1. Introduction

Emily Howard Jennings Stowe (see

Figure 1) is acclaimed as the first female school principal (Feldberg 1994), and the first white (Backhouse 1991, 159) openly female (Raymond 2008a) physician to practice medicine in Canada (Backhouse 1991, 159). As well, she is a renowned founding champion of women's rights (Backhouse 1991, 168) representing Canada’s foremost suffragette during her day (Feldberg 1994). More than anyone else, she is recognized as starting the women’s movement in Canada (Hacker 1974, 18).Yet, relatively little has been written on the life-changing events that permitted her to pioneer in these fields, apart from general non-academic books intended for children (Laflamme and Lamarre 2021), (McCallum 1989), (Stanbridge 2005), (Waxman 2015). Why understanding her life-changing events is important is that it is these events that determined her ability to be recognized as a trailblazer in each of these areas, while also fulfilling the expected late 19

th century role as an Establishment (Feldberg 1994) daughter, wife, and mother (Bacchi 1978, 471).

According to a relatively recent article on Emily Stowe, “there are huge gaps in our modern knowledge of Emily Stowe. Before her death in 1903, she destroyed most of her records — everything from her medical practice – and many personal papers as well” (Spears 2017). For this reason, interpreting Stowe’s life-changing events now requires a new method. To reveal the relationships among the life-changing events in Emily Stowe’s life, the method used will be a unique narrative research process developed by the author—one that corresponds with current directions in narrative research (De Fina 2021)(Silva and Cain 2019). Here, narrative research represents a form of qualitative research that examines varying perspectives of a constructed story in making experience comprehensible (Ntinda 2018) where data are treated as stories resulting from interpreting how human actions are related to the social context in which they occur (Renjith et al. 2021). This process, reported on in a number of previous publications by the author (Nash 2020), (Nash 2021), (Nash 2022), will take Emily Stowe’s story and develop it into a narrative with a particular point of view in response to questions posed regarding her life, ranging from the most objective and specific to those that are subjective and more general. This will be accomplished by following a prescribed order of question-asking—when, where, who, what, how, and why—in relation to twenty-two identified life changing events where “life-changing” means that her life took a different course as a result of the event (Bhatti, Salek, and Finlay 20, 13). As such, this investigation is not intended as a full account of all activities in Stowe’s life. Some things, among others, that are not included are Stowe’ vacations (Stowe 1901)(Fryer 1991, 117), friendship with Susan B. Anthony (Ray 1978, 37), the additional year she studied medicine at the University of Toronto (Hamilton 2017, 1023)), and the influence she had on her daughter’s career in becoming “the first woman doctor fully trained in Canada” (Baros-Johnson 2004). Only those events resulting in a change in her own life-direction will be considered. In this way, although, for example, it was significant in the history of medicine that Stowe was instrumental in creating a free dispensary for women in 1898 (Davidson 2014), as it did not change her life trajectory, here, it is not discussed.

This technique to be used in assessing these life-changing events is valuable because the point of view developed then represents the beliefs (Alvesson and Einola 2019) Emily Stowe held in the choices she valued during her life. In this regard, it is these choices that are the focus of this investigation into her life-changing events. Among the various narrative research methodologies (Rodríguez-Dorans and Jacobs 2020), this type of process depends on no presuppositions nor initial hypotheses to direct the investigation. Using this narrative research technique, what it was that guided the life choices of Emily Stowe is revealed from relationships among the facts collected. The conclusions drawn are those that arise from qualitatively interpreting the results (Willig 2017) in answer to the questions asked.

The purpose of using this process is to reveal relationships among the life-changing events in Emily Stowe’s life in a manner that makes these relationships easier to identify, compare, and develop. In this regard, the twenty-two life changing events are specified through chronological ordering divided into four different aspects of her life: personal, teacher, physician, and suffragette. The order of questions posed—when, where, who, what, how, and why—will be characterized related to each of these four aspects of Stowe’s twenty-two life changing events.

Distinctive in this method of gathering materials is that the story developed regarding Emily Stowe’s life examines more than what happened to her throughout her life in relation to particular the demographic characteristics (Kaufman 2014) that would be represented by age, gender, race, education, and income level. Instead of considering each of these characteristics as separate variables, the concentration is on the important events in Stowe’s life and the associations among the full range of questions that can be asked regarding each of these important events. Although demographic research investigates populations as inclusively as possible in gaining a clear, broad and deep perception of all relevant conditions (Burton 2019) in identifying the casual mechanisms that direct them over time (Huinink and Brüderl 2021), this is accomplished concerning a particular research question starting from a hypothesis (J. C. Caldwell and Hill 2023). In contrast, the form of narrative research undertaken here lets the events of Stowe’s life determine the important demographic variables at each point in her life. These variables and their relationship to how they affected Stowe’s life are therefore influenced by the type of importance that the events had on her life at a particular time.

Also specific to this form of narrative research is that the aspects of Emily Stowe’s life will be examined in considering her perspective alone. As an example, the date of Stowe’s husband being diagnosed with tuberculosis is not recorded in this account, as this is not an event in Stowe’s life per se. However, in contrast, dates and actions she took in response to his illness are a focus of this account. This method is differentiated from other forms of narrative research that place the life of a subject within a particular strategy (Argyres et al. 2020), mindset (Dweck and Yeager 2019), epoch (Mignolo 2020), or in relation to other history-makers (Berger 2023). In contrast, the aim is to interpret Stowe’s story from her own beliefs and choices, rather than those made by others who were influential to her life at the time. Similarly, this work will not interpret Stowe’s life from concerns that are relevant to the current period in history (J. Hall, Gaved, and Sargent 2021). Although making history currently relevant can be a reason for taking the initiative to reconstruct a history (Nurminen 2019), it is not the concern of this narrative research to be conducted on Emily Stowe’s twenty-two life-changing events.

What is concluded from this endeavor is that although the often-repeated story of Emily Stowe portrays her as a fighter and champion (Emily Howard Jennings Stowe, M.D. 1867 (1831-1903) 2022), the narrative that is developed through this process shows that she achieved these results to the extent considered appropriate by her family and social class, but only when she was encouraged by important people in her life to take on these roles by their convictions and circumstances. As an individual, she was cautious, extremely bright, dedicated to learning, and intellectually competitive. As such, without the beliefs and needs of her family and social class to encourage her to act, she herself valued a calm academic approach to life focused on intelligently-focused homemaking that she purported as the woman’s most important contribution (Bacchi 1978, 460), rather than the public role she felt she needed to assume as a pioneer teacher, physician, and suffragette.

Figure 1.

Portrait of Emily Stowe (Simpson c.1895).

Figure 1.

Portrait of Emily Stowe (Simpson c.1895).

2. Materials and Methods

The materials and methods to be used are those that arise through engaging in the narrative process created by the author by the particular questions asked in relation to Stowe’s life.

For the “when” questions, the materials gathered are the dates that are recorded in the dictionary and encyclopedia entries concerning Emily Stowe, in blog posts and in academic books written about Emily Stowe, as well as newspaper articles and documents of the time. The method has additionally been used by the author to create four timelines of Stowe’s activities divided into personal events; years as a teacher; career as a physician; and work as a suffragette.

Answers to the ”where” questions come from identifying place names where events occurred on maps and in relation to notable features and locations of the jurisdictions in which she resided, learned, and worked. These include referencing various encyclopedias as well as a book, a video, blog post, and a journal article on Emily Stowe. Additionally, dates from newspaper articles and documents of the time are sourced. The method will involve highlighting the places Emily Stowe lived and visited in her life that had a life-changing effect on her life. The results are recorded in relation first to a historical map and then a generic map including what is now southern Ontario and the mid northern to the northeastern United States. The historical map records the boundary of the jurisdiction owned by Emily Stowe’s family into which she was born. The present-day map color-codes the locations where events occurred in relation to which of the four aspects of her life are represented by a particular point on the map.

“Who” questions have answers concerning people to have had a life-changing effect on her life. These are reported in dictionary and encyclopedia entries on Emily Stowe, various peer reviewed publications, an academic book, and a video, as well as in newspaper articles, and a document written regarding Emily Stowe during the time. The method produces a listing of important contacts for each of the four aspects of her life.

Regarding “what” questions: answers to these provide the details on the actual occurrence related to a particular event in Emily Stowe’s life. The information to answer “what” questions comes from dictionaries, journal articles, books, a video, as well as newspaper articles, and documents of the time. These answers provide what is recognized as the story of the narrative in the use of prior world knowledge constructed as an organized global representation of the information (Silva and Cain 2019).

“How” questions answered concerning the way in which Stowe (1) conducted her personal life; (2) became a teacher and then principal; (3) trained to be, and practiced as, a physician; and (4) pursued her role as a suffragette, are informed by a dictionary entry, peer reviewed publications and academic books written about Emily Stowe and with respect to newspaper articles of the time. Answers to these questions list the details of her methods regarding her personal life, being a teacher, practicing as a physician, and working as a suffragette.

The actual answers to “why” questions could only come from confessional pieces written by Emily Stowe herself or recorded in interviews of her during her lifetime. Newspaper articles written at the time that may have included interviewing Emily Stowe are the approximations used here to assess why certain events transpired in her life. However, the peer reviewed publications and books written about Emily Stowe have produced theories and speculations concerning why she undertook things as she did in each of the four aspects of her life, and these will be referenced. What is unique about the process undertaken here is that, in asking these ordered questions, why she undertook to make the decisions she did also will be gathered by interpreting the connections among all six of the type of questions asked for the four aspects of Emily Stowe’s life.

