits were much smaller than inclusion benefits for every project. Agglomeration benefits are counted in most such evaluations in Australia but exclusion benefits are not. The results of this case study show the serious distortion in resource allocation efficiency that results from ignoring monetized benefits of reduced exclusion. Other monetized pathway values (e.g., bridging/bonding capital) were not used in the evaluation, because of lack of evidence about how the respective transport improvements would impact levels of those pathway variables.

4.5. Application Case study 3: Friendly Streets in Singapore

The “Friendly Streets” initiative is part of LTA’s efforts to develop an inclusive land transport system in Singapore. To be introduced to all towns in Singapore by 2030, the initiative aims to bring about safer and more convenient journeys for seniors, persons with disabilities and families with young children to key amenities in their neighbourhoods. Features that promote gracious road behaviour and calmer vehicular traffic will be introduced along streets near key amenities and transport nodes with high pedestrian flows, such as widened footpaths and barrier-free at-grade crossings with priority for pedestrians.

The "Friendly Streets" initiative aligns with a broader national program called "Age Well SG", which aims to combat social isolation and loneliness among seniors by fostering active participation in social activities and community engagement. The "Friendly Streets" initiative specifically encourages seniors to venture out of their homes and explore their neighbourhoods, promoting social inclusion and fostering connections with friends and neighbours.

Traditional methods of evaluating the benefits of transport projects are not suited for assessing the social benefits of the "Friendly Streets" initiative. However, Stanley et al. [

18,

57,

58,

59,

60] 's methodology, which assigns a monetary value to journeys that reduce the risk of social exclusion, allows LTA to formally incorporate these social benefits into the appraisal process, using the Singaporean monetized values set out in

Table 4, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of the initiative's positive societal impact.

4.6. Application Case study 4: Integrated land use transport planning

Social exclusion risks are sometimes identified by vulnerable groups, sometimes by location and sometimes by both. In Melbourne, for example sustained high rates of population growth, most of which is concentrated on the urban fringe, but lagged provision of many services, including local public transport, raises red flags for social exclusion. As distance from central Melbourne increases, the rate of population growth increases, some other notable development patterns being: density, productivity, mean household incomes, local job availability, trust in other people and PT use decline; commute times (highly car dependent) and self-reported obesity increase; and, socio-economic disadvantage increases. These patterns suggest outer urban growth is likely to result in increased exclusion [

65,

66,

67,

68].

Against this background, Stanley [

68] shows how a societal needs-based strategy can be developed at city-wide level, and supported at local level, intended to both (1)

reduce social exclusion, particularly exclusion associated with rapid population growth in outer suburban areas, and (2) support

increased economic productivity. As developed for

Plan Melbourne [

68], this strategy is founded on:

working with structural economic changes occurring in the Melbourne economy, by encouraging accelerated growth of high-technology/knowledge-based activities, where agglomeration economies are important for growth, in a small number of newly designated, mainly middle-urban, National Employment and Innovation Clusters (NEICs), based around major tertiary/research institutes/hospitals where possible. The NEICs are intended to become focal points for a more compact poly-centric Melbourne and were chosen to be close enough to central/inner Melbourne to not detract from further growth of the knowledge economy in those areas of high agglomeration economies;

connecting outer growth areas more closely into NEIC labour catchments, and into central Melbourne, by high quality trunk public transport connections. This approach is expected to do more to support growth of household incomes in outer growth suburbs than would result from seeking to persuade high-tech/knowledge-based firms to locate in outer urban areas, where agglomeration potential is low;

supporting this top-down strategic approach of a more polycentric urban form with a bottom-up strategy at the local level of developing Melbourne as a series of 20-minute neighbourhoods, following thinking in Portland (Oregon). This needs to include, inter alia, timely provision of social transit, using service criteria such as outlined in

Section 4.2 above.

It should be noted that the strategic transport directions to support the above land use strategy were

not subjected to CBA, which is more appropriately applied once specific infrastructure/service improvements have been identified to achieve the strategic intents, as in the

Section 4.4 case study for Sydney. This Melbourne example is mainly about strategic socio-economic need identification, as a precursor to option development of the type evaluated in

Section 4.4.

5. Conclusions

The meaning of a good social outcome in LUT policy/planning has been relatively underdeveloped but this is changing as cities increasingly focus on reducing social exclusion, with the allied intent of providing all residents with more equitable access to the benefits of their city. This paper starts from the position that reducing exclusion is a comprehensive way to frame social goal setting for LUT policy/planning. Reducing exclusion is then, in large part, an issue of policy/planning for the availability of the means for people to be included, through (for example) provision of resources (e.g., services, infrastructure, places) and means of accessing/utilising these resources, supporting capabilities.

