1. Introduction

Olive oil, recognized for its nutritional [

1], sensory [

2], and medicinal attributes [

3], holds a unique place in the culinary [

4] and Mediterranean landscapes [

5]. For centuries, olive cultivation has been intertwined with human history, playing a pivotal role in various cultures and civilizations [

6]. Traditional olive production accounts for a large proportion of the olive orchards, particularly in marginal areas. In general, the traditional system can be described as a low-intensity farming system [

7]. It is associated with old trees grown at low density without irrigation, giving low yields, receiving low agrochemical inputs, and with a low degree of mechanization [

8]. Olive harvesting in traditional olive orchards is mainly performed by manual methods using long poles or sticks [

9], and temporal delays between harvest and milling are common [

10].

The Middle East region plays a special role in olive cultivation. It seems that domestication and cultivation of olives started in this region ca. 6500 years ago, earlier than any other place in the world [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Hence, this area has the longest tradition of olive cultivation.

The traditional rainfed olive orchards in the Middle East grow ‘Souri’ as the predominant cultivar [

15,

16]. Those orchards are not adapted for mechanical harvesting, and manual harvesting leads to increased labor costs. In addition, the productivity of those orchards is relatively low compared to intensive orchards, and their low profitability is raising concern about their future. One of the solutions proposed in Europe for the low profitability of the traditional orchards was to brand those oils under the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) system, which allows the growers to get higher prices for their virgin olive oil (VOO) [

17]. However, for the branding of VOO, the first step must be to obtain extra virgin olive oil (EVOO). Past surveys have shown that most of the oil produced in traditional orchards does not meet this quality standard. We therefore assessed the causes of VOO deterioration in traditional orchards in the Middle East. Specifically, we explored the potential of the traditionally grown olives to produce high-quality oil and assessed the overall effect of the growers’ practices, harvesting methods and fruit storage from harvest to mill on the oil’s quality.

2. Materials and Methods

Three aspects were studied: the effect of general orchard management, the effect of harvesting method and the effect of fruit storage practice.

2.1. Orchard Locations

Eleven traditional, rainfed olive orchards of different ages were selected from the south (32o22’18.35’’N35o02’17.29’’E) to the north (33o04’36.78’’N35o30’49.97’’E) of Israel, in the summer of 2021. In each orchard, six bearing trees (replicates) with medium to high fruit load were selected.

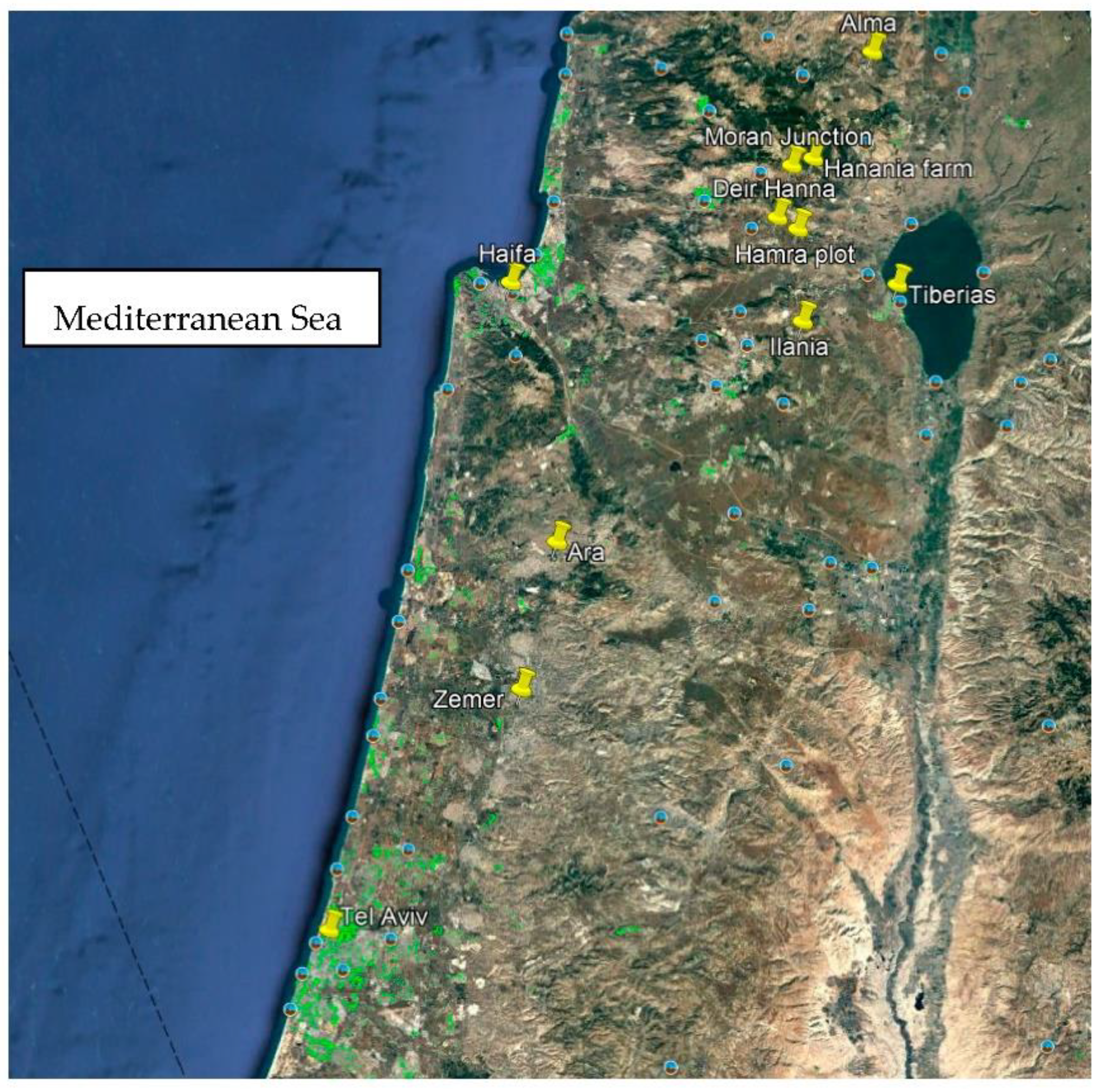

The geographical distribution of the different orchard locations is presented in

Figure 1. The southernmost orchard was selected in the southernmost region where rainfed olives can still be cultivated commercially in terms of precipitation. From that region, the selected orchards followed a southwest-to-northeast line.

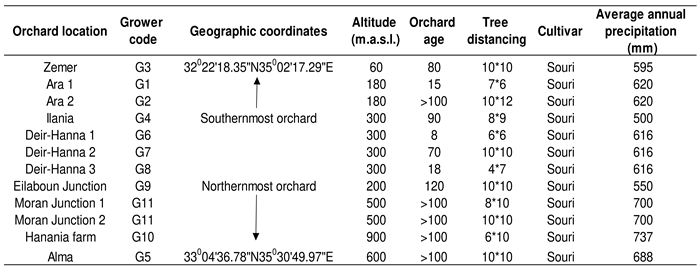

Orchard characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The southernmost orchards were at a low altitude of 60–180 m.a.s.l. and the altitude increased with the northward progression of the orchard locations.

