Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Settings

4.2. Study Population

4.3. Covariates

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoang, U.; Stewart, R.; Goldacre, M.J. Mortality after hospital discharge for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: retrospective study of linked English hospital episode statistics, 1999-2006. BMJ 2011, 343, d5422–d5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlbeck, K.; Westman, J.; Nordentoft, M.; Gissler, M.; Laursen, T.M. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.-J.; Yeh, L.-L.; Chan, H.-Y.; Chang, C.-K. Transformation of excess mortality in people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Taiwan. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.-J.; Yeh, L.-L.; Chan, H.-Y.; Chang, C.-K. Excess mortality and shortened life expectancy in people with major mental illnesses in Taiwan. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, J.; Lönnqvist, J.; Wahlbeck, K.; Klaukka, T.; Niskanen, L.; Tanskanen, A.; Haukka, J. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet 2009, 374, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, T.M.; Wahlbeck, K.; Hällgren, J.; Westman, J.; Ösby, U.; Alinaghizadeh, H.; Gissler, M.; Nordentoft, M. Life Expectancy and Death by Diseases of the Circulatory System in Patients with Bipolar Disorder or Schizophrenia in the Nordic Countries. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e67133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, M.; Tiihonen, J.; Wildgust, H.; Beary, M.; Hodgson, R.; Kajantie, E.; Osmond, C.; Räikkönen, K.; Eriksson, J. Cardiovascular morbidity, mortality and pharmacotherapy in patients with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, T.M.; Mortensen, P.B.; MacCabe, J.H.; Cohen, D.; Gasse, C. Cardiovascular drug use and mortality in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a Danish population-based study. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, V.A.; McGrath, J.J.; Jablensky, A.; Badcock, J.C.; Waterreus, A.; Bush, R.; Carr, V.; Castle, D.; Cohen, M.; Galletly, C.; et al. Psychosis prevalence and physical, metabolic and cognitive co-morbidity: data from the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2163–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Sood, P.; Lally, J.; Smith, S.; Atakan, Z.; Ismail, K.; Greenwood, K.E.; Keen, A.; O’Brien, C.; Onagbesan, O.; Fung, C.; et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in people with established psychotic illnesses: baseline data from the IMPaCT randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, M.; Kolachalam, S.; Longoni, B.; Pintaudi, A.; Baldini, M.; Aringhieri, S.; Fasciani, I.; Annibale, P.; Maggio, R.; Scarselli, M. Atypical Antipsychotics and Metabolic Syndrome: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Differences. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, W.A.; Chung, C.P.; Murray, K.T.; Hall, K.; Stein, C.M. Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiihonen, J.; Lönnqvist, J.; Wahlbeck, K.; Klaukka, T.; Tanskanen, A.; Haukka, J. Antidepressants and the Risk of Suicide, Attempted Suicide, and Overall Mortality in a Nationwide Cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiihonen, J.; Haukka, J.; Taylor, M.; Haddad, P.M.; Patel, M.X.; Korhonen, P. A Nationwide Cohort Study of Oral and Depot Antipsychotics After First Hospitalization for Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crump, C.; Winkleby, M.A.