Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Renewable and Sustainable Energy

1.2. Battery Technologies

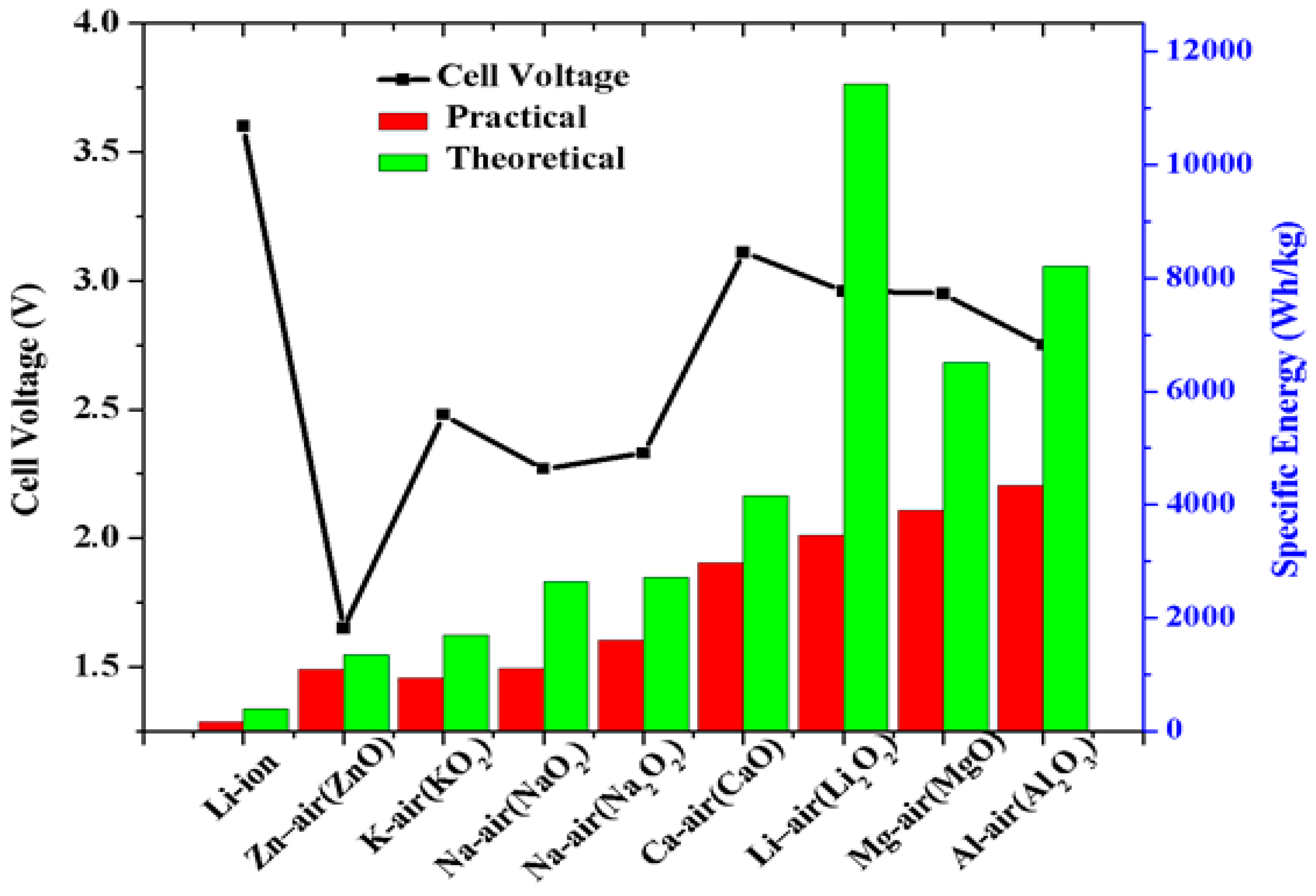

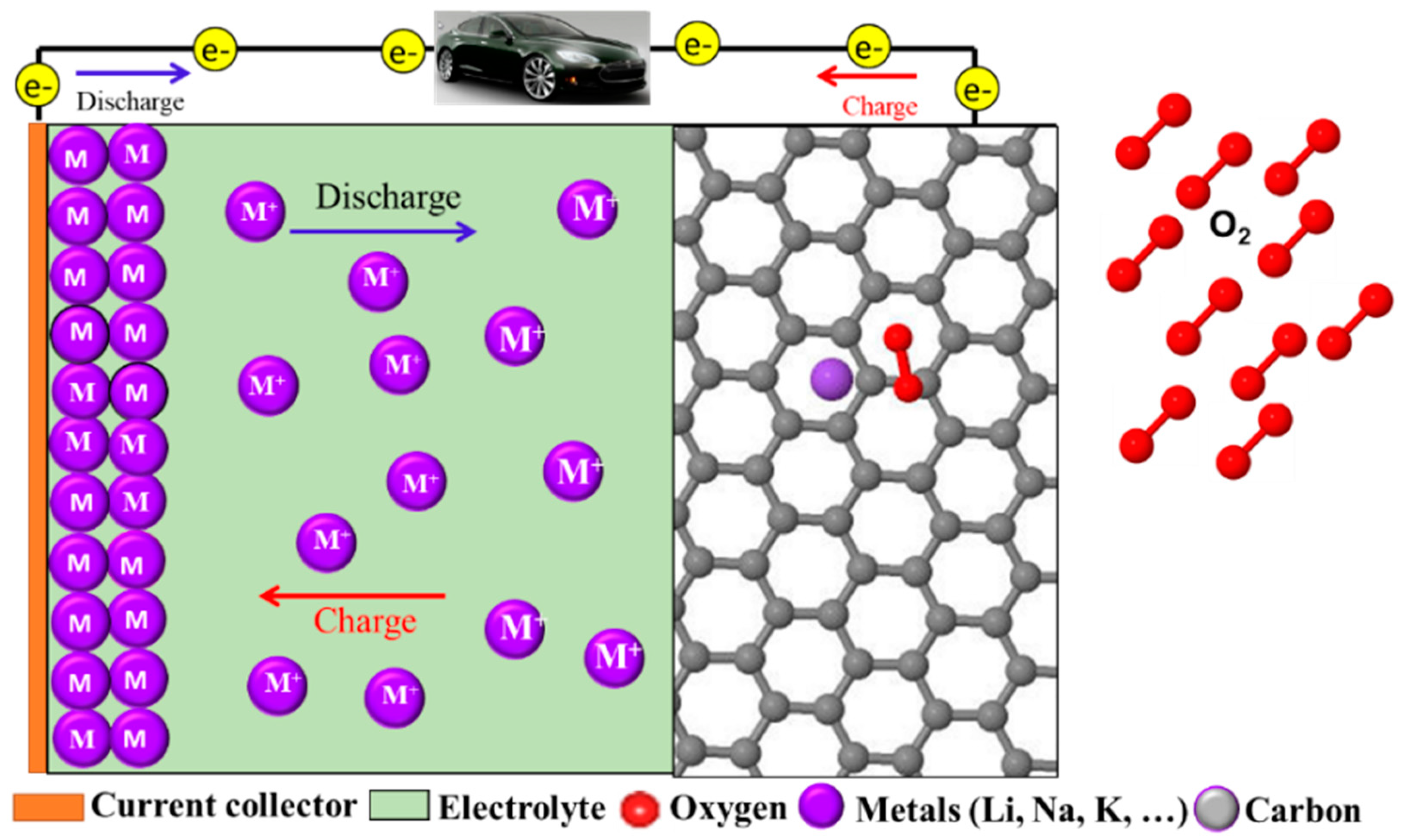

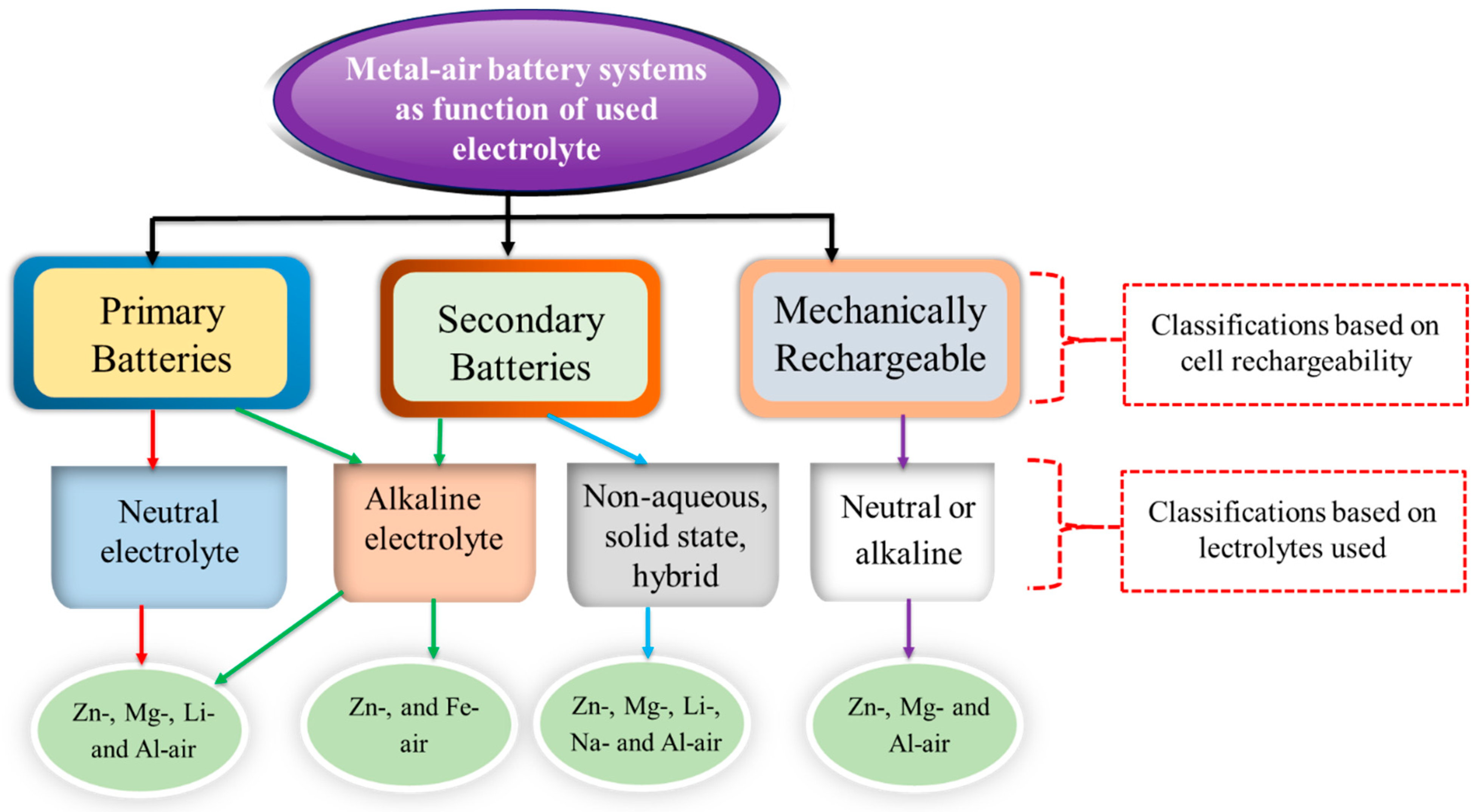

