1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, accounting for 16% of all female cancers and this percentage is increasing [

1]. Specifically, between 2012 and 2019, the number of cases in Spain increased by 7.5% [

2]. The risk factors in developed and developing countries that increase the incidence of this disease are diet, decrease in the number of births, late first pregnancies, and reduction in the breastfeeding period [

1].

There are different types of mastectomy depending on the technique used in the operating theatre and the amount of tissue removed; in simple mastectomy, the entire breast is removed, including the skin and nipple-areola complex (NAC), and sometimes even some axillary lymph nodes [

3]. After mastectomy, it is possible to reconstruct the NAC, which is the last stage of the breast restoration process and can be performed by surgical intervention with grafts or dermopigmentation, also known as micropigmentation. The performance of these techniques with good results will lead to an improvement in self-concept, which will translate into an increase in self-esteem and a positive change in the woman's view of her body image [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Nipple tattooing is derived from the word "tatau" (to mark something), and since the 1970s, it has been used in the medical field to recreate parts of the body. The latter is a reliable and relatively simple technique that is performed on an outpatient basis [

6]. It is a safe technique with few complications, most of which can be avoided if good aseptic measures are used [

7].

It is important to understand the difference between the two techniques, tattooing and micropigmentation. The purpose of both is to decorate the human body through the implantation of pigments and dyes in the skin by means of needle puncture with needles of different thicknesses depending on the desired finish. However, tattooing is permanent in nature, and micropigmentation only has a temporary duration of several months or years because its implantation is at the level of the outermost layer of the skin [

8]. In tattoos, the pigments are deposited in the dermis, which is the intermediate layer of the skin, and is 4 mm thick, which means that the pigment is permanently fixed without the need for any kind of revision. However, in micropigmentation, they are deposited in the epidermis, the most superficial layer of the skin, which is only 1 mm thick and is composed of cells that are constantly renewed in a process that lasts approximately two months. This means that the pigment does not adhere completely but is erased, so it will be necessary to go over to achieve the fixation of the pigment [

8,

9].

With regard to legislation, this technique varies depending on the geographical area. At the European level, ResAP (2008) Resolution on safety requirements and criteria for tattooing and permanent makeup [

10] (which replaces the ResAP (2003) Resolution on tattooing and permanent makeup [

11]) is in force, specifying the legal requirements to be met by products for permanent makeup and tattooing, which will be included in a list of safe substances. The products used must be sterile, single-use, and correctly labelled, as indicated in the document, and disinfection and sterilization must be carried out by tattooists in accordance with national public health standards. Those receiving such treatment must be properly informed in advance of the possible risks involved [

10].

In Spain, breast areola micropigmentation is not financed by social security in all autonomous communities. Only a few countries, including Andalusia, benefit from its implementation in public hospitals [

12]. At the national level, the Spanish Micropigmentation Association (AEM) was founded in 1997 with the idea of adequately training professionals who will apply the technique, as well as establishing the necessary safety and hygiene measures to achieve a good result [

12,

13]. It has been clearly considered part of breast reconstruction, with the idea that this technique should be carried out in the same way throughout Spain. However, although Spanish health legislation introduced changes in 2019, it was unclear whether reconstruction was included in the health system [

14].

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer leads to a decrease in the quality of life because both the physical health and mood of the woman are affected, which can lead to a deterioration of her psychological state [

16]: negative self-evaluations, loss of self-confidence, and feelings of loss of physical and sexual attractiveness due to bodily changes resulting from the treatment necessary to deal with this disease. Among them, the loss of the affected breast is associated with a loss of femininity, since the breast represents a very relevant part of sexuality and personal identity [

2,

4].

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on the technique of micropigmentation of the nip-ple-areola complex at the San Cecilio University Hospital in Granada, including both quantitative and qualitative variables, the frequencies of which were calculated. The quantitative variables collected in this study were age and date of last surgery.

The study population consisted of women who, after undergoing a mastectomy, either unilaterally or bilaterally, visited the micropigmentation clinic to complete the breast reconstruction process in the nursing clinic. The inclusion criteria were women of any age who had already suffered from breast cancer and had the opportunity to complete the breast reconstruction process with the technique of micropigmentation of the nipple-areola complex in the specialist nurses' practice at the San Cecilio University Hospital in Granada, from its opening in December 2018 to December 2019 [

17,

18]. This study included women recruited in different ways, such as by referral from other healthcare professionals, news in the media, or recommendations from people close to the patients. All were included in the surgical demand list by the nurse who afterwards contacted them by telephone. The exclusion criteria were women who declared their disagreement with the technique, either due to fear of the procedure or due to therapeutic exhaustion, were excluded. Patients with whom it was impossible to contact were not taken into account, but rather all the patients who came for consultation during the period described above, which were 167 women.