An important aspect of this method is that answers to each of the questions (providing the materials for this study) are in regards to only those pertaining to the particular question asked at a any one time. For example, although answering a “when” question could involve including information on where a certain event took place, who was there, what actually happened, how the event came about., and why it occurred, each of these additional points will be addressed only under the relevant section heading. As such, answers to “when” questions are found under “when” only, those of “where” questions solely under “where”, etc. The purpose in doing this is to clearly classify the information pertaining to Emily Stowe to make it easier to identify and permitting relevant comparisons to be developed.

3. Results

The results to be presented are divided into six sections, representing each of the six types of questions in relation to Emily Stowe’s life (when, where, who, what, how, why). Furthermore, these sections are then divided into subsections coinciding with the four different aspects of her life (personal, teacher, physician, suffragette).

3.1. When Were Stowe’s Life-Changing Events

When Stowe’s life-changing events occurred is summarized in

Table 1.

3.1.1. When—Personal

Emily Howard Jennings was born May 1, 1031. She married in November 1856 at the age of twenty-five and proceeded to have three children in 1857, 1861, and 1863 (Raymond 2008a) when she was twenty-six, thirty, and thirty-two. Her husband died in 1891 (Ray 1978, 40) when she was sixty. Thus, she was married for thirty-five years. Two years after the death of her husband, she broke her hip in 1863 when she was sixty-two. She recovered and lived until April 30, 1903, the day before her seventy-second birthday (Baros-Johnson 2004) (Raymond 2008a)(Fryer 1991, 120)—although one author claims she died on April 29, 1903 (Emily Howard Jennings Stowe, M.D. 1867 (1831-1903) 2022).

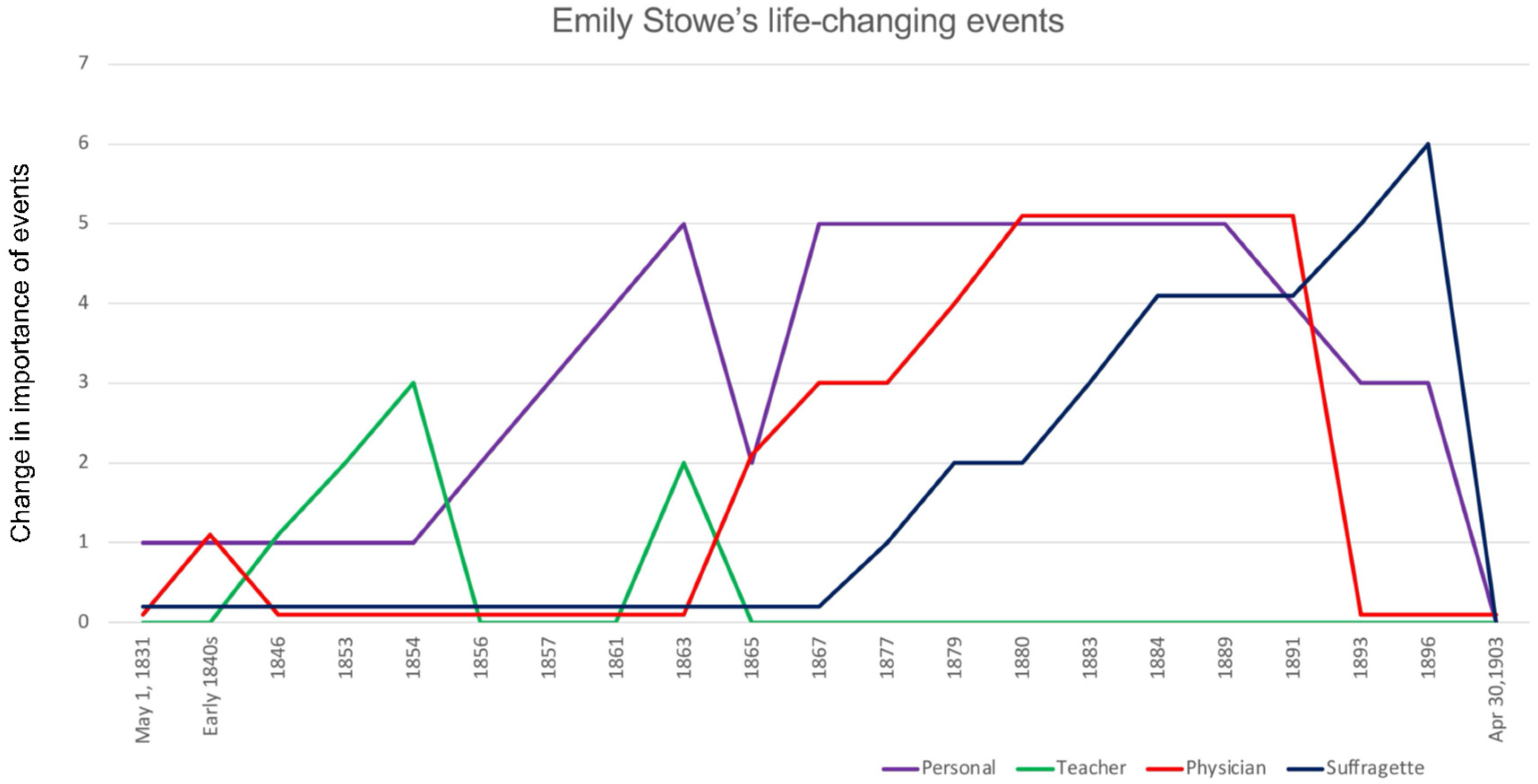

The timeline of Emily Stowe’s personal life is represented by the purple line of

Figure 2. As a woman from an Establishment Quaker family (Raymond 2008a), Stowe believed both in the importance of enriching her family and of having high aspirations for herself (Forster 2004, 245). As such, the purple line slopes upward upon her marriage and becomes increasing higher with the birth of each child. It dips downwards when her husband contracted tuberculous (Raymond 2008a) and she was separated from her husband and children during the time she was in medical school(Raymond 2008a). After returning to her family upon her graduation (Feldberg 1994), Stowe was able to maintain a high level of personal satisfaction based on the achievements of herself and her family life until, during her presidency of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association (Baros-Johnson 2004), her busy schedule meant she had less contact with her family because of travelling as a lecturer (Backhouse 1991, 168). This decrease in her personal life timeline deepened with the death of her husband, and worsened again with the breaking of her hip. From that point, her personal life remained at a low, relatively stable, level until her death.

3.1.2. When—Teacher

Although Emily Jennings was homeschooled herself (Raymond 2008a), she became a teacher at fifteen (Fryer 1991, 31) in 1846 and remained a teacher until she was twenty-two (Fryer 1991, 32), in 1853. Proceeding to teachers college between 1853-1854 (Ryerson 1854), she completed the requirements in six months (Fryer 1991, 33) between her twenty-second and twenty-third year. Upon graduation (Ray 1978, 10), she became a school principal between 1854-1856 (Raymond 2008a) between her twenty-third and twenty-fifth year. She took up teaching again in 1863-1865 when she was thirty-four, continuing with teaching until she was thirty six (Feldberg 1994).

The timeline with respect to Stowe’s role as a teacher is represented by the green line of

Figure 1. As can be seen in

Figure 1, in comparison with the other aspects of Stowe’s life, being a teacher was less important to Stowe regarding her choices. This is because being a teacher neither corresponded with her goal of excelling as a homemaker nor did it represent the intellectual stimulation she desired. The highest point on this line was when she became the first female principal in Canada (Raymond 2008a). Another, lesser, high point was when she was a teacher later in her life. Why it was not as important to her life choices was that she had to return to teaching reluctantly once her husband contracted tuberculosis.

3.1.3. When—Physician

Emily Jennings first became a practitioner of homeopathic medicine as an apprentice in the early 1840s, when she was a pre-teen (Cazalet 2001). She entered the medical school founded in 1864 (Davidson 2014, 10) in 1865, graduating in 1867 (Emily Howard Jennings Stowe, M.D. 1867 (1831-1903) 2022) between her thirty-fourth and thirty-sixth year. Once graduated, she began an unlicensed practice in 1867 and continued in this capacity until 1880 (Raymond 2008b)—from her thirty-sixth to her forty-ninth year. During this period, in her forty-eight year, August 1879, she was the defendant in a coroner’s inquest, and then a criminal case defendant in September 1879, concerning the death of one of her patients. Soon after being found not guilty in that case (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879), in 1880, at forty-nine, she became a licensed practicing physician (Forster 2004, 246)—remaining so until breaking her hip in 1893, when she was sixty two.

Stowe’s career as a physician is represented by the red line on

Figure 1. Although this career began before that of being a teacher, in that she apprenticed as a homeopath when she was a pre-teen, this apprenticeship was not of much life-changing importance in her life until she desired to go to medical school once she recognized she did not want to remain a teacher while her husband was apart from the family with tuberculosis. It was from this point onwards that her career as a physician progressed. She reached her first plateau as a physician in becoming an unlicensed practitioner. The final plateau was attained as she became a licensed practitioner. What is interesting to note is that the coroner’s inquest and the subsequent trial did not affect the trajectory of her career. Instead, it was her acquittal in the case that prompted her being able to achieve the goal of being licensed. The line regarding her life as a physician has a sudden descent with the breaking of her hip, causing her to discontinue her practice (Feldberg 1994); however, one source contends that she continued to practice medicine until her death (Kawartha Ancestral Research Association Inc. 2023).

