1. Introduction

Forest represents around 39% of the land cover in Europe [

1], with a highly variable distribution across the continent [

2,

3]. Countries in Northern Europe generally have large forested areas, while regions in Central-East and Central-West Europe have the lowest percentages of forest area [

4]. Overall, Europe has experienced an increase in forest area in the past few decades as a result of additional afforestation programmes and natural regeneration initiatives on less productive lands [

5,

6].

Forests provide a wide range of ecosystem services, such as climate regulation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation and water regulation besides being the focus of livelihoods for millions of people worldwide, with important economic outcomes, such as wood production, non-wood forest products, and ecotourism [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In Europe, the forest sector contributes for approximately 1% of the overall Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and employs closely to 2.6 million people [

12]. Climate changes, the expansion of the agriculture dedicated areas and the livestock grazing pressure, the intensive exploitation of forests and frequent wildfires have been causing additional damages to forests [

13]. These major challenges intensify deforestation and forest degradation, significantly decreasing their potential benefits to the planet while increasing the unwanted greenhouse gas emissions, loss of biodiversity, and degradation of soil quality [

14,

15].

Sustainable forest management and its relationship to most relevant worldwide goals, such as a low-carbon economy, biodiversity conservation and the mitigation of climate change, has boosted the growing interest in certified forest-based products [

16,

17]. This has been driven mainly by consumer awareness and demand for sustainable products, as well as by public policies that promote sustainable procurement practices for enhancing forest ecosystem services and related environmental benefits, along with the increasing need for design and production of renewable biomaterials [

18,

19]. In response to this demand, many companies have now adopted sustainable sourcing policies that require them to rethink the whole value chain and products from certified forests [

20].

Forest certification was established as a tool to promote sustainable forest management practices and to reduce the negative impacts of exploiting forests and their ecosystems [

6,

21]. The sustainable forest management framework should contribute to the global balance of ecological, economic, and social needs by making sure that forest resources are managed in a way that satisfies current demands without endangering the needs of future generations [

22,

23]. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of the Forest Certification (PEFC) are the two main certification schemes, certifying both forest management and the forest chain of custody [

6,

16,

24]. The FSC, established in 1993, was the first certification scheme to set standards for responsible forest management and to certify forests that meet those standards [

25]. The PEFC provides a framework for national forest certification standards [

26], allowing national structures to develop their own guidelines reflecting their local conditions and priorities. Additionally, forest management in Europe is governed by a range of policies, laws, and guidelines that aim to promote sustainable forest management. The European Union (EU) has developed a comprehensive framework for forest management through its Forest Strategy, adopted in 2021. This strategy outlines a set of objectives and actions that aim to promote sustainable forest management and ensure that forests continue to provide a wide range of environmental, social, and economic benefits [

27]. Several of these policies are grounded on the notion that the investment in forests has the potential to provide financial returns while promoting sustainable forest practices [

28]. It is this potential valorization and financial return that is yet undefined and that needs to be further validated.

The forest sector must be sustainable and resilient in all of its aspects including economically, and the certification procedures comprise additional costs to producers and forest managers [

19]. An international commitment to sustainability has been established based on the concept that sustainable development represents an urgent need that should be aimed and accomplished by all countries through the coordinated efforts of a variety of individuals and organizations [

23]. As forests play an essential role in sustainable development and have a direct impact on the carbon cycle, climate change, and biodiversity [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], they were considered in the original definition of sustainability, and their impacts were integrated into sustainable indicators and metrics [

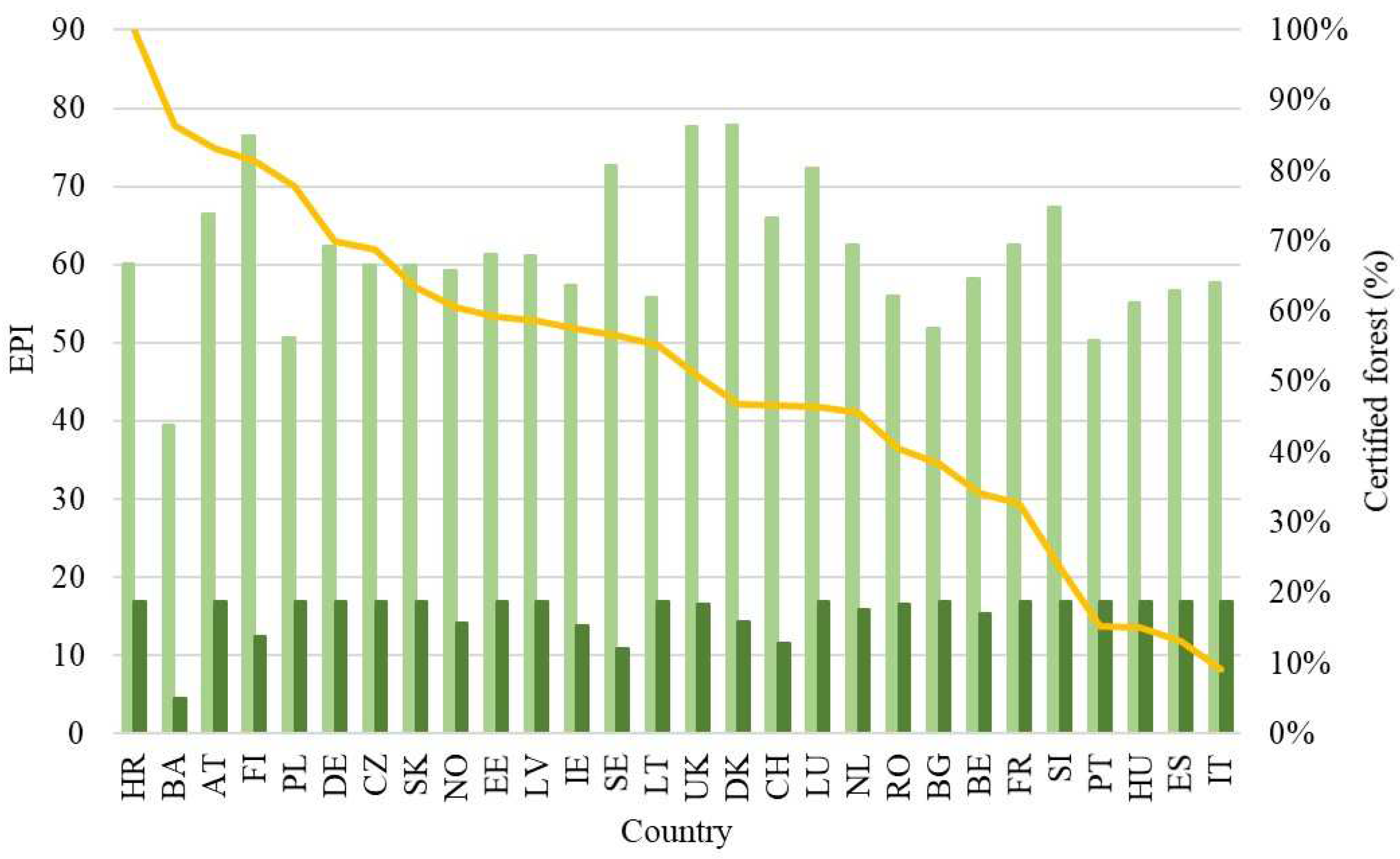

29]. The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) aims to measure the environmental health and ecosystem vitality at the national level for hierarchical purposes [

30] and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) give focus to the social, economic, and environmental sustainability [

31]. The emphasis on sustainability addressed by EPI and SDG should be mandatory for all nations and not just those in developing regions.

