Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

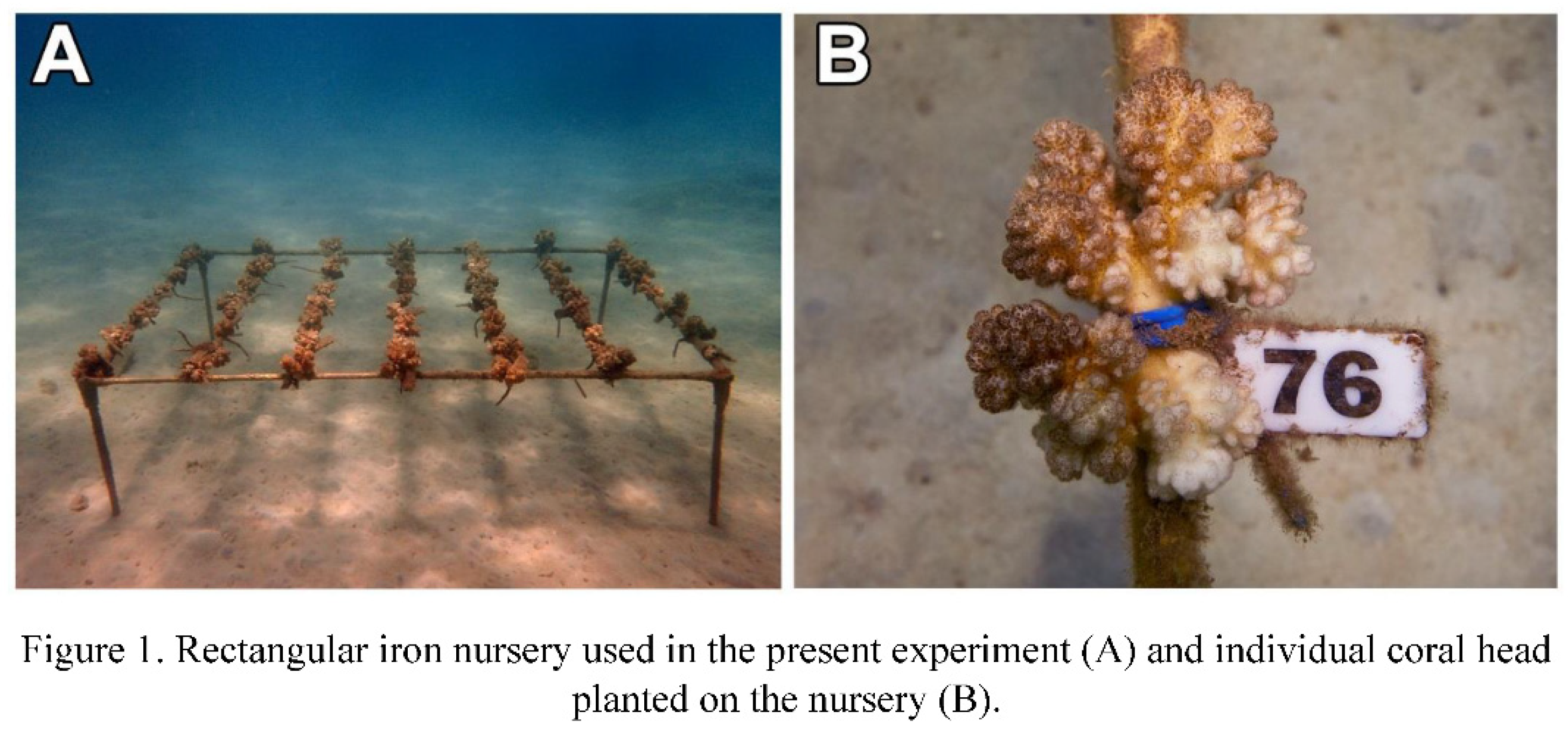

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Studied coral and research location