2.2. Fruit sampling

2.2.1. Effect of commercial practices on oil quality

In all 11 selected traditional rainfed olive orchards, the soil is stony and calcareous, with a medium to heavy texture. The climate is typical Mediterranean with a cool, rainy winter and a dry, hot summer. A few days before the commercial harvest, a 2-kg sample of olives was hand-picked from each selected tree in each orchard.

2.2.2. Effect of harvest method

In 4 of the 11 selected orchards, simultaneous with the grower’s harvest, three harvest methods were tested in four trees (replicates): 1) manual picking, 2) the traditional harvest method, i.e., beating the crown with a pole to detach the fruit and collecting them on nets extended on the ground, and 3) using electric combs (Pellenc, France) to detach the fruit and collect them on nets extended on the ground. In each orchard, a 2-kg subsample of olives was taken from each tree and harvest method. The trees were randomly allocated for the different harvesting methods.

2.2.3. Effect of fruit storage

In two of four selected orchards, two types of storage were tested during the commercial harvest: in ventilated 20-kg boxes and in non-ventilated 20-kg plastic bags. Three storage times were tested: 24, 48, and 120 h. Each combination of storage method and storage duration had four replicates.

2.3. Fruit characterization

The following fruit parameters were measured on a subsample of 100 fruit: rotten (moldy) fruit index and injury index. Both indexes were on a scale of 0–10, where 0 was no rotting or injury and 10 was heavily rotten or injured. Rotting and injury intensities were estimated for each of the 100 fruit in the subsample, and the number of fruit from a given category was multiplied by the intensity level, resulting in a rotting/injury intensity. The minimum possible value of this parameter was zero and the maximum was 10.

2.4. Laboratory and commercial oil extraction and oil content determination

Commercial oil extraction performed in 3-phase medium-sized olive mills. Laboratory oil extraction of all olive samples conducted using a laboratory-scale olive mill (Abencor, MC2 Ingenieria y Sistemas, Seville, Spain). After extraction, the oil filtered using filtering paper. A subsample from the olive paste was taken to determine oil and water content using a NIR spectrometer (OliveScan, Foss, Denmark) [

18].

2.5. Oil chemical analysis

An olive oil sample was taken from the olive mill at each orchard, representing commercial harvesting and oil-extraction processes. This sample was filtered and analyzed with the olive oil samples obtained from the laboratory extraction. Chemical analysis was performed as described previously [

19].

Free fatty acid (FFA) levels were determined using International Organization for Standardization (ISO) analytical method 660. FFA level was expressed as percent oleic acid. Phenolic compounds were isolated from a solution of oil in hexane by double-extraction with methanol–water (60:40, v/v). Polyphenol content, expressed as tyrosol equivalents (mg kg

-1 oil), was determined with a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) at a wavelength of 735 nm, using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent [

20]. Fatty acid composition was determined by gas chromatography following cold methylation according to International Olive Council (IOC) method COI/T.20/Doc. No. 24, 2001. Chromatographic analysis was performed using an Agilent 6850 N gas chromatograph equipped with a mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and DB23 capillary column (60 m long, 0.25 mm diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). Helium was employed as the carrier gas (Maxima, Ashdod, Israel). The detector temperature was set to 250

oC. The oven temperature was held at 175

oC for 5 min, then increased at 5

oC min

-1 to 240

oC and held for 7 min until the end of the 25-min run. The injection volume was 1 µL (regulation EEC 2568/91, corresponding to American Oil Chemists’ Society [AOCS] method Ch2-91). Fatty acids were identified by comparing retention time with standard compounds (FAME Mix C8–C24, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The relative composition of fatty acids in the olive oil was determined as the percentage of total fatty acids.

Total carotenoid content was measured according to the method described by Salvador

et al. [

21] modified for a 96-well plate: 420 µL oil was mixed with 980 µL isooctane to obtain 30% oil in isooctane, and 200 µL was pipetted into a 96-well plate and read at 470 nm, in four replicates. Path-length correction and specific extinction values were used. Sterol analysis was modified for a 96-well plate from Araújo

et al. [

22]. A 100-µL aliquot of oil was mixed with 900 µL chloroform, and 300 µL was pipetted out and mixed with 200 µL chloroform; 200 µL of this solution was pipetted into a 96-well plate , which was kept in the dark for 15 min then read at 625 nm. Tocopherol analysis was modified for a 96-well plate from Wong

et al. [

23]. A 40-µL aliquot of oil was weighed, and 1 mL toluene was added and mixed well; 700 µL 2,2’-bipyridine (0.07% w/v in 95% aqueous ethanol) and 100 µL FeCl

3·6H

2O (0.2% w/v in 95% aqueous ethanol) were added in that order. The solution was made up to 2 mL with 95% aqueous ethanol. After standing for 1 min, absorbance at 520 nm was determined using a blank solution as a reference, prepared as above, but omitting the oil. Solutions were protected from strong light during color development. The method was calibrated by preparing standards containing 0–240 µg of pure 𝛼-tocopherol in 10 mL of toluene and then analyzing as above.

2.6. Oil sensory analysis

Sensory assessment was performed by an IOC-recognized panel (Israel’s Southern Panel) following the IOC COI/T.20/Doc. No 15/Rev method regulation.

2.7. Data analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using JMP software version 16 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significant differences were determined by Student’s t-test at P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of current commercial processes on oil quality

In this experiment, we assessed the effect of the current commercial processes used by the farmers in the oil-production chain (which includes harvest, fruit storage until milling [time and storage conditions and milling] and oil extraction) and compared them to experimental laboratory-scale processes. The experimental process aimed to minimize oil deterioration and thus reflects the quality potential of the oil if the harvesting and milling are done properly.

