Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

13 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cultural Ecosystem services: are they significant to MSP ?

3. Materials and Methods

- written in a language other than English (n=3),

- not related to CES (n=1),

- theoretical articles - discussions and reviews, etc. (n=18),

- not focused on the coastal zone or on the marine environment (n=15)

3. Results

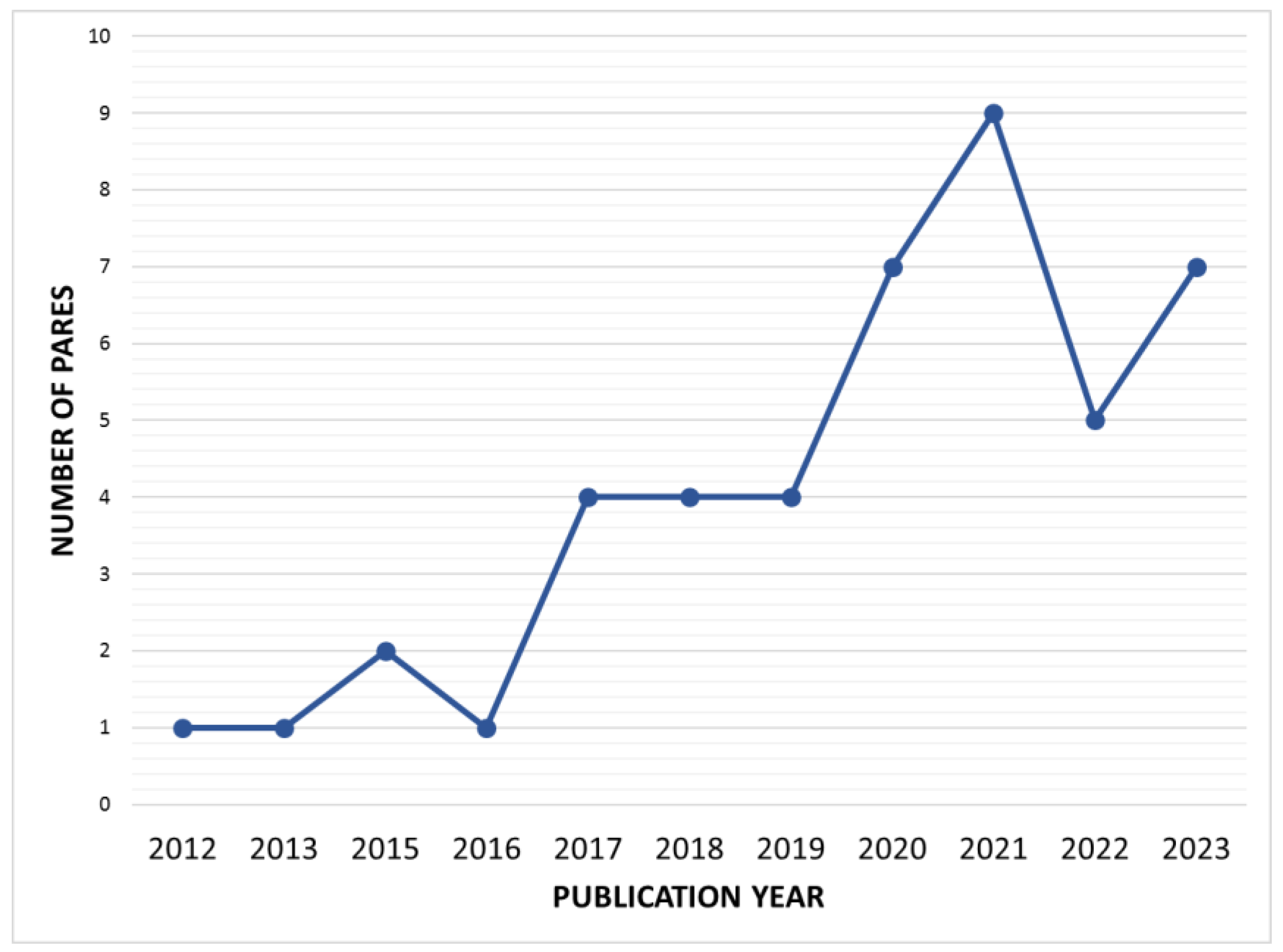

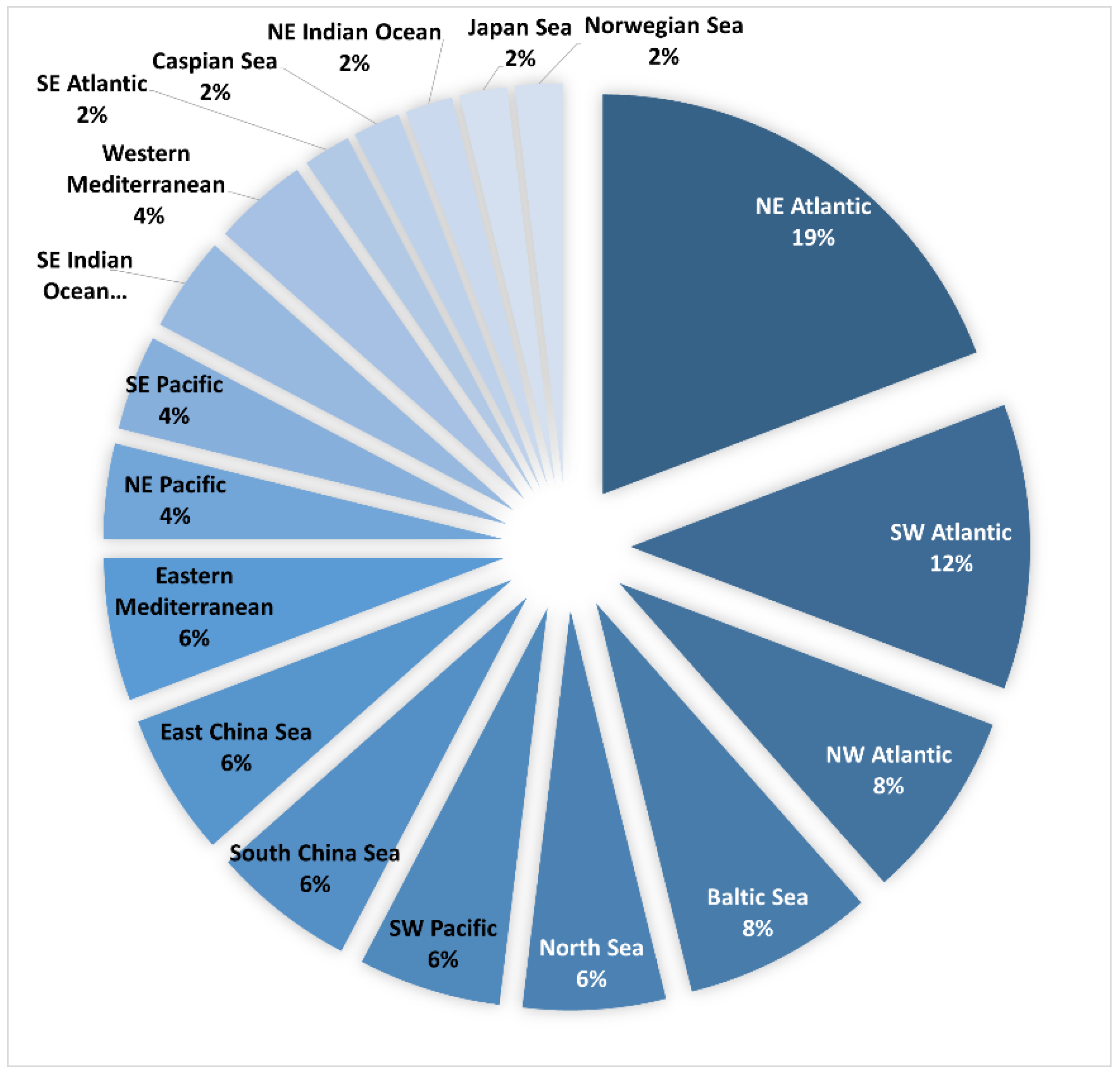

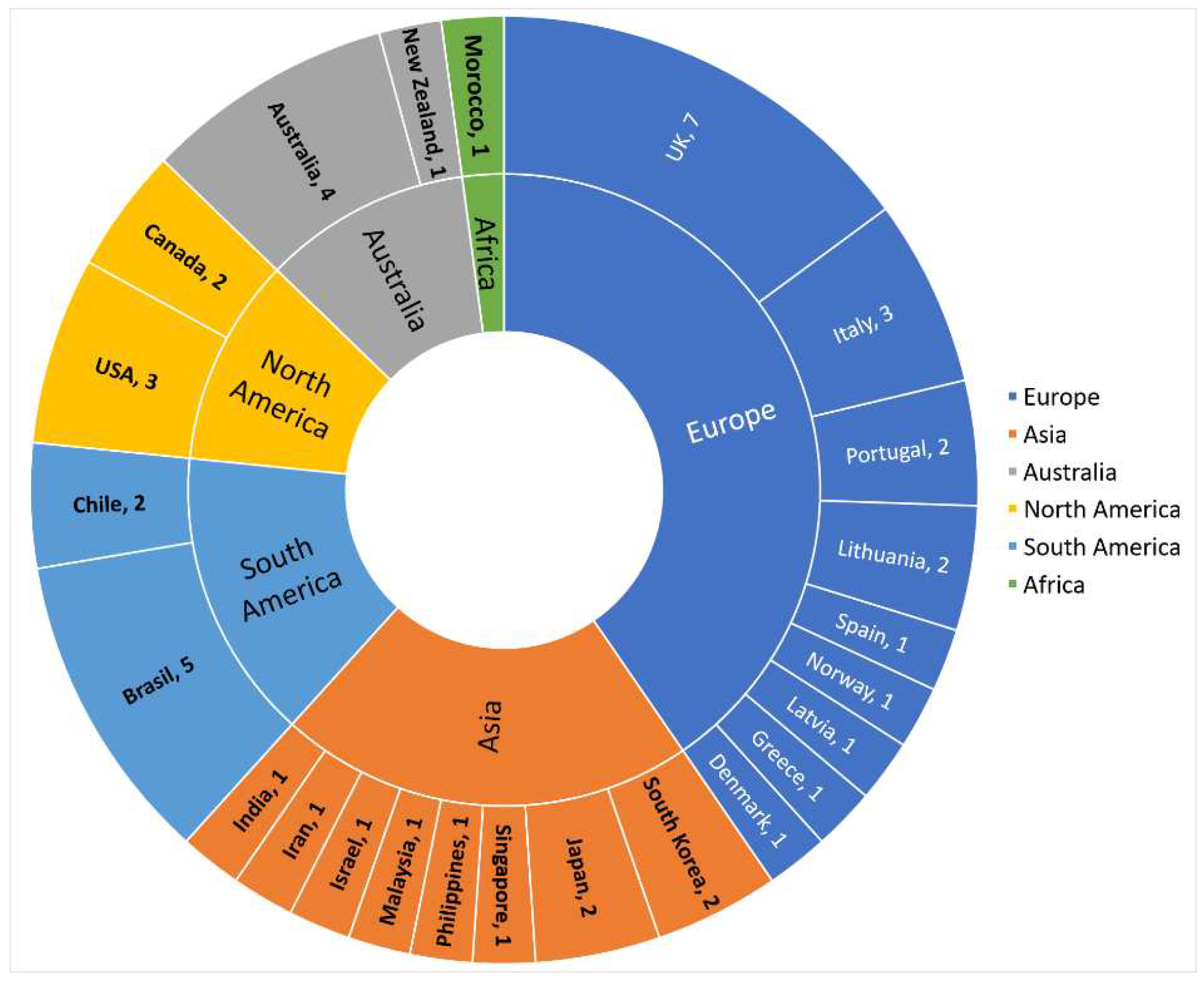

3.1. Spatial and temporal distribution of the papers

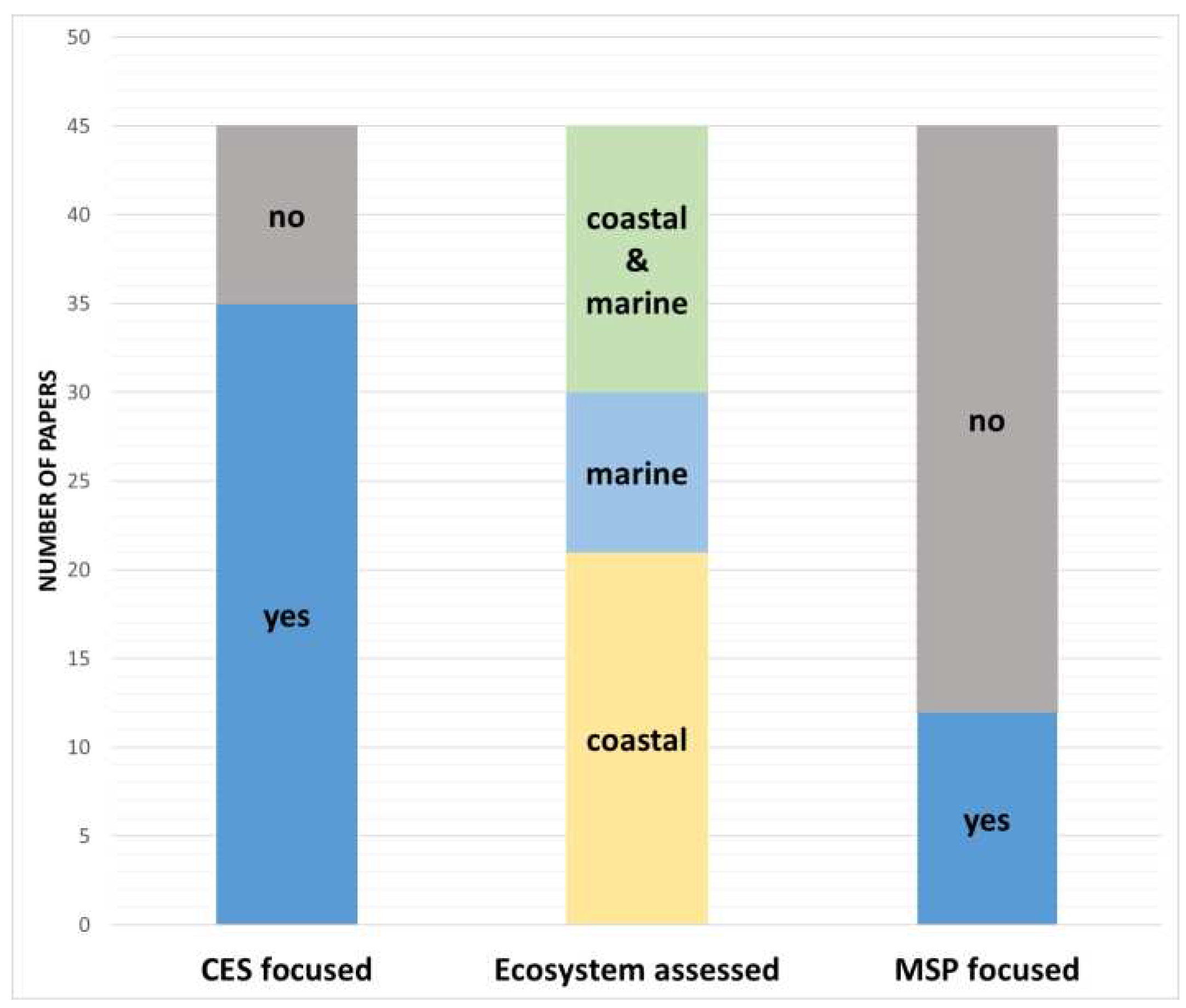

3.2. Focus of the papers

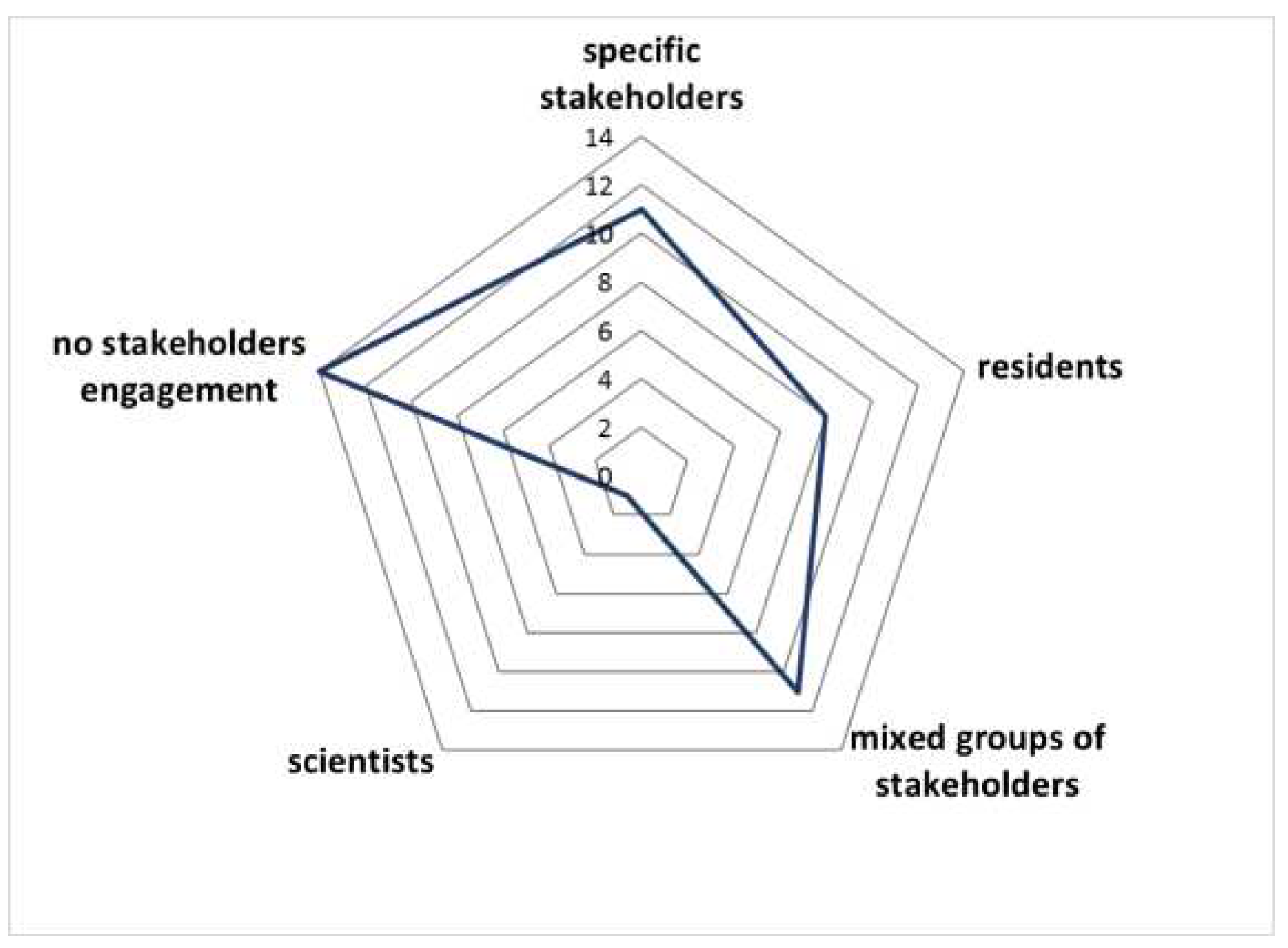

3.3. Type of engaged stakeholders

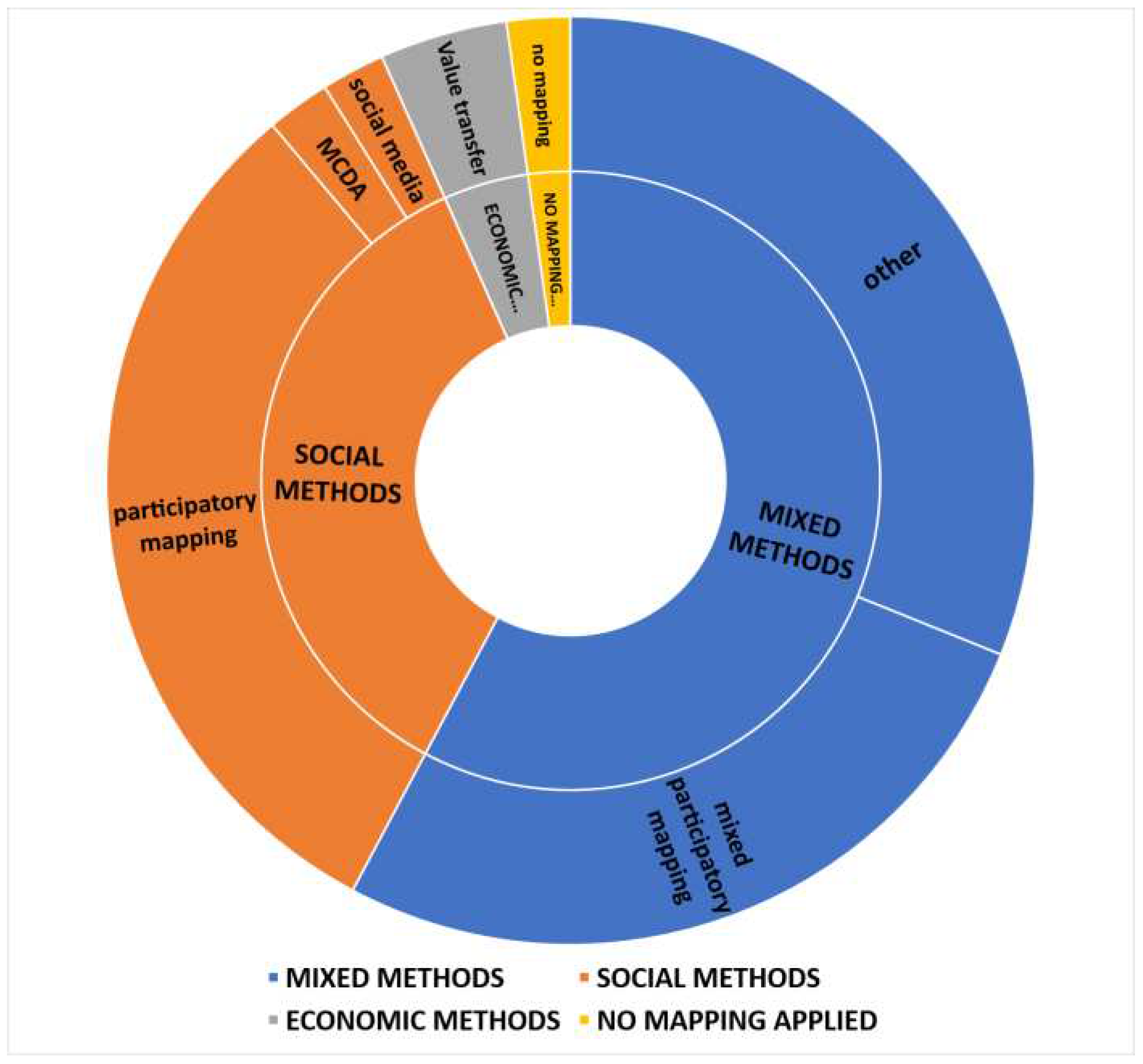

