1. Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a growing global health problem. Several factors such as the use of fungicides in agriculture, the development of new immunosuppressive therapies, biological and cytotoxic drugs, the increase in the number of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT) and the growing use of invasive biomedical devices such as intravascular catheters have contributed to this situation [

1]. Historically, systemic infection of Candida spp., with or without associated candidiasis, was the most common IFI in patients with hematologic malignancies (HM) in our latitudes. However, in recent decades, there has been a decrease caused by the current effectiveness of azole antifungal prophylaxis [

2]. In contrast, the incidence of IFI due to Aspergillus spp. and other filamentous fungi has increased [

3].

Aspergillus spp. is a filamentous hyaline fungus that is widely distributed in nature. Its natural habitat is the soil, which allows it to be isolated from the soil and dust. More than 300 species of Aspergillus are known, of which only a small number of it cause opportunistic infections in humans. Aspergillus fumigatus is the specie that causes infection most frequently in humans. This is due to its small spore size of 2-3 microns and its higher thermotolerance with a germination capacity between 37 ° C and 40 ° C. These characteristics optimize its pathogenicity [

3,

4]. However, there are other species of Aspergillus spp. that cause infection, such

as A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus, A. nidulans and

A. lentulus, that are becoming increasingly common, depending on geographical factors, host type and antifungal prophylaxis used [

3,

5].

People with HM are the most susceptible group to suffer an IFI, both in the adult and pediatric population. Specifically, invasive aspergillosis (IA) is the most common invasive fungal infection for patients with acute hematologic malignancies [

5]. Multiple risk factors are involved in the development of IA in patients with HM [

6]. Many of them are related to patients’ characteristics, such as: i) neutrophils < 500 per mm3 and neutropenia time greater than 10 days [

7], ii) being older than 65 years [

4,

5], iii) genetic polymorphisms associated with immune response [

5,

6,

7,

8], iv) type of neoplastic disease and its progression [

9], v) CD4 T-lymphocytes <200 per mm3 [

3] and vi) previous infections [

4,

6,

10,

11,

12]. A history of repeated blood transfusions [

13], the use of corticosteroids [

14], intensive chemotherapy regimens with radiotherapy [

15], and the use of new therapeutic strategies, such as biologic agents [

16,

17,

18], increase the risk of IA in patients with HM.

Given the high morbidity and mortality of IA in patients with HM, good prevention strategies are essential to prevent this serious disease. Prevention measures can be stratified into four levels: i) hospital environmental prevention, ii) nosocomial infection control, iii) prophylaxis, and iv) out-of-hospital environmental prevention. Antifungal prophylaxis is strongly recommended for high-risk patients to prevent IA [

19,

20,

21]. According to the latest consensus document developed by European societies, the main antifungal drugs recommended depending on the risk of the patient are: posaconazole, liposomal amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole [

21,

22].

Prevention of nosocomial infection is achieved thanks to adequate training of the healthcare personnel responsible for high-risk IFI patients and therefore the use of scores, such as EQUAL 2018, which allow reporting on the quality of clinical care provided [

22]. In addition, all this is aided by the creation of IFI incidence records, which allow the detection of increases in IFI incidence, to act accordingly in the event of outbreaks by performing cultures, verifying facilities, and correcting deficiencies found [

23].

Environmental risk factors are related to an increase in the number of conidia per cubic meter [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

24]. These can be produced naturally by seasonal changes or exposure to plant products, or artificially produced due to the proximity of construction areas, including in the hospital itself, or due to the lack of adequate insulation in the rooms of patients with HM, such as: i) inadequate insulation of doors and windows, ii) lack of High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters, iii) no laminar air flow (LAF), iv) no positive differential pressure, and v) low number of air renewals.

High-risk patients with HM should be housed in hospital rooms with a protected environment, which are characterized by the presence of protected air. This protected air is achieved through the following: i) the presence of HEPA filters; ii) implementation of mobile air decontamination systems; iii) independent zones from the rest of the hospital; and iv) construction materials that do not release particles [

23,

25].

Antifungal prophylaxis and infection control measures are the most widely implemented with wide consensus in the prevention of IA [

26]. However, there is a lack of consensus on the level of airborne conidia that should be considered normal in different environments, which makes it difficult to establish clear guidelines for reducing exposure. Furthermore, the impact of environmental measures on the prevention of invasive aspergillosis is difficult to measure due to the complexity of the disease and the factors that contribute to its development [

27].

The purpose of this research is to identify the recent risk factors and environmental control measures that fight against the development of invasive fungal aspergillus infection in patients with acute hematologic malignancies (AML) to establish preventive actions for reducing the incidence of invasive aspergillosis at hospitals.

2. Materials and Methods

PICO Question

Our research question was: "What are the environmental control measure more effective measure to avoid the development of invasive fungal aspergillus infections?" This was transformed into the following PICO question.