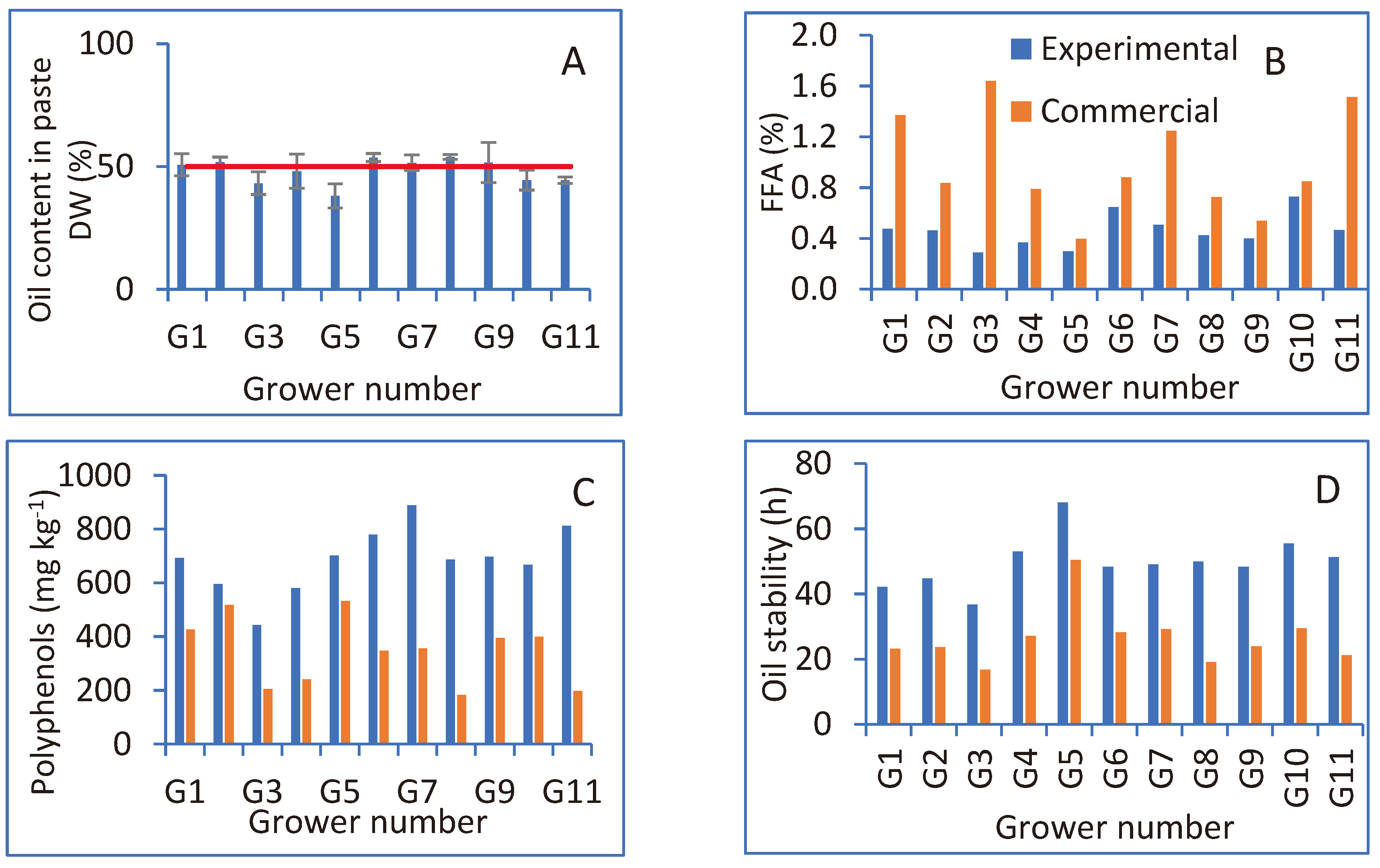

Oil content in the paste, based on the dry weight of the sampled fruit, is presented in

Figure 2A. In most orchards, oil reached the maximum possible content of 50% [

18], or was very close to this value at the time of the experimental harvest.

FFA content in the oil obtained from each of the sampled orchards is presented in

Figure 2B. For all orchards, FFA values of the experimental sampling were lower than those measured in the oil obtained from the commercial harvest and oil extraction. While in the experimental harvest, all of the samples were below 0.8%, the threshold for EVOO, in the commercial harvest, most of the samples (6 out of 11) were above this threshold and did not meet the standard for EVOO.

Polyphenol content in the oil obtained from each sampled orchard is presented in

Figure 2C. In all 11 orchards, oil polyphenol content in the experimental harvested fruit was higher than in the oil from the commercial harvest.

Oil stability in the different oil samples is presented in

Figure 2D. Oil stability values in the experimental harvested fruit were significantly higher than those measured in the oil from the commercial harvest.

