Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Prevalence of the frailty syndrome in older patients hospitalized in the geriatric ward depending on the diagnostic criteria used,

- Feasibility of diagnostic scales of frailty syndrome in hospitalized patients, sensitivity and specificity of particular criteria in diagnosing frailty syndrome.

- Compatibility between the diagnostic scales used for frailty syndrome.

- Association of frailty, disability, and multimorbidity in patients hospitalized in a geriatric ward.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and setting characteristics

2.2. Measurements

- −

- sociodemographic—age, sex, education, place of residence (urban/rural), the fact of institutionalization,

- −

- clinical—weight, height, BMI, midarm and calf circumference, chronic diseases (peripheral arterial disease, ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, neoplasm, dementia, parkinsonism, chronic osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic renal disease), medicines taken before hospitalization, nutritional condition (Mini Nutritional Assessment—Short Form [10])

- −

- functional—the ability to perform basic activities of daily living assessed with the Barthel index [11], instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) set with six items of the Duke Older American Resources and Services (OARS) I-ADL [12], the risk of falls assessed with Timed Up and Go Test [13] and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) [14].

- −

- mental—the screening scale AMTS by Hodgkinson (Abbreviated Mental Test Score) was used to assess cognitive functions [15], and in the case of reduced scores—additionally, the Folstein Mental State Examination Short MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination) was performed [16]. The diagnosis of dementia was made based on the overall assessment of the patient combined with an interview with an independent informant, following the recommendations of the team of experts of the Polish Alzheimer’s Society. The assessment of a clinical psychologist was also used. The risk of the depressive syndrome was assessed based on the 15-point GDS Geriatric Depression Scale [17].

2.3. Frailty syndrome assessment

2.3.1. Fried criteria

- unintentional weight loss (>5 kg in 12 months)—data obtained based on the patient’s or caregiver’s interview;

- weakness—assessed based on hand grip strength measured with the SAEHAN DHD-1 hand dynamometer, taking into account gender and BMI value; the hand grip strength was measured twice for each of the upper limbs, and the highest value obtained was taken into account;

- exhaustion—determined based on a negative answer to the question: “Do you feel full of energy?” on the Geriatric Depression Scale;

- gait slowdown—measured by the speed of walking a distance of 15 feet (4.6 m), taking into account the sex and height of the tested person;

- reduced physical activity—based on the 6-point Grimby scale [19], a grade of 4 and higher indicates low physical activity.

2.3.2. Clinical Frailty Scale

2.3.3. Rockwood’s Frailty Index

2.3.4. FRAIL Scale

- Exhaustion—determined based on a negative answer to the question: “Do you feel full of energy?” on the Geriatric Depression Scale;

- Problems with climbing stairs—based on a question in the Barthel scale;

- Problems with walking on a flat surface—based on the question in the Barthel scale;

- Co-occurrence of more than five diseases from the following: ischemic heart disease, arterial hypertension, post-stroke condition, dementia, depression, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, osteoporosis,

- unintentional weight loss (> 5 kg in 12 months)—data obtained from the patient’s or caregiver’s interview.