P: Patients with acute hematologic neoplasms, (HN) acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/recipients of hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation

I: Environmental Control measures

C: not apply

O: Invasive aspergillosis

Study Selection

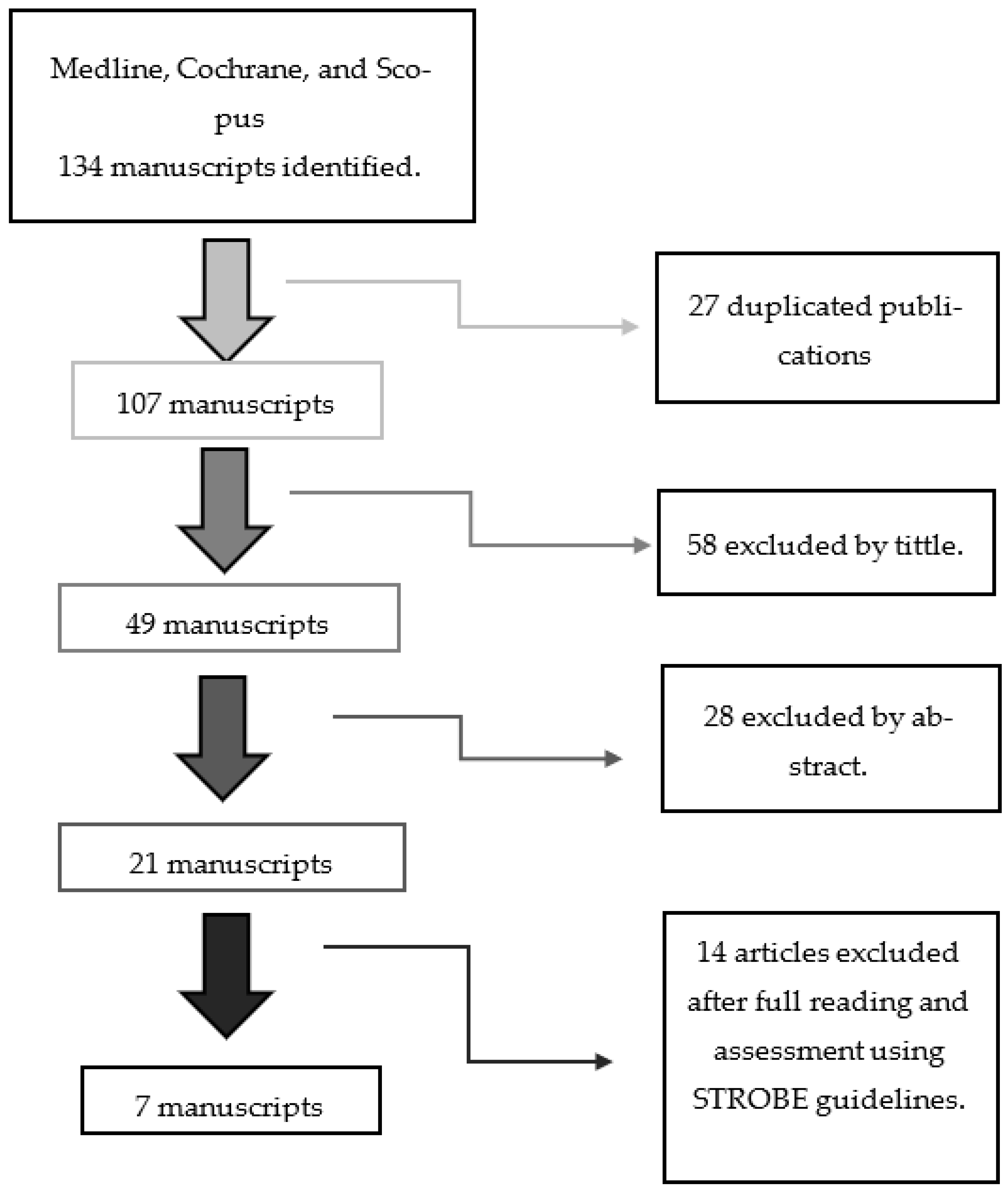

The review of the retrieved papers went through a five-stage process. Initially, the articles were searched, followed by the elimination of duplicates. The next steps involved assessing the titles and abstracts of the potentially relevant papers identified. Subsequently, the full texts of the selected articles were thoroughly examined, and their quality was evaluated. Throughout all stages, two independent group of reviewers (D.R.P., E.G.C) and (J.R.P and F.M.M) conducted the review, with a third group of independent reviewers (J.C.C.V and A.V.A.) involved in cases where there was disagreement.

Inclusion Criteria

Scientific articles from the years 2009-2023.

Articles published in Spanish and English.

Types of studies: Experimental studies, observational studies

Articles containing the key descriptors: "Aspergillosis", "Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis", "Hematologic neoplasms", "Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation", "Leukemia", "Risk factors" and "Prevention".

Exclusion Criteria

- 5.

Articles that after applying the STROBE guidelines, for observational studies, respectively did not reach a minimal punctuation.

- 6.

Articles that do not address our research question.

- 7.

Articles in pediatric populations

Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted by two reviewers who worked independently and followed Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and PRISMA guidelines [

28]. Information from each included study was extracted and documented. The extracted data encompassed various aspects, including the year of publication, country, study design, quality assessment, sample size, target population, description of interventions, outcome measures, and study results.

Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality was assessed using STROBE statement for observational studies [

29]. All studies with 50% or less checked items were excluded for review. In all cases, the evaluation was conducted by two independent reviewers.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The data obtained from all the studies that met the inclusion criteria were organized and presented in tabular form. The tables include information about the study authors, sample characteristics, measurement of outcome variables, and key results. A qualitative synthesis was conducted, incorporating all the identified studies, and the findings are presented in the tables.

3. Results and Discussion

The research methodology went through a five-stage process. The article-selection process is detailed in

Scheme 1. We selected Medline, Cochrane and Scopus databases for our search. The search strategy is detailed in

Table 1. Initially, 134 articles were identified by the three databases. We eliminated 27 duplicated publications.