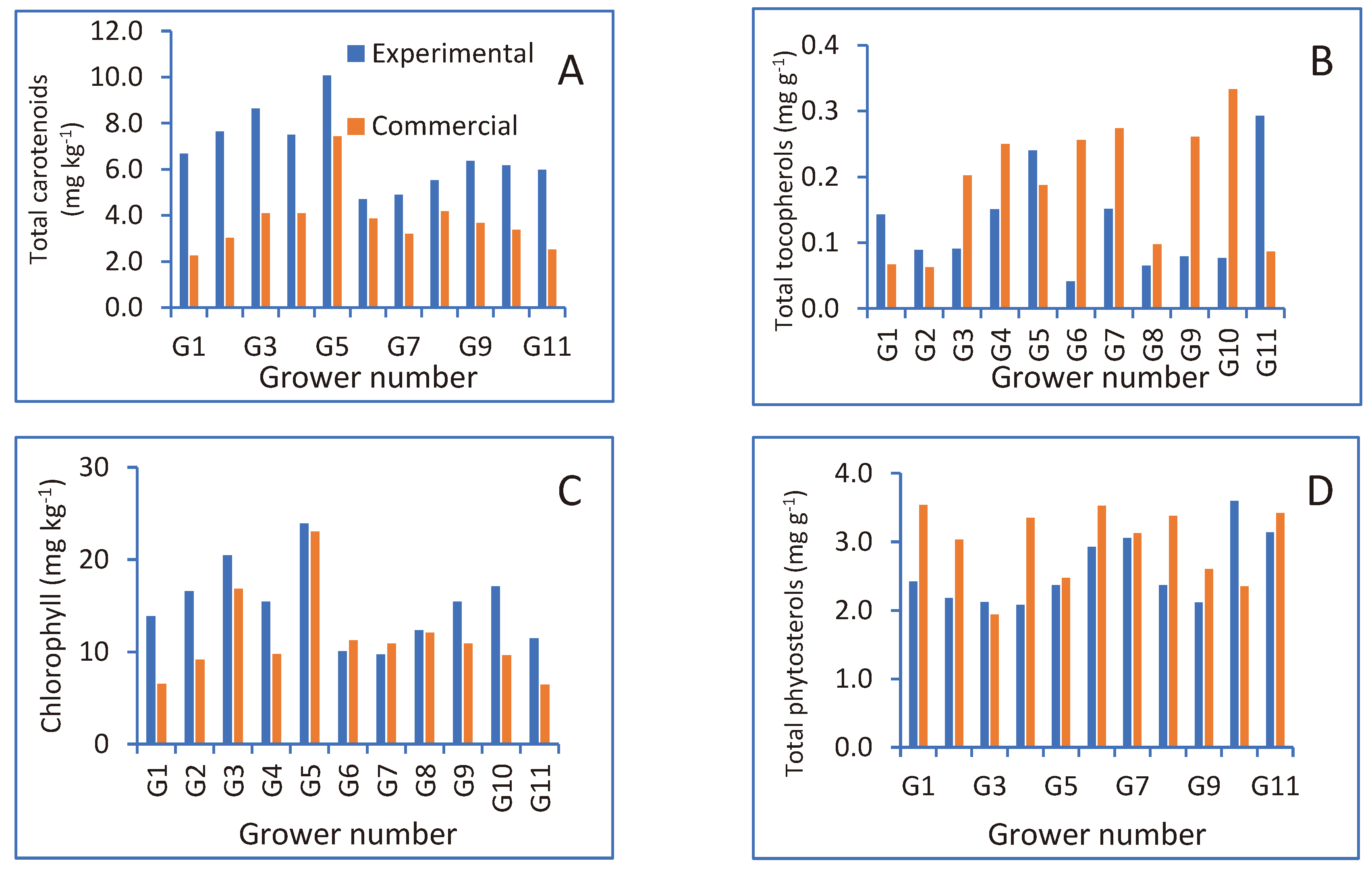

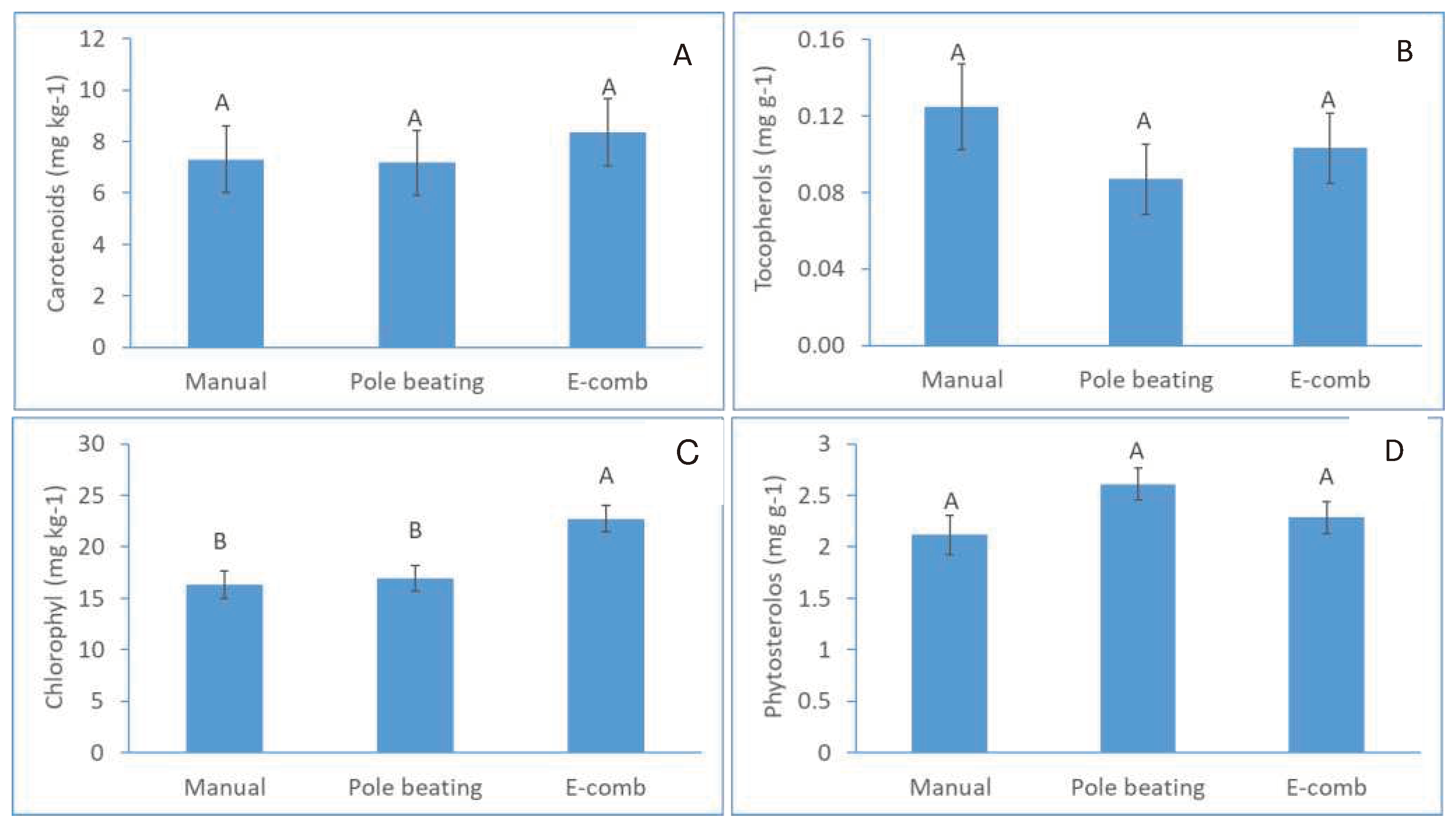

The oil’s secondary metabolite content is presented in

Figure 3A–D. Oil carotenoid content (

Figure 3A) and oil chlorophyll content (

Figure 3C) were higher in the experimental harvested olives compared to the commercial harvest and oil extraction. Oil tocopherol content (

Figure 3B) showed no consistent trend between experimental and commercially harvested olives. Although phytosterol content was higher in the experimentally harvested olives compared to the commercial harvest in most cases (

Figure 3D), the differences were not statistically significant.

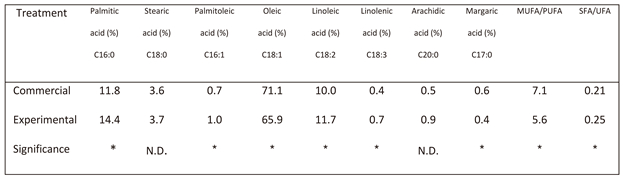

There was a significant difference in fatty acid profile between the oil obtained from the commercial process and that obtained by the experimental one (

Table 2). The farmer’s practice led to a significant elevation in oleic acid, margaric acid and the MUFA/PUFA ratio, and a significant reduction in palmitoleic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid and the SFA/UFA ratio.

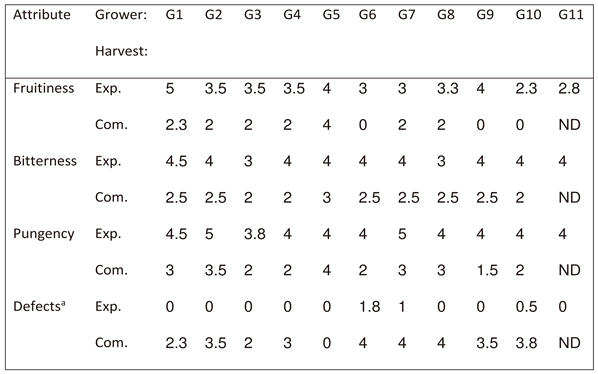

The average fruitiness level in the experimentally harvested fruit was 3.5, whereas in the commercial harvest, it was only 1.6. Average olive oil bitterness was 3.8 in the experimental harvest and 2.4 in the commercial one, and oil pungency, which was 4.2 in the experimental harvest, was only 2.6 in the commercial harvest. In the experimental harvest, 3 out of the 10 oils contained defects and defect level was relatively low (<2), whereas in the commercial harvest, 9 out of the 10 oils contained defects, and their levels were high, ranging between 2 and 4. Hence, the experimental harvest resulted in better positive attributes and less negative attributes than the commercial one.