3. Results

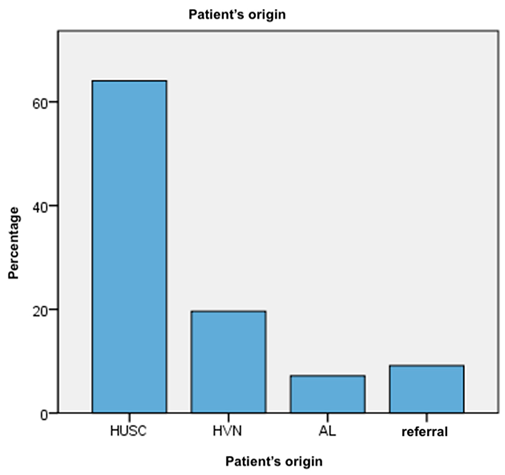

The sample consisted of 167 patients, of whom 24 declined treatment, 3 had second thoughts and cancelled the appointment, and 135 were accepted. Of those who decided to undergo treatment, 86 had undergone surgery before or during this study and 49 were waiting for their first appointment date to arrive or had previously completed breast reconstruction surgery. The patients had a mean age of 53.53 years, with a standard deviation of 8.208, and were in the age range of 35–75 years. Of the 167 women in the sample, 64.1% (98 women) came from the San Cecilio University Hospital in Granada, 19.6% (30 women) from the Virgen de las Nieves Hospital in Granada, 7.2% (11 women) from the province of Almería, and the remaining 9.2% (14 women) were referred by other means, either by other professionals, radio programs, or by recommendations of people close to the patients (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient’s origin.

Table 1.

Patient’s origin.

These women underwent surgery between 2002 and 2019, with a higher frequency in the latter two years. 36 of them (23.8%) underwent surgery in 2018 and 19 women (12.6%) in 2019 (

Table 2).

Of the total sample, there are 9 women for whom it is not known whether the mastectomy they underwent was unilateral or bilateral. Of the remaining 158 women, 82.9% underwent unilateral versus 17.1% bilateral mastectomy. Of the total sample, 14.9% decided to refuse the micropigmentation technique, of which 50% were aged 56 years or older. From most to least frequent, the reasons for such refusal were not having a reconstructed breast (all were patients over 60 years of age), having a poor aesthetic result, many scars, not having skin, and even indicating that they had great aesthetic sequelae (in an age range of 51–65 years), due to exhaustion and/or the presence of numerous surgical interventions (regardless of age). One of them justified her refusal because she was in a wheelchair and thought that she was too old (61 years old). It should be noted that two women who refused the procedure claimed that they did not need it or did not have a complex (48 and 56 years old). However, one patient denied the process and claimed not to look at her breast (59 years). Women younger than 58 years old had dermatological and vascular problems as a reason for refusal, and only one refused due to poor cancer progression, requiring palliative care, and subsequently died at the age of 55 years.

Of the total number of women who accepted, only 51.5% underwent the technique during the period between the opening of this nursing practice and the date of data collection for this study; the remaining women did not undergo the treatment for various reasons, including pending breast reconstruction surgery such as prosthesis replacement or plastic and reconstructive surgery, not having been scheduled yet, or not having reached the date of their first appointment at the practice during that period. It became clear that women under 48 years of age did not refuse to undergo this technique. The most frequent reasons for refusal were the absence of breast reconstruction (16.7%), exhaustion of the patients after numerous surgical interventions (16.7%), and the patients' consideration that they had a poor aesthetic result or numerous scars (16.7%).

Most women who refused to undergo this technique underwent unilateral mastectomy (82.6 %). According to the data collected, reconstruction with prostheses was not a determining factor to justify whether this was really an influential reason in the decision to accept or reject the technique, since a similar number of refusals were recorded in patients reconstructed with prostheses or by another method (9 vs. 11, respectively). In terms of complications arising from the application of this treatment recorded up to the date of clinical data collection, there were two complications, both of which were minor. One of them was a torpid evolution that required several cures in the consultation room and the delay of the appointment for review, that is, the patient was scheduled two months after the first visit and not the following month as it should have been, which was a consequence of the early crusting and was cured with a hydrocolloid patch on the treated area. The other complication was the appearance of itching and redness of the PDA eight days after the second consultation appointment; therefore, at the next visit, two months later for the follow-up, treatment with Linitul was performed.