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.5. Ethics approval

3. Results

3.1. Study cohort characteristics

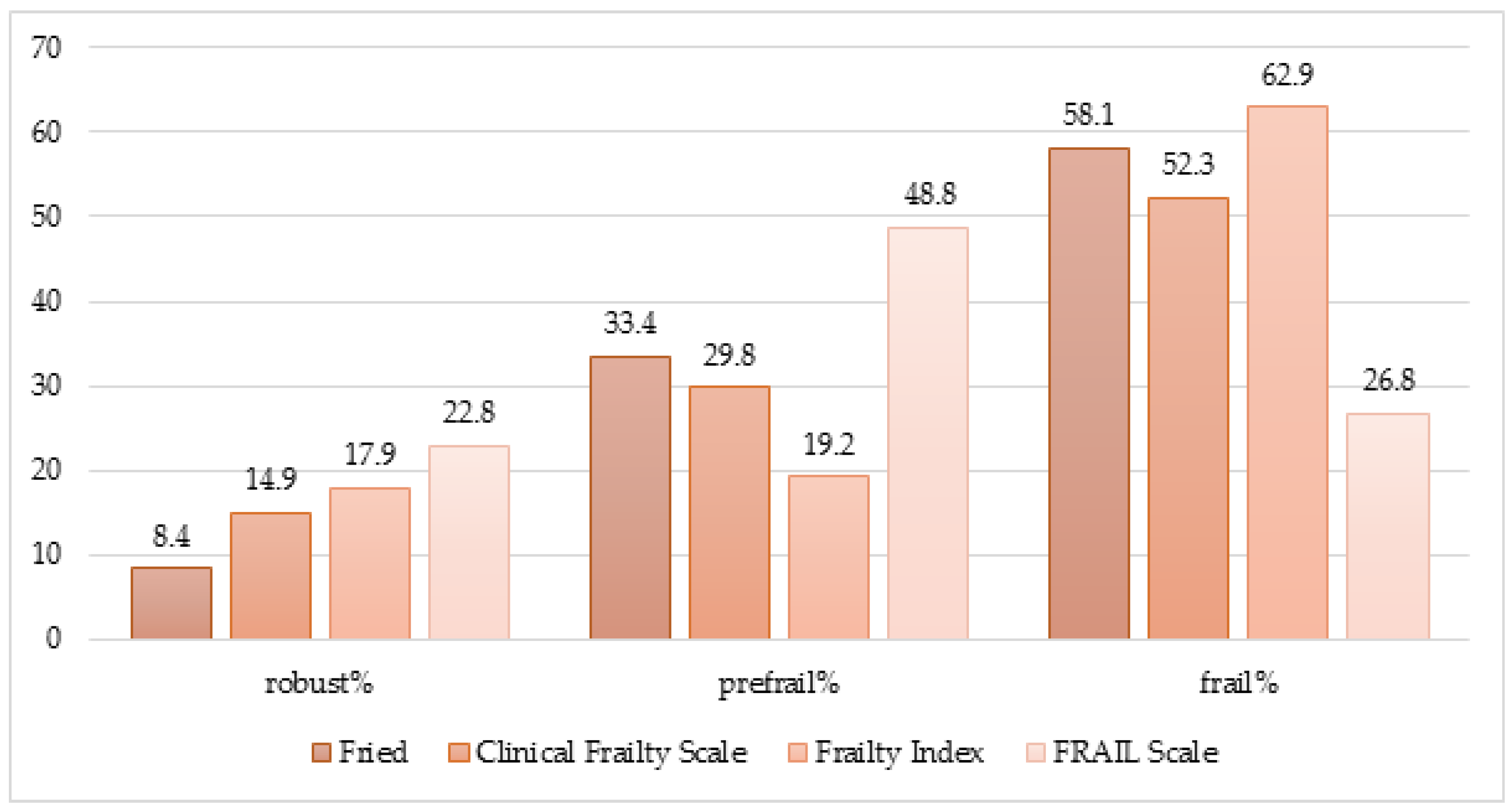

3.2. The frequency of the frailty syndrome depending on the diagnostic criteria and feasibility of the scales

3.2.1. Frailty syndrome diagnosed with Fried criteria

3.2.2. Clinical Frailty Scale

3.2.3. Frailty syndrome by Frailty Index

3.2.4. Frailty syndrome by FRAIL Scale

3.3. Comparison of the diagnostic scales

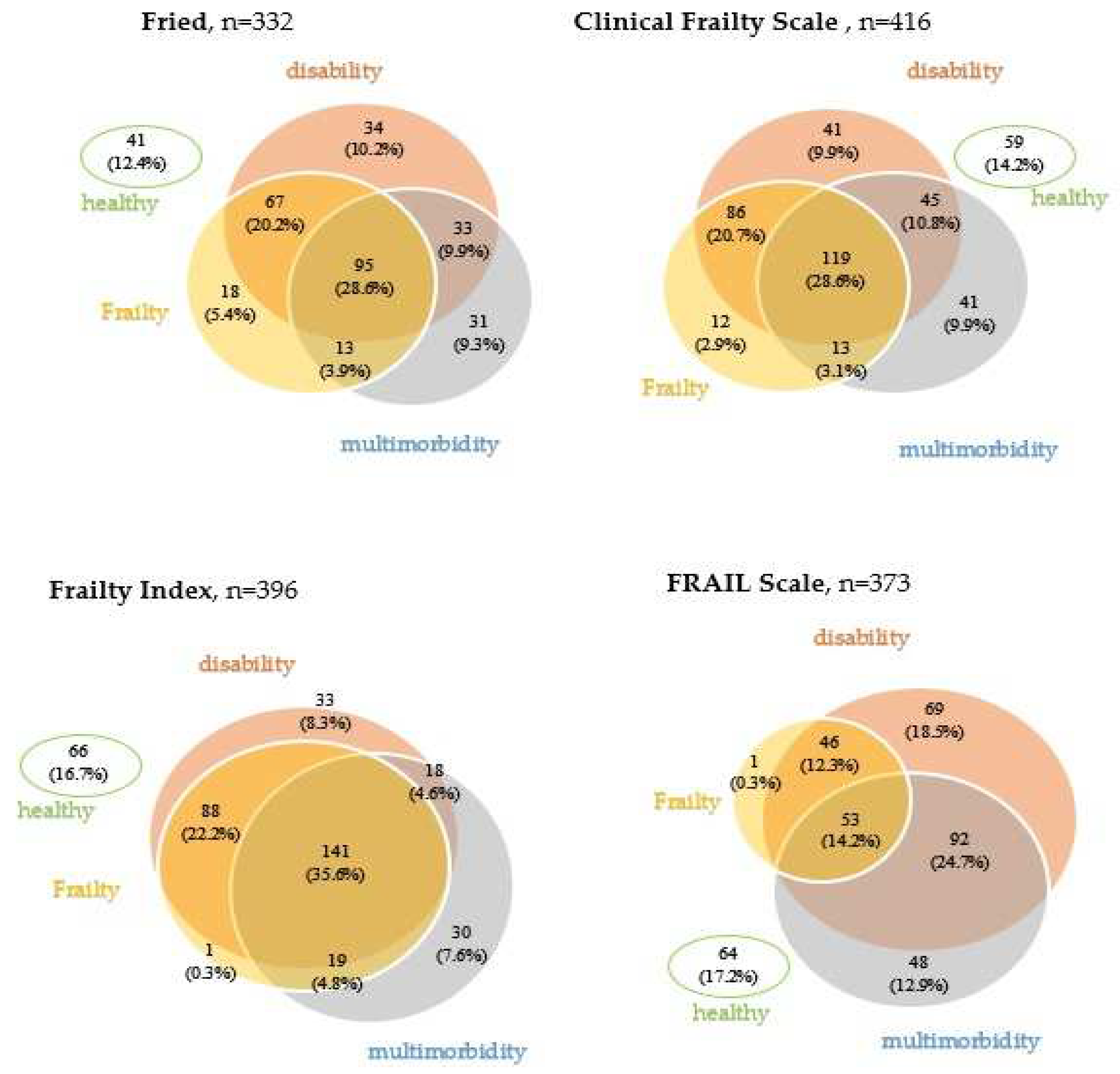

3.2. Frailty, disability, and multimorbidity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A high frequency of frailty syndrome characterizes geriatric ward patients, although the numbers vary depending on the diagnostic criteria. The Frailty Index found the highest incidence and the lowest using the FRAIL scale.

- The feasibility of selected diagnostic scales based on data collected during the comprehensive geriatric assessment in everyday clinical practice differed. The Fried scale was the most difficult to apply (the most missing data, in this case, was observed in measuring walking speed), while the Clinical Frailty Scale could be determined in all patients. Despite the aforementioned diagnostic difficulties, the feasibility of all assessed scales was high.

