Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

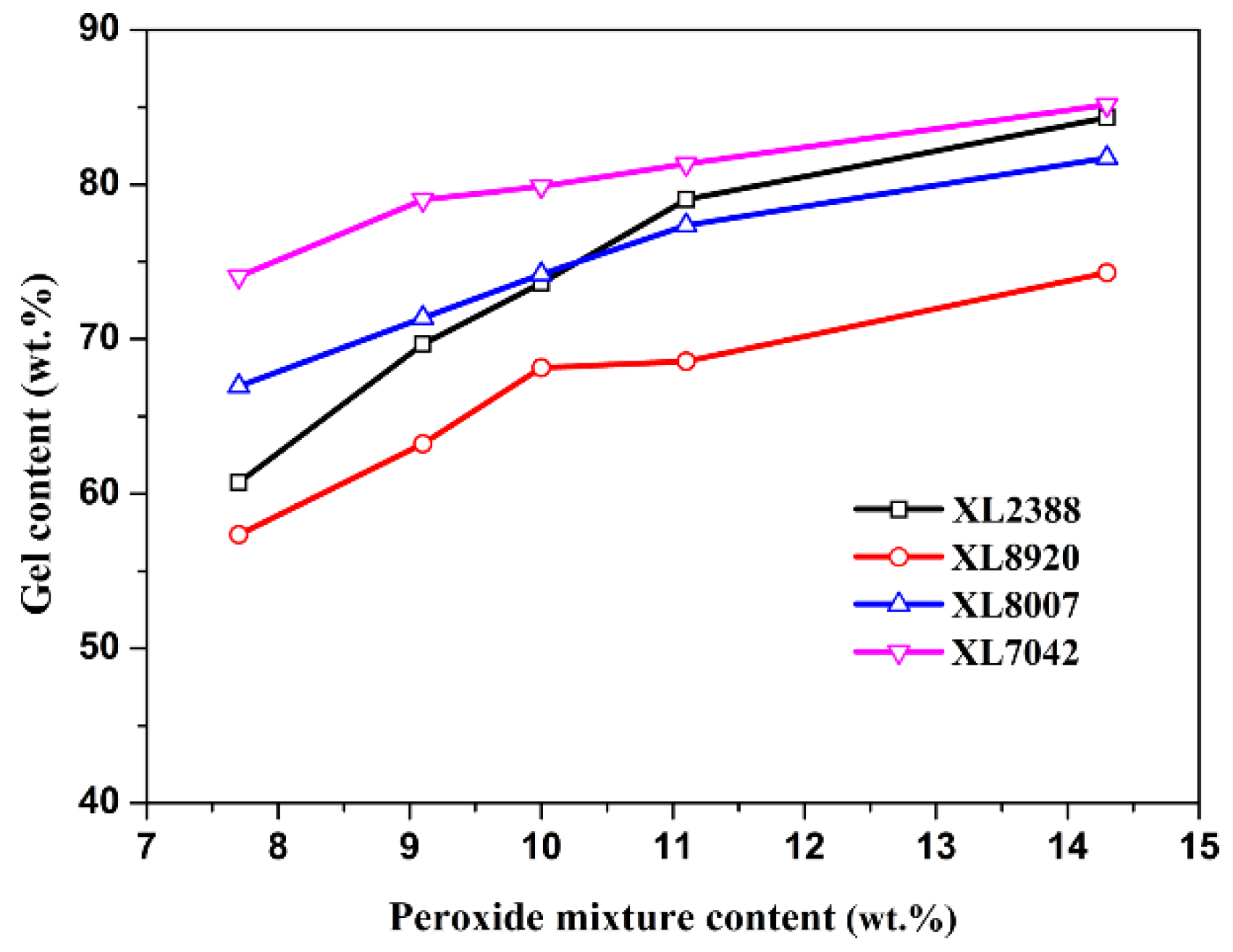

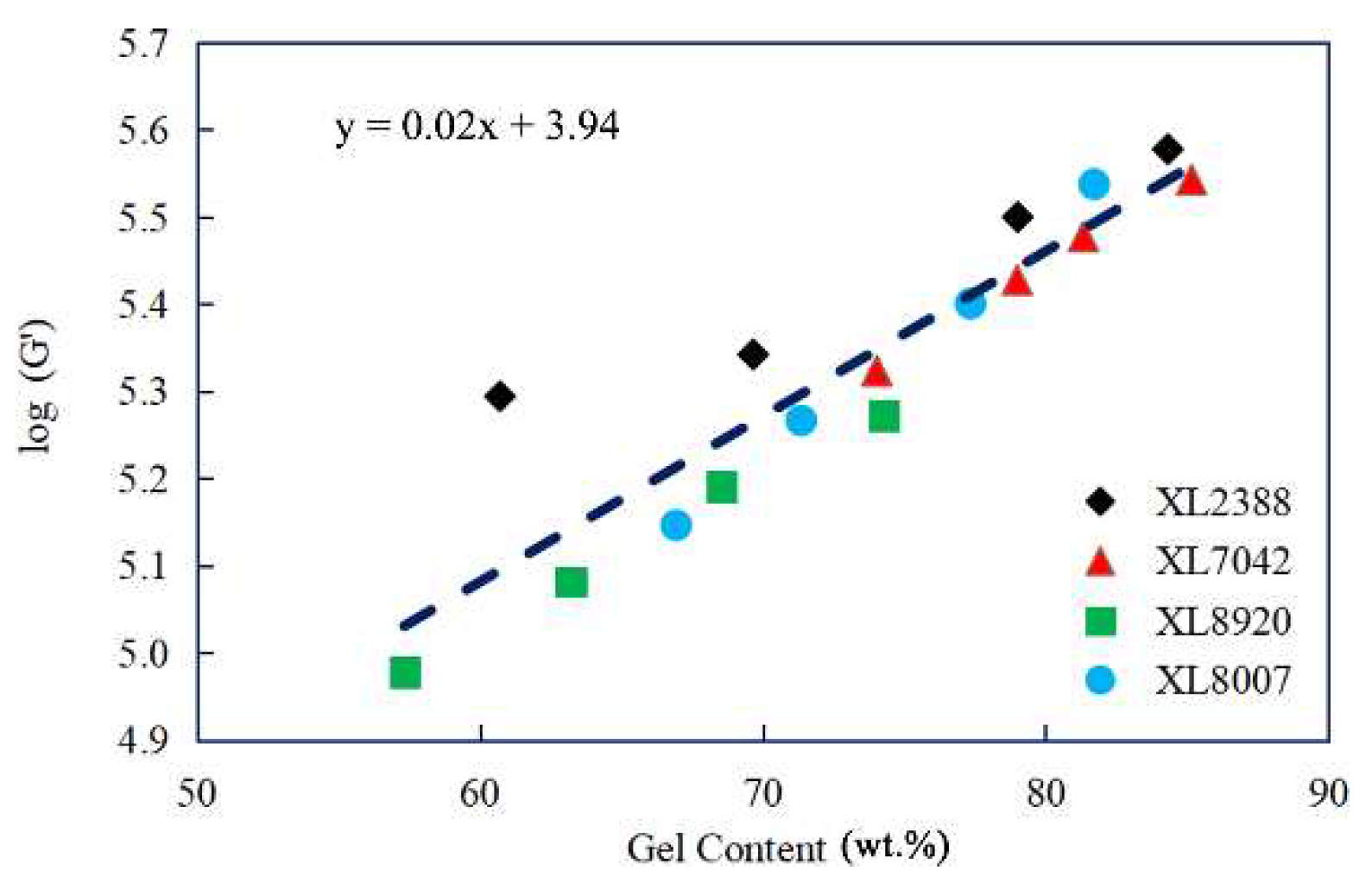

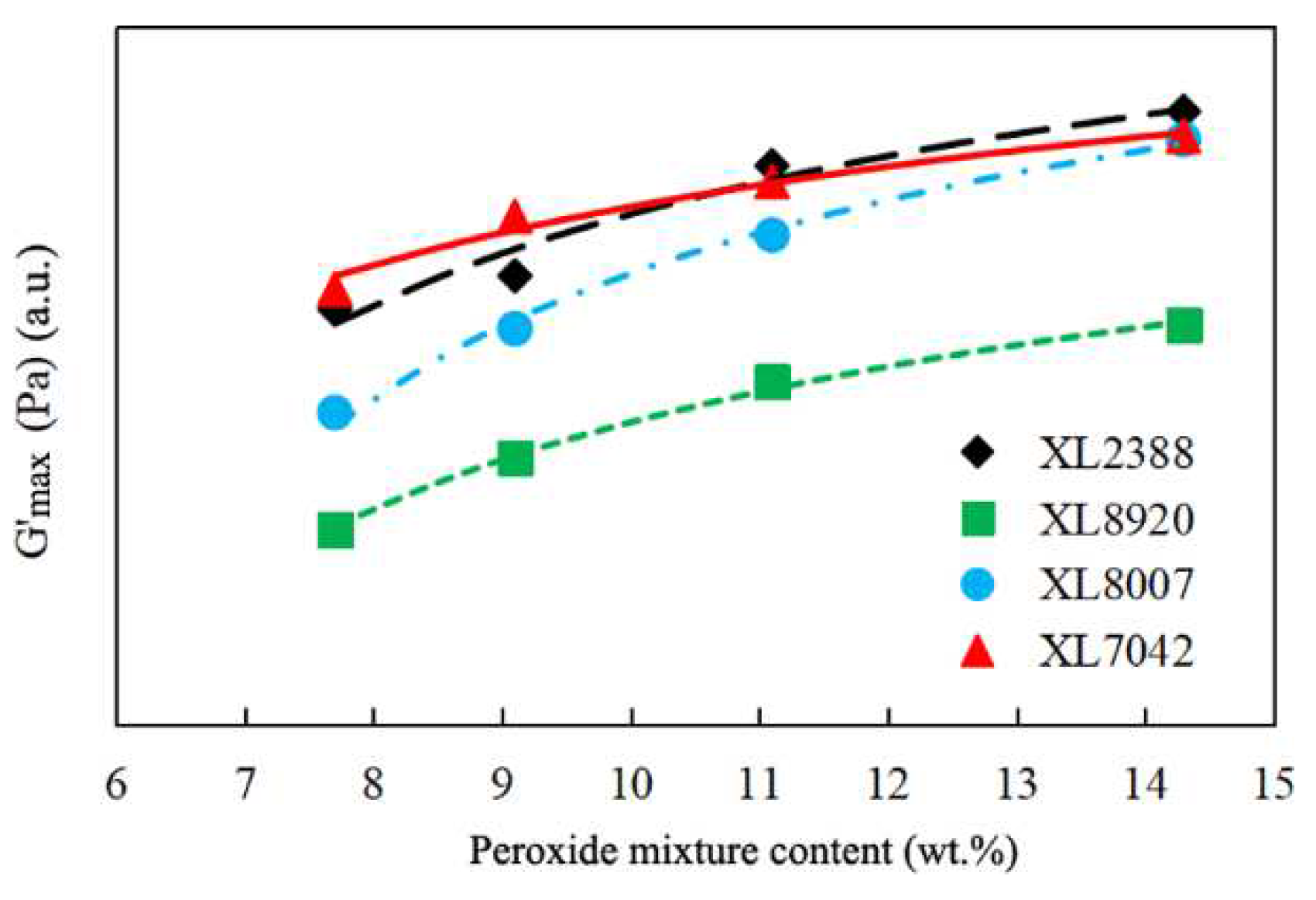

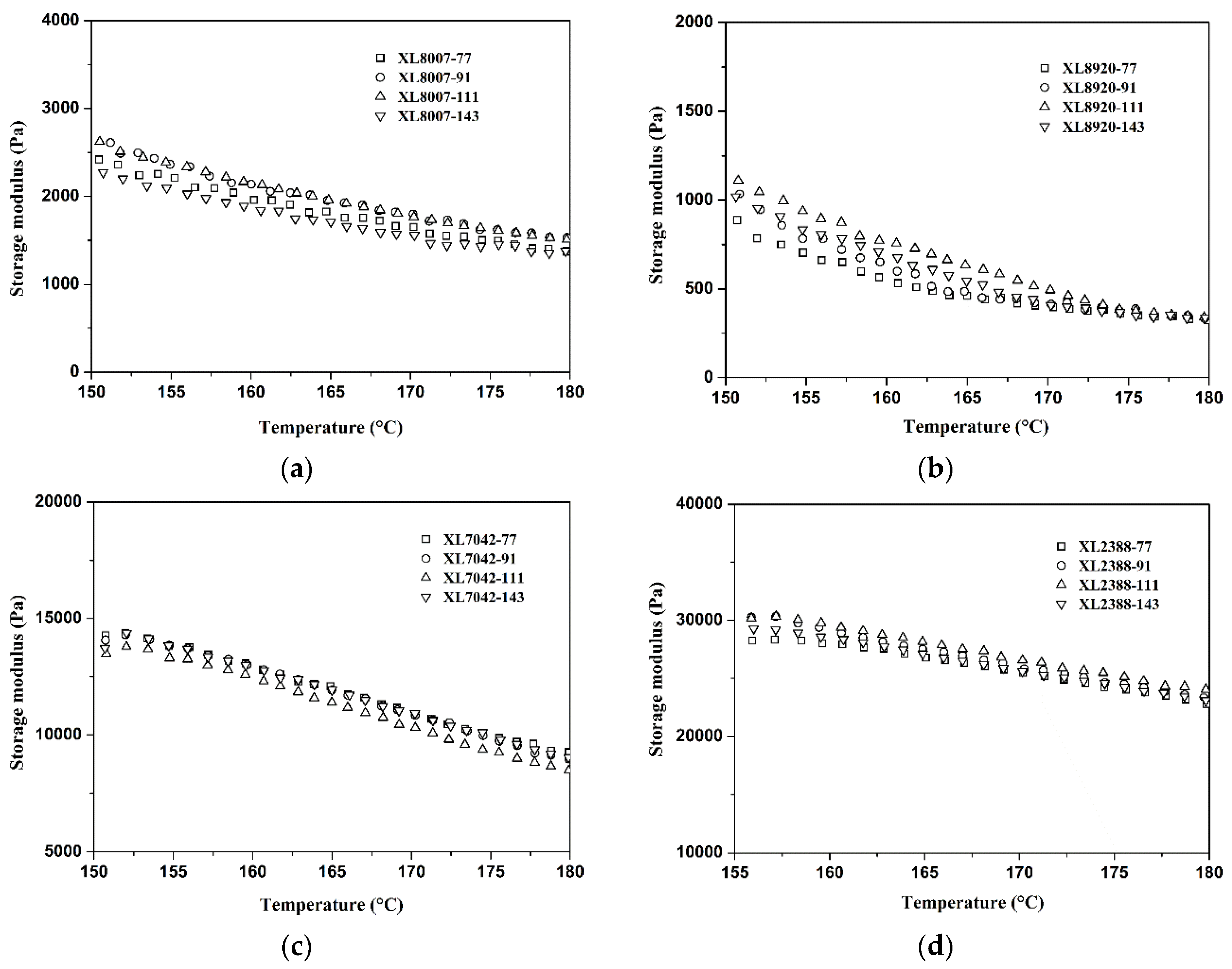

2.1. Gel Content and Storage Modulus Analysis of XLPE

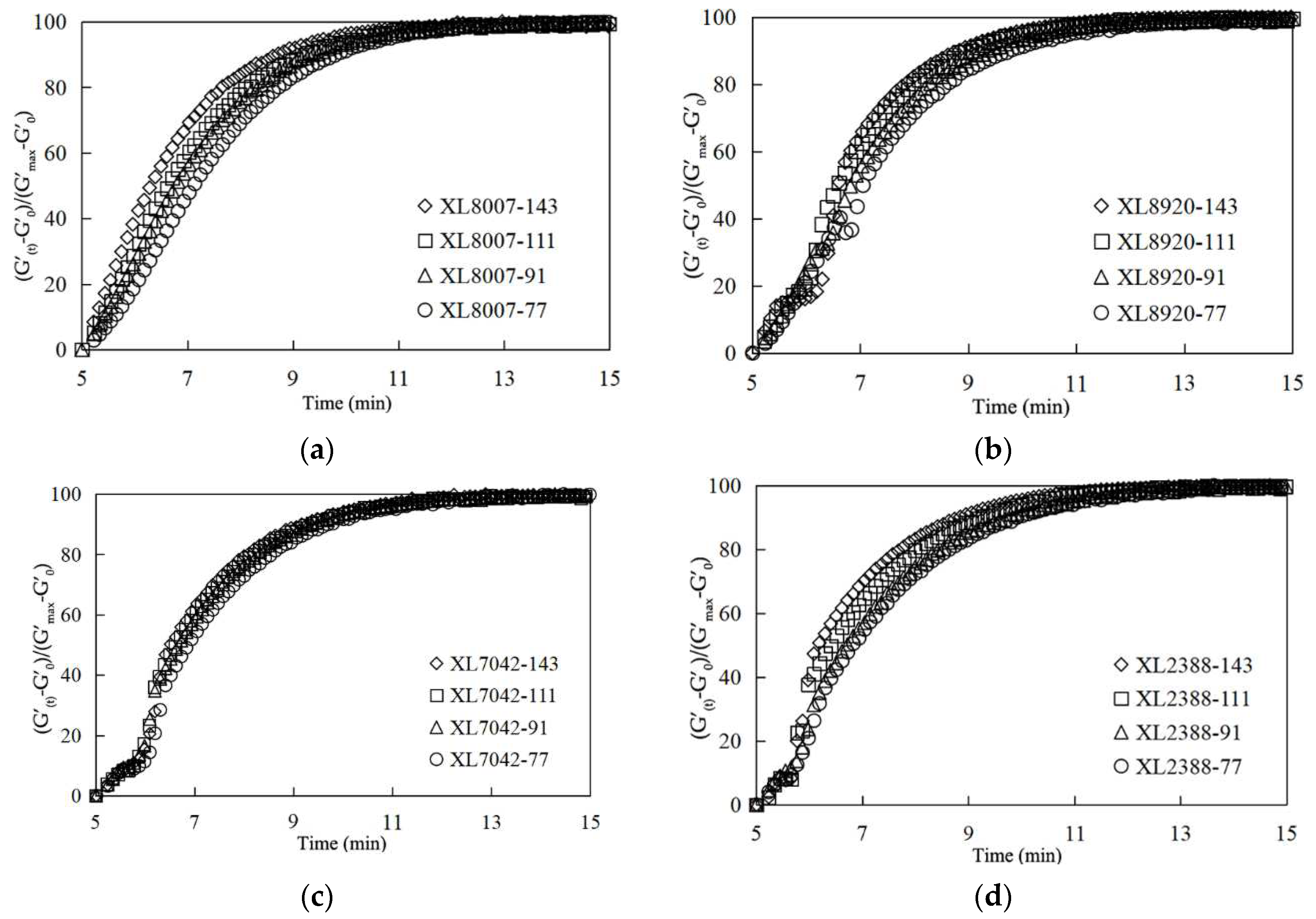

2.2. Crosslinking Rate of XLPE

2.3. Crosslinking Behavior Simulation of XLPE

2.4. Melt Processibility of XLPE by rheological measurement

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eagan, J.M.; Xu, J.; Di Girolamo, R.; Thurber, C.M.; Macosko, C.W.; LaPointe, A.M.; Bates, F.S.; Coates, G.W. Combining polyethylene and polypropylene: Enhanced performance with PE/iPP multiblock polymers. Science 2017, 355, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürzel, M.; Mihan, S.; Mülhaupt, R. From multisite polymerization catalysis to sustainable materials and all-polyolefin composites. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1398–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, A.; Roland, S.; Colin, X. Physico-chemical characterization of the blooming of Irganox 1076® antioxidant onto the surface of a silane-crosslinked polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2020, 171, 109046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkari, N.M.; Doğan, Ö.; Bat, E.; Mohseni, M.; Ebrahimi, M. Assessing effects of (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane self-assembled layers on surface characteristics of organosilane-grafted moisture-crosslinked polyethylene substrate: A comparative study between chemical vapor deposition and plasma-facilitated in situ grafting methods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 497, 143751. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, S.; Komvopoulos, K. Physicochemical properties and morphology of fluorocarbon films synthesized on crosslinked polyethylene by capacitively coupled octafluorocyclobutane plasma. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 4358–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisinha, K.; Chuaythong, P. Reprocessable silane-crosslinked polyethylene: property and utilization as toughness enhancer for high-density polyethylene. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 5182–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q. Selective decomposition process and mechanism of Si−O−Si cross-linking bonds in silane cross-linked polyethylene by solid-state shear milling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 12896–12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisinha, K.; Boonkongkaew, M. Improved silane grafting of high-density polyethylene in the melt by using a binary initiator and the properties of silane-crosslinked products. J. Polym. Res. 2013, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Y.Q.; Ehsan, H.; Mehmood, U.; Irfan, M.S.; Saeed, F. A novel two-step melt blending method to prepare nano-silanized-silica reinforced crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) nanocomposites. Poly. Bull. 2022, 79, 10077–10093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camalov, M.; Orucov, A.; Hashimov, A.; Arikan, O.; Akin, F. Breakdown strength analysis of XLPE insulation types: A comparative study for multi-layer structure and voltage rise rate. Electr. Pow. Syst. Res. 2023, 223, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.A.; Hong, R.; Yang, X.; Huang, S.S.; Gul, R.M.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, J.Z.; Li, K.; Li, Z.M. Synergy stabilization of vitamin E and D-sorbitol on crosslinked ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene for artificial joint under in-vitro clinically relevant accelerated aging. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2023, 214, 110382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jeong, J.H.; Hong, G.; Cho, H.K.; Baek, B.K.; Koo, C.M.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.W. Effect of Solvents on De-Cross-Linking of Cross-Linked Polyethylene under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 6633–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Yu, K.; Li, K.; Hou, J.; Yang, Y.; Shen, C.; Chen, J.; Park, C.B. Preparation and microcellular foaming of crosslinked polyethylene-octene elastomer by ionic modification. J. Supercrit. Fluid. 