While reducing exclusion is a priority for many governments, the lack of monetized benefit measures associated with pathways to reduced exclusion (the social evaluation gap), in jurisdictions using CBA to inform decision-making, is likely to disadvantage implementation of initiatives with that intent. This paper aims to close, or substantially reduce, the social evaluation gap, by:

identifying several policy-relevant factors that influence social exclusion;

deriving monetary values for the societal worth of changes in levels of these factors, as they impact exclusion; and,

encouraging others to repeat these analyses to derive their own estimates and/or use the monetized values reported herein to more adequately reflect the societal benefits from reducing exclusion in policy/planning evaluations.

Several examples have been presented to show how using the values of increased trip making, by those at risk of mobility-related exclusion, can make a material difference to the case for initiatives that lead to such increased trip-making. Ignoring these benefits, in effect, imposes a CBA evaluation bias against reducing exclusion. Other pathway monetized values have not been used in the case study examples because of a lack of before/after (or dose/response) evidence of how the initiatives under evaluation would impact those pathway variable levels. Case study applications focussed on those pathways, particularly bridging social capital and subjective wellbeing, should be most informative regarding opportunities for wider application of the respective monetized values.

The monetized trip and wellbeing values, in particular, as set out in this paper for Melbourne and Singapore, provide evidence-based opportunities to improve the way CBA is applied in pursuit of more sustainable land use transport policy and planning outcomes, by overcoming the social goal evaluation gap. Inclusion of these monetized values in jurisdiction appraisal/evaluation guidelines will do much to remedy the evaluation bias that has long confronted social goal achievement and provided (unintended) institutional reinforcement of exclusion. Using pathway values set out in this paper provides a way of rectifying this inequity, supporting jurisdictions that are seeking to provide their residents with more equitable access to the benefits of their city by planting the social sustainability leg more firmly in the sustainability stool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.S.; Methodology, J.S.; Formal analysis, J.S. (Australian studies), W.Y.L & Y.H.G (Singaporean studies); Writing, J.S. (Australian research), W.Y.L. & Y.H.G. (Singaporean research); Editing, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The original Australian research on which it builds received a grant from the Australian Research Council (LP0669046: Investigating Transport Disadvantage, Social Exclusion and Well Being in Metropolitan, Regional and Rural Victoria).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for the original Australian survey was given by Monash University (2008000034 - CF08/01 62; approved 20/2/2008).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study survey

Data Availability Statement

The authors will respond to requests for data access.

Acknowledgments

John Stanley acknowledges contributions to the Australian research program from Janet Stanley, David Hensher, Dianne Vella-Brodrick, Graham Currie, Alexa Delbosc, Peter Brain and Roz Hansen. Views expressed in this paper on Singapore research on journeys and social exclusion, as well as the application case study on Friendly Streets in Singapore are the authors’ own, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Land Transport Authority, Singapore.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

LP0669046: Investigating Transport Disadvantage, Social Exclusion and Well Being in Metropolitan, Regional and Rural Victoria. |

| 2. |

For example, the Burchardt et al. [7] indicators included whether someone voted as one indicator, removed from Australian indicators because voting is compulsory. |

| 3. |

Any individual or group activity addressing issues of public concern. It can include both political and non-political actions. |

| 4. |

Based on exchange rate of A$1=S$0.88 on 21 November 2023. |

| 5. |

Unpublished State Government data. |

| 6. |

Environmental costs/benefits are excluded in these calculations, Stanley & Hensher [63] showing them to be trivial relative to the matters set out in this analysis. |

| 7. |

Based on Stanley & Hensher [63] updated to 2019 prices. |

| 8. |

Average trip values, not values adjusted by household income, were used in this analysis, to take a conservative approach. |

References

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, J.; Hansen, R. How Great Cities Happen: Integrating People, Land Use and Transport, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2023). Sustainable Development: The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Titmuss, R. Poverty and Population.; Macmillan, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living. In Fabian Tract 371; Fabian Society, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, T.; LeGrand, J.; Piachaud, D. Introduction. In Understanding Social Exclusion; Hills, J., Le Grand, J., Piachaud, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2002; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, P. Down and out: Poverty and exclusion in Australia; The Policy Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, T.; LeGrand, J.; Piachaud, D. Degrees of exclusion: developing a dynamic, multidimensional measure. In Understanding Social Exclusion; Hills, J., Le Grand, J., Piachaud, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2002; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C.; Pearce, D.; Stanley, J. An evaluation of cost-benefit analysis criteria. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 1975, 22, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, R.; Dean, M. Incomplete cost - incomplete benefit analysis in transport appraisal. Transport Reviews 2017, 38, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Social Exclusion: Concept, Application and Scrutiny. Manilla: Office of Environment and Social Development, Asian Development Bank. Social Exclusion: Concept, Application, and Scrutiny. 2000. Available online: http://adb.org.

