1. Introduction and Paper Structure

Organic Growth Theory was first introduced for corporates in [

1], where numerous engagement and inputs were received from different stakeholders in sustainability community around the world. The concept was first officially published open-source and contributed to the development of sustainable businesses.

The purpose of OGT (Organic Growth Theory) research is to define an incremental approach to grow and generate revenue without compromise the capacity of forthcoming generations to satisfy their needs [

2] [

3] [

4]. The theory was further tailored focusing on corporate world. In this paper, the focus is on countries and the global economy. This article is organized as follows:

The background and a theoretical/scientific justification for OGT is described in

Section 2.

Section 3 is assigned to literature review and data collection approach.

In section 4, more information about the Organic Growth Theory is presented.

The adaptation of Organic Growth Theory for Global Sustainable Competitiveness is presented in section 5.

Results and future research direction are presented in section 6.

2. Background

As announced by United Nations alongside world leaders on the 1

st of January 2016, Sustainable Development goals construct a vision and pathway for a global, sustainable future. The 17 goals point to an ambitious agenda for humanity by aiming to eradicate hunger, and poverty for all human beings, create efficient and sustainable industrial structures and neutralize the effects of climate change and maintain a habitable and healthy planet [

5]. 2030 UN Agenda identifies “leaving no one behind” as a core value and demands each country to take action and collaborate towards a collective transformation of human civilization. Therefore, no matter their scale and developmental stage, all countries should join their efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals accurately and on time.

In alignment with this direction, corporations worldwide are now also upgrading their definitions of value by incorporating sustainability into their decision-making processes [

6] [

7]. Top management and governmental support are among the most important factors that enable the transformation of industries towards a sustainable and circular direction [

8]. Governmental organizations can facilitate the transformation towards sustainability by providing incentives and funds for industrial organizations by assisting the change and creating a collaborative atmosphere [

9].

Quantifying sustainability is a vital step toward sustainability transformations since it enables sustainability measurement and the setting of specific targets [

6]. The most appropriate indicators and indices for the assessment of sustainability in many domains have been investigated and modeled since what can’t be measured, cannot be managed and improved [

10]. Decision-makers and policymakers can use sustainability assessment as a tool to determine what measures to take or not take in an effort to make civilization more sustainable [

11].

Therefore, sustainability performance measurement has become an active research field with noticeable contributions from various scholars [

12]. By measuring the sustainability performance of countries, it will be possible to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each country, track their performance levels in time, benchmark with other countries and guide their policy making process [

13] [

14] [

15].

3. Literature Review and Data Collection Approach

Sustainability measurement is a vital but challenging task. One of the main challenges of sustainability measurement in the country level is the uncertainty in data which may arise from ambiguous or incomplete information, data series uncertainties or uncertainty about the future [

16]. Therefore, in order to fully represent the true nature of the problem, models used in sustainability assessment should capture the multiple qualitative, quantitative and uncertain characteristics of the parameters [

11].

The first set of indices were proposed by United Nations in 1995, under the name Human Development Index (HDI). The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) and Ecological Footprint (EF) are also among the most widely recognized performance indicators. Among the methodologies used for sustainability performance assessment, one can list multi-criteria decision analysis methods, Data Envelopment analysis (DEA), Life Cycle analysis (LCA), comprehensive evaluation, system dynamics and Fuzzy-set theory [

11], [

16].

Despite the efforts by the researchers and UN, the term sustainability is still vague and difficult to quantify [

17] [

18]. Moreover, different conceptualization of sustainability and quantification methods lead to different even controversial results [

10], [

16], [

19].

Sustainability performance measurement in the macro level (city, country) can be thought of as a classic Multiple Criteria Decision Aiding (MCDA) [

20] problem due to sustainability being assessed by a number of indicators [

19] [

21]. Since the start of 21

st century, numerous intergovernmental plans and private programs have been executed to encourage global sustainable development across the world. These include New Urban Agenda by UN-Habitat (2016), Sustainable Development Goals by United Nations (2016), and Istanbul Declaration by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (2004) and the HK2030 Study by Hong Kong Planning Department (2007). OECD has delivered multiple directions and tactics to evaluate sustainable development (OECD, 2010; OECD, 2020; OECD, 2021) [

22].

Index studies are at the core of attention to ensure sustainable development to be truly executed. To give few examples, Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Index [

23] [

24], The Global Innovation Index [

25], Environmental Performance Index [

26], Genuine Progress Indicator [

26], Sustainable Society Index [

27], Legatum Prosperity Index [

28], are among indices which published by different organizations today assist maintaining the concept of sustainability alive while addressing and measuring multiple dimensions of sustainable development [

29]. To attain sustainable and permanent development, CE (Circular Economy) is a requirement since it improves resource efficiency and eliminates material dependability [

22].

Generating energy in sustainable manner has come with three requirements to be part of sustainable development [

30] [

31] [

32] [

33]:

The source of energy is not significantly exhausted by continuous use.

Generation of emission of pollutants or other hazards to human or ecological and climate systems is not significant.

Perpetuation of significant social injustices is not compromised.

