Submitted:

02 December 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

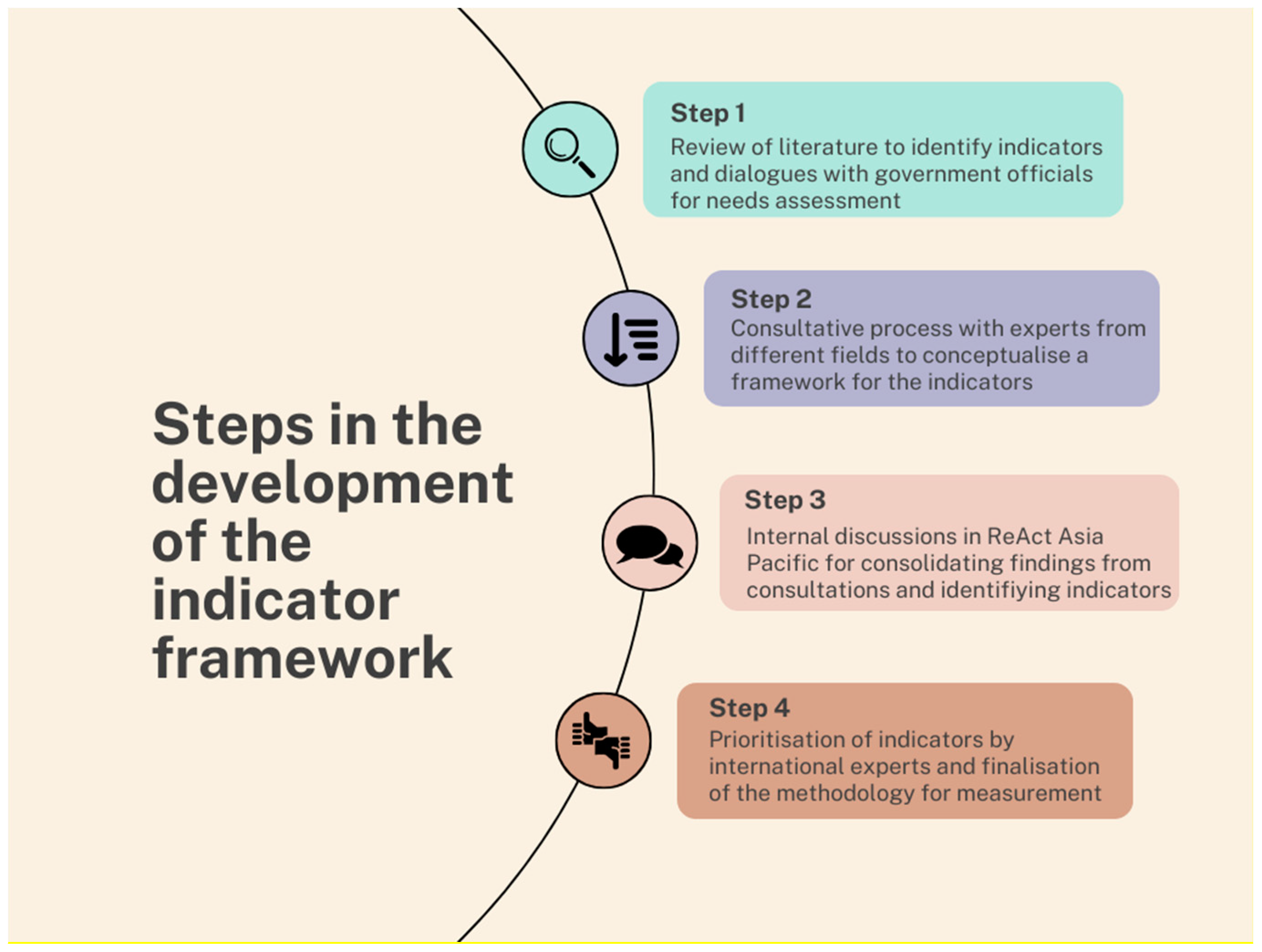

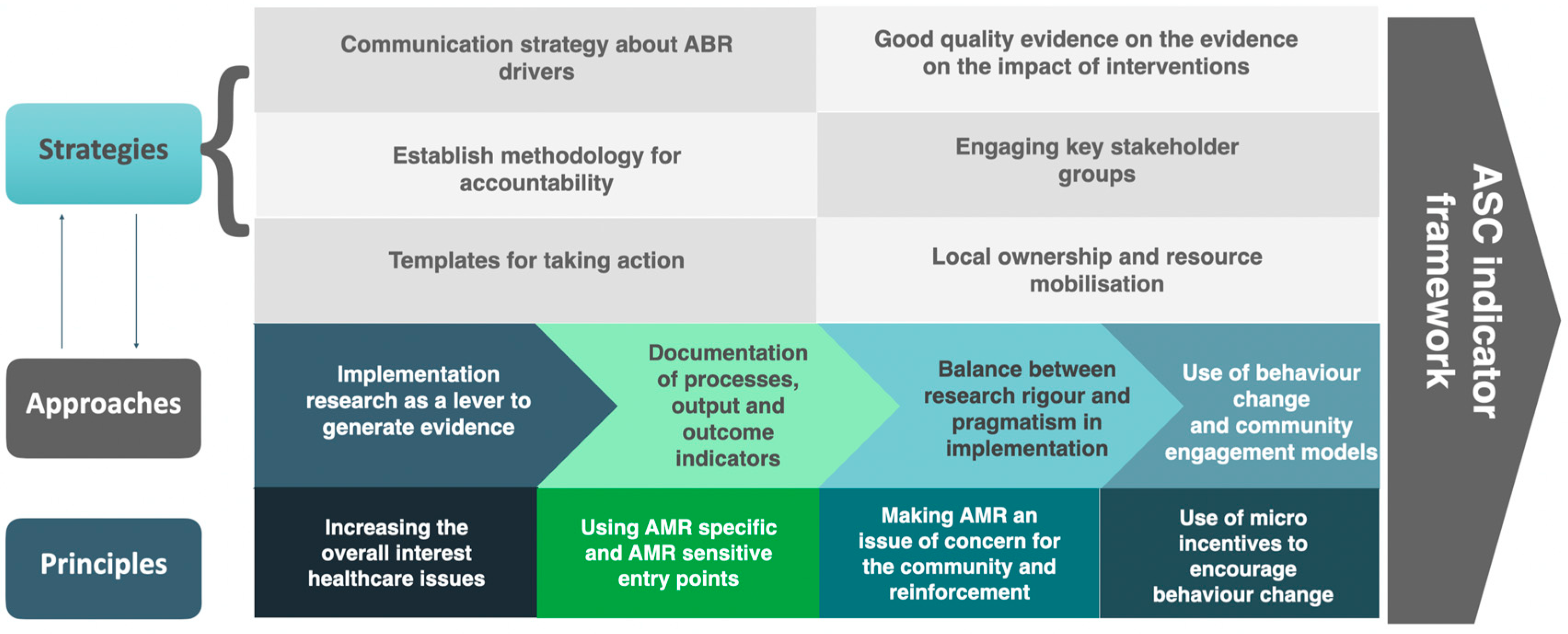

2. Methods:

- Appropriateness of the indicator in measuring ABR-specific/sensitive activities at the community level in local communities

- Feasibility of measurement in Low and Income Country (LMIC) countries contexts

- Validity of the indicator in detecting changes in response to intervention on the ground

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AMR Review Paper - Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations_1.pdf.

- V, J., Olga B. ,Irwin, Alec,Berthe,Franck Cesar Jean,Le Gall,Francois G. ,Marquez,Patricio Drug-resistant infections : a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2) : final report. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/323311493396993758/final-report (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Ayukekbong, J.A.; Ntemgwa, M.; Atabe, A.N. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000–2018: a spatial modelling study - The Lancet Planetary Healt. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00280-1/fulltext (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241509763 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Target Global Database for the Tripartite Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Country Self-assessment Survey (TrACSS). Available online: http://amrcountryprogress.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- No time to Wait: Securing the future from drug-resistant infections. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Mathew, P.; Sivaraman, S.; Chandy, S. Communication strategies for improving public awareness on appropriate antibiotic use: Bridging a vital gap for action on antibiotic resistance. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wind, L.L.; Briganti, J.S.; Brown, A.M.; Neher, T.P.; Davis, M.F.; Durso, L.M.; Spicer, T.; Lansing, S. Finding What Is Inaccessible: Antimicrobial Resistance Language Use among the One Health Domains. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiga, I.; Sidorchuk, A.; Pitchforth, E.; Stålsby Lundborg, C.; Machowska, A. ’If you want to go far, go together’-community-based behaviour change interventions to improve antibiotic use: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.; Cooke, P.; Ahorlu, C.; Arjyal, A.; Baral, S.; Carter, L.; Dasgupta, R.; Fieroze, F.; Fonseca-Braga, M.; Huque, R.; et al. Community engagement: The key to tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) across a One Health context? Glob. Public Health 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontiers | Challenges and Lessons Learned in the Development of a Participatory Learning and Action Intervention to Tackle Antibiotic Resistance: Experiences From Northern Vietnam. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.822873/full (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Shukla, S. Kerala: India’s Highest HDI, a Testament to Economic Advancement. Medium 2023.

