2. Materials and Methods

Ethics statement. Male Syrian hamsters (66 week-old, Mesocricetus auratus; breed RjHan:AURA) were bought from the Janvier Labs (SAINT BERTHEVIN CEDEX, France). We housed the hamsters under specified pathogen-free conditions, with free access to water and food. Before the immunization with non-recombinant MVA-vaccine or MVA-ST vaccine, the hamsters adapted to our stables for at least one week. Our hamster studies fully meet the requirements of the European and national regulations for animal experimentation (European Directive 2010/63/EU; Animal Welfare Acts in Germany) and Animal Welfare Act, approved by the Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit (LAVES) Lower Saxony, Germany). After SARS-CoV-2 challenge, the animals were housed in individually ventilated cages (IVCs; Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy) in approved BSL-3 facilities. All animal and laboratory work involving infectious SARS-CoV-2 was done and facilitated in a biosafety level (BSL)-3e laboratory and facilities at the Research Center for Emerging Infections and Zoonoses, University of Veterinary Medicine, Hannover.

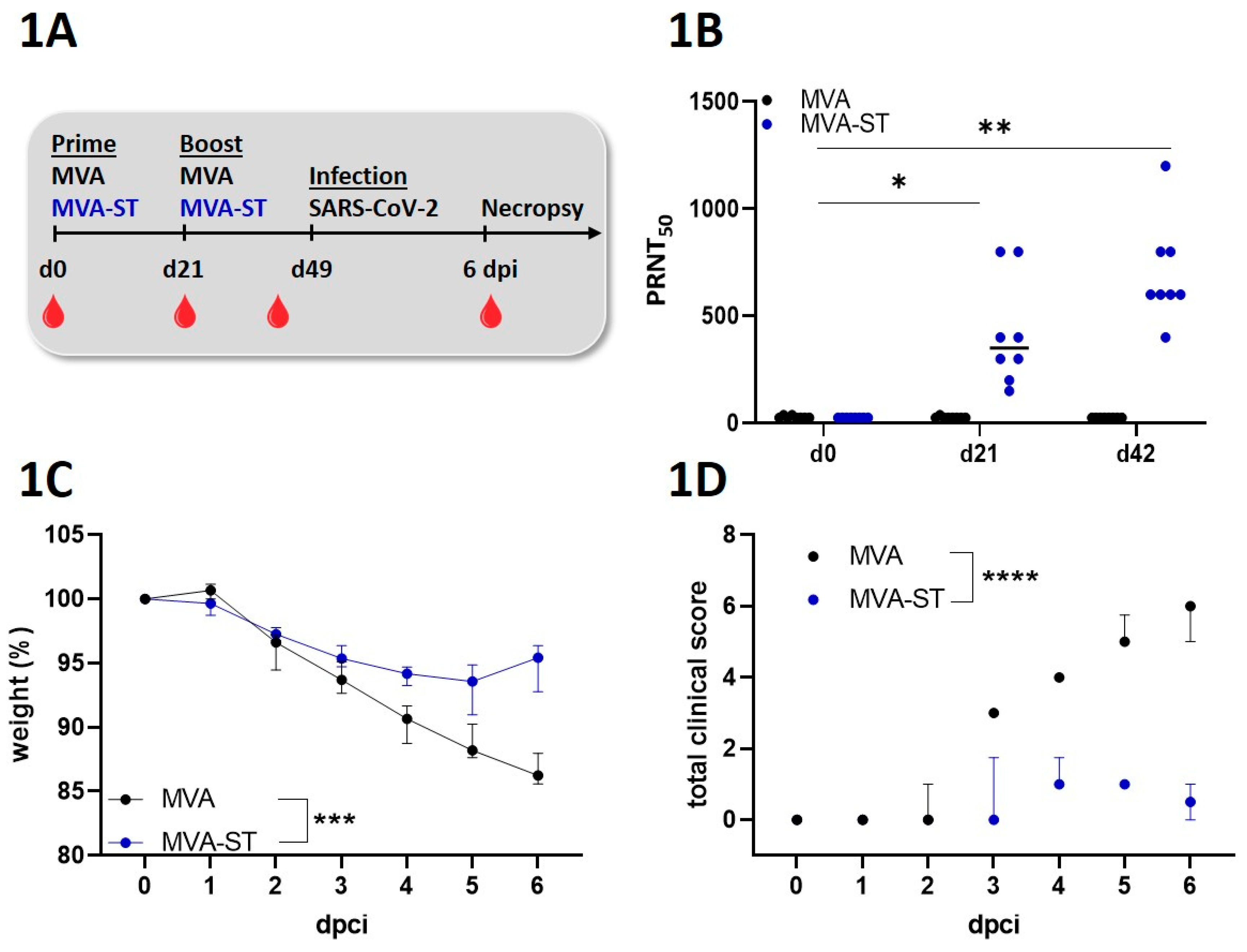

Immunization experiments in hamsters. Male Syrian hamsters (66 week-old, Mesocricetus auratus; breed RjHan:AURA) were immunized with 108 PFU recombinant MVA-ST or empty-MVA-vector control intramusculary into the quadriceps muscle of the left hind leg. Second immunization (Boost-immunization) was applicated 21 days later. We closely observed and monitored the hamsters after the immunizations for well-being, health constitution and clinical signs as represented in a clinical score. We also monitored the body weights daily. For further analysis, we collected blood at different time points (days 0, 21, 42 and 55) after the immunization. Serum was prepared by centrifugation of the coagulated blood at 1300 × g for 5 min in serum tubes (Sarstedt AG&Co., Germany). Serum samples were then stored at -80 °C until further evaluations.

SARS-CoV-2-infection experiments in Syrian hamsters. We performed challenge-infection by the intranasal route with 1x104 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 (Isolate Germany/BavPat1/2020, NR-52370) received from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH under anesthesia. After respiratory challenge the hamsters were monitored at least twice per day for well-being, health constitution and clinical signs using a clinical score sheet by allocating to one of the following categories of COVID-19 disease specific symptoms: Cardiovascular system, fur/ skin condition, lower respiratory tract, upper respiratory tract, environment social behaviour/ general condition/ locomotion and neurological scoring. Body weights were checked daily.