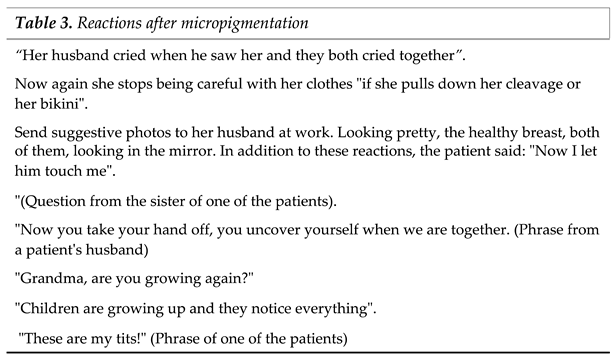

A series of phrases and reactions that the patients commented on to the nurse who performed the micropigmentation after the technique was completed were collected (Table 3). All of them suggested that the treatment was effective and could produce an improvement in self-concept by reducing negative self-evaluations and the feeling of loss of physical and sexual attractiveness.

4. Discussion

The average age of the micropigmented women in this study was 53.53 years, similar to other studies, in which the average age ranged between 52 and 56 years [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The minimum age of patients with dermopigmentation on NAC, both in this study and in others [

6,

21,

22], was 34 years or more. However, the study by Gogh et al. had a minimum age of 30 years [

20].

This study included both patients who accepted and those who refused to undergo the NAC dermopigmentation procedure as part of the breast reconstruction process, as opposed to the articles found [

6,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] that simply showed data from women who accepted the procedure. Despite this, if we only counted the patients who accepted the technique in our study, the sample size was larger than that of other studies, which had a rather small sample size [

6,

21,

22,

23,

25]. In this study, we counted patients with unilateral and bilateral micropigmentation, whereas in the articles we found [

6,

21,

22,

23,

24], this distinction was not reflected.

NAC micropigmentation is not a new technique, as studies of this technique have been conducted for more than 20 years [

24]. It is considered a safe technique, as long as correct aseptic measures are followed [

8,

9]. This fact is reinforced when observing the results derived from the application of this technique in our study as well as in other articles that studied the same procedure in mastectomized women, regardless of the age of the articles. In the present study, 2 mild complications were recorded, representing 1.48% of the total sample, which resulted in a lower percentage of complications compared to the study by Goh et al., with a sample similar to ours (110 patients), in which 7.27% (8 patients) suffered bandage-related complications or local erythema, while 81% (89 patients) did not undergo any reaction. Even when compared with older studies, from 1995, and having advanced the technique, similar results appear, with a sample of 151 patients; 3% suffered superficial infection and 0.66% suffered skin rashes or desquamation.

This study obtains similar results to other relevant studies carried out in patients with similar ages and using the same procedure, so it can be concluded that the NAC micropigmentation technique is a simple and safe technique, with few complications, being satisfactorily valued by the patients as the expected result can be visualised using photomontage techniques, with nursing professionals trained in micropigmentation being the ideal ones to carry it out [

21,

22,

23,

25,

26]. It is important to mention that most of the studies on NAC reconstruction are carried out through surgical techniques and there are scarce studies on alternative techniques such as micropigmentation or on other techniques that can be performed on women who reject the surgical technique [

27,

28].

It is suggested for the future, to provide patients with a consultation survey with the intention of obtaining data that will serve as a record to study more objectively if the application of micropigmentation in the nipple-areola complex improves the quality of life of the patient, and if it is capable of generating positive changes in the psychological health of the woman as a consequence of an increase in self-esteem due to the change towards a more positive vision of her body image, and in this way also to check whether or not this treatment could really produce an improvement in sexual relations by recovering the feeling of personal satisfaction with her physique [

19,

29,

30,

31].

5. Conclusions

It is a technique that is little known, both by health workers and by women undergoing mastectomy.

Although it is observed that a large percentage of women who have been offered this technique accept it, the highest proportion are those under 48 years of age. It is a technique that offers minimum adverse effects; therefore, it would be interesting to study how the application of the technique affects women's self-esteem and quality of life.

This study only included women who underwent mastectomy as a result of breast cancer, so the results cannot be extrapolated to the rest of the population. In fact, the nursing practice where this technique is performed has recently been created, so that prospective studies can be carried out in which both the level of satisfaction and questions associated with the technique itself are considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision and methodology, Tovar-Gálvez, M.I.; Cortés-Martín, J.; Rodríguez-Blanque, R.; methodology, Sánchez-García, J.C.; software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, Cortés-Martín, J.; Gómez-Muñoz, L. and Pinedo-Extremera, M.S.; sources, Pinedo-Extremera, M.S.; Cortés-Martín, J.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation —review and editing, visualization, Rodríguez-Blanque, R.; Tovar-Gálvez, M.I. and Sánchez-García, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the data is restricted in accordance with Spanish law and will be shared upon express request by identification and purpose of use by email to the correspondence author Juan Carlos Sánchez-García (

jsangar@ugr.es).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical consideration

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethics standards of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Granada Provincial Research Ethics Committee, part of the Network of Ethics Committees of the Andalusian Public Health System, whose approval is available on request to the corresponding author.