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Jørgensen, M.; Mainz, J.; Carinci, F.; Thomsen, R.W.; Johnsen, S.P.; Tiihonen, J.; et al. Comorbidities and Mortality in Persons with Schizophrenia: A Swedish National Cohort Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Yeh, L.-L.; Pan, Y.-J. Exposure to psychotropic medications and mortality in schizophrenia: a 5-year national cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 5528–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torniainen, M.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Tanskanen, A.; Björkenstam, C.; Suvisaari, J.; Alexanderson, K.; Tiihonen, J. Antipsychotic Treatment and Mortality in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.I.; Vahia, I.; Reyes, P.; Diwan, S.; Bankole, A.O.; Palekar, N.; Kehn, M.; Ramirez, P. Focus on Geriatric Psychiatry: Schizophrenia in Later Life: Clinical Symptoms and Social Well-being. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, L.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folsom, D.P.; Lebowitz, B.D.; Lindamer, L.A.; Palmer, B.W.; Patterson, T.L.; Jeste, D.V. Schizophrenia in late life: emerging issues. Dialog- Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.I.; Meesters, P.D.; Zhao, J. New perspectives on schizophrenia in later life: implications for treatment, policy, and research. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, M.V. Schizophrenia Mortality: Barriers to Progress. Psychiatr. Q. 2019, 90, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.; Druss, B. The epidemiology of diabetes in psychotic disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, C.P.; Jones, L.; Woolson, R.F. Medical Comorbidity in Women and Men with Schizophrenia: A Population-Based Controlled Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Bortolato, B.; Rosson, S.; Santonastaso, P.; Thapa-Chhetri, N.; Fornaro, M.; Gallicchio, D.; Collantoni, E.; et al. Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality from Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Pooled and Specific Severe Mental Illness: A Large-Scale Meta-Analysis of 3,211,768 Patients and 113,383,368 Controls. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Croatto, G.; Schneider, L.K.; Rohani-Montez, S.C.; Fairley, L.; Smith, N.; Bitter, I.; Gorwood, P.; Taipale, H.; et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, M.J.; Peralta, V. Lack of Insight in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1994, 20, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablensky, A.; Sartorius, N.; Ernberg, G.; Anker, M.; Korten, A.; Cooper, J.E.; Day, R.; Bertelsen, A. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures A World Health Organization Ten-Country Study. Psychol. Med. Monogr. Suppl. 1992, 20, 1–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacro, J.P.; Dunn, L.B.; Dolder, C.R.; Leckband, S.G.; Jeste, D.V. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Medication Nonadherence in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterer, G. Why Do Patients with Schizophrenia Smoke? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šagud, M.; Vuksan-Ćusa, B.; Jakšić, N.; Mihaljević-Peleš, A.; Živković, M.; Vlatković, S.; Prgić, T.; Marčinko, D.; Wang, W. Nicotine dependence in Croatian male inpatients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US). Office on Smoking and Health The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta (GA).