2. Next generation Battery Technologies: Metal Air Batteries

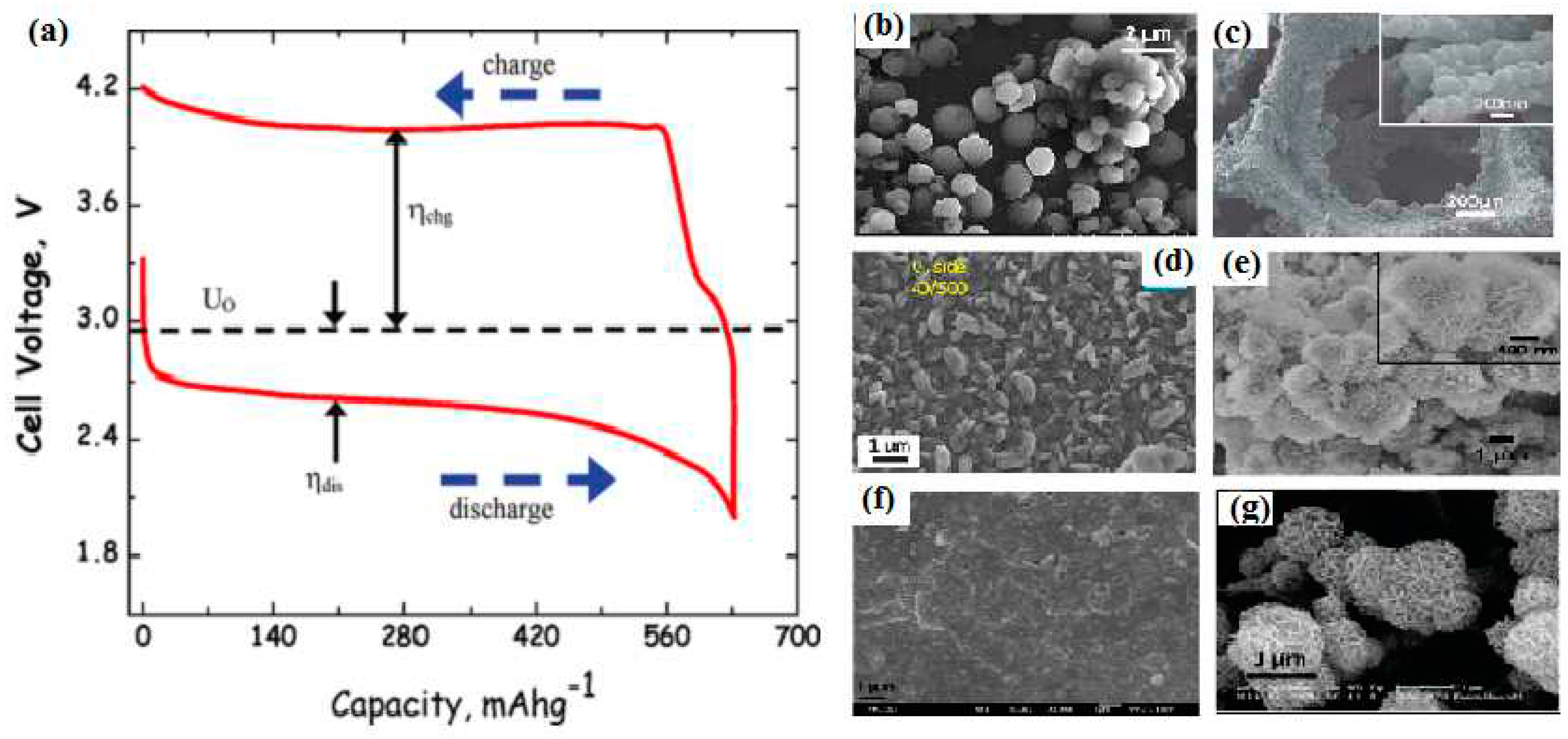

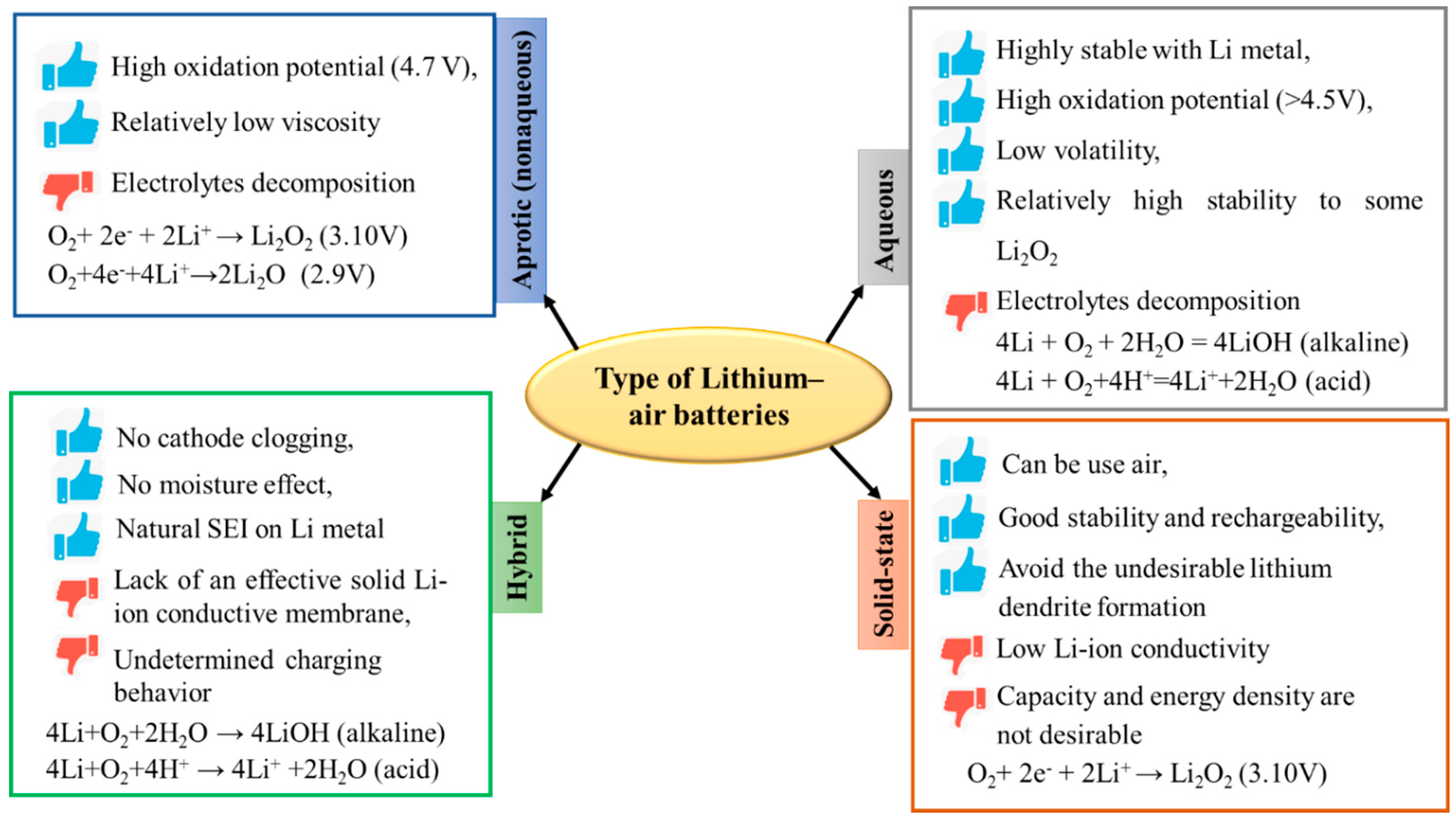

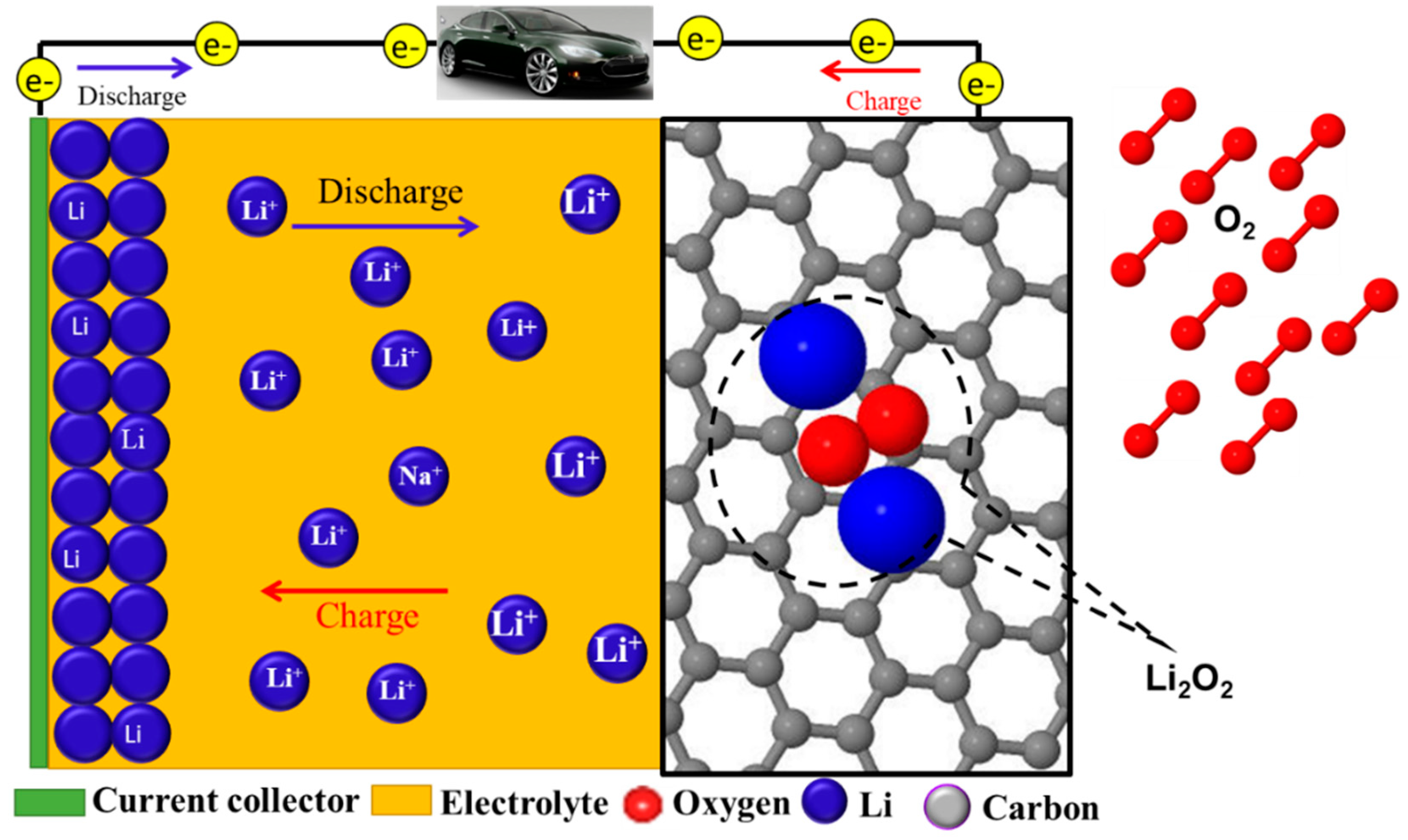

2.1. Non-Aqueous Lithium-O2 Batteries

