1. Introduction

Quality of life refers to “a person’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns" [

1]. An individual’s quality of life is personal and subjective and differs between individuals due to their values, life circumstances, and socio-cultural factors. Quality of life (QOL) is increasingly being used as a measurable and important health outcome, especially in individuals with chronic diseases with limited life expectancy such as dementia [

2].

Dementia is a chronic, progressive, and usually irreversible deterioration in cognition that is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality [

3]. Globally, the number of people affected by dementia has been increasing during the past several decades, over two-thirds of whom live in low-and middle-income countries, including Vietnam [

4]. Since there is currently no cure for dementia, care services are focused on improving or maintaining QOL in adults with dementia [

5].

A large number of studies have investigated factors associated with QOL but there is no consensus on variables are related to QOL of people with dementia [

5,

6,

7]. The presence of geriatric syndromes and co-incidence of geriatric syndromes is common and may result in worsening of QOL among people with dementia [

8,

9,

10]. However, assessment of geriatric syndromes is often overlooked in studies among this population. Most previous studies only revealed variables such as depressive symptoms, behavioural and psychological disturbance, cognitive functions, and dependence in activities of daily living were most consistently associated with low QOL of people with dementia [

6,

11].

While there is an increasing number of older individuals living in nursing homes with dementia [

12], little is known about their QOL and factors influencing their health-related QOL in older men and women with dementia living in nursing home settings, especially in resource limited countries such as Vietnam. Better understanding of the quality of life among long-stay nursing home residents with dementia is important to kwown what for developing interventions in nursing homes should focus on to improve their quality of life and to their improve disease management. The objectives of this cross-sectional study were to measure health-related QOL and identify factors associated with poor health-related QOL among older adults with dementia living in several nursing homes in Hanoi, Vietnam.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study of older adults with dementia living in three nursing home facilities (Orihome, Nhan Ai, Dien Hong Nursing Center) in Hanoi, Vietnam, from November, 2022 through January, 2023.

In Hanoi, there are presently 20 private nursing homes. Nursing homes included in this study were selected using cluster sampling based on their size: (Small cluster): facility with less than 100 residents; (Medium cluster): facility with 100 to 200 residents; and (Large cluster): facility with more than 200 residents. We then used random sampling to select institutions in each cluster

Target population: older adults with dementia living in nursing homes in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Source population: older adults living in private nursing homes were listed in the Report Market outlook 2021 in Hanoi [

13].

Sampling frame: 11 private nursing home systems were licensed to operate at the time of the study in 2022.

The final study sample consisted of one large cluster (Dien Hong Nursing Center), one medium cluster (Nhan Ai Aged Care Center), and one small cluster nursing home (OriHome Aged Care Center).

2.2. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Long-stay (at least 3 months) residents at the three participating nursing homes were eligible for study consideration if they were 60 years and older and had a diagnosis of dementia according to DSM 5 criteria [

14] as determined by a neuropsychiatrist from the research team at the time of study recruitment.

Participants were excluded from study consideration if they had severe loss of vision, hearing, or were unable to communicate (according to the interRAI Community Health Assessment) [

15], or to answer questions about QOL, were unwilling to participate in the study, or if their family did not consent for them to take part in the study.

2.3. Data collection

The research team consisted of five researchers and two neuropsychiatrists. Prior to recruiting study participants, members of the study team completed a training program on participant screening and study data collection methods.

After initial screening, participants and their family, their nursing home care staff received a complete explanation of the purpose, risks, and procedures of the study. The informed consent of the participants and their family would be obtained if they show interest in participating.

Data were obtained through four approaches: (1) in-person interviews with study participants; (2) examination of the participant including physical tests such as the Timed Up & Go (TUG) test and a 30-second chair stand (30-s CST); (3) interviews with the nursing home care staff, and (4) review of nursing home records. Study participants and nursing home care staff were interviewed separately using a structured questionnaire.