References

- WHO - Breast cancer: prevention and control [Internet]. WHO. [cited 22 Nov. 2023]. Available online: https://www.who.int/topics/cancer/breastcancer/es/index1.html.

- All about cancer [Internet]. [cited 25 April 2020]. Available online: https://www.aecc.es/es/todo-sobre-cancer.

- Martin BR. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment in patients diagnosed with breast cancer [Internet]. University of Salamanca; 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 3]. p. 1. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=256715.

- Mastectomy [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 6]. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/es/cancer/cancer-de-seno/tratamiento/cirugia-del-cancer-de-seno/mastectomia.html.

- Sebastián J, Manos D, Bueno M J, Mateos N. Body image and self-esteem in women with breast cancer participating in a psychosocial intervention programme. Clínica Salud; 2007;18(2):137-61. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4728093.

- Potter S, Barker J, Willoughby L, Perrott E, Cawthorn SJ, Sahu AK. Patient satisfaction and time-saving implications of a nurse-led nipple and areola reconstitution service following breast reconstruction. Breast. June 1, 2007;16(3):293-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17241786/. [CrossRef]

- Jabor M, Shayani P, Collins D, Karas T, Cohen B. Nipple-Areola Reconstruction: Satisfaction and Clinical Determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. August 2002;110(2):457-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12142660/. [CrossRef]

- Bayón. JC, Reviriego E, Gutiérrez A, Galnares-Cordero L. Evaluation of the scientific evidence on micropigmentation of the nipple-areola complex, requirements for its adequate performance and costs [Internet]. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality; 2018 p. 170. (Health Technology Assessment Reports: OSTEBA.). Available online: http://www.euskadi.eus/web01-a2aznscp/es/k75aWebPublicacionesWar/k75aObtenerPublicacionDigitalServlet?R01HNoPortal=true&N_LIBR=052131&N_EDIC=0001&C_IDIOM=es&FORMATO=.pdf.

- Uhlmann NR, Martins MM, Piato S. 3D areola dermopigmentation (nipple-areola complex). Breast J. 2019;25(6):1214-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31321852/. [CrossRef]

- Rojas M, Solera D, Herrera C, Vega-Baudrit J. Cutaneous organ regeneration by virtue of tissue engineering. Momento. June 2020;(60):67-95. Available online: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/momento/article/view/82752.

- Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products SG of PS. Translation of the Resolution of the Council of Europe on tattoos and permanent make-up [Internet]. Spanish Micropigmentation Association. [cited 25 April 2023]. Available online: https://www.asociacionmicro.com/legislacion/legislacion-europea.

- Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products SG of PS. Council of Europe Resolution [Internet]. Presentation of the translation of the Council of Europe resolution on tattoos and permanent make-up. [cited 11 May 2023]. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/8560599/resolución-consejo-de-europa.

- Royal Decree 198/1996, of 9 February, which establishes the curriculum of the higher level training cycle corresponding to the title of Higher Technician in Aesthetics. [Internet]. BOE No. 63 Mar 13, 1996 p. 10021-8. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-1996-5841.

- Order of 28 October 2016, which updates the surgical procedures included in Annex I of Decree 209/2001, of 18 September, which establishes the guarantee of surgical response time in the Andalusian Public Health System and establishes the corresponding amounts. [Internet]. [cited 9 April 2023]. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2016/211/27.

- Decree 71/2017, of 13 June, regulating the hygienic-sanitary and technical conditions of the activities related to the application of tattooing, micropigmentation and piercing techniques. [Internet]. BOJA No. 116 Jun 20, 2017 p. 10-33. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2017/116/1.

- Order SCB/480/2019, of 26 April, amending Annexes I, III and VI of Royal Decree 1030/2006, of 15 September, which establishes the portfolio of common services of the National Health System and the procedure for updating it. Sec. 1 Apr 26, 2019 p. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2019/04/26/scb480/dof/spa/pdf.

- López MA, Hernández MD, Chantar L, Muñoz C. Micropigmentation. Brushstrokes of self-esteem after breast cancer. Micropigmentación. Pinceladas de autoestima tras el cáncer de mama. Revista de enfermería. 2015; 20(49):44-49. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5408068.