3.1.4. When—Suffragette

At forty-five, in 1876, it is officially stated that Emily Stowe became a founder of the Toronto Women’s Literary Club (H. M. Ridley 1965, 5) (Toronto Women’s Literary Club, n.d.)—Canada’s first suffrage group (Forster 2004, 246)—although there is contradictory information placing the founding in 1877 (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903) (Emily Howard Jennings Stowe, M.D. 1867 (1831-1903) 2022). She remained as a continuing participant and travelling lecturer (Backhouse 1991, 168) with the Club until she was fifty-two, in 1883 (H. M. Ridley 1965, 5). Beginning two years after she founded the Club, in 1879, at age forty-eight, she began her campaign to have women admitted to medical schools in Canada. She achieved success in 1883 in this regard (Forster 2004, 247), when she was fifty-two. That same year she became vice president of the new Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association (Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association 1883), a position she held until 1889, when she was fifty-eight. During the period of her vice presidency, she addressed the provincial legislature (Baros-Johnson 2004) regarding passage of the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021) in 1884, at fifty-three. Following her vice presidency, in 1889, at fifty-eight, she became president of the renamed Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association (H. M. Ridley 1965, 7)—a position she held until her death in 1903 (Forster 2004, 247). Also, until then, beginning in 1893, she became a member of the National Council of Women of Canada, from age sixty-two to seventy-one. While a member of the Council, and president of the Association, she played the role of the Attorney General in a mock parliament regarding the inequalities of Canadian women (Forster 2004, 247). This occurred in 1896, when she was sixty-four.

Stowe’s work as a suffragette is pictured by the black line of

Figure 1. It is evident from that line that being a suffragette came late to her life, but, ultimately, provided the greatest satisfaction. Slowly, her abilities and inclination ascended to the point of her founding the Toronto Women’s Literary Club. Her court case plateaued her work as a suffragette, but it soon resumed and took an upward course regarding achieving admission of women to Canadian medical schools, and then addressing the provincial legislature regarding the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021). The highest point occurred when she, playing the part of the Attorney-General (Hacker 1974, 24), was the leader of the mock parliament, since this gained favorable and extensive publicity regarding suffrage (Ray 1978, 39)(Hacker 1974, 24). Unlike all the other trajectories of her life, she was at her highest point as a suffragette right before her death

3.2. Where Did the Events Take Place?

Where the life-changing events took place in Emily Stowe’s life is summarized in

Table 2. Distances from one location to another reported in

Table 2 have been calculated by the author given the information provided by references.

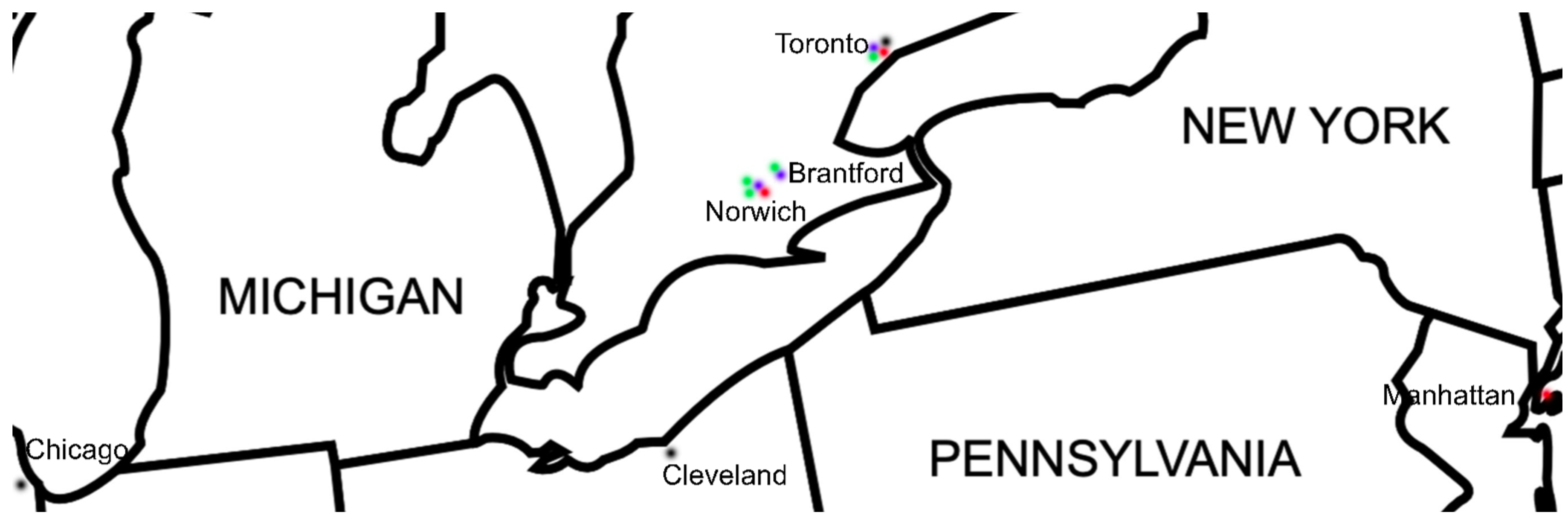

3.2.1. Where—Personal

Stowe’s birth took place in what was then Norwich Township, Upper Canada (Feldberg 1994)—the 15,000 acre farm purchased by her mother’s—the Lossing (Stagg 2003)—family (See

Figure 3 for the size and location of Norwich Township). The property was a Crown grant (Fryer 1991, 14). It should be noted that the usual allotment to heads of families in Upper Canada was 100 acres, with field officers receiving the largest amounts at 1000 acres, indicating the wealth and influence of Stowe’s family (R. Hall 2022). By the time of her marriage in Mount Pleasant (Raymond 2008a), located 10 km. southwest of Brantford where she was teaching at the time, Upper Canada had become Canada West (Foot 2019). Stowe moved back with her mother in Norwich for the birth of her first child (Lloyd 2022, 11:10)—although contrary information had been offered earlier regarding the birth of her first child (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 120)—while the two younger children were born in Mount Pleasant (Lloyd 2022, 11:18). Her husband’s death occurred in Toronto (Kawartha Ancestral Research Association Inc. 2023), in what was now Ontario. Stowe broke her hip at the Columbian Exposition‘s Women‘s Congress in Chicago, Illinois (Feldberg 1994), located 840 km southwest of Toronto where she was living, and where she ultimately died at 461 Spadina Ave., Toronto, at her daughter’s house (

The Globe (1844-1936) 1903). The purple dots on the map of

Figure 4 represent these locations and their relationship to each other.

3.2.2. Where—Teacher

Emily, then Jennings, although homeschool herself, began her teaching career first teaching in a school in Summerville (3.5 km west of her home) (Baros-Johnson 2004) and then in Burgessville (8.5 km northwest of her home) (Fryer 1991, 32) from 1849-1850 (Lloyd 2022, 9:18)—although one author claims she taught only in Summerville during this period (Raymond 2008a) and another states she taught at various schools in the area (Baros-Johnson 2004). Both schools were located in Norwich, therefore, they were within the boundary of the property owned by the Lossing (mother’s) family. She attended the recently built (Baros-Johnson 2004) teachers college at the Provincial Normal School for Upper Canada (Ryerson 1854) located at Gerrard and Church St., in Toronto (Fryer 1991, 33). 150 km east of Norwich and, after graduating, became the principal of what would be known as Brantford Central School (Fryer 1991, 34) (40 km east of Norwich). When she chose to take up teaching again after her husband contracted tuberculosis, she was a teacher at her next-door neighbor’s school (Fryer 1991, 38)—Nelles Academy at Mount Pleasant, where she continued to live with her children after her husband moved from home to recover (Fryer 1991, 37). On the map of

Figure 4, the green dots indicate where she was a teacher.

3.2.3. Where—Physician

Stowe apprenticed as a homeopathic physician (Raymond 2008a) in Norwich Township—the property owned by her mother’s family. To continue as a homeopath, and because she was able to gain acceptance to continue her education in applying to college for women (Hacker 1974, 20), she went to medical school at the New York Medical College in Manhattan (850 km southeast of Norwich). She became an unlicensed practitioner, moving to a number of homes in Toronto—choosing Toronto because of its size (Fryer 1991, 57). The first being at 39 Alma Terrace, Richmond Street (

The Globe 1867), and then, when Stowe needed to expand her office (Ray 1978, 23) to include her husband’s dentistry practice , at 111 Church St. (Backhouse 1991, 162) (Fryer 1991, 61)—the address appearing on her letterhead (Hogendoorn 2018). The court case regarding one of her patients to which she was acquitted took place at the County Court in Toronto. Once she became a licensed practitioner as a result of her acquittal, she initially continued her practice at 111 Church St., but later moved to 119 Church St. and then to 463 Spadina Ave., all in Toronto (Stowe 1880). The red dots on the map of

Figure 4 indicate where the events regarding her role as a physician took place.

3.2.4. Where—Suffragette

The founding of the Toronto Women’s Literary Club was inspired (Brookfield 2019) by a meeting of the American Society for the Advancement of Women (Ray 1978, 28) that Stowe attended in Cleveland, Ohio (Luke 1895, 328) (470 km southwest of Toronto, where she was living at the time). Stowe campaigned to have women admitted to medical school in Canada and was successful with the opening of the Toronto Women’s Medical College (Forster 2004, 247) at 289 Sumach St. (2.3 km east from her home on 111 Church St.) (Women’s College Hospital 2023). She became the vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association in the City Council Chamber of Toronto (Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association 1883), located only 600 m from her home. Stowe was then an addresser at the Provincial Legislature Building in Toronto (MacLeod 2021), located 2.6 km northwest of her home at 111 Church St. The founding of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association occurred at Stowe’s then home at 119 Church St. in Toronto (Cleverdon and Cook 1974, 24). Stowe became a member of the National Council of Women of Canada at the Columbian Exposition’s Women’s Congress held in Chicago, Illinois, as part of the Chicago World’s Fair (Baros-Johnson 2004), 840 km southwest of Toronto. She was leader of the mock parliament on the inequalities of Canadian women at Allan Gardens in Toronto (TIMELINE Women’s Suffrage 2023). The locations where Stowe worked as a suffragette are indicated on

Figure 4 with black dots.