- Individualism-collectivism and personality - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11767823/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Meyer, H.-D. Framing Disability: Comparing Individualist and Collectivist Societies. Comp. Sociol. 2010, 9, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu M.G., S.; Ghosh, D.; Gupte, J.; Raza, M.A.; Kasper, E.; Mehra, P. Kerala’s Grass-roots-led Pandemic Response: Deciphering the Strength of Decentralisation; Institute of Development Studies (IDS), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Azeez, E.P.A.; Anbuselvi, G. Is the Kerala Model of Community-Based Palliative Care Operations Sustainable? Evidence from the Field. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2021, 27, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benny, G.; D., H.S.; Joseph, J.; Surendran, S.; Nambiar, D. On the forms, contributions and impacts of community mobilisation involved with Kerala’s COVID-19 response: Perspectives of health staff, Local Self Government institution and community leaders. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0285999. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, V. Kerala’s resilience comes from community participation in policies … besides high investments in health and education. Times India.

- Noorihekmat, S.; Rahimi, H.; Mehrolhassani, M.H.; Chashmyazdan, M.; Haghdoost, A.A.; Ahmadi Tabatabaei, S.V.; Dehnavieh, R. Frameworks of Performance Measurement in Public Health and Primary Care System: A Scoping Review and Meta-Synthesis. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegegne, S.G.; MKanda, P.; Yehualashet, Y.G.; Erbeto, T.B.; Touray, K.; Nsubuga, P.; Banda, R.; Vaz, R.G. Implementation of a Systematic Accountability Framework in 2014 to Improve the Performance of the Nigerian Polio Program. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213 Suppl 3, S96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karris, M.Y.; Dubé, K.; Moore, A.A. What lessons it might teach us? Community engagement in HIV research. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2020, 15, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cars, O.; Chandy, S.J.; Mpundu, M.; Peralta, A.Q.; Zorzet, A.; So, A.D. Resetting the agenda for antibiotic resistance through a health systems perspective. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1022–e1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldane, V.; Chuah, F.L.H.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, S.R.; Koh, G.C.H.; Seng, C.K.; Legido-Quigley, H. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PloS One 2019, 14, e0216112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaz, A.; Hanney, S.; Borst, R.; O’Shea, A.; Kok, M. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Family Health Survey. Available online: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/kerala.shtml (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/site/progresskorea/43586563.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Mapping and assessing indicator-based frameworks for monitoring circular economy development at the city-level - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221067072100651X (accessed on 28 November 2023).

| Indicator |

Total score Appropriateness (Out of 100) |

Total score Feasibility (Out of 100) |

Total score Validity (Out of 100) |

Mean total score (Out of 100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Awareness about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance among general public | 77 | 75 | 70 | 74.0 |

| 2. Over-the-counter availability of antibiotics in retail pharmacies in the area | 85 | 85 | 73 | 81.0# |

| 3. Proportion of Healthcare facilities that have implemented a written Infection Prevention & Control (IPC) plan | 65 | 80 | 60 | 68.3 |

| 4. Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services | 85 | 80 | 82 | 82.3# |

| 5. Proportion of healthcare facilities with a written antibiotic protocol for at least three disease/syndrome conditions caused by bacteria | 78 | 80 | 80 | 79.3# |

| 6. Percentage of Access antibiotics (as per Aware classification of WHO) in total antibiotics dispensed in out-patient settings at healthcare facilities | 92 | 83 | 83 | 86.0# |

| 7. Proportion of Healthcare facilities which are accredited by any standard agency (government/private) for quality assurance in delivery of services | 77 | 75 | 70 | 74.0 |

| 8. Percentage of suspected Urinary Tract Infections (community or healthcare associated) being subjected to culture and sensitivity testing | 77 | 67 | 73 | 72.3 |

| 9. Prevalence of stunting (height for age <-2 standard deviation from the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards) | 48 | 67 | 48 | 54.3 |

| 10. Average under-5 mortality rate (number of deaths among children under 5 years of age compared to number of live births) in the area for the last 3 years | 72 | 83 | 63 | 72.6 |

| 11. Average Out-Of-Pocket expenditure on healthcare by households in the area | 62 | 68 | 60 | 63.3 |

| 12. Access to Health | 70 | 68 | 65 | 67.6 |

| 13. Coverage for pediatric vaccines listed in the immunization schedule published by the competent national authority | 90 | 87 | 88 | 88.3# |

| 14. Availability of laboratory services in Healthcare Facilities within the community | 75 | 78 | 75 | 76.0 |

| 15. Hygiene facilities in primary and secondary schools in the community | 90 | 87 | 92 | 89.6# |

| 16. Educational initiatives in the last one year to increase awareness about antibiotic or biocide use among farmers | 80 | 80 | 70 | 76.6# |

| 17. Use of Highest Priority Critically Important Antibiotics in agriculture | 88 | 80 | 85 | 84.3# |