3.2. Effect of harvest method

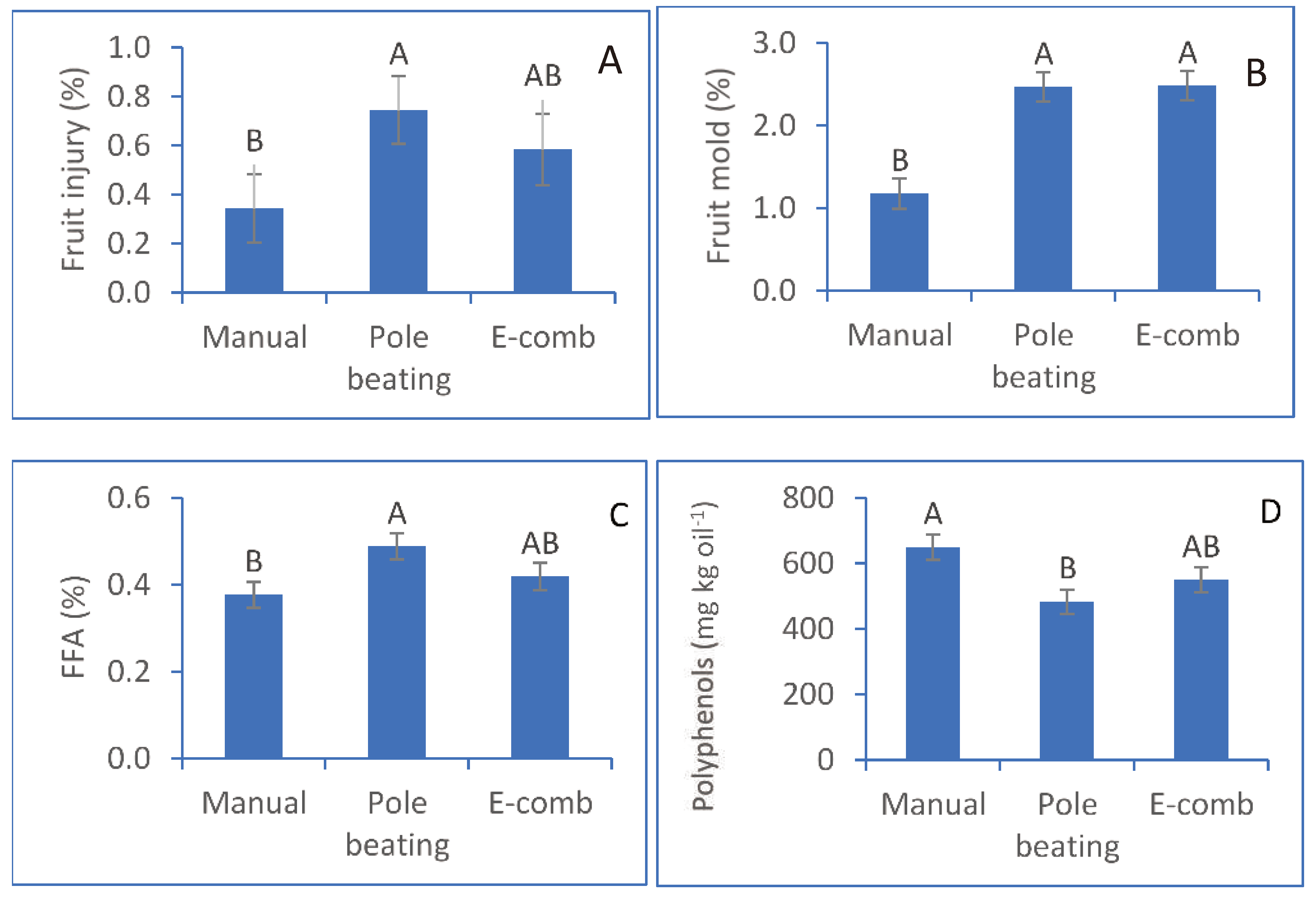

In this experiment, we aimed to separate the harvesting stage from the commercial oil-production chain to understand its role in oil-quality degradation. Manual harvest represents the least disruptive harvesting, used in the first experiment (‘experimental’ harvesting). Pole beating is the commercial method used by the farmers, and the electric comb is a more modern method of fruit harvesting that saves on labor.

The fruit that were harvested by pole beating were significantly more injured than the manually harvested fruit (74.5% vs. 38.6%, respectively), whereas electric-comb harvesting resulted in an intermediate value of 58.3% injured fruit (

Figure 4A). Moreover, fruit mold was more than double with the pole-beating and electric-comb harvesting methods compared to the manual method (

Figure 4B). FFA levels were significantly higher in the oil originating from pole-beating-harvested fruit (0.49%) compared to manual harvesting (0.38%); electric-comb harvesting resulted in an intermediate value of 0.42% (

Figure 4C). All treatments met the EVOO standard. Commercial harvesting (pole beating) also caused a reduction in polyphenols in the oil, from 648.8 mg kg

-1 oil (manual harvesting) to 482.3 mg kg

-1 oil. Electric-comb harvesting resulted in an intermediate level of 549.4 mg kg

-1 oil.

The harvesting method barely affected the contents of secondary metabolites in the oils (

Figure 5). Carotenoids, tocopherols and phytosterols were not significantly affected by the harvesting methods, whereas chlorophyll content was significantly higher in oils obtained from fruit harvested by the electric comb (

Figure 5A).