We obtained findings from seven studies in our research. Four of them are based on the environmental control measures established at hospitals during building construction [

30,

31,

32,

33]. High-efficiency particulate air filtration (HEPA) and laminar air flow (LAW) are the main environmental control measures mentioned, presented in four out of seven studies of the search [

30,

31,

33,

34]. It should be highlighted research that study a new mobile air decontamination system called Plasmair® [

35]. All of them are evaluated at hospitals [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] and one include air analysis at home [

36]. Two studies included antifungal prophylaxis as a preventive measure for IA [

30,

33]. Their main features are detailed in

Table 2.

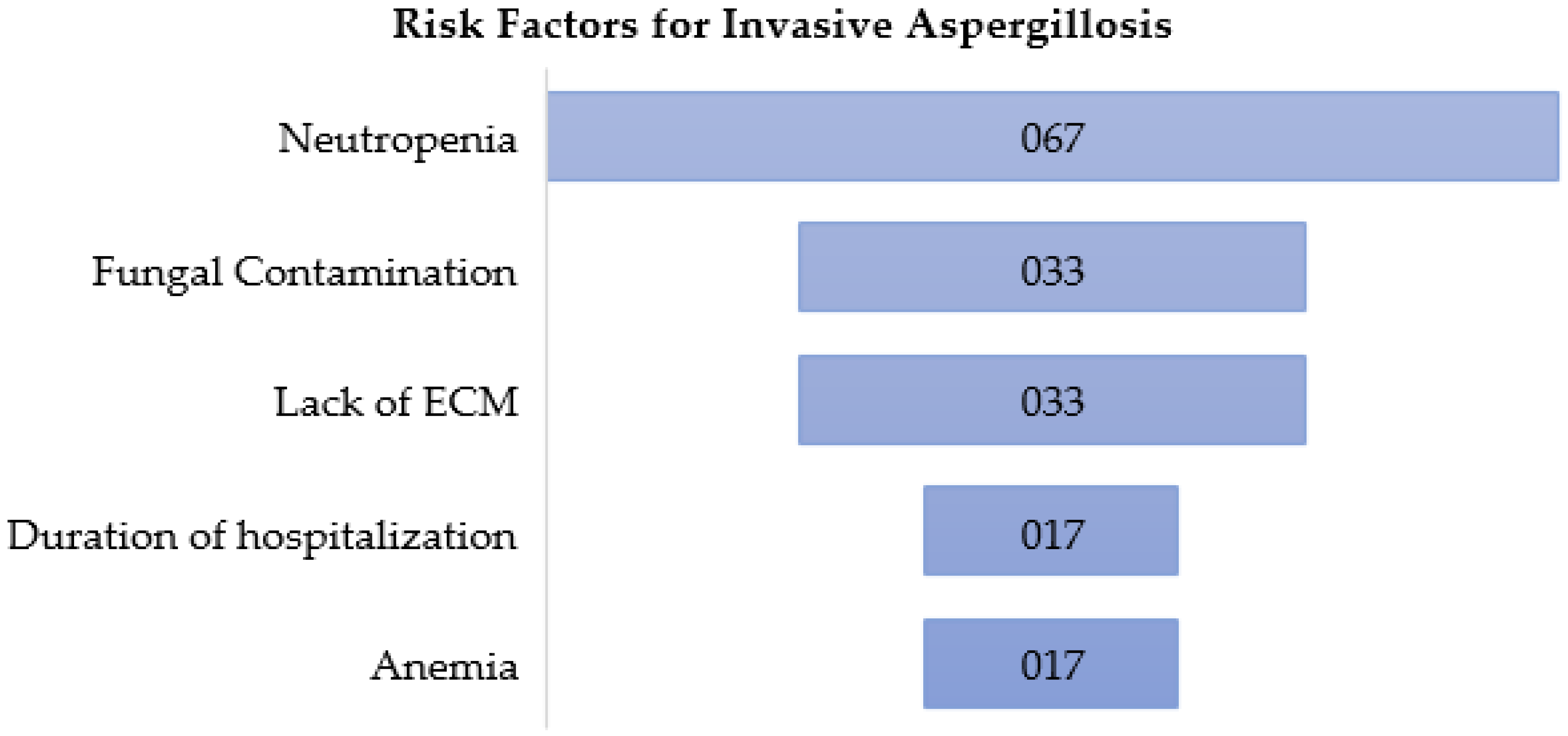

3.1. Risk Factors for IA

The risk factors for IA detected in this research are summarized in

Figure 1. Neutropenia was evaluated as a risk factor in four of the seven studies of this research [

30,

32,

34,

36]. The incidence of IA was higher when the duration of neutropenia was longer than 7 days (Odds Ratio (OR): 9.95 (95% CI: 2.86-34.94) [

30]. A third of patients that experienced neutropenia for more than 40 days developed IA [

34]. IA occurred in 10 patients with severe neutropenia of the 14 patients with IA in Rocchi et al. study [

36]. Neutropenia was strongly correlated with IA in Loschi et al. study [

32]. These results confirm the overwhelming role of neutropenia in IA, as other previous studies and reviews showed [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Fungal contamination under 0.1 CFU/m3 in a HEPA-filtered area or under 5CDF/m3 in an isolation area is enough to trigger IA in hospital patients [

41]. Two of the researches of this review established the presence of fungal contamination as predictor variables for the development of IA [

33,

36]. In Rocchi et al. study, 5 patients of 14 that developed IA were concomitant with abnormally high levels of

A. fumigatus in hematology ICU corridors (14-25 CFU/m3, [

36]). In the same study, another 5 of the 14 patients with IA, although there was no fungal contamination during hospitalization, they were exposed to A. fumigatus and A. flavus at their homes (9-48%, [