- Diagnostic scales of the frailty syndrome showed satisfactory agreement—the highest for the Fried and Clinical Frailty Scale and the lowest for the FRAIL with the other scales.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Deficit | Feasibility, n (%) | Prevalence, n (%) | sensitivity(%) | specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

413 (99.3%) | 70 (16.8%) | 24.9 | 100 |

|

412 (99%) | 115 (27.6%) | 42.2 | 99.3 |

|

413 (99.3%) | 80 (19.2%) | 27.7 | 99.3 |

|

413 (99.3%) | 133 (32%) | 49.8 | 100 |

|

411 (98.8%) | 202 (48.6%) | 73.1 | 94.6 |

|

415 (99.8%) | 123 (29.6%) | 44.6 | 99.3 |

|

411 (98.8%) | 184 (44.2%) | 63.1 | 89.1 |

|

413 (99.3%) | 137 (32.9%) | 50.2 | 98.7 |

|

411 (98.8%) | Urine or stool—151 (36.3%) Urine and stool—47 (11.3%) |

28.2 | 98.3 |

|

405 (97.4%) | 304 (73.1%) | 96.4 | 62.6 |

|

405 (97.4%) | 228 (54.8%) | 81.5 | 89.1 |

|

405 (97.4%) | 279 (67.1%) | 93.6 | 74.8 |

|

408 (98.1%) | 178 (42.8%) | 63.5 | 92.5 |

|

409 (98.3%) | 136 (32.7%) | 49 | 96.6 |

|

409 (98.3%) | 174 (41.9%) | 61 | 91.2 |

|

359 (86.3%) | Rather better—130 (31.3%) Rather worse—159 (38.2%) Much worse—61 (14.7%) |

62.5 | 59.2 |

|

374 (89.9%) | 137 (32.9%) | 44.6 | 83 |

|

373 (89.7%) | 117 (28.1%) | 38.2 | 85 |

|

374 (89.9%) | 112 (26.9%) | 35.7 | 84.3 |

|

368 (88.5%) | sometimes—151 (36.4%) often—95 (22.8%) |

44.6 | 70.1 |

|

386 (92.8%) | 122 (29.5%) | 34.1 | 80.9 |

|

407 (97.8%) | 322 (77.4%) | 83.9 | 32.6 |

|

358 (86.1%) | 157 (43.9%) | 43.4 | 67.3 |

|

416 (100%) | 327 (78.6%) | 78.7 | 20.4 |

|

416 (100%) | 223 (53.6%) | 57.4 | 51.7 |

|

416 (100%) | 39 (9.38%) | 12.1 | 94.6 |

|

416 (100%) | 162 (38.9%) | 47.8 | 76.2 |

|

416 (100%) | 56 (13.5%) | 18.5 | 95.2 |

|

416 (100%) | 126 (30.3%) | 31.3 | 74.8 |

|

416 (100%) | 42 (10.1%) | 10.8 | 90.5 |

|

416 (100%) | 32 (7%) | 7.6 | 93.9 |

|

416 (100%) | 324 (77.9%) | 81.9 | 25.8 |

|

416 (100%) | 74 (17.8%) | 17.3 | 83.7 |

|

416 (100%) | severe-27 (6.5%); moderate-45 (10.8%); mild-64 (15.4%): MCI-44 (10.6%) |

