Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

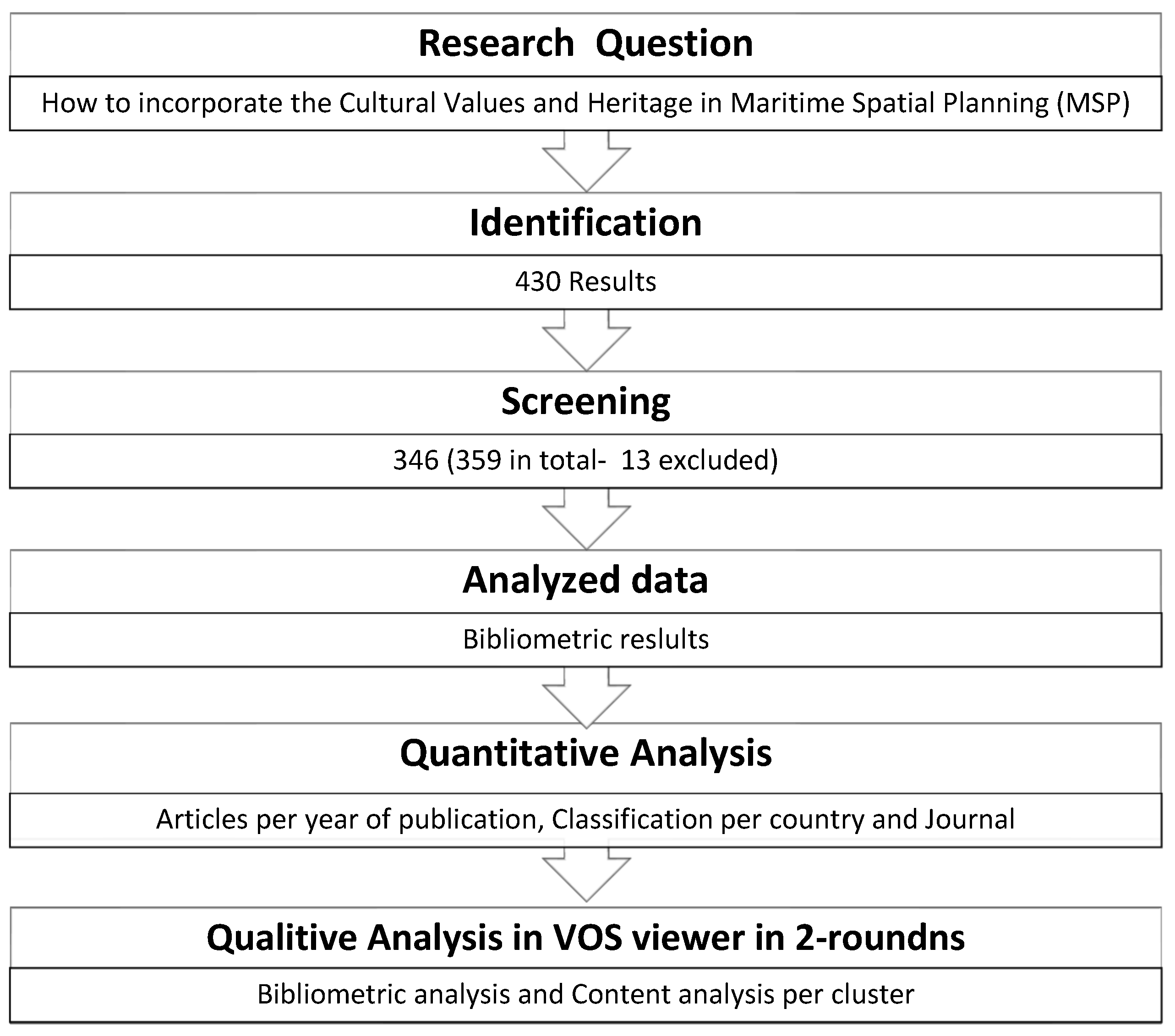

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Systematic Literature Review linking MUCH and MSP

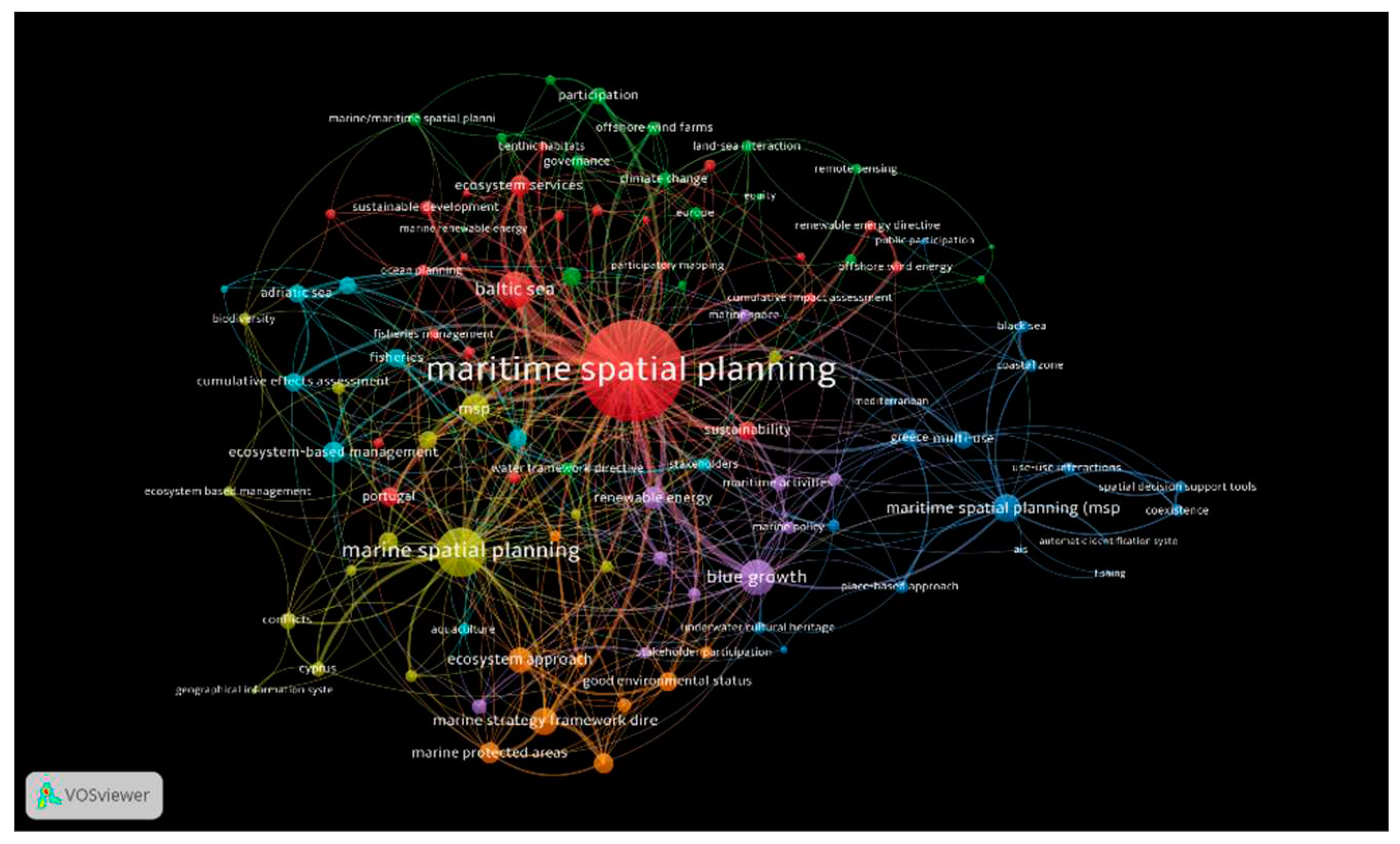

2.2. Science mapping and visualization analysis- Bibliometric VOSviewer Analysis

- Search on Scopus, within the Article, Title, and Keywords, the term "maritime spatial planning".