The potential for guiding society towards a more sustainable future relies on scientific and technological advancement. Scientific findings are essential for promoting forestry-related knowledge and innovation. They offer information on the novel management techniques and the most sustainable forest practices [

30]. Quantifying the economic, environmental, and social advantages of certification may inspire forest owners to pursue certification and investors to finance certified industries and products. The impact of research on investment choices in forest related topics, across Europe, can be better understood by examining the relationship between the number of scientific publications focused on forest certification and the level of investment in the sector by country. Scientific publications serve as valuable sources of information and guidance for policymakers, investors, and practitioners involved in forestry [

30], delivering evidence-based research, case studies, and practical recommendations. Integrating scientific research with data from the forest certification process and the economy of the sector will help to clearly define the risks, advantages, and potential for attracting additional investments and market expansion. There is a significant call from the forest sector for improving financing to address the lack of funds for biodiversity protection and sustainable land management [

32]. Investment patterns are still favoring activities that are economically relevant but not always environmentally sustainable [

33].

By studying and disseminating new knowledge on the benefits and potential risks of investing in forests, as well as good practices in their sustainable management and ecosystems conservation for the greater good, scientific publications may play a crucial role in encouraging and informing political and investment decisions. The aim of this study is to provide an analysis of the levels of forest certification across Europe and to identify key factors influencing the relationship between forest certification, research, and investment or economic valorization of the forest-related markets. In this context, the present study explores the available information from technical reports, policy documents, and other reliable public data sources associated with forest certification and related economic indicators by country in Europe and infers the impacts they have depending on the types of forest management and certification schemes in the different member states. This research also looks at the relevance of scientific studies on this topic and its potential relationship with the economic impact of forest certification on each country. The relevance of the scientific research was assessed by the number of studies with specific keywords related to this topic that were retrieved from the Scopus database for each European nation.

4. Discussion

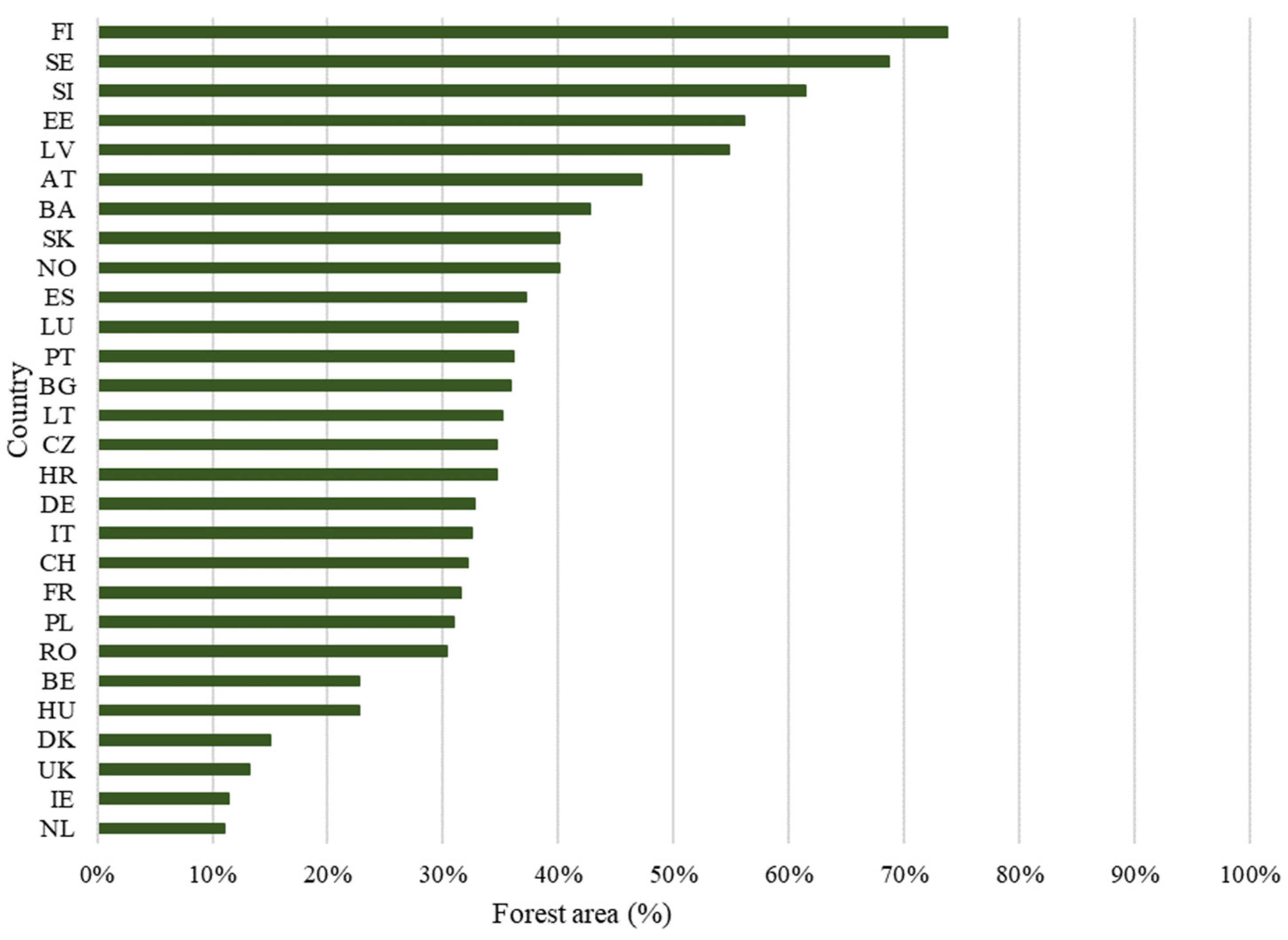

The forest covered area varied greatly across the European nations investigated, with countries like Finland and Sweden having nearly 70% of their land cover forested, while Netherlands and Ireland presented circa 11% of forest area. This fact is not only related to a country geographical condition but also is an indicator of different types of forests, distinct management approaches, and national forest policies [

39]. However, despite variations in forest coverage across countries, statistics showed that between 2000 and 2018, the quality of more than 60% of the forest in Europe has increased [

3]. Forest certification has made significant progress in Europe in promoting sustainable forest management practices [

21], a concept that has been growing in acceptance and popularity in both national forest plans and international forest policy [