2.3.1. Health-related quality of life

Health-related QOL, the study primary outcome, was assessed using the QOL in Alzheimer’s Disease scale (QOL-AD) through the conduct of in-person interviews [

16]. The QOL-AD consists of 13 items (physical health, energy, mood, living situation, memory, family, marriage, friends, self as a whole, ability to do chores, ability to do things for fun, views of money and life) each of which is rated on a four-point scale as follows: 1 (poor), 2 (fair), 3 (good), and 4 (excellent). The total QOL-AD score was the sum of scores from 13 items which ranged from 13–52 points, with higher scores indicating higher QOL. The internal consistency for the QOL-AD was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. For all 13 items on the scale, the α was 0.77; values above α = 0.70 are considered as evidence of acceptable internal consistency [39]. Resident’s total QOL-AD score was further categorized according to tertiles as: poor QOL (lowest tertile), moderate QOL (middle tertile), and high QOL (highest tertile) based on the distribution of the data, and according to what we considered to be clinically meaningful cut-points of QOL

2.3.2. Other study variables

Nursing home paper records were reviewed by members of the research team for the following data on the long-stay residents: age (classified in 3 group: 60-69 years old, 70-79 years old, 80 years old and over), sex (male, female), marital status (married, divorced/separated, widowed, never married), education level (no formal, primary level, secondary level, college degree or higher), current smoking and drinking, polypharmacy (concurrent use of 5 or more medications [

17]), and comorbidity (defined as the co-occurrence of more than one disease).

Data on resident’s level of cognition was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) through in-person interviews by the research team. It is an 11-question measure that tests five areas of cognitive function: orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language. The maximum MMSE score is 30 points, a lower score being indicative of greater cognitive deterioration [

18]. Physical function was assessed using the TUG and 30-s CST. For the TUG, participants began in a seated position and were instructed to stand, walk 3 meters to a marked area, then return to the starting seated position. The TUG test was performed twice at the participants normal speed and the best time of completion was recorded. A gait aid was allowed for use as needed during the TUG test [

19]. The 30-s CST consists of standing up and sitting down from a chair as many times as possible within 30 seconds. A standard chair without straight back (seat height of 40 cm) was used. Initially, subjects were seated in the middle of the chair with their back in an upright position. Participants were instructed to to rise to a full standing position, then sit back down again at their own preferred speed with their arms folded across their chest. The 30-s CST consists of counting the number of sit-stand-sit cycles completed during the 30 second test [

20], a cutoff score of 11.25 indicates high risk of falls [

21].

Nursing home care staff were interviewed to assess the presence of geriatric syndromes in study participants. These included nutritional status, functional ability, incontinence, sleep disturbance, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Nutritional status was assessed by the Mini Nutritional Assessment Scale-Short Form (MNA-SF), a six-item instrument with scores ranging from 0 to 14 points. A total score of MNA-SF <8, 8–11, and >11 indicates malnutrition, risk of malnutrition, and no malnutrition, respectively. [

22]. Functional ability was assessed using the activities of daily living (ADLs) Barthel index, which measures the extent to which somebody can function independently and has mobility in their ADLs with 5 categories (Independent: 100 points, slight dependency: 91-99 points, moderate dependency: 61-90 points, severe dependency: 21-60 points and total dependency: 0-20 points) [

23]. Presence of incontinence was determined using three Incontinence Questions (3IQ) [

24]. Sleep disturbance was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) which contains 19 questions with a range of 0-21 points. A score greater than 5 demonstrates poor sleep quality [

25].

Dementia-related characteristics such as feeding difficulties, behavioral and psychological symptoms were also assessed by interview the nursing home care staff. Feeding difficulties were assessed using the Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia scale (EdFED) which is an 11-item instrument designed to assess eating and feeding problems in people with late-stage dementia; total scores range from 0 to 20, with 20 being the most serious [

26]. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) questionnaire was used to assess behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), including agitation/aggression (total scores range from 0 to 96), depression (total scores range from 0 to 96), and delusional symptoms (total scores range from 0 to 108). Each behavioral symptom was calculated by its total score (frequency x severity), with higher scores indicating greater severity [

27].

Number of geriatric syndromes was recorded, including polypharmacy, poor sleep quality, malnourished, dependence in ADLs, urinary incontinence, comorbidity, high risk of falls and depression. If a participant had 2 or more geriatric syndromes, he or she was considered to be multimorbidity.