3.4. Mapping approaches

3.4.1. Use of paricipatory GIS

3.4.2. Other types of mapping approaches

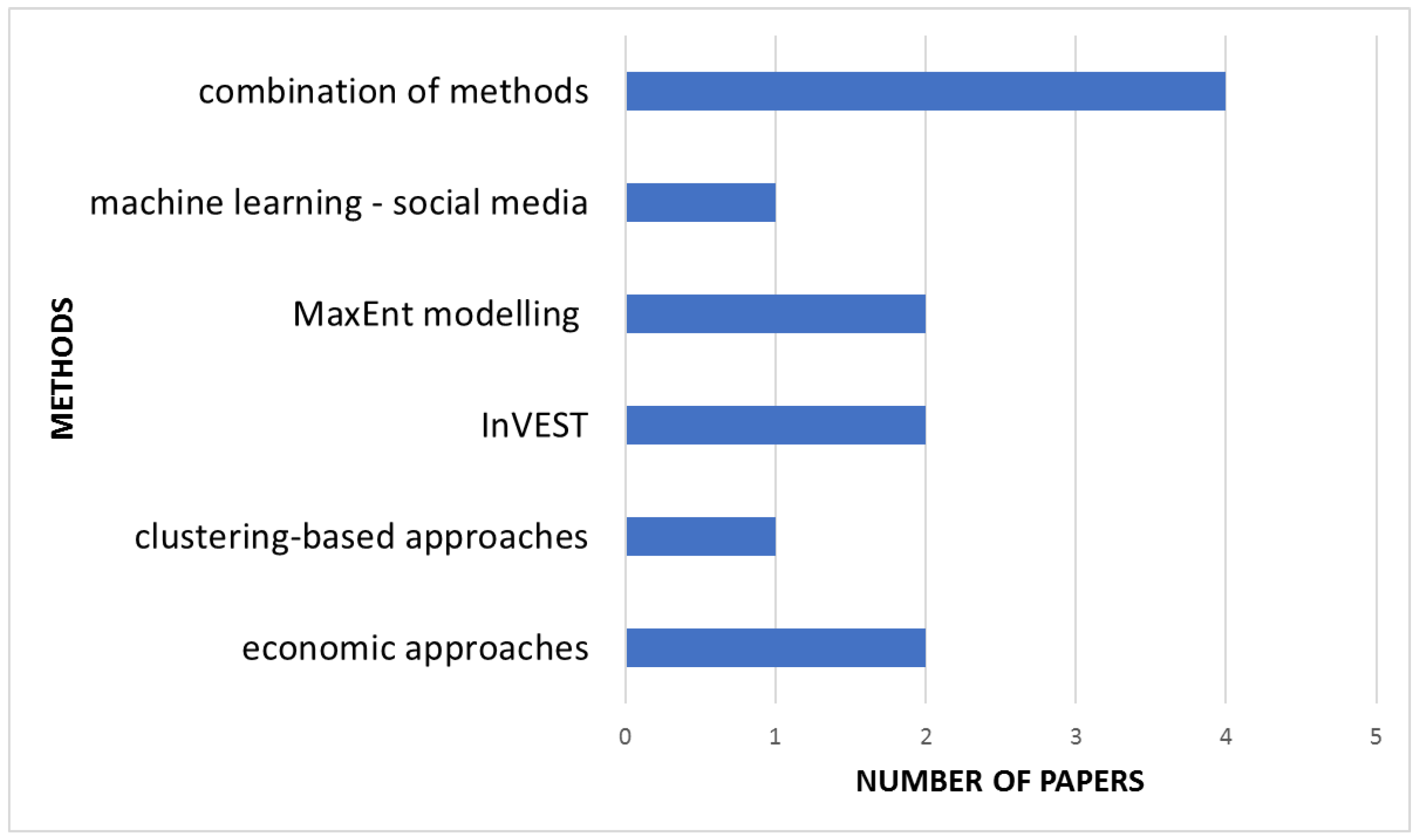

3.5. Valuation Methods Applied

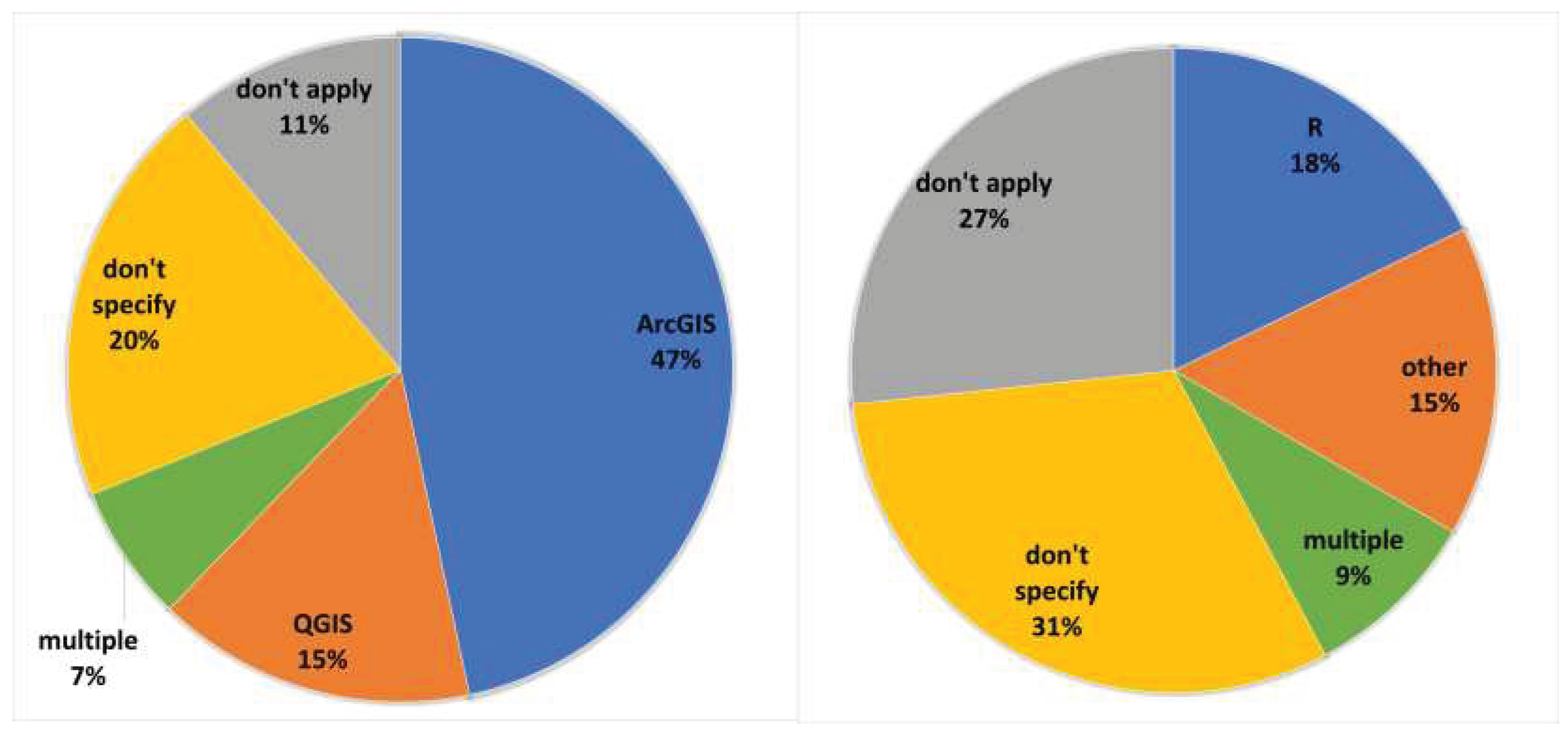

3.6. Techniques, tools and software used

3.6.1. Per category of Desk analysis

- ▪

- Chi-square tests to check if the proportion of photographs ( coming from the social media) and user counts for specific CES, varied significantly between categories or between different sites, in social media analysis [68,81] or to examine the distribution of values in relation to different factors (e.g by coastal and non-coastal areas, by type of marine protected area, by access, by population density) [8,57,73]. In some cases, the chi-square independence analysis test was applied along with proportional analysis, that tests dependence [8,57].

- ▪

- Pearson correlation analysis to verify the accuracy of spatial assessment by comparing the results with existing datasets [56,59,85] or to examine for possible relationships between different coastal activities and the reasons that undermine them [72] or to evaluate spatial association between different CES [68].

- ▪

- The non-parametric Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to examine the correlation between different pairs of values (e.g., non-monetary – monetary, non-monetary-threats) [23] and between different CES and CES components (e.g., naturalness, tree density, silent areas, religious sites, accommodation) [62].

- ▪

- Finally, Canonical Correlation Analysis was used to investigate whether coastal activities (e.g., fishing) were correlated with stressors (e.g., overcrowded spaces) [72].

- Multinomial regression to identify the demographic identity of each group, as well as the environmental drivers that drive the location of CES for each of the groups [71]

- Multivariate linear regression to assess tourists’ preferences for cultural and natural landscapes (e.g., natural features, land-cover and land-use types, accessibility, and amenities for tourists) using multiple sources of UGC [85]

- k-means cluster analysis of the Flickr users to better contextualize the types and association of CES engagement at the user level [68].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to compare the results of different methods [80].