- Nussbaum, M. Creating capabilities: The human development approach; Belnap Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J. Opportunity equity in strategic urban land use transport planning: Directions in London and Vancouver. Transport Policy 2023, 136, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, D.; McPherson, M. Economic analysis, moral philosophy, and public policy, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J.R. Social inclusion in cities. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2021, 3, 684572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Treasury (2022). Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation. Author. The Green Book. Available online: http://publishing.service.gov.uk.

- Infrastructure & Transport Ministers (2020). Australian Transport Planning and Assessment Guidelines: User Guide. Author. U User Guide. Available online: http://atap.gov.au.

- Transport for the North (2022). Socially inclusive transport strategy: Draft for consultation: November 2022. Author. TFN_SociallyInclusive_Draft-for-consultation.pdf. Available online: http://transportforthenorth.com.

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, J. Improving appraisal methodology for land use transport measures to reduce risk of social exclusion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Idea of Justice; Penguin Books, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, J.; Kemp, P.; Baldwin, S.; Rowe, R. The drivers of social exclusion. A review of the literature for the Social Exclusion Unit in the Breaking the Cycle series: Summary. Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Drivers of Social Exclusion. 2004. Available online: http://york.ac.uk.

- Silver, H. Social exclusion. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban Studies; Orum, A., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyazit, E. Evaluating social justice in transport: lessons o be learned from the capability approach. Transport Reviews 2011, 31, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, J. Equity in transport. In Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Transport Economics and Policy; Nash, C., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015; pp. 418–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.; Chavis, D. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Bowling alone. America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital | Journal of Democracy. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.; Gray, M.; Hughes, J. Social capital at work: How family, friends and civic ties relate to labour market outcomes. Research paper No. 31. Australian Institute of Family Studies. 2003. Available online: http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/respaper/stone3.html.

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Lucas, R.; Smith, H. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Wellbeing Group. Personal Wellbeing Index. Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University. Personal Wellbeing Index. 2006. Available online: http://www.acqol.com.au/instruments#measures.

- Watson, D.; Clark, I.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. Happiness is everything, or is it? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, R. Neighbourhood effects: Can we measure them and does it matter? LSE STICERD Research Paper No. CASE073, London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics. 2003. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1158964.

- Social Exclusion Unit (2003). Making the Connections: Final Report on Transport and Social Exclusion. wcms_asist_8210.pdf. Available online: http://ilo.org.

- Church, A.; Frost, M.; Sullivan, K. Transport and social exclusion in London. Transport Policy 7, 195–205. [CrossRef]

-

No way to go: Transport and social disadvantage in Australian Communities.; Currie, G., Stanley, J., Stanley, J., Eds.; Monash University, 2007; Available online: https://publishing.monasah.edu/books/nwtg-epress.html.

- Kenyon, S.; Lyons, G.; Rafferty, J. Transport and social exclusion: Investigating the possibility of promoting inclusion through virtual mobility. Journal of Transport Geography 2002, 10, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. Transport and social inclusion: Where are we now? Transport Policy 2012, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, J.; Rajé, F. Accessibility mobility and transport-related social exclusion. Journal of Transport Geography 2007, 15, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinney, J.; Scott, D.; Newbold, K. Transport mobility benefits and quality of life: a time-use perspective of elderly Canadians. Transport Policy 2009, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.D.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Yang, J.; Mohamed, M. Measures of transport-related social exclusion: A critical review of the literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, G.; Portugal, L. Understanding transport-related social exclusion through the lens of capabilities approach. Transport Reviews 2022, 42, 503–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Wretstrand, A.; Schmidt, S. Disparities in mobility among older people: Findings from a capability-based travel survey. Transport Policy 2019, 79, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, J. Public transport and social inclusion. In The Routledge Handbook of Public Transport; Mulley, C., Nelson, J., Ison, S., Eds.; Routledge, 2021; pp. 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselwhite, C.; Attard, M. Public transport use in later life. In The Routledge Handbook of Public Transport; Mulley, C., Nelson. J. and Ison, S., Eds.; Routledge, 2021; pp. 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Delbosc, A.; Currie, G. Taking it apart: Disaggregate modelling of transport, social exclusion and wellbeing. In New Perspectives and Methods in Transport and Social Exclusion Research.; Currie, G., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing, 2011; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment. Journal of the American Planning Association 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, P.; Fuller, R.; Bray, J. The case for the urban bus. The economic and social value of bus services in the metropolitan areas. Public Transport Executive Group. pteg Report Template for Office 2010. 2013. Available online: http://urbantransportgroup.org.