2.4. Data analysis

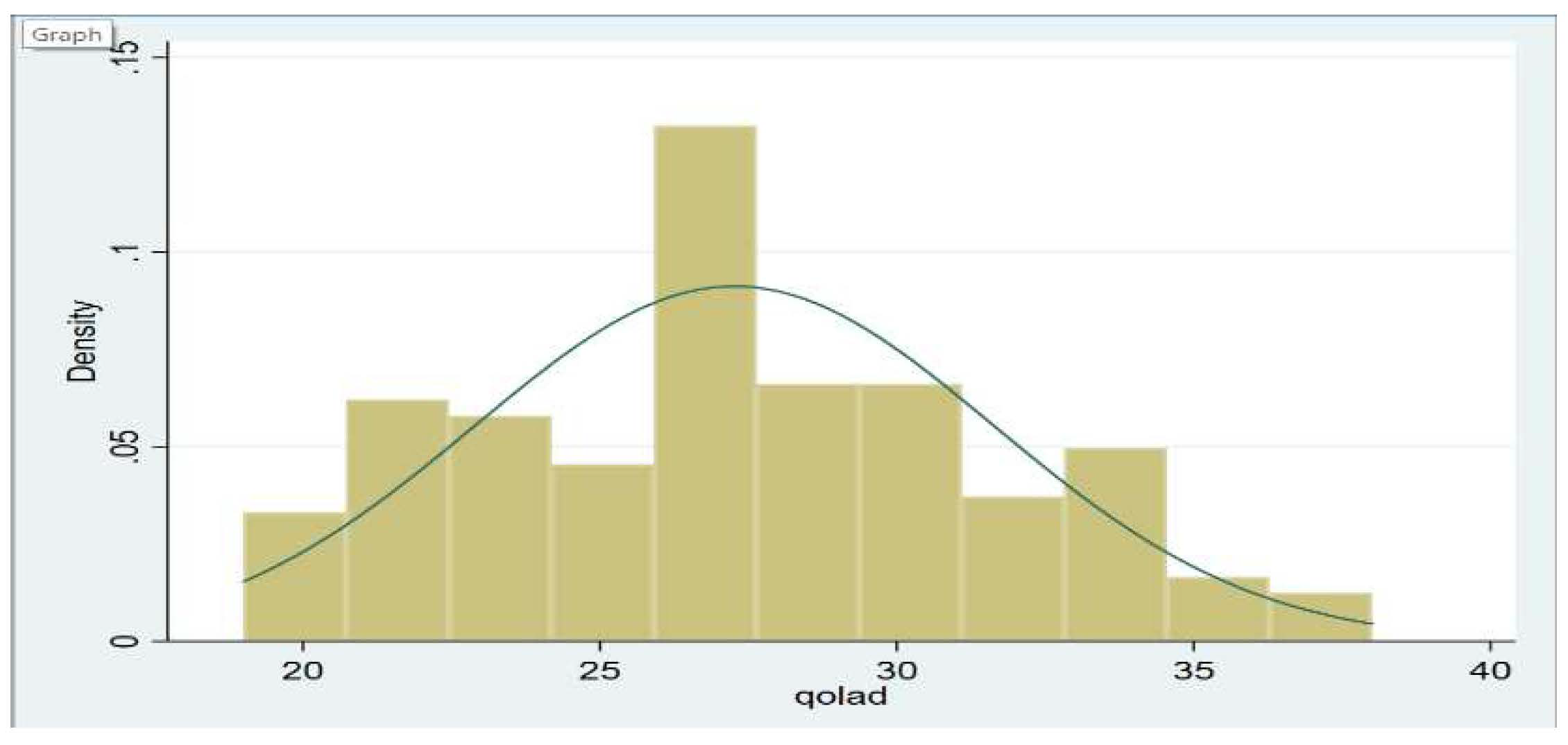

Baseline characteristics were compared between the adults with poor and moderate/high QOL. These data were presented as percentages for categorical variables and as means ± standard deviation for continuous variables. The distribution of the total QOL-AD score was examined and was found to be normally distributed (

Figure 1). We also calculated internal consistency for the QOL-AD by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.70).

