Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Genetic factors in common diseases of white shrimp, striped catfish and yellowtail kingfish

1.1. Genetic susceptibility

1.2. Genetic correlations of disease resistance with complex traits

2. Selection to enhance disease resistance.

2.1. Genetic gains

2.2. Effects of selection for enhanced disease resistance on commercial traits

2.2.1. Effects on survival and growth

2.2.2. Effects on immune response in shrimp

2.2.3. Effects on immunological parameters in striped catfish

3. Alternative selection criteria to enhance disease resistance.

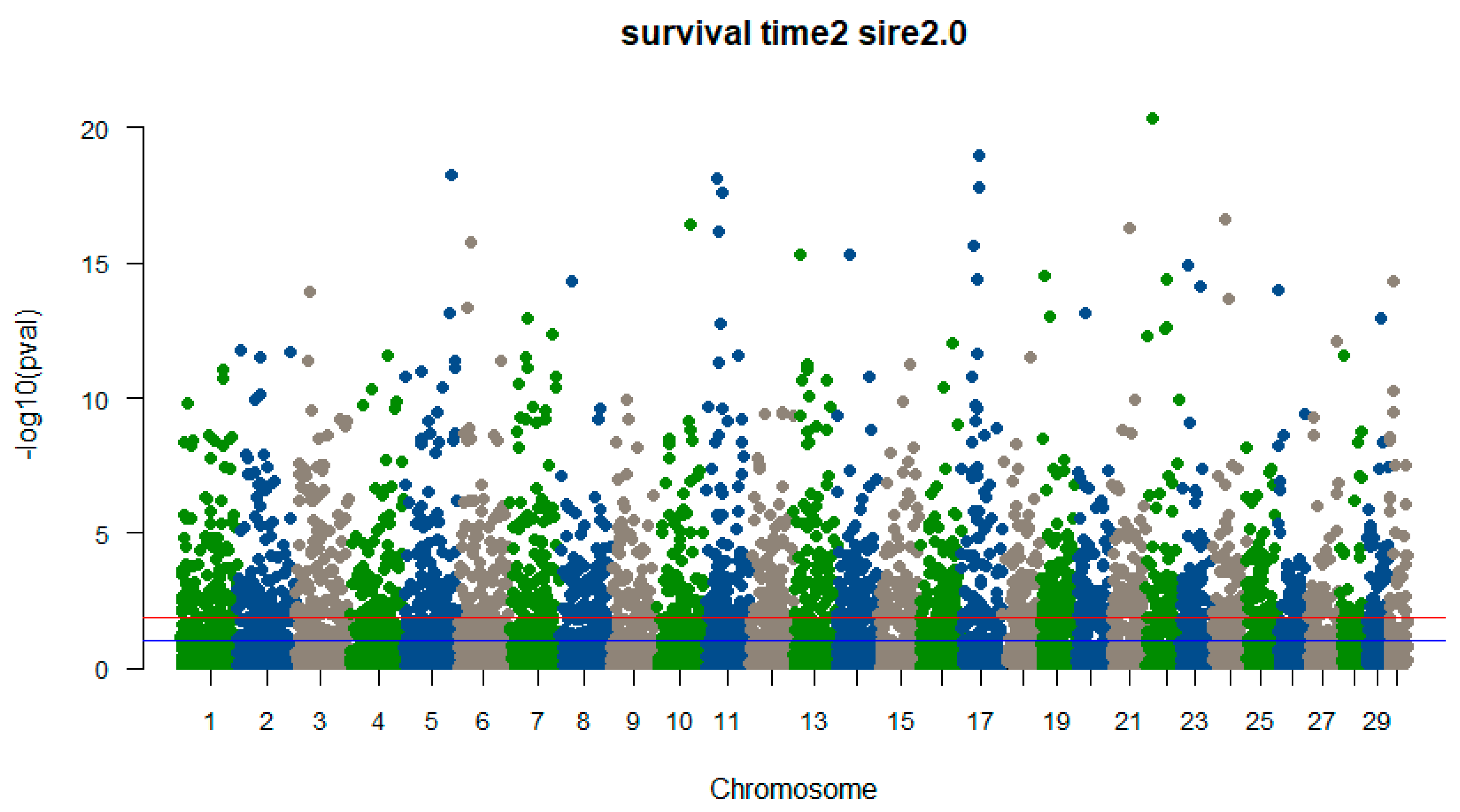

4. Genetic variants for disease resistance

5. Genomic prediction to enable genome-based selection

6. Omics technologies

6.1. Transcriptomics

6.2. Metagenomics

6.3. Other omics

7. Future directions

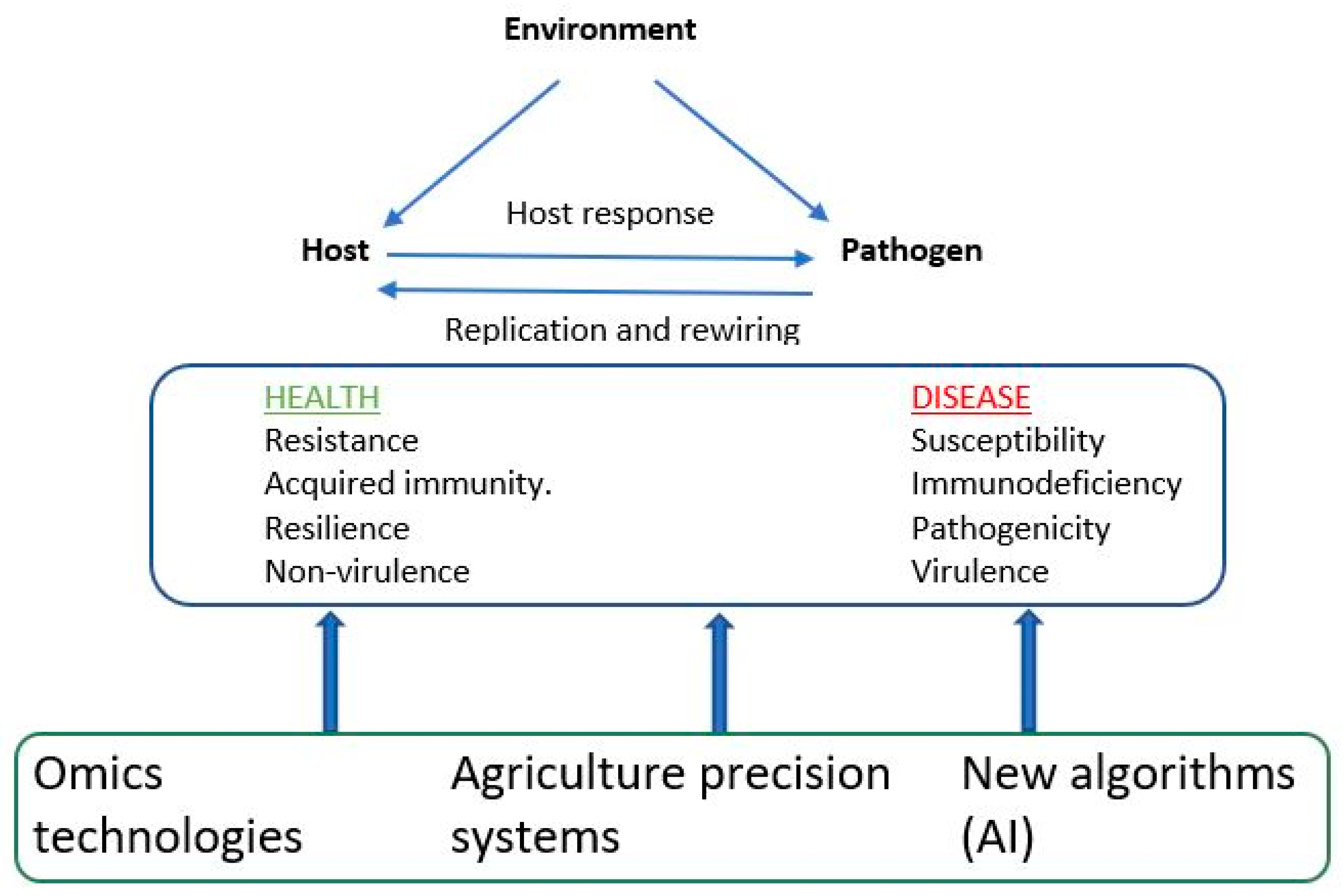

7.1. Precision agriculture systems and artificial intelligence

7.2. Enhancing overall immune response and epidemiological host traits

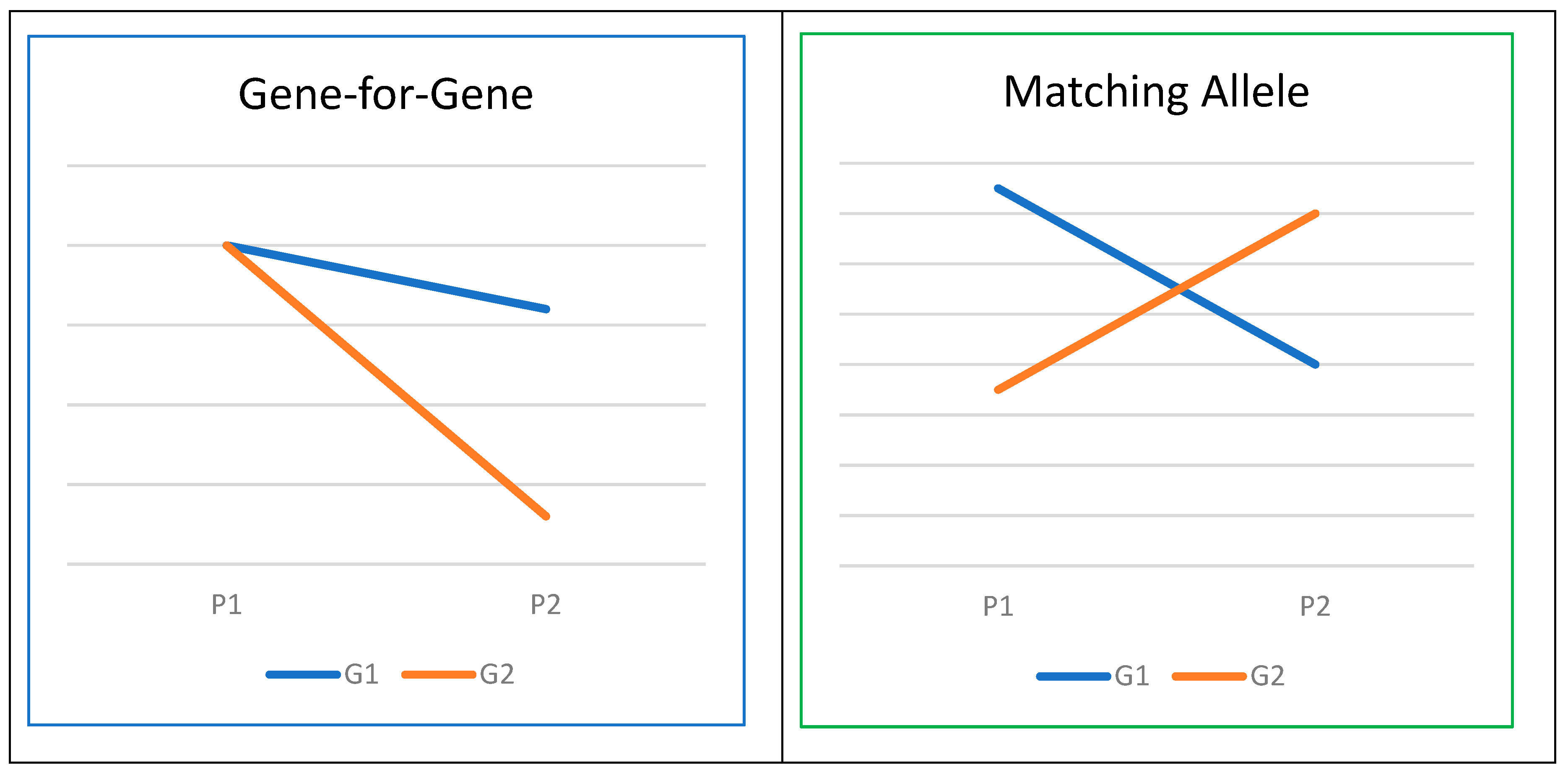

7.3. Host-pathogen interactions

7.4. Genomic surveillance in genetic enhancement programs

8. Concluding remarks and suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hutson, K.S.; Davidson, I.C.; Bennett, J.; Poulin, R.; Cahill, P.L. Assigning cause for emerging diseases of aquatic organisms. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J.; Mohan, C.V. Viral disease emergence in shrimp aquaculture: origins, impact and the effectiveness of health management strategies. Reviews in Aquaculture 2009, 1, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, C.A.; Eakin, C.M.; Friedman, C.S.; Froelich, B.; Hershberger, P.K.; Hofmann, E.E.; Petes, L.E.; Prager, K.C.; Weil, E.; Willis, B.L.; et al. Climate Change Influences on Marine Infectious Diseases: Implications for Management and Society. Annual Review of Marine Science 2014, 6, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.E.; Mahmud, A.S.; Miller, I.F.; Rajeev, M.; Rasambainarivo, F.; Rice, B.L.; Takahashi, S.; Tatem, A.J.; Wagner, C.E.; Wang, L.-F.; et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altizer, S.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kutz, S.; Harvell, C.D. Climate Change and Infectious Diseases: From Evidence to a Predictive Framework. Science 2013, 341, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascarano, M.C.; Stavrakidis-Zachou, O.; Mladineo, I.; Thompson, K.D.; Papandroulakis, N.; Katharios, P. Mediterranean Aquaculture in a Changing Climate: Temperature Effects on Pathogens and Diseases of Three Farmed Fish Species. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Soto, E.; Gross, J. Disease prevention and mitigation in US finfish aquaculture: A review of current approaches and new strategies. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondad-Reantaso, M.G.; MacKinnon, B.; Karunasagar, I.; Fridman, S.; Alday-Sanz, V.; Brun, E.; Le Groumellec, M.; Li, A.; Surachetpong, W.; Karunasagar, I.; et al. Review of alternatives to antibiotic use in aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 1421–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangkahart, E.; Lee, P.-T.; Chong, C.