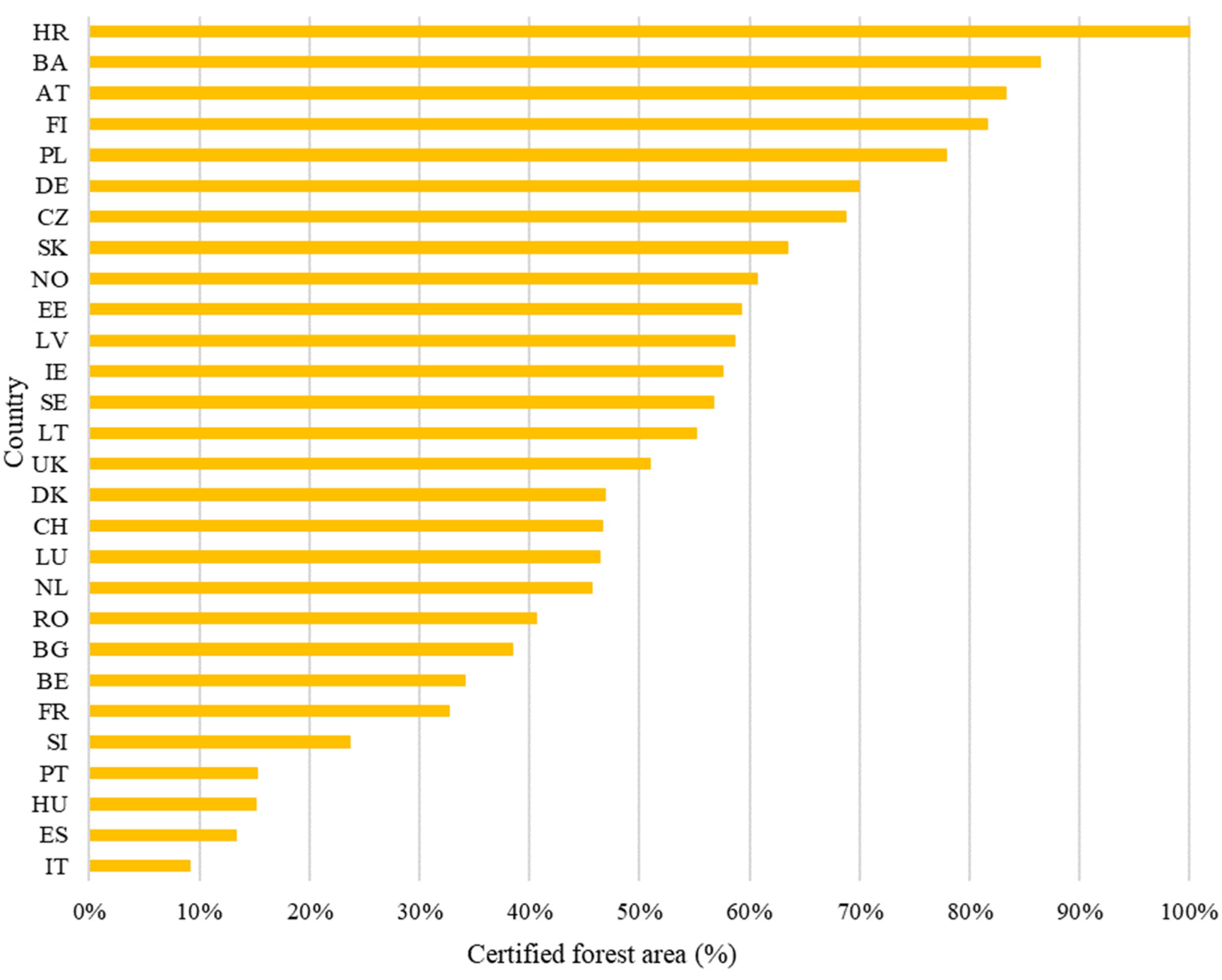

40]. Our results demonstrated that the pattern observed within European countries in relation to forest coverage is not yet fully reflected in the proportion of certified forest. Even though Finland had the highest percentage of forest area and more than 80% of certified forests, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Austria all had even higher certification rates.