Poor health-related QOL was defined among the group with the lowest tertile QOLAD score. Moderate QOL was defined by inclusion in the second tertile of the QOLAD score and those with a high QOL were categorized in the uppermost tertile of the QOLAD score.

We examined several factors associated with poor health-related QOL (vs. moderate/high QOL) in older adults with dementia using univariate and multivariable adjusted logistic regression models. These factors included sociodemographic characteristics, polypharmacy, PSQI score, malnutrition, dependence in Barthel ADLs, TUG test, Edinburgh score, comorbidities, agitation, depression, and delusion scores from the BPSD, 30-s CST test, and the MMSE score. Potential factors associated with the QOL-AD score in the univariate analysis at a threshold of p-value less than 0.20 were entered in our multivariable adjusted logistic regression models. Data analyses were performed using STATA version 17 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

3.1.1. Study Population Characteristics

A total of 140 participants were included. The mean (SD) age of the study sample was 78.3 (+/-8.7) years, 65% were women, half of the participants (51.43%) were widowed. The mean (SD) number of geriatric syndromes per participants was 4.88 (+/-1.22). The prevalence of no formal education among participants was 10,71%.

3.1.2. Health-Related QOL and factors associated with poor QOL

The distribution of health-related QOL is shown in

Figure 1. Study participants had an average QOL-AD total score of 27.3 (SD = 4.4), which ranged from 19 to 38 points. Poor QOL was observed among resident’s ability to do chores, having poor memory, state of physical health, and in their ability to do things for fun. Family, living situation, and mood status were the domains with the highest reported QOL scores, reported as good to excellent. Detailed scores for each item are shown in

Table 2.

In univariate analyses, being malnourished, total dependence in ADLs, urinary incontinence, feeding difficulties, declines in physical function and increased number of geriatric syndromes were associated with poor health-related QOL (lowest tertile group). The most common geriatric syndromes in poor QOL group were being malnourished (78.4%), poor sleep quality (73%), urinary incontinence (56.8%) and total dependence in ADLs (40.5%). The number of geriatric syndromes in the poor QOL group was 5.6(+/-1.1), higher than those in the high/moderate QOL group (4.6 (+/-1.2)). More than 70% of participants in the poor QOL group had five or more geriatric syndromes (

Table 3).

In our multivariable adjusted logistic regression model, poor health-related QOL was associated with malnutrition, total dependence in ADLs, and presence of urinary incontinence (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we investigated the relationship between geriatric syndromes such as malnutrition, total dependence in ADLs, and urinary incontinence and poor health-related QOL among older adults with dementia residing in nursing homes in Vietnam.

Vietnam is one of the fastest-aging countries in the world with an increasing number of older individuals with dementia [

28]. Policy makers are attempting to build health care models to improve the QOL for these individuals [

28]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining health-related QOL among men and women 60 years and older with dementia living in nursing homes in Vietnam. We found that nursing home residents had, on average, a moderate level of QOL.

The average QOL-AD scores reported in our study were lower compared with previous findings in nursing home residents with dementia living in industrialized countries who used similar study questionnaires [

5,

29,

30]. For example, a study in 8 European countries showed that average QOL-AD total score was 32.5 (SD =6.3) [

5]. These differences can likely be explained by the fact that these earlier studies were conducted in industrialized countries that have different social care systems, healthcare organizations, cultural norms, policy frameworks, attitudes toward nursing home placement, and family involvement in residents’ care [

5]. Notably, in Vietnam, individuals with dementia often stay at home and are only placed in nursing home facilities when their cognitive impairment is severe and their caring needs exceed the capacity of their families. The lower average QOL in this study population may also reflect the fact that residents in other countries enter nursing homes at earlier stages of their disease.

We observed that a high proportion of participants reported lower QOL in domains related to their physical health, ability to do chores and things for fun, and with their poor memory. While many studies have used proxies to report QOL among individuals with dementia [

7,

31], we asked nursing home residents to self-report their QOL. This approach was taken because individuals with dementia and their caregivers may not perceive QOL in the same way [

32] and we sought to identify those aspects of living that are most meaningful to individuals with dementia. Our findings suggest that interventions focusing on physical, social, and cognitive domains should be implemented and evaluated for their effectiveness in enhancing the QOL of individuals with dementia living in nursing homes in Vietnam.