- The San Cecilio Hospital launches areolar micropigmentation in breast reconstruction after cancer surgery for the whole of Granada [Internet]. [cited 25 April 2023]. Available online: https://www.husc.es/noticias/el-hospital-san-cecilio-pone-en-marcha-para-toda-granada-la-micropigmentacion-areolar-en-la-reconstruccion-de-mama-tras-la-cirugia-oncologica.

- Tattoos of life after breast cancer at the PTS Clinic of Granada [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 13]. Available online: https://www.granadahoy.com/granada/Tatuajes-cancer-mama-Clinico-PTS-Granada_0_1434457205.html.

- Cha, H. G., Kwon, J. G., Kim, E. K., & Lee, H. J. Tattoo-only nipple-areola complex reconstruction: Another option for plastic surgeons. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2020, 73(4), 696-702. [CrossRef]

- Goh SCJ, Martin NA, Pandya AN, Cutress RI. Patient satisfaction following nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and tattooing. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. Mar 1, 2011;64(3):360-3. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20570584/. [CrossRef]

- Murphy AD, Conroy FJ, Potter SM, Solan J, Kelly JL, Regan PJ. Patient satisfaction following nipple-areola complex reconstruction and dermal tattooing as an adjunct to autogenous breast reconstruction. Eur J Plast Surg. Feb 1, 2010;33(1):29-33. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00238-009-0368-x. [CrossRef]

- Valdatta L, Montemurro P, Tamborini F, Fidanza C, Gottardi A, Scamoni S. Our experience of nipple reconstruction using the C-V flap technique: 1 year evaluation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. Oct 1, 2009;62(10):1293-8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18691957/. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa SG de P, Matos JRF, Dias IS, Pessoa BBG de P, Alencar JCG de. Simple and safe technique for areolopapillary reconstruction with intradermal tattooing. Rev Bras Cir Plástica. September 2012;27(3):415-20. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbcp/a/nJPkWk86bN9Tqtnc85tFFHx/?lang=en.

- Spear SL, Arias J. Long-Term Experience with Nipple-Areola Tattooing. Ann Plast Surg. September 1995;35(3):232-236. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7503514/. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson JHW, Tracey A, Eltigani E, Park A. The patient's experience of a nurse-lednipple tattoo service: a successful programme in Warwickshire. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. Oct 1, 2006;59(10):1058-62. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16996428/.

- Tan, .Y Y., et al. Patient-reported outcomes for nipple reconstruction: Review of literature. The Surgeon, 2021, vol. 19, no 5, p. e245-e255. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, A.; Lee, M. How to do a simple dermabrasion tattoo technique for a single-stage nipple areolar reconstruction. Australasian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 2023, vol. 6, no 2, p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. H.; Wee, S. Y. A new method for inverted nipple treatment with diamond-shaped dermal flaps and acellular dermal matrix: a preliminary study. Aesthetic plastic surgery, 2023, p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Sezer A. Nipple-Areola Reconstruction. In: Rezai M., Kocdor M.A., Canturk N.Z. (eds) Breast Cancer Essentials. 2021 Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, M. J., Streb, J., Mirucka, B., Słowik, A. J., & Jach, R. (2018). The relationship between surgical treatment (mastectomy vs. breast conserving treatment) and body acceptance, manifesting femininity and experiencing an intimate relation with a partner in breast cancer patients. Psychiatr. Pol. 2018; 52(5), 859-872. Available online: https://www.psychiatriapolska.pl/uploads/images/PP_5_2018/ENGver859Jablonski_PsychiatrPol2018v52i5.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Frost, Stephen, et al. "Patient perspectives on nipple-areola complex micropigmentation during the COVID-19 pandemic." Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 2022, Vol. 75, no 8, p. e2831-2870. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Women undergone surgery/year.

Table 2.

Women undergone surgery/year.

| |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| 2002 |

1 |

,7 |

| 2004 |

1 |

,7 |

| 2005 |

3 |

2,0 |

| 2006 |

2 |

1,3 |

| 2007 |

3 |

2,0 |

| 2009 |

5 |

3,3 |

| 2010 |

7 |

4,6 |

| 2011 |

7 |

4,6 |

| 2012 |

12 |

7,9 |

| 2013 |

13 |

8,6 |

| 2014 |

12 |

7,9 |

| 2015 |

12 |

7,9 |

| 2016 |

9 |

6,0 |

| 2017 |

9 |

6,0 |

| 2018 |

36 |

23,8 |

| 2019 |

19 |

12,6 |

| Total |

151 |

100,0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).