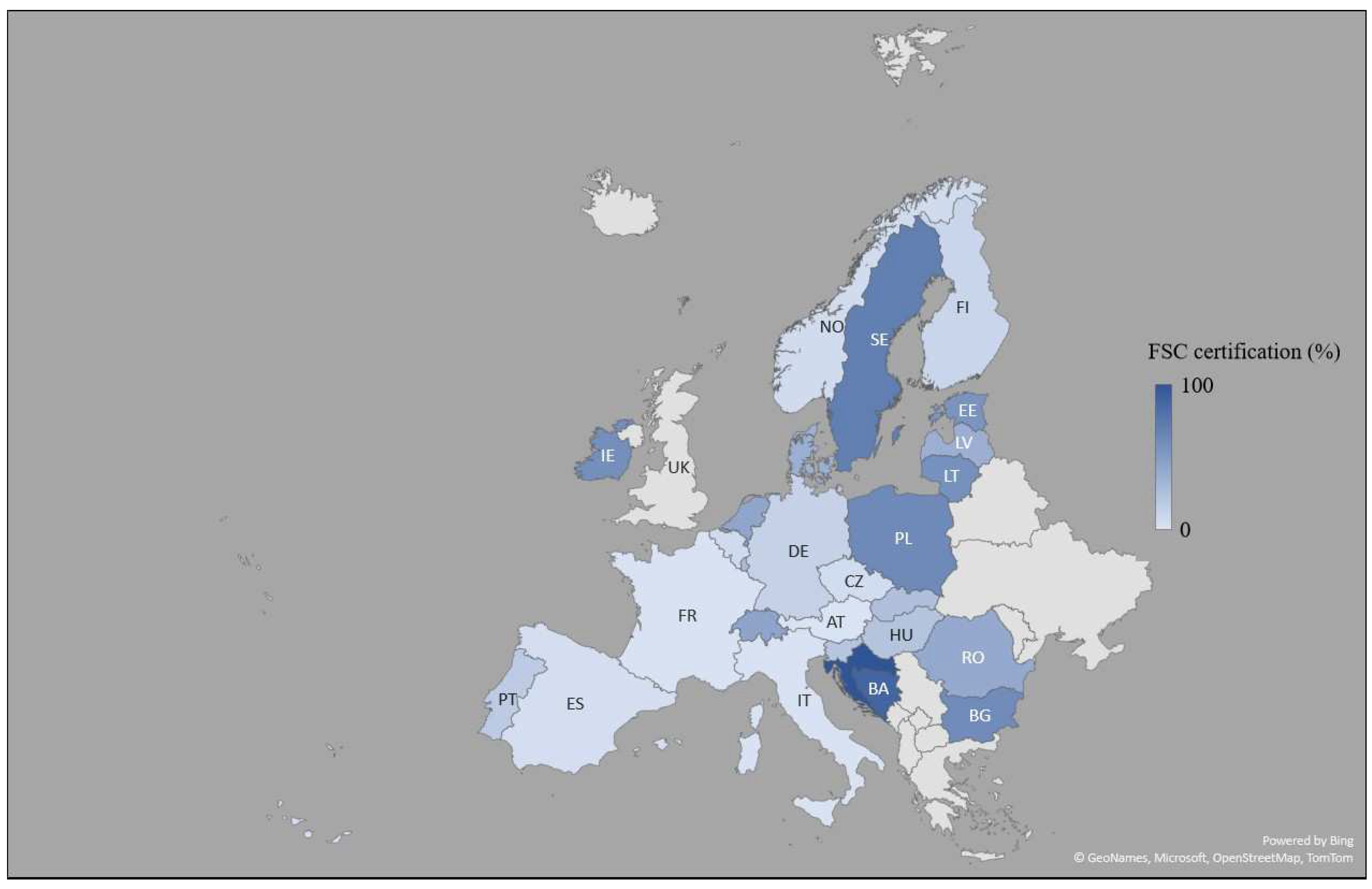

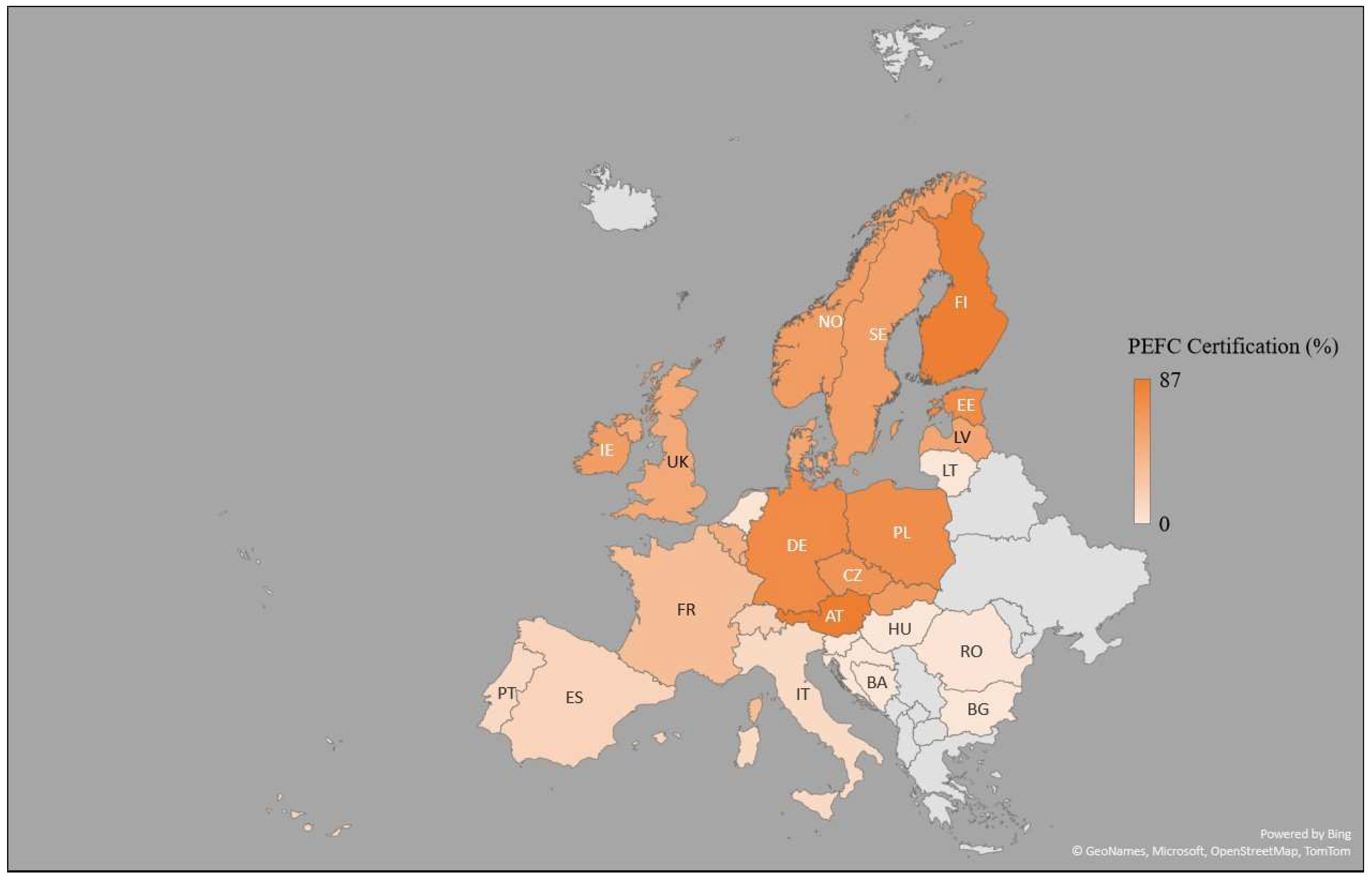

More than 98 million hectares of the European forest, representing around 50% of the total forest area in Europe, are certified by one or both of these two certification schemes, FSC and PEFC [

35,

36], with PEFC certifying more area than FSC within the analyzed countries. Results from this work indicated that few countries were certified by the two organizations at equivalent rates, most of the countries presented a prevalence of one of the certification schemes. This last result is in agreement with the findings reported by other authors [

6,

41,

42]. Countries continue to have an evident preference for one of the certification standards (e.g., Austria and Finland preferring PEFC, and Croatia preferring FSC), other countries like Ireland lost that partiality to have an almost equal percentage of forest certified by both organizations. Ireland and Portugal who, according to [

6], had no forest certification by PEFC now presented forest certified by this organization (59% and 10% respectively). The adequacy of FSC and PEFC standards depends on the environmental and socioeconomic context of a given nation or sector, and of the stakeholder perspectives on how to best address the main obstacles of forest certification [

42]. In countries like Croatia, where the majority of the forest is managed by the state [

43], FSC certification is frequently considered as a means of validating the quality and competence of state forest management organizations [

44], justifying the high amount of certified forest area under this standard [

6]. On the other hand, the external credibility of companies with greater efficiency and economic profitability, as well as the access to international markets, have been significant drivers of entry into PEFC certification [

20,

45] for European countries. This tendency to increase the presence of both standards in many European countries is often a requirement to have access to international markets and a response of companies to the market trends, as the two schemes have no mutual recognition [

6,

20,

22] and different consumer markets may prefer different certification brands.