Virus. SARS-CoV-2 (Isolate Germany/BavPat1/2020) received from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH was amplified in VeroE6 cells (ATCC #CRL-1586) in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) including 2% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine at 37°C. Experiments including SARS-CoV-2-infection were conducted in biosafety level-3 laboratories at the RIZ, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany. The recombinant MVA candidate vaccine expressing a prefusion-stabilized version of SARS-CoV-2 spikeprotein (MVA-ST) was generated as previously described [

10]. MVA-ST has been amplified on DF-1 cells and purified by sucrose-gradient as previously described [

10].

Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50). Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT50) were done to evaluate the titers of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in serum samples. SARS-CoV-2 (Isolate Germany/BavPat1/2020) obtained from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH was used for the infection of VeroE6 cells in the PRNT50 assay. Heat-inactivated serum samples were plated as duplicates in 2-fold dilutions in 50 µl DMEM on 96-well-plates. 50 μl of SARS-CoV-2 (600 TCID50) was added per well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation the mixtures was placed on VeroE6 cells using 96-well plates and incubated for 45 min. 100 µl DMEM mixed 1:1 with Avicel RC-591 (Dupont, Nutrition & Biosciences) was layered on each well and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Finally, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde/PBS for further staining. For this, a polyclonal rabbit antibody targeting the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (clone 40588-T62, Sino Biological) was used. A secondary peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Dako, Agilent) was used to develop a signal after adding a precipitate forming TMB substrate (True Blue, KPL SeraCare). Counts of infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 was measured with the ImmunoSpot® reader (CTL Europe GmbH). Using the the BioSpot™ Software Suite the serum neutralization titer (PRNT50) was calculated. For this, the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution leading to a reduction of >50% of the plaque formation by SARS-CoV-2 infection was used.