36]). So, there is a risk of developing IA in patients with HM when there is a significant exposure to

A. fumigatus and

A. flavus at hospital or even at homes [

36]. Park et al. demonstrated that the total incidence rate of IA was significantly higher during demolition and excavation works at hospital than during construction, when airborne fungal contamination was lower (9.95 vs. 5.60 CFU/m3 for total mold spores and 2.35 vs. 1.70 CFU/m3 for

Aspergillus spp) [

33]. Herein, differences in spore levels are more pronounced for total mold spores than for

Aspergillus spp. Therefore, total mold spore levels could be a predictor of ineffective air filtration and/or the existence of conditions that favor the settling of molds, as well as an indirect marker of air fungal contamination [

33]. Previous studies confirm that patients with hematologic malignances are at higher risk of IA caused by molds, being

Aspergillus spp. the most common pathogen [

42], as well as corroborate a significant relationship between environmental fungal contamination in hematology wards and IA incidence [

43].

Construction activity at hospitals has been reported to be an independent risk factor for invasive fungal disease in several studies [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Two of our studies highlighted the lack of environmental control measures and/or the lack of maintenance of these measures as a significant risk factor for IA in patients with HM during building construction or renovation at hospitals [

30,

31]. In Combariza et al. study, the absence of environmental control measures is an independent risk factor for IA (OR: 2.99 (95% CI: 1.20-7.41) [

30]. After long-term use of LAF systems in the hospital of Iwasaki et al. study, the risk of aspergillosis was increased (Hazard Ratio (HR): 5.65). These results suggest that more efforts should be made for establishing proper environmental control measures, as well as adequate filtration system maintenance protocols [

31].

Other risk factors for IA in patients with HM are also mentioned in some of the studies of our research. The duration of hospitalization is one of them, that were strongly correlated with IA in Loschi et al. study [

32]. The other one is anemia, having a positive correlation with IA in Friese et al. study (OR: 1.044 (95% CI: 1.008-1.081) [

34]. We could highlight that, to our knowledge, it is the first time that this association is reported in literature.

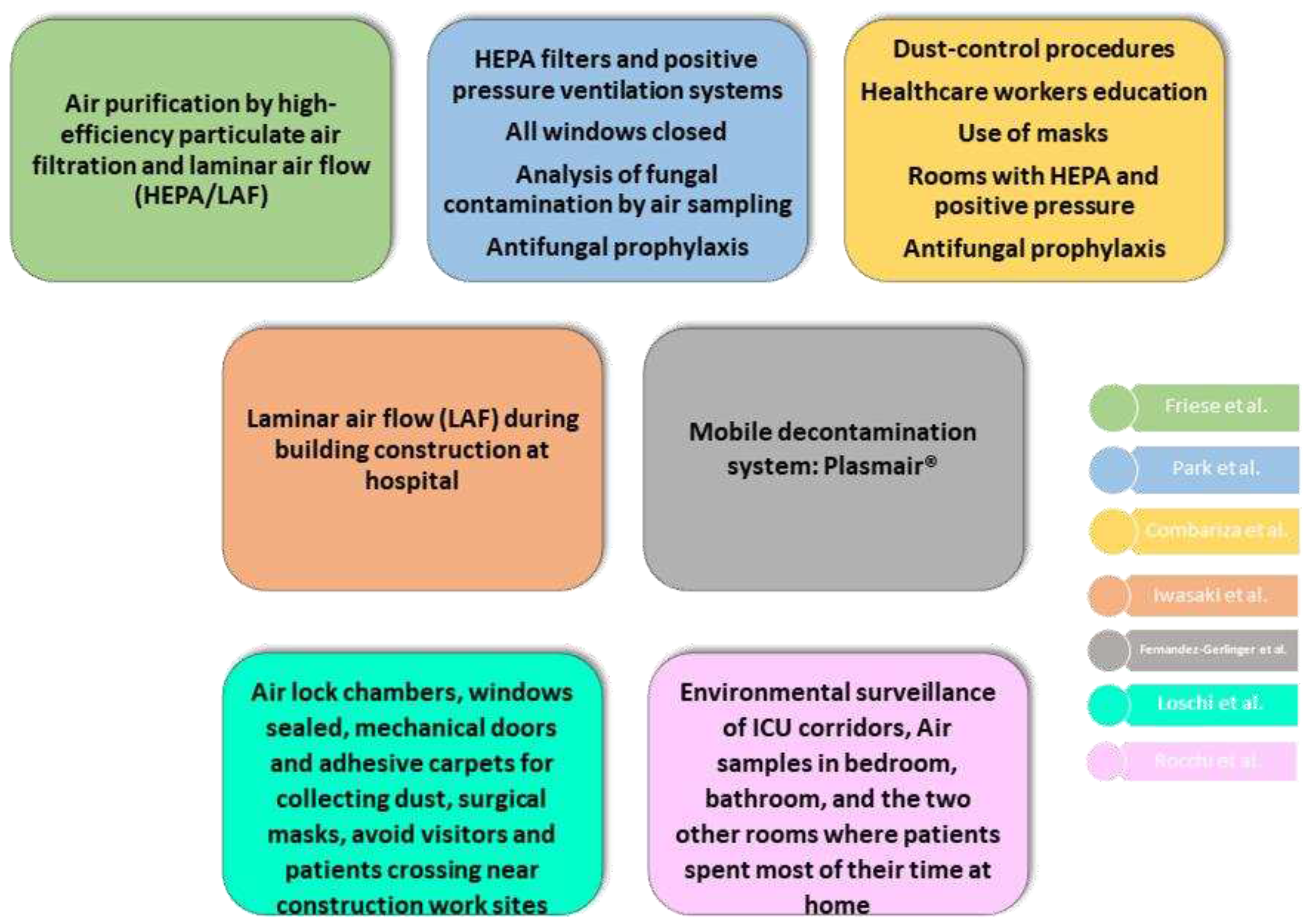

3.2. Environmental Preventive Measures against IA

All our studies implemented some kind of environmental control measures in their research that are detailed in

Figure 2.