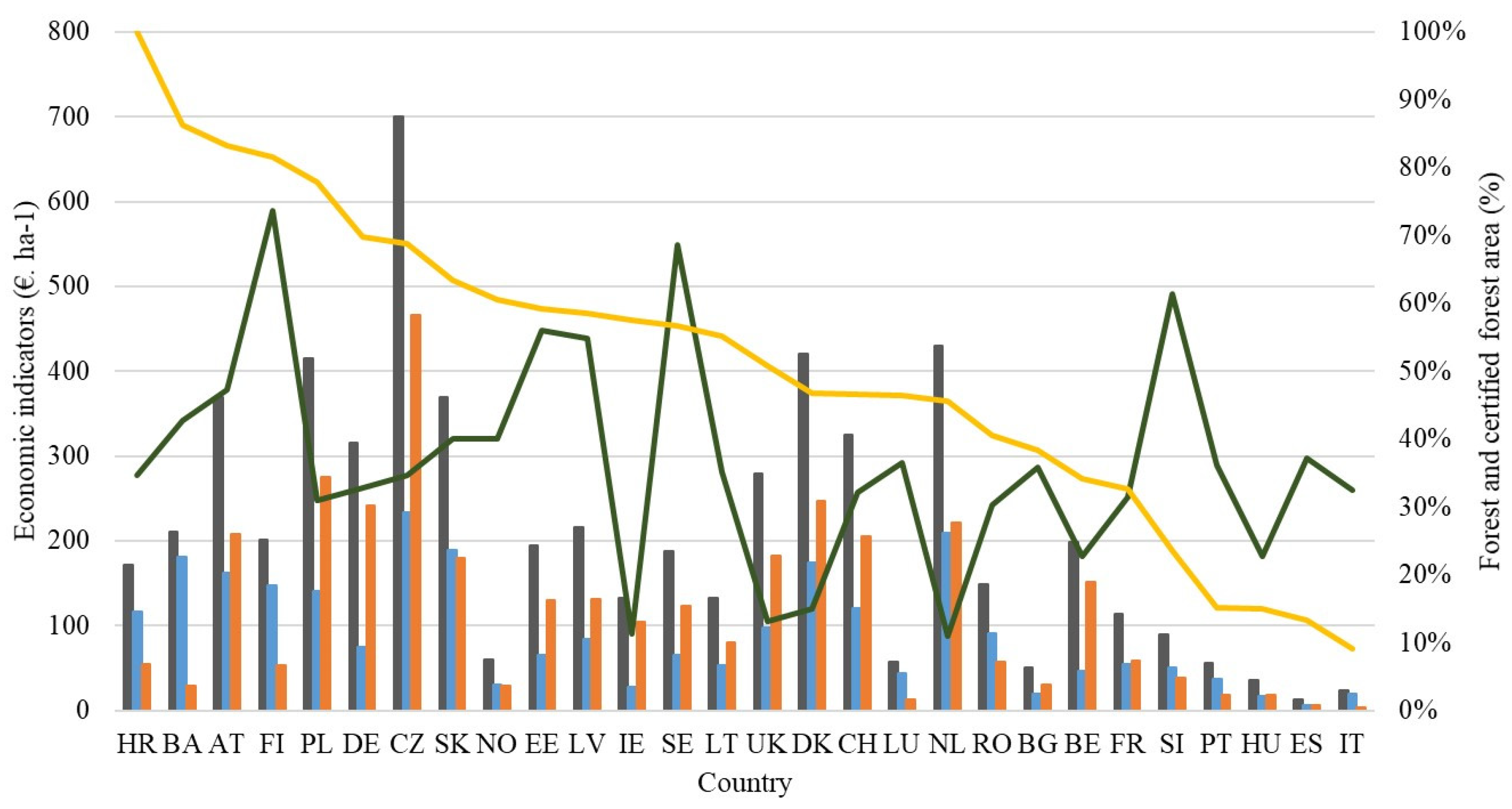

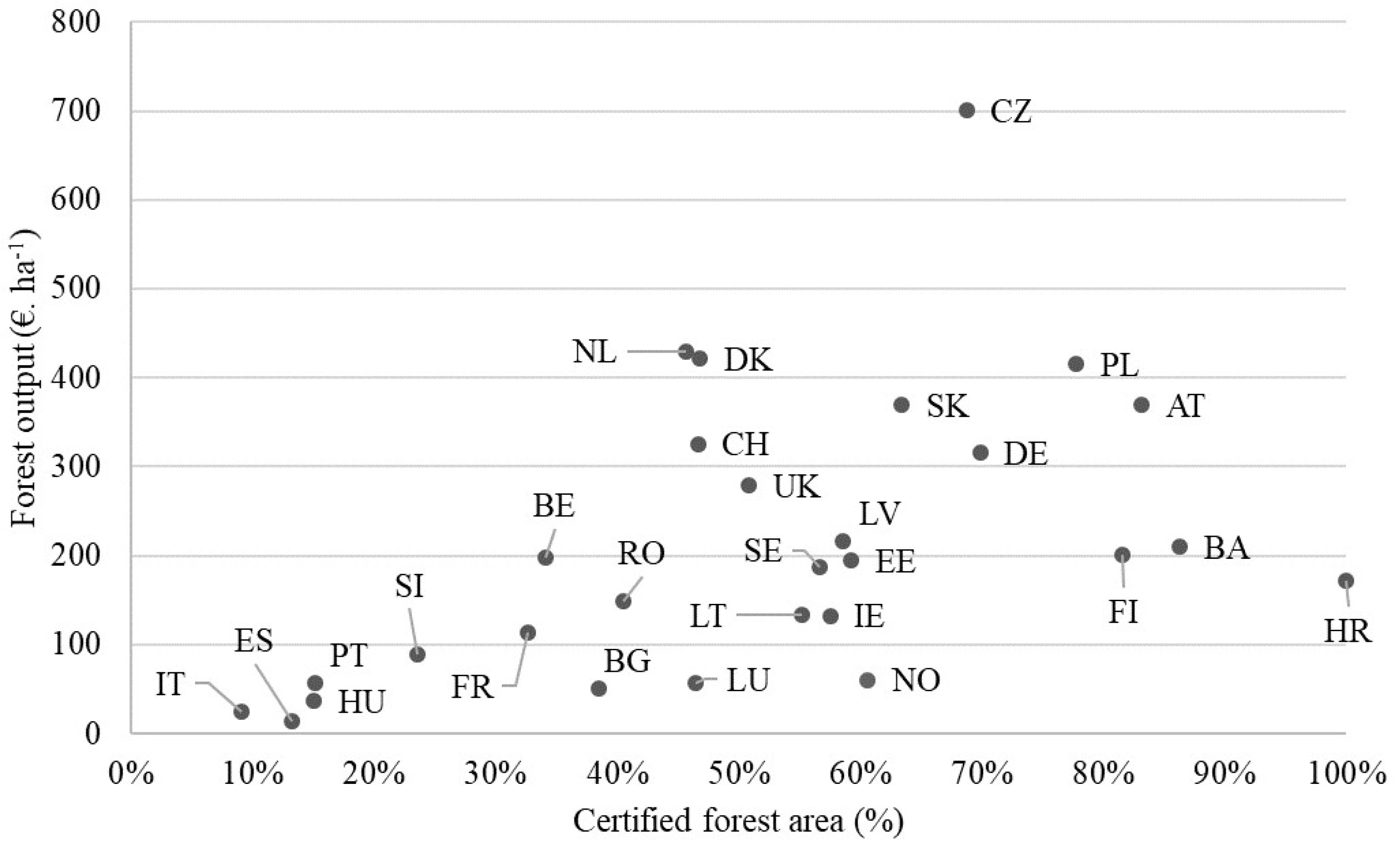

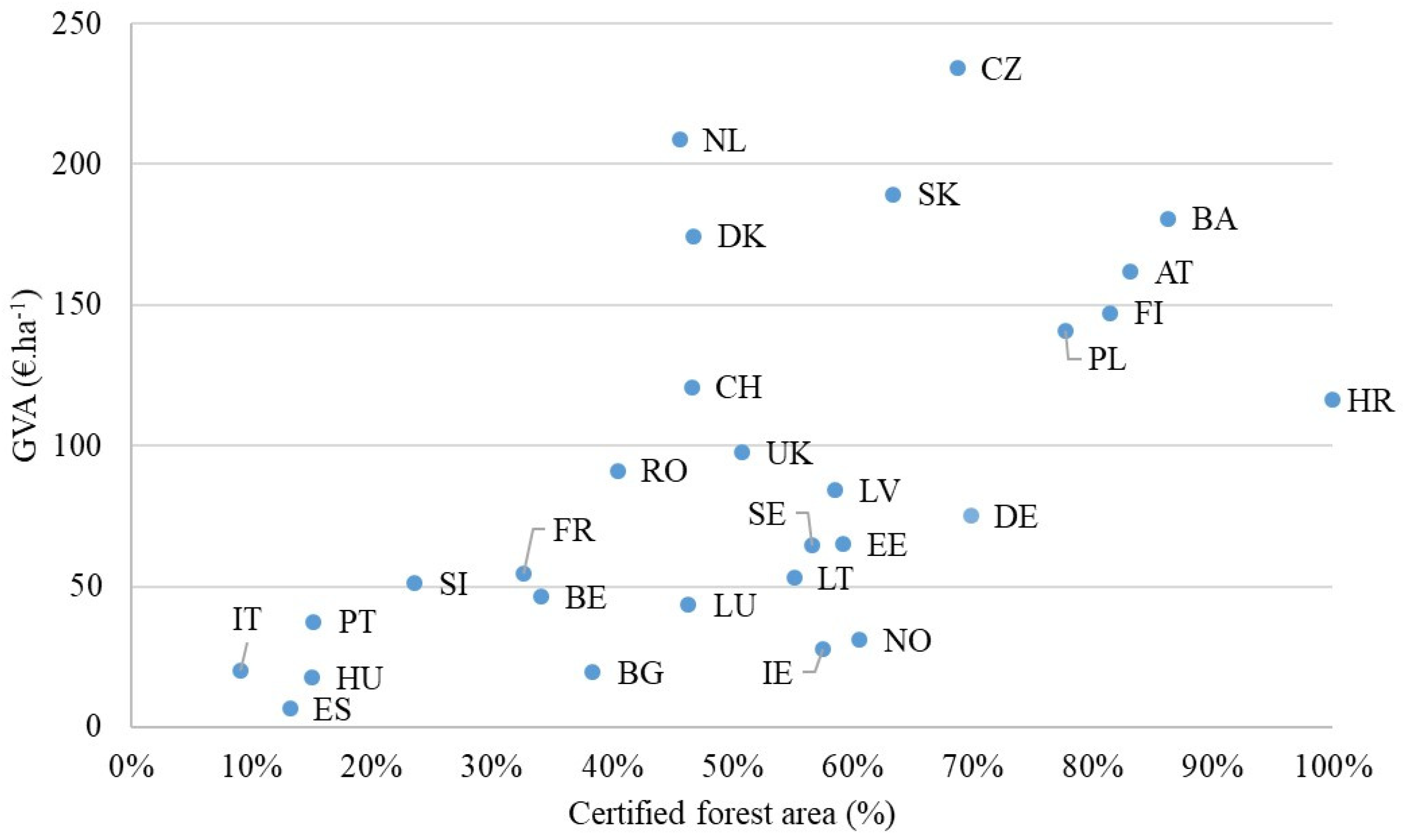

From a more economic perspective, Czechia stood out as the country with a higher expense for certified forest area, but also with larger outputs from forest sector and connected secondary activities. These results may be justified by the implementation of national policies that continued favoring conventional management techniques, with focus mostly on the production of timber and other wood products [

46]. The levels of those variables were noticeably lower in Italy and Spain. According to Martinho and Ferreira [

47], the production from forest-related activities (2012–2017) was higher in Germany, Czechia, Slovakia, Austria, and Slovenia when weighted by the total land area of the respective country. Considering total revenues for the same period, France, Germany, and Sweden proved to have the capacity to economically explore successfully their forest land [

48]. Both studies supported the importance of forests in Czechia, but weighting the economic indicators by the ratio of certified forest area it was possible to better understand the dynamic between forest certification and the economy of the sector in that country. As expected, results from the current study indicated that in terms of GVA, Czechia continued to be the top-ranked nation, followed by Netherlands and Slovakia. Croatia, a country with all its forest land certified by FSC, had a mean GVA value (116€. ha

−1), suggesting some inefficiency to successfully and fully explore and increase the outcomes of its forested territory. Such economic pattern may be the effect of (lack of) internal policies and the predominance of the public ownership of the forest territory [

43] with less active commercial focus.