| 18. Regulatory oversight regarding best farm management practices and biosecurity measures | 78 | 78 | 70 | 75.3 |

| 19. Presence of veterinary health facilities in the community | 78 | 80 | 75 | 77.6# |

| 20. Vaccination coverage for farm animals in the community | 82 | 75 | 72 | 76.3 |

| 21. Government Subsidies or Incentives for infrastructural improvement in farms for better infection control practices | 70 | 78 | 65 | 71.0 |

| 22. Availability of veterinary laboratory services for disease diagnostics | 85 | 83 | 82 | 83.3# |

| 23. Incentive system for farmers who make products without routine use of antibiotics | 80 | 70 | 73 | 74.3 |

| 24. Presence of schemes to promote local or household-based production of food | 63 | 73 | 63 | 66.3 |

| 25. Proportion of wastewater treated using any established wastewater treatment technologies, as per WHO's guidelines on Sanitation & Health (2019) | 80 | 77 | 80 | 79.0# |

| 26. Biomedical waste management system in healthcare facilities | 92 | 83 | 82 | 85.6# |

| 27. System for disposal of antibiotics and other medicinal waste generated from households | 85 | 65 | 75 | 75.0 |

| 28. Use of chemical/synthetic pesticides, herbicides and other biocides in farms | 83 | 72 | 82 | 79.0# |

| 29. Farm waste contaminating water resources in the community | 87 | 70 | 80 | 79.0# |

| 30. Proportion of households having access to Individual Household Latrine (IHHL) with water supply, within the premises of their house | 88 | 87 | 55 | 76.6# |

| 31. Proportion of population covered by at least one social insurance or assurance schemes for health protection | 62 | 70 | 58 | 63.3 |

| 32. Proportion of population below the nationally accepted poverty line | 68 | 78 | 65 | 70.3 |

| 33. Proportion of children between ages 5 and 14 receiving nutritional support from government | 68 | 78 | 68 | 71.3 |

| 34. Female Literacy Rate | 72 | 77 | 80 | 76.3 |

| 1 | Hygiene facilities in primary and secondary schools in the community |

| 2 | Access to Individual Household Latrine (IHHL) with water supply, in households |

| 3 | Coverage for pediatric vaccines as per the national immunization schedule |

| 4 | Percentage of Access antibiotics (as per AWaRe classification of WHO) in total antibiotics dispensed in outpatient settings at healthcare facilities |

| 5 | Antibiotic protocols in healthcare facilities |

| 6 | Over-the-counter (OTC) availability of antibiotics in retail pharmacies in the area |

| 7 | Access to safely managed drinking water services |

| 8 | Use of Highest Priority Critically Important Antibiotics in Agriculture |

| 9 | Presence of functional veterinary health facilities and services in the community |

| 10 | Veterinary laboratory services for disease diagnostics |

| 11 | Educational initiatives on antibiotic use among farmers |

| 12 | Biomedical waste management system in healthcare facilities |

| 13 | Treatment of wastewater generated in households |

| 14 | Use of chemical/synthetic pesticides, herbicides and other biocides in farms |

| 15 | Farm waste contaminating water resources in the community |

| Indicator | Performance of the community | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hygiene facilities in primary and secondary schools in the community | Good | Reasonable | Inadequate | 3 |

| Access to Individual Household Latrine (IHHL) with water supply, in households | All | Most | Some | 3 |

| Coverage for pediatric vaccines as per the national immunization schedule | High | Reasonable | Low | 3 |

| Percentage of Access antibiotics (as per AWaRe classification of WHO) in total antibiotics dispensed in outpatient settings at healthcare facilities | High | Reasonable | Low | 2 |

| Antibiotic protocols in healthcare facilities | All | Some | None | 2 |

| Over-the-counter (OTC) availability of antibiotics in retail pharmacies in the area | Poor OTC availability | Partial OTC availability | Free OTC availability | 1 |

| Access to safely managed drinking water services | All | Most | Some | 3 |

| Use of Highest Priority Critically Important Antibiotics in Agriculture | None | Some | High | 2 |

| Presence of functional veterinary health facilities and services in the community | Fully Functional | Semi-functional | Not functional | 3 |

| Veterinary laboratory services for disease diagnostics | Fully Functional | Semi-functional | Not functional | 2 |

| Educational initiatives on antibiotic use among farmers | Fully Functional | Semi-functional | Not functional | 1 |

| Biomedical waste management system in healthcare facilities | All | Some | None | 2 |

| Treatment of wastewater generated in households | All | Most | Some | 2 |

| Use of chemical/synthetic pesticides, herbicides and other biocides in farms | Low | Significant | High | 2 |

| Farm waste contaminating water resources in the community | High | Some | None | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).