2.2. Environmental parameters

2.3. Assessment of bleaching and mortality

2.4. Statistical treatment

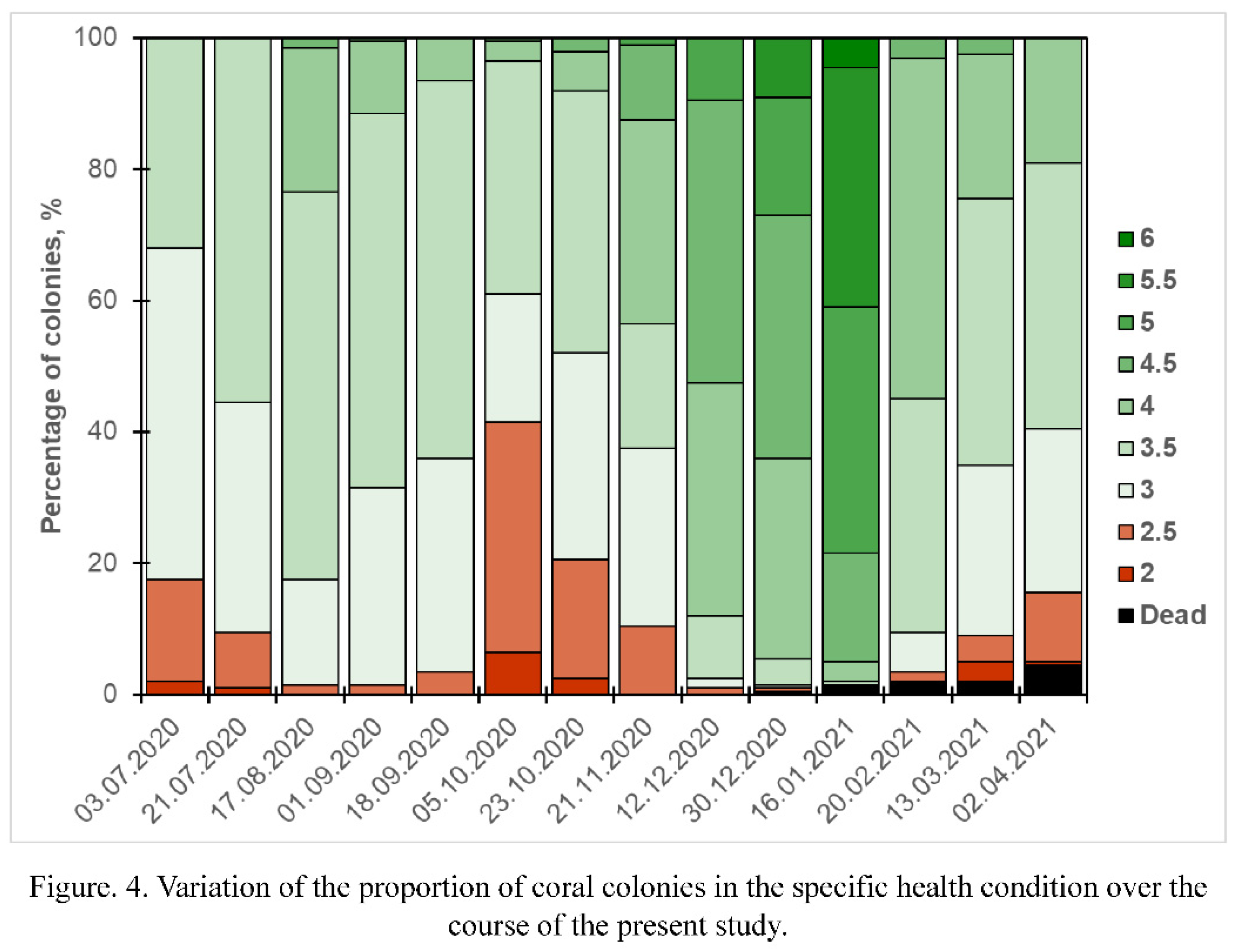

3. Results

3.1. Variation of the environmental factors

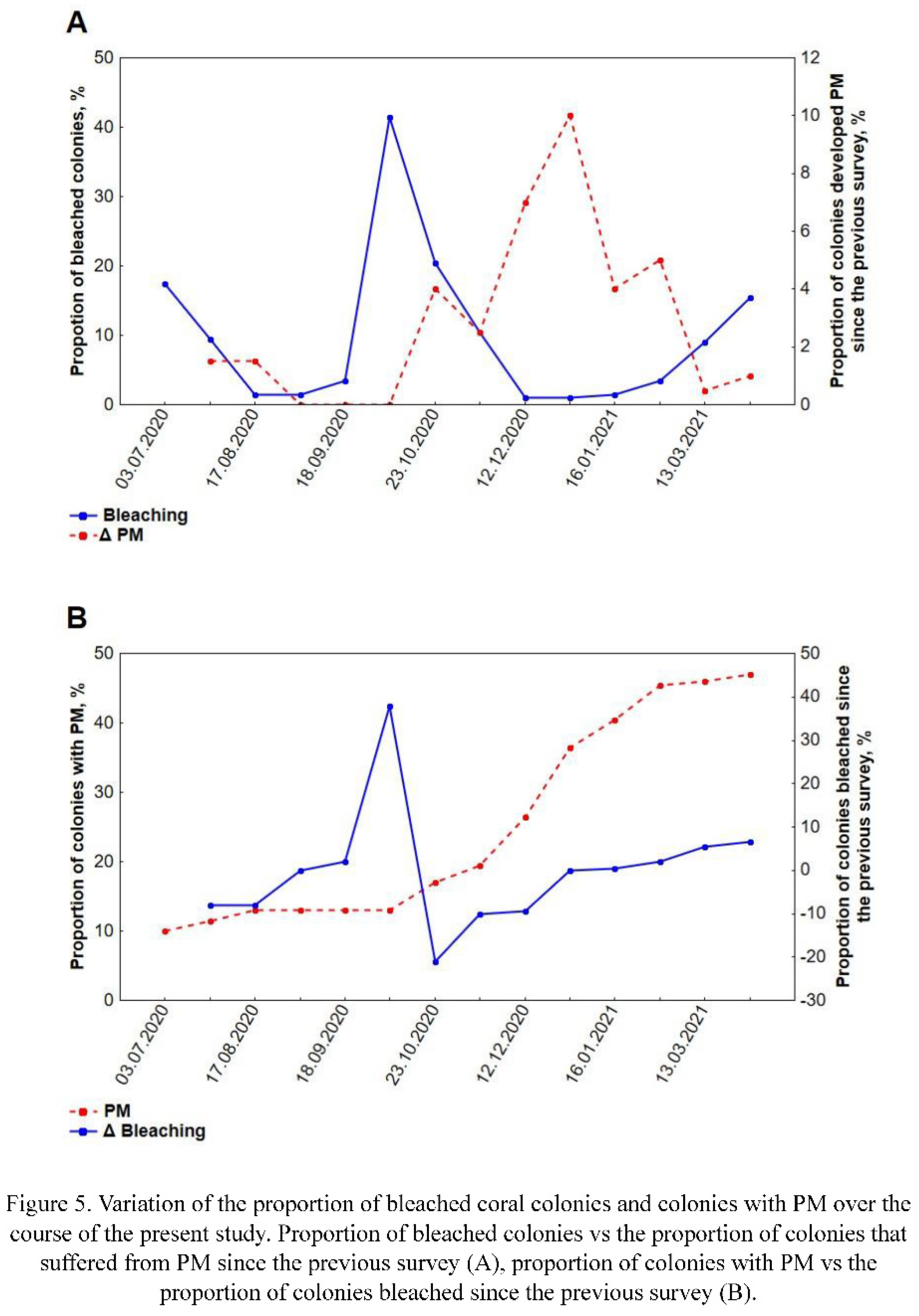

3.2. Bleaching variability

3.3. Partial mortality

3.4. Mortality

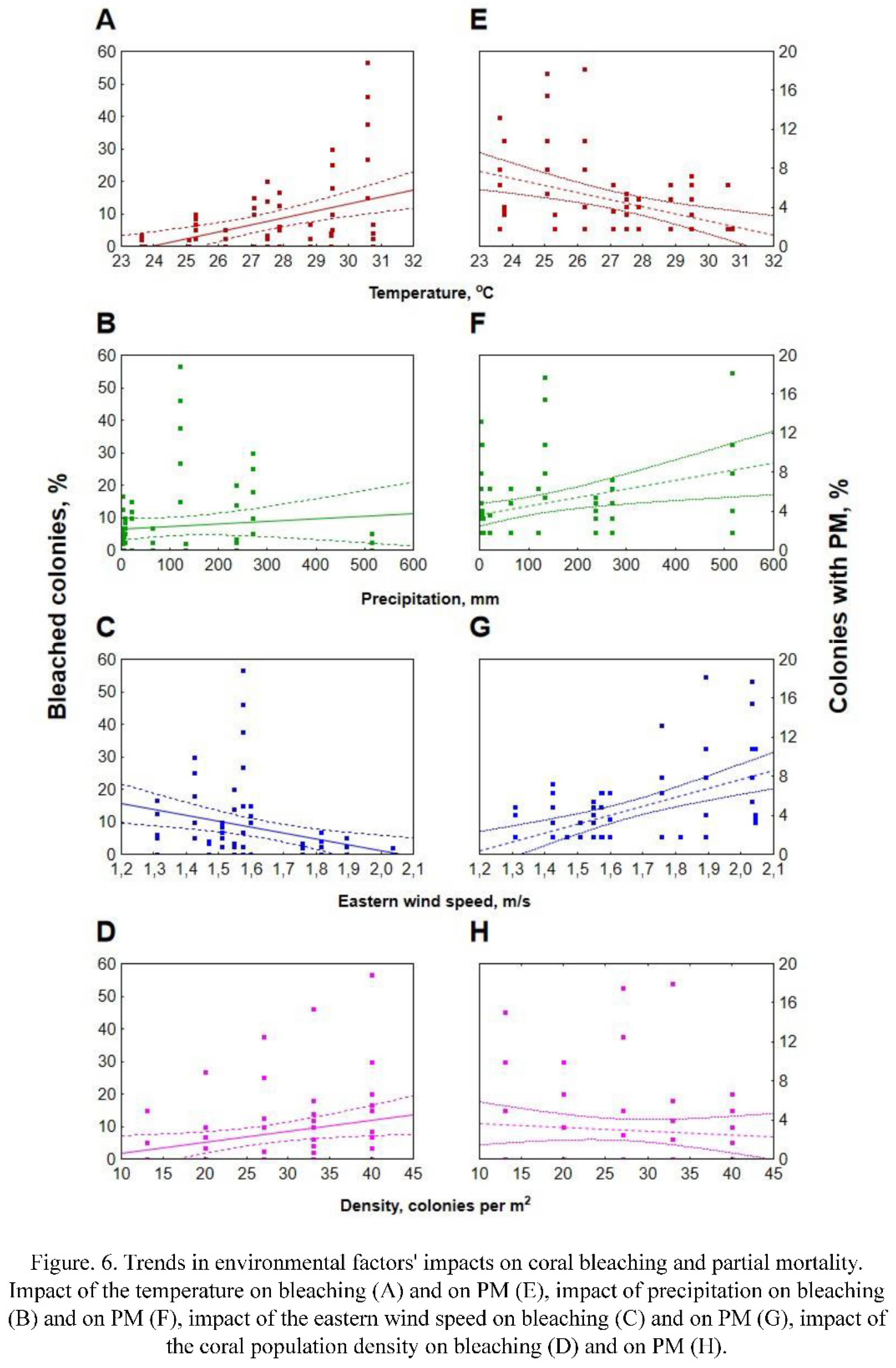

3.5. Impact of environmental factors on bleaching and partial mortality

3.6. Impact of bleaching and partial mortality on mortality

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of environmental factors on bleaching

4.2. Impact of environmental factors on partial mortality

4.3. Colony mortality and its causes

5. Summary

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

References

- Naumov D.V., Propp M.V., Rybakov S.H. 1985. World of corals. Leningrad Gidrometizdat. [in Russian].

- Afrin Z. (2021). Determining Thermal stress using indices: sea surface temperature anomalies, degree heating days and heating rate to allow for-casting of coral bleaching risk. School of Marine Science, University of the South Pacific.

- Anthony K. R. N., Larcombe P. (2000). Coral reefs in turbid waters: sediment-induced stresses in corals and likely mechanisms of adaptation. Proceedings 9th International Coral Reef Symposium, Bali, Indonesia.

- Banaszak A.T., Lesser M.P. (2009). Effects of solar ultraviolet radiation on coral reef organisms. Photochem Photobiol Sci 8. [CrossRef]

- Banner A. (1968). A fresh-water “kill” on the coral reefs of Hawaii. Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawaii.