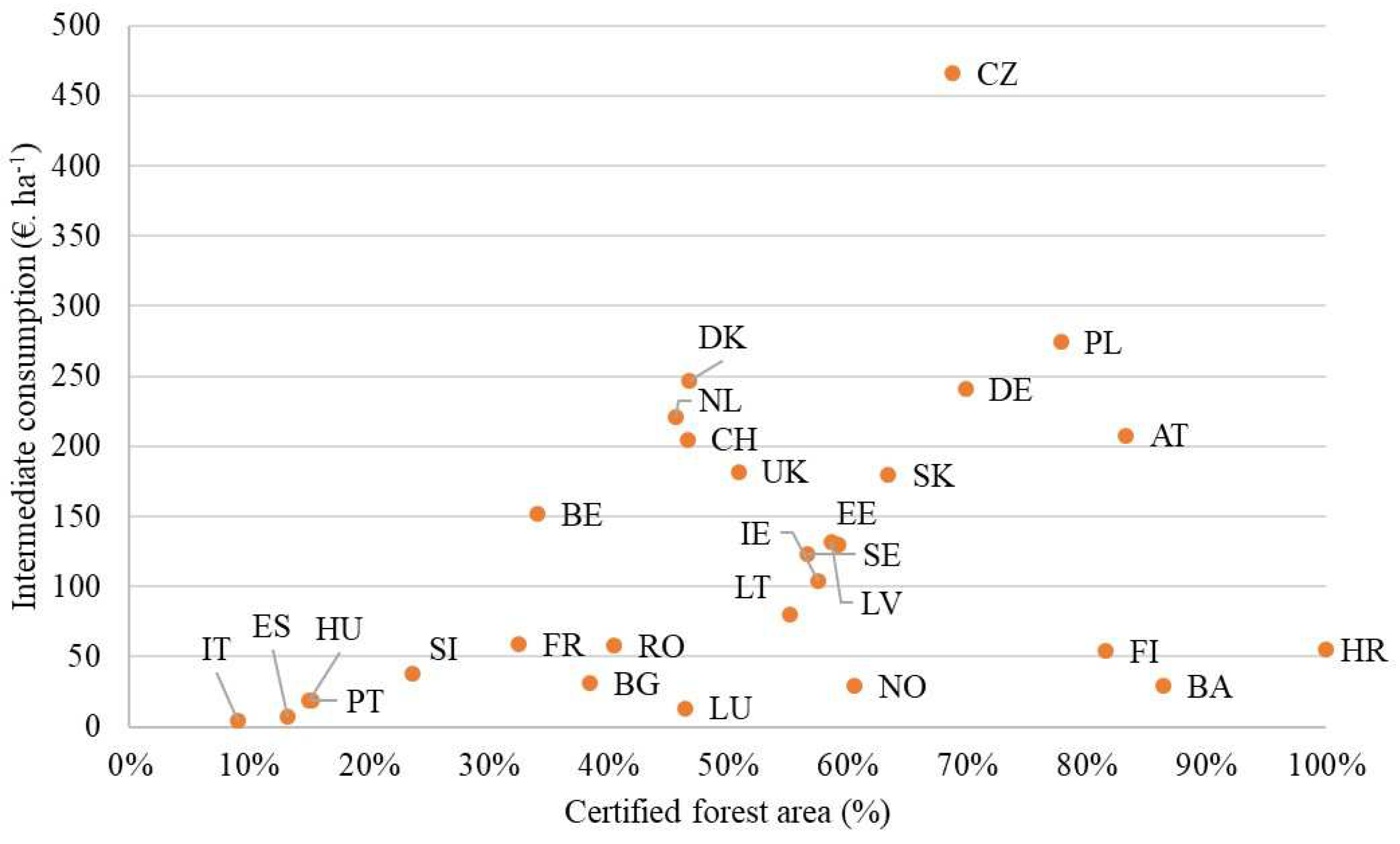

The overall analysis of the intermediate consumption demonstrated a tendency for costs to rise along with the increment of certified forest area, supporting the fact that the certification process is often expensive, particularly at a small scale [

6,

49]. However, this rise tends to plateau after a certain scale is reached within certification coverage (e.g., around 70% area certified) probably implying that it is indeed possible to sustain at scale a profitable certification scheme where costs are controlled and outputs may be further increased. Additionally, a rise in investment and the formation of green jobs has also been observed in nations with variable levels of forest cover, from those with little to those with a large and established portion of their territory covered by forest [

48]. The forest output pattern evidenced a positive bias, increasing with the ratio of forest with certification, but quite divergent among countries with more than 50% of the area certified. This is most probably due to external conditions specific for each country, such as market access and political and industrial adequate frameworks. In terms of the relation of GVA with the forest certified, it was nearly exponential, indicating that in general the more certified forest area, the higher the relevance of the sector in the economy of the country, which supports the value of such schemes. Our results reinforce the assumptions of other authors [

6,

39,

50], that the forest certification ought to support an economically, socially, and environmentally viable forest management. In Finland and Sweden, forest and forest management have become further economically relevant as a result of the high number of jobs associated with the forest industry and the rising demand for certified and sustainably managed forest derived products from significant international markets for timber and pulpwood [

39,

50].

National governmental authorities and their forest regulations have a significant impact on the economy of the forest sector, but the market context and access in the different European countries is also of crucial importance [

6,

44]. Particularly, markets for timber and pulpwood encouraged landowners to make expenditures in forest management to increase forest productivity [

50]. In the last years, forest certification helped to promote the shift of forest management from timber and productivity to a wider range of other ecosystem services such soil conservation and water regulation, using novel approaches to forest governance that involve the interaction of public and private stakeholders [

51,

52], targeting goals completely aligned with those established within the EPI and the SDG [

30,

31,

35,

36]

.

The findings from our work show no relation between the EPI (general) and the ratio of certified forest, with all of the investigated countries presenting a score equal or higher to 50. The only exception was Bosnia and Herzegovina who scored 39. These results are aligned to what was expected from a more general indicator as the EPI, where the contribution of forest sector is in some way diluted within the overall contributions of other sectors impacting the environment. The EPI ranks 180 nations worldwide on their progress towards enhancing environmental sustainability using 40 performance indicators within 11 categories [

30]. Results from the EPI-TBG indicator, connected to global protection of terrestrial ecosystems in biodiversity and habitat [

30], reinforced the absence of link with the ratio forest certification of the European countries already observed with the general EPI. Countries like Italy and Spain with circa 10% of certified forest area scored the same value as countries like Lithuania with 60% of forest with certification and Croatia with all its forest certified. Once more, Bosnia and Herzegovina recorded the lowest value, being the second country with more ratio of certified area. Not all the terrestrial ecosystems are forest related, varying greatly in type, number and dimension across countries. Also, the extent of countries investigated from all the continents, attenuates the differences among European countries. In general, European forest ecosystems are productive, well-connected to other forests, and successfully incorporated into the landscape [

3]. Having a rate of certified forest of nearly 50% across all EU just emphasizes these conclusions.

Higher variation was observed between the selected countries when considering the SDG 15 indicator, target 15.2.1, proportion of forest area within legally established protected areas. This indicator focuses specifically on protected forest areas, which have different status and focus than certified forest areas. With the exception of Italy and Spain, where the percentage of protected forest vastly exceeded the percentage of forest with certification, the trend among the nations with less than half of certified forest was for protected areas to follow along with the growth of certified forest area. No trend was seen over that threshold of certified area. The area of planted forest is growing in Europe, along with the demand for wood and other services provided by forest plantations [

53]. Forest plantations are often related to the conservation and recovery of natural forests [

54], however the majority of forest plantations are still mainly managed for wood production and tend to have low ratios of protected areas [

55]. The target addressing the proportion of forest area under a long-term management plan showed that Croatia, Finland, Czechia, Slovakia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Hungary had all their forest area covered by such planning, regardless the percentage of their forest area with certification. Except for Italy, Luxembourg and, Bosnia and Herzegovina (no data available), only Austria and Norway had ratios of forest area under a long-term management plan inferior to the certified forest. These findings suggest that, although forest certification can be a main driver in both sustainable commercial exploitation of forest areas, as well as, developing long-lasting management plans, in general European countries have a main concern to define and implement sustainable management forest strategies beyond forest certification, covering specific protected forest areas. The sustainable management of forest plantations, both at stand and landscape levels, is the most effective way to maintain the economic benefits of forest plantations while promoting their multifunctionality and the synergy between ecosystem services [

53,

54]. The attainment of sustainability in the forest sector in Europe might differ significantly between nations, not only through forest certification but also by the definition and adoption of case-specific measures and transparent national policies while playing the correct balance between certification and protection forest areas, to sustain a responsible balance for future generations. Depending on the country, it may have a negative effect on the economy cost structure, increasing costs and lowering GVA [

23], but can also led to currently unvalued and not yet monetized ecosystem services and recovery of valuable biomass.