Prior to 2005 [

6], Chinese economic growth was not sustainable, owing to environmental problems and large income gaps. Since then, however, there has been a change after the Chinese government announced some goals for sustainable development in its 11th five-year plan (2006–2010); the plan included proposals for environmental pollution regulations and reducing the social income gap [

34]. It seems that the Chinese government’s policies for sustainability were effective in in- creasing the sustainability performance of the country. China emphasized more on economic performance than environmental and social performance. Social performance, representing economic equality, has the lowest value, suggesting that the country’s inefficiency of sustainability is mainly because of social inefficiency.

In [

35], a calculation and comparison method of sustainability performances of European countries is presented. Top four European countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Austria) have superior indexes of sustainability and Sweden is the top state from both the environmental and energy generation assessments [

36], [

37].

4. About Organic Growth Theory

A sharp prospect and vision for

‘impact’ and a strategy that supports such a vision is the basic element of a forward-thinking way of advancing corporate growth. In such perspective, significance, quantifiability and scalability are the leading theories. Equally, impact-driven growth involves corporates to put in place effective clarity instruments to leverage the gains of this progressive approach [

38] [

12]. OGT has three main assumptions:

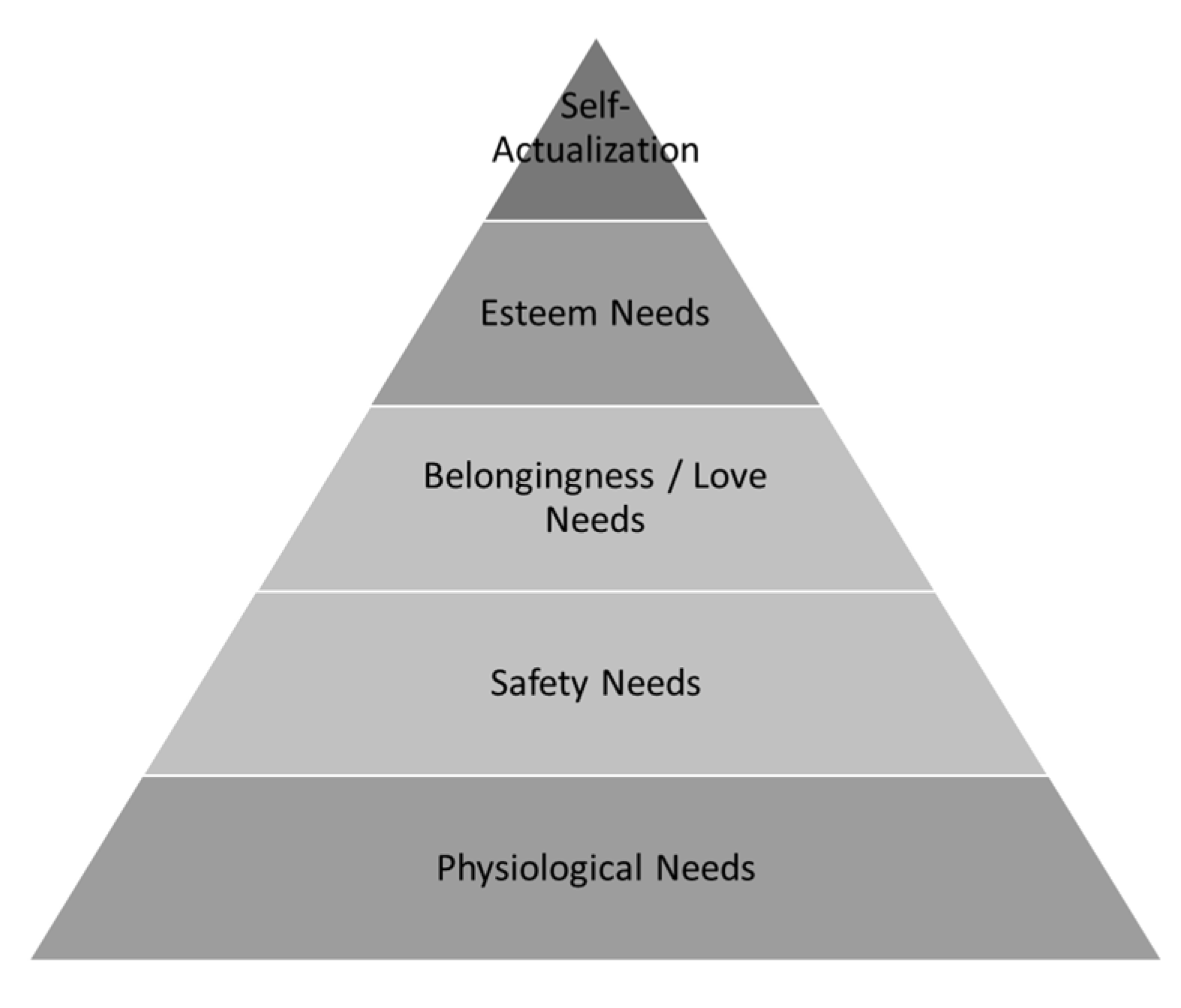

In the OGT structure, Foundation Corporates (Founcorps for shortness) is described as the next generation of corporates. Founcorps aim on getting profound motives and impactful visions to a corporate growth. As stated above, the proposed OGT structure is based on two known theories: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the concept of ecological thinking [