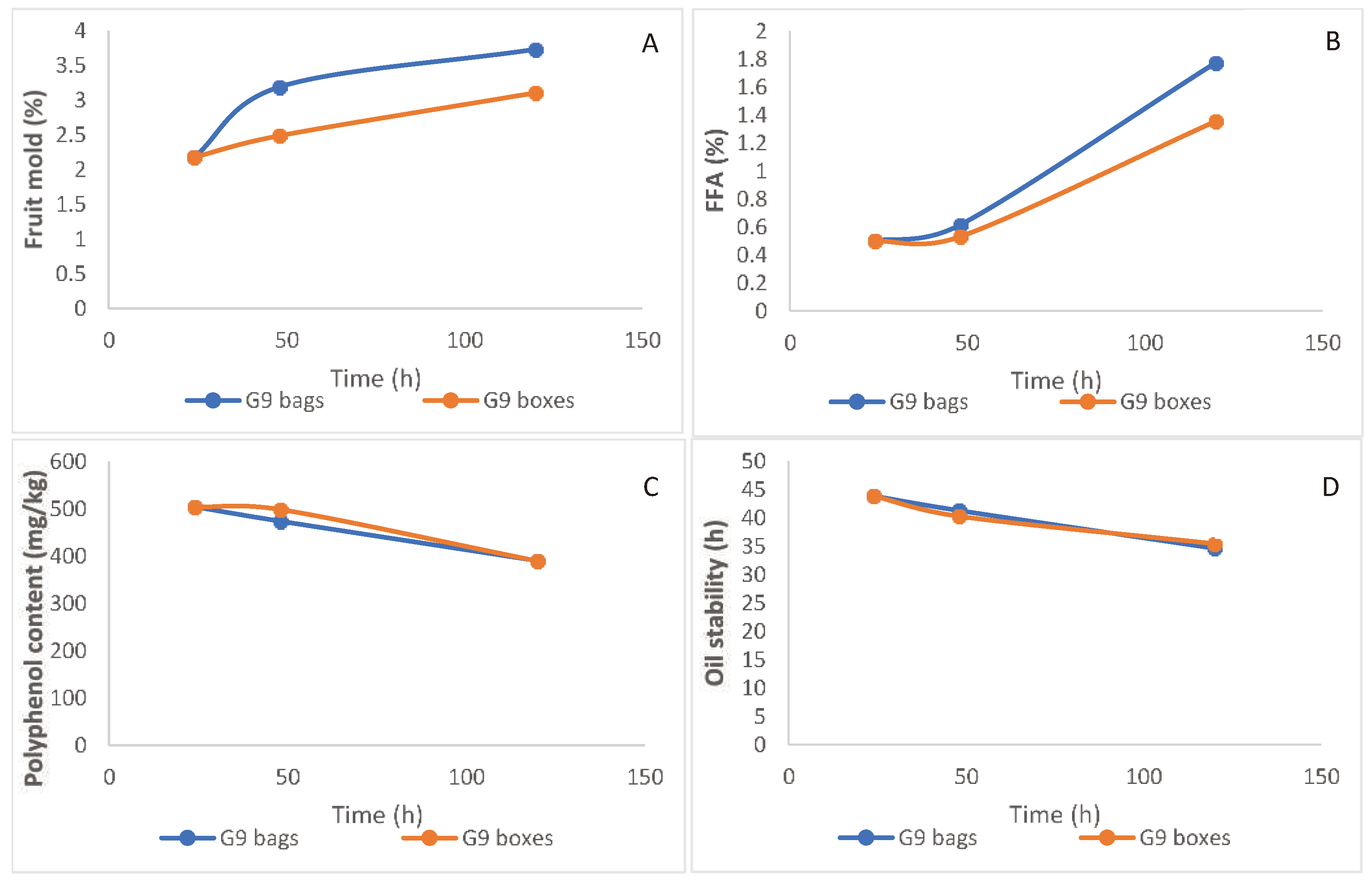

3.3. Effect of fruit storage

Mold was more prevalent in fruit stored in plastic bags (

Figure 6A). FFA levels in the extracted oil increased for 48 h, and then increased sharply toward 120 h storage of the fruits; this deterioration process was faster for fruit stored in bags vs. ventilated boxes (

Figure 6B). Polyphenols in the extracted oil decreased gradually with no difference between fruit-storage methods (

Figure 6C), and similar trends were observed with oil stability (

Figure 6D).

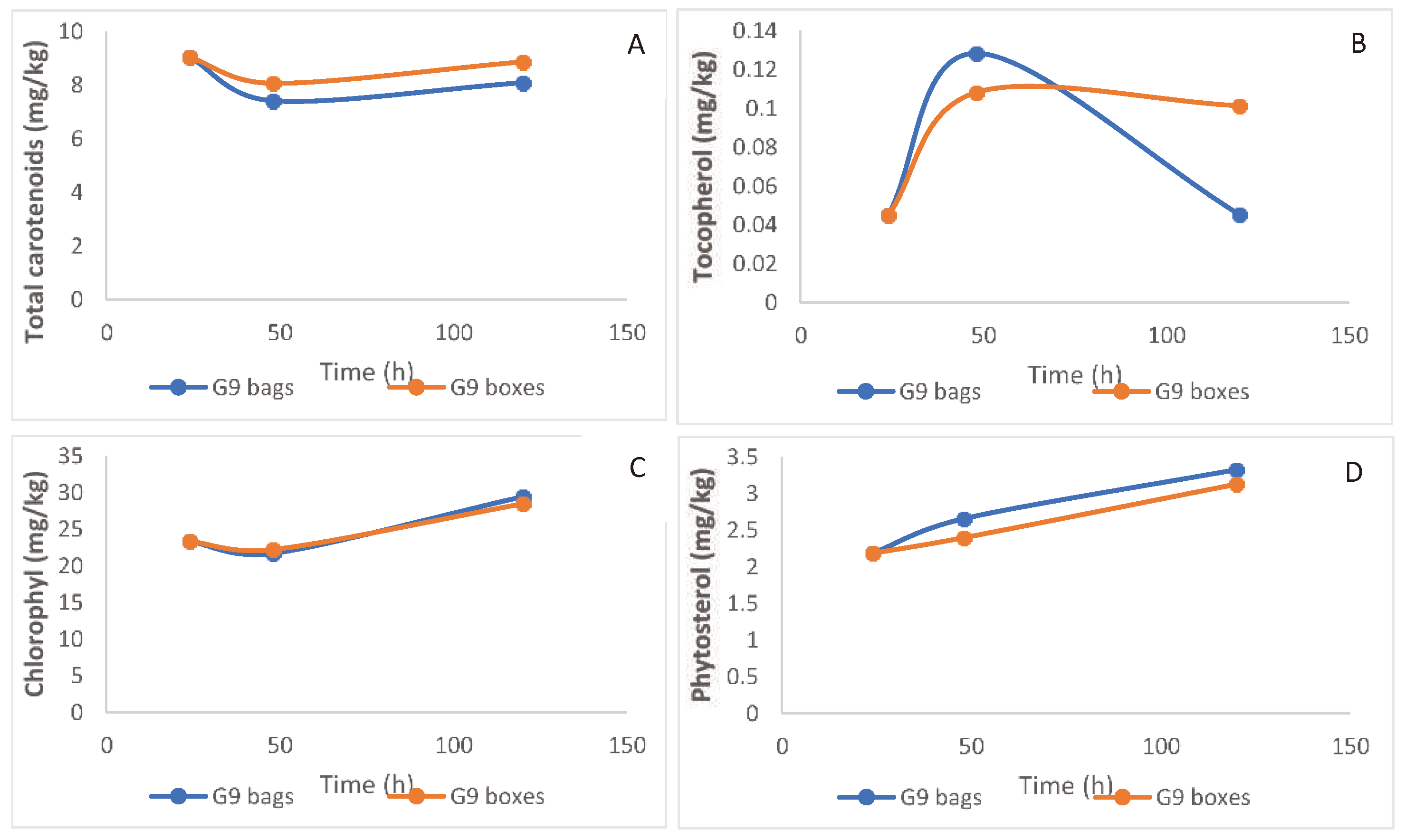

Total carotenoids in the oil decreased slightly with length of fruit storage, this reduction being more pronounced for the bagged fruit (

Figure 7A). The negative impact of storage in bags compared to boxes was highly pronounced for tocopherol, decreasing to a third of its initial level, and significantly lower than when fruit were stored for 120 h (

Figure 7B). Chlorophyll levels in the oil increased slightly with fruit storage, with no difference between bags and boxes (

Figure 7C). Phytosterols also increased during fruit storage, with slightly higher values for the bags (

Figure 7D).

4. Discussion

Various different factors contribute to the reduction of VOO quality along the production chain: orchard management [

24]—e.g., high irrigation levels [

25] and over-fertilization with nitrogen [

26], harvesting—where the method might harm the fruit and reduce oil quality [

27], the time elapsed between harvesting and milling [

28] and the oil-extraction method [

29]. Here, we clearly show good potential for the traditional olive orchards to produce high-quality oil; the FFA and sensory assessment values indicate that the oil can be classified as EVOO. However, as shown in Figs. 2B, 2C, 2D, 3A and

Table 3, the growers’ practices result in much lower oil quality, which does not meet the extra virgin quality standards.