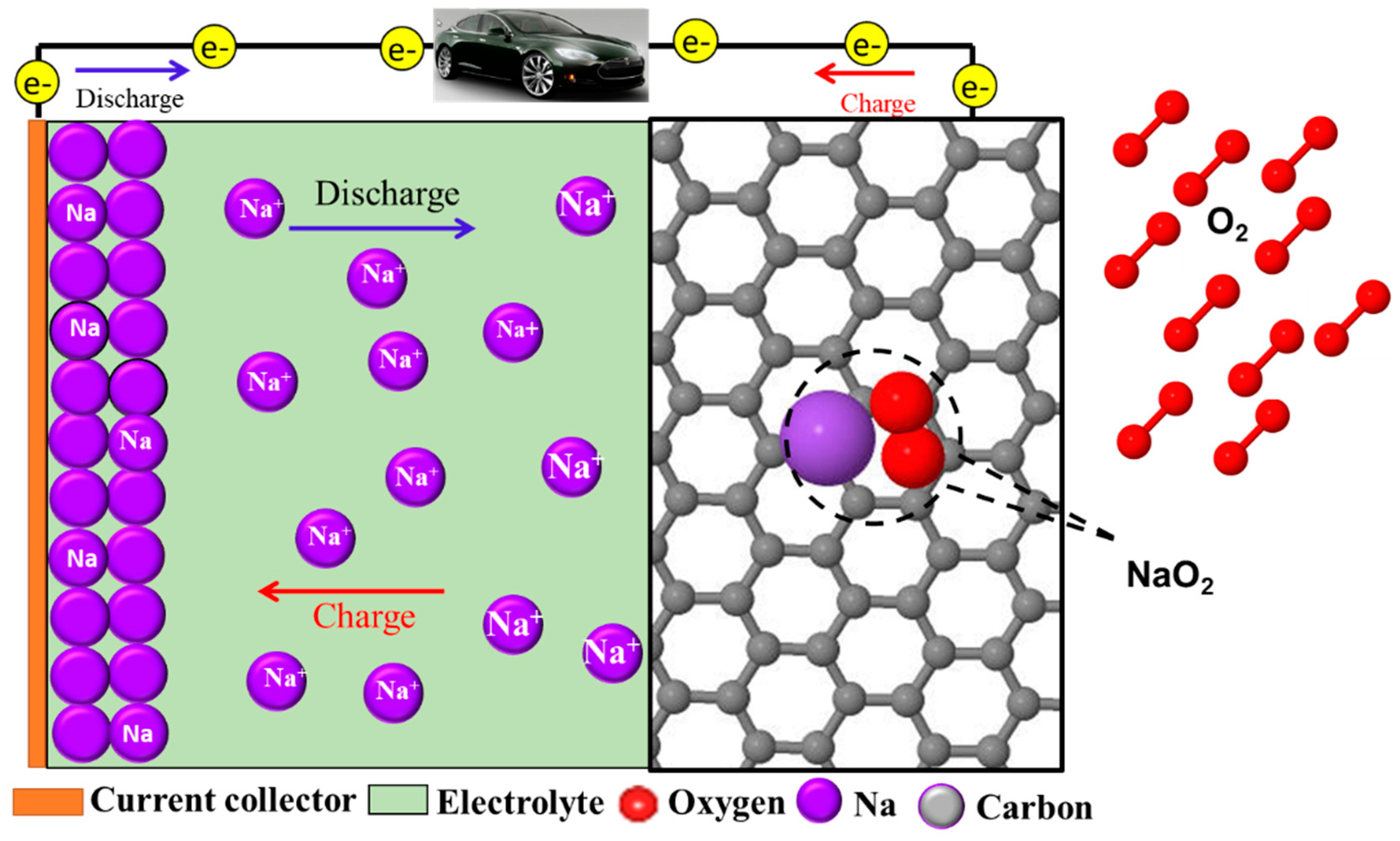

2.2. Non-Aqueous Sodium–O2 Batteries

2.2.1. Electrochemical Reactions and Discharge Products

| Na-O2 | Li-O2 | |

| Cell chemistry | Na+ + O2 + e- →NaO2 2Na+ + O2 + 2e- →Na2O2 |

2Li+ + O2 + 2e- →Li2O2 |

| Cell voltage | E° (2 NaO2) = 2.27 V (ΔG° = -437.5 kJ mol-1) E° (Na2O2) = 2.33 V (ΔG° = -449.7 kJ mol-1) |

E° (Li2O2) = 2.96 V (ΔG° = -570.8 kJ mol-1) |

| Overpotential (Discharge/ Charge) | ηdis < 100 mV ηch ≈ 30-100 mV |

ηdis ≈ 300 mV ηch ≈ 1300 mV |

| Energy density | 1108 Wh kg-1 (NaO2) 1605 Wh kg-1 (Na2O2) |

3458 Wh kg-1 (Li2O2) |

| Theoretical capacity | 1165 mAh g-1 (Na) 488 mAh g-1 (NaO2) 689 mAh g-1 (Na2O2) |

