1. Introduction

In these uncertain times, discerning “what is next” for the higher education sector will likely require calculated speculation and some risk-taking. It is imperative to note that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only created severe short-term financial and operational challenges for colleges and universities, but it further accelerated the impact of demographic, financial, technological, and political trends long affecting the sector. While lecturers remain committed to their institutions’ core missions in the face of these challenges, now is the right time to reconsider value propositions and operating models considering new realities. This paper produced this report to help institutions navigate the uncertainties ahead.

The new urgency for remote teaching caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity for the country to adopt policies to accelerate blended learning practices among lecturers and students. With higher education (HE) academic programmes offered entirely online because of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, large-scale change has been required of academic staff who design and present the programmes and of the students who undertake them.

On-campus face-to-face teaching will most likely return when the pandemic abates, providing the social-cultural elements of the teacher, the learning environment, technology, learning activities, and peers that in undergraduate education support effective student engagement (Crosling et al., 2008; Tay et al., 2021) and students’ development of higher-level skills such as problem-solving and technical skills.

It is interesting to note that during the pandemic, students’ preferences for online compared with face-to-face shifted worldwide: 78% of tertiary students in Malaysia, 83% in Canada, and 78% in China indicated a preference for online learning if the programme fees are reduced accordingly (Karupiah, 2021). Globally, online learning as the panacea during the pandemic (Dhawan, 2020; AyebiArthur, 2017) was seen in Singapore with the government’s requirement of it for the education sector including higher education institutions (HEIs) (Lai, 2021). Post-COVID-19, however, it is expected that the new educational model to emerge (Kandri, 2020) is blended learning (BL) which melds face-to-face teaching with online tools (Alammary et al., 2014), bridging COVID-19 fully online learning and on-campus face-to-face learning (Kandri, 2020).

Emerging from this in-depth study of the uses and perspectives of academic staff with Blended Learning in a Singaporean HEI, the systematic group of elements that constitute a BL ecosystem is identified. This ecosystem that demonstrates flexibility can guide Blended Learning development in HEIs in Singapore, and globally. The Science Foundation lecturers seemed to experience challenges in various online learning platforms as the assessments were to be given and graded on the Moodle LMS.

Moreover, the academics at one of the South African rural universities constantly raise concerns regarding the Moodle platform in mathematics and science-related modules due to unduly accommodation in the assessments uploaded on the platform. While the institution encourages academics to regularly use Moodle over the other platforms to integrate online classes and assessments. Moreover, the assessments are mostly not easy to mark on the platform.

2. Purpose of the Paper

The purpose of the paper is to examine the academics’ perspectives on a blend of a metaverse in the higher education sector in the post-COVID-19 era at one of the South African rural universities.

- 1

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- •

What were the major challenges encountered during the online classes in the COVID-19 era?

- •

How do Academics perceive the continuity of online learning as the new norm in higher education?

- 2

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Connectivism was first introduced in 2004 in a blog post which was later published as an article in 2005 by George Siemens. It was later expanded in 2005 by two publications, Siemens’ Connectivism: Learning as Network Creation and Downes’ An Introduction to Connective Knowledge. Both works received significant attention in the blogosphere and an extended discourse has followed on the appropriateness of connectivism as a learning theory for the digital age. In 2007, Bill Kerr entered the debate with a series of lectures and talks on the matter, as did Forster, both at the Online Connectivism Conference at the University of Manitoba. In 2008, in the context of digital and e-learning, connectivism was reconsidered and its technological implications were discussed by Siemens and Ally.

Moreover, this theoretical framework is employed in this paper because it focuses on understanding learning in a digital age. It emphasizes how internet technologies such as web browsers, search engines, wikis, online discussion forums, and social networks contributed to new avenues of learning. As technologies have enabled academics to learn and share information across the World Wide Web and among themselves in ways that were not possible before the digital age.

Learning does not simply happen within an individual, but within and across the networks. Connectivism sees knowledge as a network and learning as a process of pattern recognition. The phrase "a learning theory for the digital age indicates the emphasis that connectivism gives to technology's effect on how people live, communicate, and learn.