Seeking the ‘bottlenecks’ in farmers’ practices that lead to the reduction in oil quality, we isolated two components in the production chain: harvesting method and fruit storage. Regarding harvesting methods, pole beating, which is the prevalent commercial harvesting method, was found to cause substantial fruit injury (

Figure 4A) and lead to an increase of fruit with mold (

Figure 4B), resulting in reduced polyphenol (

Figure 4D) and increased FFA (

Figure 4C) levels in the oil compared to manual picking. Hence, the commercial harvesting practice contributes to oil-quality deterioration. Using electric combs for harvesting resulted in somewhat better oil quality (

Figure 4), but not significantly so because this method also damages the fruit. The negative impact of aggressive olive harvesting on oil quality has been described in the past [

27,

30]. Regarding fruit storage prior to oil extraction, we evaluated two problems that are prevalent among the traditional growers: one is delayed shipment of the fruit to the mill and the other is storing the fruit in non-ventilated bags. Our results indicated a steady decline in polyphenol content (

Figure 6C) and oil stability (

Figure 6D) along storage. There was a minor increase in FFA levels of oil extracted from fruit stored for up to 48 h, followed by rapid deterioration resulting in a sharp increase in FFA values (

Figure 6B), which was further accelerated in fruit stored in bags. Tocopherols also decreased sharply in fruit stored for a long period in bags (

Figure 7B). Indeed, un-ventilation played a crucial role in attaining the critical threshold at which aerobic respiration shifts to anaerobic fermentative metabolism through the reductive decarboxylation of pyruvate to ethanol. This process induces the development of negative chemical and sensorial attributes in olive oil [

31].

European Regulation 432/2012 distinguishes olive oils in terms of their effect on health, which depends on their polyphenol content (Commission Regulation, EU 2012). The oils in this study were characterized by relatively high levels of polyphenols (

Figure 2C,

Figure 4D and

Figure 6C), more than 250 mg kg

-1 oil, and can thus be classified as “health-protecting food products.” Polyphenols contribute to the oil’s stability and shelf life [

32], as well as to its sensory characteristics [

33] and health properties [

34]. The high level of polyphenols in traditional orchards is due to the water stress, which enhances polyphenol synthesis. Water stress has been previously shown to increase the activity of enzymes, including L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, responsible for the synthesis of phenolic compounds [

35].

In the current study, we focused on traditional rainfed orchards. Those orchards are generally owned by smallholders and have been grown for generations by the same families, a situation that makes it difficult to introduce new cultivation techniques—which have been widely adopted in the intensive olive cultivation practice—that can improve olive oil quality. Although the results of this study indicate specific means that might improve oil quality in traditional olive orchards, their implementation remains socially and culturally challenging [

36].

5. Conclusions

Olive oil produced from rainfed, traditional orchards in the Middle East has potentially high value due to its high content of bioactive polyphenols and the potential of branding it as PDO EVOO. However, the current study shows that olive growers of traditional orchards in the region apply incorrect practices that reduce the oil’s quality. This includes fruit injury caused by aggressive harvesting and long storage of the fruit in unventilated bags. To ensure the future existence of those valuable (to heritage and landscape) orchards, educating the olive growers and improving the production chain will allow them to market high-quality PDO EVOO, increasing their profitability and resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and Z.T.; methodology, I.Z.; software, Z.T.; validation, I.Z. and A.D.; formal analysis, Z.T.; investigation, I.Z.; resources, A.D. and Z.T.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, Z.T. and I.Z.; visualization, I.Z.; supervision, A.D.; project administration, Z.T.; funding acquisition, Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MERC Fund (Middle East Regional Cooperation), grant number M35-027.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Gilat Research Center, Yulia Subbotin, Izabela Galilov, Sarit Melamed and Talal Huashla for technical support in the laboratory and in the field. Special thanks to the growers and mill owners who collaborated with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive compounds and quality of extra virgin olive oil. Foods 2020, 28, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.D.; Ellis, A.C.; Gámbaro, A.; Barrera-Arellano, D. Sensory evaluation of high-quality virgin olive oil: panel analysis versus consumer perception. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 21, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Ortega, A.J.; Remón-Ruiz, P.J.; Piñar-Gutiérrez, A.; Pereira-Cunill, J.L.; García-Luna, P.P. Therapeutic properties and use of extra virgin olive oil in clinical nutrition: a narrative review and literature update. Nutrients 2022, 31, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancausa-Millan, G.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Huete-Alcocer, N. Olive oil as a gourmet ingredient in contemporary cuisine. A gastronomic tourism proposal. Int. J. Gastron. Food. Sci. 2022, 29, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancausa Millán, M.G.; Sanchez-Rivas García, J.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. The olive grove landscape as a tourist resource in Andalucía: oleotourism. Land 2023, 12, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, M.; Avanzato, D.; Caballero, J.M.; Chartzoulakis, K.; Vita Serman, F.; Perry, E. Following Olive Footprints (Olea europaea L.) – Cultivation and Culture, Folklore and History, Tradition and Uses. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), the Association of Agricultural Research Institutions in the Near East and North Africa (AARINENA) and the International Olive Council (IOC), 2012.

- Beaufoy, G.; Baldock, D.; Clark, J. The Nature of Farming: Low Intensity Farming Systems in Nine European Countries. Institute for European Environmental Policy, London, 1994.

- Duarte, F.; Jones, N.; Fleskens, L. Traditional olive orchards on sloping land: sustainability or abandonment? J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 89, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola-Guirado, R.R.; Castro-García, S.; Blanco-Roldán, G.L.; Jiménez-Jiménez, F.; Castillo-Ruiz, F.J.; Gil-Ribes, J.A. Traditional olive tree response to oil olive harvesting technologies. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 118, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, P. Olive oil: history, production, and characteristics of the world’s classic oils. HortScience 2007, 42, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazani, O.; Dag, A.; Dunseth, Z. The history of olive cultivation in the southern Levant. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 2023. 14, 1131557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, E.; Stanley, D.J.; Sharvit, J.; Weinstein-Evron, M. Evidence for earliest olive-oil production in submerged settlements off the Carmel coast, Israel. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langgut, D.; Cheddadi, R.; Carrión, J.S.; Cavanagh, M.; Colombaroli, D.; Eastwood, W.J.; Greenberg, R.; Litt, T.; Mercuri, A.M.; Miebach, A.; Roberts, C.N. The origin and spread of olive cultivation in the Mediterranean Basin: the fossil pollen evidence. Holocene 2019, 29, 902–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langgut, D.; Garfinkel, Y. 7000-year-old evidence of fruit tree cultivation in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, S.; Singer, A.; Haskal, A.; Avidan, B.; Avidan, N.; Wonder, M. Diversity in performance between trees within the traditional Souri olive cultivar (Olea europea L.) in Israel under rain-fed conditions. Oliva 2008, 109, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Barazani, O.; Westberg, E.; Hanin, N.; Dag, A.; Kerem, Z.; Tugendhaft, Y.; Hmidat, M.; Hijawi, T.; Kadereit, J.W. A comparative analysis of genetic variation in rootstocks and scions of old olive trees – a window into the history of olive cultivation practices and past genetic variation. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballco, P.; Gracia, A. Do market prices correspond with consumer demands? Combining market valuation and consumer utility for extra virgin olive oil quality attributes in a traditional producing country. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101999. [Google Scholar]

- Zipori, I.; Bustan, A.; Kerem, Z.; Dag, A. Olive paste oil content on a dry weight basis (OPDW): an indicator for optimal harvesting time in modern olive orchards. Grasas Aceites 2016, 67, e137. [Google Scholar]