- Jha, P.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Landsman, V.; Rostron, B.; Thun, M.; Anderson, R.N.; McAfee, T.; Peto, R. 21st-Century Hazards of Smoking and Benefits of Cessation in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Surgeon General (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta (GA); ISBN 9780160515767.

- Thun, M.J.; Apicella, L.F.; Henley, S.J. Smoking vs Other Risk Factors as the Cause of Smoking-Attributable Deaths. JAMA 2000, 284, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Ninou, A.; Samakouri, M. Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.; Mainz, J.; Egstrup, K.; Johnsen, S.P. Quality of Care and Outcomes of Heart Failure among Patients with Schizophrenia in Denmark. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harangozo, J.; Reneses, B.; Brohan, E.; Sebes, J.; Csukly, G.; López-Ibor, J.J.; Sartorius, N.; Rose, D.; Thornicroft, G. Stigma and discrimination against people with schizophrenia related to medical services. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Mehtälä, J.; Vattulainen, P.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. 20-Year Follow-up Study of Physical Morbidity and Mortality in Relationship to Antipsychotic Treatment in a Nationwide Cohort of 62,250 Patients with Schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, J.; Eriksson, S.V.; Gissler, M.; Hällgren, J.; Prieto, M.L.; Bobo, W.V.; Frye, M.A.; Erlinge, D.; Alfredsson, L.; Ösby, U. Increased cardiovascular mortality in people with schizophrenia: a 24-year national register study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoodee, H.; Al Khalili, M.; Theik, N.W.Y.; Raji, O.E.; Shenwai, P.; Shah, R.; Kalluri, S.R.; Bhutta, T.H.; Khan, S. The Outcomes of Acute Coronary Syndrome in Patients Suffering from Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e16998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, M.; De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Di Palo, K.; Munir, H.; Music, S.; Piña, I.; Ringen, P.A. Severe Mental Illness and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R. Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: An Overview. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72 (Suppl. 1), 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; Correll, C.U. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 8, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Probst, M.; De Hert, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gaughran, F.; Lally, J.; Stubbs, B. Diabetes Mellitus in People with Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Large Scale Meta-Analysis. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kredentser, M.S.; Martens, P.J.; Chochinov, H.M.; Prior, H.J. Cause and Rate of Death in People with Schizophrenia across the Lifespan: A Population-Based Study in Manitoba, Canada. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaslahti, T.; Alanen, H.-M.; Hakko, H.; Isohanni, M.; Häkkinen, U.; Leinonen, E. Mortality and causes of death in older patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, I.V.; Diwan, S.; Bankole, A.O.; Kehn, M.; Nurhussein, M.; Ramirez, P.; Cohen, C.I. Adequacy of Medical Treatment among Older Persons with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brink, M.; Green, A.; Bojesen, A.B.; Lamberti, J.S.; Conwell, Y.; Andersen, K. Physical Health, Medication, and Healthcare Utilization among 70-Year-Old People with Schizophrenia: A Nationwide Danish Register Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masand, P.S. Side effects of antipsychotics in the elderly. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61 (Suppl. 8), 43–49, discussion 50-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy, P.; Harugeri, A. Elderly patients’ participation in clinical trials. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2015, 6, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.S.; Schneeweiss, S.; Avorn, J.; Fischer, M.A.; Mogun, H.; Solomon, D.H.; Brookhart, M.A. Risk of Death in Elderly Users of Conventional vs. Atypical Antipsychotic Medications. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huybrechts, K.F.; Gerhard, T.; Crystal, S.; Olfson, M.; Avorn, J.; Levin, R.; Lucas, J.A.; Schneeweiss, S. Differential risk of death in older residents in nursing homes prescribed specific antipsychotic drugs: population based cohort study. BMJ 2012, 344, e977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Insurance Administration. 2016. Introduction of the System of the Tenth Edition of the International Classification of Diseases for National Health Insurance (ICD-10-CM/PCS). Available online: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Resource/webdata/27361_3_%E5%85%A8%E6%B0%91%E5%81%A5%E5%BA%B7%E4%BF%9D%E9%9A%AA%E5%9C%8B%E9%9A%9B%E7%96%BE%E7%97%85%E5%88%86%E9%A1%9E%E7%AC%AC%E5%8D%81%E7%89%88(ICD-10-CM-PCS)%E5%88%B6%E5%BA%A6%E7%B0%A1%E4%BB%8B%E5%8F%8A%E8%AA%AA%E6%98%8E.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. 2012. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment, 16th edition. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/filearchive/publications/1_2013guidelines.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

| Patients with schizophrenia (n=102,964) |

Control sample (n=102,964) | Significance | Elderly patients with schizophrenia (n=6433) |

Control sample (n=7485) |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old)[mean (SD)] | 44.8 (13.2) | 44.8(13.6) | F=720.946** | 73.6 (6.7) | 72.9 (6.5) | F=40.762** |

| Gender [n (%)] | χ2=0.0** | χ2=0.079 | ||||

| Female | 48,813 (47.4) | 48,813(47.4) | 3843 (59.7) | 4489 (60.0) | ||

| Male | 54,151 (52.6) | 54,151(52.6) | 2590 (40.3) | 2996 (40.0) | ||

|

Lower-income household [n (%)] |

13,129 (12.8) | 778(0.8) | χ2=107017.511** | 948 (14.7) | 58 (0.8) | χ2=1005.687** |

| With catastrophic illness certificate [n (%)] | 74,540 (72.4) | 2673(2.6) | χ2=107017.511** | 4049 (62.9) | 602 (8.0) | χ2=4686.137** |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||

| COPD [n (%)] | 8796 (8.5) | 5055 (4.9) | χ2=1083.264** | 1408 (21.9) | 1085 (14.5) | χ2=128.549** |

| CVD [n (%)] | 10575 (10.3) | 9199 (8.9) | χ2=105.922** | 2151 (33.4) | 2726 (36.4) | χ2=13.520** |