2] [

38]. The former is an interactive purpose theory in psychology comprising a five-tier model of human requirements, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid, as illustrated in

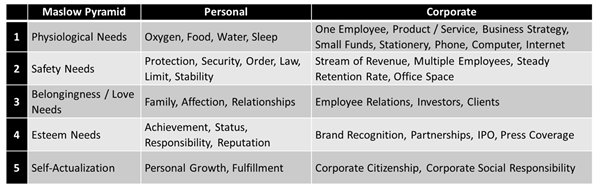

Figure 1.

Individuals cannot serve more advanced needs unless, the needs in the bottom of the hierarchy are fulfilled. From the bottom of the hierarchy upwards, the needs are physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. These stages have been transformed to the corporate, as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation of Maslow Pyramid for individual and corporate.

Table 1.

Correlation of Maslow Pyramid for individual and corporate.

For corporates, it starts from basic needs for strategy and funds before leading to sustainability, corporate citizenship and corporate social responsibility (CSR). An interesting example illustrating this point is the case of Aramco [

3], the largest oil company in the world, since their entire CSR focus is on corporate citizenship. While all the CSR activities are appreciated and invaluable, it is important to evolve corporate structures to grow in a responsible way. The growth path is described in OGT (Organic Growth Theory) and the goal is that the corporates should evolve to be responsible entities called Founcorps (Foundation Corporates).

