1. Introduction

Skills for producing behaviors synchronously with external cuing are crucial for professionals, such as musicians [

1], dancers [

2,

3], and athletes [Janzen et al., 2014–6). Sensorimotor synchronization is critical to foster such skills [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. As demonstrated by numerous previous studies, long-term musical practice shapes the music brain characterized by highly sensitive sound stimuli and stimulus-driven precise motor control ability [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Further, it is believed that such musical expertise enhances the cognitive ability of musicians [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Consequently, musicians are usually required to perform creative activities, such as improvisation while exhibiting virtuosity in free styles in various genres, including jazz and classical music. To this end, musicians must perform top–down regulation of sensorimotor synchronization. This prompts a question as to whether cognitive ability can enhance musical expertise.

The ASAP [

18] and GAE [

19] models, which enable the top–down regulation of sensorimotor synchronization via predictive coding of the premotor cortex, have been presented and used to demonstrate the musical skill of selecting meters from complex music rhythms [

20,

21]. However, these previous studies did not clarify the generalized claim that musical expertise could be improved by cognitive ability. Cognitive ability associated with creativity as craved by musicians is attributed to a concert of divergent and convergent thinking [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This would be linked to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), promoting self-referential processing [

27] and responsible for divergent thinking [

28], while the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is responsible for convergent thinking [

29,

30]. Further, creative thinking is accomplished via motor outcomes, regulated by the mPFC and presupplementary motor area (pre-SMA), part of the cortico-basal ganglia thalamo-cortical (CBGTC) motor control network [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The mPFC forms a default mode network (DMN) with the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), connected with the hippocampus [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and allows divergent thinking based on an episodic memory databank accumulated from experience. This divergent thinking shapes internal models.

The dACC integrates these intrinsic large-scale networks to guide actions achieving the required goal by resolving conflicts, selecting appropriate internal thoughts, making decision, and monitoring performance [

40,

41,

42]. Such role is supported by the finding that epinephrine levels in the brain are negatively correlated with the connectivity among large-scale intrinsic networks [

43].

Considering these previous data, we hypothesized that dACC could make flexible top-down regulation of sensorimotor synchronization in accordance with internal models. The current study aimed to show the validity of our hypothesis utilizing an appropriate task. We adopted the missing-oddball task in a conventional finger-tapping paradigm. This task adopted the uncertain sequence formed by randomly subtracting pulses form a normal sequence. Participants were asked to simultaneously tap with sound pulses as external auditory cues while restraining taps for missing pulses. Cued tapping, characterized by negative mean asynchrony [

44] and arising from auditory-tactile integration [

44], is dominant for normal sequences. Such control framework depends on the motor activity, which is proactively activated before the pulse presentation onset, supported by any functions of clocks synchronized with external cues. Such clock signals probably guide such predicting tapping to the goal where tactile sensation meets the pulse [

44,

45,

46]. In principle, such foreseeing strategy is not available for missing pulses. However, response delay compensates this shortcoming (

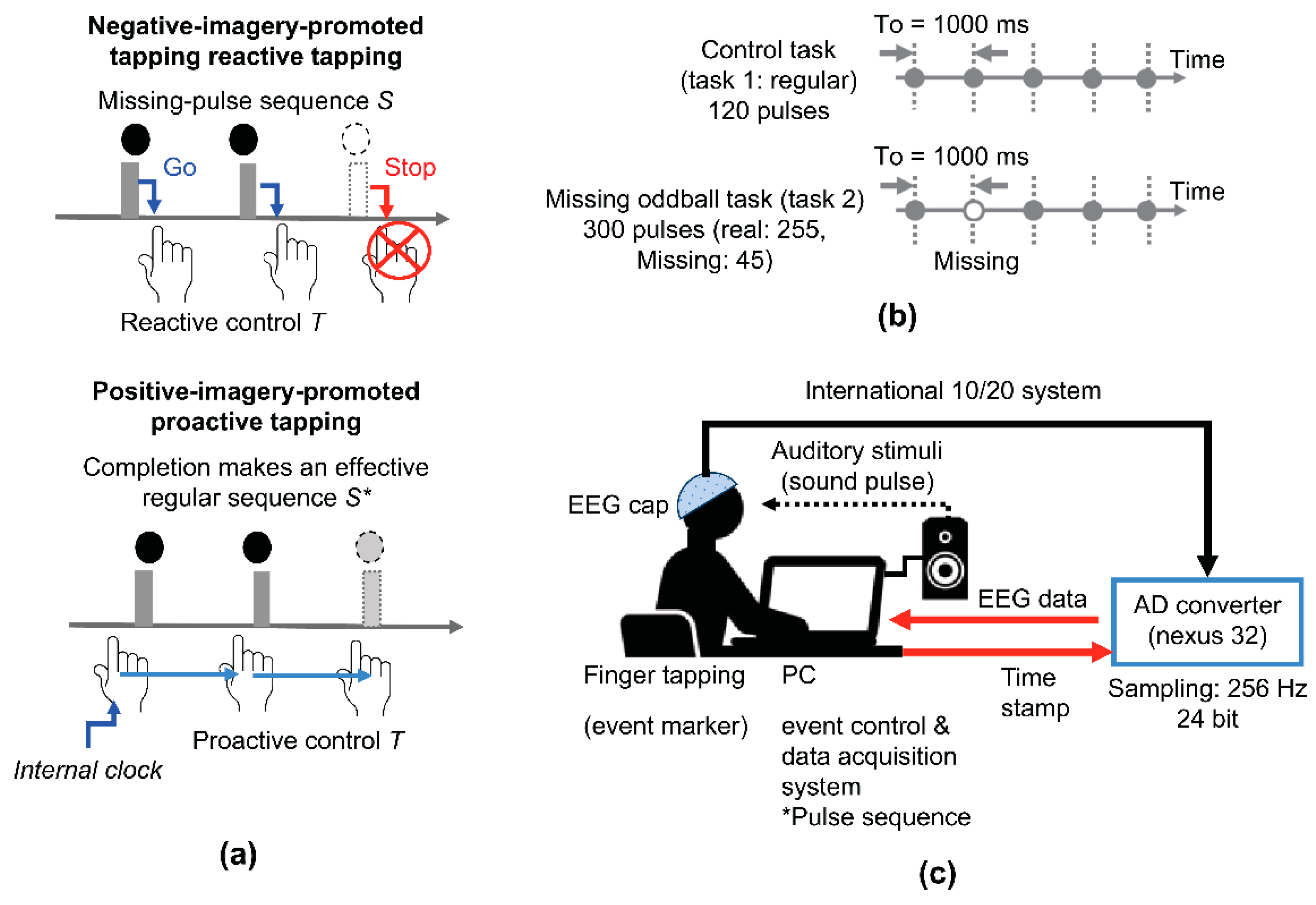

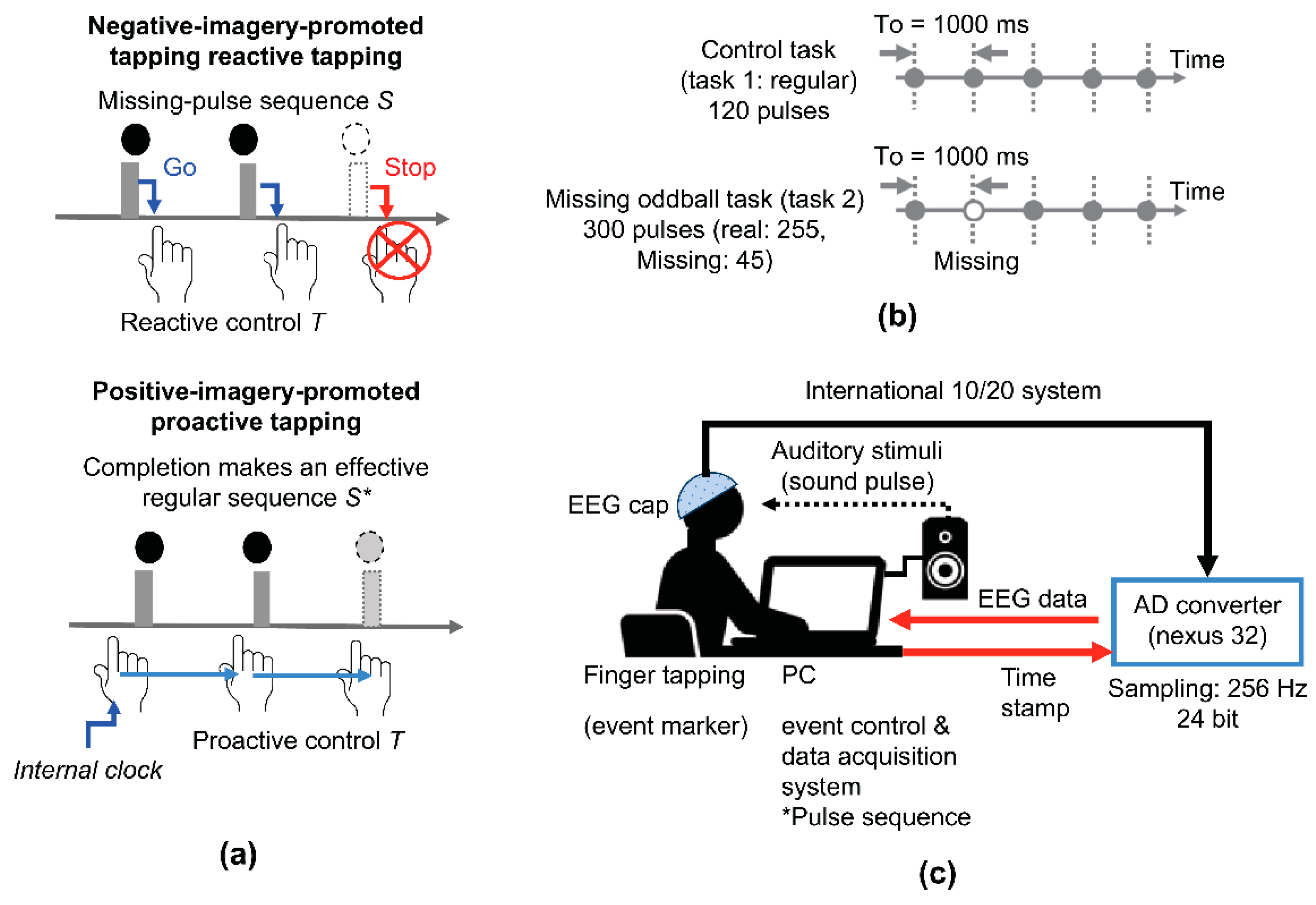

Figure 1a) as restraining tapping until expected pulse arrival time (Time 0) allows to select relevant responses for real or missing pulses. Such response-delay strategy for engaging missing pulses is supported by a previous study [

45] reporting that explicit stop cues embedded in a regular sequence induce proactive inhibition accompanied by response delay. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 1b, strong internal imagery of a regular beat with no missing pulses promotes filling in the blank. This makes participants to perform proactive responses accompanied by negative asynchrony. Therefore, the task can differentiate two types of internal models, i.e., regular and missing-pulse sequences, via tapping manners accompanied by negative and positive asynchronies, respectively.

