Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Demographics

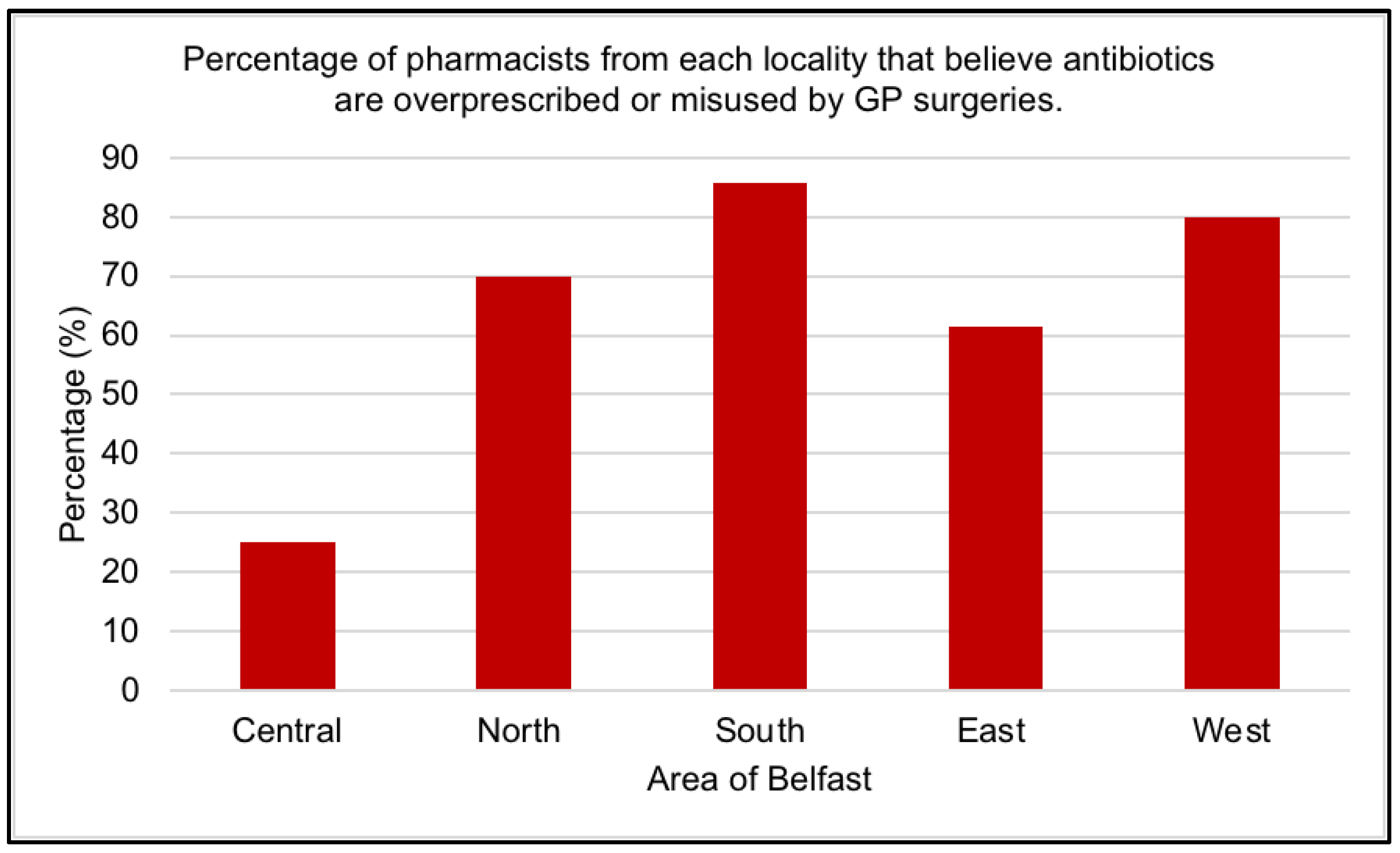

2.2. Misuse of Antibiotics

2.3. Antibiotic use

2.4. What is the problem?

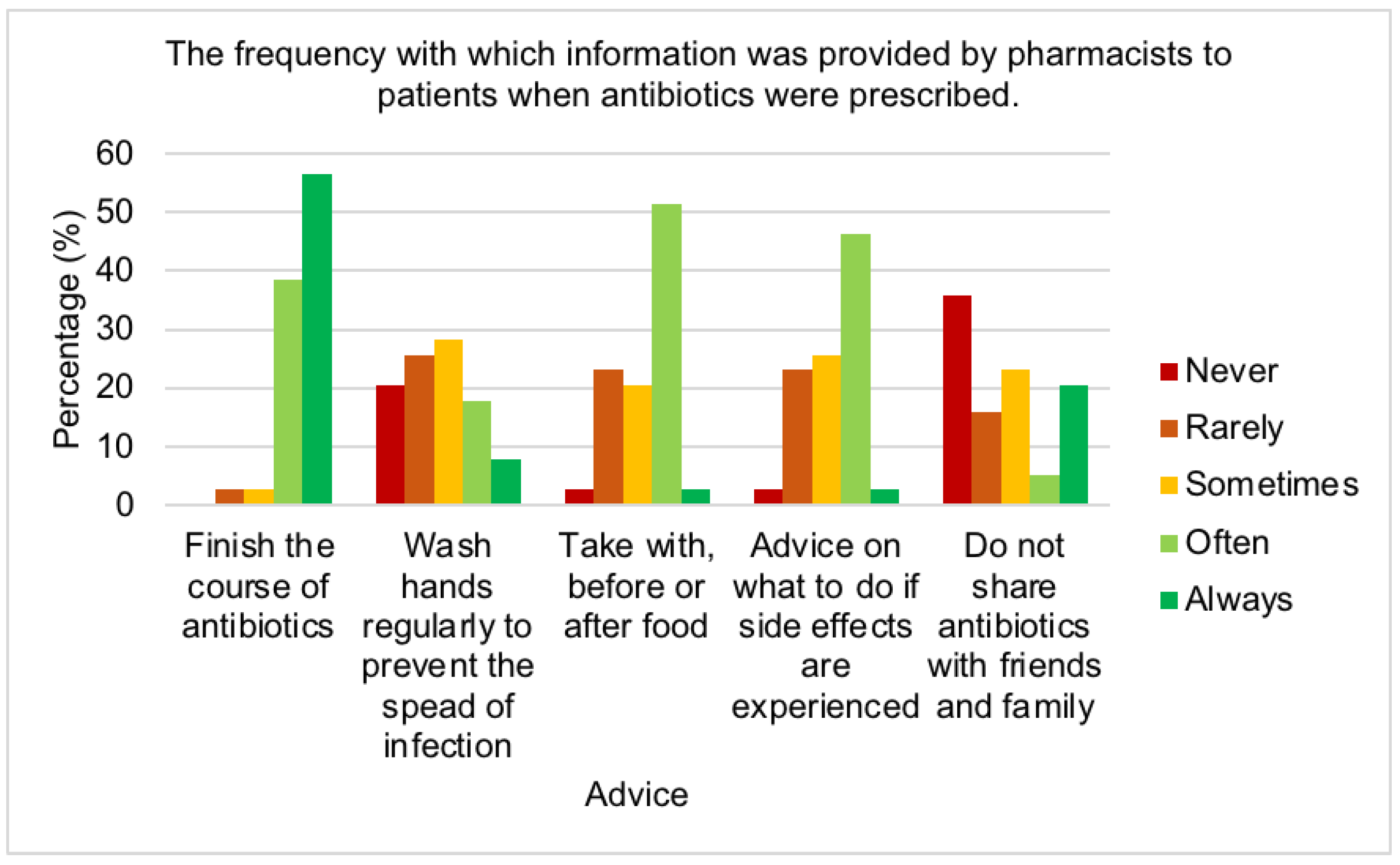

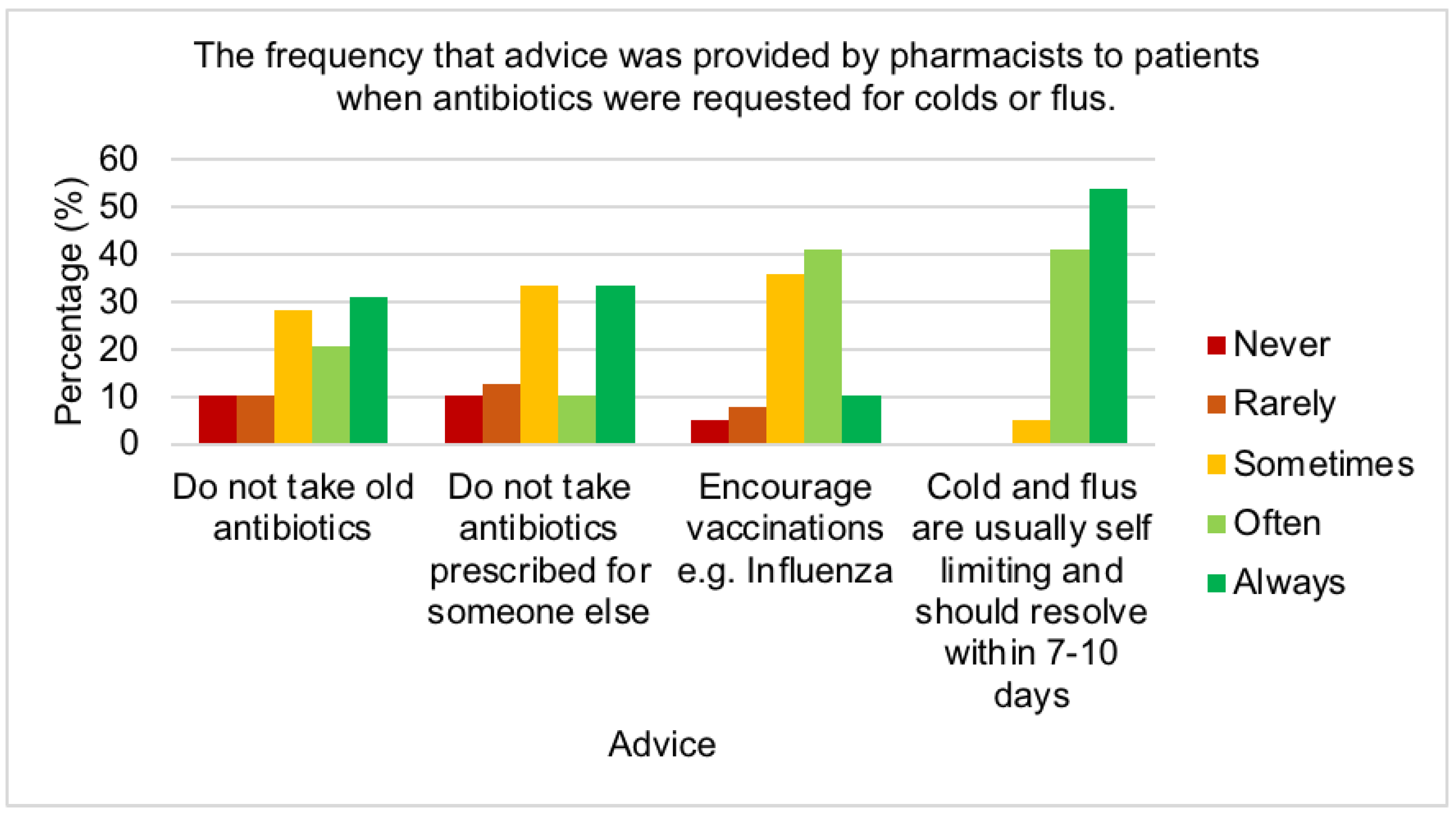

2.5. Reducing antimicrobial resistance

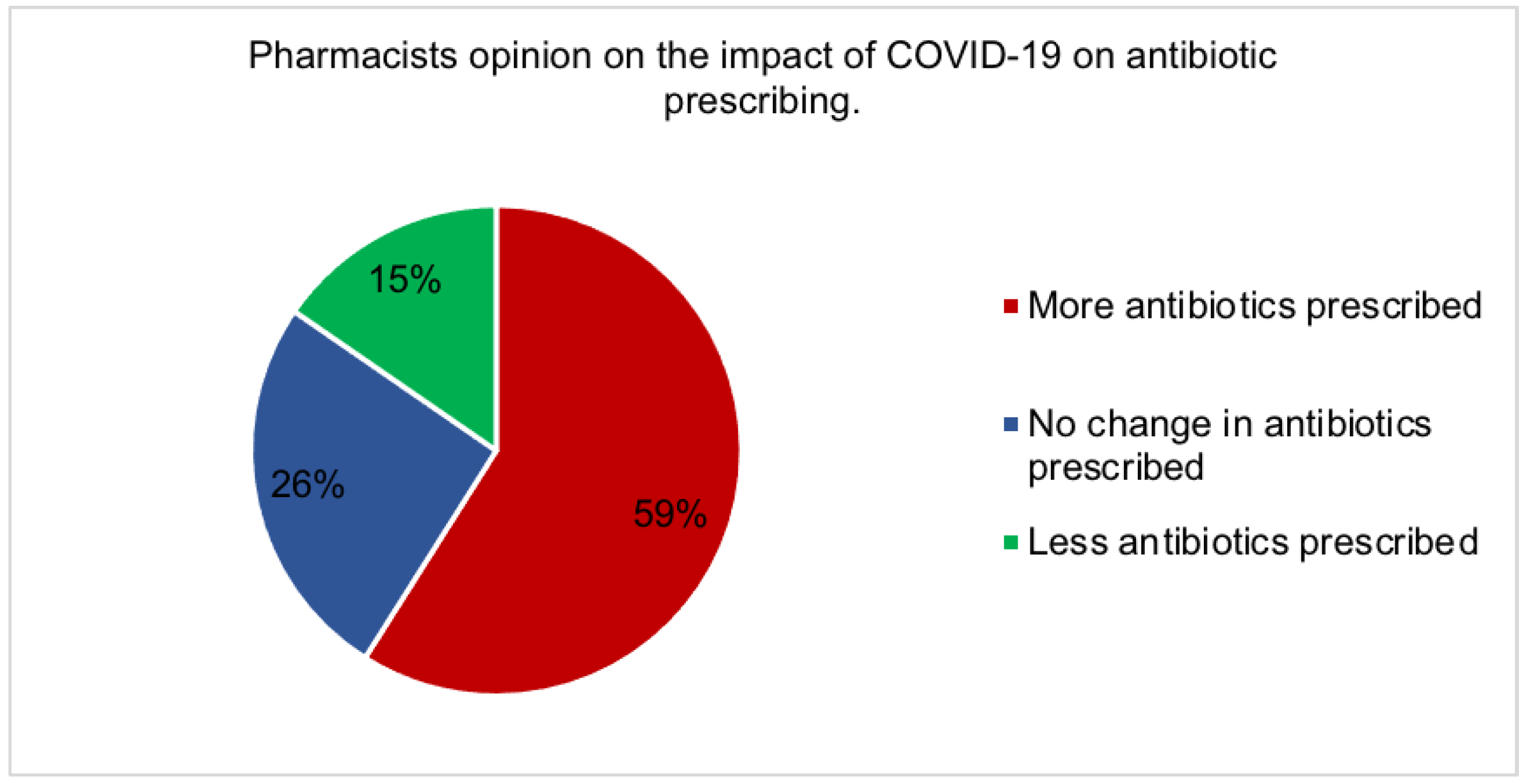

2.6. The effect of covid-19

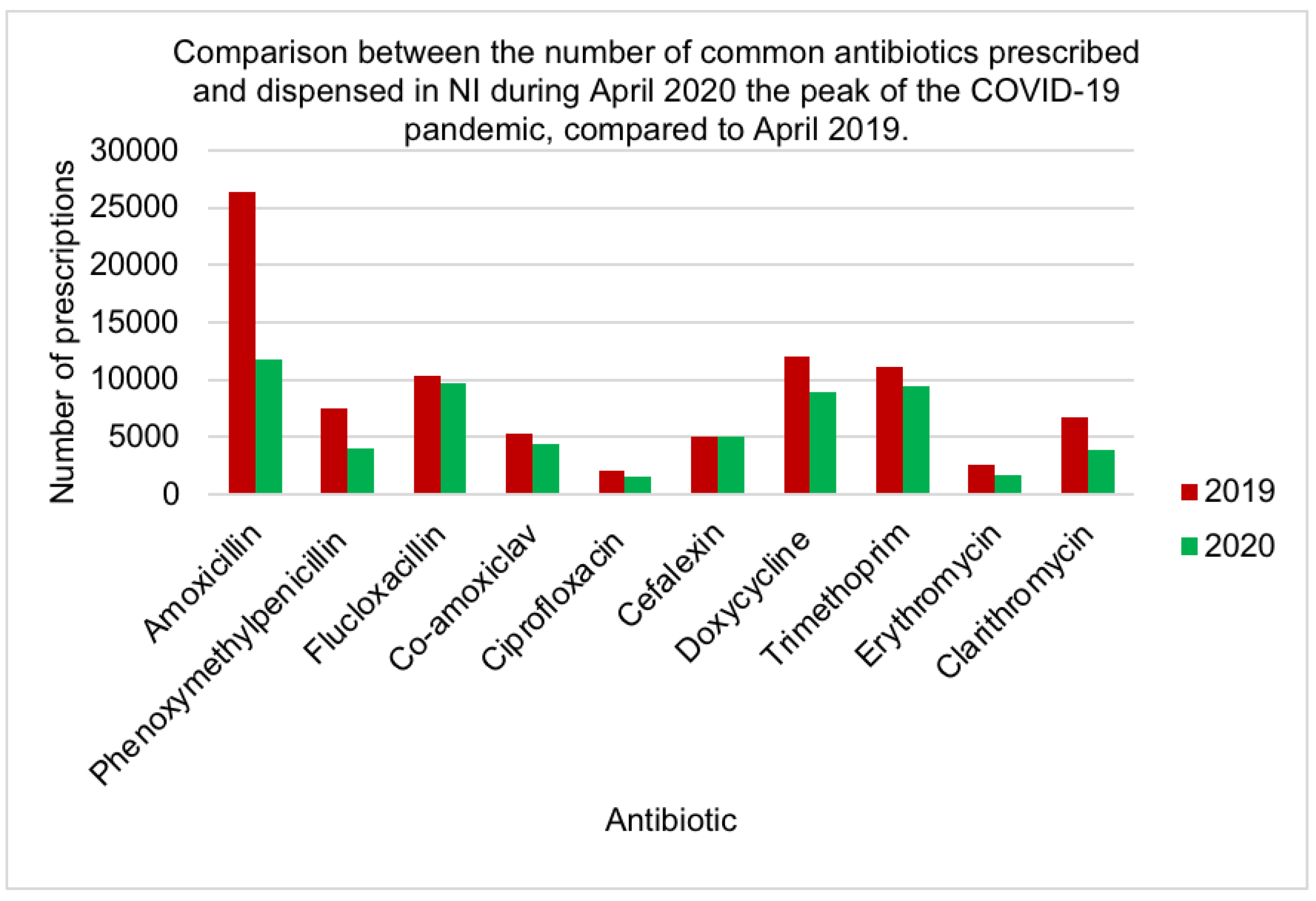

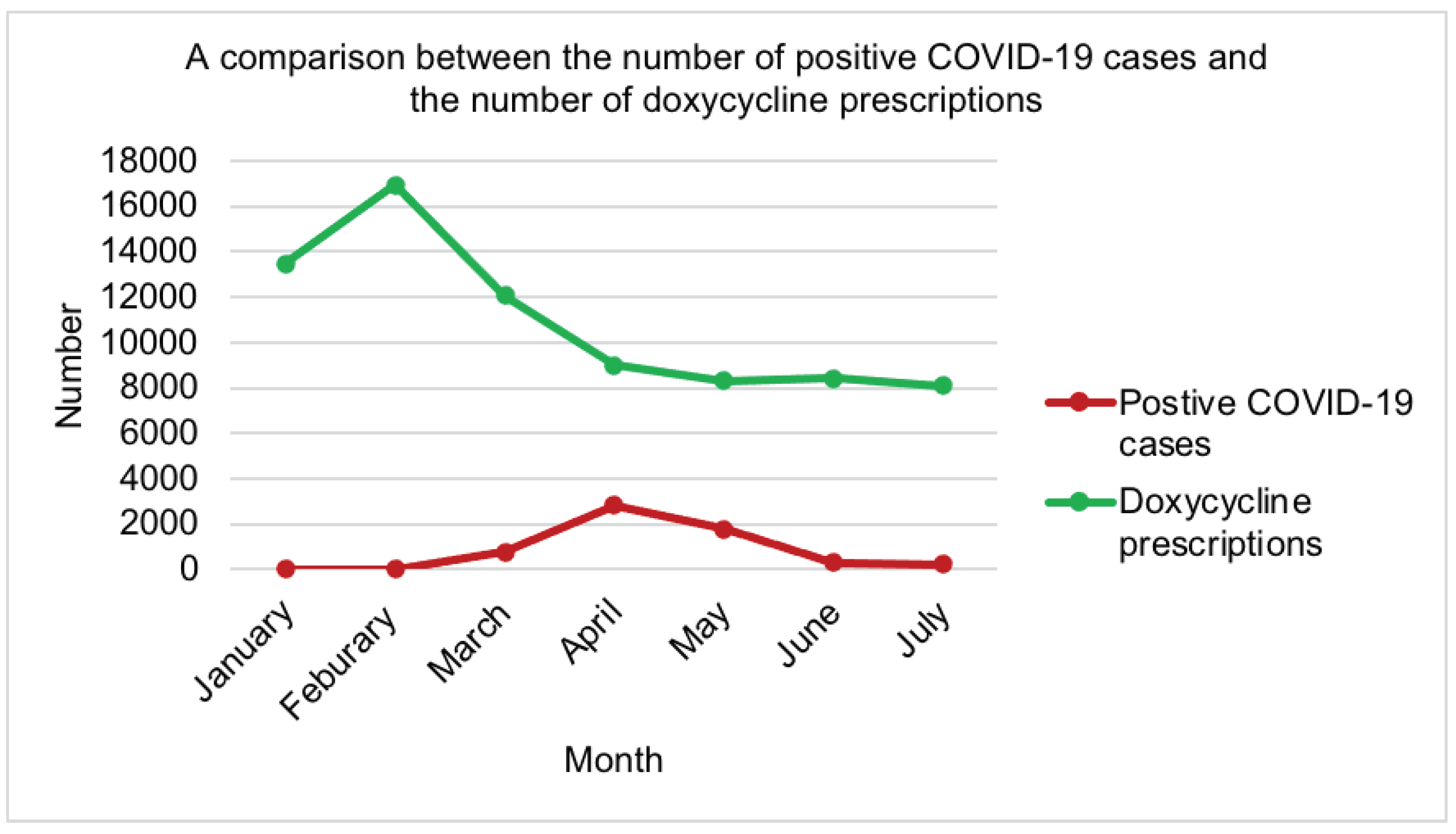

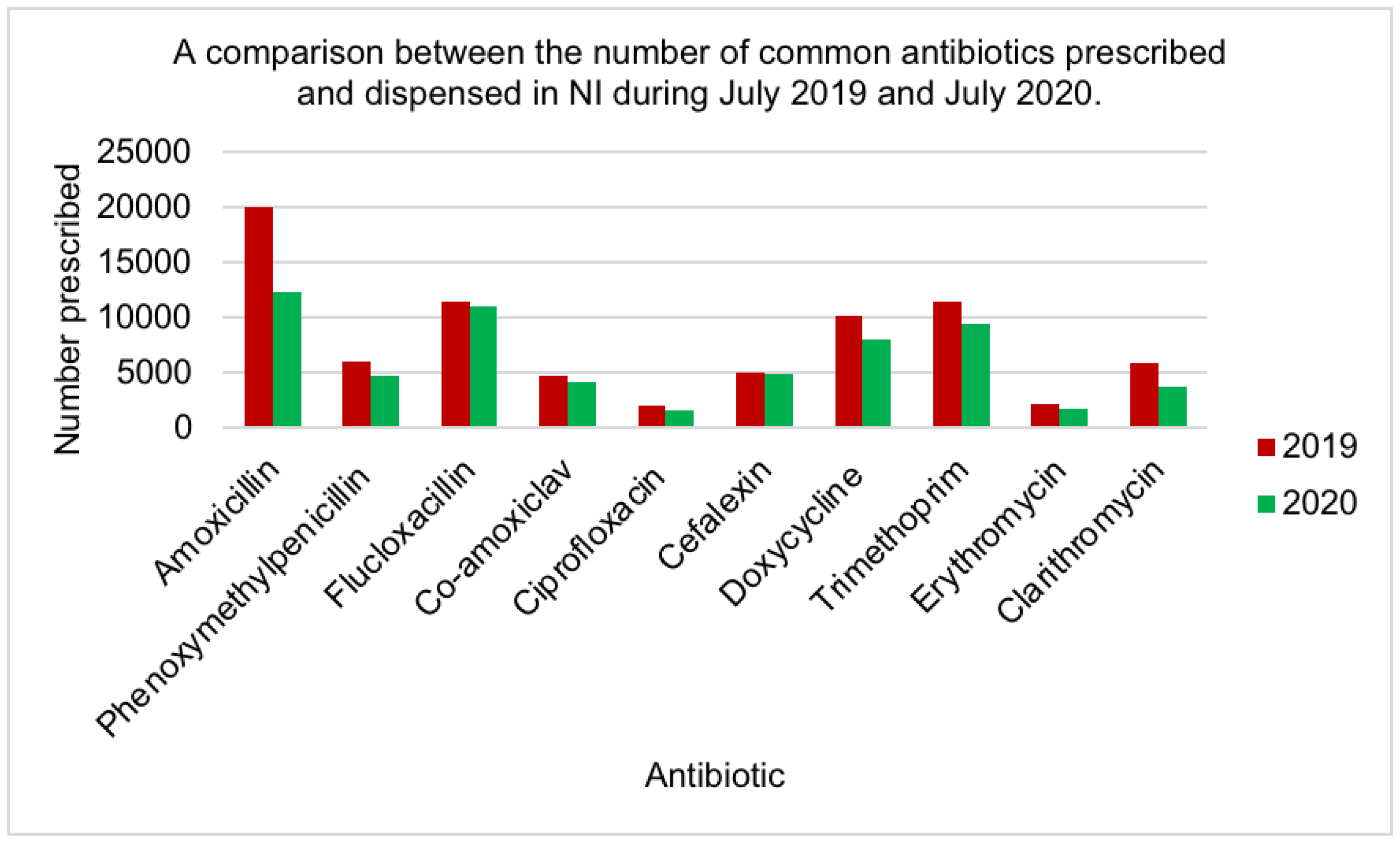

2.7. Prescribing data

2.8. Antibiotic use in the EU

| Country | Consumption of systemic antibacterial agents in primary care (DDD per 1000 inhabitants) | Consumption of systemic antibacterial agents in secondary care (DDD per 1000 inhabitants) |

|---|---|---|

| EU Average | 17.2 | 1.64 |

| UK | 16.3 | 2.47 |

| Ireland | 20.9 | 1.79 |

| Greece | 32.4 | 1.66 |

| Netherlands | 8.9 | 0.84 |

3. Discussion

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Misuse of antibiotics

3.3. Antibiotic Use

3.4. What is the problem?

3.5. Reducing antimicrobial resistance

3.6. The effect of COVID-19

3.7. Antibiotic Use in the EU

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Questionnaire

4.1.1. Development

4.1.2. Piloting

4.1.3. Target Population

4.1.4. Ethical approval