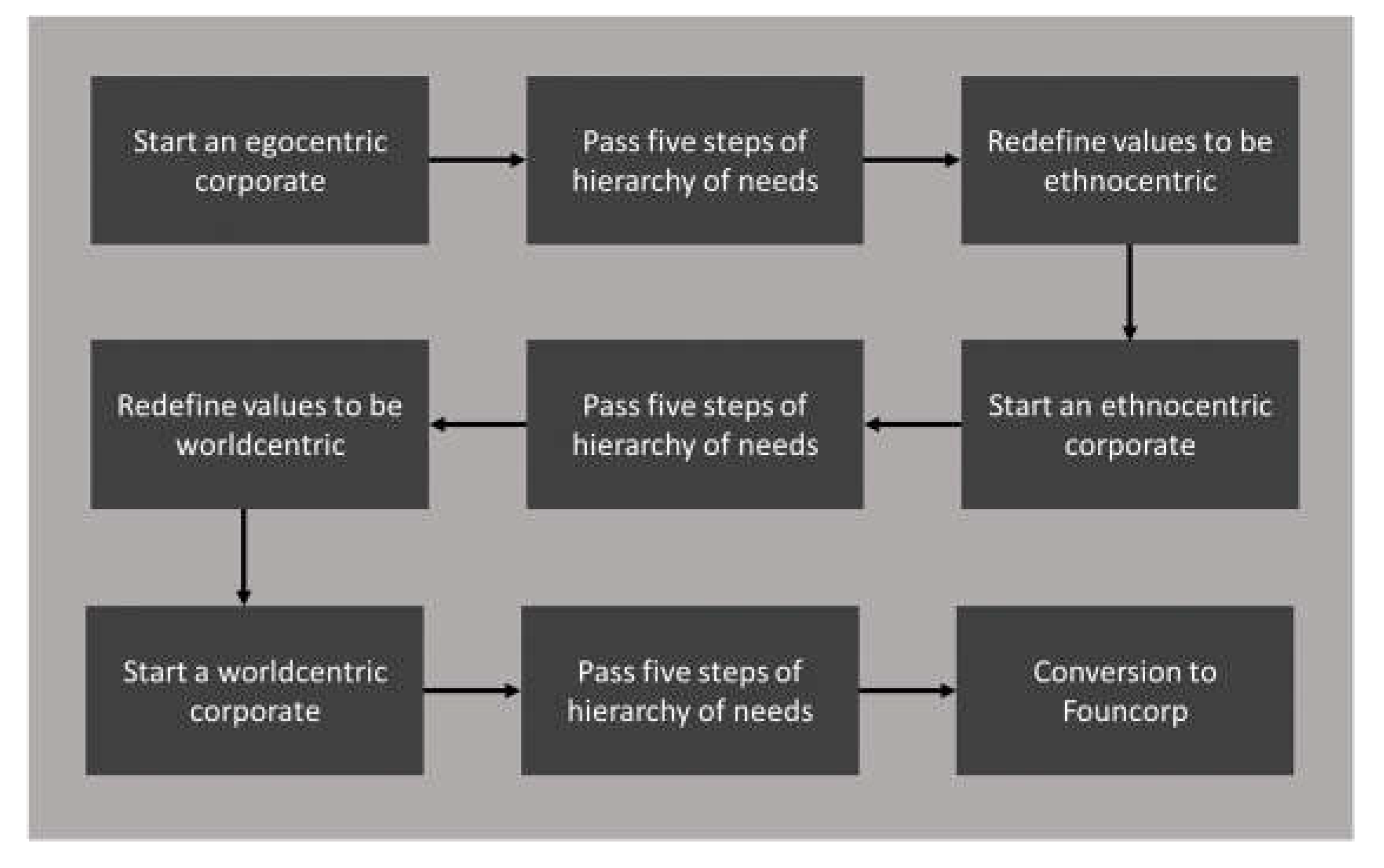

In the OGT framework, the five steps depicted in

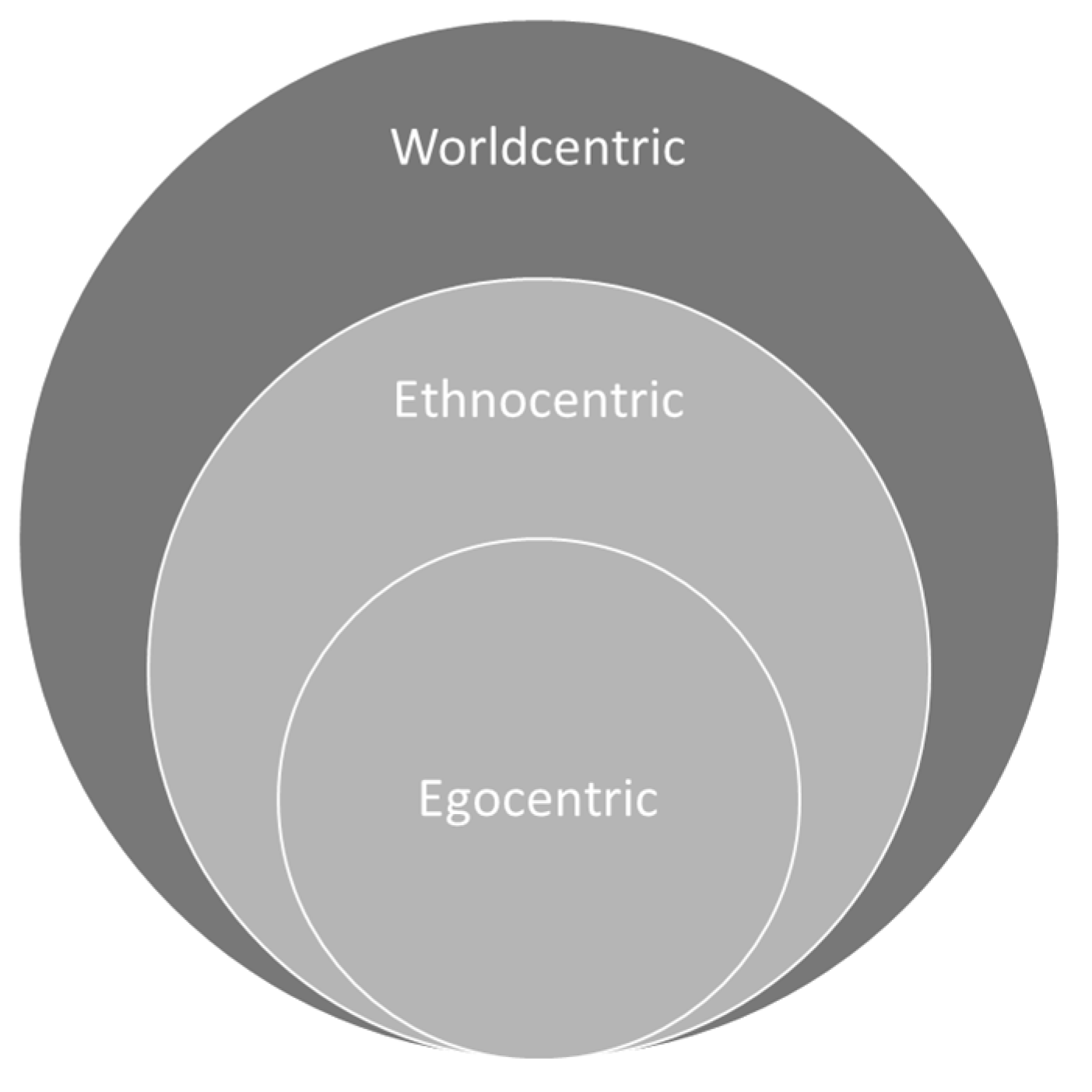

Table 1 need to be repeated in three different phases until a company can become a truly Founcorp. These three phases are based on the concept of ecological thinking [

2], and they are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Ecological thinking is a natural way for responsible corporates to work and grow. It allows the concerned corporates to be part of the natural rebalancing process in the lives of people and nature [

4]. It also enables corporate concerns to serve the entire interdependent web of nature and life. Furthermore, it makes the corporate concerns valuable to the people and nature. To summarize, the nine steps required to become a Founcorp are shown in

Figure 3.

As shown in

Figure 3, it is necessary to take the 5 steps of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to grow. However, this is not enough. Those 5 steps need to be taken in line with the 3 phases of ecological thinking [

2]. These steps and phases constitute what we define as a Founcorp, which is world centric with meaningful reasons and impactful visions for growth.