3. Material and Methods

In this paper, a qualitative method was employed, whereby the survey questionnaire was later quantified to determine the degree of the problem and predominant of these issues and challenges from academics’ responses. Miles et al. (2014) and Kuper et al. (2008) attest to the significance of employing a qualitative data collection approach as being immensely effective in study fields such as education, sociology, and anthropology. Most significantly, the utilization momentum of this approach has been gained in the health professions and education fields. This method was used to obtain descriptive and numerical data from the respondents, and this included frequency counts and percentages to determine the most common perspectives and challenges related to the questions.

The researchers employed a purposive sampling technique because the participants were in the interest of the researcher’s criteria as they made use of technological devices during the hard lockdown period and navigated through the online space. The sample included a total of ten (10) academic staff from different departments within the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture and the 4 E-learning practitioners at the University of Venda and they were all requested to participate in the study simply by completing the questionnaire and narratives.

However, only 10 academics and 4 E-learning practitioners completed out of the entire population of students responded to the survey questionnaire and this survey was aimed at assessing student participation and experiences while attending online lectures on various platforms. The data collected for this study were analysed using thematic coding, with researchers going through the responses carefully to classify the data into topics and further understand the perspectives of academics on the usage of technology beyond the COVID-19 era in higher education institutions at a rural university. The researchers analysed publicly available data, surveys, and interviewed lecturers and e-learning practitioners at one of the rural universities in the South African higher education sector to large flagship public universities.

4. Results and Discussion

The findings of this study exhibit that there are major issues and challenges that many academics and E-learning practitioners are encountering regarding the integration of blended learning possible as the new norm even in the post-COVID-19 era in Higher Education. Technological continuity as a new normal in the post-COVID-19 era seems to be unattainable.