- Berkelmans R., Willis B.L. (1999). Seasonal and local spatial patterns in the upper thermal limits of corals on the inshore Central Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs. 18. [CrossRef]

- Bellwood D.R., Hoey A.S., Choat J.H. (2003). Limited functional redundancy in high diversity systems: resilience and ecosystem function on coral reefs. Ecology Letters. 6:4. [CrossRef]

- Birrell C.L., McCook L.J, Willis B.L. (2005). Effects of algal turfs and sediment on coral settlement. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 51:1–4. [CrossRef]

- Britayev T.A., Petrochenko R.A., Burmistrova Yu.A., Nguyen T.H., Lishchenko F.V. (2023). Density and bleaching of corals and their relationship to the coral symbiotic community. Diversity.15:3. [CrossRef]

- Brown B.E. Coral bleaching: causes and consequences. (1997). Coral Reefs. 16. [CrossRef]

- Brown B.E., Dunne R.P., Ambarsari I., Le Tissier M., Satapoomin U. (1999). Seasonal fluctuations in environmental factors and variations in symbiotic algae and chlorophyll pigments in four Indo-Pacific coral species. MEPS. 191. [CrossRef]

- Brown C.J., Saunders M.I., Possingham H.P., Richardson A.J. (2013). Managing for Interactions between local and global stressors of ecosystems. PLoS ONE. 8:6. [CrossRef]

- Carilli J., Donner S.D., Hartmann A.C. (2012). Historical temperature variability affects coral response to heat stress. PLoS ONE. 7:3. [CrossRef]

- Coles, S.L., Jokiel, P.L. (1978). Synergistic effects of temperature, salinity and light on the hermatypic coral Montipora verrucosa. Marine Biology. 49. doi:10.1007/BF00391130.

- Combillet, L., Fabregat-Malé, S., Mena, S., Marı́n-Moraga, J. A., Gutierrez, M., and Alvarado, J. J. (2022). Pocillopora spp. growth analysis on restoration structures in an Eastern Tropical Pacific upwelling area. PeerJ 10: e13248. [CrossRef]

- Cornwall C.E., Comeau S., Kornder N.A., Perry C.T., Hooidonk R., DeCarlo T.M., Pratchett M.S., Anderson K.D., Browne N., Carpenter R., Diaz-Pulido G., D'Olivo J.P., Doo S.S., Figueiredo J., Fortunato S.A.V., Kennedy E., Lantz C.A., McCulloch M.T., González-Rivero M., Schoepf V., Smithers S.G., Lowe R.J. (2021). Global declines in coral reef calcium carbonate production under ocean acidification and warming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118:21. [CrossRef]

- Crain C.M., Kroeker K., Halpern B.S. Interactive and cumulative effects of multiple human stressors in marine systems. (2008). Ecology Letters. 11. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01253.x.

- Dautova T.N., Latypov Y.Y., Savinkin O.V. (2007). “Annotated checklist of scleractinian corals, millepores and Heliopora of Nhatrang Bay” in Bentic fauna of the Bay of Nhatrang Southern Vietnam, eds. T.A. Britayev and D.S. Pavlov (KMK Scientific Press), 13-61.

- Diaz-Pulido G., Harii S., McCook L.J., Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2010). The impact of benthic algae on the settlement of a reef-building coral. Coral Reefs. 29. [CrossRef]

- Douglas A.E. Coral bleaching – how and why? (2003). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 46. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00037-7.

- Eakin C.M., Lough J.M., Heron S.F. (2009). “Climate Variability and Change: Monitoring Data and Evidence for Increased Coral Bleaching Stress” In Coral Bleaching: Patterns, Processes, Causes and Consequences, eds. M. J. H. Oppen and J. M. Lough (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg), 41-67.

- Eddy T.D., Lam V.W.Y, Reygondeau G., Cisneros-Montemayor A.M., Greer K., Palomares M., Bruno J.F., Ota Y., Cheung W. (2021). Global decline in capacity of coral reefs to provide ecosystem services. 4:9. [CrossRef]

- Fabricius K. (2011). “Factors determining the resilience of coral reefs to eutrophication: a review and conceptual model” in Coral Reefs: An Ecosystem in Transition, eds. Z. Dubinsky and N. Stambler (Springer), 493-505.