40.6 | 83 |

|

416 (100%) | 55 (13.2%) | 18.5 | 96.6 |

|

318 (76.4%) | 181 (56.9%) | 38.4 | 88.9 |

|

406 (97.6%) | 76 (18.7%) | 19.7 | 83 |

|

337 (81.0%) | 220 (65.3%) | 69.1 | 60.5 |

|

308 (74.0%) | 160 (51.9%) | 55.8 | 81.6 |

|

322 (77.4%) | 199 (61.8%) | 37.4 | 99.3 |

References

- Dent, E.; Martin, F.C.; Bergman, H.; Woo, J.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Walston, J.D. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet 2019, 394, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walston, J.; Hadley, E.C.; Ferrucci, L.; Guralnik, J.M.; Newman, A.B.; Studenski, S.A.; Ershler, W.B.; Harris, T.; Fried, L.P. Research Agenda for Frailty in Older Adults: Toward a Better Understanding of Physiology and Etiology: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Lee, C.S.; Vitale, C.; Manulik, S.; Denfeld, Q.E.; Uchmanowicz, B.; Rosińczuk, J.; Drozd, M.; Jaroch, J.; Jankowska, E.A. Frailty and the risk of all-cause mortality and hospitalization in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. ESC Hear. Fail. 2020, 7, 3427–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, C.; Chai, K.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. Prevalence and prognosis of frailty in older patients with stage B heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Hear. Fail. 2023, 10, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkiewicz, M.; Wojszel, Z.B.; Kasiukiewicz, A.; Magnuszewski, L.; Wojszel, A. Association of Chronic Heart Failure with Frailty, Malnutrition, and Sarcopenia Parameters in Older Patients—A Cross-Sectional Study in a Geriatric Ward. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.-H.; Yu, J.-C.; Hsu, H.-M.; Chu, C.-H.; Hong, Z.-J.; Feng, A.-C.; Fu, C.-Y.; Dai, M.-S.; Liao, G.-S. The impact of frailty on breast cancer outcomes: evidence from analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2005-2018. Am J Cancer Res 2022, 12, 5589–5598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; on behalf of ESCEO and the EUGMS frailty working group; Buckinx, F. ; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bauer, J.; Cederholm, T.; Cherubini, A.; Cooper, C.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; et al. How clinical practitioners assess frailty in their daily practice: an international survey. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 29, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, B.R.d.S.; Luchesi, B.M.; Barbosa, G.C.; Junior, H.P.; Martins, T.C.R.; Gratão, A.C.M. Agreement between fragility assessment instruments for older adults registered in primary health care. 43, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, P.; Asamane, E.A.; Aunger, J.A.; Swales, B.; Lord, J.M.; Greig, C.A.; Whittaker, A.C. The prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty among geriatric hospital inpatients and its association with economic prosperity and healthcare expenditure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 467,779 geriatric hospital inpatients. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 80, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Ramsch, C.; Uter, W.; Guigoz, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Thomas, D.R.; Anthony, P.; Charlton, K.E.; Maggio, M.; et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA®-SF): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal 1965;14:56-61.

- Fillenbaum, G.G.; Smyer, M.A. The Development, Validity, and Reliability of the Oars Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire. J. Gerontol. 1981, 36, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinetti, M.E. Performance-Oriented Assessment of Mobility Problems in Elderly Patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1986, 34, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, H.M. EVALUATION OF A MENTAL TEST SCORE FOR ASSESSMENT OF MENTAL IMPAIRMENT IN THE ELDERLY. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1972, 1, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1983, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimby, G. Physical Activity and Muscle Training in the Elderly. Acta Medica Scand. 1986, 220, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, S.; Rogers, E.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnitski, A.B.; Mogilner, A.J.; Rockwood, K. Accumulation of Deficits as a Proxy Measure of Aging. Sci. World J. 2001, 1, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, F.G.; Theou, O.; Wallace, L.; Brothers, T.D.; Gill, T.M.; A Gahbauer, E.; Kirkland, S.; Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Comparison of alternate scoring of variables on the performance of the frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood K, Abeysundera MJ, Mitnitski A. How should we grade frailty in nursing home patients? 5: J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2007; 8(9), 2007.