3.3. Who Helped Stowe in the Events?

Who was connected with Stowe’s life-changing events is summarized in

Table 3.

3.3.1. Who—Personal

Emily Jennings was born to Hannah Lossing Howard Jennings and Solomon Jennings (an Empire Loyalist, originally from Vermont (Feldberg 1994)), part of the well-to-do Establishment of the then Upper Canada. “The Lossing and Jennings families commanded respect both north and south of the border” (Feldberg 1994). She was brought up by them as a Quaker (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004,157) being taught that men and women were equal (Feldberg 1994) (Hacker 1974, 18). She married John Stowe, Jr. (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 157) a Methodist and a carriage maker whose views coincided with Stowe’s regarding the equality of men and women (Feldberg 1994). Together, they had three children, Ann Augusta, John Howard, and Frank Jennings (Hacker 1974, 18). When John Stowe died of lung related illness, he was at home with his family (Fryer 1991,105). Emily Stowe died in the company of her children (Feldberg 1994).

3.3.2. Who—Teacher

Stowe was homeschooled by her mother (Feldberg 1994). However, she was thought the most qualified to teach by Dr. Ephraim Cook (Fryer 1991, 31), the first physician of Norwich country (Mott 1946, 40) and the superintendent of Norwich schools (Fryer 1991, 31). When she attended teachers college, the headmaster at the time was Thomas J. Robertson (Ryerson 1854), who had been hired by the founder of the teachers college as the first Superintendent of Education for the province, Egerton Ryerson, on a visit to Dublin (Fryer 1991, 32-33). Upon her graduation, Stowe was hired as principal by James Wilkes, the chair of the Brantford School Board (Fryer 1991, 32). Returning to teaching after the birth of her third child, Stowe was offered a teaching job (Fryer 1991, 38)(Ray 1978, 14) by her next door neighbor, Dr. William Waggoner Nelles to teach at the school he founded (Nelles Academy Class Photograph, Mount Pleasant, c. 1893 1893). Stowe’s sister, Cornelia, helped her look after the children and household (Baros-Johnson 2004) when she was at the Nelles academy (Ray 1978, 16). It is claimed that the Stowe’s had a “very active friendship…with Dr. William Nelles. John Stowe worshipped with him…the Nelles and Stowe children grew up together” (Hacker 1974, 19)

3.3.3. Who—Physician

In her youth, Emily Jennings was an apprentice homeopathic physician with Dr. Joseph J. Lancaster, a master homeopath—first in the province (Fryer 1991, 36)—and friend of her mother’s (Raymond 2008a). When she attended the New York Medical College for Women in New York, she was able to do so because her sister, Cornelia Lossing Jennings agreed to look after her children (Fryer 1991, 47) by moving to the Stowe home in Mount Pleasant (Lloyd 2022, 11:48). The College was directed by Dr. Clemence Lozier (Forster 2004, 246), a close associate of Susan B. Anthony (Roberts 1977, 146). Once she completed her medical training, she returned to intern, again with Dr. Joseph J. Lancaster (Fryer 1991, 47), before setting up her practice. She was acquitted in a court case concerning the death of Sarah Lovell (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879), a past patient of Stowe’s, based on the testimony of four physicians who came to her defense: Dr. Henry Wright, Dr. Charles Berryman, Dr. Uzziel Ogden, and Dr. Daniel McMichael (Backhouse 1991). The judge in the trial was Kenneth Mackenzie (Backhouse 1991, 174) (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879). It was as a result of the support offered by these doctors, representing liberal male physicians who were leaders in the profession (Duffin 1992, 884), that Stowe was able to obtain her license to practice medicine.

3.3.4. Who—Suffragette

“The first Ontario suffragists were made up of a group of predominantly white, Anglo-Protestant, educated women led by Dr. Emily Stowe” (MacLeod 2021). Inspired by Susan B. Anthony (Forster 2004, 246), together with her friend, Helen Archibald (Luke 1895, 329), Stowe founded the Toronto Women’s Literary Club, becoming a travelling lecturer (Luke 1895, 328). To enable her daughter to go to medical school in Canada, Stowe talked with Dr. Samuel Nelles (Fryer 1991, 76), head of Victoria College, and brother of Dr. William Nelles, her next door neighbor (Fryer 1991, 38). On becoming vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association to which Mrs. Donald McEwan was present, she was joined by three other vice presidents, two of them men (Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association 1883, 17). When she was an addresser regarding provincial passage of the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021), those in attendance were the members of the legislature of the time. When she became the president of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association (Baros-Johnson 2004), those witnessing the event were the other members of the association. After breaking her hip and being unable to become the president of the National Council of Women in Canada, those who were present were the members of the said council. Mary MacDonnell became president in her stead (Fryer 1991, 1). As the leader of the mock parliament on the inequalities of Canadian women, Annie O. Rutherford, then-president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, was the speaker for the event; her daughter , Dr. Augusta Stowe-Gullen, was also involved (Women in the Park 2022) as representing the honorable member for Brant (Fryer 1991, 114).

3.4. What Happened?

What happened regarding Stowe’s life-changing events is summarized in

Table 4.

3.4.1. What—Personal

Stowe was one of six surviving children (Feldberg 1994) of an Empire Loyalist family whose ancestor had purchased their 15,000 acre tract for $7,500 (Mott 1946, 11). She was attracted to her future husband, John Stowe, as he was a free thinker (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 158). Stowe resigned from teaching to be a homemaker. Her husband died at home (Fryer 1991, 105), as did she, twelve years later, at a different home (Fryer 1991, 120).

3.4.2. What—Teacher

Although equally qualified as a teacher to her male counterparts, Stowe was paid half the salary of men for the same work (Baros-Johnson 2004) (Ray 1978, 11). Her ability as a teacher was demonstrated when she easily completed the course at the teachers college in only six months (Fryer 1991, 33). She became the first woman principal (Stowe Gullen 1906, 3) (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903) in what was then Canada West (Lloyd 2022, 10:20). When she returned to teaching after having her children, she taught at the Nelles Academy, a non-denominational private boys’ school for “young gentlemen” (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 151). However, it is likely that by the time Stowe was hired the school had already become the County Grammar School, to which Dr. Nelles remained the principal (Fryer 1991, 38).

3.4.3. What—Physician

As a pre-teen, Stowe followed her mother in learning root and herb remedies (Raymond 2008a). She graduated from the Woman’s New York Medical College (Stowe Gullen 1906) in a class of nine students (Fryer 1991, 47) and became an unlicensed practicing physician as obtaining the license as of 1865 required completing the full medical course in Canada (Hamilton 2017, 1022); however, Stowe was unable to complete the course as no women were permitted to do so (Hacker 1974, 21). After her court case, in which the judge decided there was no case for the jury (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879), she became a licensed practicing physician (not, as one author claims, that she was unlicensed her entire career (Newman 2008, 5)) as she was grandfathered (Duffin 1992, 886) for her apprentice work with Dr. Joseph J. Lancaster before 1850, when she was a pre-teen. As a result of breaking her hip, she ended her career as a physician (Feldberg 1994).

3.4.4. What—Suffragette

Stowe became interested in founding and lecturing as a representative of the Toronto Women’s Literary Club as the U.S. 15th Amendment of 1870 was popularly interpreted to enfranchise women, creating societies in the U.S. that had inspired Stowe to do the same (Cleverdon and Cook 1974, 16). As a campaigner to have women admitted to medical school in Canada, Stowe was successful in having women enrolled at Victoria College (Fryer 1991, 76). She became the vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association as this was a new association open to both women and men; “The object of the Association is, to obtain for women the Municipal and Parliamentary Franchise, on the same conditions as those on which these are, or may be, granted to men” (Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association 1883, 4). Stowe became an addresser for the provincial passage of the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021) as she was personally affected by having to pay the tax for the property she owned with her husband, yet only her husband was permitted to vote (MacLeod 2021). The Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association, to which she was president, was founded primarily to work towards suffrage (Bacchi 1978, 463). Upon breaking her hip at the Columbian Exposition‘s Women‘s Congress in Chicago, she was unable to assume the duties of being president of the National Council of Women of Canada as expected and, therefore, became only a member of the Council (Fryer 1991, 110). It was in following a similar event in Winnipeg that Stowe was the leader of a mock parliament on the inequalities of Canadian women (Hacker 1974, 24).

3.5. How Did the Events Take Place?

How each of Stowe’s life-changing events happened is summarized in

Table 5.

3.5.1. How—Personal

With her birth, Emily Stowe became the eldest of six girls (Baros-Johnson 2004). She married her husband because she could count on him for “sympathy and assistance” (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 158). She had only three children because she considered she had to go to work to support her family (Roberts 1977, 146). Still, “her relatives were prosperous and well established, and she enjoyed their support during her husband’s illness” (Feldberg 1994). When her husband died, he was in the company of his family. Emily Stowe also died surrounded by her family (Feldberg 1994).

