Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

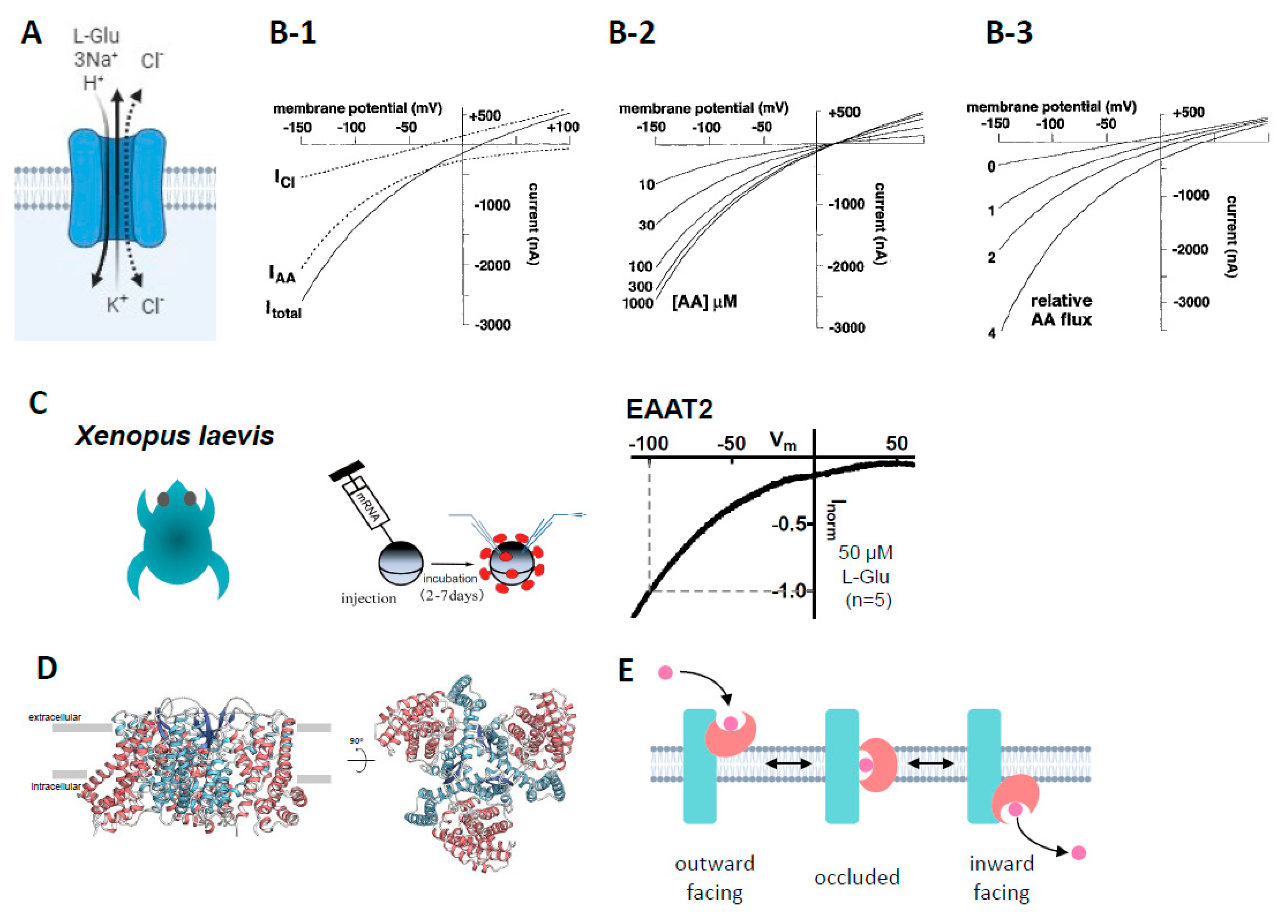

1. Basic background on EAAT2 and other L-glutamate transporters in the central nervous system

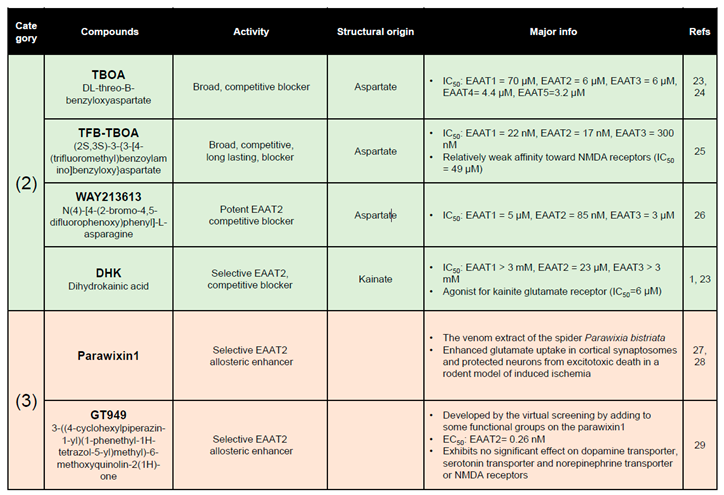

2. EAAT2 pharmacology

3. Reasons to choose Xenopus oocytes for the study of EAAT2

3.1. Advantages of Xenopus oocytes that overexpress EAAT2

3.2. Measurement of the activity of EAAT2 expressed in Xenopus oocytes

3.3. Application of molecular biological techniques to Xenopus oocytes

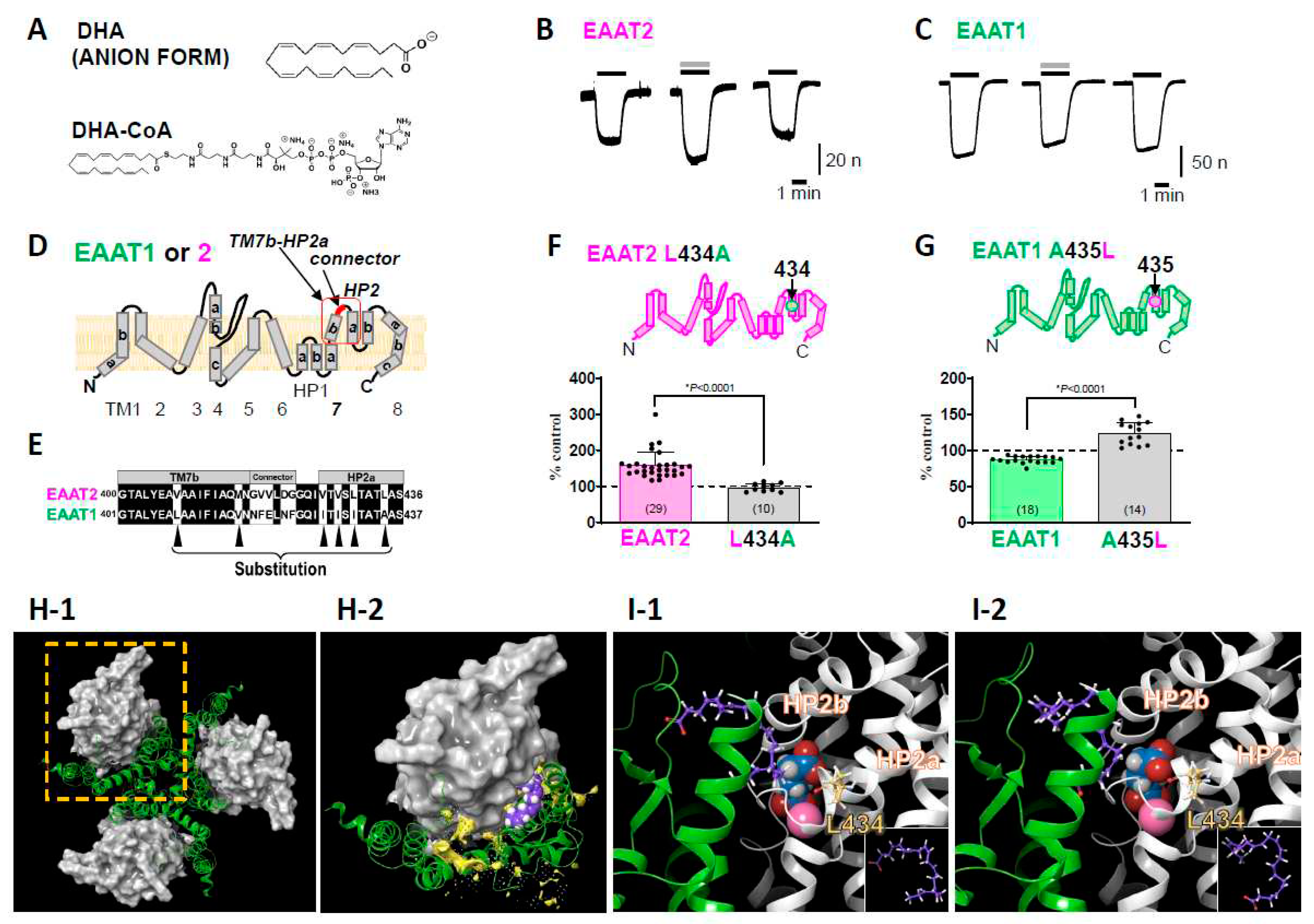

4. New findings about the interactions between PUFAs and EAAT2 obtained with Xenopus oocyte experiments

5. New insights suggested by the interactions between DHA and L-Glu transporters

5.1. Some PUFAs modulate EAATs as allosteric modulators

5.2. Physiological significance: The potential of DHA as a neurotransmission modulator

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| EAAT | excitatory amino acid transporter |

| HP | helical hairpin |

| IFS | inward facing state |

| iPLA2 | Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 |

| IV relation | current-voltage relation |

| L-Asp | aspartate |

| L-Glu | glutamate |

| OFS | outward facing state |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| SCAM | substituted cysteine accessibility method |