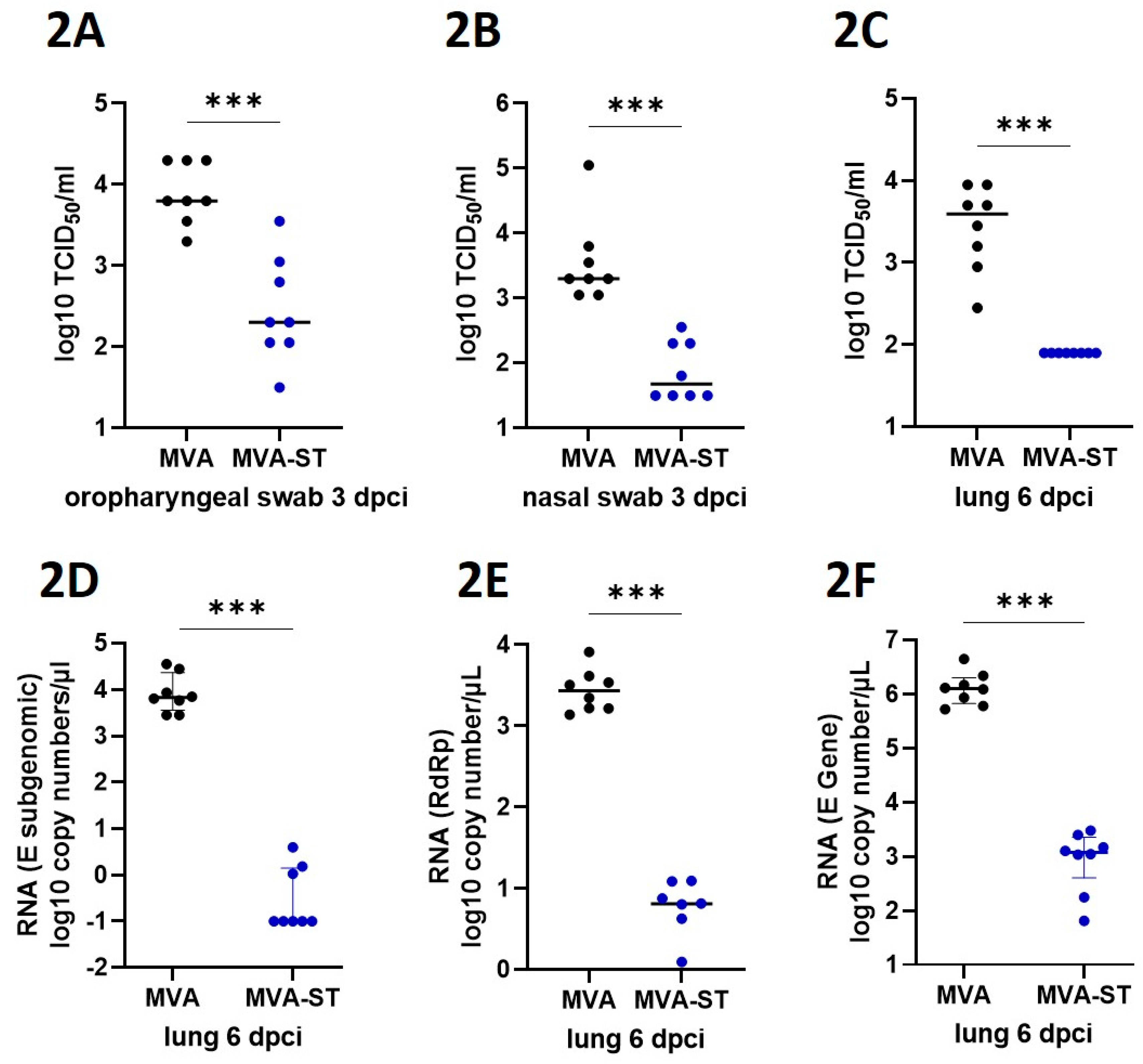

Measurement of viral burden. To analyze the viral load in nasal or oropharyngeal swabs, swabs were taken either from the nose or from the oropharynx by rotating the tip of the swabs. After sampling, swabs were then dissociated and lysed in 1ml DMEM containing P/S (penicillin and streptomycin, Gibco). To analyze the viral load in the lungs of infected hamsters, tissue samples were taken after euthanasia and further prepared by homogenization in 1 ml DMEM containing P/S (penicillin and streptomycin, Gibco). Homogenization was performed with the TissueLyser-II (Qiagen) and the homogenate was stored at -80°C until further use. To determine the titers of infectious SARS-CoV-2, lung-homogenates or swab lysates, in DMEM containing 5% FBS, were incubated in serial 10-fold dilutions on Vero cells in 96-well-plates. After four days of incubation at 37°C, the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50 units / ml) was calculated using the Reed-Muench method based on cytopathic effects in the cells. For statistical analysis, the data points of samples which did not induce cytopathic effects, were changed to half of the detection limit. To determine levels of viral RNA of SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs, RT-qPCR (quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR) analysis targeting different genes of SARS-CoV-2 were conducted. Using the KingFisher Flex, RNA was extracted from lung tissue samples with the NucleoMag RNA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For