We conducted the missing oddball task with music students and examined behavioral and brain responses during the task to elicit evidence for our hypothesis. Considering which internal models are dependent on the individual traits of musicians, we predicted that musicians who prefer to have a regular sequence would perform filling in the blank, whereas those who prefer to have a missing-pulse sequence would engage proactive inhibition accompanied by response delay to avoid the missing pulses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study protocol was approved by the board of Ethical Committee of Kobe University Graduate School of Health Sciences (Approval Number 1097). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. We recruited 14 healthy (no daily use of psychotropic drugs) volunteer student musicians (mean age 20.7 years, range 19–22) from the Graduate School of Music, Mukogawa Woman’s University, Japan. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. We included only females because in previous studies, sex differences in musical expertise were attributed to specific brain functions and structure [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51], particularly that females possess higher interhemispheric connectivity and thereby manifest higher sophistication than males [

52]. In contrast, males prefer more risk-taking behaviors than females [

53]. Hence, it is recommended to conduct research separating according to sex [

54].

2.2. Stimuli and Experimental Procedure

The stimuli consisted of sequence of pure-tone pulses (pitch: 1000 Hz, duration: 100 ms;

Figure 1c). Two tasks, differing in sequence, were provided for cued tapping experiments. Task 1adopted a regular sequence consisting of 120 pulses arranged with the same interval (1000 ms), while Task 2 adopted a missing-pulse sequence consisting of 45 missing (silent) pulses arranged by randomly omitting pulses from a regular sequence consisting of 300 pulses.

Figure 1d presents the stimuli and experimental setup. Participants were seated facing a lap-top computer on a desk while wearing an EEG cap. The computer presented auditory stimuli according to the provided sequence. All participants maintained their eyes closed while executing the cued tapping tasks. Further, they were asked not to move their heads or grind their teeth to suppress artifacts. Participants were asked to press a computer key simultaneously with stimulus presentation. Hence, the task with the missing-pulse sequence followed a conventional GO/NOGO paradigm in which prompt keystrokes were required for real pulses while any strokes are strictly prohibited for missing pulses regarded as erroneous tapping, while no keystrokes for real pulses were regarded as omission errors. All participants conducted the two tasks in a fixed order (Task 1 followed by Task 2). The time necessary for completing the tasks was ≤10 min including an intermission time of a few minutes. During tasks, participants were asked to keep their eyes closed. The EEG cap had preassembled Ag/AgCl electrodes consistent with the international 10–20 method, including mastoid electrodes (A1 and A2) as reference. The EEG signals from the cap were recorded by a digital (24-bit) EEG system (Nexus32, Mind Media BV, Netherland) at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. The EEG system was regulated by a control software (Biotrace+ Software for Nexus 32) installed in a computer. The system regulated sequential stimulus presentations and integrated EEG data with stimulus onset and tap times recorded in an event channel with a sampling rate of 512 Hz. To avoid electrical noise, a wireless keyboard, placed on a conductive sheet linked to the participants via an electrical cable for suppressing static electricity, was used to maintain complete electrical isolation of the EEG system, which was similarly linked to the PC via optical fiber cables.

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

2.3. Classification of Participants

We postulated that music students could be separated into two groups characterized by the type of imagery, i.e., positive and negative imagery, which arise from expectations for an incoming pulse and a missing pulse, respectively. This imagery difference could promote opposing behaviors; i.e., positive-imagery musicians (P-musicians) could maintain a proactive motor-control mode and fill in the blanks in the missing-pulse sequence, manifesting negative mean asynchronies, whereas negative-imagery musicians (N-musicians) could avoid erroneous tapping for the missing pulses but manifest avoidance failure accompanied by positive mean asynchronies. Hence, we classified the participants as P-musicians and N-musicians based on the mean reaction times of erroneous tapping for the missing pulses.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Performance Data

The reaction time was evaluated from pairs of stimulus onset and key-stroke markers in every epoch, ranging from −500 to 0 ms time-locked to the stimulus onset recorded in the event channel at a time resolution of 1.953125 ms, corresponding to a sampling rate of 512 Hz. The mean reaction times for every participant were classified according to stimulus conditions, i.e., real pulses in the regular sequence (Task 1), real pulses and missing pulses in the missing-pulse sequence (Task 2). After this classification, all analyses were based on comparisons between the two groups. We used the Mann–Whitney U test for evaluating group differences in reaction times at a significance level of 0.05.

To evaluate performance accuracy, omission errors were identified for real pulses without no tap marker while commission errors (erroneous tapping) were identified for any tap markers. Correlation between the rate of commission errors and the mean reaction time of erroneous tapping was evaluated using regression analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficient derived from the scatter plots of error rate versus mean reaction time, and the statistical significance was examined with an F-test. Significance level was set at 0.05. To examine whether tapping was attributed to proactive or reactive control, the distribution of reaction times was evaluated by the kernel density estimation (KDE) method using grand mean reaction times for N- and P-musicians.

2.4.2. ERP Waveform Data

As previously reported, simultaneous EEG-fMRI measurement is useful for studying brain dynamics [

55,

56,

57]. In the current study, we focused on endogenous ERP components including P100 and N200 for missing pulses, while recognizing conventional late auditory evoked potentials (LAEPs) including P50, N100, P200, N400, and the late positive complex (LPC) for real pulses. Generally, endogenous N200, originating at the mid cingulate cortex [

58] is generated by top-down attention [

59]. This component is associated with both response inhibition [

60] and emotional content [

61]. In our case, N200 was considered to accompany response inhibition against erroneous tapping. We could identify risk-hedge manners form N200. We also focused on the P150, considered to arise from the salience network including the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula [

62], is sensitive to absence of repeated stimuli, and associated with recognition of the part-whole configuration [

63,

64]. Hence, we used the P150 for distinguishing whether the risk-taking was driven by mistake or promoted by the part-whole configuration [

65]. Accordingly, we visually inspected ERP waveforms in defined time windows to detect P50, N100, P200, N400, and LPC for real pulses and for detecting P100, N200, P300, and N400 for missing pulses. The EEG signal at the vertex electrode (Cz) was pre-processed using a digital bandpass filter (third-order Bulterworth digital filter) with a 0.01–45 Hz window. The digital time-series data were similarly segmented from −1000 to 8000 ms around Time 0. After excluding deviant epochs by visual inspection, the remaining epochs were grand averaged to elicit the ERP waveforms for each condition, including stimulus type, tap performance, and participant type. The waveforms were baseline corrected by an average of the pre-stimulus epoch from −200 to 0 ms. The waveforms were time-locked to the stimulus onset. The ERP components were confirmed by a one-sample t-test. Group differences in ERPs were evaluated by the Sidak-holm test as a part of two-way ANOVA. All significance levels were set at 0.05.

2.4.3. Event-Related Deep-Brain Activity

Considering the flexible changing of behavioral manners from risk-taking and risk-hedge under the presence of missing pulses, we predicted that the dACC would change its activity according to every pulse/missing pulse stimulus. In fact, dACC activity can be evaluated from occipital EEG alpha-2 (10–13 Hz) power fluctuations with higher-frequency (> 0.1 Hz) components [

66]. We utilized this knowledge to evaluate the dynamics of the dACC and created the event-related deep-brain activity (ER-DBA) method [

67,

68].

Occipital EEG amplitude signals elicited from the O1 and O2 electrodes referred to the mastoid electors (A1 and A2) were filtered (third-order Bulterworth digital filter) to extract the alpha2-band component and smoothed by a moving average (Time window: 32.25 ms). We defined the DBA index as the mean actual power of these amplitude data. The mean power data were further segmented in epochs from −1000 to 8000 ms around the pulse/missing-pulse onset (Time 0). Deviant epochs were eliminated by visual inspection. Then, all epochs were grand averaged for stimulus type (real or missing), tap performance (relevant (avoid) or irrelevant (tap) for missing pulses), and participant type (e.g., N- or P-musicians). The grand-averaged ER-DBA waveforms were time-locked to stimulus onset. To evaluate behavioral (tap or avoid) differences, the ER-DBA waveforms for missing pulses were baseline corrected using the average of the upper and lower envelop of the ER-DBA waveform for real pulses in the missing pulse sequence. Each ER-DBA waveform was evaluated using the SEM. Further, baseline-corrected ER-DBA waveforms were evaluated to estimate dACC activity in each epoch of interest. As previously reported, the ER-DBA dynamics reflects the dACC activity associated with cognitive processing, e.g., local increase/decrease of the ER-DBA waveform indicates dACC access to external/internal information, while a dip in the ER-DBA waveform represents typical decision-making processing in the dACC. These interpretations are in line with conventional knowledge on alpha ERD/ERS addressing cognitive functions [

69,

70,

71] and motor execution [

72].