| Cancer [n (%)] | 1642(1.6) | 2165(2.1) | χ2=73.202** | 309 (4.8) | 503 (6.7) | χ2=23.136** |

| DM [n (%)] | 11261(10.9) | 7001(6.8) | χ2=1090.437** | 1477 (23.0) | 1812 (24.2) | χ2=39.0484 |

| RD [n (%)] | 2414(2.3) | 2014(2.0) | χ2=36.928** | 510 (7.9) | 560 (7.5) | χ2=39.0484 |

| Death [n (%)] | χ2=2691.217** | χ2=517.351** | ||||

| All causes | 7,730 (7.5) | 2,593 (2.5) | 2053 (31.9) | 1168 (15.6) | ||

| Natural causes | 6,176 (6.0) | 843 (0.8) | χ2=695.821** | 1239 (19.3) | 475 (6.3) | χ2=161.784** |

| Cancer | 1,083 (1.1) | 909 (0.88) | 258 (4.0) | 320 (4.3) | ||

| CVD | 1,248 (1.2) | 446 (0.43) | 384 (6.0) | 247 (3.3) | ||

| DM | 449 (0.4) | 152 (0.15) | 111 (1.7) | 86 (1.1) | ||

| Unnatural causes | 1,258 (1.2) | 149 (0.14) | 33 (0.5) | 33 (0.4) | ||

| Suicide | 798 (0.8) | 68 (0.07) | 15 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | ||

| Unknown | 296 (0.3) | 26 (0.03) | 13 (0.2) | 3 (0.0) | ||

| Follow-up days [mean (SD)] | 1735.52 (231.67) | 1741.79 (174.7) | F=261.113** | 1491.12(529.14) | 1655.51(379.63) | F=104.75** |

| No exposure | Low exposure | Moderate exposure | High exposure | |||||

| Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| Patients with schizophrenia (n=102,964) n (%) | 8,733 (8.5%) | 33,403 (32.4%) | 41,811 (40.6%) | 19,017 (18.5%) | ||||