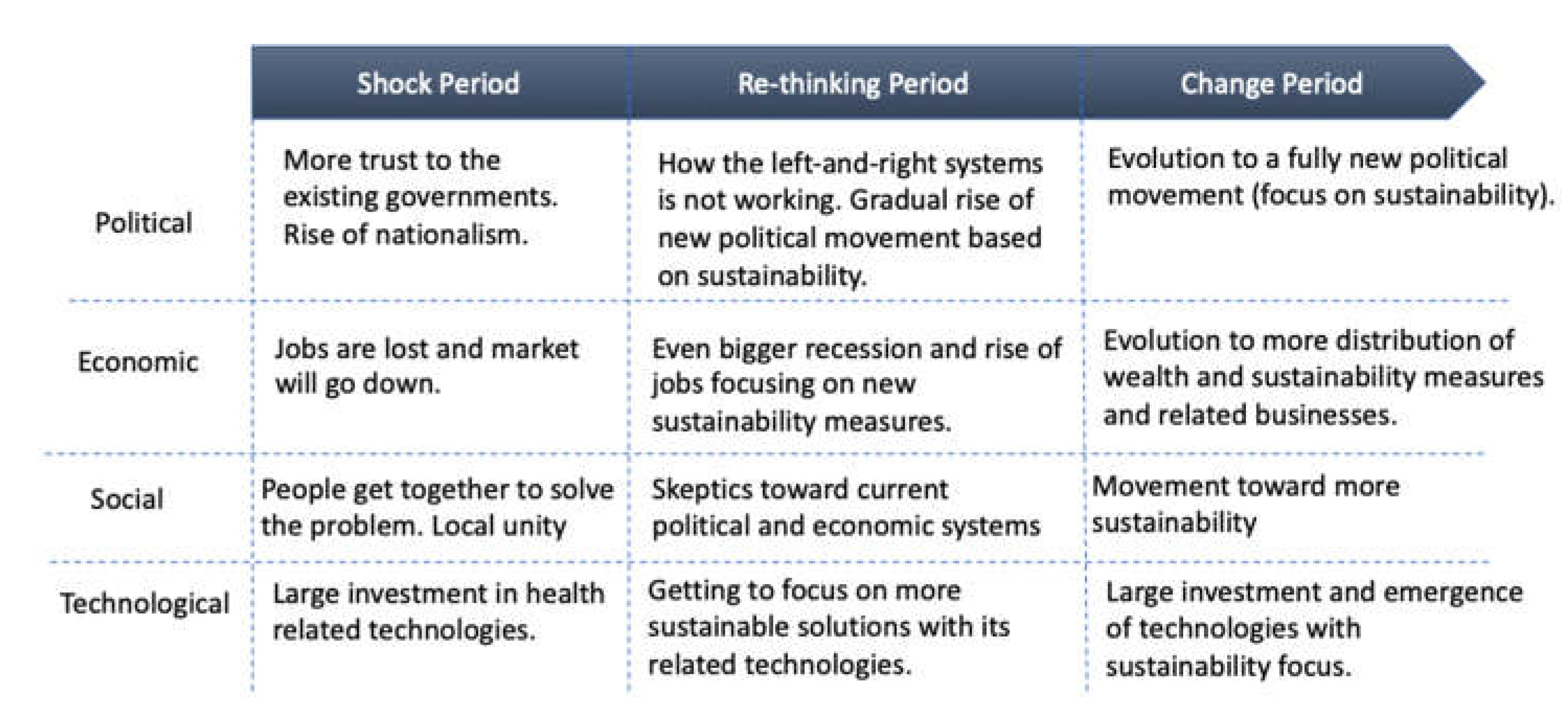

5. Organic Growth Theory for Global Sustainable Competitiveness

A PEST analysis (Political, Economic, Socio-cultural and Technological) of the COVID-19 effects on our societies was made. PEST describes a framework of macro-environmental factors used in the environmental inspecting part of strategic management. It provides an indication of the several macro-environmental factors to be taken into consideration to study the effect of an external factor (in this case corona visor pandemic). It is a strategic tool for understanding market growth or drop, overall status, potential and trend for operations. May of my predications have come true as described in the following figure:

Figure 4.

PEST analysis for COVID-19 effects on our societies.

Figure 4.

PEST analysis for COVID-19 effects on our societies.

We are now in re-thinking phase, and we can see that lots of movements are toward sustainability. The ppoliticians used to see sustainability additional overhead cost for risk mitigation and making ‘compensating’ positive impact. The world has reached a turning point of instability, mainly due to climate change but also by appearance of COVID-19, so that more investment on non-sustainable investment alternatives has created existential threat to all of us. On the other hand, a parity of the technology cost for sustainable investment has been reached in comparison with non-sustainable alternatives. Therefore, our proposed Organic Grow Theory [

1] introduces a step-by-step approach so that the world’s economy can grow and create more jobs deprived of compromising the capacity of future generations to meet their needs. Wortry (World Country as it will be described in the next section) is our proposed way of governing a country to address the above challenges and it would be needed to direct countries to evolve and being responsible for our planet.