3861 mAh g-1 (Li) 1168 mAh g-1 (Li2O2) |

| OER/ORR efficiency | ~ 78% | ~ 93% |

| Earth Abundance of metal1 |

2.05% | 0.0065% |

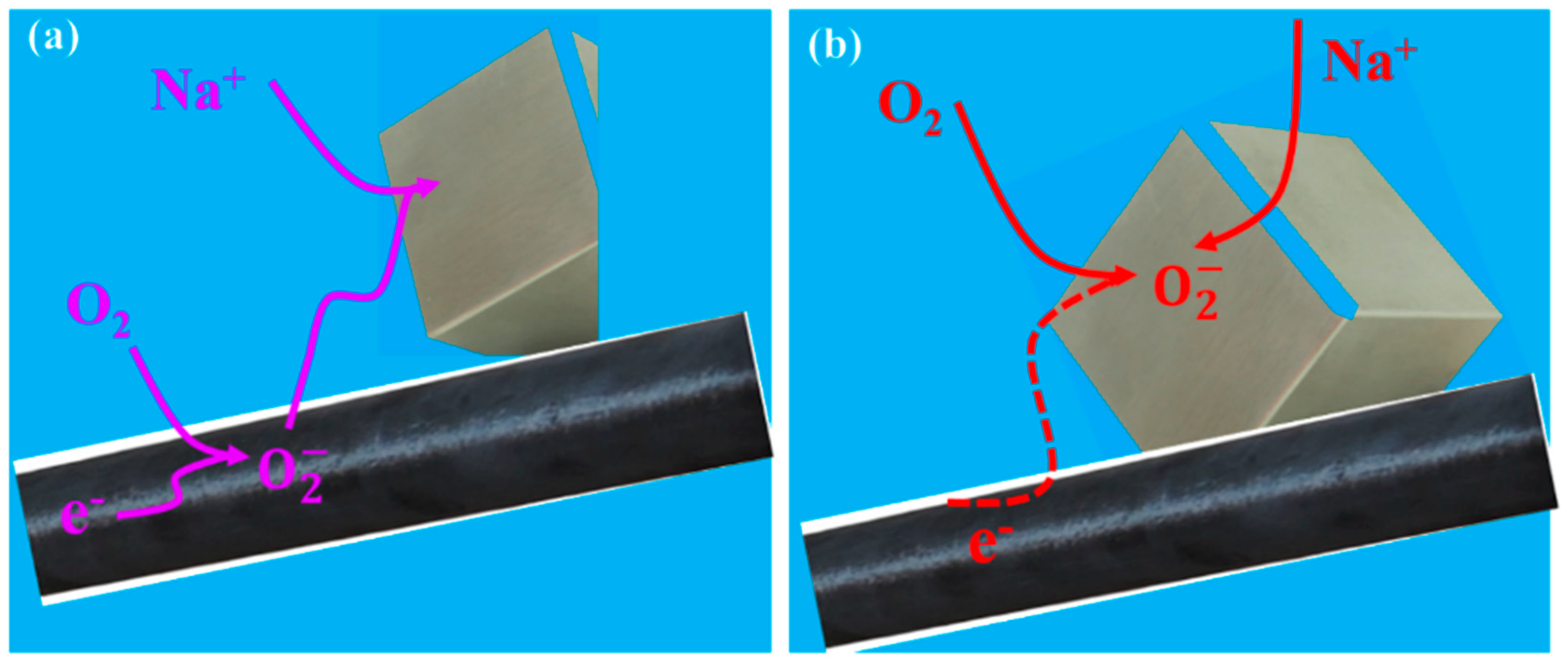

2.2.2. Insight into the Reaction Mechanism in NASAB

3. Challenges in Non-Aqueous Metal-O2/Air Batteries

3.1. Decomposition of the electrolyte

3.2. Degradation of the carbon cathode

3.3. Anodic Dendrite Growth

3.4. Air Impurities

4. Conclusions and outlooks

- Developing and synthesizing an innovative porous carbon material with enhanced conductivity, enabling the creation of an adequate and suitable three-phase interface that promotes effective charge/discharge processes

- Identifying bifunctional cathode catalysts with enhanced activity for both the ORR during discharge and the OER during charge to achieve a high round-trip efficiency.

- Designing stable electrolytes characterized by high oxygen (O2) solubility, enhanced ionic conductivity, low viscosity, and minimal vapor pressure.

- Creating a high metal ionic conducting separator and a high-throughput oxygen-breathing membrane utilized at the cathode to block H2O, CO2, and other air components except O2.

- Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the intricate chemical reaction mechanisms occurring during charge and discharge.

References

- Ipcc, “Summary for Policy Makers”. Climate Change : Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability - Contributions of the Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report, 2014. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/.

- Y.S. Mekonnen, Computational Analysis and Design of New Materials for Metal - Air Batteries, PhD thesis, Department of Energy Conversion and Storage, Technical University of Denmark, 2015.

- R. Christensen, T. Vegge, H.A. Hansen, Error Mitigation in Computational Design of Sustainable Energy Materials, PhD thesis, Department of Energy Conversion and Storage, Technical University of Denmark, 2017.

- S. Prasad, S. Radhakrishnan, S. Kumar, S. Kannojia, Chapter 9 Sustainable Energy : Challenges and Perspectives, in: Sustain. Green Technol. Environ. Manag., Springer Nature, Singapore, 2019: pp. 175–197.

- REN21, Renewables 2019 global status report, REN21 Secretariat, Paris: REN21 Secretariat, 2019. https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/report/renewables-2019-global-status-report.

- G.A. Tiruye, A.T. Besha, Y.S. Mekonnen, N.E. Benti, G.A. Gebreslase, R.A. Tufa, Opportunities and Challenges of Renewable Energy Production in Ethiopia, Sustain. 13 (2021) 10381. [CrossRef]

- N.E. Benti, G.S. Gurmesa, T. Argaw, A.B. Aneseyee, S. Gunta, G.B. Kassahun, G.S. Aga, A.A. Asfaw, The current status , challenges and prospects of using biomass energy in Ethiopia, Biotechnol. Biofuels. 14 (2021) 209. [CrossRef]

- IRENA, Renewable Energy Technologies: Cost Analysis Series, 2012. https://irena.org/publications/2012/Jun/Renewable-Energy-Cost-Analysis Series.

- IEA, Energy and Climate Change, 2015. https://webstore.iea.org/weo-2015-special-report-energy-and-climate-change.

- A.K. Shukla, T.P. Kumar, Materials for next-generation lithium batteries, Curr. Sci. 94 (2008) 314–331. [CrossRef]

- M. Armand, U. De Picardie, J. Verne, J. Tarascon, Building Better Batteries, Nature. 451 (2008) 652–657. [CrossRef]

- J.B.A. Mizushima, K.; Jones, P. C.; Wiseman, P. J.; Goodenough, New Cathode Material for Batteries of High Energy Density, Solid State Ionics. North-Holl. Publ. Co. 4 (1981) 171–174.