The absence of proper environmental prevention measures increased the incidence of invasive aspergillosis (IA) in patients with HM during hospital building renovation/construction [

34,

36]. Proper pre-planning before construction/renovation work is essential to establish optimal prevention guidelines based on the needs of at-risk population. Adequate training for healthcare personnel is highlighted in this planning. These measures must be more restricted during the phases of excavation/demolition [

38].

Three studies [Combariza, Park, Loschi] emphasized the effectiveness of physical barriers during hospital construction/remodeling for avoiding IA infection. With Combariza et al.´s environmental control measures (

Table 2), the incidence of IA was reduced from 25.8% to 12.4%. These environmental control measures were protective for IA with a relative risk of 0.595 (95% CI: 0.39-0.90) [combariza]. The incidence of IA was higher in the ward without any ventilation system and with the highest total mold and Aspergillus spp in Park et al. study (ref,

Table 2). Moreover, they highlight that the incidence of IA was higher in the period of demolition and excavation, when airborne fungal spore levels tended to be higher (Park). Environmental control measures established by Loschi et al. (

Table 2) were enough to prevent invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with neutropenia (Loschi).

In hospital building renovations, air filtration is a proven protective factor against IA (Loschi). Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention guidelines recommends HEPA filter systems for high-risk patients to reduce IA at hospitals during construction and renovation. In Combariza et al. study, the most effective measure to prevent IA was the isolation of patients with HM in HEPA-filtered rooms (RR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.84-0.94) [combariza]. Fungal contamination was lower in the wards equipped with HEPA filters in Park et al. study (Park), allowing the reduction of IA in these wards of the hospital. Another effective procedure to avoid aspergillosis is LAF isolation. Iwasaki et al. demonstrated that LAF system reduce the risk of aspergillosis during the construction of a new hospital (HR: 1.97), although it was increased when they were installed in a new hematology ward (HR: 5.65) (Iwasaki).

HEPA and LAF systems are suitable methods to reduce the concentration of airborne fungal spores. In a study carried out in non-transplant patients with HM, the implementation of HEPA/LAF was associated with a > 50 % risk reduction of neutropenia-related IA (Friese). IA was significantly less frequent under HEPA/LAF than under ambient conditions (OR: 0.097; 95% CI: 0.010-0.923). Its reduction was also observed in patients with a fatal hospitalization outcome (OR: 0.077). In 2010, in a large acute tertiary-care hospital in Singapore, researchers demonstrated that portable HEPA filters were effective in the prevention of IA (OR: 0.49 (95% CI: 0.28-0.85) (Abdul Salam del TFM). A study carried out in immunocompromised patients also demonstrated the efficiently prevention measure of HEPA with or without LAF against IA (Herbrecht de Fatima). Therefore, we could confirm that high-risk patients with HM should be isolated in hospital areas with HEPA/LAF systems to avoid IA. However, the availability of such systems in hospital areas is limited. For that, portable environmental decontamination equipment has emerged, allowing the administration of high-quality air according to the needs of high-risk patients with HM. Fernandez-Gerlinger et al. [

33] demonstrated that a mobile air decontaminated system called Plasmair® reduced the incidence of IA in these patients (OR: 0.11; 95% CI: 0.00-0.84).

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommended antifungal prophylaxis for the management of aspergillosis in 2016 (Patterson del TFG). However, this prophylaxis did not influence in IA incidence significantly in our study. The combined administration of antifungal agents and properly applied environmental prevention measures are not better than the isolated application of environmental prevention measures in terms of reducing the risk of IA, as reported by Combariza et al. [

34]. These results are also observed by Friese et al. [

35]. Previous studies, as one carried out in 2001, corroborate these results. Oren et al. [

40] compared environmental control measures with antifungal prophylaxis against IA in acute leukemia patients, demonstrating that HEPA reached the absence of new cases of IA in patients hospitalized in rooms with this filtration system, while there was a partial reduction in IA incidence (from 50% to 43%) achieved with antifungal prophylaxis. Moreover, ISDA recognized that although there is an optimal antifungal therapy against IA, the mortality rate of the disease remains high (Patterson del TFG). Therefore, although antifungal prophylaxis is a priority measure for high-risk patients, it could not be considered a substitute for the proper implementation of mechanical prevention measures.

3.3. Main Recommendations to Fight against IA

We also collected the main proposals given by the researchers based on their studies to fight against IA in patients with HM (

Figure 3).

The priority for most of the studies reviewed (6 of 7) is to establish proper environmental control measures against IA (Friese, Iwasaki, combariza, Fernandez, loschi, rocchi). Combariza et al. concluded their study with the effectiveness of the implementation of environmental control measures during hospital construction activity for preventing IA in acute leukemia patients (Combariza), as well as Loschi et al. (loschi). Rocchi et al. supports that these preventive measures should be also achieved in patients´ homes. For that, they suggested giving advice such as: avoiding activity in highly contaminated rooms (garage, for example), cleaning all rooms, or even installing air treatment devices (rocchi). However, previous studies found difficulties to control patient´s environment at home (Herbrecht de Fatima), suggesting more studies in this sense to accomplish this issue.