3. Results

3.1. Classification of Music Students into Positive- and Negative-Imagery Types

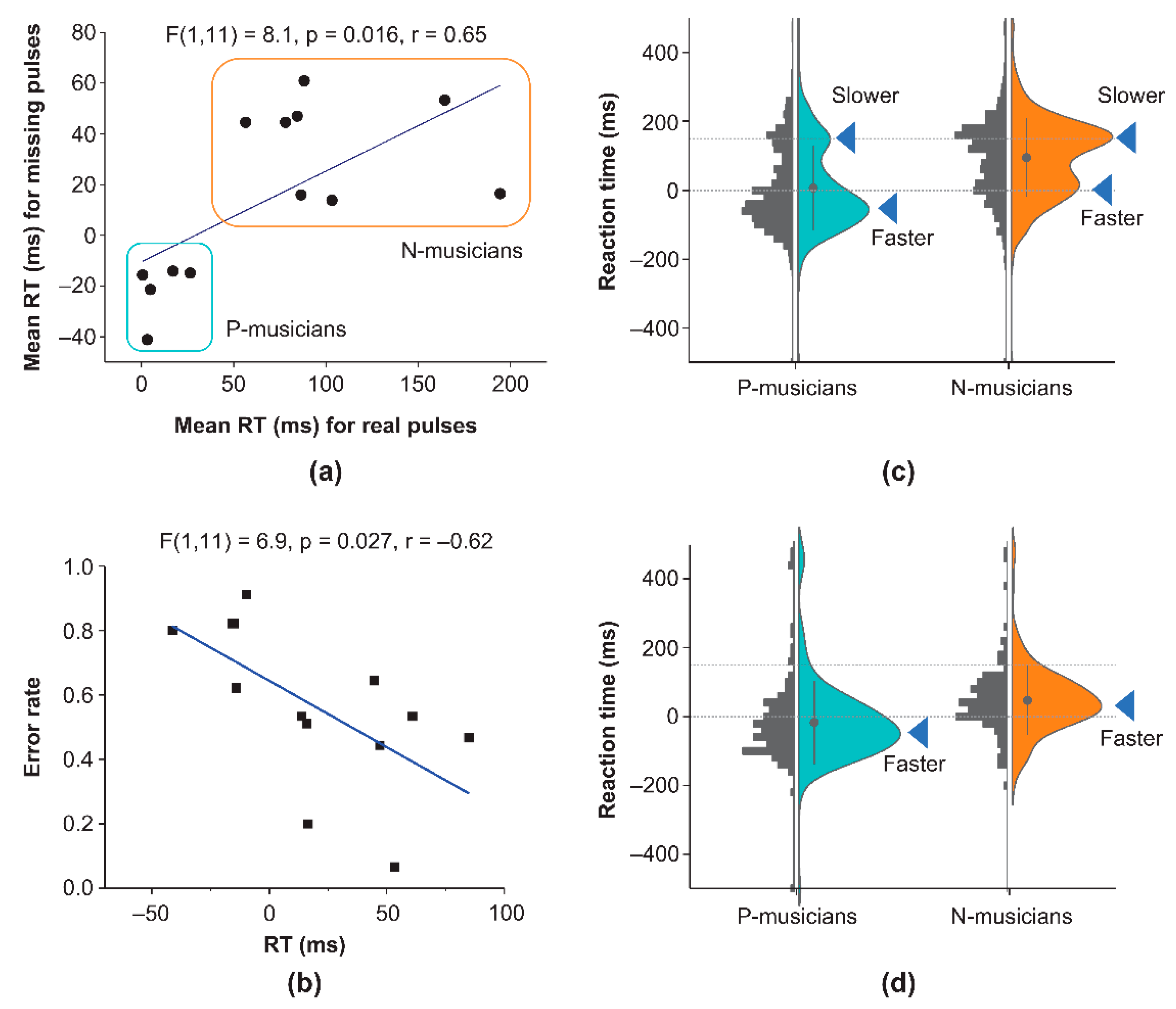

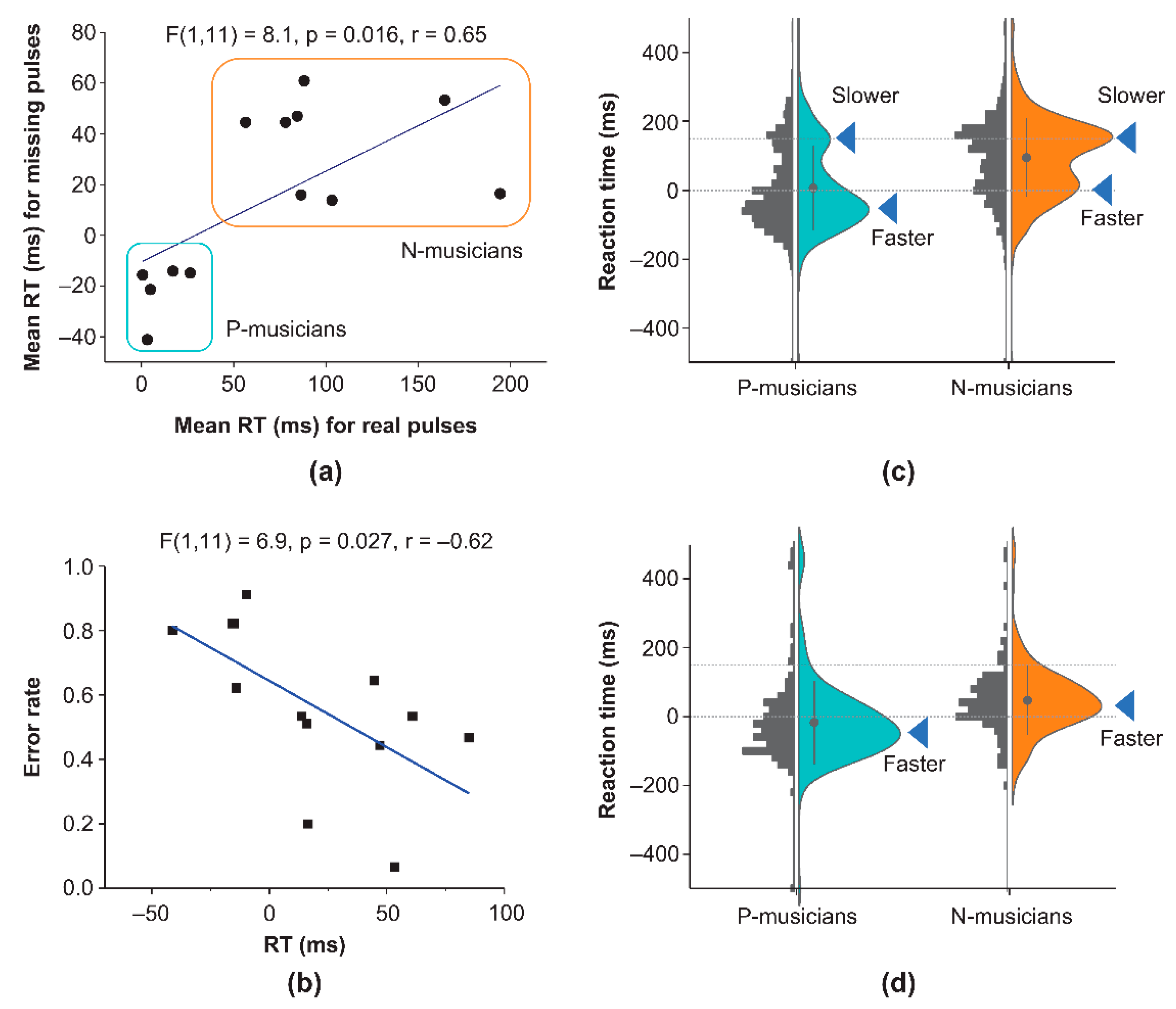

Figure 2a shows scatter plots of individual mean reaction times for real versus missing pulses in Task 2, providing positive linear correlation (F

(1,11) = 8.1, p0.016, r = 0.65).

First, we classified participants as P-musicians or N-musicians based on the classification criterion utilizing the aforementioned plots. We identified five P- and nine N-musicians.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of P- and N-musicians. There were no significant differences in music expertise between groups, although they exhibited small differences in onset age of music practice. Under this classification, we re-evaluated error rate versus response time for the missing pulses. As shown in

Figure 2b, we obtained a negative linear correlation (F

(1,11) = 6.9, p = 0.027, r = −0.62), which indicated that a response-delay strategy could be beneficial for N-musicians as the free-energy account predicted, while invalid for P-musicians.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.2. Behavioral Differences between Positive- and Negative-Imagery Types

We further examined group differences in reaction time distribution by the KDE method. As shown in

Figure 2c, both P- and N-musicians manifested double-lobe KDE curves for real pulses in Task 2, showing a common slower population peak at around 150 ms and negative and positive population peaks for P- and N-musicians, respectively. The critical time of 150 ms was attributed to the neural processing necessary for motor initiation triggered by the real-pulse stimulus [

73]. Hence, the slower responses at around the critical time could be promoted by reactive control. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 2d, P- and N-musicians showed single-lobe KDE curves but their population peaks differed: the peak was negative for P-musicians but positive for N-musicians.

All figures and tables should be cited in the main text as

Figure 1,

Table 1, etc.