- ▪

- ▪

- macro-ecological modelling (MaxEnt) to model spatial distribution of different CES in social-media analysis [81];

- ▪

3.6.2. Participatory techniques tools and software

4. Discussion

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- ▪

- mapping different aspects of ES (supply, demand, flow) [62]

- ▪

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type of Desk analysis | Methods, Techniques, Models, Tools | Software and tools used |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Analysis (GIS) | Basic techniques and tools (kernel density tool, point density tool, line density tool; zonal statistics; buffer technique; intersect; spatial join; map algebra; ′′XY to Line ” tool; extract multivalues to points tool; bootstrap sampling technique; minimum Euclidean distance; cost distance; Calculate Distance Band from Neighbor Count), viewshed analysis, classification methods (supervised maximum likelihood method), interpolation methods [Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW), Kriging method], spatial autocorrelation [semivariograms, Global Moran’s I tool, Incremental Spatial Autocorrelation tool], cluster analysis [Cluster and Outlier Analysis (Anselin Local Moran’s I), Getis–Ord (Gi*], Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) (1), radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction of images (2), NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) (2) | ArcGIS, QGIS, Python (1) (Python spatial analysis library – PySAL), ENVI (2) |

| Statistical Analysis | chi-square test; proportional analysis; Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn test; Steel–Dwass test; one-way ANOVA; Analysis of similarities – ANOSIM(1), analysis of similarity percentages (SIMPER)(1); Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA)(1), multinomial regression, multivariate linear regression, Pearson’s correlation, Spearman correlation analysis, Canonical Correlation Analysis, hierarchical cluster analysis – elbow method, k-means cluster analysis, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Correspondence analysis (CA), Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) – multiple group method, mixed logit models (2) Fleiss’ kappa; minimum/maximum method normalization method; Shapiro–Wilk test; t-test; z-test; Wald test; Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test; multicollinearity tests; Bigram Language Model; meta-regression functions; multiple hedonic pricing OLS regressions | Microsoft Excel, R, SPSS, Statistica, SAS studio, JMP Pro, PRIMER(1), NLOGIT(2) |

| Modelling for Ecosystem Services | overlap analysis model, recreation model, Habitat Risk Assessment (HRA) model, habitat quality model, coastal vulnerability model, coastal protection; carbon storage and sequestration, crop production | InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs), SoLVES (Social Values for Ecosystem Services) |

| Other | machine learning to automatically assign (1),(2), macro-ecological modelling (3), location-based pressure model(4), future dynamic land change model (5), Sea level rise inundation pressure – spatial model from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administra tion’s (NOAA), image processing (6), MaxN routine (7) | Cloud computing platform Clarifai (1), Google Cloud Vision API (2), MaxEnt (3), python – Tools4MSP (4), FUTure Urban-Regional Environment Simulation (FUTURES)(5), photoQuad software (6), EventMeasure (SeaGIS) software (7) |

| Title, Acronym, duration and Lead partner of the project | Focus | Innovation Acheivement |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HERitage in CULtural landscapES HERCULES, 2013-2016 Humboldt University in Berlin |

Focused on preserving cultural landscapes through the empowerment of public and private actors.(such as, PPGIS and crowdsourcing technologies) for the assessment of cultural landscapes in different spatial scales (local, national, pan-European), as well as in eight cases studies of different countries (Estonia, Greece, Switzerland, France, Spain, UK, Netherlands, and Sweden. | Use of innovating technologies and tools. Through the Knowledge Hub platform communication amongst stakeholders and the general public was achieved. | [103,104]. Claudia, B. et al. D3.1 List and Documentation of Case Study Landscapes Selected for HERCULES. WP3 Landscape-Scale Case Studies (Short-Term History).; 2014; Trommler, K.; Plieninger, T. Sustainable Futures for Europe’s Heritage in Cultural Landscapes: Tools for Understanding, Managing, and Protecting Landscape Functions and Values.; MID-TERM ASSESSMENT REPORT; HERCULES, FP7, Collaborative Project: Berlin / Copenhagen, 2015; |

|

LIFE-IP 4 Natura Project Integrated actions for the conservation and management of Natura 2000 sites, species, habitats and ecosystems, 2018-2025 |

Provided a web-based PPGIS, developed by Greek academia, government and NGOs. | PPGIS/webGIS which presents ES provided by Greek ecosystems (such as timber production, climate regulation, tourism and recreation) and is available for governmental, professional and public use. | [105]. Mallinis, G.; Chalkidou, S.; Roustanis, T.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Chrysafis, I.; Karolos, I.-A.; Vagiona, D.; Kavvadia, A.; Dimopoulos, P.; Mitsopoulos, I. A National Scale Web Mapping Platform for Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services in Greece. Ecological Informatics 2023, 78, 102349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102349. |

|

Mare Nostrum funded by the EC under the ENPI CBCMED Programme |

A cross-border project exploring new ways of protecting the Mediterranean coastline | A web-based PPGIS was developed in order to collect local knowledge and draw eco-heritage trails in the Grand Harbour of Malta | [106] Pellach, C.; Carmon, D.; Teschner, N.; Boral, R. Legal-Institutional Instruments for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in the Mediterranean. Final Report, 2016, MARE NOSTRUM PROJECT; Https://Curs.Net.Technion.Ac.Il/Files/2018/11/Mare-Nostrum-Final-Report.Pdf. |

|

Horizon 2020 REINVENT Re-inventory-ing Heritage: Exploring the potential of PPGIS to capture heritage values and dissonance, 2016-2018 (Under a Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement for the research of the public participation in cultural heritage management ) |

Addressed challenges related to the management of cultural heritage in Europe in a cross-border context, using as case study the city of Derry~Londonderry, in North West Ireland. | Through MyValuedPlaces (a web-based pilot survey) communities’ values are captured (such as, recreation, spiritual, therapeutic) at multiple scales. The project developed “the first cross-border cultural heritage Atlas” | [107,108]. McClelland, A. Spaces for Public Participation: valuing the cross-border landscape in North West Ireland’. Irish Geography 2019, 52(2), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.2014/igj.v52i2.1401. McClelland, A. Towards a Cross-Border Cultural Heritage Atlas for the North West: Data Availability, Webhosting and Guiding Principles for the GIS Mapping of Heritage Inventory and Other Datasets.; 1; National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis (NIRSA), Maynooth University Social Science Institute (MUSSI), 2016; |

|

PERICLES project Preserving and sustainably governing cultural heritage and landscapes in European coastal and maritime regions, 2018-2021 Funded by Horizon 2020. |

PERICLES promoted sustainable, participatory governance of maritime cultural heritage in European coastal and maritime regions through an interdisciplinary and geo-graphically wide-ranging approach. | The project developed an online mapping platform called “MapYourHeritage” for the collection of data on tangible and intangible cultural heritage on eight European regions (e.g., Aegean Sea, Brittany, Denmark). The aim of the portal was to provide an opportunity for the public to engage with coastal and marine cultural heritage. | [100]. Kenter, J.; Cambridge, H. Interactive Online CH Mapping Portal. PrEseRvIng and Sustainably Governing Cultural Heritage and Landscapes in European Coastal and Maritime regionS, PERICLES_D3.1_v2.0 Dissemination Level: PU, 2019.; |

| PPGIS/ WebGIS platforms |

Project Acromym |

General Framework | Participatory mapping - CES mapped. | ES focused Participatory mapping | Focus on Coastal or Marine enviroment | ICZM/ MSP | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Hub | HERCULES | cultural landscape – ecosystem services | outdoor activities, social interactions, aesthetic values, beautiful landscape or landmark, inspirational, spiritual or religious place, feeling or value, appreciation of a specific place as such, independently of any benefit to humans | yes | no | no | CORDIS database |

| ppGIS/webGIS LIFE-IP 4 NATURA | LIFE-IP 4 NATURA | Ecosystem Services | cultural heritage, enviromental education and research, recreation and tourism in nature, aesthetics, spiritual and religious importance | yes | no | no | |

| Grand Harbour Charter |

Mare Nostrum project | cultural & ecological values | eco-heritage trails | no | yes | yes | |

| MapYourHeritage | PERICLES | maritime cultural heritage |

cultural, industrial and natural heritage | no | yes | yes | CORDIS database |

| REINVENT Project Mapping Viewer | REINVENT | cultural heritage - landscape values |

aesthetic, economic, recreational, therapeutic, social, biological diversity, life sustaining, spiritual, intrinsic, wilderness, social, heritage | yes | no | no | CORDIS database |