HEPA, LAF and Plasmair® systems are well established as efficient protective factors against IA (friese, iwasaki y fernandez). As these systems are quite expensive and not available to all patients, all researchers agreed in leaving this service to the most compromised patients that could be immunocompromised patients (iwasaki) with episodes of neutropenia for 10 days or more (friese). The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infection Diseases (ESCMID) gave some recommendations in 2016 about how to deal with IA in patients with HM, suggesting that these patients should be segregated into subgroups and provided specific grading for each of them, including environmental measures in the prevention (Tissot del TFM). Loschi et al. suggest that a multidisciplinary committee should make the decision about who could be beneficiary of the different mechanical preventive measures, as the CDC recommends (Loschi). It should be highlighted the risk stratification for IFI made by Pagano et al. (pagano 2017 del TFM) in their review, offering it as a useful tool for optimizing the diagnostic procedures and therapeutic strategies for preventing and treating IFIs in patients with hematological malignances.

The monitoring of airborne fungal spore levels is recommended during construction periods in hospitals with immunocompromised patients by Park et al. (park), as well as by Rocchi et al. (rocchi). These last researchers also recommend the assessment on patients´homes, with an environmental survey and monitoring levels, focusing on A. fumigatus and A. flavus (rocchi). Previous studies also underline the importance of environmental surveillance for the application of strict preventive measures against IA (Alberti del TFM). Iwasaki et al. also add fungal prophylaxis in patients who are highly exposed to environmental factors (iwasaki). Diaz Arevalo and Kalkum suggest new antifungal vaccines as future prophylaxis treatment, reducing the sensitivity to IA in high-risk patients (Diaz Arevalo del TFM). Ruiz Camps (ref) point out, in an editorial letter, that there are no studies addressing the definition of the optimal duration of antifungal therapy, evoking us to think how to manage it soon, when we will need to decide which patients at risk should receive prophylaxis, for how long and with which drug. Other recommendations included the delay of hospital release when needed, as well as introducing health monitoring before patients return home if there is a suspicion of high-risk IA (rocchi).

3.4. Strengths and Weakness

This research synthetizes and point out the main risk factors related to IA in patients with HM mentioned in the recent scientific literature. We also highlight the environmental preventive measures considering by several researchers in hospitals, in building construction or not, and at homes with patients with HM against IA. In addition, we emphasize the main recommendations made to fight against IA in these patients worldwide.

Publication and selection biases are the main limitations of this study. We established clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to reduce these biases, with the greatest possible objectivity, to prevent the results from being distorted. Language and year of publication could be another bias, as we include studies from the last 10 years (2013-2023) written in Spanish or English. Other aspects that could compromise the validity of the results obtained in this research are the quality of the original studies included, the variability between studies, or errors in the analysis phase. The conclusions of the research are largely dependent on these aspects. Two of us analyzed each study with Prisma and Strobe guidelines (ref de ambas) to minimize this last bias.

Furthermore, the studies differ in sample sizes, study populations, and methodologies, introducing potential variations in the reported incidence rates. Certain studies have limitations, such as being conducted in a single center or not measuring specific variables, which can influence the accuracy and generalizability of the findings. Therefore, it is important to compare IA incidence rates with caution in these studies.