3.3. Neurophysiological Differences between Positive- and Negative-Imagery Types

3.3.1. ERP data

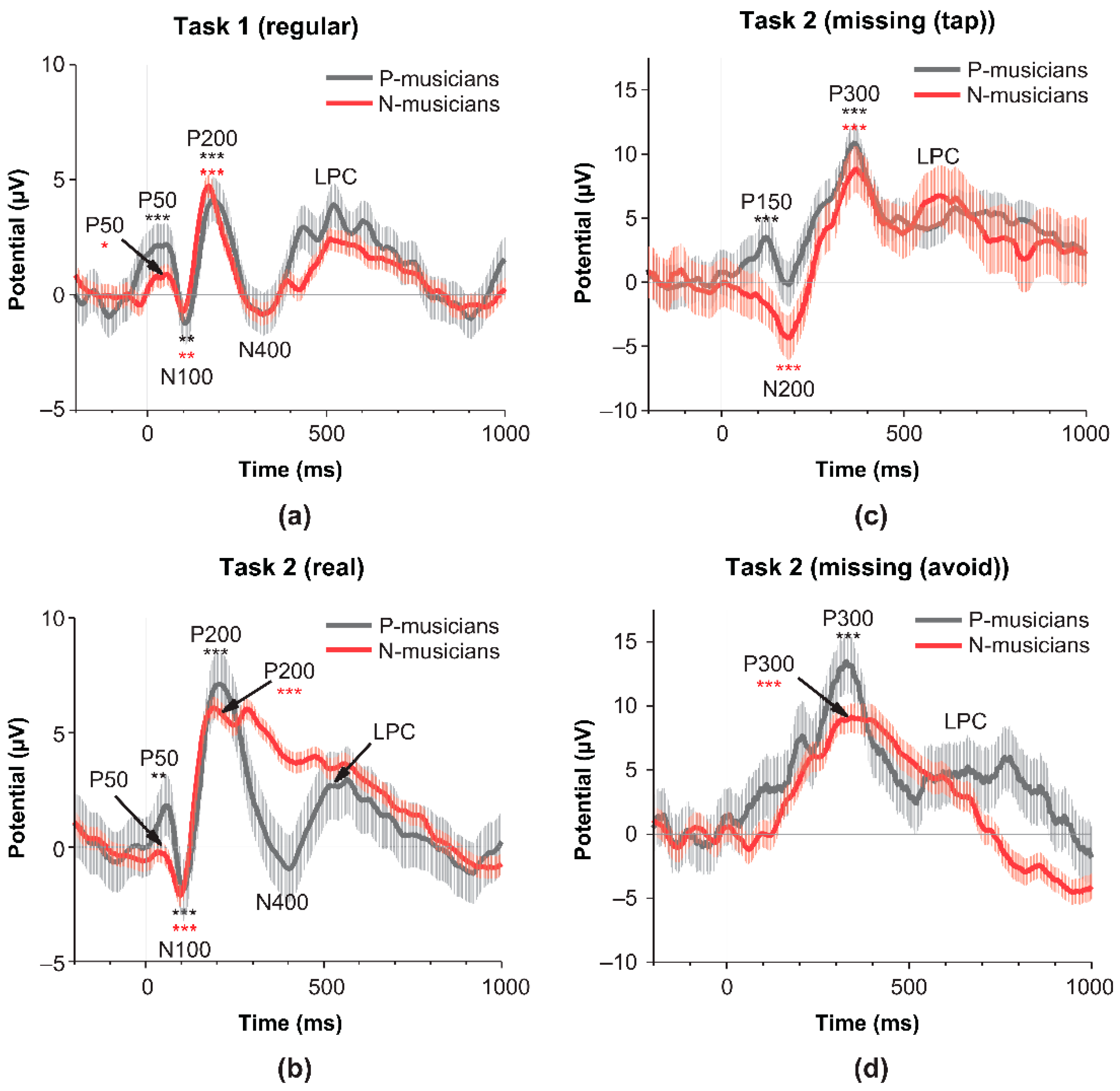

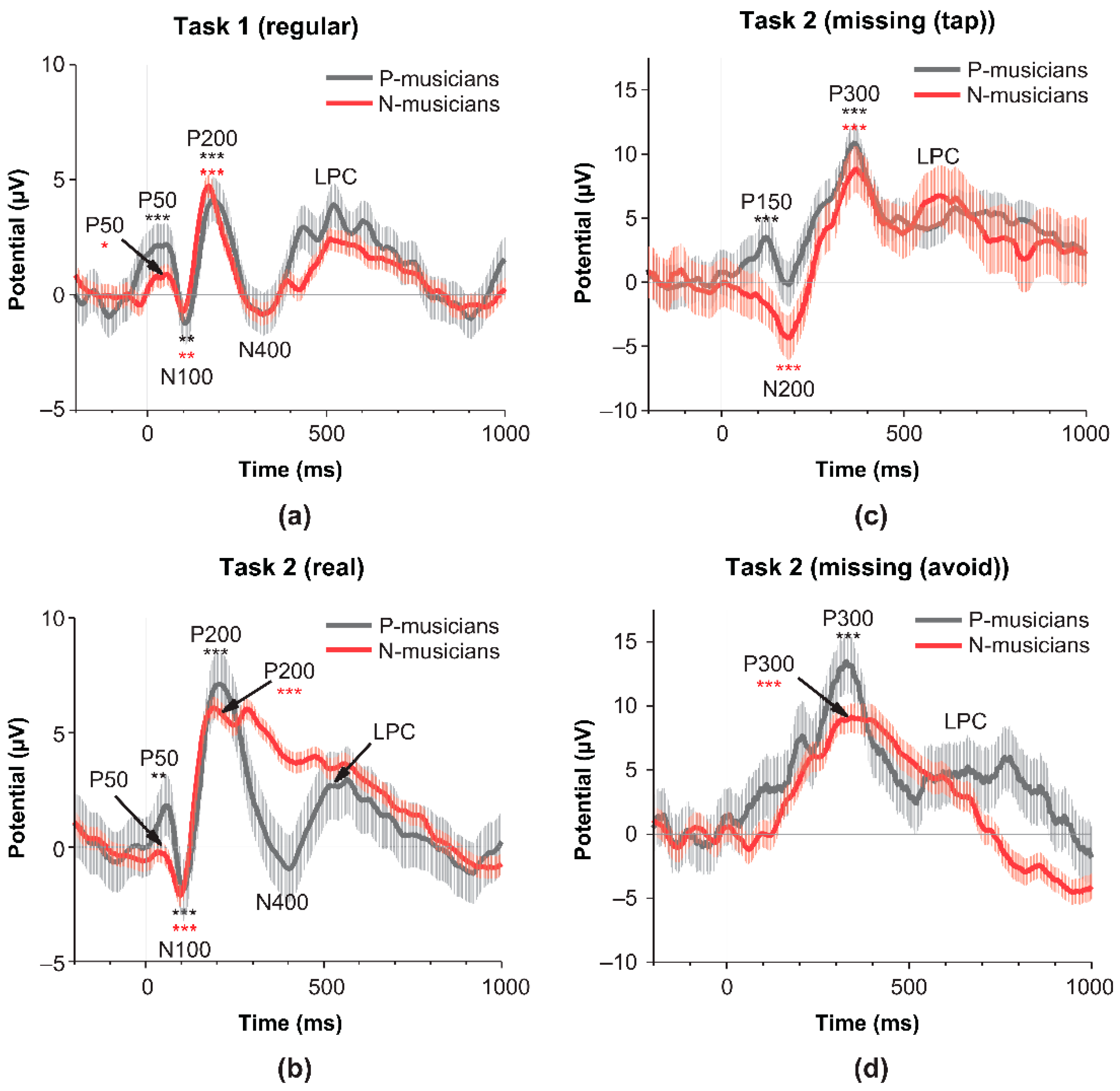

To test our neurophysiological predictions, we first analyzed ERP waveforms under Tasks 1 and 2.

Figure 3a shows the grand-averaged ERP waveforms for regular sequence (Task 1). The significant ERP waveforms (one-sample t-test) confirmed typical LAEPs including P50 (P-musician: p = 0.0001(Power = 0.97), N = 1985;N-musician: p = 0.015(0.64), N = 2661), N100 (P-musician: p = 0.0015(Power = 0.88), N = 1647;N-musician: p = 0.00017(0.96), N = 2661), P200 (P-musician: p =

(1.0), N = 1647;N-musician: p =

(1.0), N = 2661) and LPC (P-musician: p =

(Power = 1), N = 35685 ;N-musician: p =

(Power = 1), N = 57655) showed no significant differences between P- and N-musicians. In contrast, grand-averaged ERP waveforms for the regular parts of the missing-pulse sequence (Task 2) differed between P- and N-musicians (

Figure 3b), except for N100 (P-musician: p =

(Power = 0.89), N = 3705); N-musician: p =

(Power = 1.0), N = 5928) and P200 (P-musician: p =

(Power = 1.0), N = 3705); N-musician: p =

(Power = 1.0), N = 5928). P-musicians had clear P50 (p = 0.0027 (0.84), N = 3705) and N400 (not significant from baseline), while N-musicians closed P50 and N400. Further, we identified significant performance-dependent differences between P- and N-musicians during tapping for missing information (

Figure 3c). P-musicians had clear P150 (p =

(Power = 0.97), N = 414) and attenuated N200 (p = 00.61 (not significant) (0.08), N = 414), while N-musicians provided clear N200 (p = 0.000059 (0.98), N = 429) but closed P150. Despite the strong difference in ERP waveforms between P and N-musicians during tapping for the missing information, we identified no significant group differences in ERP waveforms for tapping avoidance of missing information (

Figure 3d). Both P- and N-musicians had similar P300 (P-musician: p =

(Power = 1.0), N = 219; N-musician: p =

(Power = 1.0), N = 585) in the avoidance responses for the missing information.

3.3.2. ER-DBA Data

We further examined brain responses during both Task 1 and 2 using the ER-DBA method.

Figure 4a indicates that both P- and N-musicians showed sinusoidal ER-DBA waveforms synchronized with real pulses in the regular portions of the missing-pulse sequence (blue lines in the figure) but different waveforms for the missing pulses (red lines). P- and N-musicians differed in their responses to the missing pulses in the pre-presentation epoch ranging from −500 to 0 ms (gray mask). P-musicians increased the ER-DBA waveform during taps for missing information but decreased during avoidant responses. In contrast, N-musicians manifested global inhibition in the ER-DBA waveform during the epoch of interest, although the waveform for avoidant responses was lower than that for taps. In addition, these brain responses of N-musicians for the missing information resulted in ER-DBA waveforms with dips just before the presentation onset (Time 0), suggesting that the motor control could change from reactive to proactive.