| TEVC | two-electrode whole cell voltage clamp |

| TM | transmembrane |

References

- Arriza, J.L.; Fairman, W.A.; Wadiche, J.I.; Murdoch, G.H.; Kavanaugh, M.P.; Amara, S.G. Functional comparisons of three glutamate transporter subtypes cloned from human motor cortex. J Neurosci 1994, 14, 5559–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, Y.; Hediger, M.A. Primary structure and functional characterization of a high-affinity glutamate transporter. Nature 1992, 360, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairman, W.A.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Arriza, J.L.; Kavanaugh, M.P.; Amara, S.G. An excitatory amino-acid transporter with properties of a ligand-gated chloride channel. Nature 1995, 375, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriza, J.L.; Eliasof, S.; Kavanaugh, M.P.; Amara, S.G. Excitatory amino acid transporter 5, a retinal glutamate transporter coupled to a chloride conductance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94, 4155–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Watase, K.; Manabe, T.; Yamada, K.; Watanabe, M.; Takahashi, K.; Iwama, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Ichihara, N.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science 1997, 276, 1699–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelis, E.K. Molecular biology of glutamate receptors in the central nervous system and their role in excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and aging. Progress in neurobiology 1998, 54, 369–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennerick, S.; Dhond, R.P.; Benz, A.; Xu, W.; Rothstein, J.D.; Danbolt, N.C.; Isenberg, K.E.; Zorumski, C.F. Neuronal expression of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 in hippocampal microcultures. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 4490–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerangue, N.; Kavanaugh, M.P. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature 1996, 383, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, M.A.; Jahr, C.E. Extracellular glutamate concentration in hippocampal slice. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 9736–9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.M.; Koo, J.C.; Antflick, J.E.; Ahmed, S.M.; Angers, S.; Hampson, D.R. Glutamate transporter coupling to Na,K-ATPase. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 8143–8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, J.; Fujimori, K.; Miura, M.; Suzuki, T.; Sekino, Y.; Sato, K. L-glutamate released from activated microglia downregulates astrocytic L-glutamate transporter expression in neuroinflammation: the ‘collusion’ hypothesis for increased extracellular L-glutamate concentration in neuroinflammation. Journal of neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Van Kammen, M.; Levey, A.I.; Martin, L.J.; Kuncl, R.W. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Annals of neurology 1995, 38, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, J.; Vogel, S.; Volkmer, H.; Breitmeyer, R. Human iPSC-Derived Glia as a Tool for Neuropsychiatric Research and Drug Development. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilton, D.K.; Stevens, B. The contribution of glial cells to Huntington’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiology of disease 2020, 143, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, V.J.; Rushton, D.J.; Tom, C.M.; Allen, N.D.; Kemp, P.J.; Svendsen, C.N.; Mattis, V.B. Huntington’s Disease Patient-Derived Astrocytes Display Electrophysiological Impairments and Reduced Neuronal Support. Frontiers in neuroscience 2019, 13, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyzack, G.; Lakatos, A.; Patani, R. Human Stem Cell-Derived Astrocytes: Specification and Relevance for Neurological Disorders. Current stem cell reports 2016, 2, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinoi, E.; Takarada, T.; Tsuchihashi, Y.; Yoneda, Y. Glutamate transporters as drug targets. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 2005, 4, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yee, S.W.; Kim, R.B.; Giacomini, K.M. SLC transporters as therapeutic targets: emerging opportunities. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2015, 14, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.W.; Gallo, L.; Jadhav, A.; Hawkins, R.; Parker, C.G. The Druggability of Solute Carriers. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2020, 63, 3834–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, L.; Erichsen, M.N.; Jensen, A.A. Excitatory amino acid transporters as potential drug targets. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2009, 13, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, R.J.; Esslinger, C.S. The excitatory amino acid transporters: pharmacological insights on substrate and inhibitor specificity of the EAAT subtypes. Pharmacol Ther 2005, 107, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Ryan, R.M. Mechanisms of glutamate transport. Physiological reviews 2013, 93, 1621–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, K.; Lebrun, B.; Yasuda-Kamatani, Y.; Sakaitani, M.; Shigeri, Y.; Yumoto, N.; Nakajima, T. DL-threo-beta-benzyloxyaspartate, a potent blocker of excitatory amino acid transporters. Mol Pharmacol 1998, 53, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeri, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Yasuda-Kamatani, Y.; Seal, R.P.; Yumoto, N.; Nakajima, T.; Amara, S.G. Effects of threo-beta-hydroxyaspartate derivatives on excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT4 and EAAT5). Journal of neurochemistry 2001, 79, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimamoto, K.; Sakai, R.; Takaoka, K.; Yumoto, N.; Nakajima, T.; Amara, S.G.; Shigeri, Y. Characterization of novel L-threo-beta-benzyloxyaspartate derivatives, potent blockers of the glutamate transporters. Mol Pharmacol 2004, 65, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, J.; McIlvain, H.B.; Carrick, T.A.; Jow, B.; Lu, Q.; Kowal, D.; Lin, S.; Greenfield, A.; Grosanu, C.; Fan, K.; et al. Characterization of novel aryl-ether, biaryl, and fluorene aspartic acid and diaminopropionic acid analogs as potent inhibitors of the high-affinity glutamate transporter EAAT2. Mol Pharmacol 2005, 68, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.C.; de Oliveira Beleboni, R.; Wojewodzic, M.W.; Ferreira Dos Santos, W.; Coutinho-Netto, J.; Grutle, N.J.; Watts, S.D.; Danbolt, N.C.; Amara, S.G. Enhancing glutamate transport: mechanism of action of Parawixin1, a neuroprotective compound from Parawixia bistriata spider venom. Mol Pharmacol 2007, 72, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.C.; Guizzo, R.; de Oliveira Beleboni, R.; Meirelles, E.S.A.R.; Coimbra, N.C.; Amara, S.G.; dos Santos, W.F.; Coutinho-Netto, J. Purification of a neuroprotective component of Parawixia bistriata spider venom that enhances glutamate uptake. British journal of pharmacology 2003, 139, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortagere, S.; Mortensen, O.V.; Xia, J.; Lester, W.; Fang, Y.; Srikanth, Y.; Salvino, J.M.; Fontana, A.C.K. Identification of Novel Allosteric Modulators of Glutamate Transporter EAAT2. ACS chemical neuroscience 2018, 9, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; Patel, S.; Regan, M.R.; Haenggeli, C.; Huang, Y.H.; Bergles, D.E.; Jin, L.; Dykes Hoberg, M.; Vidensky, S.; Chung, D.S.; et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature 2005, 433, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudkowicz, M.E.; Titus, S.; Kearney, M.; Yu, H.; Sherman, A.; Schoenfeld, D.; Hayden, D.; Shui, A.; Brooks, B.; Conwit, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of ceftriaxone for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a multi-stage, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology 2014, 13, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehre, K.P.; Levy, L.M.; Ottersen, O.P.; Storm-Mathisen, J.; Danbolt, N.C. Differential expression of two glial glutamate transporters in the rat brain: quantitative and immunocytochemical observations. J Neurosci 1995, 15, 1835–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugeto, O.; Ullensvang, K.; Levy, L.M.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Honoré, T.; Nielsen, M.; Lehre, K.P.; Danbolt, N.C. Brain glutamate transporter proteins form homomultimers. The Journal of biological chemistry 1996, 271, 27715–27722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Matsuki, N.; Ohno, Y.; Nakazawa, K. Estrogens inhibit l-glutamate uptake activity of astrocytes via membrane estrogen receptor alpha. Journal of neurochemistry 2003, 86, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegelashvili, G.; Danbolt, N.C.; Schousboe, A. Neuronal soluble factors differentially regulate the expression of the GLT1 and GLAST glutamate transporters in cultured astroglia. Journal of neurochemistry 1997, 69, 2612–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlag, B.D.; Vondrasek, J.R.; Munir, M.; Kalandadze, A.; Zelenaia, O.A.; Rothstein, J.D.; Robinson, M.B. Regulation of the glial Na+-dependent glutamate transporters by cyclic AMP analogs and neurons. Mol Pharmacol 1998, 53, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, R.A.; Liu, J.; Miller, J.W.; Rothstein, J.D.; Farrell, K.; Stein, B.A.; Longuemare, M.C. Neuronal regulation of glutamate transporter subtype expression in astrocytes. J Neurosci 1997, 17, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gozen, O.; Watkins, A.; Lorenzini, I.; Lepore, A.; Gao, Y.; Vidensky, S.; Brennan, J.; Poulsen, D.; Won Park, J.; et al. Presynaptic regulation of astroglial excitatory neurotransmitter transporter GLT1. Neuron 2009, 61, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogaard, R.; Borre, L.; Braunstein, T.H.; Madsen, K.L.; MacAulay, N. Functional modulation of the glutamate transporter variant GLT1b by the PDZ domain protein PICK1. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 20195–20207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, V.; Wiedmer, T.; Ingles-Prieto, A.; Altermatt, P.; Batoulis, H.; Bärenz, F.; Bender, E.; Digles, D.; Dürrenberger, F.; Heitman, L.H.; et al. An Overview of Cell-Based Assay Platforms for the Solute Carrier Family of Transporters. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 722889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadiche, J.I.; Amara, S.G.; Kavanaugh, M.P. Ion fluxes associated with excitatory amino acid transport. Neuron 1995, 15, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolen, B.; Kortzak, D.; Franzen, A.; Fahlke, C. An amino-terminal point mutation increases EAAT2 anion currents without affecting glutamate transport rates. The Journal of biological chemistry 2020, 295, 14936–14947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotti, D.; Danbolt, N.C.; Volterra, A. Glutamate transporters are oxidant-vulnerable: a molecular link between oxidative and excitotoxic neurodegeneration? Trends Pharmacol Sci 1998, 19, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotti, D.; Rolfs, A.; Danbolt, N.C.; Brown, R.H., Jr.; Hediger, M.A. SOD1 mutants linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis selectively inactivate a glial glutamate transporter. Nat Neurosci 1999, 2, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Chen, L.; Sayama, M.; Wu, M.; Hayashi, M.K.; Irie, T.; Ohwada, T.; Sato, K. Leucine 434 is essential for docosahexaenoic acid-induced augmentation of L-glutamate transporter current. The Journal of biological chemistry 2022, 102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairman, W.A.; Sonders, M.S.; Murdoch, G.H.; Amara, S.G. Arachidonic acid elicits a substrate-gated proton current associated with the glutamate transporter EAAT4. Nat Neurosci 1998, 1, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otis, T.S.; Kavanaugh, M.P. Isolation of current components and partial reaction cycles in the glial glutamate transporter EAAT2. J Neurosci 2000, 20, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadiche, J.I.; Kavanaugh, M.P. Macroscopic and microscopic properties of a cloned glutamate transporter/chloride channel. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 7650–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabas, M.H. Cysteine Modification: Probing Channel Structure, Function and Conformational Change. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2015, 869, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabas, M.H.; Stauffer, D.A.; Xu, M.; Karlin, A. Acetylcholine receptor channel structure probed in cysteine-substitution mutants. Science 1992, 258, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, M.; Bendahan, A.; Kanner, B.I. Biotinylation of single cysteine mutants of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 from rat brain reveals its unusual topology. Neuron 1998, 21, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, M.; Menaker, D.; Kanner, B.I. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis reveals a conformationally sensitive reentrant pore-loop in the glutamate transporter GLT-1. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 26074–26080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Tan, F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, L.; Zou, X.; Qu, S. TM4 of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 experiences substrate-induced motion during the transport cycle. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kanner, B.I. Two serine residues of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 are crucial for coupling the fluxes of sodium and the neurotransmitter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999, 96, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocke, L.; Bendahan, A.; Grunewald, M.; Kanner, B.I. Proximity of two oppositely oriented reentrant loops in the glutamate transporter GLT-1 identified by paired cysteine mutagenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 3985–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Arriza, J.L.; Amara, S.G.; Kavanaugh, M.P. Constitutive ion fluxes and substrate binding domains of human glutamate transporters. The Journal of biological chemistry 1995, 270, 17668–17671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrovic, A.D.; Amara, S.G.; Johnston, G.A.; Vandenberg, R.J. Identification of functional domains of the human glutamate transporters EAAT1 and EAAT2. The Journal of biological chemistry 1998, 273, 14698–14706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storck, T.; Schulte, S.; Hofmann, K.; Stoffel, W. Structure, expression, and functional analysis of a Na(+)-dependent glutamate/aspartate transporter from rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1992, 89, 10955–10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yernool, D.; Boudker, O.; Jin, Y.; Gouaux, E. Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature 2004, 431, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Kusakizako, T.; Jin, C.; Zhou, X.; Ohgaki, R.; Quan, L.; Xu, M.; Okuda, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Yamashita, K.; et al. Structural insights into inhibitory mechanism of human excitatory amino acid transporter EAAT2. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Geng, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y. Structural basis of ligand binding modes of human EAAT2. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardetzky, O. Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature 1966, 211, 969–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudker, O.; Ryan, R.M.; Yernool, D.; Shimamoto, K.; Gouaux, E. Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature 2007, 445, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdon, G.; Boudker, O. Crystal structure of an asymmetric trimer of a bacterial glutamate transporter homolog. Nature structural & molecular biology 2012, 19, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, N.; Georgieva, E.R.; Zhou, Z.; Stolzenberg, S.; Cuendet, M.A.; Khelashvili, G.; Altman, R.B.; Terry, D.S.; Freed, J.H.; Weinstein, H.; et al. Transport domain unlocking sets the uptake rate of an aspartate transporter. Nature 2015, 518, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, N.; Ginter, C.; Boudker, O. Transport mechanism of a bacterial homologue of glutamate transporters. Nature 2009, 462, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canul-Tec, J.C.; Assal, R.; Cirri, E.; Legrand, P.; Brier, S.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Reyes, N. Structure and allosteric inhibition of excitatory amino acid transporter 1. Nature 2017, 544, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, W.; Beard, H.S.; Farid, R. Use of an induced fit receptor structure in virtual screening. Chemical biology & drug design 2006, 67, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.; Day, T.; Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Farid, R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2006, 49, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, B.; Schneider, N.; Erichsen, M.N.; Huynh, T.H.; Fahlke, C.; Bunch, L.; Jensen, A.A. Allosteric modulation of an excitatory amino acid transporter: the subtype-selective inhibitor UCPH-101 exerts sustained inhibition of EAAT1 through an intramonomeric site in the trimerization domain. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 1068–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.; Pant, S.; Wu, Q.; Cater, R.J.; Sobti, M.; Vandenberg, R.J.; Stewart, A.G.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Font, J.; Ryan, R.M. Glutamate transporters have a chloride channel with two hydrophobic gates. Nature 2021, 591, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, D.; Miller, B.; Sarantis, M. Arachidonic acid as a messenger in the central nervous system. Seminars in Neuroscience 1993, 5, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piomelli, D. Arachidonic acid in cell signaling. Current opinion in cell biology 1993, 5, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piomelli, D.; Greengard, P. Lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid in neuronal transmembrane signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1990, 11, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aid, S.; Vancassel, S.; Poumes-Ballihaut, C.; Chalon, S.; Guesnet, P.; Lavialle, M. Effect of a diet-induced n-3 PUFA depletion on cholinergic parameters in the rat hippocampus. Journal of lipid research 2003, 44, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, E.M.; Dyer, R.A.; Innis, S.M. High dietary omega-6 fatty acids contribute to reduced docosahexaenoic acid in the developing brain and inhibit secondary neurite growth. Brain Res 2008, 1237, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, S.I. Translational studies on regulation of brain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) metabolism in vivo. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 2013, 88, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, N., Jr.; Litman, B.; Kim, H.Y.; Gawrisch, K. Mechanisms of action of docosahexaenoic acid in the nervous system. Lipids 2001, 36, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A. Cerebral endothelium and astrocytes cooperate in supplying docosahexaenoic acid to neurons. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 1993, 331, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.A. Polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis and release by brain-derived cells in vitro. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN 2001, 16, 195-200; discussion 215-121. [CrossRef]