SARS-CoV-2 RNA amplification, the Luna® Universal Probe One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (NEB #E3006, New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) was used in a CFX96-Touch Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The RT-qPCR assay specific for the RdRp gene of SARS-CoV-2 and recommended by the WHO, were used: SARS-2-IP4, forward primer (5′- GGT AAC TGG TAT GAT TTC G -3’), reverse primer (5′- CTG GTC AAG GTT AAT ATA GG-3’) and probe (5’-TCA TAC AAA CCA CGC CAG G-3’ [5']FAM [3']BHQ-1)]. The RT-qPCR assay specific for the subgenomic E of SARS-CoV-2 used the following primers: forward primer (5′ ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA -3’), reverse primer (5′ CGATCTCTTGTAGATCTGTTCTC -3’) and probe (5’ ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG -3’ [5']FAM [3']BBQ]. The RT-qPCR assay specific for the E gene of SARS-CoV-2 used the following primers: forward primer (5′ ACAGGTACGTTAATAGTTAATAGCGT-3’), reverse primer (5′ ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA-3’) and probe (5’ ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG-3’ [5']FAM [3']BBQ]. The PCR program included reverse transcription at 50˚C for 10 min; denaturation at 95˚C for 1 min; 44 cycles of 95˚C for 10 sec (denaturation), and 56˚C for 30 sec (annealing and elongation). The relative fluorescence units (RFU) were measured at the end of the elongation step. The sample Ct value was correlated to a standard RNA transcript and the quantity of viral RdRp copy numbers per µl of total RNA was calculated.