- Ferrario F., Beck M.W., Storlazzi C.D., Micheli F., Shepard C.C., Airoldi L. (2014). The effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation. Nature Communications. 13:5:3794. [CrossRef]

- Ferse S.C.A. (2010). Poor Performance of Corals Transplanted onto Substrates of Short Durability. Restoration Ecology. 18:4. [CrossRef]

- Fine M., Tchernov D. (2007). Scleractinian coral species survive and recover from decalcification. Science. 315:5820. [CrossRef]

- Fisher R., Bessell-Browne P., Jones R. (2019). Synergistic and antagonistic impacts of suspended sediments and thermal stress on corals. Nature Communications. 10:1. [CrossRef]

- Fitt W.K., McFarland F.K., Warner M.E., Chilcoat G.C. (2000). Seasonal patterns of tissue biomass and densities of symbiotic dinoflagellates in reef corals and relation to coral bleaching. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:3. [CrossRef]

- Fitt W.K., Brown B.E., Warner M.E., Dunne R.P. (2001). Coral bleaching: Interpretation of thermal tolerance limits and thermal thresholds in tropical corals. Coral Reefs. 20:1. [CrossRef]

- Fong J., Tang P.P.Y., Deignan L.K., Seah J.C.L., McDougald D., Rice S.A., Todd P.A. Chemically Mediated Interactions with Macroalgae Negatively Affect Coral Health but Induce Limited Changes in Coral Microbiomes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2261. [CrossRef]

- Glynn P.W. Effects of the 1997-98 El Niño-Southern Oscillation on Eastern Pacific corals and coral reefs: An overview. (2000). Proceedings 9th International Coral Reef Symposium, Bali, Indonesia. 2, 23-27.

- Guillemot N., Chabanet P., Le Pape O. Cyclone effects on coral reef habitats in New Caledonia (South Pacific). (2010). Coral Reefs. 29. [CrossRef]

- Harmelin-Vivien L.M. The Effects of Storms and Cyclones on Coral Reefs: A Review. (1994). Journal of Coastal Research. 12, 211-231.

- Hennige S., Larsson A., Orejas C., Gori A., De Clippele L., Lee Y., Jimeno G., Georgoulas K., Kamenos N., Roberts J. (2021). Using the Goldilocks Principle to model coral ecosystem engineering. Proc Biol Sci. 288:1956. [CrossRef]

- Heron S., Morgan J., Eakin M., Skirving W. (2008). “Hurricanes and their effects on coral reefs” in Status of Caribbean Coral Reefs after Bleaching and Hurricanes in 2005. eds. C. Wilkinson, D. Souter (Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, and Reef and Rainforest Research Centre), 31-36.

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. (1999). Climate Change, Coral Bleaching and the Future of the World’s Coral Reefs. Marine and Freshwater Research. 50. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2011). Coral reef ecosystems and anthropogenic climate change. Regional Environmental Change. 11. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2014). Coral reefs in the Anthropocene: persistence or the end of the line? Geol. Soc. Spec. 395:1. [CrossRef]

- Hughes T.P., Barnes M.L., Bellwood D.R., Cinner J.E., Cumming G.S., Jeremy B., Jackson J., Kleypas J., Leemput I.A., Lough J.M., Morrison T.H., Palumbi S.R., Nes E.H., Scheffer M. (2017). Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature. 546(7656):82-90. [CrossRef]

- Jokiel P., Hunter C., Taguchi S., Watarai L. (1993). Ecological impact of a fresh-water "reef kill" in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii. Coral Reef. 12. doi:10.1007/BF0033447.

- Jokiel P., Brown E.K. (2004). Global warming, regional trends and inshore environmental conditions influence coral bleaching in Hawaii. Global Change Biology. 10. [CrossRef]

- Jokiel P. (2006). Impact of storm waves and storm floods on Hawaiian reefs. Proceedings of the 10th International Coral Reef Symposium, 282-284.