- Theou, O.; Brothers, T.D.; Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Operationalization of Frailty Using Eight Commonly Used Scales and Comparison of Their Ability to Predict All-Cause Mortality. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewieczek, J.; Bieniek, J.; Wilczyński, K. Fried frailty phenotype assessment components as applied to geriatric inpatients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, E.; Demuynck, M.; Detroyer, E.; Milisen, K. Prevalence of frailty and its ability to predict in hospital delirium, falls, and 6-month mortality in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielza, R.; Balaguer, C.; Zambrana, F.; Arias, E.; Thuissard, I.J.; Lung, A.; Oñoro, C.; Pérez, P.; Andreu-Vázquez, C.; Neira, M.; et al. Accuracy, feasibility and predictive ability of different frailty instruments in an acute geriatric setting. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Di Carlo, M.; Carotti, M.; Farah, S.; Giovagnoni, A. Frailty prevalence according to the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe-Frailty Instrument (SHARE-FI) definition, and its variables associated, in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: findings from a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 33, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, N.; Teixeira, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Paúl, C. Frailty phenotype criteria in centenarians: Findings from the Oporto Centenarian Study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 5, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, T.; van der Eerden, B.; Rivadeneira, F.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Voortman, T.; Zillikens, M.C. Dietary advanced glycation end-products (dAGEs) intake and its relation to sarcopenia and frailty – The Rotterdam Study. Bone 2022, 165, 116564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stille, K.; Temmel, N.; Hepp, J.; Herget-Rosenthal, S. Validation of the Clinical Frailty Scale for retrospective use in acute care. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Hubbard, R.; Peel, N.M.; Samanta, M.; Gray, L.C.; E Fries, B.; Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Derivation of a frailty index from the interRAI acute care instrument. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studzińska, K.; Wąż, P.; Frankiewicz, A.; Stopczyńska, I.; Studnicki, R.; Hansdorfer-Korzon, R. Employing the Multivariate Edmonton Scale in the Assessment of Frailty Syndrome in Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozicka, I.; Guligowska, A.; Chrobak-Bień, J.; Czyżewska, K.; Doroba, N.; Ignaczak, A.; Machała, A.; Spałka, E.; Kostka, T.; Borowiak, E. Factors Determining the Occurrence of Frailty Syndrome in Hospitalized Older Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Pasieczna, A.H.; Wójta-Kempa, M.; Gobbens, R.J.J.; Młynarska, A.; Faulkner, K.M.; Czapla, M.; Szczepanowski, R. Physical, Psychological and Social Frailty Are Predictive of Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo-Briones, M.; Rodríguez-Laso. ; Carnicero, J.A.; Gryglewska, B.; Sinclair, A.J.; Landi, F.; Vellas, B.; Artalejo, F.R.; Checa-López, M.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L. The ability of eight frailty instruments to identify adverse outcomes across different settings: the FRAILTOOLS project. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turusheva, A.; Frolova, E.; Korystina, E.; Zelenukha, D.; Tadjibaev, P.; Gurina, N.; Turkeshi, E.; Degryse, J.-M. Do commonly used frailty models predict mortality, loss of autonomy and mental decline in older adults in northwestern Russia? A prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan DB, Freifeit EA, Strain LA et al. Comparing frailty measures in their ability to predict adverse outcome among older residents of assisted living. BMC Geriatrics. 2012; 12:56.

- Moloney, E.; O’donovan, M.R.; Sezgin, D.; Flanagan, E.; McGrath, K.; Timmons, S.; O’caoimh, R. Diagnostic Accuracy of Frailty Screening Instruments Validated for Use among Older Adults Attending Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apóstolo, J.; Cooke, R.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Santana, S.; Marcucci, M.; Cano, A.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.; Germini, F.; Holland, C. Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults: an umbrella review of frailty screening tools. JBI Évid. Synth. 2017, 15, 1154–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, C.-L.; Henao, G.-M.; Gomez, F. Frailty among rural elderly adults. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Velilla, N.; Herce, P.A.; Herrero. C.; Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; de Asteasu, M.L.S.; Mateos, A.S.; Zubillaga, A.C.; Beroiz, B.I.; Jiménez, A.G.; Izquierdo, M. Heterogeneity of Different Tools for Detecting the Prevalence of Frailty in Nursing Homes: Feasibility and Meaning of Different Approaches. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 898–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Sex | P | Age | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | <75 years | ≥75 years | ||||

| No. (%) of patients | 416 (100) | 322 (77.4) | 94 (22.6) | 66 (15.9) | 350 (84.1) | ||