2023, 202, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, D.; Hamedi, H.; Damirchi, B.; Yilmaz, D.E.; Penrod, K.; Hunter Woodward, W.H.; Moore, J.; Lanagan, M.T.; van Duin, A.C.T. Atomistic-scale insights into the crosslinking of polyethylene induced by peroxides. Polymer 2019, 183, 121901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, E.C.; Failla, M.D.; Tuckart, W.R. The effect of crosslinks on the sliding wear of high-density polyethylene. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 64, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.J.; Throne, J.L. Rotational Molding Technology; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenegger-Uray, A.; Rieß, G.; Lucyshyn, T.; Holzer, C.; Kern, W. Physical foaming and crosslinking of polyethylene with modified talcum. Polymers 2019, 11, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigehiko, A.; Masayuki, Y. Study on the foaming of crosslinked polyethylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 79, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Marcilla, A.; García-Quesada, J.C.; Ruiz-Femenia, R.; Beltrán, M.I. Crosslinking of rotational molding foams of polyethylene. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2007, 47, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Leonov, A.I. A kinetic model for sulfur accelerated vulcanization of a natural rubber compound. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1996, 61, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.M.; Wang, Z.Z.; Liang, X.M.; Hu, Y. Non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of silane crosslinked polyethylene. Polymer Testing 2005, 24, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, I.; Luyt, A.S. Thermal and mechanical properties of LLDPE crosslinked with gamma radiation. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2001, 71, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasciani, C.; Alejo, C.J.B.; Grenier, M.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C.; Scaiano, J.C. High temperature organic reactions at room temperature using plasmon excitation: decomposition of dicumyl peroxide. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, C.; Wang, Z.; Gui, Z.; Hu, Y. Silane grafting and crosslinking of ethylene-octene copolymer. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsich, H.S.Y. Kinetic model of cure reaction and filler effect. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1982, 27, 3265–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.H.U.; Gustafsson, B.; Hjertberg, T. Crosslinking of bimodal polyethylene. Polymer 2004, 45, 2577–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.H.; Liang, W.B.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, X.L.; Lai, S.Y.; Li, G.X.; Wang, D.J. Crosslinking kinetics of polyethylene with small amount of peroxide and its influence on the subsequent crystallization behaviors. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 34, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, J.G.; Zhu, S.P.; Kang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, M. Effects of polymerization and crosslinking technologies on the crystallization behaviors and gel network of crosslinked polyethylene. J. Macromol. Sci. B. 2012, 51, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshrah, M.; Adeyemi, I.; Janajreh, I. Kinetic study on thermal degradation of crosslinked polyethylene cable waste. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Liu, D.; Wu, L.F.; Wang, Z. Multiple kinetic processes of lamellar growth in crystallization of stretched lightly crosslinked polyethylene. Polymer 2023, 265, 125586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Z.; Kang, D.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Xin, Z. Novel determining technique for the entanglement degree of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. Mater. Lett. 2023, 349, 134783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | XL2388 | XL8920 | XL8007 | XL7042 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40.53 | 35.33 | 38.24 | 39.22 | |