Figure 4b shows the significant differences in average power of the ER-DBA waveform in the epoch of interest ranging from −500 to 0 ms between P- (left panel) and N-musicians (right panel) obtained with the Sidak-holm for multiple tests after a one-way ANOVA.

These ER-DBA results were consistent with the third prediction that modal completion could be promoted by excitatory activity of the dACC while the aversive response could be promoted by inhibitory activity. We further evaluated the overall aspects of the sinusoidal ER-DBA waveform. Since dACC activity is supported mainly by dopamine released from the VTA, the amplitude of the waveform positively correlates with the medias. Hence, we evaluated these values as a function of reaction time of taps for missing cues as shown in

Figure 4c. The parabolic fitting for the scatter data was significant (F

(2,23) = 5.4, p = 0.011), suggesting that both modal completion and risk-aversion require mush cognitive load.

4. Discussion

4.1. P-musicians Perform Filling in the Blank Supported by Modal Completion, whereas N-musicians Maintain Reality

We found that P150 only appeared for filling-in the blanks (erroneous tapping for missing information) in P-musicians but not in N-musicians. We ascribed this potential to illusion by modal completion.

There are two possible explanations for the presence of the P150. One that P150 appears for rare stimuli in conventional auditory oddball task paradigms [

74] and could be exogenously generated by bottom-up processing in the sensory cortex. However, this hypothesis is based on only the empirical criterion that ERPs with latency <300 ms should be exogenous.

Neurophysiologically, modal completion is characterized by the endogenous event-related potential (ERP) component of P150, generated during cognitive processing of the part-whole configuration [

63,

64] as a kind of modal completion [

65]. Further, recent studies [Perri et al., 2019,62] have revealed that P150 is generated by illusion and sourced around the ACC. Hence, the emergence of this ERP suggests that the regular sequence as a whole can be reconstructed from the missing-pulse sequence partly by modal completion accompanied by auditory illusions.

Interestingly, we further found that N200 was attenuated during such modal completion accompanied by P150. The ERP component N200, arising from the midcingulate cortex [

58] is activated by top–down attention [

59] to inhibit responses [

60,

76,

77,

78]. Hence, the attenuation of N200 implies that top–down attention is prohibited during the occurrence of modal completion. This indicates that the brain can generate a coherent story to promote behaviors in accordance with internal models by deceiving the sensory cortex using illusions.

4.2. Role of the dACC in the Top–Down Modulation of Sensorimotor Synchronization

We observed opposing ER-DBA changes between tapping for the missing pulses, i.e., ER-DBA activation (ERS) for the tapping accompanied by clear P150 and ER-DBA deactivation (ERD) for the tapping accompanied by clear N200. This differentiation was considered to arise from differences in the internal model of predicting the pulse sequence, namely, ER-DBA activation and deactivation anticipate the appearance and absence of pulses, respectively. Hence, the findings suggest that the dACC regulates behaviors under sensorimotor synchronization in accordance with internal models.

As reported by Kim et al. [

79], the dACC has two subregions, caudal and rostral, suggesting that the caudal dACC engages in perceptual conflict while the rostral dACC engages in response conflict in the Stroop task. Accordingly, we considered that the caudal dACC may consider the missing-pulse sequence as a perceptual conflict arising from discrepancy between the external missing-pulse sequence and the regular sequence as an internal model and utilize behavioral adaptation by modal completion (filling-in the blanks). In contrast, the rostral dACC may regard the above adaptation as irrelevant against the task goal and aim to avoid such adaptive behavior. During the pre-stimulus epoch, participants face dual response options under uncertainty, i.e., response delay as a safe uncertainty-aversion option and a potential response like jackpot or bust [

80]. The strategy selected depends on participant traits: the P- musicians may select a potential response while N- musicians may select response delay.

Hence, P-musicians activate the caudal dACC (corresponding to ERS) for promoting the potential response characterized by negative asynchrony [

81]. Interestingly, such modal-completion-related behavioral adaptation may be associated with emotional reward as the rostral dACC is inactivated under dominant caudal dACC and thereby amygdala, positively correlated with orbitofrontal cortex [

82] and negatively correlated with rostral dACC [

83], is relatively activated. In contrast, N-musicians activate the rostral dACC (corresponding to ERD) to temporally suppress risky impulsive responses under uncertainty. To this end, the CBGTC motor control network along the striatal indirect pathway [

84]. The subthalamic nucleus (STN) is crucial for this inhibitory regulation [

85], and the SMA together with the inferior frontal gyrus [

86,

87] rather than working memory [

88] due to lack of explicit external stimuli in the pre-stimulus epoch, is responsible for producing stop signals for STN. Further, the SMA is regulated by the limbic system, notably the dACC [

89,

90].

Together, the dACC actively regulates motor outcomes along the indirect SMA-STN pathway.

4.3. Free Energy Accounts for Group Differences in Tapping Manners

Although the dACC regulates sensorimotor synchronization in accordance with internal models, the mechanism of decision making by the dACC remains unclear. Therefore, we will utilize the free energy principle (FEP) [

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103] to address this issue. According to the FEP, the free energy for representing the brain state is expressed for the tapping manner as

In this equation, S represents external sound states, where S = 1 and S = 0 correspond to the presence and absence of pulses, respectively. In addition, T represents behavioral states, where T = 1 and T = 0 correspond to tapping and avoidance, respectively. Further, Q(S) is a likelihood function for inferring the external state S. Hence,, the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence, represents the inference error between the inference Q(S) and external state S. For convenience, the first and second terms of Eq. (1) are named Bayesian and Shannon terms, respectively.

This FEP formalism gives the behavioral criterion by which the brain regulates executive manners to minimize the free energy. This FEP framework can simply explain the complex behavioral manners manifesting opposing responses for the missing pulses as follows.

For P-musicians, when the internal model expects a pulse to be present [Q(S) = Q(1)], the Bayesian term increases with discrepancy between the internal model as Q(1) and the real-world state, namely the missing S = 0. However, the brain deceives the sensory cortex via modal completion as S = 1 utilizing modal completion accompanied by auditory illusions. Hence, the Bayesian term as the inference error is minimized to zero. Further, tapping for the missing pulse is regarded as normal activity for regular sequences; thus, the Shannon term is also minimized to zero. This FEP framework is regarded as a type of active inference. Considering that the caudal and rostral dACC are responsible for perception and response conflicts, respectively, we consider that the caudal dACC might promote tapping by deceiving sensory evidence and suppressing the rostral dACC, which is responsible for inhibiting irrational behaviors, including erroneous tapping for the missing pulses. This view is consistent with role of the dACC in the top–down regulation of sensorimotor synchronization, as evidenced by our findings.

Conversely, for N-musicians, when the internal model expects a missing pulse [Q(S) = Q(0)], there is no inference error for the missing S = 0. Thus, the free energy is minimized when the brain selects avoidance (T = 0) as a relevant response. N-musicians appeared to have such an internal model, but it provided erroneous tapping. We considered that such erroneous manners of N-musicians might be attributable to the strength of confidence in internal models and statistical evaluation of the missing pulse based on the Bayesian inference using the posterior probability. Underestimation of the missing pulse might reduce the confidence in the missing pulse, and thus, the inference might become Q(1), resulting in the emergence of erroneous tapping.

This view suggests that all erroneous tapping is promoted by proactive control accompanied by negative asynchrony based on top–down regulation by the rostral dACC. This is consistent with the results. Furthermore, halfway confidence for the presence of absence of pulses under uncertainty might provide a probabilistic choice of behaviors. Hence, even for real pulses, the tapping is a mixture of negative and positive asynchronies corresponding to proactive and reactive motor control modes, respectively. This is also consistent with the results. Interestingly, P-musicians tended to maintain negative asynchrony, suggesting that they have strong confidence in the internal model of pulse presence.

Consequently, differences in musicians’ traits might be attributable to their internal models. The dACC might support their wills in accordance with their own models.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex can regulate motor behaviors promoted by sensorimotor synchronization in accordance with internal models. This top–down regulation is supported by abilities of the brain typically including modal completion accompanied by illusions to create a coherent story, thereby allowing internal models to be consistent with sensory evidence. This function of the dACC will improve cognitively controllable movements, thereby helping to foster skills, such as music expertise.

Despite the validity of such beneficial functions of dACC, several issues remain to be resolved. A typical issue is the mechanism by which internal models are promptly updated under a rapidly changing environment, suggesting that statistical learning would be impeded. If higher confidence is imposed on internal models, then it will be difficult to promptly update these models. Conversely, if internal models are easily updated with environmental changes, then it will be difficult to promote proactive motor control, suggesting that skilled motor control will be impeded. Hence, it is necessary to solve this discrepancy in future studies.

Author Contributions

M.U. was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, and original draft writing. Y.K. contributed significantly to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology development, validation, visualization, original draft writing, review, editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. E.I. focused on conceptualization, methodology, and review and editing. T.I. worked on conceptualization, resource management, and review and editing. K.K. contributed to conceptualization and resource management. Lastly, H.K. oversaw conceptualization, supervision, project administration, and contributed to the review and editing stages.

Funding

This research was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 19K04921).

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, they were briefed on the abstract of the study and instructed to secure the right as a volunteer to withdraw any time without any disadvantages. The study protocol was approved by Ethical committee of Kobe University Graduate School of Health Sciences (No.1097).

Informed Consent Statement

After brief instruction, they all participants gave written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor Hiromi Ozaku of Kobe University Graduate School of Health Science Japan for her heartful support for promoting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Goebl, W.; Palmer, C. Synchronization of timing and motion among performing musicians. Music Percept. 2009, 26, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, J.C.; Satyal, M.K.; Rugh, R. Dance on the brain: enhancing intra- and inter-brain synchrony. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 584312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.J.; Kong, Y.Z.; Hu, L. Enhanced neural synchrony associated with long-term ballroom dance training. Neuroimage 2023, 278, 120301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen et al.