- D. Linden, T.B. Reddy, Handbook of Batteries, 3rd edit, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001.

- Tesla Motors Inc., Tesla Motors – 2015 Report, (2015). http://ir.tesla.com.

- P.G. Bruce, S.A. Freunberger, L.J. Hardwick, J.M. Tarascon, Li–O2 and Li–S batteries with high energy storage, Nat. Mater. 11 (2012) 19–30. [CrossRef]

- B. Nykvist, M. Nilsson, Rapidly falling costs of battery packs for electric vehicles, Nat. Clim. Chang. 5 (2015) 100–103. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Thackeray, C. Wolverton, E.D. Isaacsc, Electrical energy storage for transportation—approaching the limits of, and going beyond, lithium-ion batteries, Energy Environ. Sci. (2012) 7854–7863.

- N.E. Benti, Y.S. Mekonnen, R. Christensen, G.A. Tiruye, J.M. Garcia-lastra, T. Vegge, The effect of CO2 contamination in rechargeable non-aqueous sodium – air batteries, J. Chem. Phys. 152 (2020) 074711. [CrossRef]

- N.E. Benti, G.A. Tiruye, Y.S. Mekonnen, Boron and pyridinic nitrogen-doped graphene as potential catalysts for rechargeable non-aqueous sodium-air batteries, RSC Adv. 10 (2020) 21387–21398. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Abraham, Z. Jiang, A Polymer Electrolyte-Based Rechargeable lithium / Oxygen Battery, Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 143 (1996) 1–5. [CrossRef]

- P. Hartmann, C.L. Bender, M. Vraˇ, A.K. Dürr, A. Garsuch, J. Janek, P. Adelhelm, A rechargeable room-temperature sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery, Nat. Mater. 12 (2012) 228–232. [CrossRef]

- K.B. Knudsen, J.E. Nichols, T. Vegge, A.C. Luntz, B.D. Mccloskey, J. Hjelm, An Electrochemical Impedance Study of the Capacity Limitations in Na-O2 Cells, J. Phys. Chem. C. 120 (2016) 10799–10805. [CrossRef]

- H. Arai, Metal Storage / Metal Air ( Zn , Fe , Al , Mg ), in: P.T. Moseley, J. Garche (Eds.), Electrochemical Energy Storage for Renewable and Grid Balancing, in: Electrochem. Energy Storage Renew. Sources Grid Balanc., Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, 2015: pp. 337–344.

- P.O. M. Pino, D. Herranz, J. Chacon, E.Fatas, Carbon treated commercial aluminium alloys as anodes for aluminium-air batteries in sodium chloride electrolyte, J. Power Sources. 326 (2016) 296–302. [CrossRef]

- M. Balaish, Y. Ein-eli, A critical review on lithium – air, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16 (2014) 2801–2822.

- Z. Ma, X. Yuan, L. Li, Z.-F. Ma, D.P. Wilkinson, L. Zhang, J. Zhang, A review of cathode materials and structures for rechargeable lithium-air batteries, Energy Environ. Sci. 8 (2015) 2144–2198. [CrossRef]

- M.D. Radin, First-Principles and Continuum Modeling of Charge Transport in Li-O2 Batteries, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53 (2013) 1689–1699.

- J.S. Lee, S.T. Kim, R. Cao, N.S. Choi, M. Liu, K.T. Lee, J. Cho, Metal-air batteries with high energy density: Li-air versus Zn-air, Adv. Energy Mater. 1 (2011) 34–50. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Y. Li, X. Sun, Challenges and opportunities of nanostructured materials for aprotic rechargeable lithium-air batteries, Nano Energy. 2 (2013) 443–467. [CrossRef]

- Eunjoo Yoo and Haoshen Zhou, Li - Air Rechargeable Battery Based on Metal-free Graphene Nanosheet Catalysts, ACS Nano. 5 (2011) 3020–3026. [CrossRef]

- P.H. and H.Z. Yonggang Wang, A lithium–air capacitor–battery based on a hybrid electrolyte, Energy Environ. Sci. (2011) 4994–4999.

- B. Kumar, J. Kumar, R. Leese, J.P. Fellner, S.J. Rodrigues, K.M. Abraham, A. Force, P. Directorate, W.A.F. Base, A Solid-State , Rechargeable , Long Cycle Life Lithium – Air Battery, J. Electrochem. Soc. 157 (2010) A50–A54.

- S.S. Zhang, D. Foster, J. Read, Discharge characteristic of a non-aqueous electrolyte Li/O2 battery, J. Power Sources. 195 (2010) 1235–1240. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Whittingham, Lithium Batteries and Cathode Materials, Chem. Rev. 104 (2004) 4271−4301. [CrossRef]

- P. Hartmann, C.L. Bender, J. Sann, A.K. Dürr, M. Jansen, J. Janek, P. Adelhelm, A comprehensive study on the cell chemistry of the sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. . 15 (2013) 11661–72. [CrossRef]

- P. Hartmann, C.L.. Bender, M. Vračar, A.K. Dürr, A. Garsuch, J. Janek, P. Adelhelm, A rechargeable room-temperature sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery, Nat. Mater. 12 (2013) 228–232. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhao, C. Li, X. Guo, Long-life Na-O₂ batteries with high energy efficiency enabled by electrochemically splitting NaO₂ at a low overpotential., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16 (2014) 15646–15652. [CrossRef]

- Y.S. Mekonnen, R. Christensen, J.M. García-Lastra, T. Vegge, Thermodynamic and Kinetic Limitations for Peroxide and Superoxide Formation in Na − O2 Batteries, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9 (2018) 4413–4419. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Mccloskey, J.M. Garcia, A.C. Luntz, Chemical and Electrochemical Differences in Nonaqueous Li-O₂ and Na-O₂ Batteries, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5 (2014) 1230–1235. [CrossRef]