References

- Cabral, H.; Fonseca, V.; Sousa, T.; Costa Leal, M. Synergistic Effects of Climate Change and Marine Pollution: An Overlooked Interaction in Coastal and Estuarine Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattam, C.; Atkins, J.P.; Beaumont, N.; Bӧrger, T.; Böhnke-Henrichs, A.; Burdon, D.; De Groot, R.; Hoefnagel, E.; Nunes, P.A.L.D.; Piwowarczyk, J.; et al. Marine ecosystem services: Linking indicators to their classification. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 49, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.P.; Alves, F.L. A model to integrate ecosystem services into spatial planning: Ria de Aveiro coastal lagoon study. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 195, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, M.; Magnussen, K.; Heiskanen, A.-S.; Navrud, S.; Viitasalo, M. Ecosystem services in MSP, Ecosystem services approach as a common Nordic understanding for MSP; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen K, Denmark, 2017; p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- Pennino, M.G.; Brodie, S.; Frainer, A.; Lopes, P.F.M.; Lopez, J.; Ortega-Cisneros, K.; Selim, S.; Vaidianu, N. The Missing Layers: Integrating Sociocultural Values Into Marine Spatial Planning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 633198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M.; Kyvelou, S. Aspects of marine spatial planning and governance: adapting to the transboundary nature and the special conditions of the sea. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 8, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskule, A.; Klepers, A.; Veidemane, K. Mapping and assessment of cultural ecosystem services of Latvian coastal areas. One Ecosyst. 2018, 3, e25499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobryn, H.T.; Brown, G.; Munro, J.; Moore, S.A. Cultural ecosystem values of the Kimberley coastline: An empirical analysis with implications for coastal and marine policy. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 162, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Vergara, X.; Kusch, A.; Campos, G.; Droguett, D. Mapping ecosystem services for marine spatial planning: Recreation opportunities in Sub-Antarctic Chile. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frau, A.; Hinz, H.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Kaiser, M.J. Spatially explicit economic assessment of cultural ecosystem services: Non-extractive recreational uses of the coastal environment related to marine biodiversity. Mar. Policy 2013, 38, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerry, A.D.; Ruckelshaus, M.H.; Arkema, K.K.; Bernhardt, J.R.; Guannel, G.; Kim, C.K.; Marsik, M.; et al. Modeling Benefits from Nature: Using Ecosystem Services to Inform Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. 2012, 8, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakou, E.G.; Kermagoret, C.; Liquete, C.; Ruiz-Frau, A.; Burkhard, K.; Lillebø, A.I.; van Oudenhoven, A.P.E.; Ballé-Béganton, J.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Nieminen, E.; et al. Marine and coastal ecosystem services on the science–policy–practice nexus: challenges and opportunities from 11 European case studies. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European MSP Platform. Available online: www.msp-platform.eu (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Satz, D.; Gould, R.K.; Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.; Norton, B.; Satterfield, T.; Halpern, B.S.; Levine, J.; Woodside, U.; Hannahs, N.; et al. The Challenges of Incorporating Cultural Ecosystem Services into Environmental Assessment. Ambio 2013, 42, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Willis, C.; Winter, M.; Tratalos, J.A.; Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Making space for cultural ecosystem services: Insights from a study of the UK nature improvement initiative. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Braat, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Biodiversity Strategy 2020. EUR-lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/biodiversity-strategy-for-2020.html (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Schaich, H.; Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T. Linking Ecosystem Services with Cultural Landscape Research. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2010, 19, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, S.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.; Halpern, B.S.; et al. Where are Cultural and Social in Ecosystem Services? A Framework for Constructive Engagement. BioScience 2012, 62, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An empirical review of cultural ecosystem service indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.M.A. Navigating coastal values: Participatory mapping of ecosystem services for spatial planning. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 82, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Fagerholm, N. Empirical PPGIS/PGIS mapping of ecosystem services: A review and evaluation. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 13, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O. Integrating Deliberative Monetary Valuation, Systems Modelling and Participatory Mapping to Assess Shared Values of Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Brady, E.; Steen, H.; Bryce, R. Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: Recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem ‘services’. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, G.; D’anna, L.; MacDonald, P. Measuring what we value: The utility of mixed methods approaches for incorporating values into marine social-ecological system management. Mar. Policy 2016, 73, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. Assessing nature's contributions to people. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braat, L.C. Five reasons why the Science publication “Assessing nature’s contributions to people” (Diaz et al. 2018) would not have been accepted in Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 30, A1–A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, K.; Kannen, A.; Adlam, R.; Brooks, C.; Chapman, M.; Cormier, R.; Fischer, C.; Fletcher, S.; Gubbins, M.; Shucksmith, R.; et al. Identifying culturally significant areas for marine spatial planning. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2017, 136, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B.S.; Diamond, J.; Gaines, S.; Gelcich, S.; Gleason, M.; Jennings, S.; Lester, S.; Mace, A.; McCook, L.; McLeod, K.; et al. Near-term priorities for the science, policy and practice of Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning (CMSP). Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Baulcomb, C.; Hall, C.; Hussain, S. Revealing Marine Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Black Sea. Mar. Policy 2014, 50, 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, T.; Burdon, D.; Jackson, E.; Atkins, J.; Saunders, J.; Hastings, E.; Langmead, O. Do marine protected areas deliver flows of ecosystem services to support human welfare? Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.K.; Schaafsma, M. Coastal Zones Ecosystem Services. Valuat. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 9, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisetti, T.; Turner, R.; Jickells, T.; Andrews, J.; Elliott, M.; Schaafsma, M.; Beaumont, N.; Malcolm, S.; Burdon, D.; Adams, C.; et al. Coastal Zone Ecosystem Services: From science to values and decision making—a case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranger, S.; Kenter, J.; Bryce, R.; Cumming, G.; Dapling, T.; Lawes, E.; Richardson, P. Forming shared values in conservation management: An interpretive-deliberative-democratic approach to including community voices. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulcomb, C.; Fletcher, R.; Lewis, A.; Akoglu, E.; Robinson, L.; von Almen, A.; Hussain, S.; Glenk, K. A pathway to identifying and valuing cultural ecosystem services: An application to marine food webs. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 11, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.I.M.; Alagappar, P.N.; Then, A.Y.-H.; Justine, E.V.; Lim, V.-C.; Goh, H.C. Perspectives of youths on cultural ecosystem services provided by Tun Mustapha Park, Malaysia through a participatory approach. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O.; Bryce, R.; Christie, M.; Cooper, N.; Hockley, N.; Irvine, K.N.; Fazey, I.; O’brien, L.; Orchard-Webb, J.; Ravenscroft, N.; et al. Shared values and deliberative valuation: Future directions. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, R.; Irvine, K.N.; Church, A.; Fish, R.; Ranger, S.; Kenter, J.O. Subjective well-being indicators for large-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banela, M.; Kitsiou, D. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A case study in Lesvos Island, Greece. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 246, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barianaki, E.A.; Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D.G. How to Incorporate Cultural Values and Heritage in Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP): A Systematic Review. Preprints 2023, 2023111761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.M.; van Beukering, P.; Balzan, M.; Broekx, S.; Liekens, I.; Marta-Pedroso, C.; Szkop, Z.; Vause, J.; Maes, J.; Santos-Martin, F. Report on Economic Mapping and Assessment Methods for Ecosystem Services. Deliverable D3.2 EU Horizon 2020 ESMERALDA Project, Grant Agreement No. 642007. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Martín, F.; Plieninger, T.; Torralba, M.; Fagerholm, N.; Vejre, H.; Luque, S.; Weibel, B.; Rabe, S.-E.; Balzan, M.; Czúcz, B. Report on Social Mapping and Assessment methods Deliverable D3.1EU Horizon 2020 ESMERALDA Project, Grant agreement No. 642007. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Martin, F.; Brander, L.; van Beukering, P.; Vihervaara, P.; Potschin-Young, M.; Liekens, I. Guidance report on a multi-tiered flexible methodology for integrating social, economic and biophysical methods. Deliverable D3.4. EU Horizon 2020 ESMERALDA Project, Grant agreement No. 642007. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vihervaara, P.; Mononen, L.; Nedkov, S.; Viinikka, A. Biophysical Mapping and Assessment Methods for Ecosystem Services. Deliverable D3.3 EU Horizon 2020 ESMERALDA Project, Grant Agreement No. 642007. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, L.S.; Vukomanovic, J.; Sills, E.O.; Sanchez, G. Cultural Ecosystem Services Caught in a ‘Coastal Squeeze’ between Sea Level Rise and Urban Expansion. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 66, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P. Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Review of Methods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrouse, B.C.; Semmens, D.J.; Ancona, Z.H. Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES): Open-Source Spatial Modeling of Cultural Services. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 148, 105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, Z.H.; Bagstad, K.J.; Le, L.; Semmens, D.J.; Sherrouse, B.C.; Murray, G.; Cook, P.S.; DiDonato, E. Spatial Social Value Distributions for Multiple User Groups in a Coastal National Park. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 222, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, R.; Hashimoto, S.; Basu, M.; Okuro, T.; Johnson, B.A.; Kumar, P.; Dhyani, S. Spatial Characterization of Non-Material Values across Multiple Coastal Production Landscapes in the Indian Sundarban Delta. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsma, F.J.; Mehnen, N.; Angelstam, P.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. Multi-Scale Mapping of Cultural Ecosystem Services in a Socio-Ecological Landscape: A Case Study of the International Wadden Sea Region. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1751–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, L.M.; Roebeling, P.; Villasante, S.; Bastos, M.I. Ecosystem Services Values and Changes across the Atlantic Coastal Zone: Considerations and Implications. Mar. Policy 2022, 145, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouttaki, I.; Khomalli, Y.; Maanan, M.; Bagdanavičiūtė, I.; Rhinane, H.; Kuriqi, A.; Pham, Q.B.; Maanan, M. A New Approach to Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services. Environments 2021, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Hausner, V.H. An Empirical Analysis of Cultural Ecosystem Values in Coastal Landscapes. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Elliott, M.; Ramos, S. Linking Modelling and Empirical Data to Assess Recreation Services Provided by Coastal Habitats: The Case of NW Portugal. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 162, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.G.; Kang, H.; Choi, S.-U. Assessment of Coastal Ecosystem Services for Conservation Strategies in South Korea. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Gasparatos, A. Community Values and Traditional Knowledge for Coastal Ecosystem Services Management in the “Satoumi” Seascape of Himeshima Island, Japan. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depellegrin, D.; Menegon, S.; Gusatu, L.; Roy, S.; Misiunė, I. Assessing Marine Ecosystem Services Richness and Exposure to Anthropogenic Threats in Small Sea Areas: A Case Study for the Lithuanian Sea Space. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, M.; Gomes, E.; Bogdzevič, K.; Kalinauskas, M.; Zhao, W.; Pereira, P. Mapping and Assessing Coastal Recreation Cultural Ecosystem Services Supply, Flow, and Demand in Lithuania. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Augé, A.A.; Sherren, K. Participatory Mapping to Elicit Cultural Coastal Values for Marine Spatial Planning in a Remote Archipelago. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Corbeira, C.; Barreiro, R.; Olmedo, M.; De la Cruz-Modino, R. Recreational Snorkeling Activities to Enhance Seascape Enjoyment and Environmental Education in the Islas Atlánticas de Galicia National Park (Spain). J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 272, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, C.; Calado, H.; McClintock, W.; Gil, A.; Fonseca, C. Mapping Recreational Ecosystem Services from Stakeholders’ Perspective in the Azores. One Ecosyst. 2021, 6, e65751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niz, W.C.; Laurino, I.R.A.; Freitas, D.M.D.; Rolim, F.A.; Motta, F.S.; Pereira-Filho, G.H. Modeling Risks in Marine Protected Areas: Mapping of Habitats, Biodiversity, and Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Southernmost Atlantic Coral Reef. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimienti, G.; Stithou, M.; Mura, I.D.; Mastrototaro, F.; D’Onghia, G.; Tursi, A.; Izzi, C.; Fraschetti, S. An Explorative Assessment of the Importance of Mediterranean Coralligenous Habitat to Local Economy: The Case of Recreational Diving. J. Environ. Account. Manag. 2017, 5, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retka, J.; Jepson, P.; Ladle, R.J.; Malhado, A.C.M.; Vieira, F.A.S.; Normande, I.C.; Souza, C.N.; Bragagnolo, C.; Correia, R.A. Assessing Cultural Ecosystem Services of a Large Marine Protected Area through Social Media Photographs. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 176, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Clemente, M.; Ettorre, B.; Poli, G. A Multidimensional Approach for Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) Assessment: The Cilento Coast Case Study (Italy). In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2021, 21st International Conference, Proceedings, Part VII. Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; pp. 490–503. [Google Scholar]