Our results confirmed a high prevalence of multimorbidity among older adults with dementia. All participants were reported having at least two geriatric syndromes. The number of geriatric syndromes in the poor QOL group was higher than those in the high/moderate QOL group. Our research findings show the support for evidence from previous studies that the presence and co-incidence of geriatric syndromes were highly prevalent among older adults with dementia [

8,

9,

10]. A geriatric assessment is often overlooked in many studies among older adults with dementia due to cognitive impairment make the assessment more difficult and complicated [

33]. Our study revealed that the geriatric assessment can be applied to older people with dementia in nursing homes and the assistance of the caregiver played an important role in the geriatric assessment process. Previous studies showed that older adults with multimorbidity are at greater risk for worse adverse outcomes [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. They may have functional impairment, poorer QOL and overall health status [

37,

38]. Furthermore, they experience greater health services use such as longer lengths of stay when hospitalized, more frequent inpatient hospitalizations and increased emergency admissions [

36,

37]. A geriatric assessment should be identified early to develop effective strategies for identifying patients with multiple conditions and initiating prompt prevention and intervention strategies.

Our cross-sectional epidemiological study examined the association between health-related QOL in older individuals with dementia and modifiable risk factors such as the geriatric syndromes. We found malnutrition, total dependence in activities of daily living, and the presence of urinary incontinence were associated with poor QOL. These findings underscore the importance of conducting a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which encompasses domains including urinary continence, physical function, and nutrition, since it enables the identification of potential problems and facilitates the implementation of various interventions approaches to enhance nursing home residents overall health-related QOL.

4.1. Study strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate health-related QOL among older individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes in Vietnam. Our findings have important implications for the type of clinical services required for the care of these older adults. The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, however,due, in part, to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies. Our study sample size was relatively modest, and participants in this study were recruited from nursing homes, potentially limiting their representativeness to older community dwelling residents.

5. Conclusions

Older individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes in Hanoi, Vietnam generally have a moderate QOL, which is lower than that observed in industrialized countries. Key challenges include their less than optimal physical health, ability to perform chores, their poor memory, and need for engagement in enjoyable activities. We recommend interventions targeting these areas to enhance the health-related QOL for this population. Additionally, addressing modifiable risk factors such as malnutrition, activities of daily living, and urinary incontinence through comprehensive geriatric assessment and management is crucial for improving their overall QOL.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute of Health (award number: 5D43TW011394-02) for financial support of publication. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01AG064688 (Hinton/Nguyen MPI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanoi Medical University (IRB00003121).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Board of Directors and medical staff at the Dien Hong Nursing Center, Nhan Ai Aged Care Center and OriHome Aged Care Center in Hanoi, Vietnam. We would like to thank all of the participants in our study, who generously shared their time, experiences, and insights with us. The authors gratefully appreciate Ms Le Thu Vu Pham, Ms Thu Thi Pham and Mr Huy Quang Lai for helping to recruit patients for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

-

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med, 1998. 46(12): p. 1569-85.

- Megari, K., Quality of Life in Chronic Disease Patients. Health Psychol Res, 2013. 1(3): p. e27.

- Duong, S., T. Patel, and F. Chang, Dementia: What pharmacists need to know. Can Pharm J (Ott), 2017. 150(2): p. 118-129.

- Mattap, S.M., et al., The economic burden of dementia in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health, 2022. 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Beerens, H.C., et al., Quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia receiving long term institutional care or professional home care: the European RightTimePlaceCare study. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014. 15(1): p. 54-61. [CrossRef]

- Beerens, H.C., et al., Factors associated with quality of life of people with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud, 2013. 50(9): p. 1259-70. [CrossRef]

- Burks, H.B., et al., Quality of Life Assessment in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2021. 50(2): p. 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Gan, J., et al., The presence and co-incidence of geriatric syndromes in older patients with mild-moderate Lewy body dementia. BMC Neurology, 2022. 22(1): p. 355. [CrossRef]

- Namioka, N., et al., Comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2015. 15(1): p. 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, M.J.R., et al., Comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly outpatients with dementia. Dement Neuropsychol, 2007. 1(3): p. 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Akpınar Söylemez, B., et al., Quality of life and factors affecting it in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2020. 18(1): p. 304.