- Jompa J., McCook L. (2003). Contrasting effects of turf algae on corals: massive Porites spp. are unaffected by mixed-species turfs, but killed by the red alga Anotrichium tenue. MEPS. 258. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.C., Forsman, Z.H., Flot, JF., Schmidt-Roach S., Pinzón J.H.C., Knapp I., Toonen R.J. (2017). A genomic glance through the fog of plasticity and diversification in Pocillopora. Sci Rep. 7:5991. [CrossRef]

- Le D.M., Vlasova G.A., Nguyen D.T.T., Pham H.S., Nguyen T.V. (2022). Distribution features of the weather conditions in Nha Trang Bay (The South China Sea). Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 22. [CrossRef]

- Latypov Y.Y. (2016). Results of Thirty Years of Research on Corals and Reefs of Vietnam. Open Journal of Marine Science. 6. [CrossRef]

- Lesser M.P. (2010). Coral Bleaching: Causes and Mechanisms. Coral Reef. [CrossRef]

- Lough J.M., Anderson K.D., Hughes T.P. (2018). Increasing thermal stress for tropical coral reefs: 1871–2017. Sci Rep. 8. [CrossRef]

- Loya Y., Sakai K., Yamazato K., Nakano Y., Sambali H., van Woesik R. (2001). Coral bleaching: the winners and the losers. Ecology Letters. [CrossRef]

- Manzello D., Brandt M., Smith T., Lirman D., Hendee J., Nemeth R. (2007). Hurricanes benefit bleached corals. PNAS. 104:29. [CrossRef]

- Mbije N.E.J., Spanier E., Rinkevichc B. (2010). Testing the first phase of the ‘gardening concept’ as an applicable tool in restoring denuded reefs in Tanzania. Ecological Engineering. 36. [CrossRef]

- McCook L. (2001). Competition between corals and algal turfs along a gradient of terrestrial influence in the nearshore central Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs. 19:4. [CrossRef]

- Meesters E.H., Wesseling I., Bak R.P.M (1996). Partial Mortality in Three Species of Reef-Building Corals and the Relation with Colony Morphology. Bulletin of Marine Science. 58, 838-852.

- Montano S., Seveso D., Galli P., Obura D. (2010). Assessing coral bleaching and recovery with a colour reference card in Watamu Marine Park, Kenya. Hydrobiologia. 655:1. [CrossRef]

- Muller E.M., Sartor C., Alcaraz N., van Woesik R. (2020). Spatial Epidemiology of the Stony-Coral-Tissue-Loss Disease in Florida. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T., van Woesik R. (2001). Water-flow rates and passive diffusion partially explain differential survival of corals during the 1998 bleaching event. MEPS. 212. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T., Yamasaki H., van Woesik R. (2003). Water flow facilitates recovery from bleaching in the coral Stylophora pistillata. MEPS. 256. [CrossRef]

- Nir O., Gruber D.F., Shemesh E., Glasser E., Tchernov D. (2014). Seasonal Mesophotic Coral Bleaching of Stylophora pistillata in the Northern Red Sea. PLoS ONE. 9:1. [CrossRef]

- Nugues M.M., Roberts C.M. (2003). Partial mortality in massive reef corals as an indicator of sediment stress on coral reefs. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 46:3. [CrossRef]

- Oury N., Noël C., Mona S., Aurelle D., Magalon H. (2023). From genomics to integrative species delimitation? The case study of the Indo-Pacific Pocillopora corals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 184:107803. [CrossRef]

- Pandolfi J.M., Bradbury R.H., Sala E., Hughes T.P., Bjorndal K.A., Cooke R.G., McArdle D., McClenachan L., Newman M.G.H., Paredes G., Warner R., Jackson J.B.C. (2003). Global Trajectories of the Long-Term Decline of Coral Reef Ecosystems. Science. 301:5635. [CrossRef]

- Piniak G., Storlazzi C. (2008). Diurnal variability in turbidity and coral fluorescence on a fringing reef flat: Southern Molokai, Hawaii. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science.77:1. [CrossRef]

- Pisapia C., Pratchett M.S. (2014) Spatial Variation in Background Mortality among Dominant Coral Taxa on Australia's Great Barrier Reef. PLoS ONE. 9:6. [CrossRef]

- Philipp E., Fabricius K. (2003). Photophysiological stress in scleractinian corals in response to short-term sedimentation. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 287:1. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z., Yu K., Wang Y., Xu L., Huang X., Chen B., Li Y., Wang W., Pan Z. (2019). Spatial and Intergeneric Variation in Physiological Indicators of Corals in the South China Sea: Insights Into Their Current State and Their Adaptability to Environmental Stress. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. [CrossRef]

- Reaka-Kudla M., Wilson D., Wilson E. (1997). The Global Biodiversity of Coral Reefs: A Comparison with Rain Forests. Joseph Henry Press. 83-108.