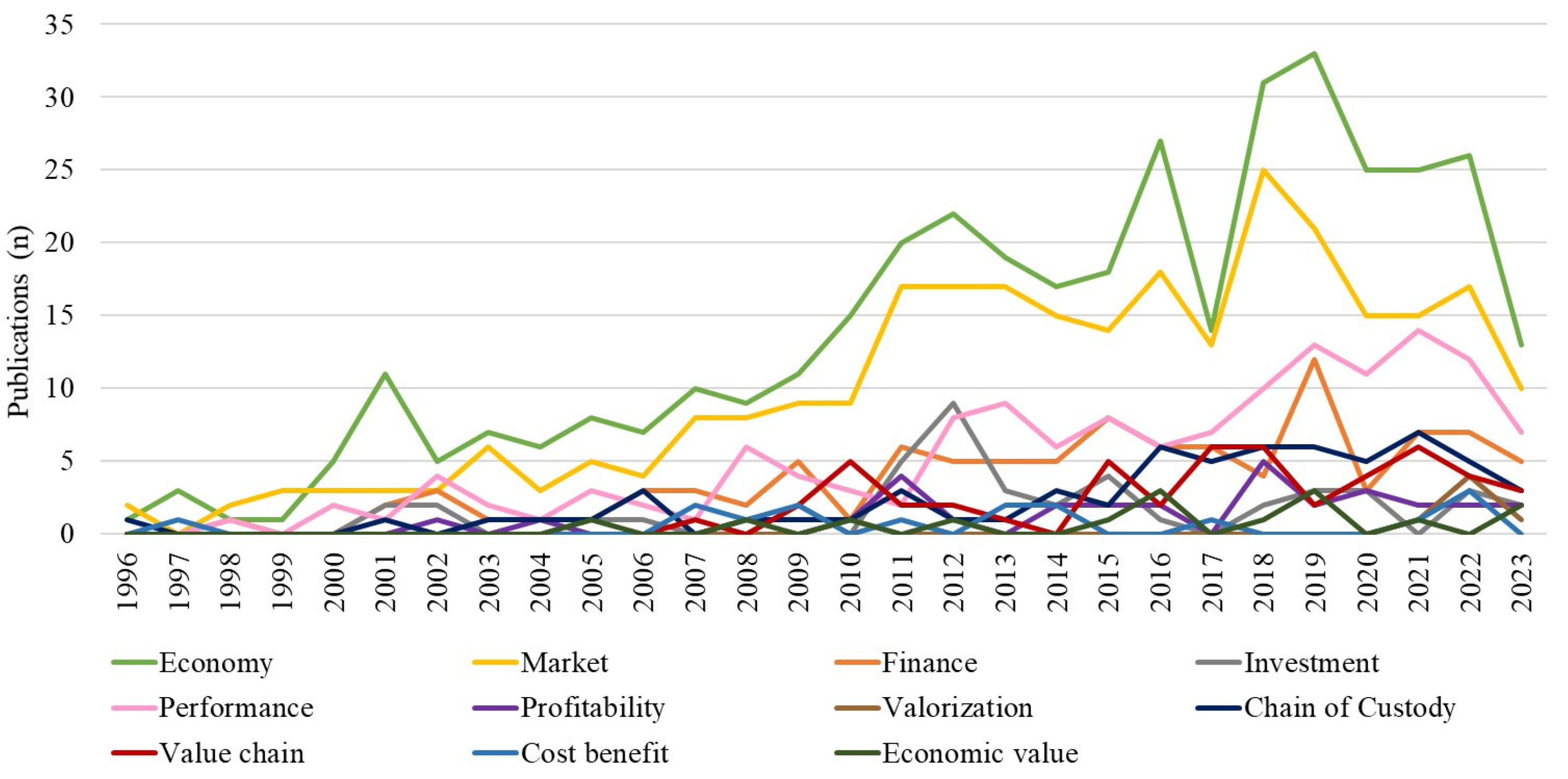

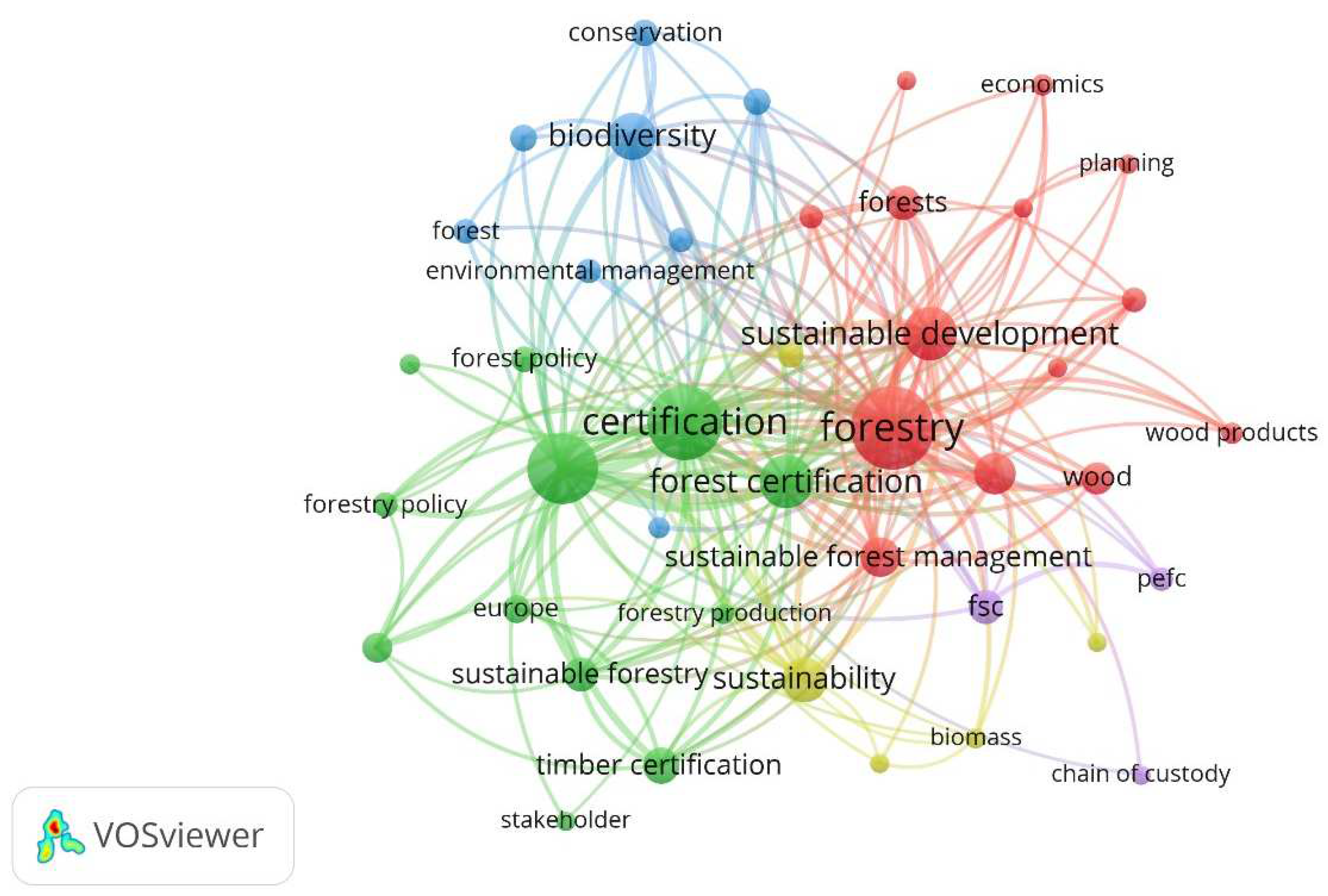

Scientific publications can also be useful tools in promoting informed discussions and guiding policymakers and investors towards sustainable forest management practices [

