Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- I

- Water Resources Plans;

- II

- Water bodies classification according to their predominant uses;

- III

- Granting of water use rights;

- IV

- Charging for the use of water resources;

- V

- Compensation to municipalities;

- VI

- Water Resources Information System.

|

|---|

3. Materials and Methods

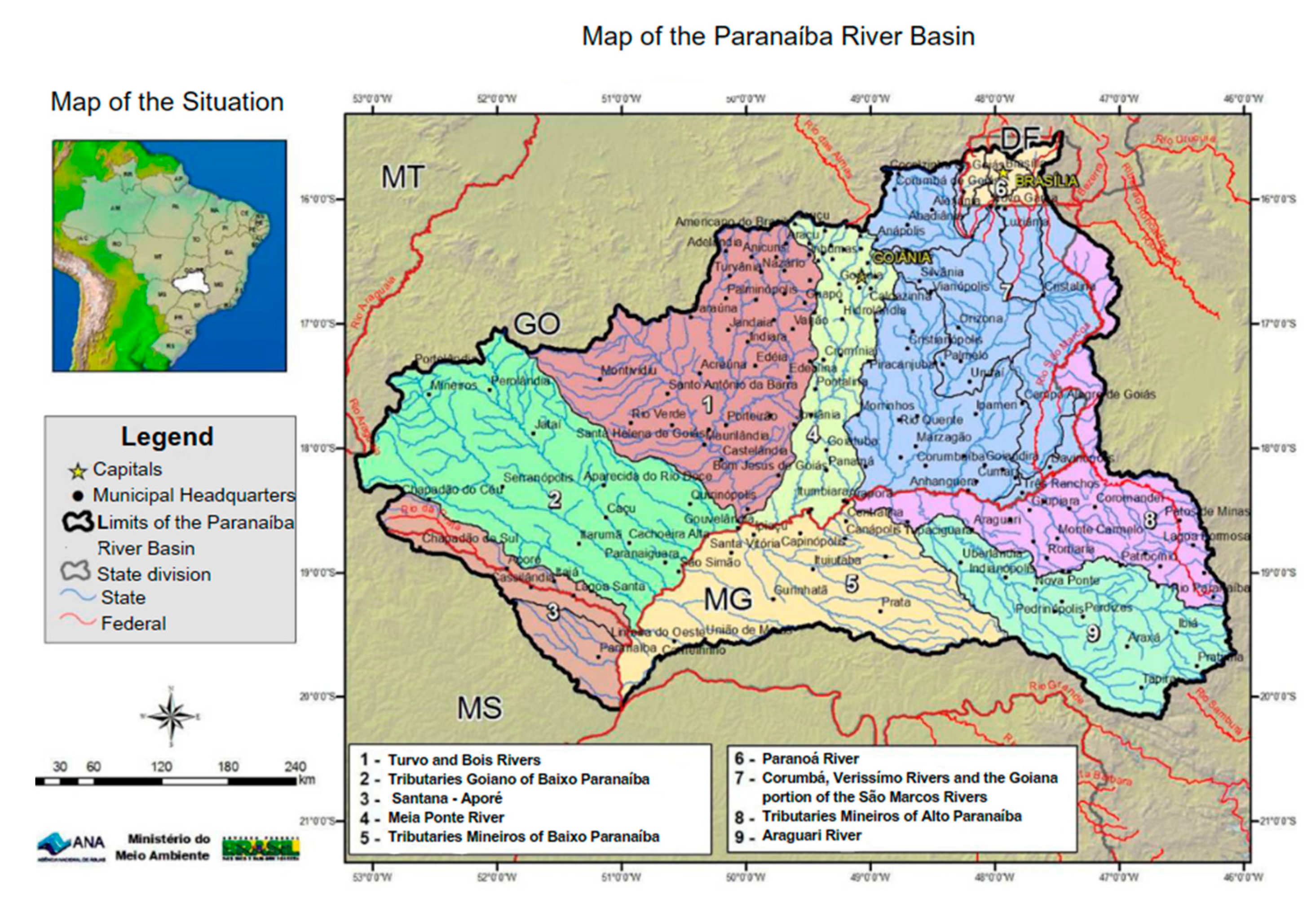

3.1. Study area characterization

3.2. First phase – CAPES journal articles

3.3. Second phase – federal water resource charge data for the Paranaíba River Basin.

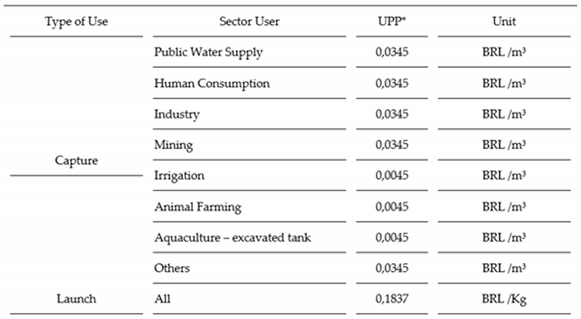

- (a)