- Department for Transport & Mott McDonald (2014). Valuing the social impacts of public transport. Final report. Authors. Valuing the social impacts of public transport: final report.

- KPMG (2017). The true value of local bus services to society. A report to Greener Journeys. August. Microsoft PowerPoint - Greener Journeys Value for Money Update v3_290617.pptx. Available online: http://greener-vision.com.

- Department for Transport (2020). TAG Unit A4.2: Distributional Impact Appraisal. London: Author. TAG UNIT A4.2 Distributional Impact Appraisal. Available online: http://publishing.service.gov.uk.

- Biddle, N.; Edwards, B.; Gray, M.; Sollis, K. Hardship, Distress, and Resilience: the Initial Impacts of COVID-19 in Australia. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods. Microsoft Word - The initial impacts of COVID-19 in Australia - For web.docx (anu.edu.au). 2020. Available online: http://anu.edu.au.

- HM Treasury & Social Impacts Task Force (2021). Wellbeing Guidance for Appraisal: Supplementary Green Book Guidance. Authors. Wellbeing_guidance_for_appraisal_-_supplementary_Green_Book_guidance.pdf. Available online: http://publishing.service.gov.uk.

- Van Praag, B.; Carbonell-i-Ferrer, A. Happiness Quantified: A Satisfaction Calculus Approach; Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, J.; Wicker, O. The monetary value of social capital. Journal of Behavioural and Experimental Economics 2015, 57, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyanrattakorn, S.; Chang, C.-L. Valuation of trust in government: The wellbeing approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, W.; Van Den Brink, H.; Van Praag, B. The compensating income variation of social capital. Social Indicators Research 2007, 82, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R. The personal, social and economic costs of social exclusion in Scotland. The Scotland Institute. The Personal, Social and Economic costs of Social Exclusion in Scotland | Roger Cook. 2012. Available online: http://Academia.edu.

- Stanley, J.; Hensher, D.; Stanley, J.; Vella-Brodrick, D. Mobility, social exclusion and well-being: Exploring the links. Transportation Research Part A 2011, 45, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, J.; Balbontin, C.; Hensher, D. Social exclusion. The roles of mobility and bridging social capital in regional Australia. Transportation Research Part A 2019, 125, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Hensher, D.; Stanley, J.; Vella-Brodrick, D. Valuing changes in wellbeing and its relevance for transport policy. Transport Policy 2021, 110, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Hensher, D.; Stanley, J. Place-based disadvantage, social exclusion and the value of mobility. Transportation Research Part A 2022, 160, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, R. The broaden and build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 2004, 359, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Transport Authority {2019]. Land Transport Master Plan 2040. Author. LTA LTMP 2040 eReport.pdf.

- Stanley, J.; Hensher, D. Economic modelling. In New Perspectives and Methods in Transport and Social Exclusion Research; Currie, G., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J.; Hensher, D.; Wei, E.; Liu, W. Major urban transport expenditure initiatives: Where are the returns likely to be strongest and how significant is social exclusion in making the case. Research in Transportation & Business Management 2022, 43, 10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, J.; Sipe, N. Shocking the suburbs: Urban location, housing debt and oil vulnerability in the Australian city. Urban Research Program Research Paper No. 8. July. Griffiths. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Infrastructure Victoria (2022). Getting on board: Making the most of Melbourne’s buses. Discussion Paper. Author. Get on board. Available online: http://infrastructurevictoria.com.au.

- Rosier, K.; McDonald, M. The relationship between transport and disadvantage in Australia. CAFC Resource Sheet, August. Australian Institute of Family Studies. rs4_2.pdf. 2011. Available online: http://aifs.gov.au.

- Stanley, J. Land use/transport integration: Starting at the right place. Research in Transportation Economics 2014, 48, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (2014). Plan Melbourne: Metropolitan Planning Strategy. Retrieved 2 November 2023 from Introduction-Plan-Melbourne-May-2014-v3.pdf.

- Ministry of Health, Singapore. (16 November 2023). Age Well SG to support our seniors to age actively and independently in the community [Press Release]. 16 November. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/age-well-sg-to-support-our-seniors-to-age-actively-and-independently-in-the-community.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).