- The resulting articles from the search were collected.

- Running the VOS viewer software, by inserting the previous articles (Figure 5).

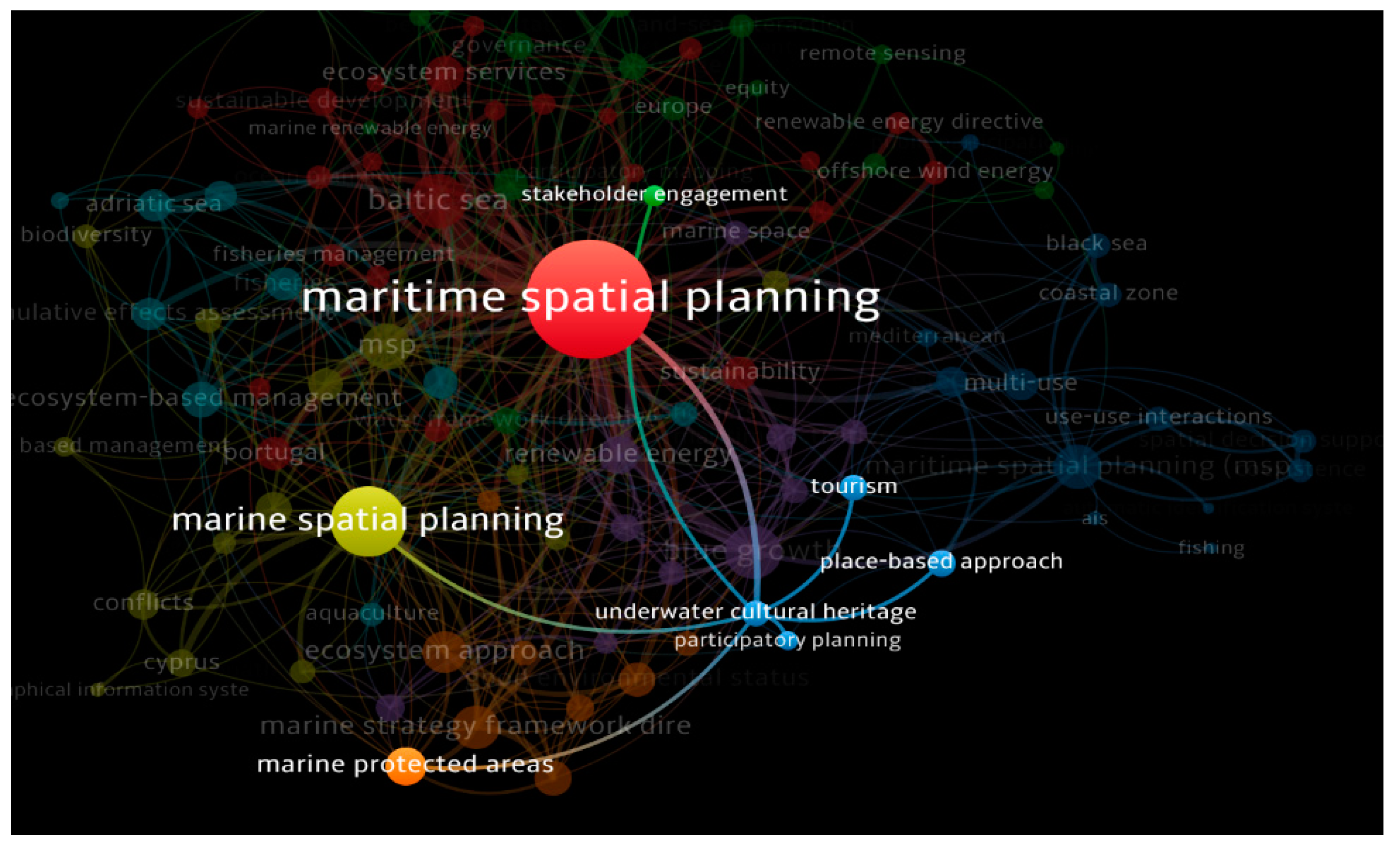

- Zoom in the Underwater Cultural Heritage connections (Figure 6).

- Search on Scopus, "Maritime spatial planning" OR "coastal planning" OR "marine planning" OR "marine policy" OR "coastal policy" and Search in Title, Abstract, and Keywords for “Underwater cultural heritage," OR "maritime cultural heritage," OR "cultural ecosystem services," OR "intangible heritage," OR "marine cultural heritage," OR "cultural values" OR "socio-cultural values" OR "tangible heritage"( see also Table 1 above )

- The resulting articles from the search were collected.

- Excluding some of the identified articles according to several criteria ( see section 2)

- Running the VOS viewer software, by inserting the previous articles.

- Analysis of the VOS Viewer science map, per created cluster.