4. Conclusions

We identified the recent risk factors for IA associated with patients with IA. Neutropenia is the main risk factor, followed by fungal contamination at hospitals and patients´ homes, and lack of proper environmental control measures. Duration of hospitalization and anemia are also mentioned as risk factors in our research. We also demonstrated the effectiveness of physical barriers during hospital construction/remodeling for avoiding IA in patients with HM. HEPA, LAF and Plasmair® systems are suitable methods to reduce the concentration of airborne fungal spores. Antiphungal prophylaxis did not influence significantly in the reduction of IA in our study. Although IDSA recommend it, we suggest not considering this prophylaxis as a substitute of physical barriers, but an additional treatment for high-risk patients. To stablish proper environmental control measures against IA is the prior recommendation in most of the studies researched. These mechanical preventive measures should go with professional education of health workers and multidisciplinary committees that adapt these measures according to a risk stratification of patients. Antifungal prophylaxis should be complementary to environmental control measures and never substituted by these last ones. Environmental surveillance is also recommended not only at hospitals, even at homes, where fungal contamination is a risk factor for IA. Studies evaluating the efficiency of environmental control measures against IA at patients´ homes should be addressed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.A. and J.C.C.V; methodology, A.V.A and EGC.; formal analysis, D.R.P and J.C.C.V; investigation, D.R.P, J.R.P, F.M, E.G:C, ; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.; writing—review and editing, A.V.A., D.R.P , J.R.P and E.G.C.; supervision, A.V.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research not received external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pemán, J.; Salavert, M. Epidemiología y Prevención de Las Infecciones Nosocomiales Causadas Por Especies de Hongos Filamentosos y Levaduras. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2013, 31, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neofytos, D.; Horn, D.; Anaissie, E.; Steinbach, W.; Olyaei, A.; Fishman, J.; Pfaller, M.; Chang, C.; Webster, K.; Marr, K. Epidemiology and Outcome of Invasive Fungal Infection in Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: Analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance Registry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemán, J.; Salavert, M. Epidemiología General de La Enfermedad Fúngica Invasora. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Carratalà, J. Patogenia de La Infección Fúngica Invasora. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, C.; Vázquez, L. Invasive Aspergillosis in the Patient with Oncohematologic Disease. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2018, 35, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, V.; Jhingran, A.; Dutta, O.; Kasahara, S.; Donnelly, R.; Du, P.; Rosenfeld, J.; Leiner, I.; Chen, C.-C.; Ron, Y.; et al. Inflammatory Monocytes Orchestrate Innate Antifungal Immunity in the Lung. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crokaert, F.; Walsh, T.J.; Fiere, D.; Selleslag, D.; Maertens, J.; Edwards, J.E.; Bennett, J.E.; Denning, D.W.; Rex, J.H.; Stevens, D.A.; et al. Defining Opportunistic Invasive Fungal Infections in Immunocompromised Patients with Cancer and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants: An International Consensus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, M.; Caocci, G.; Ledda, A.; Orrù, F.; Fozza, C.; Deias, P.; Tidore, G.; Dore, F.; La Nasa, G. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency and Risk of Invasive Fungal Disease in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 2558–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo Llamas, J.C.; Ruiz-Camps, I. Infección Fúngica Invasora En Los Pacientes Hematológicos. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Chamilos, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Giralt, S.; Cortes, J.; Raad, I.I.; Manning, J.T.; Han, X. Increased Bone Marrow Iron Stores Is an Independent Risk Factor for Invasive Aspergillosis in Patients with High-Risk Hematologic Malignancies and Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancer 2007, 110, 1303–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Barba, P.; Arnan, M.; Moreno, A.; Ruiz-Camps, I.; Gudiol, C.; Ayats, J.; Orti, G.; Carratala, J. Invasive Aspergillosis Complicating Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Severely Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, e16–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmal, S.; Mahmood, M.; Abu Saleh, O.; Larson, J.; Sohail, M.R. Invasive Fungal Infections Associated with Prior Respiratory Viral Infections in Immunocompromised Hosts. Infection 2018, 46, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, B.; Azap, A.; Akan, H.; Yılmaz, G.; Elhan, A. D-Index: A New Scoring System in Febrile Neutropenic Patients for Predicting Invasive Fungal Infections. Turkish J. Hematol. 2016, 33, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Giovannini, G.; Pierini, A.; Bell, A.S.; Sorci, G.; Riuzzi, F.; Donato, R.; Rodrigues, F.; Velardi, A.; Aversa, F.; et al. Genetically-Determined Hyperfunction of the S100B/RAGE Axis Is a Risk Factor for Aspergillosis in Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Camps, I. Aspergillosis: Beyond the Oncohematological Patient | Aspergilosis: Más Allá Del Paciente Oncohematológico. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Camps, I.; Jarque, I. Enfermedad Fúngica Invasora Por Hongos Filamentosos En Pacientes Hematológicos. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2014, 31, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghez, D.; Calleja, A.; Protin, C.; Baron, M.; Ledoux, M.P.; Damaj, G.; Dupont, M.; Dreyfus, B.; Ferrant, E.; Herbaux, C.; et al. Early-Onset Invasive Aspergillosis and Other Fungal Infections in Patients Treated with Ibrutinib. Blood 2018, 131, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedel, W.L.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Pasqualotto, A.C. Aspergillosis in Patients Treated with Monoclonal Antibodies. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2009, 26, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A.; Rhodes, J.L.; Fisher, M.C.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical Implications of Globally Emerging Azole Resistance in Aspergillus Fumigatus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2016, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornely, O.A.; Koehler, P.; Arenz, D.C.; Mellinghoff, S. EQUAL Aspergillosis Score 2018: An ECMM Score Derived from Current Guidelines to Measure QUALity of the Clinical Management of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Mycoses 2018, 61, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissot, F.; Agrawal, S.; Pagano, L.; Petrikkos, G.; Groll, A.H.; Skiada, A.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Calandra, T.; Viscoli, C.; Herbrecht, R. ECIL-6 Guidelines for the Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis, Aspergillosis and Mucormycosis in Leukemia and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Haematologica 2017, 102, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Riesgo, H.; De Trabajo, G.; Ramos Cuadra, A. RECOMENDACIONES PARA LA MONITORIZACIÓN DE LA CALIDAD MICROBIOLOGICA DEL AIRE (BIOSEGURIDAD AMBIENTAL) EN ZONAS .

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Aguilar-Guisado, M.; Carratalà, J.; Castro, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, M.; María Aguado, J.; María Fernández, J.; Fortún, J.; Garnacho-Montero, J. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Invasive Diseases Caused by Aspergillus: 2018 Update by the GEMICOMED-SEIMC/REIPI Documento de Consenso Del GEMICOMED Perteneciente a La Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínic .

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Park, B.J.; Alexander, B.D.; Anaissie, E.J.; Walsh, T.J.; Ito, J.; Andes, D.R.; Baddley, J.W.; Brown, J.M.; et al. Prospective Surveillance for Invasive Fungal Infections in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients, 2001–2006: Overview of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Database. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Camps, I.; Aguado, J.M.; Almirante, B.; Bouza, E.; Ferrer Barbera, C.; Len, O.; López-Cerero, L.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J.L.; Ruiz, M.; Solé, A.; et al. Recomendaciones Sobre La Prevención de La Infección Fúngica Invasora Por Hongos Filamentosos de La Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC). Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2010, 28, e1–e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peláez, T.; Muñoz, P.; Guinea, J.; Valerio, M.; Giannella, M.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Bouza, E. Outbreak of Invasive Aspergillosis after Major Heart Surgery Caused by Spores in the Air of the Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonberg, R.-P.; Gastmeier, P. Nosocomial Aspergillosis in Outbreak Settings. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 63, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risk of Bias Tools - Current Version of RoB 2 Available online:. Available online: https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, 1628–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combariza, J.F.; Toro, L.F.; Orozco, J.J. Effectiveness of Environmental Control Measures to Decrease the Risk of Invasive Aspergillosis in Acute Leukaemia Patients during Hospital Building Work. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 96, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, M.; Kanda, J.; Hishizawa, M.; Kitano, T.; Kondo, T.; Yamashita, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A. Effect of Laminar Air Flow and Building Construction on Aspergillosis in Acute Leukemia Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschi, M.; Thill, C.; Gray, C.; David, M.; Bagatha, M.-F.; Chamseddine, A.; Contentin, N.; Jardin, F.; Lanic, H.; Lemasle, E.; et al. Invasive Aspergillosis in Neutropenic Patients During Hospital Renovation: Effectiveness of Mechanical Preventive Measures in a Prospective Cohort of 438 Patients. Mycopathologia 2015, 179, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Ryu, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kwak, S.H.; Jung, J.; Lee, J.; Sung, H.; Kim, S.H. Airborne Fungal Spores and Invasive Aspergillosis in Hematologic Units in a Tertiary Hospital during Construction: A Prospective Cohort Study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friese, C.; Breuckmann, K.; Hüttmann, A.; Eisele, L.; Dührsen, U. Neutropenia-Related Aspergillosis in Non-Transplant Haematological Patients Hospitalised under Ambient Air versus Purified Air Conditions. Mycoses 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Gerlinger, M.-P.; Jannot, A.-S.; Rigaudeau, S.; Lambert, J.; Eloy, O.; Mignon, F.; Farhat, H.; Castaigne, S.; Merrer, J.; Rousselot, P. The Plasmair Decontamination System Is Protective Against Invasive Aspergillosis in Neutropenic Patients. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, S.; Reboux, G.; Larosa, F.; Scherer, E.; Daguindeau, E.; Berceanu, A.; Deconinck, E.; Millon, L.; Bellanger, A.-P. Evaluation of Invasive Aspergillosis Risk of Immunocompromised Patients Alternatively Hospitalized in Hematology Intensive Care Unit and at Home. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, L.; Busca, A.; Candoni, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Cesaro, S.; Fanci, R.; Nadali, G.; Potenza, L.; Russo, D.; Tumbarello, M.; et al. Risk Stratification for Invasive Fungal Infections in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: SEIFEM Recommendations. Blood Rev. 2017, 31, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, L.; Akova, M.; Dimopoulos, G.; Herbrecht, R.; Drgona, L.; Blijlevens, N. Risk Assessment and Prognostic Factors for Mould-Related Diseases in Immunocompromised Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, L.; Caira, M.; Candoni, A.; Offidani, M.; Martino, B.; Specchia, G.; Pastore, D.; Stanzani, M.; Cattaneo, C.; Fanci, R.; et al. Invasive Aspergillosis in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A SEIFEM-2008 Registry Study. Haematologica 2010, 95, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, M.Y.; Chou, C.H.; Lin, C.C.; Bai, L.Y.; Chiu, C.F.; Yeh, S.P.; Ho, M.W. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Invasive Fungal Infections during Induction Chemotherapy for Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warris, A.; Onken, A.; Gaustad, P.; Janssen, W.; van der Lee, H.; Verweij, P.E.; Abrahamsen, T.G. Point-of-Use Filtration Method for the Prevention of Fungal Contamination of Hospital Water. J. Hosp. Infect. 2010, 76, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, L.; Caira, M.; Candoni, A.; Offidani, M.; Fianchi, L.; Martino, B.; Pastore, D.; Picardi, M.; Bonini, A.; Chierichini, A.; et al. The Epidemiology of Fungal Infections in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: The SEIFEM-2004 Study. Haematologica 2006, 91, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alberti, C.; Bouakline, A.; Ribaud, P.; Lacroix, C.; Rousselot, P.; Leblanc, T.; Derouin, F. Relationship between Environmental Fungal Contamination and the Incidence of Invasive Aspergillosis in Haematology Patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 2001, 48, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruszkewycz, V.; Ruben, B.; Hypes, C.M.; Bostic, G.D.; Staszkiewicz, J.; Band, J.D. A Cluster of Pseudofungemia Associated with Hospital Renovation Adjacent to the Microbiology Laboratory. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1992, 13, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aisner, J.; Schimpff, S.C.; Bennett, J.E.; Young, V.M.; Wiernik, P.H. Aspergillus Infections in Cancer Patients: Association With Fireproofing Materials in a New Hospital. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1976, 235, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan Kew Lai A Cluster of Invasive Aspergillosis in a Bone Marrow Transplant Unit Related to Construction and the Utility of Air Sampling. Am. J. Infect. Control 2001, 29, 333–337. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, P.M.; Williams, B.G.; Hetherington, S. V.; Williams, B.F.; Giannini, M.A.; Pearson, T.A. Aspergillus Terreus During Hospital Renovation. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1993, 14, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weems, J.J.; Davis, B.J.; Tablan, O.C.; Kaufman, L.; Martone, W.J. Construction Activity: An Independent Risk Factor for Invasive Aspergillosis and Zygomycosis in Patients with Hematologic Malignancy. Infect. Control 1987, 8, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).