3.5.2. How—Teacher

Stowe was likely drawn to being a teacher as there was a sudden demand for teachers in the province as a result of free education being introduced in 1850 (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 158). She was able to go to teachers college because the Provincial Normal School had opened in 1847 (University of Toronto OISE 2023), six years before she enrolled. She received a first class certificate and was able to become a principal because she had completed the teachers college program (Fryer 1991, 34). She resumed teaching after having her children because a close friend of the family offered her employment at his school (Forster 2004, 245).

3.5.3. How—Physician

How it was that Stowe was able to be an apprentice homeopathic physician in her pre-teens was that the doctors she apprenticed with was a native of Norwich and an old friend of her mother’s family(Fryer 1991, 36). It was necessary for Stowe to attend medical school in the U.S. as she was denied admission at the University of Toronto because she was a woman. She could easily go to New York because of her family’s close personal ties (Feldberg 1994) and her sister’s willingness to look after her children (Roberts 1977, 146). Once Stowe completed her medical degree, she set up an unlicensed practice because her application for a license as a homeopath was too late for acceptance under the new rules for obtaining a license (Feldberg 1994). In the trial regarding the death of Sarah Lovell, Stowe was acquitted because she was not considered to have administered the abortion drugs she had prescribed (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879). After the trial, Stowe was able to become a licensed practitioner without her requesting it (Baros-Johnson 2004) because she was able to produce affidavits from respected physicians (Duffin 1992, 886) saying she was in practice before 1850—“she was admitted on the basis of her credentials and her earlier medical work as an apprentice to Dr. Joseph J. Lancaster” (Raymond 2008a). Stowe’s medical career was ended when she fell off the stage and broke her hip (Feldberg 1994).

3.5.4. How—Suffragette

Stowe became a founder and lecturer with the Toronto Women’s Literary Club (Luke 1895, 329) resulting from attending a meeting of the American Society for the Advancement of Women. How the Club operated for women was as “an association for intellectual culture, where they can secure a free interchange of thoughts and feeling upon every subject that pertains to woman’s higher education, including her moral and physical welfare”(Luke 1895, 329) permitting women a democratic liberal education (Murray, 1999, 77). Stowe herself lectured at the Club on “Women’s Sphere” and “Women in the Professions” (Baros-Johnson 2004). She was a successful campaigner regarding admission of women to medical school in Canada as a result of talking with the President of Victoria College (Baros-Johnson 2004). As the vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, it was Stowe who presented the motion that qualified women should be permitted to vote. She made an address regarding the provincial passage of the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021) by giving a presentation in front of parliament. How she became president of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association was that similar organizations were being founded at the same time throughout the world. She was only a member of the National Council of Women of Canada (Feldberg 1994) and not the president because he had just broken her hip. Stowe was the leader of the mock parliament on the inequalities of Canadian women (Hacker 1974, 24) as this event was a collaboration between the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association of which Stowe was president.

3.6. Why Did the Events Occur?

Why each of Stowe’s life-changing events occurred is summarized in

Table 6.

3.6.1. Why—Personal

Why Stowe was born to her parents is that each came from a wealthy (Spears 2017) Establishment family. She married her husband to create a home synonymous with promotion of education stating she had “outgrown all religious creeds, standing in the broad field of enquiry, a truth-seeker” (Baros-Johnson 2004)—doing so enhanced the reputation of the village of Mount Pleasant (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 158). Stowe was only able to have three children because her husband contracted tuberculosis and moved to another location to recover (whether he was treated at a sanitorium proper is unknown (Fryer 1991, 37)), living away from Stowe. Her husband died as a result of a lung weakness (Fryer 1991, 105). She herself died of “a few days’ illness” (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903).

3.6.2. Why—Teacher

Although Stowe was homeschooled herself (Baros-Johnson 2004), she as considered the most qualified person to teach in Norwich schools (Hacker 1974, 18). Why this was is that the year Stowe started teaching in 1846 the School Act of 1846 centralized administration of education (Wallin, Young, and Levin 2021, 54) in what was then Canada West, making education a right, demanding many new teachers. Stowe went to teachers college as she was rejected from Victoria College (then in Coburg) because she was a woman, but also because in 1853 Ryerson introduced a certificate for province-wide recognition of Normal School graduates (Kitchen and Petrarca 2014, 57) and this was Stowe’s first opportunity to get certification. Based on the first class honors she received from teachers college (Raymond 2008a) (Lloyd 2022, 10:08) she was hired as the first woman principal. She went back to teaching even though this was not normally possible for a married woman, a significant reason for why she was permitted to go back to teaching is the Nelles academy was a feeder school for the high school in Brantford where she had previously been principal (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 153).

3.6.3. Why—Physician

Stowe apprenticed with Dr. Lancaster as a homeopathic physician because he was the first such practitioner in Upper Canada, and because he was considered the best (Fryer 1991, 36). Why Stowe went to medical school in New York is that it was one of the few medical schools that leaned towards homeopathy (Fryer 1991, 41). Most importantly, it was an all-women school and, therefore, willing to take a female student (Jaeger and O’Byrne 2004, 159). As well, Stowe would have felt comfortable going to New York as it was home to her mother’s relatives (Feldberg 1994) (Fryer 1991, 17). Stowe was insistent on becoming a practitioner, even without a license, because she was committed to specializing in the diseases of women and children as a special calling, especially associated with "anti-sex" education which taught the young "all the consequences of the transgression" (Bacchi 1978, 471), as Stowe was said to believe in “abstinence except for procreative purposes” (Backhouse 1991, 169). In there being no reason to consider that Stowe had been guilty of attempting to procure an abortion, she was acquitted at her trial (The Globe (1844-1936) 1879). The acclaim Stowe received from the acquittal provided reason for her to become a licenses practitioner because the court case had publicly demonstrated her proficiency as a physician (Duffin 1992, 886). The death of her husband was the reason for moving her practice from 111 Church St. to smaller quarters (Ray 1978, 41). Breaking her hip gave Stowe reason to end are career as a physician (Baros-Johnson 2004).

3.6.4. Why—Suffragette

Why Stowe was able to become founder and lecturer for the Toronto Women’s Literary Club is that her husband recovered from tuberculosis and became a dentist (Fryer 1991, 61) working out of the same office as Stowe (Forster 2004, 246). She became a campaigner for the admission of women to medical school in Canada because she wanted her own daughter to go to medical school in Canada and, particularly, to become the first woman to do so (Baros-Johnson 2004) (Bacchi 1982, 577). She was able to accomplish this because of her long-standing friendship with the Nelles family emboldening her to talk with and convince Samuel Nelles, principal of Victoria College, to permit women to be admitted (Ray 1978, 31). In becoming a vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, Stowe was considered the most qualified candidate by both the women and men of her social class. Stowe was chosen to be the addresser for the provincial passages of the Married Women’s Property Act (MacLeod 2021) because, as a result of her lecture circuit, she was used to speaking in front of audiences. As well, she was a supporter of the complete economic independence of women (Bacchi 1982, 581). The passing of the act (Feldberg 1994) was also seen by the provincial legislature to be compensation for women not getting the vote at this time. As president of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association, Stowe was the guiding force (Raymond 2008a) in the name change of the association after attending a meeting of international suffragettes. Yet, unlike her American counterparts (MacLeod 2021), “Stowe adopted a patient strategy, encouraging gradual progress” (Baros-Johnson 2004) when advancing women’s rights and suffrage in her own Canada. Why she became a member of the National Council of Women of Canada even after breaking her hip because her seat was placed too close to the edge of the stage (Fryer 1991, 110) is that, although she could not be its president, she wanted to stay involved with the organization. She agreed to lead the mock parliament on the inequalities of Canadian women because she considered it appropriate to follow the lead of U.S. suffragettes in conducting such mock parliaments (Bird 1992).