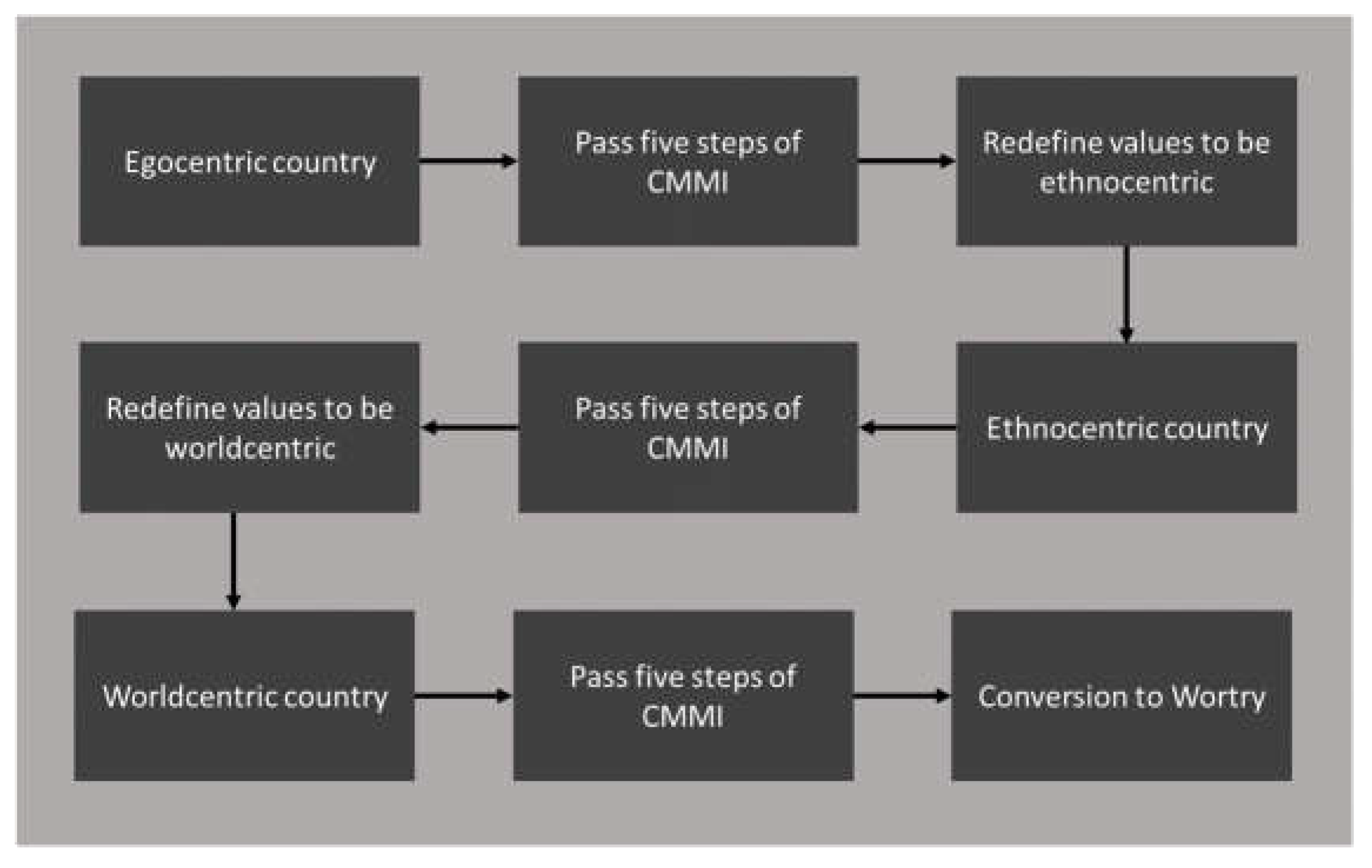

5.1. Organic Growth Theory for countries

Therefore, our proposed Organic Grow Theory [

1] introduces a step-by-step approach so that the world’s economy can grow and create more jobs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Wortry (World Country) is our proposed way of governing a country to address the above challenges and it would be needed to direct countries to evolve and being responsible for our planet. This is shown graphically in

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Organic Growth Theory for countries.

Figure 5.

Organic Growth Theory for countries.

There is a different between original OGT and the one used in this paper. The figure above introduces OGT 2.0 in which the hierarchy of needs is replaced by Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) [

39] [

28] as it will be described more in the next sections.