4.1.5. Distribution

4.1.6. Analysis

4.2. Antimicrobial Use in NI

4.2.1. Data Collection

4.2.2. Sample Size

4.2.3. Data Analysis

4.3. Antimicrobial Use in the EU

4.3.1. Data Collection

4.3.2. Sample Size

4.3.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. (2020) Antibiotic resistance. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance [Accessed 28 September 2023].

- World Health Organisation. (2014) Antimicrobial Resistance - Global Report on Surveillance. France: World Health Organisation Press.

- O'Neill, J. (2016) Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report And Recommendations. London.

- Liaskou, M., Duggan, C., Joynes, R. and Rosado, H. (2018) Pharmacy’s role in antimicrobial resistance and stewardship. Clinical Pharmacist, 10(6). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85057974427&site=eds-live.

- Brinkmann, I. and Kibuule, D. (2020) Effectiveness of antibiotic stewardship programmes in primary health care settings in developing countries. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy, 16(9), 1309-1313. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edo&AN=145116808&site=eds-live.

- Rang, H., Ritter, J., Flower, R. and Henderson, G. (2016) Pharmacology. Eighth ed. China: Elsevier.

- Walsh, F. (2013) Antibiotics resistance 'as big a risk as terrorism' - medical chief. BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-21737844 [Accessed 28 September 2023].

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, (ECDC). (2018) 33000 people die every year due to infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/33000-people-die-every-year-due-infections-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria [Accessed 1 October 2023].

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC). (2019) Biggest Threats and Data - 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html [Accessed 30 September 2023].

- House of Commons. (2018) Antimicrobial resistance - Eleventh Report of Session 2017–19. London: House of Commons.

- Clancy, C., Buehrle, D. and Nguyen, H. (2020) PRO: The COVID-19 pandemic will result in increased antimicrobial resistance rates. JAC - Antimicrobial Resistance, 2(3) Available at. [CrossRef]

- Collignon, P. and Beggs, J. (2020) CON: COVID-19 will not result in increased antimicrobial resistance prevalence. JAC - Antimicrobial Resistance, 2(3). Available at. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. (2020) How covid-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. British Medical Journal, 369(8249), m1983. Available at. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. (2015) Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