4. Discussion

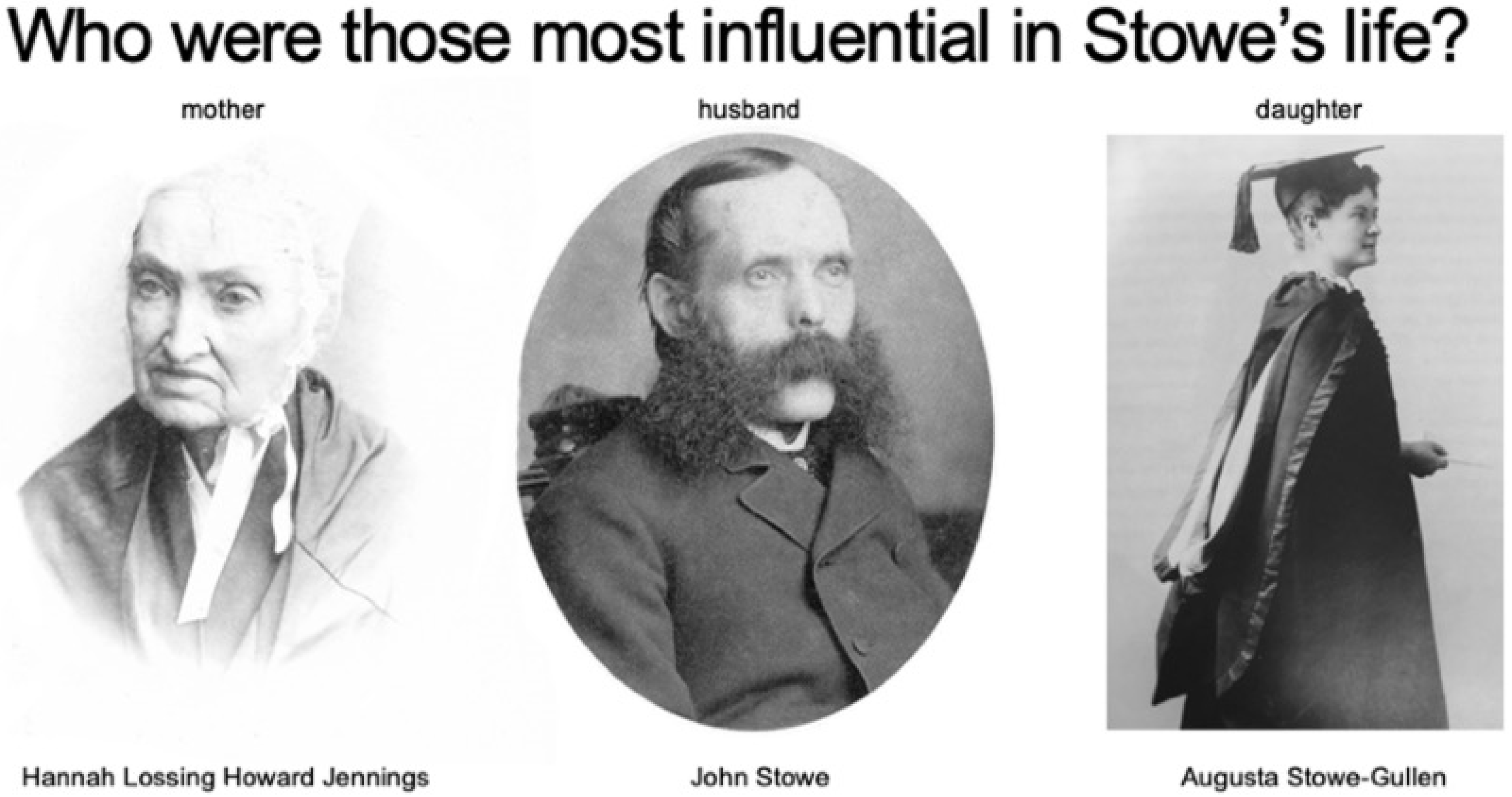

It had been noted that the method used for creating a narrative of Emily Stowe’s life has the ability to makes relationships regarding her life-changing events easier to identify, compare, and develop. What will first be examined is how this method makes identifying and comparing the life-changing events of her life easier. This will be accomplished by taking four different points in Emily Stowe’s life, representing one of each of the four aspects of her life (personal, teacher, physician, and suffragette), and comparing the when, where, who, what, how and why associated with a particular point. After this examination, how the method makes developing her narrative easier will be demonstrated by presenting in what way the three most important people in the personal aspect of her life—her mother, her husband, and her daughter—affected the three other aspects of teacher, physician, and suffragette. To this extent, her mother had the greatest impact on her during her youth in relation to her becoming at teacher; her husband can be considered the stimulus of Stowe becoming a physician; while her daughter can be regarded as the catalyst for her work as a suffragette. In this way, the story of Emily Stowe’s life can be recounted from these three different perspectives, representing the various stages of her life work.

4.1. Identifying and Comparing Life-Changing Events of Emily Stowe

Three distinct life-changing events will be considered of the twenty-two that have been recognized to identify and compare each of the questions that were answered related to these events in asking when, where, who, what, how, and why. The results will come from reading off the relevant entries from each of

Table 1 through to

Table 6.

4.1.1. School Teacher

From 1863-1865, when Emily Stowe was thirty-two to thirty-four years old, she was a teacher at the Nelles Academy at Mount Pleasant, Canada West, located across from her house (Hacker 1974, 19). It was Dr. William Waggoner Nelles, founder of the school (Fryer 1991,38), who hired her. During the time she taught at the school she had the double load of teaching and being a homemaker for her children, as her husbanded lived away from home after contracting tuberculosis (Hacker 1974, 20). She was able to gain this employment because Nelles was a next door neighbor and friend of the family (Hacker 1974, 19). Why she took the position was that she knew tuberculosis was contagious, so her husband was sent away as to not infect the children.

4.1.2. Acquittee of Court Case

In September 1879, when Stowe was forty-eight, in the County Court of Toronto, she was a defendant in the case of the sudden death of a patient of hers, Sarah Lovell, after this pregnant nineteen year old wanted Stowe to provide her with medicine to procure and abortion (Backhouse 1991). Stowe gave her an ineffective dose to go away. Based on the testimony of four expert witnesses who came to Stowe’s defense—Dr. Henry Wright, Dr. Charles Berryman, Dr. Uzziel Ogden. And Dr. Daniel McMichael—Judge Kenneth Mackenzie acquitted Stowe of the charges as she was found not to have provided the means to procure and abortion (Duffin 1992).

4.1.3. Campaigner, Admission of Women to Canadian Medical Schools

From 1879-83, when Stowe was forty-eight to fifty-two, she sought to have women admitted to the Toronto School of Medicine. To do so, she talked with Dr. Samuel Nelles, who headed the School, whom she knew as he was the brother of Dr. Wm. Nelles, her next door neighbor and the person who had hired her as a teacher at the Nelles academy, twelve years earlier (Fryer 1991, 38). As a result of her actions in talking with Samuel Nelles, women were then able to enroll as medical students at the Toronto School of Medicine through Victoria College. Why she undertook to have women admitted is that she wanted her daughter to go to medical school in Canada (Baros-Johnson 2004) (Bacchi 1982, 577).

4.1.4. Broken Hip

When Stowe was sixty-two, in 1893, she attended the Columbian Exposition’s Women’s Congress in Chicago (Baros-Johnson 2004), Illinois for the purpose of electing the executive for the National Council of Women of Canada (Feldberg 1994). Those in attendance expected her to be elected president. However, because her seat on the stage was placed too close to the edge (Fryer 1991, 110), and she was unfamiliar with her surroundings she fell off the stage and broke her hip (Feldberg 1994). As a result, she could not be elected president and Mary MacDonnell was elected in her stead (Fryer 1991, 110). However, she remained a member of the Council even after breaking her hip, and was able to attend the first annual meeting of the organization (Fryer 1991, 111).

4.2. Developing Three Consecutive Narratives of Emily Stowe’s Life

In regards to developing the narrative of Emily Stowe, the following represent the three different narratives that can be produced by considering Stowe’s personal life in relation to the other three aspects of her life.

Figure 5 represents those people who were the catalysts for these three separate narratives as the three most important people in Stowe’s life.

4.2.1. Mother’s Daughter as a Teacher

Emily Howard Jennings, was born May 1, 1831 to an Establishment family in Norwich, Upper Canada—a 15,000 acre property (a little larger than the size of Manhattan) originally purchased by Stowe’s maternal grandfather, Peter Lossing. A gifted learner and the eldest of 6 girls, she was homeschooled by her Quaker mother (a homeopathic practitioner) to consider women equal to men in their ability to learn. Respect for her mother led her to apprentice in homeopathy as a pre-teen with the homeopathic physician most respected by her mother. Although homeschooled, she was considered most able to teach by school trustees at schools in her area and did so for seven years. She intended to pursue higher learning but was rejected by Victoria College because she was a woman. After attending the new Ontario teachers college in Toronto, she was hired as principal of a school in Brantford, demonstrating her abilities. She was the first woman principal in Canada West (now Ontario). Although resentful of her low pay compared to that of men, she was only willing to disrupt the status quo through her intelligence, not through public demonstrations contrary to her social status. Viewing women as equal to men intellectually as her mother had taught her, she still considered women to have a special role with respect to children. In this way, she was more than willing to quit her teaching career to marry and raise a family with a man who supported the values taught to her by her mother of women’s intellectual equality and their special role a homemakers.

4.2.2. Husband’s Wife as a Physician

Abandoning organized religion, Emily Jennings married John Stowe Jr., who lived in Mount Pleasant, a town immediately south of Brantford where she was principal. They had three children before her husband contracted tuberculosis. With her husband no longer at home, Stowe was forced to start teaching again, albeit beneath her previous rank. Looking for a more fitting occupation to provide for her family, Stowe turned to her knowledge of homeopathy. Again, unable to be admitted in Canada as a woman, she enrolled in a Manhattan medical school, as it supported both women and homeopathy. Moving to Toronto after graduation, she was the first white women to openly practice medicine in Canada, although she remained unlicensed. Once he was well, her husband came to Toronto and set himself up as a dentist working along-side her at 111 Church St. in Toronto. As a result, she was then able to focus her attention on educating Ontario citizens regarding the intellectual equality of women creating the Women’s Literary Society of Toronto. Her husbands’ death caused her to move to a smaller premise but also provided her with the time to take up additional commitments regarding women’s enfranchisement

4.2.3. Daughter’s Mother as a Suffragette

To permit her daughter to attend, Stowe worked to gain women access to the Toronto Medical School. Her success, and the continuing support of the Establishment, gave her reason to publicly work as a suffragette, first as vice president of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, then president of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association. In these leadership roles she convinced the Province to pass the Marriage Women’s Property Rights Act, giving women property ownership. However, her efforts were insufficient for women to gain the vote. Unlike her American counterparts, who were willing to be arrested for their beliefs, she limited her action to bring suffrage to intelligent discussion alone. A member of the National Council of Women of Canada after she broke her hip in 1893 immediately before the Chicago event electing officers, she did not become its president as expected. Nevertheless, her accident did not slow down her resolve to concentrate on enfranchisement. Three years later, she was the leader of a mock parliament regarding the inequalities of Canadian women where her daughter represented the honorable member for Brant. She died at home of an illness five years later, April 30, 1903, with her family. Her daughter then continued her suffragette work as president of the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association in her place.