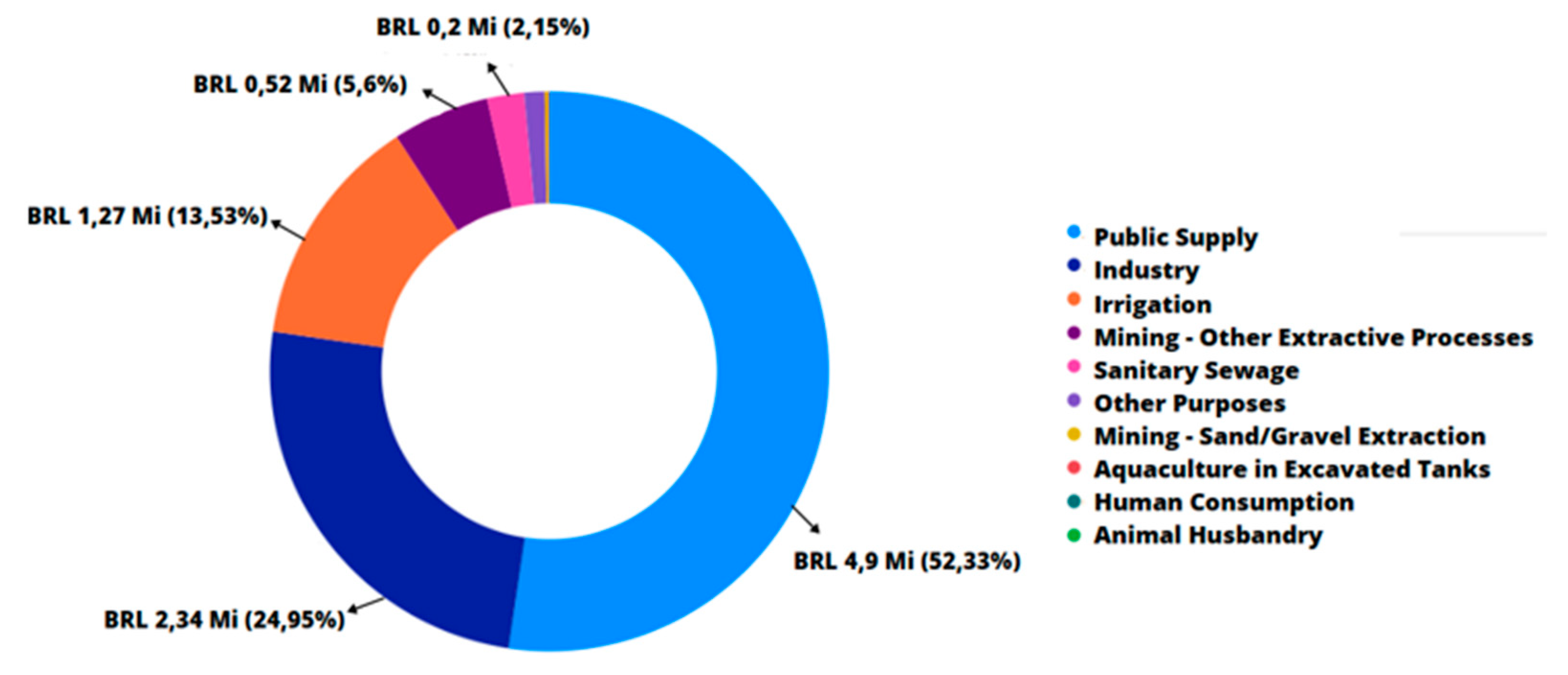

- Purpose of water resource use: Among the uses charged in the Paranaíba River Basin, they were classified as follows: Public Supply, Aquaculture in Excavated Tanks, Human Consumption, Animal Husbandry, Sanitary Sewage, Industry, Irrigation, Mining – Sand/Gravel Extraction, Mining – Other Extractive Processes, and finally, other purposes.

- (b)

- Users by Purpose (Unit): The total number of users per type of water resource use charged in the Paranaíba River Basin was quantified.

- (c)

- Withdrawal Flow (m³): The volumes withdrawn and charged for different purposes were measured.

- (d)

- Discharge Flow (m³): The volumes of discharge resulting from post-use of water resources were measured.

- (e)

- Amount Charged (BRL): The revenues obtained from the charge for water resources extracted from the Paranaíba River Basin were quantified by purpose of use and federal unit.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Bibliometric analysis

| Studies | Country | Main conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| (Alencar, K. et al., 2018) | Brazil | The implementation of water charges in the Rio Grande basin is feasible, indicating irrigation as the activity that most uses water in the basin. Furthermore, it is suggested not to establish a limit for the economic impact on the agricultural sector, or to establish it at a significant value to encourage rational water use. |

| (Alho da Costa, F., 2022) | Brazil | Charging for the use of water resources can be an important strategy to ensure the sustainable use of these resources in Brazil. The participation of society in the definition of charging policies and water resource management is of great importance to ensure equity and transparency in the process, requiring clear and effective legislation. |

| (Almeida, M. e Curi, W., 2016) | Brazil | It highlights that integrated water resource management involving the participation of different actors and joint actions is essential to ensure the availability of water for all uses and users. Finally, it is suggested that the implementation of public policies and incentive programs, such as tax reductions for companies that use sustainable practices, can help promote sustainable water resource management. |