- Williard, D.E.; Harmon, S.D.; Kaduce, T.L.; Preuss, M.; Moore, S.A.; Robbins, M.E.; Spector, A.A. Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis from n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in differentiated rat brain astrocytes. Journal of lipid research 2001, 42, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazan, N.G. Synaptic lipid signaling: significance of polyunsaturated fatty acids and platelet-activating factor. Journal of lipid research 2003, 44, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.T.; Orr, S.K.; Bazinet, R.P. The emerging role of group VI calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in releasing docosahexaenoic acid from brain phospholipids. Journal of lipid research 2008, 49, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokin, M.; Sergeeva, M.; Reiser, G. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid release in rat brain astrocytes is mediated by two separate isoforms of phospholipase A2 and is differently regulated by cyclic AMP and Ca2+. British journal of pharmacology 2003, 139, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strokin, M.; Sergeeva, M.; Reiser, G. Prostaglandin synthesis in rat brain astrocytes is under the control of the n-3 docosahexaenoic acid, released by group VIB calcium-independent phospholipase A2. Journal of neurochemistry 2007, 102, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuratko, C.N.; Barrett, E.C.; Nelson, E.B.; Salem, N., Jr. The relationship of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) with learning and behavior in healthy children: a review. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2777–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtcheva, S.; Venance, L. Control of Long-Term Plasticity by Glutamate Transporters. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzingounis, A.V.; Wadiche, J.I. Glutamate transporters: confining runaway excitation by shaping synaptic transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007, 8, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, F.; Weinberg, R.J. Shaping excitation at glutamatergic synapses. Trends in neurosciences 1999, 22, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.R.; Felix, L.; Zeug, A.; Dietrich, D.; Reiner, A.; Henneberger, C. Astroglial Glutamate Signaling and Uptake in the Hippocampus. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2017, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi-Jones, D. Impaired corticostriatal LTP and depotentiation following iPLA2 inhibition is restored following acute application of DHA. Brain research bulletin 2015, 111, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, S.; Ikegaya, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Nishiyama, N.; Matsuki, N. Docosahexaenoic acid improves long-term potentiation attenuated by phospholipase A(2) inhibitor in rat hippocampal slices. British journal of pharmacology 2001, 132, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).