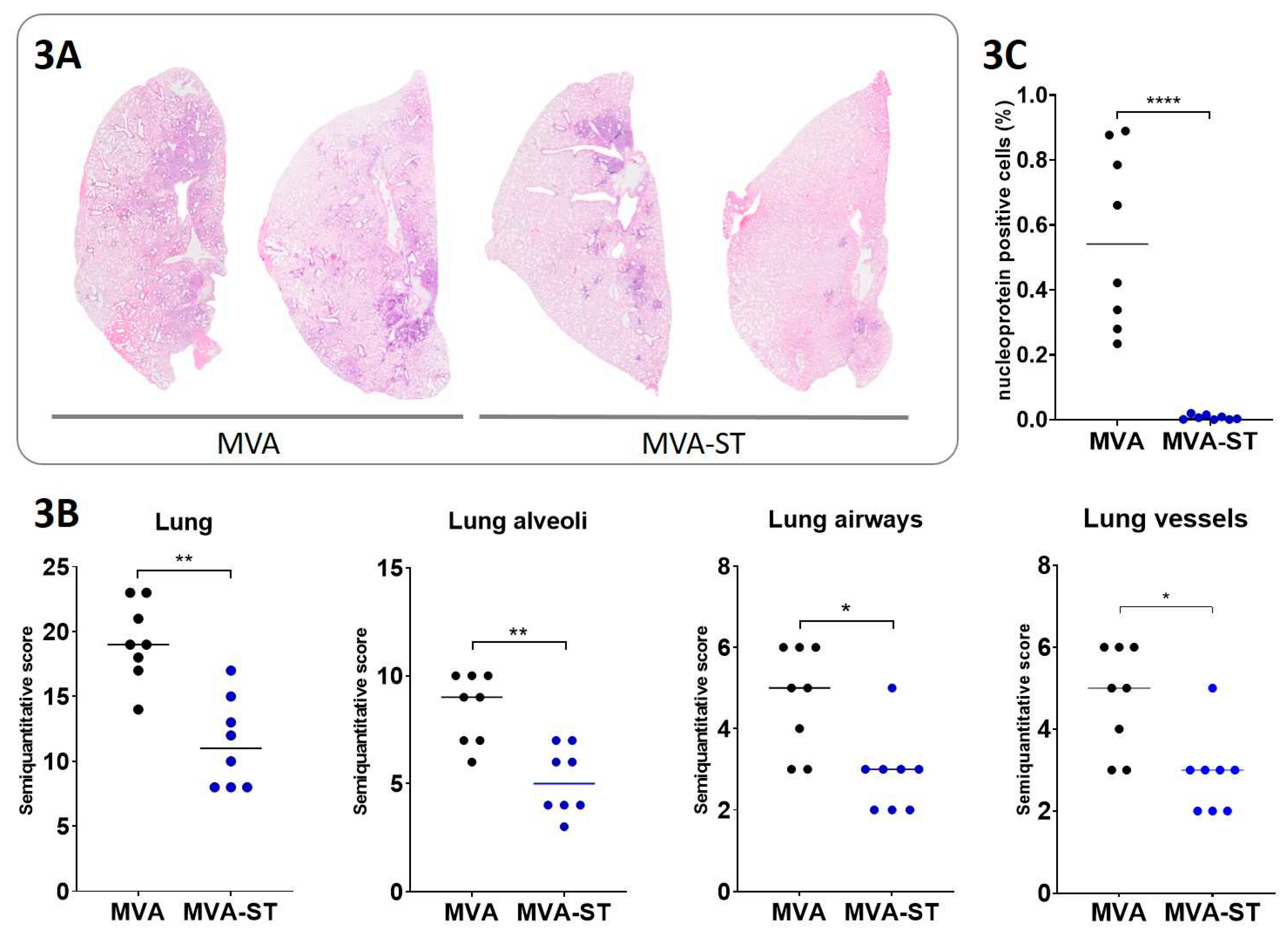

Histological evaluation of lung pathology in hamsters. Injection and plunging of 10% buffered formalin in the lung was done for fixation purposes. Left lung lobe tissue samples were further embedded in paraffin and 2-3 µm thick sections were generated. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was performed for the evaluation of lesions in the lung. Analysis was done blinded with a semi-quantitative scoring system. Briefly, the evaluation included assessment of alveolar lesions (inflammation, regeneration, necrosis/desquamation and loss of alveolar cells, atypical large/syncytial cells, intraalveolar fibrin, alveolar edema, hemorrhage), airway lesions (inflammation, necrosis, hyperplasia) and vascular lesions (vasculitis, perivascular cuffing, edema, and hemorrhage). The total scores reflect the sum of all scores in the respective lung anatomical compartments. Details on the scoring system have been described previously [

11].

Immunohistochemistry targeting the Nucleocapsid of SARS-CoV-2. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue samples were stained using a monoclonal mouse antibody (Sino Biological, 40143-MM0) against the nucleoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 and the Dako EnVision+ polymer system (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions) as described previously [

12].

To quantify SARS-CoV-2 NP immunolabeled cells in pulmonary tissue, slides were digitized using a slide scanner (Olympus VS200 Digital; Olympus Deutschland GmbH). QuPath (version 0.3.1) was used to perform Image analysis [

13]. Detection of lung tissue was performed automatically using digital thresholding. Images of whole slides of the entire left lung were evaluated. Blood vessels as well as artifacts were subtracted from the total lung tissue as they were indicated as ROIs. Automated positive cell detection was used, as previously described [

14], to quantify the immune-stained cells in the lung tissue. This was based on marker-specific thresholding parameters.