| (Campos, J., 2013) | Brazil | Integrated water resource management is a relatively recent and complex challenge that requires the adoption of conservation measures and rational water use, as well as the promotion of public policies and actions that encourage society's participation in water resource management. |

| (Demajorovic, J. et al., 2015) | Brazil | Charging for water use can incentivize companies to adopt more sustainable and efficient water practices. The authors point out that charging can stimulate companies to invest in more efficient technologies, reduce waste, and promote water recirculation and reuse. However, water charging is not the sole solution for sustainable water resource management. |

| (Ferreira, A. F. A. e Oliveira-Filho, E. C., 2021) | Brazil | Farmers have a limited understanding of the importance of paying for water use and how this system can contribute to sustainable water resource management. While some farmers are willing to pay for water use, the majority do not recognize the need to financially contribute to water resource maintenance. |

| (Ióris, A., 2012) | Brazil | Water resource management in Brazil has a long history marked by progress and setbacks. Despite advances in water resource management in recent decades, significant challenges remain, such as lack of financial and human resources, water pollution, and water scarcity in arid and semi-arid regions |

| (Ladwig, N. et al., 2017) | Brazil | Charging for water use in irrigated rice production in the southern region of Santa Catarina can have a significant impact on production costs, especially for farmers with lower economic power. The study shows that costs vary according to river flow and users' capacity to pay for water, which can lead to inequalities in agricultural production and water distribution. |

| (Leite, G. e Vieira, W., 2010) | Brazil | Charging for water use can incentivize companies to adopt more sustainable and efficient water practices. The authors point out that charging can encourage companies to invest in more efficient technologies, reduce waste, and promote water recirculation and reuse. However, water charging is not the only solution for sustainable water resource management. |