3. Results

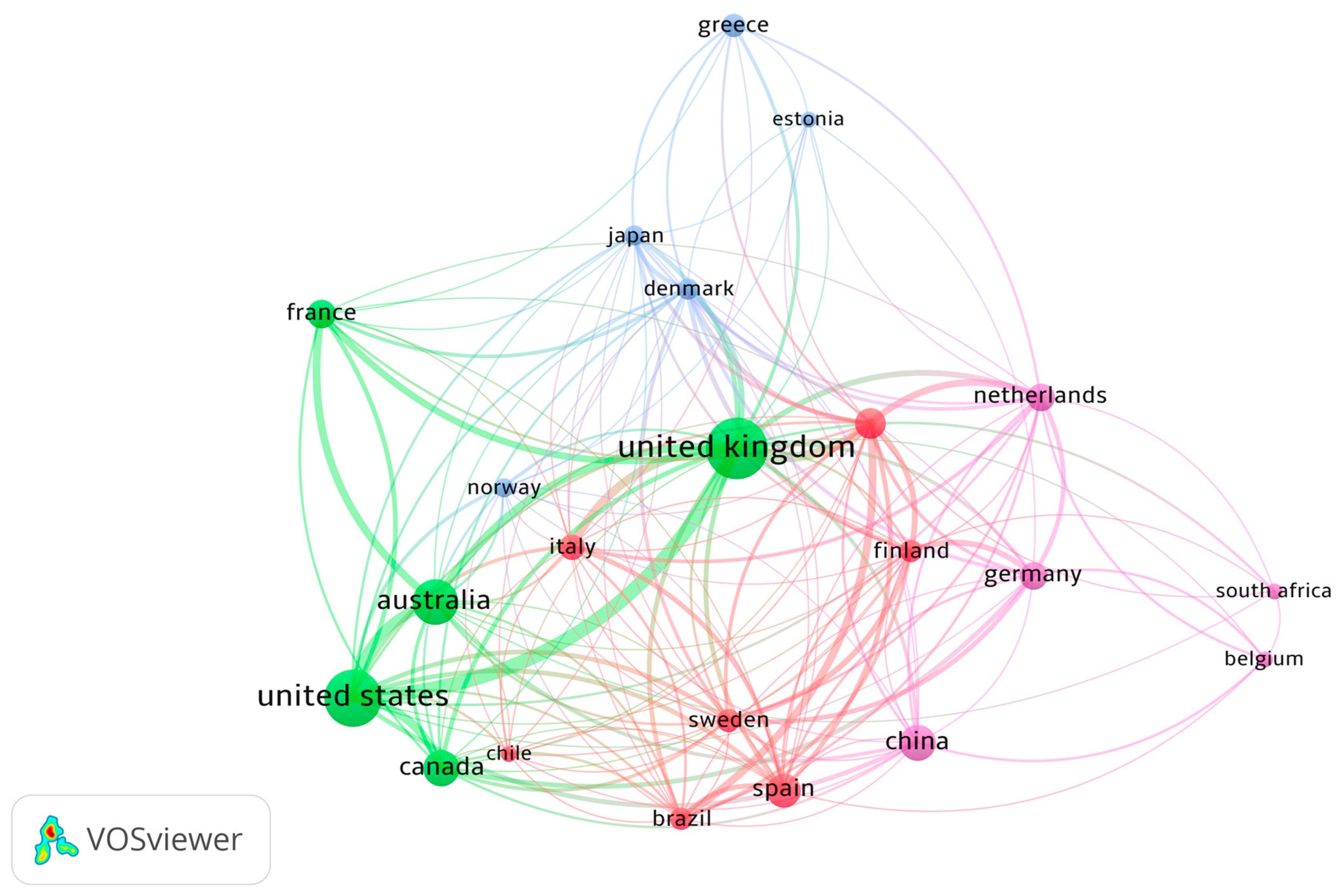

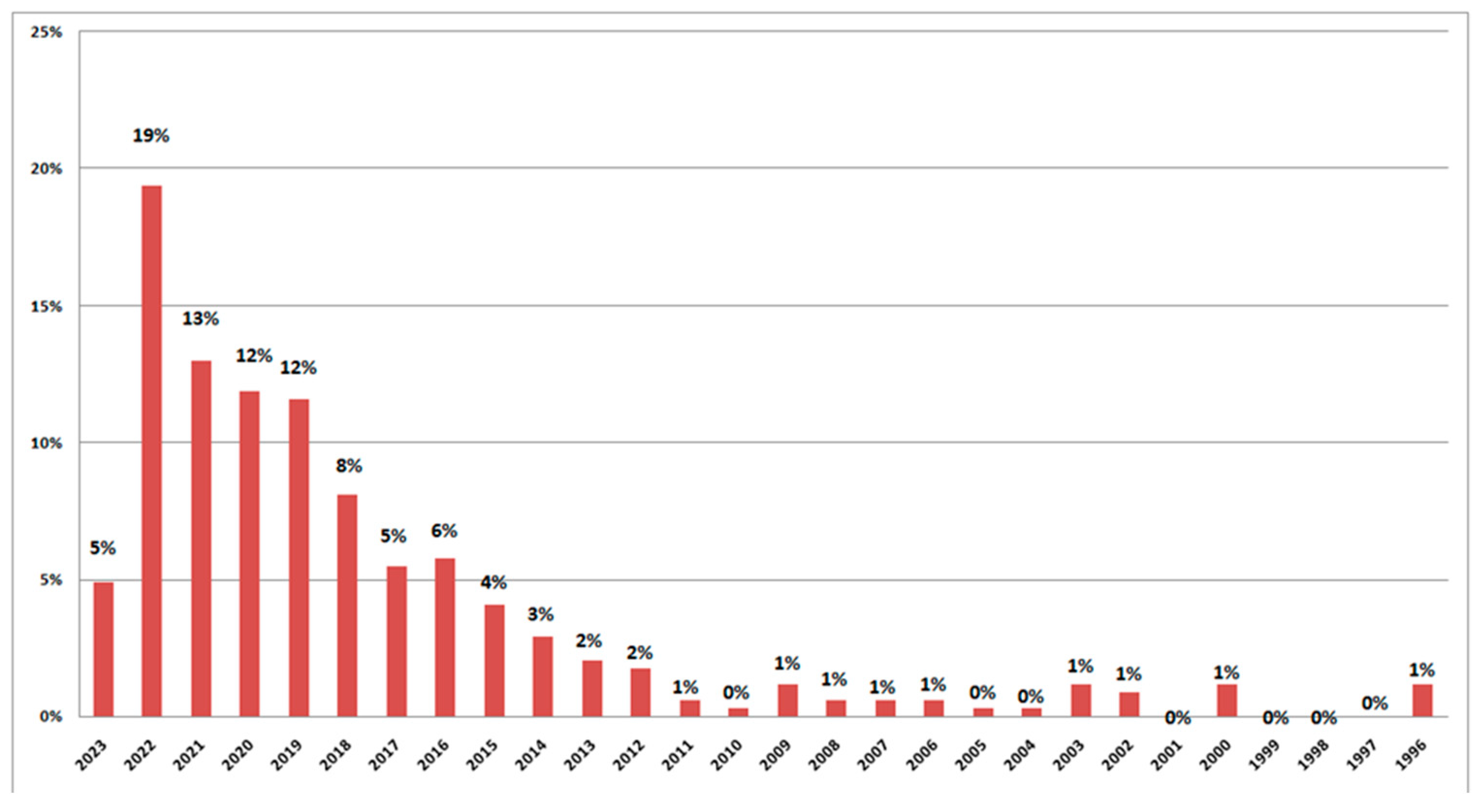

3.1. Quantitative analysis through VOSviewer

3.2. Qualitative analysis

- The place-based approach is a key principle in MSP [18]. It means that MSPplans are tailored to each marine area's particular characteristics. This is mostly important for UCH because it allows for developing tailor-made management measures that protect UCH sites and objects while supporting sustainable economic and social development. For example, a MSPlan in a marine area with high concentration of historical shipwrecks might incorporate measures (spatial and non-spatial) to restrict fishing activities or regulate diving tourism in these areas.

- Protected areas are another vital aspect in UCH management. Protected areas can contribute to both protection and conservation of both natural and cultural heritage [19] (UCH sites and objects) against damage and disturbance from other activities. MSP is decisive in identifying and designating appropriate marine protected areas (MPAs) and zones for UCH and in developing management measures for those areas. For example, a MSPplan might define a marine area with historic shipwrecks as a protected area, with restrictive measures concerning fishing, anchoring or diving tourism.

- Stakeholder engagement is essential for the accomplishment of MSP. Stakeholders are individuals or groups interested in or affected by UCH or MSP. MSP should engage stakeholders at an early stage and during the planning itself to warrant that their specific interests and values are fully respected. During the MSP process, stakeholders can be engaged for UCH conservation in several ways, including communities of practice [20], representative stakeholders’ forums, advisory groups, public hearings, or interviews. A successful engagement of stakeholders is a critical factor that shows that values and interests of all interested parties are considered in the development of MSplans for UCH.

- Participatory mapping is a process in which community members provide their own knowledge and experience about a place, to building a map [10]. It is a tool used to engage stakeholders in the MSP process. Participatory mapping can identify and map UCH sites and objects but also collect information about beliefs, interests and values of the different stakeholders. MSplans may use this input to develop protection measures for UCH while supporting stakeholders' desires and visions.