| Age, y, M (SD) | 82 (77; 86) | 82 (77; 86) | 82.5 (78; 87) | 0.39 | |||

| Gender, women, n (%) | 54 (81.8) | 268 (76.6) | 0.34 | ||||

| Place of residence (urban), n (%) | 329 (79.1) | 254 (78.9) | 75 (79.8) | 0.84 | 56 (84.9) | 273 (78) | 0.2 |

| Barthel Index, Me (IQR) | 90 (70; 100) |

90 (70; 100) |

95 (70; 100) |

0.07 | 97 (90; 100) |

90 (70; 95) |

<0.001 |

| Duke OARS IADL, Me (IQR) | 7 (3; 11) |

7 (4; 11) |

7 (2; 10) |

0.17 |

10 (7; 12) |

7 (2; 10) |

<0.001 |

| POMA, Me (IQR) | 23 (17; 28) |

23 (17; 28) |

24 (19; 28) |

0.66 | 27.5 (23; 28) |

22.5 (17; 28) |

<0.001 |

| TUG, s, Me (IQR) | 17.4 (11.9; 28) |

18 (12; 28) |

14.7 (11.4; 28.8) |

0.19 | 11.6 (9.5; 17) |

19 (12.7; 30) |

<0.001 |

| Orthostatic hypotension, n (%) | 57 (16.2) |

32 (11.7) |

25 (32.1) |

<0.001 | 8 (14.6) |

49 (16.4) |

0.72 |

| Risk of depression—GDS > 5, n (%) | 181 (56.9) | 148 (58.5) | 33 (50.8) | 0.26 | 32 (62.8) | 149 (55.8) | 0.35 |

| Risk of cognitive impairment—AMTS < 6, n (%) | 111 (29.1) | 88 (29.6) | 23 (27.4) | 0.68 | 5 (8.8) | 106 (32.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of chronic diseases, Me (IQR) | 5 (3; 6) | 4 (3; 6) | 5 (4; 7) | 0.003 | 3.5 (2; 6) | 5 (3; 6) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization in the last year, n (%) | 122 (29.5) | 83 (25.9) | 39 (41.9) | 0.002 | 17 (25.8) | 105 (30.3) | 0.46 |

| Criterion | Feasibility | Prevalence | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fried scale | ||||

| Gait speed | 79.2 | 51.9 | 82.6 | 84.9 |

| Handgrip | 86.6 | 65.3 | 85.6 | 61.9 |

| Exhaustion | 93.1 | 61.6 | 86.7 | 71.7 |

| Weight loss | 97.9 | 18.4 | 28.2 | 90.6 |

| Low physical activity | 98.5 | 73.4 | 96.9 | 61.1 |

| FRAIL scale | ||||

| Inability to walk 100 m | 99.8 | 29.6 | 81.9 | 94.1 |

| Inability to climb stairs | 98.8 | 44.2 | 96.0 | 78.4 |

| Exhaustion | 87.0 | 53.6 | 98.9 | 50.5 |

| Weight loss | 97.6 | 18.3 | 49.0 | 89.7 |

| Multimorbidity | 100 | 7.7 | 13.0 | 90.8 |

| Conformity of qualifications to three categories (robust-prefrail-frail) |

Conformity of qualifications to two categories (non-frail-frail) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of matching answers | Weighted kappa | 95% Cl | % of matching answers | Weighted kappa | 95% Cl | |

| Fried-CFS | 70.2 | 0.49 | 0.45-0.53 | 79.2 | 0.58 | 0.53-0.63 |

| Fried-FI | 68.9 | 0.45 | 0.41-0.49 | 79.6 | 0.58 | 0.52-0.64 |

| CFS-FI | 68.7 | 0.45 | 0.41-0.49 | 80.3 | 0.60 | 0.55-0.65 |

| FRAIL-CFS | 53.1 | 0.29 | 0.26-0.32 | 69.7 | 0.41 | 0.37-0.45 |

| FRAIL-Fried | 48.9 | 0.23 | 0.19-0.27 | 64.9 | 0.35 | 0.31-0.39 |

| FRAIL-FI | 44.8 | 0.20 | 0.17-0.23 | 61.7 | 0.31 | 0.27-0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).