- Dadgostar, P. (2019) Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect Drug Resist, 12. Available at. [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O., Huttner, B., Schouten, J. and Pulcini, C. (2017) What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 23(11), 793-798. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1198743X17304895&site=eds-live.

- Liaskou, M., Duggan, C., Joynes, R. and Rosado, H. (2018) Pharmacy’s role in antimicrobial resistance and stewardship. Clinical Pharmacist, 10(6). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85057974427&site=eds-live.

- Kesten, J., Bhattacharya, A., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Gobin, M. and Audrey, S. (2017) The Antibiotic Guardian campaign: a qualitative evaluation of an online pledge-based system focused on making better use of antibiotics. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-13. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.850ea28e021e4d06a32a4d1bcb2f310f&site=eds-live.

- Mone, P. (2018) Antibiotic Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in Northern Ireland – What is the problem? Ulster University.

- Business Services Organisation. (2019a) Prescription Cost Analysis. Available at: http://www.hscbusiness.hscni.net/services/3125.htm [Accessed 16 October 2023].

- Business Service Organisation, (BSO). (2019b) GP Prescribing Data. Available at: http://gpdatasets.hscni.net/2019-2020.php [Accessed 8 October 2023].

- Business Services Organisation, (BSO). (2020b) Pharmaceutical list. Available at: http://www.hscbusiness.hscni.net/pdf/OCTOBER%202020%20FULL%20PHARM%20LIST.pdf [Accessed 6 October 2023].

- Gov.uk. (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK - Cases in Northern Ireland. Available at: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/cases?areaType=nation&areaName=Northern%20Ireland [Accessed 12 October 2023].

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). (2020) Antimicrobial consumption database - Rates by country. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/database/rates-country [Accessed 12 October 2023].

- Ebert, J., Huibers, L., Christensen, B. and Christensen, M. (2018) Paper- or Web-Based Questionnaire Invitations as a Method for Data Collection: Cross-Sectional Comparative Study of Differences in Response Rate, Completeness of Data, and Financial Cost. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), 21. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lxh&AN=128677749&site=eds-live.