- Bisio, A.; Faelli, E.; Pelosin, E.; Carrara, G.; Ferrando, V.; Avanzino, L.; Ruggeri, P. Evaluation of explicit motor timing ability in young tennis players. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 687302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kijima, A.; Kadota, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Okumura, M.; Suzuki, H.; Schmidt, R.C.; Yamamoto, Y. Switching dynamics in an interpersonal competition brings about "deadlock" synchronization of players. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e47911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repp, B.H.; Su, Y.H. Sensorimotor synchronization: a review of recent research (2006-2012). Psychon Bull Rev 2013, 20, 403–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirvonen, J.; Monto, S.; Wang, S.H.; Palva, J.M.; Palva, S. Dynamic large-scale network synchronization from perception to action. Netw. Neurosci. 2018, 2, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuust, P.; Witek, M.A. Rhythmic complexity and predictive coding: a novel approach to modeling rhythm and meter perception in music. Front Psychol 2014, 5, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, N.C.; Reymore, L. Articulatory motor planning and timbral idiosyncrasies as underlying mechanisms of instrument-specific absolute pitch in expert musicians. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, S.; Klein, C.; Jäncke, L. Musical expertise shapes functional and structural brain networks independent of absolute pitch ability. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2496–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichko, P.; Kim, J.C.; Large, E.W. A dynamical, radically embodied, and ecological theory of rhythm development. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 653696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Large, E.W.; Herrera, J.A.; Velasco, M.J. Neural networks for beat perception in musical rhythm. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; Fang, L.; Liu, G. Sustained effect of music training on the enhancement of executive function in preschool children. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwer, F.L.; Werner, C.M.; Knetemann, M.; Honing, H. Disentangling beat perception from sequential learning and examining the influence of attention and musical abilities on ERP responses to rhythm. Neuropsychologia 2016, 85, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischen, U.; Schwarzer, G.; Degé, F. Comparing the effects of rhythm-based music training and pitch-based music training on executive functions in preschoolers. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miendlarzewska, E.A.; Trost, W.J. How musical training affects cognitive development: rhythm, reward and other modulating variables. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Iversen, J.R. The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: the action simulation for auditory prediction (ASAP) hypothesis. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, H.; Honing, H. Are non-human primates capable of rhythmic entrainment? Evidence for the gradual audiomotor evolution hypothesis. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.E.; Wilson, D.A.; Radman, T.; Scharfman, H.; Lakatos, P. Dynamics of active sensing and perceptual selection. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, I.; Large, E.W.; Rabinovitch, E.; Wei, Y.; Schroeder, C.E.; Poeppel, D.; Golumbic, E.Z. Neural entrainment to the beat: the “missing-pulse” phenomenon. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 6331–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Kenett, Y.N.; Christensen, A.P.; Rosenberg, M.D.; Benedek, M.; Chen, Q.; Fink, A.; Qiu, J.; Kwapil, T.R.; Kane, M.J.; Silvia, P.J. Robust prediction of individual creative ability from brain functional connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2018, 115, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, A.; Beaty, R.; Lam, J.; Spreng, R.N.; Turner, G.R. Intrinsic default-executive coupling of the creative aging brain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2019, 14, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, H.; Taki, Y.; Nouchi, R.; Yokoyama, R.; Kotozaki, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Sekiguchi, A.; Iizuka, K.; Hanawa, S.; Araki, T.; Miyauchi, C.M.; Sakaki, K.; Sassa, Y.; Nozawa, T.; Ikeda, S.; Yokota, S.; Magistro, D.; Kawashima, R. Originality of divergent thinking is associated with working memory-related brain activity: evidence from a large sample study. Neuroimage 2020, 216, 116825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmiero, M.; Fusi, G.; Crepaldi, M.; Borsa, V.M.; Rusconi, M.L. Divergent thinking and the core executive functions: a state-of-the-art review. Cogn. Process 2022, 23, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vink, I.C.; Willemsen, R.H.; Lazonder, A.W.; Kroesbergen, E.H. Creativity in mathematics performance: the role of divergent and convergent thinking. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, e12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallwood, J.; Bernhardt, B.C.; Leech, R.; Bzdok, D.; Jefferies, E.; Margulies, D.S. The default mode network in cognition: a topographical perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raij, T.T.; Riekki, T.J.J. Dorsomedial prefontal cortex supports spontaneous thinking per se. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 3277–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, J.; Sampedro, A.; Balboa-Bandeira, Y.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Zubiaurre-Elorza, L.; García-Guerrero, M.A.; Ojeda, N. Comparing transcranial direct current stimulation and transcranial random noise stimulation over left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and left inferior frontal gyrus: effects on divergent and convergent thinking. Front Hum Neurosci 2022, 16, 997445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Luo, J.; An, Y.; Xia, T. tDCS anodal stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex improves creative performance in real-world problem solving. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.L.; de Manzano, Ö.; Fransson, P.; Eriksson, H.; Ullén, F. Connecting to create: expertise in musical improvisation is associated with increased functional connectivity between premotor and prefrontal areas. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6156–6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanese, J.; Jaeger, D. Premotor ramping of thalamic neuronal activity is modulated by nigral inputs and contributes to control the timing of action release. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Moberg, S.; Zolnik, T.A.; Catanese, J.; Sachdev, R.N.S.; Larkum, M.E.; Jaeger, D. Thalamic input to motor cortex facilitates goal-directed action initiation. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 4148–4155.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logiaco, L.; Abbott, L.F.; Escola, S. Thalamic control of cortical dynamics in a model of flexible motor sequencing. Cell. Rep. 2021, 35, 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Taki, Y.; Hashizume, H.; Sassa, Y.; Nagase, T.; Nouchi, R.; Kawashima, R. The association between resting functional connectivity and creativity. Cereb. Cortex 2012, 22, 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayseless, N.; Eran, A.; Shamay-Tsoory, S.G. Generating original ideas: the neural underpinning of originality. Neuroimage 2015, 116, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madore, K.P.; Thakral, P.P.; Beaty, R.E.; Addis, D.R.; Schacter, D.L. Neural mechanisms of episodic retrieval support divergent creative thinking. Cereb. Cortex 2019, 29, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, O.Y.; de Souza Silva, M.A.; Yang, Y.M.; Huston, J.P. The medial prefrontal cortex - hippocampus circuit that integrates information of object, place and time to construct episodic memory in rodents: behavioral, anatomical and neurochemical properties. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 113, 373–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, C.H.; Jütten, K.; Forster, S.D.; Clusmann, H.; Mainz, V. Self-referential processing and resting-state functional MRI connectivity of cortical midline structures in glioma patients. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, G.; Vogt, B.A.; Holmes, J.; Dale, A.M.; Greve, D.; Jenike, M.A.; Rosen, B.R. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a role in reward-based decision making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2002, 99, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.P.; Bédard, A.V.; Czarnecki, R.; Fan, J. Preparatory activity and connectivity in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex for cognitive control. Neuroimage 2011, 57, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, B.Y.; Platt, M.L. Neurons in anterior cingulate cortex multiplex information about reward and action. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3339–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, K.M. Possible brain mechanisms of creativity. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.C.; Reed, C.M.; Braida, L.D. Integration of auditory and vibrotactile stimuli: effects of phase and stimulus-onset asynchrony. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 126, 1960–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Meneses, L.J.; Sowman, P.F. Stop signals delay synchrony more for finger tapping than vocalization: a dual modality study of rhythmic synchronization in the stop signal task. Peer J. 2018, 6, e5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauzon, A.P.; Russo, F.A.; Harris, L.R. The influence of rhythm on detection of auditory and vibrotactile asynchrony. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, J.S. Sex and cognition: gender and cognitive functions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 38, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingalhalikar, M.; Smith, A.; Parker, D.; Satterthwaite, T.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Ruparel, K.; Hakonarson, H.; Gur, R.E.; Gur, R.C.; Verma, R. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2014, 111, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabinejad, M.M.; Rafei, P.; Sanjari Moghaddam, H.; Sinaeifar, Z.; Aarabi, M.H. Sex differences are reflected in microstructural white matter alterations of musical sophistication: A diffusion MRI study. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 622053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, S.A.; Miranda, R.A.; Ullman, M.T. Sex differences in music: A female advantage at recognizing familiar melodies. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoli, E.; Hildebrandt, H.; Gomez, P. Classical music students’ pre-performance anxiety, catastrophizing, and bodily complaints vary by age, gender, and instrument and predict self-rated performance quality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 905680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Schlaug, G. Corpus callosum: musician and gender effects. Neuroreport. 2003, 14, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.; Du, X.; Dong, G.H. Sex differences in neural substrates of risk taking: implicationsImplications for sex-specific vulnerabilities to internet gaming disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 2022. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 2022. 11, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, R.; Camfield, D.A.; Nield, G.; Stough, C. Gender differences in parieto-frontal brain functional connectivity correlates of creativity. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diukova, A.; Ware, J.; Smith, J.E.; Evans, C.J.; Murphy, K.; Rogers, P.J.; Wise, R.G. Separating neural and vascular effects of caffeine using simultaneous EEG-FMRI: differential effects of caffeine on cognitive and sensorimotor brain responses. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulert, C. Simultaneous EEG and fMRI: towards the characterization of structure and dynamics of brain networks. Dial. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 15, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Saharkhiz, S.; Rajabion, L.; Oskouei, H.B.; Seraji, M.; Fayaz, F.; Saliminia, S.; Sadjadi, S.M.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Simultaneous electroencephalography-functional magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of human brain function. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 934266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodo, E.; Kayama, Y. Relation of a negative ERP component to response inhibition in a Go/No-go task. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1992, 82, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzoni, A.; Di Russo, F.; Fabbri, S.; Pesaresi, I.; Di Rollo, A.; Perri, R.L.; Barloscio, D.; Bocci, T.; Cosottini, M.; Sartucci, F. "Hit the missing stimulus”. A simultaneous EEG-fMRI study to localize the generators of endogenous ERPs in an omitted target paradigm. Sci. Rep. 2019; 9, 3684. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, M.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Woo, S.I. Age-related in auditory nogo-N200 latency in medication-naïve children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaitkevičius, A.; Kaubrys, G.; Audronytė, E. Distinctive effect of donepezil treatment on P300 and N200 subcomponents of auditory event-related evoked potentials in Alzheimer disease patients. Distinctive Med. Sci. Monitor. 2015, 21, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Liang, W.; Xie, D.; Bi, S.; Chou, C.H. EEG features of evoked tactile sensation: two cases study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 904216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, A.; Thoma, V.; de Fockert, J.W.; Richardson-Klavehn, A. Event-related potential effects of object repetition depend on attention and part-whole configuration. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercillo, T.; Burr, D.; Gori, M. Early visual deprivation severely compromises the auditory sense of space in congenitally blind children. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanay, B. Amodal completion and relationalism. Philos. Stud. 2022, 179, 2537–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, K.; Hanakawa, T.; Morimoto, M.; Honda, M. Spontaneous slow fluctuation of EEG alpha rhythm reflects activity in deep-brain structures: A simultaneous EEG-fMRI study. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e66869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, E.; Katagiri, Y. Cognitive control and brain network dynamics during word generation tasks predicted using a novel event-related deep brain activity method. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2018, 08, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, A. Imai, E.; Katagiri, Y. Role of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in relational memory formation: A deep brain activity index study. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2018; 8, 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wianda, E.; Ross, B. The roles of alpha oscillation in working memory retention. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrijevic, A.; Smith, M.L.; Kadis, D.S.; Moore, D. R. . Cortical alpha oscillations predict speech intelligibility. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhozhikashvili, N.; Zakharov, I.; Ismatullina, V.; Feklicheva, I.; Malykh, S.; Arsalidou, M. Parietal alpha oscillations: cognitive load and mental toughness. Brain Sci 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rektor, I.; Sochůrková, D.; Bocková, M. Intracerebral ERD/ERS in voluntary movement and in cognitive visuomotor task. Prog. Brain Res. 2006, 159, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hatsopoulos, N.G.; Xu, Q.; Amit, Y. Encoding of movement fragments in the motor cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5105–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashima, M.; Nagasawa, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Oka, T.; Sakai, N.; Tsukada, T.; Komai, Y.; Koshino, Y. Event-related potentials elicited by non-target tones in an auditory oddball paradigm in schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2004, 51, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri et al.