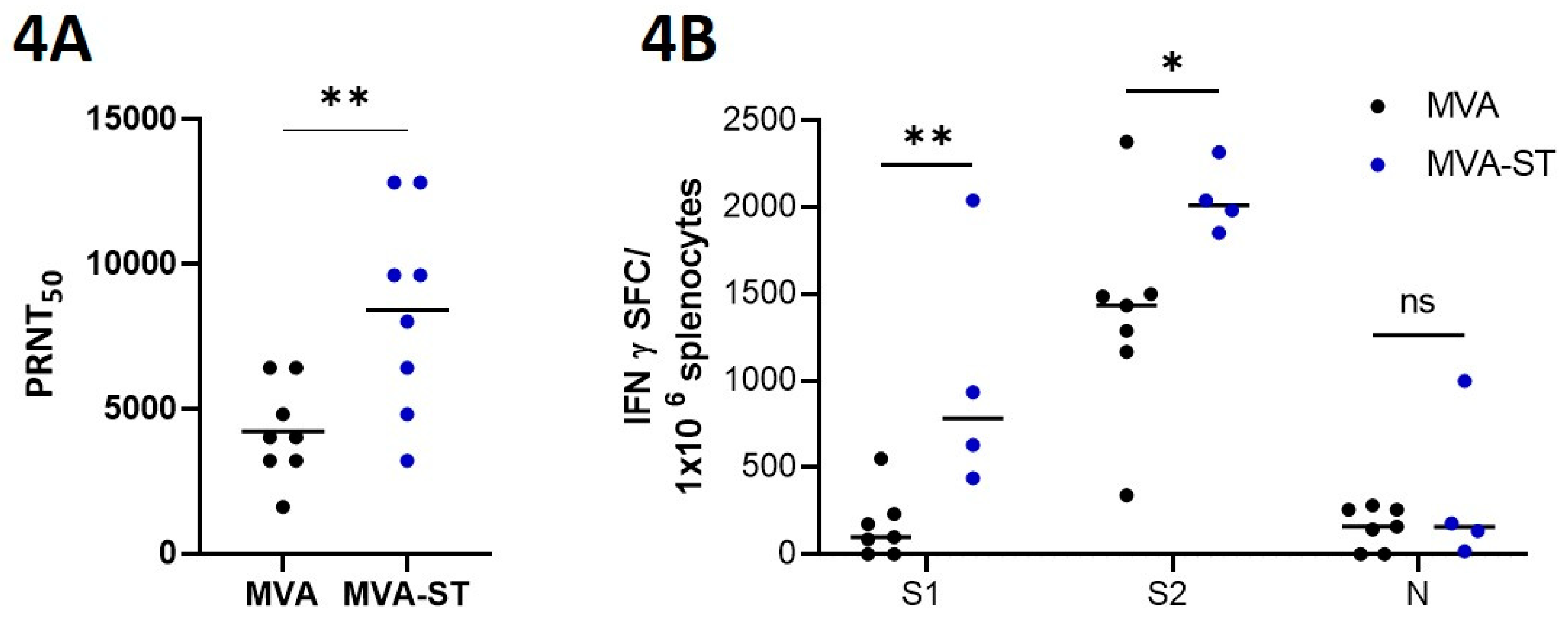

Enzyme-linked Immunospot (ELISpot). Hamsters were euthanized on day 6 after challenge infection and splenocytes were isolated immediately. For this, spleens were smashed on a 70-µm strainer (Falcon®, Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) and flushed and solved with RPMI-10 (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1% HEPES; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Lysis of red blood cells were conducted with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). After one washing step, cells were resuspended in RPMI-10. 2x105 splenocytes were counted with the MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and seeded per well in 96 well round bottom plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). For stimulation, three different peptide pools of overlapping peptides obtained by JPT Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany) were used. Each peptide consists of 15 amino acids (15mers) overlapping in 11 amino acids. Two of the peptide pools consisted of 157 and 158 overlapping peptides (1µg peptide/mL RPMI 1640) comprising the whole spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. One additional peptide pool was used for stimulation, which consists of 59 overlapping peptides (1 µg peptide/mL RPMI 1640) comprising the whole nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 (BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH). This antigen is not present in the evaluated vaccine. Positive and negative controls were created by stimulation of the cells with phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin (PMA, SIGMA-ALDRICH, Taufkirchen, Germany) as well as the use of non-stimulated cells. Plates with PVDF membranes (Mabtech, Nacka, Sweden) were coated with a hamster specific anti- IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (Mabtech, Nacka, Sweden). Cells were then placed on the coated plates and incubated for 36 h at 37°C. The inoculum was removed and biotinylated anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody was added. After incubation, streptavidin ALP followed by BCIP/NBT-plus substrate was added. Washing steps were done in between all steps as well. The generated spots were scanned and counted with the automated ELISpot Reader ImmunoSpot S6 ULTIMATE UV Image Analyzer (Immunospot, Bonn, Germany) and further analyzed with the ImmunoSpot 7.0.20.1 software.