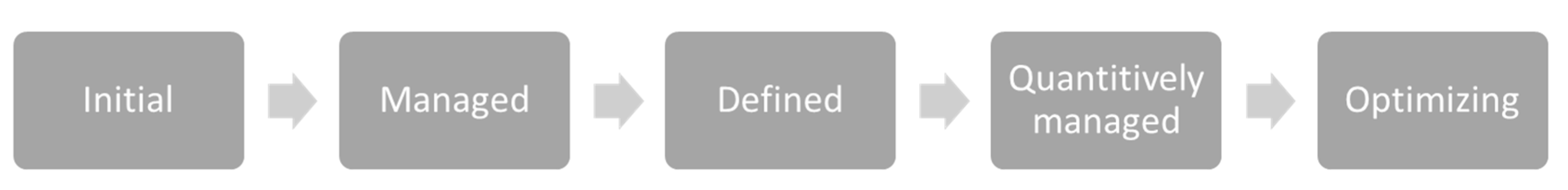

5.2. Capability Maturity Model Integration

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) is a process level improvement tool. In CMMI, a maturity level is a well-defined evolutionary plateau toward achieving a mature process. The five levels in CMMI are shown in the following figure:

Figure 6.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI).

Figure 6.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI).

Each country of block of power can be in any of those three levels (egocentric, ethnocentric or world centric) and each level the country can be ranked in any of the five steps in CMMI. Therefore, there will be in total 15 levels in which 1 indicates an egocentric country with initial maturity and 15 is a world centric country with optimizing maturity.

5.3. Sustainable Development Goals

In this paper, SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) are used as a tool to investigate how three major blocks of economy (USA, EU and China) have evolved to be a Wortry or devolved and how COVID-19 has influenced such change [

2]. The SDGs are grouped to Economy, Society and Environment [

3] [

40] in the following figure:

Figure 7.

Grouping of sustainable development goals.

Figure 7.

Grouping of sustainable development goals.

This grouping has been used in the modelling and the analysis made for the purpose of this research [

41].

6. Results and future research direction

Those three areas are modeled with Marco economic measures for three major blocks of power (US, China and EU). These three blocks account for more than 60% of world GDP and GDP PPP is more than 10 000 USD.

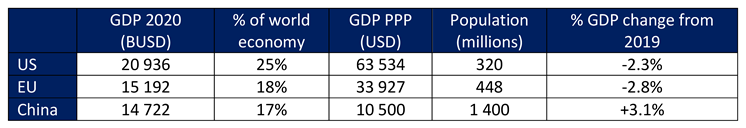

Table 2.

Three group of power for this study.

Table 2.

Three group of power for this study.

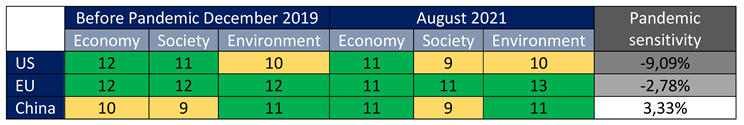

As it can be seen, China is the only economy that its GDP has increased during pandemic. The primary results from our model are shown in the following table. The red color indicates egocentric country (score 1-5), yellow indicates ethnocentric (score 6-10) and green is world centric (score 11-15).

6.1. COVID-19 Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis on the effects of COVID-19 based on the developed model has been performed. The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in the table below.

Table 3.

COVID-19 Sensitivity Analysis.

Table 3.

COVID-19 Sensitivity Analysis.

As it can be also seen, China is the only country which has increased its OGT scores to be a Wortry while the US and EU have seen a reduction in their scores. The average of all shows 3,03% reduction in the OGT scores.

To conclude, it is clear that the pandemic has paused the evolution of countries to be truly world centric countries. However, the recovery plans seem to be highly aligned with the OGT scores and it is expected that the scores by the end of 2022 to improve dramatically.

In the future, this research abd Organic Growth Theory will be exteded to the effects of other major events on global competiveness. These include war in the Ukraine or Irael-Palestine conflict.

References

- Karnama and R. Vinuesa, “Organic Growth Theory for Corporate Sustainability,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 20, p. 8523, 2020.

- Karnama and R. Vinuesa, “Organic growth theory for corporate sustainability,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Tracey, N. Phillips, and H. Haugh, “Beyond philanthropy: Community enterprise as a basis for corporate citizenship,” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 327–344, 2005.

- Davies, H. Haugh, and L. Chambers, “Barriers to social enterprise growth,” Journal of Small Business Management, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 1616–1636, 2019.

- T. Hák, S. Janoušková, and B. Moldan, “Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators,” Ecol Indic, vol. 60, pp. 565–573, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang, F. Kong, and Y. Choi, “Measuring sustainability performance for China: A sequential generalized directional distance function approach,” Econ Model, vol. 41, pp. 392–397, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Soppe, “Sustainable corporate finance,” Journal of business ethics, vol. 53, pp. 213–224, 2004.

- R. K. Singh, S. Luthra, S. K. Mangla, and S. Uniyal, “Applications of information and communication technology for sustainable growth of SMEs in India food industry,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 147, no. January, pp. 10–18, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Shrivastava and S. Hart, “Creating sustainable corporations,” Bus Strategy Environ, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 154–165, 1995.

- D. Antanasijević, V. Pocajt, M. Ristić, and A. Perić-Grujić, “A differential multi-criteria analysis for the assessment of sustainability performance of European countries: Beyond country ranking,” J Clean Prod, vol. 165, pp. 213–220, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tan, C. Shuai, L. Jiao, and L. Shen, “An adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) approach for measuring country sustainability performance,” Environ Impact Assess Rev, vol. 65, no. April, pp. 29–40, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Aras and D. Crowther, “Governance and sustainability: An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability,” Management Decision, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 433–448, 2008.