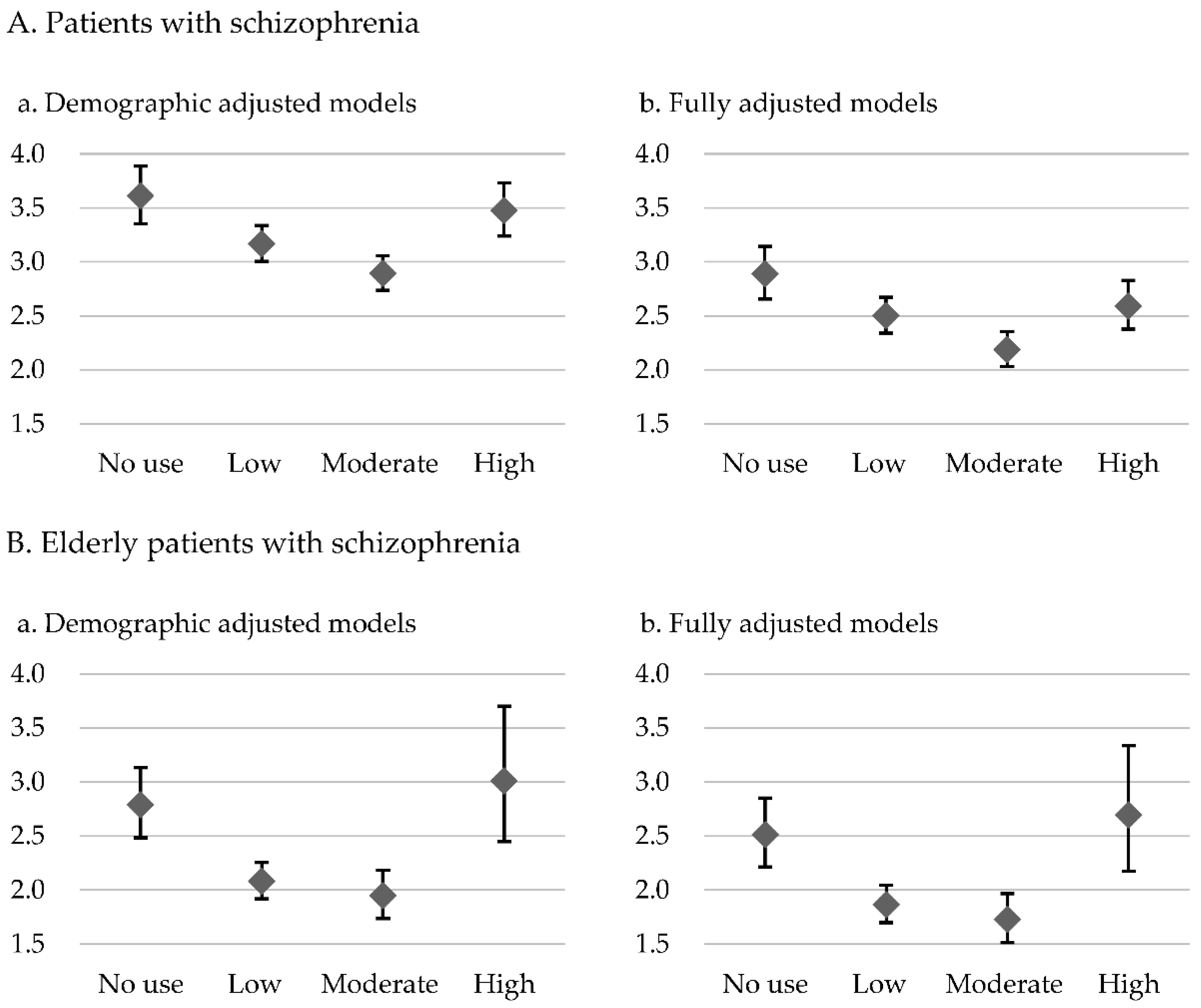

| Overall mortality | 3.610 | 3.353-3.886** | 3.167 | 3.005-3.337** | 2.892 | 2.737-3.056** | 3.475 | 3.238-3.730** |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 3.370 | 2.815-4.035** | 2.907 | 2.559-3.304** | 2.856 | 2.492-3.272** | 3.529 | 2.952-4.218** |

| Elderly patients with schizophrenia (n=6,433) n (%) | 944 (14.7%) | 3,520 (54.7%) | 1,636 (25.4%) | 333(5.2%) | ||||

| Overall mortality | 2.789 | 2.483-3.133** | 2.080 | 1.917-2.256** | 1.946 | 1.735-2.183** | 3.010 | 2.448-3.701** |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2.536 | 1.952-3.295** | 1.885 | 1.572-2.259** | 1.513 | 1.148-1.996** | 2.953 | 1.865-4.674** |

| No exposure | Low exposure | Moderate exposure | High exposure | |||||

| Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| Patients with schizophrenia (n=102,964) n (%) | 8,733 (8.5%) | 33,403 (32.4%) | 41,811 (40.6%) | 19,017 (18.5%) | ||||

| Overall mortality | 2.888 | 2.654-3.142** | 2.500 | 2.340-2.671** | 2.187 | 2.032-2.354** | 2.591 | 2.375-2.826** |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2.956 | 2.402-3.639** | 2.462 | 2.092-2.898** | 2.327 | 1.938-2.795** | 2.874 | 2.309-3.577** |

| Elderly patients with schizophrenia (n=6,433) n (%) | 944 (14.7%) | 3,520 (54.7%) | 1,636 (25.4%) | 333(5.2%) | ||||

| Overall mortality | 2.511 | 2.214-2.849** | 1.862 | 1.696-2.044** | 1.727 | 1.517-1.965** | 2.692 | 2.172-3.337** |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2.392 | 1.796-3.185** | 1.713 | 1.388-2.114** | 1.359 | 0.996-1.854** | 2.784 | 1.724-4.495** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).