4.3. Limitations

The strengths of this method of constructing Emily Stowe’s narrative have been outlined as making it easier to identify, compare, and develop the life-changing events that have been examined. Identifying and comparing four of her life-changing events has been presented, as well as developing three different consecutive personal narratives based on the three aspects of her life that represented her work outside the home. Although these are the strengths, there are weaknesses to the use of this method and to investigating Emily Stowe’s life-changing events in general. These limitations will be divided in two different sections: (1) those that concern the method used to investigate Stowe’s twenty-two life changing events, and (2) limitations that result from records that can no longer be accessed.

4.3.1. Regarding the Method

The limitations regarding the method were implied in the Introduction when it was mentioned that this method, unlike other forms of narrative research, does not place the life of a subject within a particular strategy (Argyres et al. 2020), mindset (Dweck and Yeager 2019), epoch (Mignolo 2020), or in relation to other history-makers (Berger 2023). Furthermore, it does not interpret Stowe’s life from the perspective of current social issues (J. Hall, Gaved, and Sargent 2021). As other biographers of Emily Stowe have concentrated on developing her history from these type of considerations, this limitation, although recognized, is considered acceptable for the purpose of this study.

In accepting this limitation, topics that have been the concentration of past historians in accessing Stowe’s life have not been mentioned, as they did not have a life-changing effect on her. Two issues are examples. The first is the trial of Emily Stowe regarding Sarah Lovell’s death. This has been the focus of two separate publications by academics (Backhouse 1991),(Duffin 1992). Another issue that is not mentioned in this account is the relationship between Dr. Emily Stowe and Dr. Jennie Kidd [Gowanlock]Trout—the first female licensed physician in Canada. Other writers on Stowe have inferred there was some personal rivalry between these two women that was significant in relation to the establishment of two different medical schools accepting women (Dembski 2005)(Fryer 1991), although Trout , ten years younger than Stowe, had even lived with the Stowe and her family at their 111 (Backhouse 1991) Church St. home (Raymond 2008b). If there was such rivalry, it had no impact in changing the life of Emily Stowe, as she would have done nothing differently had Trout not come to her attention. There were, as argued, only three truly important people in Stowe’s life that were the cause of its changes: her mother, her husband, and her eldest daughter.

4.3.2. Concerning Inaccessible Records

In considering limitations to this work, it should also be noted that whether what is common knowledge about Emily Stowe being the first female principal in Canada is true is unclear. It has been stated (Stowe Gullen 1906) and has been restated (Davidson 2014, 12)(Fryer 1991, 31)(Raymond 2008a)), without a reference provided by the authors making the claim, that Emily Stowe was the principal of the Brantford Central Public School from 1854-1856. However, in a 1920 book on Brantford, the following quotation is found, ”In writing in 1891, his reminiscences with reference to this community, Dr. Kelly [Michael J.] said: I first saw Brantford some time in the autumn of 1855. From Paris, the journey was made by stage. I had received the appointment of principal of the Central School for the town. I was, I suppose, the youngest principal the school had ever had, and spent a very pleasant, if a busy time, within the walls of the old building. The teachers then under me were, Mr. E. Nugent, Miss Morrison, now Mrs. Cummings of Hamilton; Miss Jennings, later Mrs. (Dr.) Stowe, of Toronto…”(Reville 1920, 119). If this information is correct then Dr. Kelly, rather than Emily Stowe, was the principal of Brantford Central and Emily Stowe was a teacher under his leadership. Further information from the Brantford library confirms this position and date for Michael J. Kelly as principal, “In 1855 he came to Brantford as principal of Central School, the youngest one in Brantford at the time”(Early Brantford/Brant County Doctors, n.d.). This information was stated again in a later history of Brantford (Early Brantford/Brant County Doctors, n.d.), nevertheless, could not be confirmed by the current principal of the Brantford Central School (Atanas 2023) as records had not been kept on past principals to that time period. At least one author has equivocated on the matter by stating that Stowe worked for the Brantford school board, “perhaps the first woman appointed principal of a public school in Canada West” (Baros-Johnson 2004). A 1983 paper written by a Brantford historian states that the principal of Brantford Central was Sampson P. Robbins from 1853 to 1855 (Saldarelli 1983, 4), providing evidence that Stowe also was not principal before 1855.

An additional problem regarding records is that some records that were accessible in the past are no longer searchable on the internet as there has been some type of reorganization of the Library and Archives of Canada that leaves past links to references creating an error. As an example, in 2017 the following quotation was accessible, “Dr. Emily Howard Stowe was a pioneering Canadian physician and suffragette. She was not only the first Canadian woman to practise medicine in Canada, but she was also a lifelong champion of women's rights. Her tireless campaign to provide women with access to medical schools led to the organization of the women's movement in Canada and to the foundation of a medical college for women.” It had the following reference: “Dr. Emily Howard Stowe, ” Library and Archives Canada. 21 July 2008,

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/physicians/030002-2500-e.html. This link now results in an “HTTP Error 404 - Not Found.” Furthermore, the quotation has not been re-archived and is now inaccessible. This is an important limitation as it means the records archived by the Canadian government regarding Emily Stowe are fewer than in the past, presenting an additional limitation for Stowe scholars.

What is also a limitation is when the accounts of Emily Stowe’s life don’t provide sufficient detail. An example is why it was that Stowe started working as a teacher when her husband contracted tuberculosis. Historians who have written on the matter have stated that it was to support her family (Baros-Johnson 2004)(Hacker 1974, 20). However, Stowe came from a wealthy, upper class family (Spears 2017), as evidenced by the land owned by her family and the connections she had. If she had not wanted to work, her family’s circumstances would have been maintained. In using the question-asking process that was engaged from this assessment, it seems more likely that Stowe started working as a teacher because her next door neighbor owned a school and the school was in need of a teacher. Stowe likely started teaching both to help a neighbor and for the intellectual challenge. What remains unclear is who looked after Stowe’s young children when she was working. Although her sister, Cornelia, is known to have cared for Stowe’s children when she later went to New York for medical school (Fryer 1991, 47), Stowe and her children lived in their Mount Pleasant home while she was a teacher. It is thought that Cornelia may have moved to the Stowe house (Lloyd 2022, 11:48). Alternatively, perhaps the Nelles family returned the favor and Mrs. Nelles stayed with Stowe’s young children as she taught. Nevertheless, records are unavailable to confirm who actually cared for Stowes children while she taught.

Adding to the difficulties in knowing the facts regarding Emily Stowe’s life is that her daughter, Dr. Augusta Stowe-Gullen, was an early promoter of the type of acclaim her mother should receive in posterity, and this influenced the account of academic writers on Stowe to follow (Hamilton 2017, 1023). Her influence has been confirmed in the Introduction to H. M. Ridley’s 1965 synopsis of women suffrage in Canada where the author states she is indebted to Stowe-Gullen because “without the records preserved by her,…I could not have written this book” (Ridley 1965) It was in a brief history of the Ontario Medical College for Women that Stowe-Gullen sought to design the mystique of her mother, “By temperament, Dr. Stowe was pre-eminently, a pioneer, and reformer; not alone in teaching and medicine, but in all moral and social reforms; her great courage, and fortitude, amidst all discouragements, was truly remarkable; failure in any project impossible, for to her the meaning of the word was unknown. Ever ready.to espouse any cause, no matter how unpopular, if that cause were characterized by justice and right. A woman, who lived at a time when but few opportunities presented for women, and who passed her life in a constant endeavor to better conditions for .all oppressed classes; but who stood unswervingly, for freer and larger opportunities for women, as her efforts in opening Toronto University to women will testify. One, who found a world to conquer and who left the world better for her having lived; a truly great reformer” (Stowe Gullen 1906, 3-4).

In considering the background of Emily Stowe, academic writers have categorized Stowe as part of the group of suffragists drawn from the Anglo-Saxon Protestant middle classes” (Bacchi 1978). Although she was part of this group to some extent, by characterizing Stowe as middle class in this array, authors like Bacchi have misrepresented Stowe. Although she chose to be both a teacher and physician—representing middle class professions—as a member of the Establishment, her background was upper class (Spears 2017). Her ancestor, Peter Lossing, passed down through Stowe’s mother’s family the 15,000 acres he had purchased of Canada West at fifty cents an acre (Norwich and District and Museum and Archives 2023), known as Norwich (Stagg 2003). This is just over the size of Manhattan at 14,478 acres (Wong 2002). Furthermore, in not recognizing Stowe as a member of the upper class, the importance of her connections in paving the way for her accomplishments has been missed in reports of her life. In that these connections have not been recognized previously a limitation was created in assessing her life.

The final problem with records is when versions conflict regarding what happened in Emily Stowe’s life and there is now no way to confirm what is correct. Two examples are provided by authors who have other facts than those coinciding with the official story (there is one account of Emily Stowe that has most of its points in conflict with the official story and will not be mentioned here for that reason (Davidson 2014, 12-14)).

The first example is where Emily Stowe died. Most official accounts relate that she died in Toronto. However, there is one dictionary entry that states she died in Muskoka, north of Toronto (Stowe, Emily Howard (1831-1903) 2019). According to one author, Stowe listed her permanent address as Muskoka in the Ontario Medical Directory after 1898 (Fryer 1991, 117). The Stowe family did have a cottage on an island in Lake Joseph (Micklethwaite 1887). It is 196 km from what was Stowe’s home at 463 Spadina Ave. in Toronto to the Lake Joseph shore (confirmed from Google Maps (Google Maps 2023). From there, the family would have had to have taken a boat to their island. It is possible that Emily Stowe died at her family cottage. However, supposedly, she was ill a few days before her death, and died on April 30 (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903). Given that the Muskoka lakes freeze over in the winter (Taylor 2023), it is unlikely that her family would have been at the cottage if no boat access was available to the mainland. Still, a letter she wrote to her aunt in 1990 stated, “I go to Muskoka in the latter part of April” (Stowe 1900); consequently, she may have died at her cottage. Her death notice also states that after she broke her hip she spent “most of her time at her island home in Muskoka” (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903). It is no longer possible to confirm where exactly Emily Stowe died. Yet, one author provides information that may clear up the difficulty: “As a widow, Emily listed her address as her summer residence in Muskoka lake region north of Toronto, but stayed most of the year with her son Frank’s family in the city” (Baros-Johnson 2004).