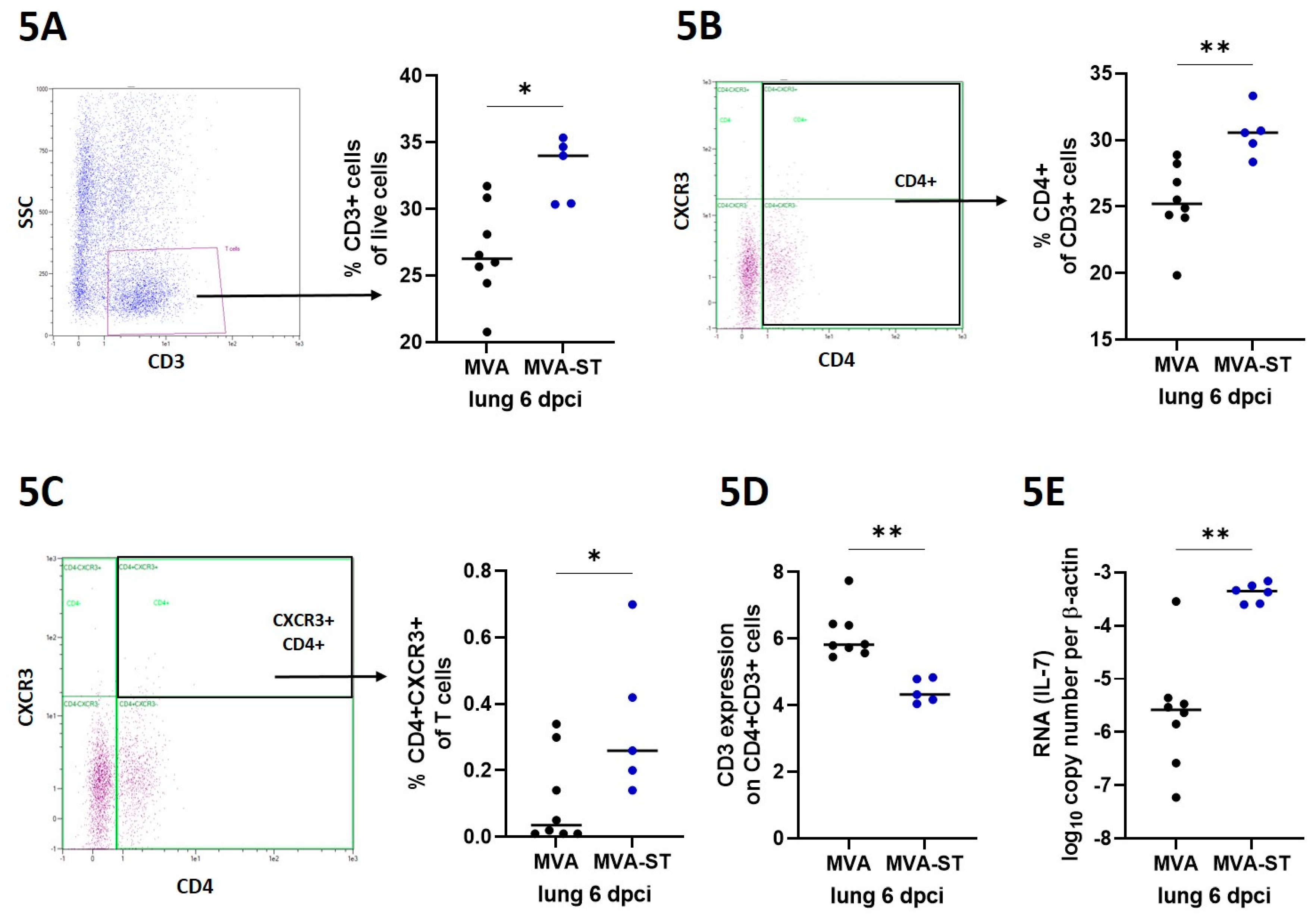

Flow cytometry. For phenotype characterization, cells were isolated from lungs via digestion using RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 1 mg/ml Collagenase (GENAXXON bioscience GmbH, Ulm) and 0,5 mg/ml DNase (Roche, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt) for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Subsequently, digested lungs were smashed with scissors and flushed with RPMI-10 (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) through a 70-µm strainer (Falcon®, Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Incubation with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) lysed red blood cells. After a washing step, cells were resuspended in RPMI-10 medium. The cells were counted with the MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and dead cells were visualized by staining 4x105 lung cells with LIVE/DEAD fixable Near IR stain kit (InvitrogenTM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions followed by fixation using 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 20 minutes. 2x105 cells were stained with antibodies against CXCR3 (RRID: AB_2743928), CD4 (RRID: AB_464894) and CD3 (RRID:AB_10841760) in a total volume of 200 µl for 30 minutes. After washing, cells were measured using the MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Analysis of IL-7 by Real-time-PCR. Extracted RNA from lung tissue samples was amplified in a CFX96-Touch Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad) using the commercially available Luna® Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (NEB #E3005, New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The RT-qPCR assay specific for the hamster IL-7 used the following primers: forward primer (5′-ATCCAAGCCACAAAAATAAAGCC-3’) and reverse primer (5′-TTTCTTGCTGTCACTGCTTTG-3’). To normalize values, ß-Actin was used as housekeeping gene using (5′-CCAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAG-3’) as forward primer and (5′-ATGGCTACGTACATGGCTGG-3’) as reverse primer.

The PCR program included reverse transcription at 55˚C for 10 min; denaturation at 95˚C for 1 min; 44 cycles of 95˚C for 20 sec (denaturation), and 56˚C for 30 sec (annealing and elongation). The relative fluorescence units (RFU) were measured at the end of the elongation step. Amount of IL-7 relative to the housekeeping gene was calculated using the Ct method.

Statistical analysis. Data were prepared using GraphPad Prism 9.0.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego CA, USA). Data sets were analyzed for normal distribution using D’Agostino & Person test or Shapiro-Wilk-test. Normally distributed data were analyzed for differences using t-test or 2-way-ANOVA and expressed with mean. Not-normally distributed data were analyzed for differences using Mann-Whitney-test and Friedman test and expressed as median. A P value < 0.05 indicates the threshold for statistical significance.