30,

56]. Results from a scientific search on the Scopus database showed that, despite the fact that only about 22% of the publications had co-authors from Europe, researchers in European countries are interested in researching the economic impacts of forest certification. In trying to establish the awareness and focus level of scientists in Europe to the interrelation between sustainable forest management and economic and market valorization of the forest certification schemes we performed a systematic search for specific key terms across the available literature, From the search terms screened, economy and market were the most represented words in the scientific publications from Europe related to forest certification and retrieved from Scopus database. These terms, together with the word performance, did not necessarily imply that the study would discuss any economic analysis, even though 74% of the papers contained more than one of the search terms. These findings are in line with Malek and Abdul Rahim [

52], that stated that, despite the numerous publications addressing forest certification publications, only a small number of papers have examined current patterns and trends on this topic. The first study on this matter was first published by 1996, three years after the FSC was established and the first forest areas were certified [

25]. Words as

chain of custody,

investment and

profitability started to be include in scientific papers only at the beginning of the 2000. Around 2006, concepts like

value chain and

cost benefit also begun to appear in academic journals. Despite the great level of specificity of the chosen search terms, no evident relationship between them and the keywords in the scientific articles was identified. Keywords were mostly centered on sustainable forest management and certification. Only one comparable keyword emerged,

economics, in one of the clusters interacting with forest management, planning, and productivity.

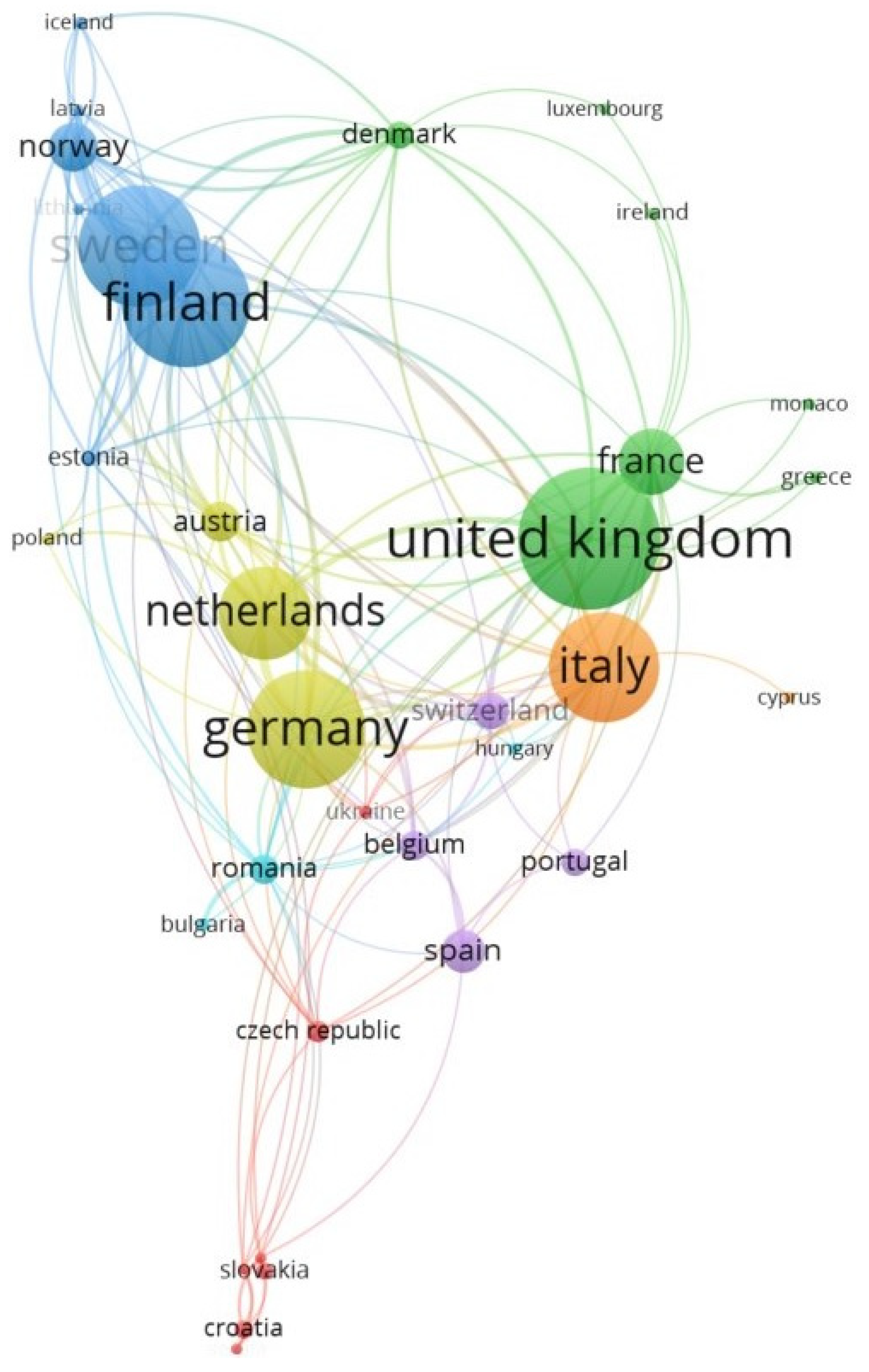

In relation to European countries, Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom, Germany, Netherlands and Italy stood out as the nations most represented in the scientific publications. It was difficult to define a clear link between the volume of scientific publications and the economic outputs of certified forests, but a positive trend emerged. Countries, such as Germany and Netherlands, with significant levels of investment when weighted by the ratio of certified forest of the respective country, exhibited a good commitment to research on this matter, contributing to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable forest management and informed investment decisions. A similar pattern was seen in countries like Finland with higher GVA associated to the forest sector. On the other hand, Italy with a lower ratio of certified forest, continued to contribute to the advance of scientific knowledge on forest certification matters. The outputs from that contribution were clearly noticeable considering the ranking of Italy in SGD 15.2.1 targets and EPI indicators. However, this does not yet translate to the economic value Italy is retrieving from such good knowledge and practices and certainly more incentives and an adequate political framework could boost the sector in countries like Italy. Results suggest that research in sustainable forest management is frequently acknowledged by countries that had evidence of investing in forestry, even if in some cases apart from the certification process. As a result, these nations normally devote substantial sums of money to universities, research centers, and network collaborations devoted to forestry research. Countries in Eastern Europe, particular Czechia and Croatia, the first with the highest GVA observed and, the second with the totality of its forest area certify but with a low GVA, had a less evident participation on scientific studies. Can a major focus on the timber market and the fact that the majority of the forest is managed by the state [

43], be contributing to these results? Many factors beyond scientific publications, such as financial resources, policies, and stakeholder engagement, influence investment and adequate exploitation in forestry. Overall, findings from the current study suggest that certification can help to enhance the financial performance of forest investments, mitigating the risks and improving the trust of investors and allowing the access of forest industries to international and highly competitive markets. On the other hand, our data also points out that there is still some competition between protection and certification of forest areas and that both mechanisms need to jointly work to foster a more sustainable future for forest land in EU. Finally, research and development in forest certification and related sciences, in concrete in the interface between natural and social forest sciences, can be further boosted in Europe, when compared to other world regions alongside suitable political incentives to leverage the informed and sustained forest we all aim to have in European land.