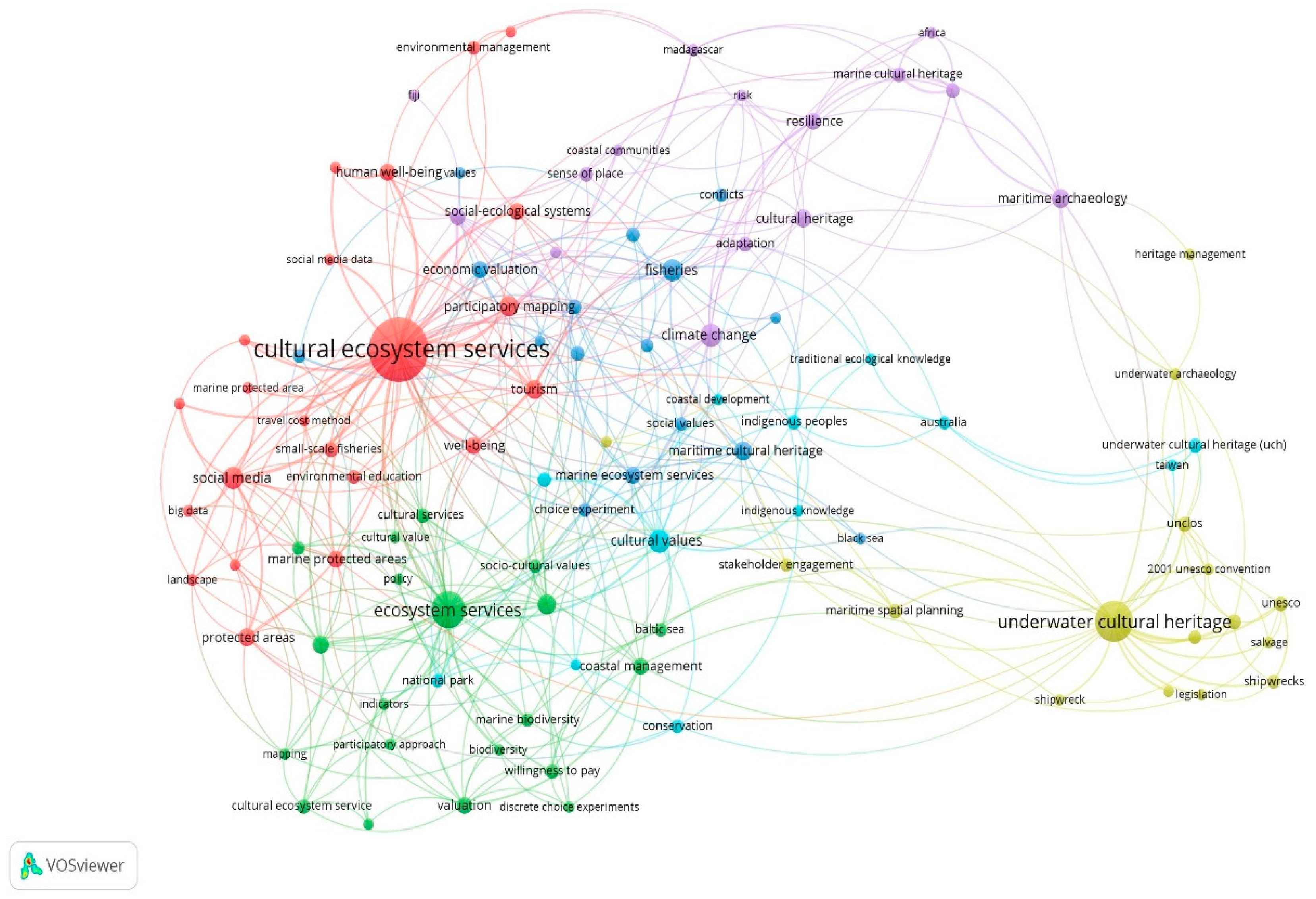

3.2.2. Cluster analysis

- Red Cluster - "Cultural Ecosystem Services, Participatory Mapping and Recreation” being a group of 87 articles

- Green Cluster - “Ecosystem services, marine biodiversity and MUCH“as a group of 49 articles.

- Blue cluster - “Fisheries, food security, conflicts over fisheries and MUCH” thematic cluster created by 61 articles.

- Yellow Cluster - "MUCH legislative and institutional framework and sustainable development “as a group of 55 articles.

- Purple Cluster - "Coastal Communities, climate change and sustainable development“, thematic cluster created by 53 articles.

- Light Blue Cluster - “Cultural values, indigenous traditional knowledge, PPGIS”, thematic cluster created by 35 articles.

- 1.

- Red Cluster - "Cultural Ecosystem Services, Participatory Mapping and Recreation”

- 2.

- Green Cluster – “Ecosystem services, marine biodiversity and MUCH”

- 3.

- Blue cluster – “Fisheries, food security, conflicts over fisheries and MUCH”

- 4.

- Yellow Cluster - "MUCH legislative and institutional framework and sustainable development"

- 5.

- Purple Cluster - "Coastal Communities, climate change, sustainable development and cultural values"

- 6.

- Light Blue – “Cultural values, indigenous traditional knowledge, PPGIS”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and further research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Articles | citations | linkages |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 85 | 2532 | 76 |

| United States | 75 | 1673 | 54 |

| Australia | 48 | 1194 | 31 |

| China | 30 | 102 | 14 |

| Canada | 29 | 1049 | 24 |

| Spain | 25 | 354 | 20 |

| Portugal | 20 | 168 | 45 |

| France | 19 | 410 | 30 |

| Netherlands | 17 | 828 | 40 |

| Germany | 16 | 388 | 32 |

| Italy | 15 | 827 | 19 |

| Greece | 13 | 130 | 14 |

| Brazil | 11 | 201 | 21 |

| Sweden | 11 | 411 | 20 |

| Finland | 10 | 142 | 21 |

| Denmark | 9 | 99 | 29 |

| Japan | 9 | 96 | 16 |

| Norway | 8 | 278 | 6 |

| Belgium | 6 | 75 | 9 |

| Estonia | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| South Africa | 6 | 81 | 7 |