- Daymond, T.; Andrew, M.E.; Kobryn, H.T. Crowdsourcing Social Values Data: Flickr and Public Participation GIS Provide Different Perspectives of Ecosystem Services in a Remote Coastal Region. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 64, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Carver, S.; Ziv, G. Demographic, Natural and Anthropogenic Drivers for Coastal Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Falkland Islands. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocelli Pinheiro, R.; Triest, L.; Lopes, P.F.M. Cultural Ecosystem Services: Linking Landscape and Social Attributes to Ecotourism in Protected Areas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Dasgupta, R.; Takahashi, Y. Spatial Characterization of Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Ishigaki Island of Japan: A Comparison between Residents and Tourists. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 60, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenzel, D.; Martino, S. Assessing the Feasibility of Carbon Payments and Payments for Ecosystem Services to Reduce Livestock Grazing Pressure on Saltmarshes. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 225, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, E.; Kenter, J.O.; Graziano, M. The Effects of Aquaculture and Marine Conservation on Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Integrated Hedonic – Eudaemonic Approach. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo, L.J.; Sumeldan, J.; Sajorne, R.; Madarcos, J.R.; Goh, H.C.; Culhane, F.; Langmead, O.; Creencia, L. Cultural Values of Ecosystem Services from Coastal Marine Areas: Case of Taytay Bay, Palawan, Philippines. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 142, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, D.F.; Gerhardinger, L.C.; Vila-Nova, D.A.; de Carvalho, F.G.; Hanazaki, N. Integrated and Deliberative Multidimensional Assessment of a Subtropical Coastal-Marine Ecosystem (Babitonga Bay, Brazil). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 196, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Momtaz, S.; Gaston, T.; Moltschaniwskyj, N.A. Mapping the Intangibles: Cultural Ecosystem Services Derived from Lake Macquarie Estuary, New South Wales, Australia. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 243, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Motroni, S.; Santona, L.; Schirru, M. One Place, Different Communities’ Perceptions. In Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Asinara National Park (Italy). In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2021, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12955. [Google Scholar]