| (Lima, L. et al., 2019) | Brazil | Farmers have a limited understanding of the importance of paying for water use and how this system can contribute to sustainable water resource management. While some farmers are willing to pay for water use, the majority do not recognize the need to contribute financially to the maintenance of water resources. |

| (Morais, J. et al., 2018) | Brazil | Water resource management in Brazil has a long history marked by progress and setbacks. Despite advancements in water resource management in recent decades, it still faces significant challenges such as lack of financial and human resources, water pollution, and water scarcity in arid and semi-arid regions. |

| (Odppes, R., et al., 2018) | Brazil | Charging for water use in irrigated rice production in the southern region of Santa Catarina can have a significant impact on production costs, especially for farmers with lower economic power. The study shows that costs vary according to river flow and users' payment capacity, which can lead to inequalities in agricultural production and water distribution. |

| (Santin, J. e Goellner, E., 2013) | Brazil | The use of the Shapley value can be an efficient methodology for charging for water use in river basins, especially in situations of high complexity and socioeconomic heterogeneity. |

| Oliveira, V. et al., 2020) | Brazil | Cost sharing is an effective tool for water resource management and can help incentivize the adoption of sustainable practices in the region. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of participation and cooperation among different stakeholders involved in watershed management. |

| (Resende Filho, M. et al., 2011) | Brazil | Charging for water use can lead to improved technical efficiency in water and input use in agricultural production. |

4.2. Federal water resource charging in the Rio Paranaíba

| Purpose | Users by Purpose (Un) | Capture Flow (m³) |

Discharge Flow (m³) |

Charged Value (BRL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Water Supply | 17 | 284.626.793,76 | 119.275.453,99 | 4.901.701,50 |

| Aquaculture in Excavated Tanks | 18 | 2.707.809,05 | 2.707.809,05 | 5.696,54 |

| Human Consumption | 13 | 114.548,87 | 114.548,87 | 2.428,3 |

| Animal Farming | 18 | 84.575,04 | 84.575,04 | 382,33 |

| Sanitation | 15 | 179.616.266,40 | 80.239.275,29 | 200.960,02 |

| Industry | 27 | 150.514.764,83 | 76.497.409,35 | 2.336.543,73 |

| Irrigation | 716 | 655.348.081,44 | 473.418.684,75 | 1.267.277,54 |

| Mining - Sand/Gravel Extraction | 11 | 866.012,00 | 866.012,00 | 15.706,45 |

| Mining - Other Extraction Processes | 7 | 24.766.923,28 | 24.640.923,28 | 382,33 |

| Others | 45 | 5.908.888,54 | 5.289.001,82 | 110.986,74 |

| Federation Units | Charged Value (BRL) |

|---|---|

| Distrito Federal | 4737768,55 |

| Goiás | 2430934,15 |

| Minas Gerais | 1943371,74 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 68464,44 |

| Outras | 185935,91 |

| Municipalities | Predominant purpose of water resource use |

|---|---|

| Brasília | Irrigation |

| Catalão | Irrigation |

| Araporã | Irrigation |

| Santa Vitória | Irrigation |

| Davinópolis | Mining - Other Extraction Processes |

| Itumbiara | Irrigation |

| Ouvidor | Mining - Other Extraction Processes |

| Chapadão do Céu | Irrigação |

| Goiânia | Sanitary Sewage |

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ióris, A. (2012). Passado e Presente dos Recursos Hídricos no Brasil. Finisterra, 41(82), 55-74. [CrossRef]

- Alho da Costa, F. A. (2022). Cobrança pelo Uso dos Recursos Hídricos como Estratégia para seu Uso Sustentável no Brasil. Revista de Direito e Sustentabilidade, 7(2), 113.

- Campos, J. N. B. (2013). A Gestão Integrada dos Recursos Hídricos: Uma Perspectiva Histórica. Revista Eletrônica de Gestão e Tecnologias Ambientais, 1(1), 111-121. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. (1997). Lei n. 9.433, 8 de Janeiro de 1997 Dispõe Sobre a Política Nacional dos Recursos Hídricos e Dá Outras Providências. Brasília. Governo Federal.