| Chile | 5 | 144 | 1 |

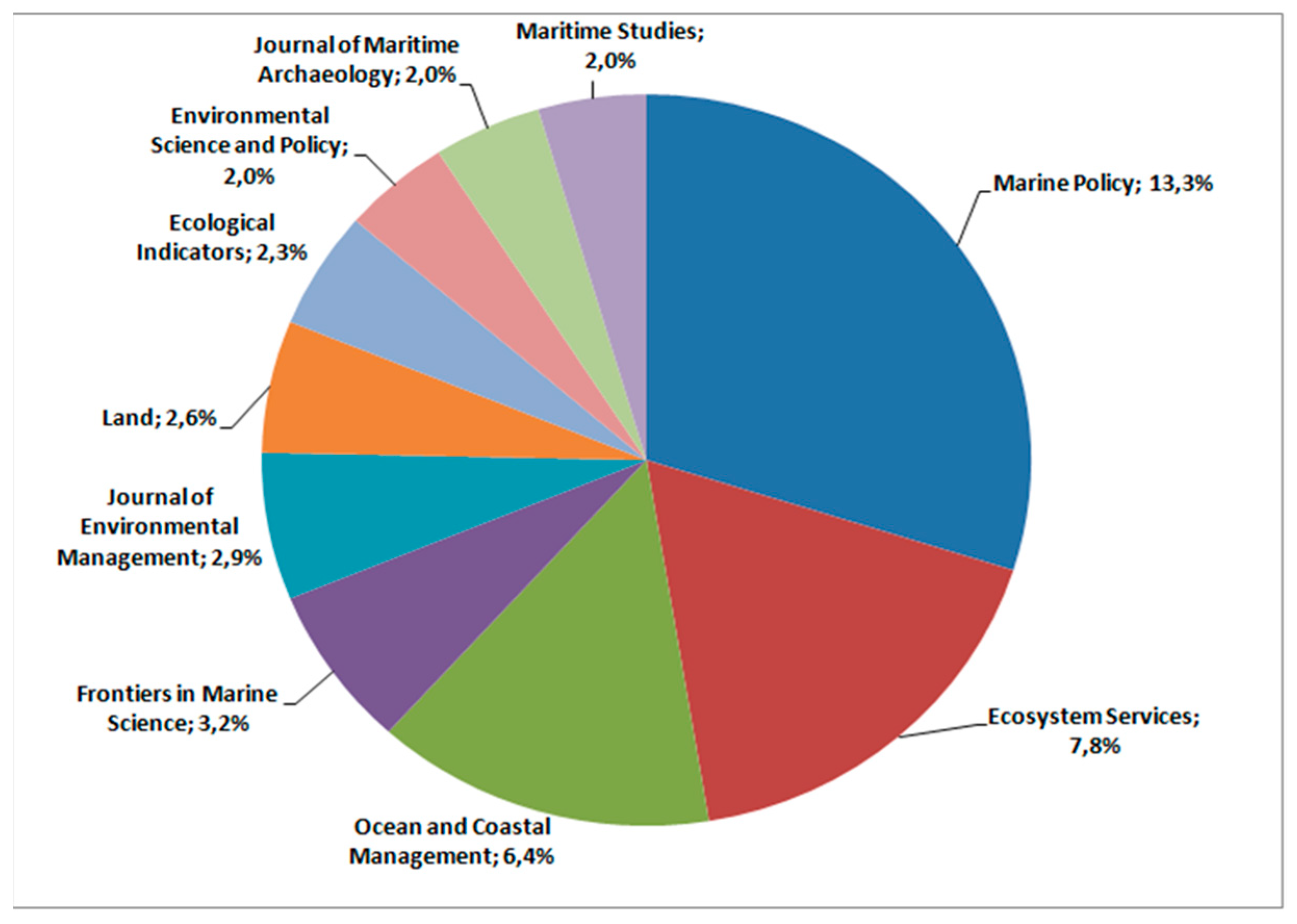

| Journal | articles |

|---|---|

| “Marine Policy” | 46 |

| “Ecosystem Services” | 27 |

| “Ocean and Coastal Management” | 22 |

| “Frontiers in Marine Science” | 11 |

| “Journal of Environmental Management” | 10 |

| “Land” | 9 |

| “Ecological Indicators” | 8 |

| “Environmental Science and Policy” | 7 |

| “Journal of Maritime Archaeology” | 7 |

| “Maritime Studies” | 7 |

| “Coastal Management” | 6 |

| “Ecological Economics” | 6 |

| “Global Environmental Change” | 6 |

| “Heritage” | 6 |

| “Ocean Development and International Law” | 6 |

| “People and Nature” | 6 |

| “Sustainability (Switzerland)” | 6 |

| “Ambio” | 4 |

| “Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science” | 4 |

| “Landscape Ecology” | 4 |

| “Applied Geography” | 3 |

| “Conservation Biology” | 3 |

| “Ecology and Society” | 3 |

| “International Journal of Cultural Property” | 3 |

| “International Journal of Nautical Archaeology” | 3 |

| “Land Use Policy” | 3 |

| “Science of the Total Environment” | 3 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Cluster | Green Cluster | Blue Cluster | Yellow Cluster | Purple Cluster | Light Blue Cluster |

| Cultural ecosystem services, Participatory Mapping & Recreation | Ecosystem services & Marine biodiversity | Fisheries, food security & conflicts | MUCH legislation & Institutional framework | Coastal communities, climate change & Sustainable development | Cultural values, indigenous, traditional knowledge |

| big data | Baltic sea | aquaculture | 2001 Unesco Covention |

adaptation | Australia |

| cultural ecosystem | biodiversity | Black sea | cultural ecosystem services | Africa | coastal development |

| cultural ecosystem services | coastal management | choice experiment | heritage management | climate change | conservation |

| ecosystem service value | cultural ecosystem service | conflicts | law of the sea | coastal communities | cultural values |

| environmental education | cultural services | economic valuation |

legislation | coral reefs | development |

| environmental management | cultural value | ecosystem based management | maritime spatial planning | cultural heritage | Indigenous knowledge |

| human well being | discrete choice experiment | fisheries | salvage | Fiji | indigenous people |

| landscape | ecosystem services | food security | shipwreck | Madagascar | national park |

| mangrove | indicators | local knowledge | shipwrecks | marine cultural heritage | PPGIS |

| marine protected areas | mapping | marine ecosystem services | South China sea | maritime archaeology | Taiwan |

| marine protected area | marine biodiversity | marine cultural heritage | stakeholder engagement | resilience | Traditional Ecological Knowledge |

| nature based recreation | marine spatial planning | non-monetary valuation | treasure salvage | risk | Underwater cultural heritage |

| participatory mapping | natural resources | relational values | Unclos | sense of place | |

| protected areas | participatory approach |

science policy interface | underwater archaeology | sustainability | |

| small scale fisheries |

policy | social values | underwater cultural heritage | sustainable development | |

| social media | recreation | values | Unesco | ||

| social media data | sociocultural values |

||||

| social ecological system | spatial analysis | ||||

| supply and demand | valuation | ||||

| tourism | willingness to pay | ||||

| travel cost method | |||||

| user generated content | |||||

| well-being |

References

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Social and Economic Committee and the Committee of the Regions, The European Green Deal, COM/2019/640 final, (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Social and Economic Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU Transforming the EU's Blue Economy for a Sustainable Future, COM/2021/240 final (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Pennino Maria Grazia, Brodie Stephanie, Frainer André, Lopes Priscila F. M., Lopez Jon, Ortega-Cisneros Kelly, Selim Samiya, Vaidianu Natasa, The Missing Layers: Integrating Sociocultural Values Into Marine Spatial Planning, Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, Volume 8. [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Acott, T., Stojanovic, T. Socio-cultural dimensions of marine spatial planning. In Book Maritime Spatial Planning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019, pp. 151-174.

- M.E.A. (2005) A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. Island Press, Washington DC.

- Kobryn, H.T., Brown, G., Munro, J., Moore, S.A., 2018. Cultural ecosystem values of the Kimberley coastline: An empirical analysis with implications for coastal and marine policy. Ocean & Coastal Management 162, 71–84. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A., Guerry, A.D., Balvanera, P., Klain, S., Satterfield, T., Basurto, X., ..., Woodside, U., 2012b. Where are cultural and social in ecosystem services? A framework for constructive engagement. BioScience 62 (8), 744e756. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Directorate General for Fisheries and Maritime Affairs, MSPglobal: international guide on marine/maritime spatial planning, IOC/2021/MG/89, ISBN :148 pages, 2021.

- Stella Sofia Kyvelou, Yves Henocque, How to incorporate underwater cultural heritage into maritime spatial planning: guidelines and good practices, EUROPEAN COMMISSION, European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency Unit D.3 – Sustainable Blue Economy, April 2022, ISBN 978-92-95225-51-0. [CrossRef]

- Denise Blake; Amélie A.; Augé, Kate Sherren, Participatory mapping to elicit cultural coastal values for Marine Spatial Planning in a remote archipelago, Ocean & Coastal Management, 2017, Volume 148, Pages 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Anna Tengberg; Susanne Fredholm; Ingegard Eliasson; Igor Knez; Katarina Saltzman; Ola Wetterberg. Cultural ecosystem services provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity, Ecosystem Services, 2012, Volume 2, pp. 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frau; H. Hinz; G. Edwards-Jones; M.J. Kaiser, Spatially explicit economic assessment of cultural ecosystem services: Non-extractive recreational uses of the coastal environment related to marine biodiversity, Marine Policy, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Christina Kelly; Lorraine Gray; Rachel Shucksmith; Jacqueline F. Tweddle, Review and evaluation of marine spatial planning in the Shetland Islands, Marine Policy, 2014, Volume 46, Pages 152-160. [CrossRef]

- S. Khakzad and D. Griffith, ‘The Role of Fishing Material Culture in Communities’ Sense of Place as an Added-Value in Management of Coastal Areas’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, 2016, Vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 95–117. [CrossRef]

- Kira Gee, Andreas Kannen, Robert Adlam, Cecilia Brooks, Mollie Chapman, Roland Cormier, Christian Fischer, Steve Fletcher, Matt Gubbins, Rachel Shucksmith, Rebecca Shellock, Identifying culturally significant areas for marine spatial planning, Ocean & Coastal Management, 2017, Volume 136, Pages 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Liisi Lees, Krista Karro, Francisco R. Barboza, Ann Ideon, Jonne Kotta, Triin Lepland, Maili Roio, Robert Aps, Integrating maritime cultural heritage into maritime spatial planning in Estonia, Marine Policy, 2023,Volume 147,105337. [CrossRef]

- Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning OJ L 257, 28.8.2014. accessible at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014L0089.