- Depietri, Y.; Ghermandi, A.; Campisi-Pinto, S.; Orenstein, D.E. Public Participation GIS versus Geolocated Social Media Data to Assess Urban Cultural Ecosystem Services: Instances of Complementarity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.R.; Friess, D.A. A Rapid Indicator of Cultural Ecosystem Service Usage at a Fine Spatial Scale: Content Analysis of Social Media Photographs. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 53, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Gone, K.P.; Wells, E.; Margeson, K.; Sherren, K. Modelling Cultural Ecosystem Services in Agricultural Dykelands and Tidal Wetlands to Inform Coastal Infrastructure Decisions: A Social Media Data Approach. Mar. Policy 2023, 150, 105533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Vieira, F.A.; Vinhas Santos, D.T.; Bragagnolo, C.; Campos-Silva, J.V.; Henriques Correia, R.A.; Jepson, P.; Mendes Malhado, A.C.; Ladle, R.J. Social Media Data Reveals Multiple Cultural Services along the 8.500 Km of Brazilian Coastline. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 214, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Charrahy, Z.; González-García, A. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services Provision: An Integrated Model of Recreation and Ecotourism Opportunities. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.M.; Wood, S.A.; Roh, Y.-H.; Kim, C.-K. The Geographic Spread and Preferences of Tourists Revealed by User-Generated Information on Jeju Island, South Korea. Land 2019, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell, T.L.; López-Carr, D.; Gelcich, S.; Gaines, S.D. The Importance of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Natural Resource-Dependent Communities: Implications for Management. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 44, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbleyth-Evans, J.; Lacy, S.N.; Aguirre-Muñoz, C.; Tredinnick-Rowe, J. Port Dumping and Participation in England: Developing an Ecosystem Approach through Local Ecological Knowledge. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 192, 105195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Olafsson, A.S. The Scale Effects of Landscape Variables on Landscape Experiences: A Multi-Scale Spatial Analysis of Social Media Data in an Urban Nature Park Context. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1271–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniatakou, S.; Berg, H.; Maneas, G.; Daw, T.M. Unravelling Diverse Values of Ecosystem Services: A Socio-Cultural Valuation Using Q Methodology in Messenia, Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlami, V.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Zogaris, S.; Kehayias, G.; Dimopoulos, P. Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Natura 2000 Network: Introducing Proxy Indicators and Conflict Risk in Greece. Land 2021, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Momtaz, S.; Gaston, T.; Moltschaniwskyj, N.A. A Systematic Quantitative Review of Coastal and Marine Cultural Ecosystem Services: Current Status and Future Research. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węsławski, J.M.; Andrulewicz, E.; Boström, C.; Horbowy, J.; Linkowski, T.; Mattila, J.; Olenin, S.; Piwowarczyk, J.; Skóra, K. Ecosystem goods, services and management. In Biological Oceanography of the Baltic Sea; Snoeijs-Leijonmalm, P., Schubert, H., Radziejewska, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Vergara, X.; Bozzeda, F.; Campos, G.; Subida, M.D.; Outeiro, L.; Villasante, S.; Fernández, M. Exploring Gaps in Mapping Marine Ecosystem Services: A Benchmark Analysis. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 192, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, S.S.K.; Van Teeffelen, A.J.A.; Verburg, P.H. Integrating Socio-Cultural Perspectives into Ecosystem Service Valuation: A Review of Concepts and Methods. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Benra Ochoa, F.; Rojas, F.; Díaz, G.I.; Carmona, A. Mapping Social Values of Ecosystem Services: What Is behind the Map? Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, art24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Maes, J. Mapping Ecosystem Services; Pensoft Publishers: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paracchini, M.L.; Zulian, G.; Kopperoinen, L.; Maes, J.; Schägner, J.P.; Termansen, M.; Zandersen, M.; Perez-Soba, M.; Scholefield, P.A.; Bidoglio, G. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Framework to Assess the Potential for Outdoor Recreation across the EU. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinke, Z.; Vári, Á.; Kovács, E.T. Value Transfer in Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services – Some Methodological Challenges. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 56, 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobstvogt, N.; Watson, V.; Kenter, J.O. Looking below the Surface: The Cultural Ecosystem Service Values of UK Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.; Cambridge, H. Interactive Online CH Mapping Portal. PrEseRvIng and Sustainably Governing Cultural Heritage and Landscapes in European Coastal and Maritime regionS, PERICLES_D3.1_v2.0 Dissemination Level: PU, 2019.

- Golding, N.; Black, B. Final Report from the DPLUS065 Mapping Falklands and South Georgia Coastal Margins for Spatial Planning Project, 2020. SAERI. 102p. Available online: https://Www.Darwininitiative.Org.Uk/Documents/DPLUS027/23882/DPLUS027%20FR%20-%20edited.Pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Patera, A.; Pataki, Z.; Kitsiou, D. Development of a webGIS Application to Assess Conflicting Activities in the Framework of Marine Spatial Planning. JMSE 2022, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudia, B.; Bürgi, M.; Le Du-Blayo, L.; Martín, M.; Girod, G.; von Hackwitz, K.; Howard, P.; Karro, K.; Kizos, T.; de Kleijn, M. D3.1 List and Documentation of Case Study Landscapes Selected for HERCULES. WP3 Landscape-Scale Case Studies (Short-Term History). 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trommler, K.; Plieninger, T. Sustainable futures for Europe’s heritage in cultural landscapes: Tools for Understanding, Managing, and Protecting Landscape Functions and Values; mid-term assessment report; Hercules, FP7, Collaborative Project: Berlin/Copenhagen. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinis, G.; Chalkidou, S.; Roustanis, T.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Chrysafis, I.; Karolos, I.-A.; Vagiona, D.; Kavvadia, A.; Dimopoulos, P.; Mitsopoulos, I. A National Scale Web Mapping Platform for Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services in Greece. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 78, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellach, C.; Carmon, D.; Teschner, N.; Boral, R. Legal-Institutional Instruments for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in the Mediterranean. Final Report, 2016, MARE NOSTRUM PROJECT. Available online: Https://Curs.Net.Technion.Ac.Il/Files/2018/11/Mare-Nostrum-Final-Report.Pdf.

- McClellandb, A. owards a Cross-Border Cultural Heritage Atlas for the North West: Data Availability, Webhosting and Guiding Principles for the GIS Mapping of Heritage Inventory and Other Datasets.; 1; National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis (NIRSA), Maynooth University Social Science Institute (MUSSI). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, A. Spaces for Public Participation: valuing the cross-border landscape in North West Ireland’. Ir. Geogr. 2019, 52, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Search 1 | Find Articles with these terms: | "marine spatial planning" OR "maritime spatial planning" OR "marine planning" OR "coastal planning" |

| AND Search in Title, Abstract, Keywords for: | "cultural ecosystem services" OR "cultural ecosystem values" OR "intangible benefits" OR "non-material benefits" | |

| Search 2 | Search in Title, Abstract, Keywords for: | ("cultural ecosystem services" OR "cultural ecosystem values" OR "intangible benefits" OR "non-material benefits") AND (marine OR coastal) AND (“participatory mapping” OR “Participatory GIS” OR PGIS OR “Public Participation GIS” OR PPGIS) |

| Search 3 | Projects, Report Summaries: | (“ecosystem services” OR “cultural ecosystem services” OR “cultural eco-system values” OR “cultural values” OR “landscape values” OR “intangible benefits” OR “non-material benefits” OR “natural heritage” OR “eco-heritage”) AND (“participatory mapping” OR “Participatory GIS” OR PGIS OR “Public Participation GIS” OR PPGIS OR “marine spatial planning” OR MSP) |

| Search 4 | Find Articles with these terms: | ("cultural ecosystem services" OR "cultural ecosystem values" OR "intangible benefits" OR "non-material benefits") AND (marine OR coastal) |

| AND Search in Title, Abstract, Keywords for: | "ecosystem services" AND (webGIS OR "web-GIS") |

| Criteria | Categories |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | without time frame |

| Who | scientific community, government/ regional/local authorities,other |

| Ocean/sea | NW Atlantic, West Mediterranean, etc. |

| Continent/country | Asia/China, Europe/UK, Australia/New Zealand, North America/USA, etc. |

| Scale of paper | basin-centered, national, regional (region of country, county of region, etc.), local (1 or more municipalities), coastal zone (landwards and seawards), multi-scale, comparative papers |

| Ecosystem assessed | coastal, marine, coastal and marine |

| MSP focused | yes, no |

| CES focused | Yes, no |

| Stakeholders category | residents, specific stakeholders, scientists, mixed groups of stakeholders, no stakeholder’s engagement |

| Mapping approaches & methods (focused on CES) | Social methods (participatory mapping, social media-based, etc.), Economic methods (hedonic pricing, value transfer, etc.), Mixed methods (mixed participatory mapping, other) |

| Valuation types & methods | Monetary (hedonic pricing, travel cost, deliberative valuation, etc.), Non-monetary (participatory mapping, personal interviews, questionnaires, etc.), Combination of both |

| Type of method | |

| Biophysical methods | They include direct (e.g., remote sensing and earth observation) or indirect measurement (remote sensing and earth observation derives, use of statistical data, spatial proxy methods) and modelling (e.g., macro-ecological models, statistical models, conceptual models). |

| Social methods | They measure individual and collective preferences for mapping and assessing ES (e.g., official statistics, personal interviews, participatory mapping, focus groups) |

| Economic methods | It is a group of methods that have been developed for estimating the economic value of ES (e.g., hedonic pricing, market value, value transfer); |

| Mixed methods | They refer to mapping approaches that link or integrate methods and information from different disciplines (biophysical, social, economic) |

| Participatory | Methods, Techniques, Tools | Software used |

|---|---|---|

| Decision making | Spatial Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis - SMCDA [GeoTOPSIS] (1), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) (2), Analytic Network Process (ANP) method (3), Strategic Options Development Analysis (SODA) approach (4), | QGIS (1), IDRISI SELVA (2), Super Decisions software (3), Decision Explorer software (4) |

| Web-based surveys | Google Maps platform, Scribble Maps, ESRI ’s Survey123, Greenmapper survey tool, SeaSketch | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).