- Tietel, Z.; Dag, A.; Yermiyahu, U.; Zipori, I.; Beiersdorf, I.; Krispin, S.; Ben-Gal, A. Irrigation-induced salinity affects olive oil quality and health-promoting properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019; 99, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, T.; Hillis, W. The phenolic constituents of Prunus domestica. I.—The quantitive analysis of phenolic constituents. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1959, 10, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, M.; Aranda, F.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Fregapane, G. Cornicabra virgin olive oil: a study of five crop seasons. Composition, quality and oxidative stability. Food Chem. 2001, 74, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.B.D.C.; Silva, S.L.; Galvão, M.A.M.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Araújo, E.L.; Randau, K.P.; Soares, L.A.L. Total phytosterol content in drug materials and extracts from roots of Acanthospermum hispidum by UV-VIS spectrophotometry. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2013, 23, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Timms, R.; Goh, E. Colorimetric determination of total tocopherols in palm oil, olein and stearin. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 1988, 65, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustan, A.; Kerem, Z.; Yermiyahu, U.; Ben-Gal, A.; Lichter, A.; Droby, S.; Zchori-Fein, E.; Orbach, D.; Zipori, I.; Dag, A. Preharvest circumstances leading to elevated oil acidity in ‘Barnea’ olives. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 176, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, A.; Naor, A.; Ben-Gal, A.; Harlev, G.; Zipori, I.; Schneider, D.; Birger, R.; Peres, M.; Gal, Y.; Kerem, Z. The effect of water stress on super-high-density ‘Koroneiki’ olive oil quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2016–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erel, R.; Kerem, Z.; Ben-Gal, A.; Dag, A.; Schwartz, A.; Zipori, I.; Basheer, L.; Yermiyahu, U. Olive (Olea europaea L.) tree nitrogen status is a key factor for olive oil quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11261–11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dag, A.; Ben-Gal, A.; Yermiyahu, U.; Basheer, L.; Nir, Y.; Kerem, Z. The effect of irrigation level and harvest mechanization on virgin olive oil quality in a traditional rain-fed ‘Souri’ olive orchard converted to irrigation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 1524–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, A.; Boim, S.; Sobotin, Y.; Zipori, I. Effect of mechanically harvested olive storage temperature and duration on oil quality. HortTechnology 2012, 22, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, E.; Kerem, Z.; Zipori, I.; Weissbein, S.; Basheer, L.; Bustan, A.; Dag, A. Optimization of the Abencor system to extract olive oil from irrigated orchards. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 112, 1158–1165.

- Famiani, F.; Farinelli, D.; Urbani, S.; Al Hariri, R.; Paoletti, A.; Rosati, A.; Esposto, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Taticchi, A.; Servili, M. Harvesting system and fruit storage affect basic quality parameters and phenolic and volatile compounds of oils from intensive and super-intensive olive orchards. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasquy, E.; Florido, M.C.; Sola-Guirado, R.R.; García Martos, J.M.; García Martín, J.F. Effect of temperature and time on oxygen consumption by olive fruit: empirical study and simulation in a non-ventilated container. Fermentation 2001, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, F.; Arnaud, T.; Garrido, A. Contribution of polyphenols to the oxidative stability of virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 15, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servili, M.; Esposto, S.; Fabiani, R.; Urbani, S.; Taticchi, A.; Mariucci, F.; Selvaggini, R.; Montedoro, G.F. Phenolic compounds in olive oil: antioxidant, health and organoleptic activities according to their chemical structure. Inflammopharmacology 2009, 17, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, M.J.; Romero, M.P.; Girona, J.; Motilva, M.J. L-Phenyl-alanine ammonia-lyase activity and concentration of phenolics in developing olive (Olea europaea L. cv Arbequina) fruit grown under different irrigation regimes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruz-Carmona, A.; Rosa, M.P.; Colombo, S. Quantification of production inefficiencies as a cost-savings tool for increasing the viability of traditional olive farms. New Medit. 2023, 2, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of the sampled olive orchards.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of the sampled olive orchards.

Figure 2.

(A) Oil content in the dry olive paste in the different orchards (averages of 6 trees per orchard). The vertical red line indicates the 50% value. (B) Free fatty acid (FFA) content in oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes (conducted by the grower). Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P = 0.0023). (C) Polyphenol content in oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes. Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P < 0.0001). (D) Stability of the oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes. Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

(A) Oil content in the dry olive paste in the different orchards (averages of 6 trees per orchard). The vertical red line indicates the 50% value. (B) Free fatty acid (FFA) content in oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes (conducted by the grower). Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P = 0.0023). (C) Polyphenol content in oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes. Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P < 0.0001). (D) Stability of the oils extracted in the laboratory from experimental harvested olives and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes. Differences between treatments are significant (paired observations t-test; P < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Total carotenoid (A), tocopherol (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterol (D) content in the oils extracted experimentally and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes (conducted by the grower).

Figure 3.

Total carotenoid (A), tocopherol (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterol (D) content in the oils extracted experimentally and in oils obtained from the commercial harvest and oil-extraction processes (conducted by the grower).

Figure 4.

Effect of harvest method on fruit injury (A), development of fruit mold (B), oil free fatty acid (FFA) content (C), and oil polyphenol content (D). E-comb, electric comb.

Figure 4.

Effect of harvest method on fruit injury (A), development of fruit mold (B), oil free fatty acid (FFA) content (C), and oil polyphenol content (D). E-comb, electric comb.

Figure 5.

Effect of harvest method on total carotenoids (A), tocopherols (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterols (D) in the oils. E-comb, electric comb.

Figure 5.

Effect of harvest method on total carotenoids (A), tocopherols (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterols (D) in the oils. E-comb, electric comb.

Figure 6.

Effect of olive storage (length and conditions) on fruit mold (A), free fatty acid (FFA) content (B) and polyphenol content (C) in the oil, and oil stability (D).

Figure 6.

Effect of olive storage (length and conditions) on fruit mold (A), free fatty acid (FFA) content (B) and polyphenol content (C) in the oil, and oil stability (D).

Figure 7.

Effect of olive storage (length and conditions) on total carotenoids (A), tocopherols (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterols (D) in the oil.

Figure 7.

Effect of olive storage (length and conditions) on total carotenoids (A), tocopherols (B), chlorophyll (C) and phytosterols (D) in the oil.

Table 1.

Some characteristics of the sampled olive orchards.

Table 1.

Some characteristics of the sampled olive orchards.

Table 2.

Oil fatty acid profile, ratio of monounsaturated to polyunsaturated fatty acids (MUFA/PUFA), and ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids (SFA/UFA) in oils originated from commercial and experimental harvesting in 11 traditional orchards.

Table 2.

Oil fatty acid profile, ratio of monounsaturated to polyunsaturated fatty acids (MUFA/PUFA), and ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids (SFA/UFA) in oils originated from commercial and experimental harvesting in 11 traditional orchards.

Table 3.

Intensity of the positive and negative attributes of the sensory assessment of the oils originated from commercial and experimental harvesting in 11 traditional orchards.

Table 3.

Intensity of the positive and negative attributes of the sensory assessment of the oils originated from commercial and experimental harvesting in 11 traditional orchards.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).