- Kyvelou, S. (2017). Maritime Spatial Planning as Evolving Policy in Europe: Attitudes, Challenges and Trends. European Quarterly of Political Attitudes and Mentalities, 6(3), 1-14. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-54497-5.

- Kyvelou S-S.; Chiotinis M.; Reconnecting Natural and Cultural Capital: Historical Viewpoints and Emerging Planning Strategies in the Marine Space, In Proceedings of Mo.Na: Monuments in Nature: A Creative co-existence, International Conference Athens, 7-9 July, 2021.

- Kyvelou S. “What is a Community of Practice?”, Presentation during the REGINA-MSP ( Regions to boost national Maritime Spatial Planning) Workshop, Thessaloniki 18-20 October, 2023.

- Sarah C. Klain; M.A. Chan, Navigating coastal values: Participatory mapping of ecosystem services for spatial planning, Ecological Economics, 2012, Volume 82, Pages 104-113. [CrossRef]

- Ruth Fletcher et al., “Revealing Marine Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Black Sea,” Marine Policy, 2014, Vol. 50 pp. 151–61. [CrossRef]

- Daniel A. Friess et al., Indicators of Scientific Value: An under-Recognised Ecosystem Service of Coastal and Marine Habitats, Ecological Indicators, 2020, Vol. 113 : 3. [CrossRef]

- C. Román et al., “Surfing the Waves: Environmental and Socio-Economic Aspects of Surf Tourism and Recreation,” Science of the Total Environment 826 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C.L. Martin et al., “Mapping the Intangibles: Cultural Ecosystem Services Derived from Lake Macquarie Estuary, New South Wales, Australia,” Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2020, Vol.243. [CrossRef]

- Margarida Ferreira Da Silva et al., “Tourism and Coastal & Maritime Cultural Heritage: A Dual Relation,” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2022, Vol.20, no. 6 : pp. 806–26. [CrossRef]

- Banarsyadhimi, U.R.A.M.F., P. Dargusch, and F. Kurniawan. “Assessing the Impact of Marine Tourism and Protection on Cultural Ecosystem Services Using Integrated Approach: A Case Study of Gili Matra Islands.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19, no. 19. [CrossRef]

- Marina Banela, Dimitra Kitsiou, Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A case study in Lesvos Island, Greece, Ocean & Coastal Management, 2023, Volume 246, 106883. [CrossRef]

- Miguel Inácio et al., “Mapping and Assessing Coastal Recreation Cultural Ecosystem Services Supply, Flow, and Demand in Lithuania, Journal of Environmental Management 2022, vol.323 : 116175. [CrossRef]

- Anda Ruskule, Andris Klepers, and Kristina Veidemane, “Mapping and Assessment of Cultural Ecosystem Services of Latvian Coastal Areas,” One Ecosystem 2018, 3 : e25499. [CrossRef]

- R. Fish, A. Church, and M. Winter, Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement, Ecosystem Services, 2016, Vol.21 208–17. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths V. F. et al., ‘Incorporating Local Nature-Based Cultural Values into Biodiversity No Net Loss Strategies’, World Development, 2020, 128. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Iqbal Mohd Noor et al., ‘Perspectives of Youths on Cultural Ecosystem Services Provided by Tun Mustapha Park, Malaysia through a Participatory Approach’, Environmental Education Research, 2023, Vol.29, no. 1 : pp. 63–80. [CrossRef]

- Moseley Rachel D., Hampel Justyna J., Mugge Rachel L., Hamdan Leila J. Historic Wooden Shipwrecks Influence Dispersal of Deep-Sea Biofilms, Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022, Vol.9.

- C. Hofmeester et al., “Social Cultural Influences on Current and Future Coastal Governance,” Futures, 2012, Vol.44, no. 8 : pp. 719–29. [CrossRef]

- H. Calado et al., “Multi-Uses in the Eastern Atlantic: Building Bridges in Maritime Space,” Ocean and Coastal Management, 2019, Vol. 174 : pp. 131–43. [CrossRef]

- Taryn Laubenstein et al., ‘Threats to Australia’s Oceans and Coasts: A Systematic Review’, Ocean & Coastal Management, 2023 Vol.31 : 106331. [CrossRef]

- A. Azevedo, “Using Social Media Photos as a Proxy to Estimate the Recreational Value of (Im)Movable Heritage: The Rubjerg Knude (Denmark) Lighthouse,” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33, no. 6 (2020): 2283–2303. [CrossRef]

- Q. Schuyler et al., “Environmental Context and Socio-Economic Status Drive Plastic Pollution in Australian Cities,” Environmental Research Letters 17, no. 4 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Suvi Ignatius and Päivi Haapasaari, “Justification Theory for the Analysis of the Socio-Cultural Value of Fish and Fisheries: The Case of Baltic Salmon,” Marine Policy 88 (February 2018): 167–73. [CrossRef]

- Charlie Short et al., “Marine Zoning for the Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP) in British Columbia, Canada,” Marine Policy, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Stithou, M. Kourantidou, and V. Vassilopoulou, ‘Sociocultural Ecosystem Services of Small-Scale Fisheries: Challenges, Insights and Perspectives for Marine Resource Management and Planning’, Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management 25, no. 3 (1 July 2022): 22–33. [CrossRef]

- Madu Galappaththi et al., ‘Linking Social Wellbeing and Intersectionality to Understand Gender Relations in Dried Fish Value Chains’, Maritime Studies 20, no. 4 (December 2021): 355–70. [CrossRef]

- E. Spanou, J. O. Kenter, and M. Graziano, ‘The Effects of Aquaculture and Marine Conservation on Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Integrated Hedonic – Eudaemonic Approach’, Ecological Economics 176 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Gómez, A. Carreño, and J. Lloret, ‘Cultural Heritage and Environmental Ethical Values in Governance Models: Conflicts between Recreational Fisheries and Other Maritime Activities in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas’, Marine Policy 129 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Stratigea, A. Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean. Heritage 2019, 2, 1588-1613. [CrossRef]

- Maragno, Denis and dall'Omo, Francesco and Pozzer, Gianfranco, Coastal Areas in Transition. Assessment Integration Techniques to Support Local Adaptation Strategies to Climate Impacts (July 16, 2020). FEEM Policy Brief No. 14-2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3711345.