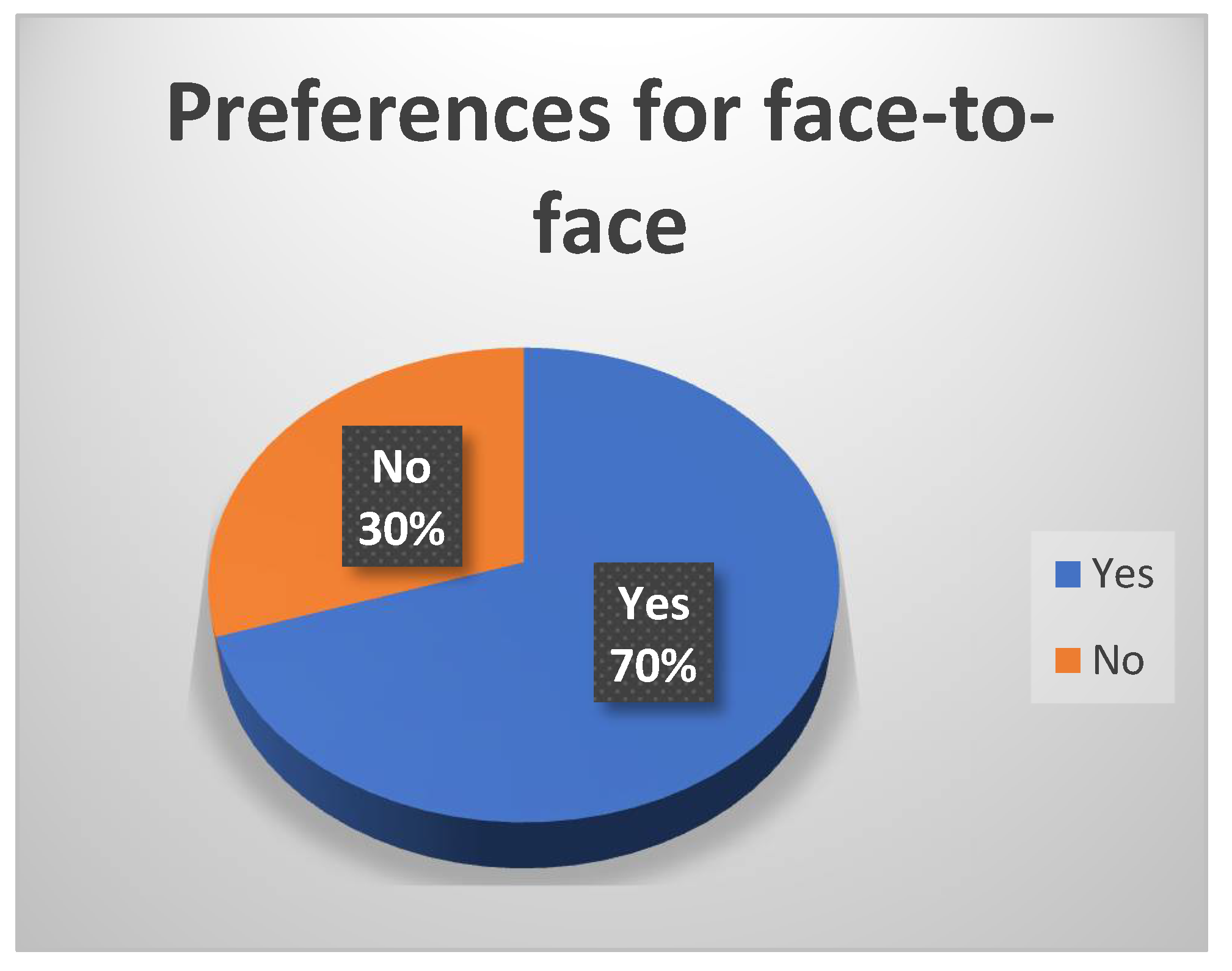

Figure 1.

Lecturers’ face-to-face preferences.

Figure 1.

Lecturers’ face-to-face preferences.

The lecturers indicated that the assessments will forever need a physical setting, not an online space, particularly in rural-based institutions whereby network towers seem to be a major conundrum for students from remote areas. Some honestly indicated that they are reluctant to undergo proper training for Moodle and other online platforms and their students were mostly unable to engage in the ongoing discussion during the session.