- Rasher D.B., Stout E.P., Engel S., Kubanek J., Hay M.E. Macroalgal terpenes function as allelopathic agents against reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17725–17731.

- Rivas N., Gómez C.E., Millán S., Mejía-Quintero K., Chasqui L. (2023). Coral reef degradation at an atoll of the Western Colombian Caribbean. PeerJ. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Villalobos J.C., Work T.M., Calderon-Aguilera L.E., Reyes-Bonilla H., Hernández L. (2015). Explained and unexplained tissue loss in corals from the Tropical Eastern Pacific. DAO. 116. [CrossRef]

- Silbiger N.J., Nelson C.E., Remple K., Sevilla J.K., Quinlan Z.A., Putnam H.M., Fox M.D., Donahue M.J. (2018). Nutrient pollution disrupts key ecosystem functions on coral reefs. Proceedings of the Royal Society. [CrossRef]

- Siebeck U.E., Marshall N.J., Klüter A., Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2006). Monitoring coral bleaching using a colour reference card. Coral Reefs. 25:3. [CrossRef]

- Shu L., Ke-fu Yu., Shi Qi., Chen T. (2008). Interspecies and spatial diversity in the symbiotic Zooxanthellae density in corals from northern South China Sea and its relationship to coral reef bleaching. Chinese Science Bulletin. 53:2. [CrossRef]

- Shu L., Ke-fu Yu., Chen T., Shi Qi. (2011). Assessment of coral bleaching using symbiotic zooxanthellae density and satellite remote sensing data in the Nansha Islands, South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin. 56:10. [CrossRef]

- Smith J.E., Shaw M., Edwards R., Obura D., Pantos O., Sala E., Sandin S., Smriga S., Hatay M., Rohwer F. (2006). Indirect effects of algae on coral: algae-mediated, microbe-induced coral mortality. Ecology letters. Ecol Lett. 9:7. [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko K.S. Degradation of Coral Reefs under Complex Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Factors with Nha Trang Bay (Vietnam) as an Example. (2023). Biology Bulletin Reviews. 13: 5. [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko K.S., Britayev T.A., Huan N.H., Pereladov M.V., Latypov Y.Y. (2016). Influence of anthropogenic pressure and seasonal upwelling on coral reefs in Nha Trang Bay (Central Vietnam). Marine Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko K.S., Dung Vu.V., Ha Vo.T., Huan N.H. (2023). Coral reef collapse in South-Central Vietnam: a consequence of multiple negative effects. Aquat. Ecol. 57. [CrossRef]

- Wangpraseurt D., Weber M., Røy H., Polerecky L., de Beer D., Suharsono, Nugues M. (2012). In situ oxygen dynamics in coral-algal interactions. PLoS One. 7:2. [CrossRef]

- Warner M.E., Chilcoat G.C., McFarland F.K., Fitt W.K. (2002). Seasonal fluctuations in the photosynthetic capacity of photosystem II in symbiotic dinoflagellates in the Caribbean reef-building coral Montastraea. Marine Biology. 141. [CrossRef]

- Wenger A.S., Fabricius K., Jones G.P., Brodie J.E. (2015). Effects of sedimentation, eutrophication, and chemical pollution on coral reef fishes. Ecology of Fishes on Coral Reefs. [CrossRef]

- Weiss A., Martindale R. (2017). Crustose coralline algae increased framework and diversity on ancient coral reefs. PLoS ONE. 12:8. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson C. (2004). Status of coral reefs of the world. Australian Institute of Marine Science. 1.

- Zweifler A., O'leary M., Morgan K., Browne N. (2021). Turbid Coral Reefs: Past, Present and Future-A Review. Diversity. 13:6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).