- S.M.B. Khajehbashi, L. Xu, G. Zhang, S. Tan, L. Wang, J. Li, W. Luo, D. Peng, L. Mai, High-performance Na-O2 Battery Enabled by Oriented NaO2 Nanowires as Discharge Products, Nano Lett. 18 (2018) 3934–3942. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, H. Lim, H. Gwon, K. Kang, Sodium–oxygen batteries with alkyl-carbonate and ether based electrolytes, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (2013) 3623–3629. [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, Q. Sun, Y. Yang, J.-Y. Xie, Z.-W. Fu, An enhanced electrochemical performance of a sodium-air battery with graphene nanosheets as air electrode catalysts., Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 1951–3. [CrossRef]

- S.K.. Das, S. Lau, L.A.. Archer, Sodium–oxygen batteries: a new class of metal–air batteries, J. Mater. Chem. A. 2 (2014) 12623–12629.

- Z. Jian, Y. Chen, F. Li, T. Zhang, C. Liu, H. Zhou, High capacity Na-O2 batteries with carbon nanotube paper as binder-free air cathode, J. Power Sources. 251 (2014) 466–469. [CrossRef]

- H. Yadegari, Y. Li, M.N. Banis, X. Li, B. Wang, Q. Sun, R. Li, T. Sham, X. Cui, X. Sun, On rechargeability and reaction kinetics of sodium–air batteries, Energy Environ. Sci. 7 (2014) 3747–3757. [CrossRef]

- B.D. McCloskey, J.M. Garcia, A.C. Luntz, Chemical and electrochemical differences in nonaqueous Li-O₂ and Na-O₂ batteries, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5 (2014) 1230–1235. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, D.J. Siegel, Intrinsic Conductivity in Sodium-air Battery Discharge Phases: Sodium Superoxide vs. Sodium Peroxide, Chem. Mater. 27 (2015) 3852−3860. [CrossRef]

- W. Yin, Z. Fu, The Potential of Na – Air Batteries, ChemCatChem. 9 (2017) 1545–1553. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Luntz, B.D. Mccloskey, Nonaqueous Li − Air Batteries : A Status Report, Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 61–67. [CrossRef]

- E. Peled, D. Golodnitsky, R. Hadar, H. Mazor, M. Goor, L. Burstein, Challenges and obstacles in the development of sodium e air batteries, J. Power Sources. 244 (2011) 771–776. [CrossRef]

- S. Kang, Y. Mo, S.P. Ong, G. Ceder, Nanoscale Stabilization of Sodium Oxides: Implications for Na − O2 Batteries, Nano Lett. 14 (2014) 1016−1020. [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, Q. Sun, Y. Yang, J. Xie, Z. Fu, An enhanced electrochemical performance of a sodium–air battery with graphene nanosheets as air electrode catalysts, Chem Comm. 49 (2013) 1951–1953.

- B. Lee, D. Seo, H. Lim, I. Park, K. Park, J. Kim, K. Kang, First-Principles Study of the Reaction Mechanism in Sodium−Oxygen Batteries, Chem. Mater. 26 (2014) 1048−1055. [CrossRef]

- Q. Sun, Y. Yang, Z. Fu, Electrochemical properties of room temperature sodium – air batteries with non-aqueous electrolyte, Electrochem. Commun. 16 (2012) 22–25. [CrossRef]

- N. Ortiz-vitoriano, T.P. Batcho, D.G. Kwabi, B. Han, N. Pour, C. V Thompson, Y. Shao-horn, Rate-Dependent Nucleation and Growth of NaO2 in Na−O2 Batteries, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6 (2015) 2636–2643. [CrossRef]

- R. Black, S.H. Oh, J. Lee, T. Yim, B. Adams, L.F. Nazar, Screening for superoxide reactivity in Li-O2 batteries: effect on Li2O2/LiOH crystallization., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 2902–2905. [CrossRef]

- F. Mizuno, S. Nakanishi, A. Shirasawa, K. Takechi, T. Shiga, H. Nishikoori, H. Iba, Design of Non-aqueous Liquid Electrolytes for Rechargeable Li-O2 Batteries, Electrochemistry. 79 (2011) 876–881. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Freunberger, Y. Chen, N.E. Drewett, L.J. Hardwick, F. Bardé, P.G. Bruce, The lithium-oxygen battery with ether-based electrolytes, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 8609–8613. [CrossRef]

- B.D. McCloskey, A. Speidel, R. Scheffler, D.C. Miller, V. Viswanathan, J.S. Hummelshøj, J.K. Nørskov, A.C. Luntz, Twin problems of interfacial carbonate formation in nonaqueous Li-O2 batteries, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3 (2012) 997–1001. [CrossRef]

- N. Imanishi, A.C. Luntz, P. Bruce, The Lithium Air Battery : Fundamentals, Springer, New York, 2014.

- R. Black, A. Shyamsunder, P. Adeli, D. Kundu, G.K. Murphy, L.F. Nazar, The Nature and Impact of Side Reactions in Glyme-based Sodium–Oxygen Batteries, ChemSusChem. 9 (2016) 1795–1803. [CrossRef]

- D. Geng, N. Ding, T.S.A. Hor, S.W. Chien, Z. Liu, D. Wuu, X. Sun, Y. Zong, From Lithium-Oxygen to Lithium-Air Batteries: Challenges and Opportunities, Adv. Energy Mater. 6 (2016) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, X. Liu, Y. Jiang, J. Li, J. Ding, W. Hu, C. Zhong, Recent advances and challenges in divalent and multivalent metal electrodes for metal-air batteries, J. Mater. Chem. A. 7 (2019) 18183–18208. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).