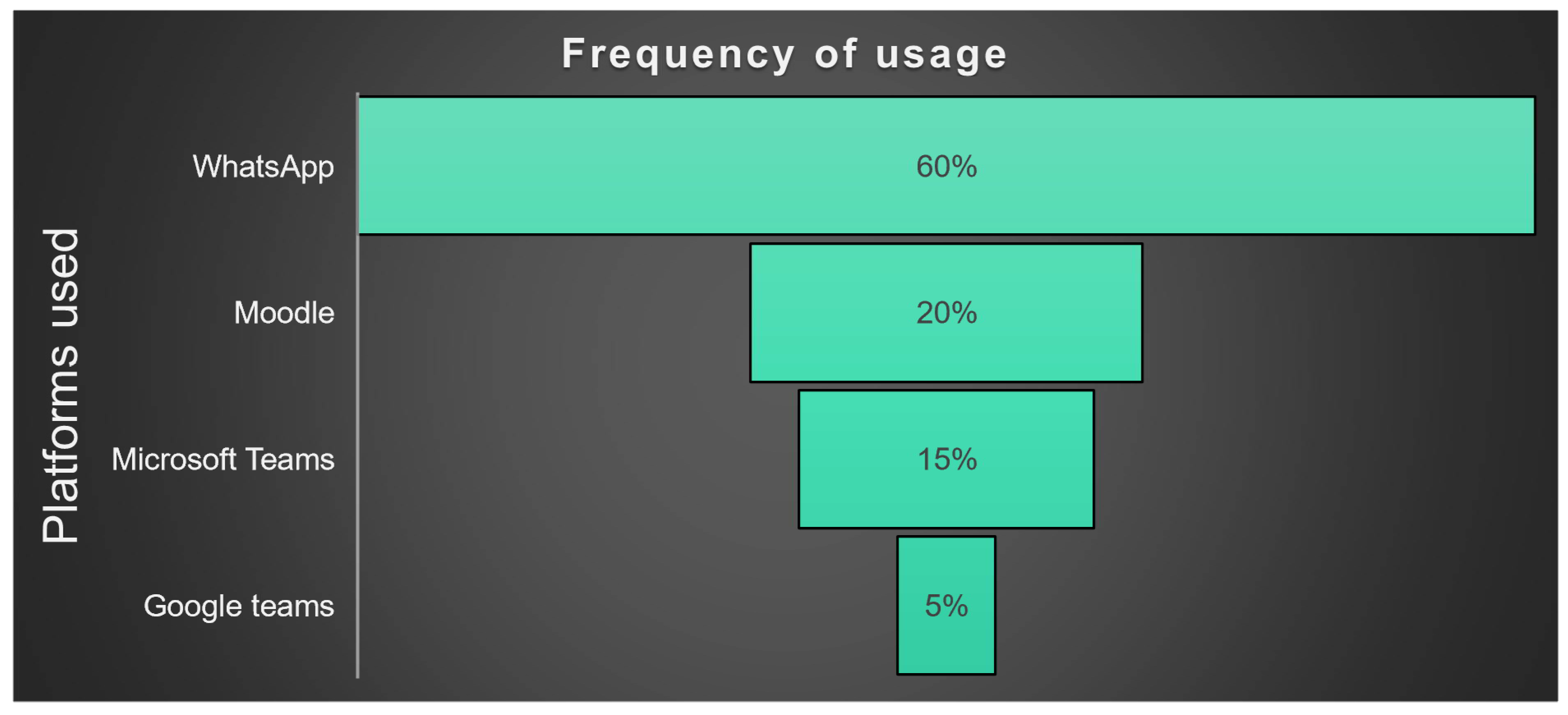

Figure 2.

Frequency of use of online platforms by academics.

Figure 2.

Frequency of use of online platforms by academics.

Some academics narrated that face-to-face is better than online owing to the fact one can monitor students who attend the classes while on the platform, it is difficult for the academics to trace the students who are actively engaging in the content and those who are only available for compliance.

The academics indicated the platforms that they used to supplement their teaching and learning with the students if they are not available on campus for contact sessions. The academics used WhatsApp more than the other platforms due to students’ data challenges as they are presently not receiving anything from the institution. Moreover, the computer labs were not accessible to the students, and they had problems with the lack of devices for online classes. The students supported the use of WhatsApp while considering their financial circumstances and lack of technological devices to attend online classes and network connectivity problems in the comfort of their learning space.

This resonates with Attard (2015) articulated in his study that online learning depends on the technologies used at the time and the curriculum that is being taught. The researchers suggest that the platforms and different approaches should be integrated to achieve maximum learning.

Usage of the Learning Management System between Students and Academics

The e-learning practitioners expressed their concerns and major conundrums during their training and daily consultation with the academics and students. The students’ daily consultation had common problems which among others encompass network connectivity, struggling to login into the Moodle LMS, and inaccessibility to the assessments uploaded by their module lecturers. Furthermore, E-learning practitioners further elucidated that academics have challenges concerning marking assessments and providing feedback on the platform due to inadequate mastery of the platform operation and navigation skills. This study is validated by the findings of Jacobs (2013) who elucidated that it is imperative to recognize the type of student enrolled in the course to design a suitable interaction system that enables the students not only to learn but even to interact among themselves.

Complacency in the Online Setting

The biggest problem among others is complacency in the online setting and the academics tend to think that the online platform is conformable to constantly facilitate the online classes while many students are mostly not participating and only available for compliance and procedural record keeping. Over and above, online classes have proven not to be solely independent due to the higher number of students who are not capacitated, and this poses an academic trajectory in many institutions. This study concurs with Hwakoh (2020) who pinpointed that face-to-face teaching has received strong support from students at all levels and has been viewed as more effective than online interaction as the lecturers and students tend to experience challenges.