- Prins, M., et al., Nursing home care for people with dementia: Update of the design of the Living Arrangements for people with Dementia (LAD)-study. J Adv Nurs, 2019. 75(12): p. 3792-3804. [CrossRef]

- UNFPA, Market outlook for elderly care service in Vietnam. November 2021.

- Hugo, J. and M. Ganguli, Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med, 2014. 30(3): p. 421-42.

- Urqueta Alfaro, A., et al., Detection of vision and /or hearing loss using the interRAI Community Health Assessment aligns well with common behavioral vision/hearing measurements. PLoS One, 2019. 14(10): p. e0223123.

- Kahle-Wrobleski, K., et al., Assessing quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: Implications for clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 2017. 6: p. 82-90.

- Varghese, D., C. Ishida, and H. Haseer Koya, Polypharmacy, in StatPearls. 2023, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL).

- Mitchell, A.J. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): Update on Its Diagnostic Accuracy and Clinical Utility for Cognitive Disorders. 2017.

- Kear, B.M., T.P. Guck, and A.L. McGaha, Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: Normative Reference Values for Ages 20 to 59 Years and Relationships With Physical and Mental Health Risk Factors. J Prim Care Community Health, 2017. 8(1): p. 9-13.

- Jones, C.J., R.E. Rikli, and W.C. Beam, A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport, 1999. 70(2): p. 113-9. [CrossRef]

- Roongbenjawan, N. and A. Siriphorn, Accuracy of modified 30-s chair-stand test for predicting falls in older adults. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 2020. 63(4): p. 309-315. [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein LZ, H.J., Salvà A, et al, Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci, 2001. 56(6).

- Mahoney F, B.D., Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J, 1965. 14: p. 61-5.

- Lam, A., Advancing your practice: Urinary incontinence. AJP: The Australian Journal of Pharmacy, 2021. 102(1202): p. 62-66.

- Buysse, D.J., et al., The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 1989. 28(2): p. 193-213. [CrossRef]

- Watson, R., J. MacDonald, and T. McReady, The Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia Scale #2 (EdFED #2): inter- and intra-rater reliability. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 2001. 5(4): p. 184-186. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L., et al., The Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia, 1994. 44(12): p. 2308-2308.

- Nguyen, T.A., et al., Towards the development of Vietnam's national dementia plan-the first step of action. Australas J Ageing, 2020. 39(2): p. 137-141. [CrossRef]

- Akpınar Söylemez, B., et al., Quality of life and factors affecting it in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2020. 18(1): p. 304. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, B., et al., Quality of care and quality of life of people with dementia living at green care farms: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr, 2017. 17(1): p. 155.

- Griffiths, A.W., et al., Exploring self-report and proxy-report quality-of-life measures for people living with dementia in care homes. Qual Life Res, 2020. 29(2): p. 463-472. [CrossRef]

- Hoe, J., et al., Quality of life of people with dementia in residential care homes. Br J Psychiatry, 2006. 188: p. 460-4. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D., et al., Best paper of the 1980s: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: geriatric assessment methods for clinical decision-making. 1988. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2003. 51(10): p. 1490-4. [CrossRef]

- You, L., et al., Association between multimorbidity and falls and fear of falling among older adults in eastern China: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health, 2023. 11: p. 1146899. [CrossRef]

- Kadambi, S., M. Abdallah, and K.P. Loh, Multimorbidity, Function, and Cognition in Aging. Clin Geriatr Med, 2020. 36(4): p. 569-584.

- Rodrigues, L.P., et al., Multimorbidity patterns and hospitalisation occurrence in adults and older adults aged 50 years or over. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 11643. [CrossRef]

- Palladino, R., et al., Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilisation and health status: evidence from 16 European countries. Age and Ageing, 2016. 45(3): p. 431-435. [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O., et al., Chronic physical conditions, physical multimorbidity, and quality of life among adults aged ≥ 50 years from six low- and middle-income countries. Quality of Life Research, 2023. 32(4): p. 1031-1041.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).