- Manikkath, J., Matuluko, A., Leong, A., Ching, D., Dewart, C., Lim, R., Meilianti, S. and Uzman, N. (2020) Exploring young pharmacists' and pharmaceutical scientists' needs and expectations within an international pharmacy organization: Findings from FIP's needs assessment survey. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1551741120301728&site=eds-live.

- Saleh, A. and Bista, K. (2017) Examining Factors Impacting Online Survey Response Rates in Educational Research: Perceptions of Graduate Students. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 13(2), 63-74. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=ED596616&site=eds-live.

- Smith, M., Witte, M., Rocha, S. and Basner, M. (2019) Effectiveness of incentives and follow-up on increasing survey response rates and participation in field studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 1-13. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.fe29b9ddf0a42a5aa183e11a1840596&site=eds-live.

- Saliba-Gustafsson, E., Roing, M., Borg, M., Rosales-Klintz, S. and Lundborg, C. (2019b) General practitioners' perceptions of delayed antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract infections: A phenomenographic study. Public Library of Science, 14(11). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edswsc&AN=000533889300034&site=eds-live.

- Palin, V., Mölter, A., Belmonte, M., Ashcroft, D., van Staa, T., White, A. and Welfare, W. (2019) Antibiotic prescribing for common infections in UK general practice: variability and drivers. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 74(8), 2440-2450. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85070116358&site=eds-live.

- Rice, C. (2019) Belfast: Is plan to boost city centre living realistic? Northern Ireland: BBC News.

- Macrotrends. (2020) Belfast, UK Metro Area Population 1950-2020. Available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/206480/belfast/population [Accessed 19 October 2023].

- Fleming, N., Barber, S. and Ashiru-Oredope, D. (2011) Pharmacists have a critical role in the conservation of effective antibiotics. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 287, 465. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/pharmacists-have-a-critical-role-in-the-conservation-of-effective-antibiotics/11086917.article?firstPass=false.

- Allison, R., Lecky, D., Beech, E., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Costelloe, C. and Owens, R. (2020) Local implementation of national guidance on management of common infections in primary care in England: findings of a mixed-methods national questionnaire. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 304(7934). Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/research/research-article/local-implementation-of-national-guidance-on-management-of-common-infections-in-primary-care-in-england/20207599.article.

- Rann, O., Sharland, M., Long, P., Wong, I., Laverty, A., Bottle, A., Barker, C., Bielicki, J. and Saxena, S. (2017) Did the accuracy of oral amoxicillin dosing of children improve after British National Formulary dose revisions in 2014? National cross-sectional survey in England. BMJ Open, 7(9), e016363. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=28954790&site=edslive.

- Iftikhar, S., Sarwar, M., Saqib, A., Sarfraz, M. and Shoaib, Q. (2019) Antibiotic prescribing practices and errors among hospitalized pediatric patients suffering from acute respiratory tract infections: A multicenter, cross-sectional study in Pakistan. Medicina (Lithuania), 55(2). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85061510733&site=eds-live.

- Evans, J., Hannoodee, M. and Wittler, M. (2020) Amoxicillin Clavulanate. In: Anon. Treasure Island (FL). StatPearls Publishing.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020a) Summary of antimicrobial prescribing guidance – managing common infections. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/antimicrobial%20guidance/summary-antimicrobial-prescribing-guidance.pdf [Accessed 27 October 2023].

- Li, Y., Wu, Z., Liu, K., Qi, P., Xu, J., Wei, J., Li, B., Shao, D., Shi, Y., Qiu, Y. and Ma, Z. (2017) Doxycycline enhances adsorption and inhibits early-stage replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in vitro. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 364(17). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85037701578&site=eds-live.

- Kohli, K. (2020) Doxycycline Treatment In High-Risk COVID Patients: Recent Evidence. Available at: https://medicaldialogues.in/pulmonology/perspective/doxycycline-treatment-in-high-risk-covid-patients-recent-evidence-69493?infinitescroll=1 [Accessed 15 October 2020].

- Dolk, F., Pouwels, K., Smith, D., Robotham, J. and Smieszek, T. (2018) Antibiotics in primary care in England: Which antibiotics are prescribed and for which conditions? Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 73. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85042599248&site=eds-live.

- Stuart, B., Brotherwood, H., Van'T Hoff, C., Brown, A., Moore, M., Little, P., Van Den Bruel, A. and Hay, A. (2020) Exploring the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing for common respiratory tract infections in UK primary care. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 75(1), 236-242. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85076447417&site=eds-live.

- Pouwels, K., Dolk, F., Smith, D., Robotham, J. and Smieszek, T. (2018) Actual versus 'ideal' antibiotic prescribing for common conditions in English primary care. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 73, ii19-ii26. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85042594069&site=eds-live.

- Singer, A., Fanella, S., Kosowan, L., Falk, J., Dufault, B., Hamilton, K. and Walus, A. (2018) Informing antimicrobial stewardship: factors associated with inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing in primary care. Family Practice, 35(4), 455-460. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=29237045&site=eds-live.

- Dylis, A., Boureau, A., Coutant, A., Batard, E., François, J., Berrut, G., Decker, L. and Chapelet, G. (2019) Antibiotics prescription and guidelines adherence in elderly: impact of the comorbidities. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 1-6. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.88464458468b4f099dea51ac2618d0bd&site=eds-live.

- Smieszek, T., Pouwels, K., Dolk, F., Smith, D., Robotham, J., Hopkins, S., Sharland, M., Hay, A. and Moore, M. (2018) Potential for reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in English primary care. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 73, ii36-ii43. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85042603084&site=eds-live.

- Krishnakumar, J. and Tsopra, R. (2019) What rationale do GPs use to choose a particular antibiotic for a specific clinical situation? BMC Family Practice, 20(1), 1-9. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.ff6b18c102bb454e8c3476fcffbcd11a&site=eds-live.

- Lewis, C. and Mehmet, M. (2020) Does the NPS® reflect consumer sentiment? A qualitative examination of the NPS using a sentiment analysis approach. International Journal of Market Research, 62(1), 9-17. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=141149888&site=eds-live.

- Mason, T., Trochez, C., Thomas, R., Babar, M., Hesso, I. and Kayyali, R. (2018) Knowledge and awareness of the general public and perception of pharmacists about antibiotic resistance. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-10. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.56e9224543ce42fdbcadb084343999c2&site=eds-live.

- Hayhoe, B., Greenfield, G. and Majeed, A. (2019) Is it getting easier to obtain antibiotics in the UK? The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 69(679), 54-55. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=30704991&site=eds-live.