- Y.-K. Lee, “The relationship between green country image, green trust, and purchase intention of Korean products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z consumers,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 5098, 2020.

- Böhringer and P. E. P. Jochem, “Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability indices,” Ecological economics, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2007.

- W. Visser and N. Tolhurst, The world guide to CSR: A country-by-country analysis of corporate sustainability and responsibility. Routledge, 2017.

- F. Cucchiella, I. D’Adamo, M. Gastaldi, S. L. Koh, and P. Rosa, “A comparison of environmental and energetic performance of European countries: A sustainability index,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 78, no. April, pp. 401–413, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Bell and S. Morse, Sustainability indicators: measuring the immeasurable? Routledge, 2012.

- Moldan, S. Janoušková, and T. Hák, “How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and targets,” Ecol Indic, vol. 17, pp. 4–13, 2012.

- S. Corrente, S. Greco, F. Leonardi, and R. Słowiński, “The hierarchical SMAA-PROMETHEE method applied to assess the sustainability of European cities,” Applied Intelligence, vol. 51, no. 9, pp. 6430–6448, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Papathanasiou and N. Ploskas, “Multiple criteria decision aid,” Methods, examples and python implementations, vol. 136, p. 131, 2018.

- J.-J. Wang, Y.-Y. Jing, C.-F. Zhang, and J.-H. Zhao, “Review on multi-criteria decision analysis aid in sustainable energy decision-making,” Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 2263–2278, 2009.

- R. Arbolino, R. Boffardi, G. Ioppolo, T. L. Lantz, and P. Rosa, “Evaluating industrial sustainability in OECD countries: A cross-country comparison,” J Clean Prod, vol. 331, no. November 2021, p. 129773, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Diaz-Sarachaga, D. Jato-Espino, and D. Castro-Fresno, “Is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) index an adequate framework to measure the progress of the 2030 Agenda?,” Sustainable Development, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 663–671, 2018.

- J. Talberth, C. Cobb, and N. Slattery, “The genuine progress indicator 2006,” Oakland, CA: Redefining Progress, vol. 26, 2007.

- S. Dutta, B. Lanvin, and S. Wunsch-Vincent, “The global innovation index 2017,” Cornell University, INSEAD, & WIPO (Eds.), Global innovation index, pp. 1–39, 2019.

- Hsu and A. Zomer, “Environmental performance index,” Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, pp. 1–5, 2014.

- G. Van de Kerk and A. R. Manuel, “A comprehensive index for a sustainable society: The SSI—the Sustainable Society Index,” Ecological Economics, vol. 66, no. 2–3, pp. 228–242, 2008.

- L. P. Index, “Legatum Prosperity Index 2014.” 2015.

- G. Candan and M. Cengiz Toklu, “Sustainable industrialization performance evaluation of European Union countries: an integrated spherical fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and grey relational analysis approach,” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 387–400, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ligus and P. Peternek, “The Sustainable Energy Development Index—An Application for European Union Member States,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, p. 1117, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Karnama, J. A. P. Lopes, and M. A. Da Rosa, “Impacts of Low-Carbon Fuel Standards in transportation on the electricity market,” Energies (Basel), vol. 11, no. 8, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Karnama, E. B. Haghighi, and R. Vinuesa, “Organic data centers: A sustainable solution for computing facilities,” Results in Engineering, vol. 4, p. 100063, 2019.

- Karnama, “ENERGY X. 0: Future of energy systems,” Results in Engineering, vol. 3, p. 100029, 2019.

- Perujo and B. Ciuffo, “The introduction of electric vehicles in the private fleet: Potential impact on the electric supply system and on the environment. A case study for the Province of Milan, Italy,” Energy Policy, vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 4549–4561, 2010nt. [CrossRef]

- F. Cucchiella, I. D’Adamo, M. Gastaldi, S. C. L. Koh, and P. Rosa, “A comparison of environmental and energetic performance of European countries: A sustainability index,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 78, pp. 401–413, 2017.

- Mignon and L. Winberg, “The role of public energy advising in sustainability transitions–empirical evidence from Sweden,” Energy Policy, vol. 177, p. 113525, 2023.

- Mignon and L. Winberg, “The role of public energy advising in sustainability transitions–empirical evidence from Sweden,” Energy Policy, vol. 177, p. 113525, 2023.

- E. de Lange, T. Busch, and J. Delgado-Ceballos, “Sustaining sustainability in organizations,” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 110, no. 2, pp. 151–156, 2012.

- J. Torrecilla-Salinas, J. Sedeño, M. J. Escalona, and M. Mejías, “Agile, Web Engineering and Capability Maturity Model Integration: A systematic literature review.,” Inf Softw Technol, vol. 71, pp. 92–107, 2016.

- P. Hirst, “The global economy—myths and realities,” Int Aff, vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 409–425, 1997.

- R. Vinuesa et al., “The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).