- J.R.A. Butler et al., ‘Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Fisheries Management in the Torres Strait, Australia:The Catalytic Role of Turtles and Dugong as Cultural Keystone Species’, Ecology and Society 17, no. 4 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D.G.; Chiotinis, M. The Future of Fisheries Co-Management in the Context of the Sustainable Blue Economy and the Green Deal: There Is No Green without Blue. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7784. [CrossRef]

- Alicia Said, Brice Trouillet. Bringing ‘Deep Knowledge’ of Fisheries into Marine Spatial Planning. Maritime Studies, 2020, 19, pp.347-357. [CrossRef]

- S. Chakraborty and A. Gasparatos, ‘Community Values and Traditional Knowledge for Coastal Ecosystem Services Management in the “Satoumi” Seascape of Himeshima Island, Japan’, Ecosystem Services 37 (2019). [CrossRef]

- H. Conejo-Watt et al., ‘Fishers Perspectives on the Barriers for the English Inshore Fleet to Diversify into Aquaculture’, Marine Policy 131 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Conejo-Watt et al.; J. Cumberbatch and C. Hinds, ‘Barbadian Bio-Cultural Heritage: An Analysis of the Flyinq Fish’, International Journal of Intangible Heritage 8 (2013): 117–34.

- Janice Cumberbatch, Crystal Drakes , Tara Mackey , Mohammad Nagdee , Jehroum Wood , Anna Karima Degia & Catrina Hinds : Social Vulnerability Index: Barbados – A Case Study, Coastal Management, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Depellegrin et al., ‘Assessing Marine Ecosystem Services Richness and Exposure to Anthropogenic Threats in Small Sea Areas: A Case Study for the Lithuanian Sea Space’, Ecological Indicators 108 (2020). [CrossRef]

- R. Durán, B.A. Farizo, and M.X. Rodríguez, ‘Conservation of Maritime Cultural Heritage: A Discrete Choice Experiment in a European Atlantic Region’, Marine Policy 51 (2015): 356–65. [CrossRef]

- L.E. Eckert et al., ‘Diving Back in Time: Extending Historical Baselines for Yelloweye Rockfish with Indigenous Knowledge’, Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 28, no. 1 (2018): 158–66. [CrossRef]

- L. Ernoul et al., ‘Context in Landscape Planning: Improving Conservation Outcomes by Identifying Social Values for a Flagship Species’, Sustainability (Switzerland) 13, no. 12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Galappaththi et al., ‘Linking Social Wellbeing and Intersectionality to Understand Gender Relations in Dried Fish Value Chains’, Maritime Studies 20, no. 4 (2021): 355–70. [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou, S.S.I.; Ierapetritis, D.G. Fisheries Sustainability through Soft Multi-Use Maritime Spatial Planning and Local Development Co-Management: Potentials and Challenges in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2026. [CrossRef]

- Kyvelou, S.S.I.; Ierapetritis, D.G. Fostering spatial efficiency in the marine space, in a socially sustainable way: lessons learnt from a soft multi-use (MU) assessment in the Mediterranean, Frontiers in Marine Science, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Stancheva et al., ‘Supporting Multi-Use of the Sea with Maritime Spatial Planning. The Case of a Multi-Use Opportunity Development - Bulgaria, Black Sea’, Marine Policy 136 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M., Kyvelou, S.: Aspects of marine spatial planning and governance: adapting to the transboundary nature and the special conditions of the sea European Journal of Environmental Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 31–37. [CrossRef]

- P.A. Loring and S.C. Gerlach, ‘Food, Culture, and Human Health in Alaska: An Integrative Health Approach to Food Security’, Environmental Science and Policy 12, no. 4 (2009): 466–78. [CrossRef]

- G.M. Andreou et al., ‘Exploring the Impact of Tropical Cyclones on Oman’s Maritime Cultural Heritage Through the Lens of Al-Baleed, Salalah (Dhofar Governorate)’, Journal of Maritime Archaeology 17, no. 3 (2022): 465–86. [CrossRef]

- Leyla D Bashirova, ‘On the Legal Status of Maritime Cultural Heritage and Its Management in the Russian Sectors of the Baltic Sea’, Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 2021.

- Sarah Dromgoole, ‘Reflections on the Position of the Major Maritime Powers with Respect to the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001’, Marine Policy, 2013, Vol. 38 : 116–23. [CrossRef]

- Sarah Dromgoole, ‘Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001)’, in Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Xintong Li.; Yen-Chiang Chang; A step closer to the convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage 2001: China’s latest efforts in regulation, Marine Policy, 2023, Volume 147, 105346. [CrossRef]

- B. Lu and S. Zhou, China’s State-Led Working Model on Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage: Practice, Challenges, and Possible Solutions, Marine Policy, 2016, Vol. 65 : 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lin, Chinese Legislation on Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage in Marine Spatial Planning and Its Implementation, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lin, ‘Issues in Underwater Cultural Heritage Impact Assessments in China’, Coastal Management 47, 2019, no. 6 : 548–69. [CrossRef]

- B. Lu and S. Zhou, China’s State-Led Working Model on Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage: Practice, Challenges, and Possible Solutions, Marine Policy, 2016, Vol. 65 : 39–47. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhong, ‘Underwater Cultural Heritage and the Disputed South China Sea’, China Information, 2020, 34, no. 3: 361–82. [CrossRef]

- M. Strand, N. Rivers, and B. Snow, ‘The Complexity of Evaluating, Categorising and Quantifying Marine Cultural Heritage’, Marine Policy 148 (February 2023). [CrossRef]

- J.D. Lau et al., ‘What Matters to Whom and Why? Understanding the Importance of Coastal Ecosystem Services in Developing Coastal Communities’, Ecosystem Services 35 (2019): 219–30. [CrossRef]

- Kristen Ounanian et al., ‘Conceptualizing Coastal and Maritime Cultural Heritage through Communities of Meaning and Participation’, Ocean & Coastal Management 212 (October 2021): 105806. [CrossRef]

- Kristen Ounanian and Matthew Howells, ‘Clinker, Sailor, Fisher, Why? The Necessity of Sustained Demand for Safeguarding Clinker Craft Intangible Cultural Heritage’, Maritime Studies 21, no. 4 (December 2022): 411–23. [CrossRef]

- Beverley Clarke, Selina Tually, and Michael Scott, ‘Social Networks and Decision-Making for Coastal Land-Use Planning, Development and Adaptation Response’, Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 8, no. 2 (2 April 2016): 101–16. [CrossRef]

- B. Clarke et al., ‘Integrating Cultural Ecosystem Services Valuation into Coastal Wetlands Restoration: A Case Study from South Australia’, Environmental Science and Policy 116 (2021): 220–29. [CrossRef]

- G. Holly et al., ‘Utilizing Marine Cultural Heritage for the Preservation of Coastal Systems in East Africa’, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 5 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Malinauskaite et al., ‘Socio-Cultural Valuation of Whale Ecosystem Services in Skjálfandi Bay, Iceland’, Ecological Economics 180 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B.E. Escamilla-Pérez et al., ‘Cultural Importance of Marine Resources Subject to Fishing Exploitation in Coastal Communities of Southwest Gulf of Mexico’, Ocean and Coastal Management 208 (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Brown and V.H. Hausner, An Empirical Analysis of Cultural Ecosystem Values in Coastal Landscapes, Ocean and Coastal Management, 2017, Vol.142 : 49–60. [CrossRef]

- R.H. Bark et al., “Operationalising the Ecosystem Services Approach in Water Planning: A Case Study of Indigenous Cultural Values from the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia,” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services and Management 11, no. 3 (2015): 239–49. [CrossRef]

- Kamaljit K. Sangha et al., “A State-Wide Economic Assessment of Coastal and Marine Ecosystem Services to Inform Sustainable Development Policies in the Northern Territory, Australia,” Marine Policy 107 (September 2019): 103595. [CrossRef]

- A. Freitag, T. Hartley, and B. Vogt, “Using Business Names as an Indicator of Oysters’ Cultural Value,” Ecological Complexity 31 (2017): 165–69. [CrossRef]

- John McCarthy et al., “Beneath the Top End: A Regional Assessment of Submerged Archaeological Potential in the Northern Territory, Australia,” Australian Archaeology 88, no. 1 (January 2022): 65–83. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Adams et al., “Local Values and Data Empower Culturally Guided Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management of the Wuikinuxv Bear–Salmon–Human System,” Marine and Coastal Fisheries 13, no. 4 (2021): 362–78. [CrossRef]

- S. Leonard et al., The Role of Culture and Traditional Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia, Global Environmental Change 23, no. 3 (2013): 623–32. [CrossRef]

- Carrie Oloriz and Brenda Parlee, Towards Biocultural Conservation: Local and Indigenous Knowledge, Cultural Values and Governance of the White Sturgeon (Canada), Sustainability 12, no. 18 (September 7, 2020): 7320. [CrossRef]

- Pierre-Yves Le Meur and Alexander Mawyer, “France and Oceanian Sovereignties,” Oceania 92, no. 1 (March 2022): 9–30. [CrossRef]

- J. Colding, C. Folke, and T. Elmqvist, “Social Institutions in Ecosystem Management and Biodiversity Conservation,” Tropical Ecology 44, no. 1 (2003): 25–41.