| 6.38 | 5.9 | 5.46 | 4.51 | |

| C | 48.11 | 42.58 | 46.9 | 50.38 |

| Ideal maximum degree of crosslinking | 89 | 78 | 85 | 90 |

| Adj. q-square | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.999 |

| Parameter | Peroxide Mixture Content (wt.%) | XL7042 | XL8007 | XL8920 | XL2388 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ti | 7.7 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.31 | -0.22 |

| 9.1 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.30 | -0.12 | |

| 11.1 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.10 | |

| 14.3 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.16 | |

| A0 | 7.7 | 238972 | 158665 | 107356 | 217904 |

| 9.1 | 279737 | 199809 | 133582 | 235183 | |

| 11.1 | 309557 | 263437 | 160588 | 322242 | |

| 14.3 | 346514 | 342194 | 194874 | 380893 | |

| k2 | 7.7 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| 9.1 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.42 | |

| 11.1 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.57 | |

| 14.3 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.68 | |

| k6 | 7.7 | 0.0086 | 0.0111 | 0.0108 | 0.0089 |

| 9.1 | 0.0051 | 0.0075 | 0.0104 | 0.0059 | |

| 11.1 | 0.0027 | 0.0037 | 0.0024 | 0.0019 | |

| 14.3 | 0.0015 | 0.0008 | 0.0031 | 0.0011 | |

| phi | 7.7 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 |

| 9.1 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | |

| 11.1 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | |

| 14.3 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 | 6.1403E-05 |

| PE Resin Type | PE Resin Code | PE Resin Content (wt.%) | Peroxide Mixture Content (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE 8007 | XL8007-77 | 92.3 | 7.7 |

| XL8007-91 | 90.9 | 9.1 | |

| XL8007-111 | 88.9 | 11.1 | |

| XL8007-143 | 85.7 | 14.3 | |

| LLDPE 7042 | XL7042-77 | 92.3 | 7.7 |

| XL7042-91 | 90.9 | 9.1 | |

| XL7042-111 | 88.9 | 11.1 | |

| XL7042-143 | 85.7 | 14.3 | |

| HDPE 8920 | XL8920-77 | 92.3 | 7.7 |

| XL8920-91 | 90.9 | 9.1 | |

| XL8920-111 | 88.9 | 11.1 | |

| XL8920-143 | 85.7 | 14.3 | |

| MDPE 2388 | XL2388-77 | 92.3 | 7.7 |

| XL2388-91 | 90.9 | 9.1 | |

| XL2388-111 | 88.9 | 11.1 | |

| XL2388-143 | 85.7 | 14.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).