- Aljayyousi, G., Abdel-Rahman, M., Kurdi, R., El- Heneidy, A. and Faisal, E. (2019) Public practices on antibiotic use: A cross-sectional study among Qatar University students and their family members. Public Library of Science, 14(11). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85075593092&site=eds-live.

- Burns, C. (2017) It’s in our hands: RPS campaign on antimicrobial stewardship encourages good handwashing. The Pharmaceutical Journal, 299(7906). Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/your-rps/its-in-our-hands-rps-campaign-on-antimicrobial-stewardship-encourages-good-handwashing/20203657.article.

- Gardiner, S., Drennan, P., Begg, R., Zhang, M., Green, J., Isenman, I., Everts, R., Chambers, S. and Begg, E. (2018) In healthy volunteers, taking flucloxacillin with food does not compromise effective plasma concentrations in most circumstances. Public Library of Science, 13(7). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.5476a8638c4f73b05e60bf8a057552&site=eds-live.

- Chevalier-Cottin, E., Ashbaugh, H., Brooke, N., Gavazzi, G., Santillana, M., Burlet, N. and Tin Tin Htar, M. (2020) Communicating Benefits from Vaccines Beyond Preventing Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases & Therapy, 9(3), 467-480. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edo&AN=145347693&site=eds-live.

- Ashiru-Oredope, D. (2019) Providing self-care advice for cold and flu keeps antibiotics working. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/opinion/comment/providing-self-care-advice-for-cold-and-flu-keeps-antibiotics-working/20206996.article.

- Catho, G., Centemero, N., Catho, H., Ranzani, A., Balmelli, C., Landelle, C., Zanichelli, V. and Huttner, B. (2020) Factors determining the adherence to antimicrobial guidelines and the adoption of computerised decision support systems by physicians: A qualitative study in three European hospitals. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 141. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1386505620301271&site=eds-live.

- Peters, S., Rowbotham, S., Chisholm, A., Wearden, A., Moschogianis, S., Cordingley, L., Baker, D., Hyde, C. and Chew-Graham, C. (2011) Managing self-limiting respiratory tract infections: a qualitative study of the usefulness of the delayed prescribing strategy. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 61(590), e579-e589. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=22152745&site=eds-live.

- Saliba-Gustafsson, E., Roing, M., Borg, M., Rosales-Klintz, S. and Lundborg, C. (2019) General practitioners' perceptions of delayed antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract infections: A phenomenographic study. Public Library of Science, 14(11). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edswsc&AN=000533889300034&site=eds-live.

- O’Doherty, J., Leader, L., O’Regan, A., Dunne, C., Puthoopparambil, S. and O’Connor, R. (2019) Over prescribing of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections; a qualitative study to explore Irish general practitioners’ perspectives. BMC Family Practice, 20(1), 1-9. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.b3f4b00e17c2436a9d8e0c275d159314&site=eds-live.

- Francis, N., Gillespie, D., Nuttall, J., Hood, K., Little, P., Verheij, T., Goossens, H., Coenen, S. and Butler, C. (2012) Delayed antibiotic prescribing and associated antibiotic consumption in adults with acute cough. British Journal of General Practice, 62(602), 639-646. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=108068735&site=eds-live.

- Spurling, G., Del Mar, C., Dooley, L., Foxlee, R. and Farley, R. (2017) Delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD004417. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=28881007&site=eds-live.

- Kesten, J., Bhattacharya, A., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Gobin, M. and Audrey, S. (2017) The Antibiotic Guardian campaign: a qualitative evaluation of an online pledge-based system focused on making better use of antibiotics. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-13. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.850ea28e021e4d06a32a4d1bcb2f310f&site=eds-live.

- Avent, M., Cosgrove, S., Price-Haywood, E. and van Driel, M. (2020) Antimicrobial stewardship in the primary care setting: from dream to reality? BMC Family Practice, 21(1), 1-9. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.b1b7baf1c8024f2cb8df78cdd905f6c3&site=eds-live.

- Thornton, J. (2020) Covid-19: how coronavirus will change the face of general practice forever. BMJ - British Medical Journal, 368 Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edswsc&AN=000523766600004&site=eds-live.

- Brookes-Howell, L., Hood, K., Cooper, L., Coenen, S., Goossens, H., Little, P., Verheij, T., Godycki-Cwirko, M., Krawczyk, J., Melbye, H., Jakobsen, K., Borras-Santos, A., Worby, P. and Butler, C. (2012) Clinical influences on antibiotic prescribing decisions for lower respiratory tract infection: A nine country qualitative study of variation in care. BMJ Open, 2(3). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-84862223870&site=eds-live.

- MacIntyre, C. and Chau, M. (2017) Pandemics, public health emergencies and antimicrobial resistance - putting the threat in an epidemiologic and risk analysis context. Archives of Public Health, 75(1), 1-6. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.5bd6fe3123fd44ea9a99db0587531973&site=eds-live.

- Seaton, R., Gibbons, C., Cooper, L., Malcolm, W., McKinney, R., Dundas, S., Griffith, D., Jeffreys, D., Hamilton, K., Choo-Kang, B., Brittain, S., Guthrie, D. and Sneddon, J. (2020) Survey of antibiotic and antifungal prescribing in patients with suspected and confirmed COVID-19 in Scottish hospitals. Journal of Infection. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S0163445320306162&site=eds-live.

- Abelenda-Alonso, G., Padullés, A., Rombauts, A., Gudiol, C., Pujol, M., Alvarez-Pouso, C., Jodar, R. and Carratalà, J. (2020) Antibiotic prescription during the COVID-19 pandemic: A biphasic pattern. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 1-2. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=32729437&site=eds-live.

- Corr, S. (2020) GP practices in Northern Ireland still open to patients who need treatment despite perceptions, say chiefs. Belfast Live. Available at: https://www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/health/gp-practices-northern-ireland-still-18891198?cmpredirect= [Accessed 26 October 2023].

- Bostock, N. (2020) Millions of patients 'avoiding calls to GP' during COVID-19 pandemic. GP Online. Available at: https://www.gponline.com/millions-patients-avoiding-calls-gp-during-covid-19-pandemic/article/1681384 [Accessed 26 October 2023].

- National Health Service, (NHS). (2020) Check if you or your child has coronavirus symptoms. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/symptoms/#symptoms [Accessed 26 October 2023].

- Bonzano, C., Borroni, D., Lancia, A. and Bonzano, E. (2020) Doxycycline: From Ocular Rosacea to COVID-19 Anosmia. New insight into the coronavirus outbreak. Frontiers in Medicine, 7. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.11c6830e448b49819e00f38711cb75fc&site=eds-live.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, (NICE). (2020b) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing suspected or confirmed pneumonia in adults in the community. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng165 [Accessed 26 October 2023].