- K. Miyamoto et al., “Traditional Knowledge of Medicinal Plants on Gau Island, Fiji: Differences between Sixteen Villages with Unique Characteristics of Cultural Value,” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 17, no. 1 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Lavoie et al., “Engaging with Women’s Knowledge in Bristol Bay Fisheries through Oral History and Participatory Ethnography,” Fisheries 44, no. 7 (2019): 331–37. [CrossRef]

- T.D. Ramm et al., “Advancing Values-Based Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation: A Case Study from Australia,” Environmental Science and Policy 76 (2017): 113–23. [CrossRef]

- Freitag, Hartley, and Vogt, “Using Business Names as an Indicator of Oysters’ Cultural Value.”.

- O. Saif, A. Keane, and S. Staddon, “Making a Case for the Consideration of Trust, Justice, and Power in Conservation Relationships,” Conservation Biology 36, no. 4 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K.L.L. Oleson et al., “Cultural Bequest Values for Ecosystem Service Flows among Indigenous Fishers: A Discrete Choice Experiment Validated with Mixed Methods,” Ecological Economics 114 (2015): 104–16. [CrossRef]

- B. Bishop et al., “How Icebreaking Governance Interacts with Inuit Rights and Livelihoods in Nunavut: A Policy Review,” Marine Policy 137 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H.O. Braga et al., “Fishers’ Knowledge on Historical Changes and Conservation of Allis Shad -Alosa Alosa (Linnaeus, 1758) in Minho River, Iberian Peninsula,” Regional Studies in Marine Science 49 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Vierros, “Communities and Blue Carbon: The Role of Traditional Management Systems in Providing Benefits for Carbon Storage, Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihoods,” Climatic Change 140, no. 1 (2017): 89–100. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Ramm et al., “Advancing Values-Based Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation: A Case Study from Australia,” Environmental Science and Policy 76 (2017): 113–23. [CrossRef]

- D.F. Herbst et al., “Integrated and Deliberative Multidimensional Assessment of a Subtropical Coastal-Marine Ecosystem (Babitonga Bay, Brazil),” Ocean and Coastal Management 196 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Diggon et al., “The Marine Plan Partnership: Indigenous Community-Based Marine Spatial Planning,” Marine Policy 132 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Barr, B. W., 2013. Understanding and managing marine protected areas through integrating ecosystem based management within maritime cultural landscapes: Moving from theory to practice, Ocean & Coastal Management, Volume 84, 2013, Pages 184-192. [CrossRef]

| Find Articles with these terms | "Maritime spatial planning" OR "coastal planning" OR "marine planning" OR "marine policy" OR "coastal policy" |

| Search in Title, Abstract, Keywords for… | “Underwater cultural heritage," OR "maritime cultural heritage," OR "cultural ecosystem services," OR "intangible heritage," OR "marine cultural heritage," OR "cultural values" OR "socio-cultural values" OR "tangible heritage" |

| Case-study | Significance of cultural values | Inclusion in MSP |

|---|---|---|

| Philippines, coral reefs | Coral reefs are vital for fisheries and cultural tourism. They are home to marine species, thus contributing to food security and local livelihoods. They are also linked to cultural tourism, being popular tourist destinations. | MSP in the Philippines is considering the importance of coral reefs for fisheries and cultural tourism. |

| United States, traditional fishing grounds |

Native American communities have been fishing in the same coastal/marine areas for centuries. These places are important to their culture and way of life. | MSP in the United States is considering the importance of traditional fishing grounds for Native American communities. |

| European Union, MPAs |

MSP is being used to promote sustainable fishing practices that will help ensure future food security. | MSP designates areas where fishing is restricted or prohibited (usually MPAs). This helps to protect fish stocks and ensure that they can recover, in the medium or long term. |

| Action | Method | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Protecting traditional fishing grounds | MSP can designate areas as traditional fishing grounds, where only traditional fishing methods are allowed. | This can help to protect the livelihoods of coastal communities and their cultural heritage. |

| Promoting sustainable tourism | MSP can designate areas for sustainable tourism development. | This can help create economic opportunities for coastal communities while protecting the environment and cultural values. |

| Protecting sacred sites | MSP can be used to protect sacred sites important to coastal communities. | This can help to ensure that these sites are preserved for future generations. |

| Name of regional initiative |

General aim | Cultural values related measures |

|---|---|---|

| Baltic Sea Action Plan (BSAP) | - promote sustainable development and protect the environment in the Baltic Sea. | -measures to protect coastal communities from climate change impacts. - measures to protect cultural values, such as traditional fishing grounds and sacred sites. |

| Australia, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority | -develop a marine park management plan that includes a zoning scheme to protect different reef areas for different uses, such as conservation, tourism or recreation. | - measures to protect the cultural values of the reef, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage. |

| United States, Coastal Community Resilience Initiative. | - help coastal communities to develop MSPlans to adapt to climate change and build resilience. | - provision of technical assistance and financial support to communities so as to develop MSPlans that meet their needs. |

| Topic | practice | result |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional fishing grounds | In Fiji, MSP designates traditional fishing grounds for local communities. | This is helping to protect the livelihoods of these communities and their cultural heritage. |

| Sacred sites | In the Philippines, MSP is being used to protect sacred marine sites, such as coral reefs and mangroves. | This is helping to ensure that these sites are preserved for future generations. |

| Recreational and aesthetic values | In the United States, MSP is being used to protect areas important for recreation and tourism, such as beaches, surf spots, and scenic areas. | This is helping to support the local economy and protect the cultural values of these areas. |

| Community engagement | In Canada, MSP engages with coastal communities and learns about their values and priorities. Participatory mapping is used to collect this information. | Community voices are heard in the MSP process. |

| Mapping cultural ecosystem services: | In Indonesia, participatory mapping is used to map the cultural ecosystem services important to coastal communities | This information is being used to inform MSP decisions and protect these services. |

| Mapping recreational opportunities | In the United Kingdom, participatory mapping maps recreational opportunities in coastal areas. | This informs MSP decisions and ensures that recreational needs are considered. |

| Tourism | In the Mediterranean, MSP is being used to promote sustainable tourism development in coastal areas. | This is helping to create economic opportunities for coastal communities while protecting the environment and cultural values. |

| Recreational fishing | In Australia, MSP is used to designate recreational fishing areas. |

|

| Other recreational activities | In New Zealand, MSP designates areas for other recreational activities, such as swimming, surfing, and kayaking. | This is helping to reduce conflicts between different users of marine space and ensure that everyone can enjoy the coast. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).