- Santin, J. R., & Goellner, E. (2013). A Gestão dos Recursos Hídricos e a Cobrança pelo seu Uso. Sequência (Florianópolis), 34(67), 199-221. [CrossRef]

- Morais, J. L. M., Fadul, E., & Cerqueira, L. (2018). Limites e Desafios na Gestão de Recursos Hídricos por Comitês de Bacias Hidrográficas: Um Estudo nos Estados do Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Eletrônica da Administração (Porto Alegre), 24(1), 238-264. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V., Brose, M., & Vaz, V. (2020). Rateio de Custos Como Alternativa de Proteção e Recuperação da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Pardo. Colóquio (Taquara.), 17(4), 279-298. [CrossRef]

- Comitê da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paranaíba. (2020). Deliberação n. 115/2020, Dispõe Sobre a Atualização dos Mecanismos e Valores de Cobrança pelo Uso dos Recursos Hídricos de Domínio da União na Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paranaíba e Dá Outras Providências. Itumbiara, CBHRP.

- Agência Reguladora de Águas, Energia e Saneamento Básico do Distrito Federal. (2023). Mapa da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Paranaíba. Brasília, Adasa.

- Donato, H., & Donato, M. (2019). Stages For Undertaking A Systematic Review. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 32(3), 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Galvão, T. F., & Pereira, M. G. (2014). Revisão Sistemática da Literatura: Passos para sua Elaboração. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 23(1), 183-184.

- ABHA – the Multisectoral Association of Water Resources Users of the Araguari River Basin. Dados cobrança federal da água na calha do Rio Paranaíba. Araguari: ABHA. 2021.

- Ladwig, N., da Silva, E., & Back, L. (2017). A Cobrança do Uso da Água e o Impacto no Custo da Produção do Arroz Irrigado na Região Sul do Estado de Santa Catarina. Boletim de Geografia, 35(2), 31. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, K., Moreira, M., & Silva, D. (2018). Cost of Charging for Water Use in the Brazilian Cerrado Hydrographic Basin. Revista Ambiente & Água, 13(5), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Leite, G., & Vieira, W. (2010). Proposta Metodológica de Cobrança pelo Uso dos Recursos Hídricos Usando o Valor de Shapley: Uma Aplicação à Bacia do Rio Paraíba do Sul. Estudos Econômicos - Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas, 40(3), 651-677. [CrossRef]

- Demajorovic, J., Caruso, C., & Jacobi, P. R. (2015). Cobrança do Uso da Água e Comportamento dos Usuários Industriais na Bacia Hidrográfica do Piracicaba, Capivari e Jundiaí. Revista de Administração Pública, 49, 1193-1214. [CrossRef]

- Odppes, R. J., Michalovicz, D. T., & Bilotta, P. (2018). Reuso de Água em Indústria de Fabricação de Estruturas em Concreto: Uma Estratégia de Gestão Ambiental. Revista Tecnologia e Sociedade, 14(34), 82-100.

- Almeida, M., & Curi, W. (2016). Gestão do Uso de Água na Bacia do Rio Paraíba, PB, Brasil com Base em Modelos de Outorga e Cobrança. Revista Ambiente & Água, 11(4), 989-1005. [CrossRef]

- Lima, L., Spletozer, A., Jacovine, L., & Carvalho, A. (2019). Bulk Water Charges in the Dairy Industry: A Case Study of Interstate Basins in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ciência Rural, 49(10), 2-7. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. F. A., & Oliveira-Filho, E. C. (2021). Percepções e Disposição de Agricultores do Distrito Federal sobre Pagamento para Uso de Recursos Hídricos. Ambiente & Sociedade, 24, 2-18. [CrossRef]

- Resende Filho, M., Araújo, F., Silva, A., & Barros, E. (2011). Precificação da Água e Eficiência Técnica em Perímetros Irrigados: Uma Aplicação da Função Insumo Distância Paramétrica. Estudos Econômicos – Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas, 41(1), 143-172. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).