- Huster, R.J.; Westerhausen, R.; Pantev, C.; Konrad, C. The role of the cingulate cortex as neural generator of the N200 and P300 in a tactile response inhibition task. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010, 31, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, J.R.; van Petten, C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattia, M.; Spadacenta, S.; Pavone, L.; Quarato, P.; Esposito, V.; Sparano, A.; Sebastiano, F.; Di Gennaro, G.; Morace, R.; Cantore, G.; Mirabella, G. Stop-event-related potentials from intracranial electrodes reveal a key role of premotor and motor cortices in stopping ongoing movements. Front. Neuroeng. 2012, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Kroger, J.K.; Kim, J. A functional dissociation of conflict processing within anterior cingulate cortex. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, M.L.; Huettel, S.A. Risky business: the neuroeconomics of decision making under uncertainty. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, V.; Rosati, A.G.; Taren, A.A.; Huettel, S.A. Resolving response, decision, and strategic control: evidence for a functional topography in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 13158–13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenberg, N.T.; Sepe-Forrest, L.; Pennington, Z.T.; Lamparelli, A.C.; Greenfield, V.Y.; Wassum, K.M. The medial orbitofrontal cortex–basolateral amygdala circuit regulates the influence of reward cues on adaptive behavior and choice. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 7267–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, K.L.; Avery, J.A.; Barcalow, J.C.; Moseman, S.E.; Bodurka, J.; Bellgowan, P.S.; Simmons, W.K. Trait impulsivity is related to ventral ACC and amygdala activity during primary reward anticipation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettine, W.W.; Louie, K.; Murray, J.D.; Wang, X.J. Excitatory-inhibitory tone shapes decision strategies in a hierarchical neural network model of multi-attribute choice. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.R.; Poldrack, R.A. Cortical and subcortical contributions to stop signal response inhibition: role of the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 2424–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachev, P.; Kennard, C.; Husain, M. Functional role of the supplementary and pre-supplementary motor areas. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, A.R.; Herz, D.M.; Brown, P.; Forstmann, B.U.; Zaghloul, K. Frontosubthalamic circuits for control of action and cognition. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 11489–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duann, J.R.; Ide, J.S.; Luo, X.; Li, C.S. Functional connectivity delineates distinct roles of the inferior frontal cortex and presupplementary motor area in stop signal inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10171–10179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asemi, A.; Ramaseshan, K.; Burgess, A.; Diwadkar, V.A.; Bressler, S.L. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex modulates supplementary motor area in coordinated unimanual motor behavior. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwadkar, V.A.; Asemi, A.; Burgess, A.; Chowdury, A.; Bressler, S.L. Potentiation of motor sub-networks for motor control but not working memory: interaction of dACC and SMA revealed by resting-state directed functional connectivity. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0172531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Janzen, T.; Thompson, W.F.; Ammirante, P.; Ranvaud, R. Timing skills and expertise: discrete and continuous timed movements among musicians and athletes. Front. psychol. 2014, 23, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.C. , Chou, T.L., Chen, H.C., Liang, K.C. Segregating the comprehension and elaboration processing of verbal jokes: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2012, 61, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.C. , Zeitlen, D.C., and& Beaty, R.E.. Amygdala-frontoparietal effective connectivity in creativity and humor processing. Hum. Brain Mapp., 2023, 44, 2585–2606. [Google Scholar]

- Huettel, S.A. Event-related fMRI in cognition. Neuroimage, 2012, 62, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.J. Auditory neuroscience: filling in the gaps. Curr. Biol., 2007, 17, R799–R801.801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Large, E.W. , Snyder, J.S. Pulse and meter as neural resonance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2009, 1169, 46-57.

- Nusseck, M. , Zander, M., Spahn, C. Music performance anxiety in young musicians: comparison of playing classical or popular music. Med. Probl. Perform. Art 2015, 30,(1), 30-37.

- Riecke, L. , Van Orstal, A.J., Formisano, E. The auditory continuity illusion: a parametric investigation and filter model. Percept. Psychophys.,2008, 70, 1-12.

- 100. Rossana, & Dalmonte. Towards a Semiology of Humour in Music. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 1995, 26, 167-187.

- SHANNON, C. E. A mathematical theoryMathematical Theory of communication.Communication. The Bell Syst. Tech. J.System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379-–423.

- Su, J. , Jia, W., Wan, X. Task-specific neural representations Specific Neural Representations of generalizable metacognitive control signals Generalizable Metacognitive Control Signals in the human dorsal anterior cingulate cortex.Human Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex. J. Neurosci 2022, 42,(7), 1275-1291.

- Wassum, K. M. (2022). Amygdala-cortical collaboration in reward learning and decision making. Elife, 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Outline of the experiments. (a) Behavioral strategy and performance in the missing-pulse oddball task. A response delay for judging real/missing pulses is an efficient strategy to avoid erroneous tapping (upper panel). Modal completion fills in the blank (missing site) with the illusion. This consequently maintains regular tapping with negative asynchrony (lower panel). (b) Normal and missing-pulse sequences. The normal sequence consisted of 120 pulses with an interval of 1000 ms, whereas the missing-pulse sequence consisted of 255 real pulses and 45 missing pulses formed by randomly omitting real pulses from a regular sequence with 300 occurrences. All real pulses had a pure tone of 1000 Hz with a duration of 100 ms. (b): Frequency of segment appearance versus number of real pulses involved in segments separated by missing pulses during task trials in the missing-pulse task. (c) Experimental setup. Participants sat at a table, and they were asked to simultaneously press a key with sound pulses with their eyes closed. The pulses were sequentially presented by a PC in accordance with the sequences for the tasks. A digital EEG system (Nexus 32, Mind Media BV, Herten, Netherlands) comprised an EEG cap with preassembled Ag/AgCl electrodes, consistent with the international 10–20 method, was used for EEG recordings. Data (sampling rate: 256 Hz, amplitude resolution: 24 bit) were acquired by a PC running control software (Biotrace) to integrate EEG data and event markers corresponding to tap timings.

Figure 1.

Outline of the experiments. (a) Behavioral strategy and performance in the missing-pulse oddball task. A response delay for judging real/missing pulses is an efficient strategy to avoid erroneous tapping (upper panel). Modal completion fills in the blank (missing site) with the illusion. This consequently maintains regular tapping with negative asynchrony (lower panel). (b) Normal and missing-pulse sequences. The normal sequence consisted of 120 pulses with an interval of 1000 ms, whereas the missing-pulse sequence consisted of 255 real pulses and 45 missing pulses formed by randomly omitting real pulses from a regular sequence with 300 occurrences. All real pulses had a pure tone of 1000 Hz with a duration of 100 ms. (b): Frequency of segment appearance versus number of real pulses involved in segments separated by missing pulses during task trials in the missing-pulse task. (c) Experimental setup. Participants sat at a table, and they were asked to simultaneously press a key with sound pulses with their eyes closed. The pulses were sequentially presented by a PC in accordance with the sequences for the tasks. A digital EEG system (Nexus 32, Mind Media BV, Herten, Netherlands) comprised an EEG cap with preassembled Ag/AgCl electrodes, consistent with the international 10–20 method, was used for EEG recordings. Data (sampling rate: 256 Hz, amplitude resolution: 24 bit) were acquired by a PC running control software (Biotrace) to integrate EEG data and event markers corresponding to tap timings.