-M.; Yamamoto, F. 10 Safety and Efficacy of Vaccines in Aquaculture. Fish Vaccines: Health Management for Sustainable Aquaculture 2023, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, H.; Thomas, J. A review on the recent advances and application of vaccines against fish pathogens in aquaculture. Aquacult. Int. 2022, 30, 1971–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.; Black, K.D.; Burnell, G.; Cross, T.; Culloty, S.; Ekaratne, S.; Furness, B.; Mulcahy, M.; Thetmeyer, H. Aquaculture: the ecological issues; John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, N.A.; Robledo, D.; Sveen, L.; Daniels, R.R.; Krasnov, A.; Coates, A.; Jin, Y.H.; Barrett, L.T.; Lillehammer, M.; Kettunen, A.H.; et al. Applying genetic technologies to combat infectious diseases in aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 491–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, R.D.; Bean, T.P.; Macqueen, D.J.; Gundappa, M.K.; Jin, Y.H.; Jenkins, T.L.; Selly, S.L.C.; Martin, S.A.M.; Stevens, J.R.; Santos, E.M.; et al. Harnessing genomics to fast-track genetic improvement in aquaculture. Nature Reviews Genetics 2020, 21, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, D.; Mackay, T. Introduction to quantitative genetics; Longmans Green: Longmans Green, 1996; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, R.R.; Taylor, R.S.; Robledo, D.; Macqueen, D.J. Single cell genomics as a transformative approach for aquaculture research and innovation. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 1618–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Xiang, J.; Li, F. Recent advances in crustacean genomics and their potential application in aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 1501–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, T.; De Rybel, B.; Vandepoele, K. Charting plant gene functions in the multi-omics and single-cell era. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Genini, S.; Bishop, S.C.; Giuffra, E. An assessment of opportunities to dissect host genetic variation in resistance to infectious diseases in livestock. animal 2009, 3, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of genetic parameters for complex quantitative traits in aquatic animal species. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegård, J.; Baranski, M.; Gjerde, B.; Gjedrem, T. Methodology for genetic evaluation of disease resistance in aquaculture species: challenges and future prospects. Aquacult. Res. 2011, 42, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N. Genetic improvement for important farmed aquaculture species with a reference to carp, tilapia and prawns in Asia: achievements, lessons and challenges. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégremont, L.; Garcia, C.; Allen, S.K. Genetic improvement for disease resistance in oysters: A review. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 131, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.T.; Hung, N.H.; Ninh, N.H.; Nguyen, N.H. Selection for improved white spot syndrome virus resistance increased larval survival and growth rate of Pacific whiteleg shrimp, Liptopenaeus vannamei. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2019, 166, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.M.; De Donato, M.; Bhat, B.A.; Diallo, A.B.; Peters, S.O. Editorial: Omics technologies in livestock improvement: From selection to breeding decisions. Frontiers in Genetics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronyk, P.M.; de Alwis, R.; Rockett, R.; Basile, K.; Boucher, Y.F.; Pang, V.; Sessions, O.; Getchell, M.; Golubchik, T.; Lam, C.; et al. Advancing pathogen genomics in resource-limited settings. Cell Genomics 2023, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.H.; Hayes, B.J.; Goddard, M.E. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics 2001, 157, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, J.M.; Barría, A.; López, M.E.; Moen, T.; Garcia, B.F.; Yoshida, G.M.; Xu, P. Genome-wide association and genomic selection in aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 645–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Dong, T.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.; Tian, Z.; Sun, A.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hu, H. Genomic selection and its research progress in aquaculture breeding. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, 15, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M. Genomic selection: prediction of accuracy and maximisation of long term response. Genetica 2009, 136, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Agarwal, D.; Bhat, T.A.; Khan, I.A.; Zafar, I.; Kumar, S.; Amin, A.; Sundaray, J.K.; Qadri, T. Bioinformatics approaches and big data analytics opportunities in improving fisheries and aquaculture. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 233, 123549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannejal, A.D.; Divyashree, M.; Kumar, D.V.; Nithin, M.S.; Rai, P. Fish Microbiome and Metagenomics. In Microbiome of Finfish and Shellfish; Diwan, A., Harke, S.N., Panche, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlopoulos, G.A.; Baltoumas, F.A.; Liu, S.; Selvitopi, O.; Camargo, A.P.; Nayfach, S.; Azad, A.; Roux, S.; Call, L.; Ivanova, N.N.; et al. Unraveling the functional dark matter through global metagenomics. Nature 2023, 622, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, B.; Bruce, T.J.; Wise, A.L.; Zeng, P.; Cao, G.; Simora, R.M.C.; Bern, L.; Shang, M.; Li, S.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 microinjection of transgenic embryos enhances the dual-gene integration efficiency of antimicrobial peptide genes for bacterial resistance in channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrani, A.; Liu, S. Harnessing CRISPR/Cas9 system to improve economic traits in aquaculture species. Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorgen-Ritchie, M.; Uren Webster, T.; McMurtrie, J.; Bass, D.; Tyler, C.R.; Rowley, A.; Martin, S.A.M. Microbiomes in the context of developing sustainable intensified aquaculture. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1200997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natnan, M.E.; Mayalvanan, Y.; Jazamuddin, F.M.; Aizat, W.M.; Low, C.-F.; Goh, H.-H.; Azizan, K.A.; Bunawan, H.; Baharum, S.N. Omics Strategies in Current Advancements of Infectious Fish Disease Management. Biology 2021, 10, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.T.; Sang, N.V.; Trong, T.Q.; Duy, N.H.; Dang, N.T.; Nguyen, N.H. Breeding for improved resistance to Edwardsiella ictaluri in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus): Quantitative genetic parameters. J. Fish Dis. 2019, 42, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.T.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Wayne, K.; Nguyen, N.H. Genetic variation in disease resistance against White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) in Liptopenaeus vannamei. Frontiers in Genetics 2019, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitterle, T.; Rye, M.; Salte, R.; Cock, J.; Johansen, H.; Lozano, C.; Arturo Suárez, J.; Gjerde, B. Genetic (co)variation in harvest body weight and survival in Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei under standard commercial conditions. Aquaculture 2005, 243, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premachandra, H.K.A.; Nguyen, N.H.; Miller, A.; D'Antignana, T.; Knibb, W. Genetic parameter estimates for growth and non-growth traits and comparison of growth performance in sea cages vs land tanks for yellowtail kingfish Seriola lalandi. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Vu, N.T. Threshold models using Gibbs sampling and machine learning genomic predictions for skin fluke disease recorded under field environment in yellowtail kingfish Seriola lalandi. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henryon, M.; Jokumsen, A.; Berg, P.; Lund, I.; Pedersen, P.; Olesen, N.; Slierendrecht, W. Genetic variation for growth rate, feed conversion efficiency, and disease resistance exists within a farmed population of rainbow trout. Aquaculture 2002, 209, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitterle, T.; Salte, R.; Gjerde, B.; Cock, J.; Johansen, H.; Salazar, M.; Lozano, C.; Rye, M. Genetic (co)variation in resistance to White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) and harvest weight in Penaeus (Litopenaeus) vannamei. Aquaculture 2005, 246, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, J.M.; Lhorente, J.P.; Bassini, L.N.; Oyarzún, M.; Neira, R.; Newman, S. Genetic co-variation between resistance against both Caligus rogercresseyi and Piscirickettsia salmonis, and body weight in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 2014, 433, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuthaworn, C.; Nguyen, N.H.; Quinn, J.; Knibb, W. Moderate heritability of hepatopancreatic parvovirus titre suggests a new option for selection against viral diseases in banana shrimp (Fenneropenaeus merguiensis) and other aquaculture species. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2016, 48, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Ninh, N.H.; Hung, N.H. Evaluation of two genetic lines of Pacific White leg shrimp Liptopenaeus vannamei selected in tank and pond environments. Aquaculture 2020, 516, 734522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjedrem, T.; Rye, M. Selection response in fish and shellfish: a review. Reviews in Aquaculture 2018, 10, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Premachandra, H.; Kilian, A.; Knibb, W. Genomic prediction using DArT-Seq technology for yellowtail kingfish Seriola lalandi. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trang, T.T. Genetic and genomic approaches to select for improved disease resistance against White spot syndrome virus in Whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Mahapatra, K.D.; Saha, J.N.; Barat, A.; Sahoo, M.; Mohanty, B.R.; Gjerde, B.; Ødegård, J.; Rye, M.; Salte, R. Family association between immune parameters and resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila infection in the Indian major carp, Labeo rohita. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Sang, N.; Dung, T.T.P.; Phuong, V.H.; Nguyen, N.H.; Thinh, N.H. Immune response of selective breeding striped catfish families (Pangasiandon hypophthalmus) to Edwardsiella ictaluri after challenge. Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strømsheim, A.; Eide, D.M.; Fjalestad, K.T.; Larsen, H.J.S.; Røed, K.H. Genetic variation in the humoral immune response in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) against Aeromonas salmonicida A-layer. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1994, 41, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisapoome, P.; Chatchaiphan, S.; Bunnoy, A.; Koonawootrittriron, S.; Na-Nakorn, U. Heritability of immunity traits and disease resistance of bighead catfish, Clarias macrocephalus Günther, 1864. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røed, K.H.; Fevolden, S.E.; Fjalestad, K.T. Disease resistance and immune characteristics in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) selected for lysozyme activity. Aquaculture 2002, 209, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Rauta, P.R.; Mohanty, B.R.; Mahapatra, K.D.; Saha, J.N.; Rye, M.; Eknath, A.E. Selection for improved resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila in Indian major carp Labeo rohita: Survival and innate immune responses in first generation of resistant and susceptible lines. Fish and Shellfish Immunology 2011, 31, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Rastas, P.M.A.; Premachandra, H.K.A.; Knibb, W. First High-Density Linkage Map and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Significantly Associated With Traits of Economic Importance in Yellowtail Kingfish Seriola lalandi. Frontiers in Genetics 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos-López, O.A.; Montesinos-López, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Barrón-López, J.A.; Martini, J.W.; Fajardo-Flores, S.B.; Gaytan-Lugo, L.S.; Santana-Mancilla, P.C.; Crossa, J.J.B.g. A review of deep learning applications for genomic selection. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Yin, D.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S. HIBLUP: an integration of statistical models on the BLUP framework for efficient genetic evaluation using big genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 3501–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.T.; Phuc, T.H.; Oanh, K.T.P.; Van Sang, N.; Trang, T.T.; Nguyen, N.H. Accuracies of genomic predictions for disease resistance of striped catfish to Edwardsiella ictaluri using artificial intelligence algorithms. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Vu, N.T.; Patil, S.S.; Sandhu, K.S. Multivariate genomic prediction for commercial traits of economic importance in Banana shrimp Fenneropenaeus merguiensis. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daetwyler, H.D.; Calus, M.P.; Pong-Wong, R.; de los Campos, G.; Hickey, J.M. Genomic prediction in animals and plants: simulation of data, validation, reporting, and benchmarking. Genetics 2013, 193, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.; Knibb, W.; Nguyen, N.H.; Elizur, A. Transcriptional Profiling of Banana Shrimp Fenneropenaeus merguiensis with Differing Levels of Viral Load. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016, 56, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerenius, L.; Lee, B.L.; Söderhäll, K. The proPO-system: pros and cons for its role in invertebrate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2008, 29, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.J.; Cho, H.K.; Park, E.M.; Hong, G.E.; Kim, Y.O.; Nam, B.H.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, S.J.; Han, H.S.; Jang, I.K.; et al. Molecular cloning of Kazal-type proteinase inhibitor of the shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009, 26, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donpudsa, S.; Ponprateep, S.; Prapavorarat, A.; Visetnan, S.; Tassanakajon, A.; Rimphanitchayakit, V. A Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitor SPIPm2 from the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon is involved in antiviral responses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2010, 34, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanEvery, H.; Franzosa, E.A.; Nguyen, L.H.; Huttenhower, C. Microbiome epidemiology and association studies in human health. Nature Reviews Genetics 2023, 24, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.J.; Sasson, G.; Garnsworthy, P.C.; Tapio, I.; Gregson, E.; Bani, P.; Huhtanen, P.; Bayat, A.R.; Strozzi, F.; Biscarini, F.; et al. A heritable subset of the core rumen microbiome dictates dairy cow productivity and emissions. Science Advances 2019, 5, eaav8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle-García, J.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Zingaretti, L.M.; Quintanilla, R.; Ballester, M.; Pérez-Enciso, M. On the holobiont ‘predictome’ of immunocompetence in pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Wölk, M.; Jukes, G.; Mendivelso Espinosa, K.; Ahrends, R.; Aimo, L.; Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Andrews, S.; Andrews, R.; Bridge, A.; et al. Guiding the choice of informatics software and tools for lipidomics research applications. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguet, F.; Alasoo, K.; Li, Y.I.; Battle, A.; Im, H.K.; Montgomery, S.B.; Lappalainen, T. Molecular quantitative trait loci. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2023, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, K.; Joshi, P.; Acharya, K.P.; Ramena, G. Emerging technologies revolutionising disease diagnosis and monitoring in aquatic animal health. Reviews in Aquaculture 2023, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazi, V.; Marques, C. Industry 4.0-based smart systems in aquaculture: A comprehensive review. Aquacult. Eng. 2023, 103, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu, O.; Blanco, A.; Bouza, C.; Martínez, P. Integration of host-pathogen functional genomics data into the chromosome-level genome assembly of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Aquaculture 2023, 564, 739067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaga-Maldonado, E.P.; Montaldo, H.H.; Castillo-Juárez, H.; Campos-Montes, G.R.; Martínez-Ortega, A.; Quintana-Casares, J.C.; Montoya-Rodríguez, L.; Betancourt-Lozano, M.; Lozano-Olvera, R.; Vázquez-Peláez, C. Crossbreeding effects for White Spot Disease resistance in challenge tests and field pond performance in Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei involving susceptible and resistance lines. Aquaculture 2020, 516, 734527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Razzaq, H.; Noorullah, M.; Ahmad, M.; Zuberi, A. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity, growth performance, disease resistance and expression of growth and immune related genes among five different stocks of Labeo rohita (Hamilton, 1822). Aquaculture 2023, 567, 739277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallard, B.A.; Emam, M.; Paibomesai, M.; Thompson-Crispi, K.; Wagter-Lesperance, L. Genetic selection of cattle for improved immunity and health. Jap. J. Vet. Res. 2015, 63, S37–S44. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley, C.M.; Marion, G.; Bishop, S.C.; Bailey, R.I.; Doeschl-Wilson, A.B. Estimating individuals’ genetic and non-genetic effects underlying infectious disease transmission from temporal epidemic data. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulst, A.D.; Bijma, P.; De Jong, M.C.M. Can breeders prevent pathogen adaptation when selecting for increased resistance to infectious diseases? Genet. Sel. Evol. 2022, 54, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doeschl-Wilson, A.; Knap, P.W.; Opriessnig, T.; More, S.J. Review: Livestock disease resilience: from individual to herd level. Animal 2021, 15, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijma, P.; Hulst, A.D.; de Jong, M.C. The quantitative genetics of the prevalence of infectious diseases: hidden genetic variation due to Indirect Genetic Effects dominates heritable variation and response to selection. Genetics 2022, 220, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghof, T.V.; Poppe, M.; Mulder, H.A. Opportunities to improve resilience in animal breeding programs. Frontiers in genetics 2019, 9, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Santos, A.; Willink, B.; Nowak, K.; Civitello, D.J.; Gillespie, T.R. Host–pathogen interactions under pressure: A review and meta-analysis of stress-mediated effects on disease dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellier, A.; Brown, J.K.; Boots, M.; John, S. Theory of Host–Parasite Coevolution: From Ecology to Genomics. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Råberg, L. Human and pathogen genotype-by-genotype interactions in the light of coevolution theory. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, E.; Fields, P.D.; Ebert, D. Uncovering the Genomic Basis of Infection Through Co-genomic Sequencing of Hosts and Parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrall, P.H.; Barrett, L.G.; Dodds, P.N.; Burdon, J.J. Epidemiological and Evolutionary Outcomes in Gene-for-Gene and Matching Allele Models. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napier, J.D.; Heckman, R.W.; Juenger, T.E. Gene-by-environment interactions in plants: Molecular mechanisms, environmental drivers, and adaptive plasticity. The Plant Cell 2022, 35, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.B.; Tolonen, A.C.; Xavier, R.J. Human genetic variation and the gut microbiome in disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017, 18, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, X.; Song, L.; Yu, G.; Vogtmann, E.; Goedert, J.J.; Abnet, C.C.; Landi, M.T.; Shi, J. MicrobiomeGWAS: A Tool for Identifying Host Genetic Variants Associated with Microbiome Composition. Genes 2022, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangavarapu, K.; Latif, A.A.; Mullen, J.L.; Alkuzweny, M.; Hufbauer, E.; Tsueng, G.; Haag, E.; Zeller, M.; Aceves, C.M.; Zaiets, K.; et al. Outbreak.info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stärk, K.D.C.; Pękala, A.; Muellner, P. Use of molecular and genomic data for disease surveillance in aquaculture: Towards improved evidence for decision making. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2019, 167, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J.L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Rokas, A. Incongruence in the phylogenomics era. Nature Reviews Genetics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, N.; Joseph, A.; Sasi, A.; Mujeeb, B.; Baiju, J.E.; Syrus, E.C.; Paul, N.M. 1 Understanding Vaccine Development in Aquaculture. In Fish Vaccines: Health Management for Sustainable Aquaculture; CRC Press, 2023; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harshitha, M.; Nayak, A.; Disha, S.; Akshath, U.S.; Dubey, S.; Munang’andu, H.M.; Chakraborty, A.; Karunasagar, I.; Maiti, B. Nanovaccines to Combat Aeromonas hydrophila Infections in Warm-Water Aquaculture: Opportunities and Challenges. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Species | n | h2 | s.e. |