A second example is that official accounts state that Emily Stowe attended the New York Medical College for Women in Manhattan from 1865 to 1867 (Baros-Johnson 2004) (Feldberg 1994) (Hacker 1974)(Raymond 2008a). However, there are contradictions to this official account. A letter of condolence from Susan B. Anthony to Stowe’s daughter, August Stowe-Gullen, upon learning of the death of Emily Stowe—written 25 May 1903—states, “How well I remember her way back at Dr. Loziers in 1867 and 1868” (Anthony 1903). By the end of 1867 and continuing into 1868, Stowe was recorded to have started her medical practice in Toronto (Baros-Johnson 2004), and no longer be in the charge of Dr. Loziers at the Medical College. Either Susan B. Anthony is mis-remembering, or the official accounts of Stowe’s life are incorrect. The 1965 work by Ridley, based on the writing of Stowe’s daughter, also states, “in 1868 Mrs. Stowe graduated from this school” (H. M. Ridley 1965, 4). As well, based on information provided by Stowe-Gullen, upon Stowe’s death, it was reported she graduated from the New York Medical College for Women in 1868 (The Globe (1844-1936) 1903). Again, it is no longer possible to confirm the correct dates, but these sources agreeing with the 1868 date make it more likely that the official account may be incorrect.

5. Conclusions

The official story of Emily Howard Jennings Stowe is well-known: “The first female public-school principal in Ontario, the first Canadian woman openly to practise medicine, and a founding member of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association, Emily Howard Jennings ranks as a true pioneer” (Feldberg 1994). Although it has been stated that Stowe, “considered the ‘home circle’ too narrow and too confining to absorb all of a woman’s capabilities” (Bacchi 1982, 577), this official story does not reflect what has been noted as Stowe’s guiding philosophy: “I believe homemaking, of all occupations that fall to woman’s lot, the one most important and far reaching in its effects on humanity”(Fryer 1991, 35) (Ray 1978, 14). Stowe was primarily concerned with improving the role of women as homemakers, and “affirmed the sanctity and value of women’s work within the home. She insisted repeatedly that their role as mothers gives women a measure of responsibility for the human race which even they do not fully appreciate” (Feldberg 1994). Yet, the official story of Emily Stowe portrays her instead as a fighter and champion, even a radical (Roberts 1977, 146).

The narrative of Emily Stowe generated from asking six different types of questions and organizing them into four separate aspects, as has been done in this study, shows her as a fighter and champion only to the extent considered appropriate by her social class, guiding philosophy, and when she was encouraged by important people in her life to take on these roles by their ideas, and circumstances. “Stowe adopted a patient strategy, encouraging gradual progress” (Baros-Johnson 2004). Primarily, she was extremely bright, dedicated to learning, and intellectually competitive. Consequently, without the convictions and needs of her family and social class to encourage her to act otherwise, she valued an academic approach to life focused on homemaking rather than becoming, as she was, a (subdued) fighter and champion. As such, the narrative method presented has discovered a perspective regarding the life-changing events of Emily Stowe that previously remained unrecognized, presenting future scholars with both a new method for analysis and additional results for interpreting the events of her life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvesson, Mats, and Katja Einola. 2019. Warning for Excessive Positivity: Authentic Leadership and Other Traps in Leadership Studies. The Leadership Quarterly 30 (4): 383–95. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, Susan B. 1903. Letter from Susan B. Anthony to Augusta Stowe-Gullen, May 25, 1903, May 25, 1903. S729_1.2. Wilfrid Laurier University Archives & Special Collections. https://images.ourontario.ca/Laurier/details.asp?ID=2740546&dis=dm.

- Argyres, Nicholas S., Alfredo De Massis, Nicolai J. Foss, Federico Frattini, Geoffrey Jones, and Brian S. Silverman. 2020. History-informed Strategy Research: The Promise of History and Historical Research Methods in Advancing Strategy Scholarship. Strategic Management Journal 41 (3): 343–68. [CrossRef]

- Atanas, Dina. 2023. Email to Principal Sent from the GEDSB Website, November 16, 2023. https://outlook.office.com/mail/id/AAQkADcxYTQ4ZDM3LTUwOGMtNDk2My04NjliLTA3MGFmMmQ3YmEwOAAQAISjDvqAFNJNl7dsLfH3SjQ%3D.

-

Augusta Stowe-Gullen, M.D. 1883. 2009.07 P55. Victoria University Photograph Collection. https://archival-photos.vicu.utoronto.ca/index.php?all=Augusta+Stowe-Gullen&title=&fonds=&acc=&item=&date=&subject=&submit=Search.

- Bacchi, Carol. 1978. Race Regeneration and Social Purity. A Study of the Social Attitudes of Canada’s English-Speaking Suffragists. Histoire Sociale/Social History 11 (22).

- ———. 1982. “FIRST WAVE” FEMINISM IN CANADA: THE IDEAS OF THE ENGLISH-CANADIAN SUFFRAGISTS, 1877-1918. Women’s Studies International Forum 5 (6): 575–83.

- Backhouse, Constance B. 1991. The Celebrated Abortion Trial of Dr. Emily Stowe, Toronto, 1879. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 8 (2): 159–87. [CrossRef]

- Baros-Johnson, Irene. 2004. Stowe, Emily. In Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography. https://www.uudb.org/stowe-emily/.

- Berger, Stefan. 2023. HISTORY MAKING AND ETHICS—AN INTEGRAL RELATIONSHIP? History and Theory 62 (1): 161–73. [CrossRef]

- Bird, Kym. 1992. Performing Politics: Propaganda, Parody and a Women’ Parliament. Theatre Research in Canada 13 (1 & 2). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/7253/8312. [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, Tarah. 2019. Women’s Suffrage in Ontario. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/womens-suffrage-in-ontario.

- Burton, David. 2019. Demographic Research: The Big Picture in Research. Art Education 72 (1): 46–49. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, John C., and Allan G. Hill. 2023. Introduction: Recent Developments Using Micro-Approaches to Demographic Research. In Micro-Approaches to Demographic Research, by John Caldwell, Allan Hill, and Valerie J. Hull, 1st ed., 1–9. London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association. 1883. Constitution and Rules of the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association : Inaugurated at a Public Conversazione Held in the City Council Chamber of Toronto on 9th March, 1883. Emily Stowe and Augusta Stowe-Gullen Collection. Toronto, Ont.: Bingham & Weber. https://images.ourontario.ca/Laurier/2742130/data.

- Cazalet, Sylvain. 2001. Dr Emily Howard Jennings STOWE (1831-1903). PHOTOTHÈQUE HOMÉOPATHIQUE Présentée Par Homéopathe International (blog). 2001. http://www.homeoint.org/photo/s2/stowe.htm.

- Cleverdon, Catherine L., and Ramsay Cook. 1974. The Woman Suffrage Movement in Canada: Second Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Davidson, Jonathan R. T. 2014. A Century of Homeopaths: Their Influence on Medicine and Health. New York: Springer. [CrossRef]

- De Fina, Anna. 2021. Doing Narrative Analysis from a Narratives-as-Practices Perspective. Narrative Inquiry 31 (1): 49–71. [CrossRef]

- Dembski, Peter E. Paul. 2005. GOWANLOCK, JENNY KIDD (Trout). In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 1921st–1930th ed. Vol. 15. University of Toronto/Université Laval. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gowanlock_jenny_kidd_15E.html.

- Duffin, J. 1992. The Death of Sarah Lovell and the Constrained Feminism of Emily Stowe. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne 146 (6): 881–88.

- Dweck, Carol S., and David S. Yeager. 2019. Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science 14 (3): 481–96. [CrossRef]

- Early Brantford/Brant County Doctors. n.d. Brantford Library. https://history-api.brantfordlibrary.ca/Document/View/416750a3-2569-4849-8513-da3b3753aec2.

- Emily Howard Jennings Stowe, M.D. 1867 (1831-1903). 2022. New York Medical College. History (blog). 2022. https://www.nymc.edu/about-nymc/history/college-for-women/emily-howard-jennings-stowe/.

- Feldberg, Gina. 1994. JENNINGS, EMILY HOWARD (Stowe). In Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 13. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jennings_emily_howard_13E.html.

- Foot, Richard. 2019. Canada West. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canada-west.

- Forster, Merna. 2004. 100 Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces. Toronto: Dundurn Group.

- Fryer, Mary Beacock. 1991. Emily Stowe: Doctor and Suffragist. Toronto: Hannah Institute and Dundurn Press.

- Google Maps. 2023. https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Lake+Joseph,+Ontario/463+Spadina+Ave.,+Toronto,+ON/@44.3978282,-80.8761459,8z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m13!4m12!1m5!1m1!1s0x4d2af7fd41727137:0xf73fcc45010d9622!2m2!1d-79.7385157!2d45.1719094!1m5!1m1!1s0x882b34c055fbcf21:0x861d8629718debce!2m2!1d-79.3999084!2d43.6584229?entry=ttu.