- Karakonstantis, S. and Kalemaki, D. (2019) Antimicrobial overuse and misuse in the community in Greece and link to antimicrobial resistance using methicillin-resistant S. aureus as an example. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 12(4), 460-464. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1876034119301261&site=eds-live.

- Sheldon, T. (2016) Saving antibiotics for when they are really needed: The Dutch example. BMJ, 354. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-84981313709&site=eds-live.

- Nowakowska, M., Van Staa, T., Mölter, A., Ashcroft, D., Tsang, J., Palin, V., White, A. and Welfare, W. (2019) Antibiotic choice in UK general practice: Rates and drivers of potentially inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 74(11), 3371-3378. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85073585306&site=eds-live.

- Tarrant, C., Krockow, E., Nakkawita, D., Bolscher, M., Colman, A., Chattoe-Brown, E., Perera, N., Mehtar, S. and Jenkins, D. (2020) Moral and Contextual Dimensions of “Inappropriate” Antibiotic Prescribing in Secondary Care: A Three-Country Interview Study. Frontiers in Sociology, 5. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.b4b005cb5b64f8986159bf36cdaa5d0&site=eds-live.

- Hardigan, P., Popovici, I. and Carvajal, M. (2016) Response rate, response time, and economic costs of survey research: A randomized trial of practicing pharmacists. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 12(1), 141-148. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1551741115001278&site=eds-live.

- Blair, J., Czaja, R. and Blair, E. (2014) Designing Surveys. A Guide to Decisions and Procedures. 3rd ed. United States of America: SAGE.

- Riiskjaer, E., Ammentorp, J. and Kofoed, P. (2012) The value of open-ended questions in surveys on patient experience: Number of comments and perceived usefulness from a hospital perspective. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 24(5), 509-516. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-84866400644&site=eds-live.

- Rowley, J. (2014) Designing and using research questionnaires: MRN. Management Research Review, 37(3), 308-330. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1508547371?accountid=14775.

- Hoag, J. and Kuo, C. (2016) Ranking question designs and analysis methods. Journal of Medical Statistics and Informatics, 4(6). Available at: http://www.hoajonline.com/journals/pdf/2053-7662-4-6.pdf.

- Smyth, J., Olson, K. and Burke, A. (2018) Comparing survey ranking question formats in mail surveys. International Journal of Market Research, 60(5), 502-516. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=131813217&site=eds-live.

- Taherdoost, H. (2019) What Is the Best Response Scale for Survey and Questionnaire Design; Review of Different Lengths of Rating Scale / Attitude Scale / Likert Scale. Authors International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 8(1), 1-10. https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=229087098105066068000019122027106099098073020038068011091083026111002030074074074027060118002034019104038023064000078095078030020039005023014120118065000073066105119010065042002003090124006100094094115000112013111116125024095103080108096088069079111090&EXT=pdf.

- Hassan, Z., Schattner, P. and Mazza, D. (2006) Doing A Pilot Study: Why Is It Essential? Malaysian Family Physician : The Official Journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia, 1(2-3), 70-73. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=27570591&site=eds-live.

- Boynton, P. (2004) Hands-on guide to questionnaire research: Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 328(7452), 1372. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.41707914&site=eds-live.

- Business Services Organisation, (BSO). (2020a) GP Prescribing Data. Available at: http://gpdatasets.hscni.net/2020-2021.php [Accessed 7 October 2023].

- Eisinga, R., Pelzer, B., Te Grotenhuis, M. and Heskes, T. (2017) Exact p-values for pairwise comparison of Friedman rank sums, with application to comparing classifiers. BMC Bioinformatics, 18(1). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-85011028490&site=eds-live.

- Kim, H. (2017) Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 42(2), 152-155. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.0f4948021d447a8d692c36bec3693d&site=eds-live.

- Dahiru, T. (2008) P - value, a true test of statistical significance? A cautionary note. Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine, 6(1), 21-26. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=25161440&site=eds-live.

- Lewis, C. and Mehmet, M. (2020) Does the NPS® reflect consumer sentiment? A qualitative examination of the NPS using a sentiment analysis approach. International Journal of Market Research, 62(1), 9-17. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=141149888&site=eds-live.

| Antibiotic | Mean Rank | Rank by Friedman test | No of prescriptions in primary care [20] |

Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 1.05 | 1 | 510881 | 1 |

| Doxycycline | 3.55 | 2 | 163572 | 2 |

| Trimethoprim | 3.97 | 4 | 142739 | 3 |

| Flucloxacillin | 4.16 | 5 | 128608 | 4 |

| Phenoxymethyl -penicillin |

3.74 | 3 | 108236 | 5 |

| Clarithromycin | 6.55 | 7 | 97230 | 6 |

| Co-amoxiclav | 6.47 | 6 | 70241 | 7 |

| Cephalexin | 8.82 | 10 | 61303 | 8 |

| Erythromycin | 8.11 | 8 | 31648 | 9 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8.58 | 9 | 24670 | 10 |

| Cause | Mean Rank | Rank by Friedman test |

|---|---|---|

| Overprescribing of antibiotics | 2.62 | 1 |

| Antibiotic overuse or misuse | 3.13 | 2 |

| Inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics | 3.54 | 3 |

| Patient demand on GP | 3.92 | 4 |

| Failure to finish the course of antibiotics | 4.41 | 5 |

| Inappropriate duration of antimicrobial | 5.95 | 6 |

| Incorrect dose of antimicrobial | 6.00 | 7 |

| Sharing antibiotics with friends and family | 7.54 | 8 |

| Poor patient hygiene and sanitation | 7.90 | 9 |

| Opinion | Number of Pharmacists | % of pharmacists |

|---|---|---|

| Useful | 17 | 44 |

| Useful only if changes are made to the current system | 6 | 15 |

| Unhelpful | 16 | 41 |

| Opinion | Number of Pharmacists |

|---|---|

| No effect | 14 |

| Patients are blindly prescribed antibiotics without being examined, which is dangerously altering patients’ expectations on antibiotic use | 11 |

| Patients expect antibiotics | 9 |

| Patients rely more on pharmacy | 4 |

| Unsure | 3 |

| Patients are less likely to contact the GP unless really unwell. | 3 |

| Doxycycline was prescribed to elderly patients awaiting a COVID test | 1 |

| Patients are less likely to demand antibiotics | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).