Fixed Mindset and Expectation

Most academics believed that contact learning remains irreplaceable throughout generations and ages as some are technophilic. This study is incongruent with the findings of Liu and Long (2014), the study outlined that face-to-face learning is irreplaceable and a cornerstone of any learning institution, even if the current discourse and technological revolution require the use of eLearning. Moreover, online learning was and is still an effective approach to meet the accelerated demands of the diverse student population in universities and colleges.

Resistance to Using Technology.

The e-learning practitioners who were interviewed about their perceptions of the continuous usage of technology in the higher education sector in the post-COVID-19 era indicated that the academics deteriorated the use of blended learning in their respective programmes. This has been necessitated by the adjustment of COVID-19 regulations imposed on the indoor gathering capacity wherein there is a resurgence in COVID-19 cases. The findings of this study are consistent with Gillett-Swan (2018) articulated that a major challenge for online learning is the one size fits all approach, which does not do justice to student differences. Online learning should be integrated with contact sessions to mitigate decontextualised teaching classrooms.

Lack of Technological Skills

Most lecturers stated that they are not well equipped with the technological devices usually used for online teaching and learning environment. As academic institutions were impelled by the COVID-19 pandemic to integrate technology when facilitating lessons. Most academics made use of social media platforms to compensate for their incompetency with Moodle utilization. There is a need for academics to be well-trained to use technology skilfully and excellently. This study corroborates with Gillett-Swan (2017) espoused that technology is expected to improve access to education, reduce costs, improve the cost-effectiveness of education, and maintain the competitive advantage in recruiting students in higher education.

5. Conclusion

Fully manifestation of technology as the new norm in the post-COVID-19 era seems not to be practically attainable owing to the challenges and issues expressed by academics and E-learning specialists. This is a prevalent area of importance because the emergency of the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the challenges in teaching and learning due to the distanced interaction.

Conversely, it is imperative to note the online space was seen as a temporary learning environment because most lecturers seem not to welcome blended learning beyond the harsh COVID-19 restrictions. Even though there is a paradigm shift in terms of teaching and learning approaches.

Most academics believed that contact learning remains irreplaceable throughout generations and ages as some are technophilic. Most academics made use of social media platforms to compensate for their incompetency with Moodle utilisation.

Recommendations and Implications for Practice

The policy must be implemented on the minimal online presence by the academics and students to enhance the usage of the platform.

The Moodle Training should be made compulsory for both students and academics to equip them with the fundamental skills on the usage.

The formative assessments should be taken to the online platform in a semester in each module. The retention center should be used to track the student’s active participation on the platform.

The lack of access to devices should not be used as a stumbling block to consider e-learning as a viable option to continue with education. The connectivity challenge in rural areas should not be used as a reason to ignore the significant potential of e-learning as an enabler to access and advance education.

References

- Alammary, A. , Sheard, J. and Carbone, A. Blended learning in higher education: Three different design approaches. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 2014; 30. [Google Scholar]

- Crosling, G. , Edwards, R. and Schroder, B. Internationalizing the curriculum: The implementation experience in a faculty of business and economics. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2008, 30, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett-Swan, J. The Challenges of Online Learning Supporting and Engaging the Isolated Learner. Journal of Learning Design. Special Issue: Business Management. 2017, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwakoh, Y. Internet-based distance learning in higher education. Tech Directions. 2020, 62, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, D. Teaching responsibility through physical activity, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2013.

- Kandri, J. Josip Marić, Isabelle Gama-Araujo. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic in education and vaccine hesitancy among students: A cross-sectional analysis from France. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 2020; 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, A. , Lingard, L. and Levinson, W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ, 2008; 337. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J and Long, Y. Critical thinking and the disciplines reconsidered. Higher Education Research and Development 2014, 32, 529–544. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, E. , Crisp, R. J., and Husnu, S. Support for the replicability of imagined contact effects. Social Psychology 2014, 45, 303–304. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, D and Attar, E. Digital natives come of age: The reality of today’s early career teachers using mobile devices to teach mathematics: Mathematics Education Research Journal 2015, 28, 107–121.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).