Figure 2.

Tapping behavior during the missing-pulse oddball task (a) Scattered plots of individual mean reaction times for real-pulse taps versus missing-pulse taps during Task 2 (missing-pulse oddball task). A negative linear correlation (F(1,11) = 8.1, p = 0.016, r = 0.65) was obtained. The classification was based on the reaction time for missing pulses of 0 ms (corresponding to the time onset of missing pulses) in five S-musicians and eight B-musicians. (b) Scattered plot of error rates versus mean reaction times revealing a linear negative correlation (F(1,11) = 6.9, p = 0.027, r = −0.62). (c) Kernel density estimation (KDE) curves accompanied with histograms for the reaction times of all taps for real pulses separately depicted for S-musicians (curiosity type) and B-musicians (risk-aversion type). The curves indicate dual (faster and slower) populations marked by triangles. Notably, the peak time of approximately 150 ms for the faster populations was common for both S- and B-musicians, whereas that for the slower populations differed. (d) Similar KDE curves as in C for taps for missing pulses. The curves depicted a single-lobe population for both S- and B-musicians. r: Pearson correlation coefficient.

Figure 2.

Tapping behavior during the missing-pulse oddball task (a) Scattered plots of individual mean reaction times for real-pulse taps versus missing-pulse taps during Task 2 (missing-pulse oddball task). A negative linear correlation (F(1,11) = 8.1, p = 0.016, r = 0.65) was obtained. The classification was based on the reaction time for missing pulses of 0 ms (corresponding to the time onset of missing pulses) in five S-musicians and eight B-musicians. (b) Scattered plot of error rates versus mean reaction times revealing a linear negative correlation (F(1,11) = 6.9, p = 0.027, r = −0.62). (c) Kernel density estimation (KDE) curves accompanied with histograms for the reaction times of all taps for real pulses separately depicted for S-musicians (curiosity type) and B-musicians (risk-aversion type). The curves indicate dual (faster and slower) populations marked by triangles. Notably, the peak time of approximately 150 ms for the faster populations was common for both S- and B-musicians, whereas that for the slower populations differed. (d) Similar KDE curves as in C for taps for missing pulses. The curves depicted a single-lobe population for both S- and B-musicians. r: Pearson correlation coefficient.

Figure 3.

Group differences in grand-averaged ERP waveforms time-locked to real/missing-pulse onset measured under task and performance conditions for the control (Task 1) and missing-pulse oddball tasks (Task 2). (a) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for the regular sequence (Task 1) providing typical LAEPs including P50, N100, P200, and LPC displaying no significant differences between P- and N-musicians. (b) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for the regular parts of the missing-pulse sequence (Task 2) depicting significant group differences. P-musicians produced the same set of ERPs as observed for the regular sequence (Task 1). By contrast, N-musicians closed N400 while maintaining other ERP components, including P50, N100, and P200. (c)Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for missing pulses under tapping. Significant group differences were observed. P-musicians had a clear P150 and attenuated N200, whereas N-musicians had a clear N200 but no P150. Other ERP components, namely P300 and LPC, were produced by both P and N-musicians. (d) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for missing pulses under tapping avoidance. Group differences were observed. P-musicians produced clear P300 and LPC, whereas N-musicians produced only vague P300.

Figure 3.

Group differences in grand-averaged ERP waveforms time-locked to real/missing-pulse onset measured under task and performance conditions for the control (Task 1) and missing-pulse oddball tasks (Task 2). (a) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for the regular sequence (Task 1) providing typical LAEPs including P50, N100, P200, and LPC displaying no significant differences between P- and N-musicians. (b) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for the regular parts of the missing-pulse sequence (Task 2) depicting significant group differences. P-musicians produced the same set of ERPs as observed for the regular sequence (Task 1). By contrast, N-musicians closed N400 while maintaining other ERP components, including P50, N100, and P200. (c)Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for missing pulses under tapping. Significant group differences were observed. P-musicians had a clear P150 and attenuated N200, whereas N-musicians had a clear N200 but no P150. Other ERP components, namely P300 and LPC, were produced by both P and N-musicians. (d) Grand-averaged ERP waveforms for missing pulses under tapping avoidance. Group differences were observed. P-musicians produced clear P300 and LPC, whereas N-musicians produced only vague P300.

Figure 4.

Characterization of brain responses during the missing-pulse oddball task (Task 2) based on the ER-DBA method. (a): Grand-averaged ER-DBA waveforms time-locked to the real/missing-pulse presentation onset. Taps for real pulses in regular portions of the missing-pulse sequence and for missing pulses are depicted by blue and red lines, respectively. Upper and lower panels present the waveforms for P- and N-musicians, respectively. Gray masks represent prepresentation epochs of interest from −500 to 0 ms. (b) Box charts presenting the average DBA power of ER-DBA waveforms in the pre-presentation epochs of interest. Left and right panels represent P- and N-musicians, respectively. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the Holm–Šídák test as part of one-way ANOVA. All combinations reached the significance level of p = 0.05. (c) Scattered plots of amplitudes and medians elicited from ER-DBA waveforms versus reaction times of taps for missing pulses. The parabolic fitting curve was significant as confirmed by the f-test (F(2,23) = 5.4, p = 0.011).

Figure 4.

Characterization of brain responses during the missing-pulse oddball task (Task 2) based on the ER-DBA method. (a): Grand-averaged ER-DBA waveforms time-locked to the real/missing-pulse presentation onset. Taps for real pulses in regular portions of the missing-pulse sequence and for missing pulses are depicted by blue and red lines, respectively. Upper and lower panels present the waveforms for P- and N-musicians, respectively. Gray masks represent prepresentation epochs of interest from −500 to 0 ms. (b) Box charts presenting the average DBA power of ER-DBA waveforms in the pre-presentation epochs of interest. Left and right panels represent P- and N-musicians, respectively. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the Holm–Šídák test as part of one-way ANOVA. All combinations reached the significance level of p = 0.05. (c) Scattered plots of amplitudes and medians elicited from ER-DBA waveforms versus reaction times of taps for missing pulses. The parabolic fitting curve was significant as confirmed by the f-test (F(2,23) = 5.4, p = 0.011).

Table 1.

Classification of music students into positive-imagery type (P-musicians) and negative-imagery type musicians (N-musicians).

Table 1.

Classification of music students into positive-imagery type (P-musicians) and negative-imagery type musicians (N-musicians).

| Items |

Total |

Subgroups |

| P-musician (positive imagery) |

N-musician (negative imagery) |

| Number (gender) |

14 (female) |

5 (female) |

9 (female) |

| Age: Year: mean (range) |

20.6 (18–22) |

21.4 (19–22) |

20.2 (18–22) |

| Major in academy (N) |

Pianist (11)

Vocalist (2) |

Pianist (5) |

Pianist (6) Vocalist (2) |

Average practice period/ day in academy

Hr: mean (SD) |

1.75 (0.1) |

1.86 (0.12) |

1.65 (0.33) |

| Secondary instrument (family (N)) |

Saxophone (Woodwind) (1)

Flute (Woodwind) (2)

Trumpet (Brass) (2)

Percussion (1) |

Saxophone (Woodwind) (1)

Flute (Woodwind) (1)

Trumpet (Brass) (1)

Percussion (1) |

Trumpet (Brass) (1)

Flute (Woodwind) (1)

|

Period of practice before academy

Years: mean (SD) |

17.4 (5.51) |

18.3 (0.47) |

14.8 (2.47) |

Onset age of music practice

Years: mean (SD) |

4.5 (1.3) |

3.7 (0.47) |

5 (0.47) |

| Piano (13) |

U = 4.5, Z = −1.3, P = 0.17

Value cohen’s d = 1.12

*Mann–Whitney U Test |

| Primary instrument for musical practice (N) |

2 |

Piano (5) |

Piano (8) |

| Number of Students of honor (N) |

2 |

2 |

0 |

| STAI |

State anxiety scores (SD) |

41.09 (6.5) |

40.8 (4.25) |

41.8 (8.1) |

| Trait anxiety scores (SD) |

50.09 (6.4) |

51 (3.78) |

50 (8.87) |

Table 2.

Group differences in amplitudes (μV) (latencies (ms)) of grand-averaged ERP components for regular and missing-pulse sequences.

Table 2.

Group differences in amplitudes (μV) (latencies (ms)) of grand-averaged ERP components for regular and missing-pulse sequences.

| ERP |

Regular (Task 1) |

Real (Task 2) |

Missing (Task 2) |

|

P-musician |

N-musician |

P-musician |

N-musician |

Tap |

Avoid |

| P-musician |

N-musician |

P-musician |

N-musician |

| P50 |

1.83 ***

(50.7) |

0.63 *

(50.7) |

2.27 **

(62.5) |

−0.48

(62.5) |

np |

np |

np |

np |

| N100 |

−1.72 **

(105.4) |

−1.006 ***

(97.6) |

−2.47 ***

(105.4) |

−2.24 ***

(105.4) |

np |

np |

np |

np |

| P200 |

3.99 ***

(183.5) |

4.82 ***

(171.8) |

7.11 ***

(207) |

6.10 ***

(191.4) |

np |

np |

np |

np |

P300

|

np |

np |

np |

np |

11.5

(363.2) |

9.03

(359.3) |

14.7

(328.1) |

9.08

(343.7) |

| N400 |

−0.95

(328.1) |

−0.79

(335.9) |

−1.23

(406.2) |

3.71

(406.2) |

np |

np |

np |

np |

| LPC |

1.86

(500–800) |

1.34

(500–800) |

1.4

(500–800) |

2.23

(500–800) |

5.05

(500–800) |

5.1

(500–800) |

4.73

(500–800) |

1.58

(500–800) |

| P150 |

|

|

|

|

4.33 ***

(125) |

np |

np |

np |

| N200 |

|

|

|

|

0.508

(199.2) |

−4.15 ***

(195.3) |

np |

np |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).