4. Discussion

Immunosenescence is a known problem for successful vaccination in elderly people [

16]. In this study, we used 66-week-old hamsters, which correlates to about 65 years in human age [

17]. In agreement with data from previous studies evaluating the effects of COVID-19 vaccinations in different human age groups [

18], we observed altered protection in aged MVA-ST-vaccinated hamsters compared to the equivalent adult hamster model [

10]. Our results demonstrated that the immunogenicity and protective outcome of MVAT-ST-immunization in the old hamsters was different from the MVA-ST immunization in normal aged hamsters. Here, we confirmed significant immunogenicity and efficacy of MVA-ST-prime-boost immunizations [

10]. In the aged hamsters, following infection-challenge after MVA-ST vaccination, we detected minimal disease outcome, with marginal body weight loss, clinical symptoms and viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract. This is in line with data from humans when break-through infections with mild clinical disease have been confirmed in vaccinated people with a mean age of 71.1 [

19,

20]. An effect of immunosenescence is also seen for the control-aged hamsters, where we observed more severe SARS-CoV-2 disease outcomes compared to adult hamsters [

10]. We also detected more severe lung pathology with massive extents of alveolar inflammation and damage, confirming other studies characterizing SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in aged hamsters [

4,

5,

6]. Similarly, in elderly people, SARS-CoV-2 infection often results in severe disease with more pronounced lung pathology. In addition to minimal clinical symptoms and reduced viral shedding from the upper respiratory tract, we detected no viral load and significantly reduced levels of lung damage in aged MVA-ST-vaccinated hamsters, indicating a robust protective capacity.

MVA is an attenuated, replication deficient candidate vaccine with a well-established safety profile and excellent immunostimulatory effects. This is already confirmed as a smallpox vaccine where MVA has been successfully administered to persons at risk, e.g. with atopic dermatitis or infected with HIV [

21,

22,

23]. Thus, MVA seems excellently suited to overcome the limitations of vaccination in the elderly. This has already been successfully confirmed for an MVA-based vaccine against influenza in a clinical phase I study [

24].

In line with clinical data from Flu vaccine development, we confirmed the suitability of our MVA-ST vaccine in hamsters as a surrogate model for COVID-19 in humans. This was emphasized by the strong activation of neutralizing antibodies in MVA-ST-vaccinated animals even before challenge infection. After SARS-CoV-2 challenge, we also detected SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies in control animals despite the absence of obvious protective efficacy, possibly resulting from fulminant viral infection in the upper respiratory tract. Another hypothesis is that these increased titers of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies are involved for the outcome of severe COVID-19 disease. This has been demonstrated in elderly people with more severe disease who exhibited higher antibody reactivity [

25]. In this context, cellular immunity correlated with more robust and solid protection independent of humoral immunity [

26].

Notably, compared to the control hamsters, we demonstrate that MVA-ST-vaccinated elderly hamsters mount robust activation of T cells. Especially within the lung, the main target organ for COVID-19, we detected significantly increased titers of activated CD4+ T cells, as seen for CXCR3+ cells. Such strong immunostimulation is a well-known characteristic of MVA-based vaccines and mainly correlates with a potent activation of innate immune signaling leading to chemokine and cytokine induction, generating an optimal immunological milieu for antigen-specific immunity [

27]. To support this, MVA-ST-vaccinated hamsters mounted significantly increased levels of IL-7. Diminished activation of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-7 has been confirmed to be involved in the outcome of immunosenescence [

28]. Advanced activation of the innate immunity might explain the improved activation of antigen-specific T cells in MVA-ST-vaccinated animals. This is further confirmed not only by increased levels of CD4+ T cells lacking TCR on the surface, indicating activation of antigen-specific T cells [

29], but also when we detected significantly increased levels of S1- and S2-specific T cells in the spleens of MVA-ST-vaccinated hamsters. Future studies will be of interest to characterize the role of these SARS-CoV-2 S-specific T cells in more detail concerning the outcome of infection and/or vaccine induced protection.

In summary, our aged-hamster model confirmed the robust activation of SARS-CoV-2-specific immunity after MVA-ST-immunization, likely involved in protection against severe clinical disease outcome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V., S.C.; methodology, A.V., S.C., L.M.S., F.A.; formal analysis, A.V., S.C., L.M.S., F.A., C.M.z.N., T.T., A.T., M.C., W.B., G.S.; investigation, A.V., S.C., L.M.S., F.A., C.M.z.N., T.T., A.T., M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V., S.C., L.M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.V., S.C., L.M.S., L.M.S., F.A.; project administration, A.V., funding acquisition, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.