| Trang et al. (2019a) | White leg shrimp | 15000 | 0.130 | 0.028 |

| Trang et al. (2019b) | White leg shrimp | 120000 | 0.230 | 0.015 |

| Vu et al. (2019) | Striped catfish | 398234 | 0.168 | 0.044 |

| Vu et al. (2023) | Striped catfish | 564 | 0.543 | 0.101 |

| Premachandra et al. (2017) | Yellowtail kingfish | 752 | 0.020 | 0.030 |

| Nguyen et al. (2023) | Yellowtail kingfish | 752 | 0.022 | 0.035 |

| Trait | striped catfish | white shrimp | yellowtail kingfish |

| Survival rate | 0.44 ± 0.09 | -0.17 ± 0.08 | n.a. |

| Growth | 0.52 ± 0.10 | 0.07 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.27 |

| Method | striped catfish | white shrimp* | yellowtail kingfish |

| GBLUP | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.05 |

| Baye R | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.13 | n.a. |

| Machine learning | 0.63 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | n.a |

| Deep learning-MLP | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.17 ± 0.03 |

| Deep learning-CNN | 0.63 ± 0.12 | n.a. | n.a |

| Parameter | Unit | Line | Least Square Mean |

| THC | 10^6cells.mL-1 | High resistance | 7.56 ± 0.73 |

| Low resistance | 7.76 ± 0.92 | ||

| PO | Units.mL-1 haemolymph | High resistance | 0.035 ± 0.006 |

| Low resistance | 0.037 ± 0.006 | ||

| SOD | Units.mL-1 haemolymph | High resistance | 0.378 ± 0.039 |

| Low resistance | 0.354 ± 0.059 | ||

| Lysozyme | Units.mL-1 haemolymph | High resistance | 260.41 ± 4.397 |

| Low resistance | 266.72 ± 6.388 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).