1. Introduction

The placenta is a temporary organ initiating from the trophoblast following embryo implantation, whose function is essential for further fetal development and growth. Morphologically, it is generally round or oval shaped, measures around 22 centimeters in diameter and is composed of both maternal and embryonic tissue [

1].

Since placentogenesis it is a complex process, placentas vary in shape, location, size, and functional capacities, leading to several potential abnormal placental variants. Although the incidence of such anomalies ranges between 2-4%, the rate of obstetric complications in these patients is relatively high, with increased fetal morbidity and mortality. Because placental anomalies have a low incidence, their diagnosis is more often established after delivery, in the third stage of labor, when complications appear.

Morphologic placental anomalies can be classified as: circumvallate placenta, succenturiate placenta, multilobed placenta (bilobed/bipartite/duplex placenta), placenta fenestrata, placenta membranacea, and ring-shaped placenta [

2].

The succenturiate placenta is a morphological variation of the placenta that usually presents as a distinct lobe from the main placental disc, which can be single or multiple. It occurs in approximately 0.16% to 5% of pregnancies [

3,

4]. According to some authors the incidence of succenturiate placenta is favored by pelvic infections, preeclampsia, infertility and the use of assisted reproductive techniques [

5].

Suppling vessels connecting satellite placental lobes to the main placental disk are surrounded only by communicating membranes, comporting a high risk of vascular accidents. It is crucial to establish the location of connecting vessels and especially to look for any vascular connection crossing the internal cervical ostium (vasa praevia).

Abnormal insertion of the umbilical cord is also a characteristic of this pathology with velamentous insertion diagnosed in almost 50% of cases [

3]. The most common complications of succenturiate placentas include fetal and maternal death resulting from ruptured accessory vessels during uterine contractions causing hemorrhage and abruptio placentae, prematurity in the context of emergency caesarean section for acute fetal distress [

6], placental retention in the third stage of delivery and postpartum hemorrhage [

2].

To ensure maternal-fetal safety and anticipate possible hemorrhagic complications that can threaten the life of the patient and fetus it is crucial to make the correct antenatal diagnosis of vasa previa and to raise suspicion of a succenturiate lobe placenta. However, the prenatal ultrasound detection of this placental anomaly is not always handy. When ultrasound evaluation is insufficient or confusing, placental evaluation by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is a safe and effective tool to refine diagnosis [

7].

Aiming to illustrate the potential morbidity of the succenturiate placenta we present the case of a patient correctly diagnosed with this type of placental anomaly at 24 weeks of pregnancy who presented to the emergency department with hemorrhage and abruptio placentae at 33 weeks of pregnancy.

2. Case Presentation

This is the case of a 27-year-old pregnant female patient, with unremarkable general, gynaecologic and obstetric history (menarche 13 years, regular menses - rhythm 28X5 days, without dysmenorrhea, 1 spontaneous abortion at 11 weeks of pregnancy) who presented for vaginal bleeding at 33 WG (weeks of gestation).

Current pregnancy history included a low risk first trimester genetic screening for Down syndrome by the integrated test, negative infectious screening and normal routine lab work-up. At the 20WG morphology scan the suspicion of VSD (ventricular septal defect) with normal outflow tracts was raised, which prompted the recommendation for re-evaluation at 26WG.

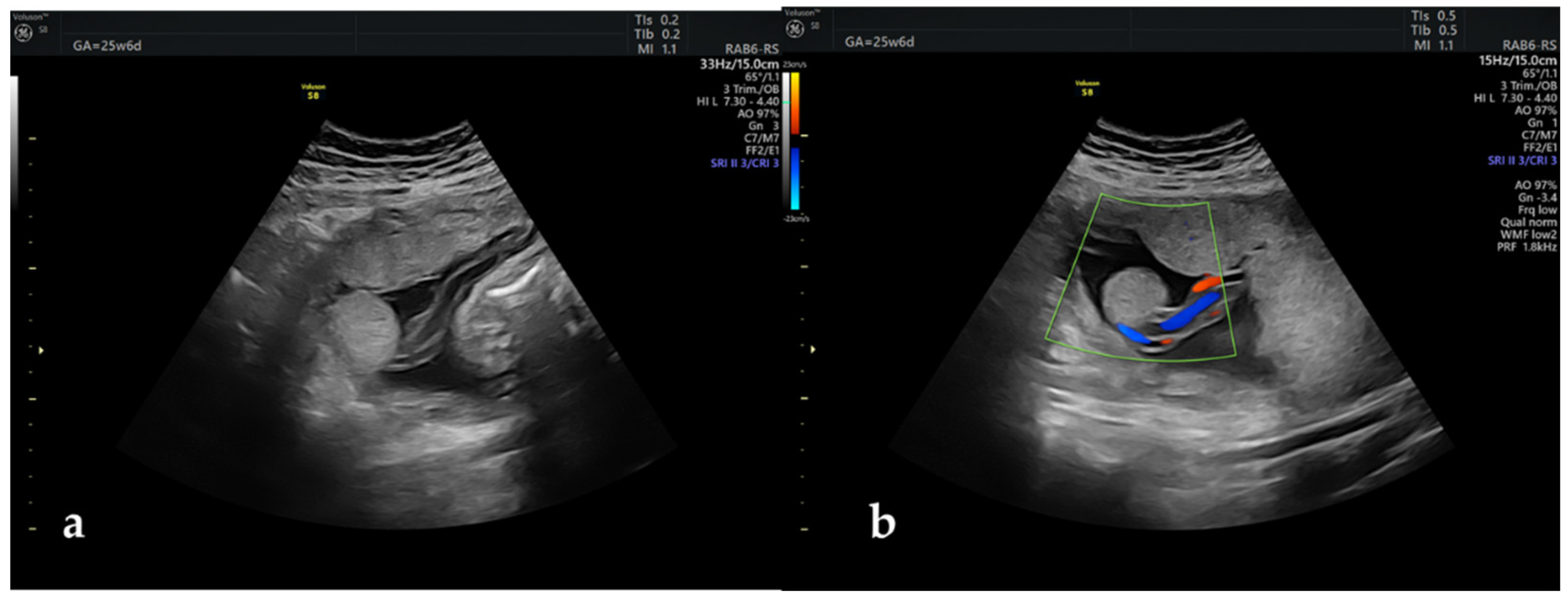

The repeat scan infirmed the VSD but raised the suspicion of an aberrant placental lobe located towards the left uterine flank, distant from the main placental mass (

Figure 1). Doppler examination depicted the presence of umbilical vessels near the aberrant placental lobe, without being able to certify a vascularly connection with the main placental disk. No other placental abnormalities were identified during the ultrasound examination, the umbilical cord inserting centrally at the level of the main placental mass. Even though the location of the accessory lobe and supplying vessels were fundal, screening for vasa praevia was performed by vaginal ultrasound and this anomaly was excluded.

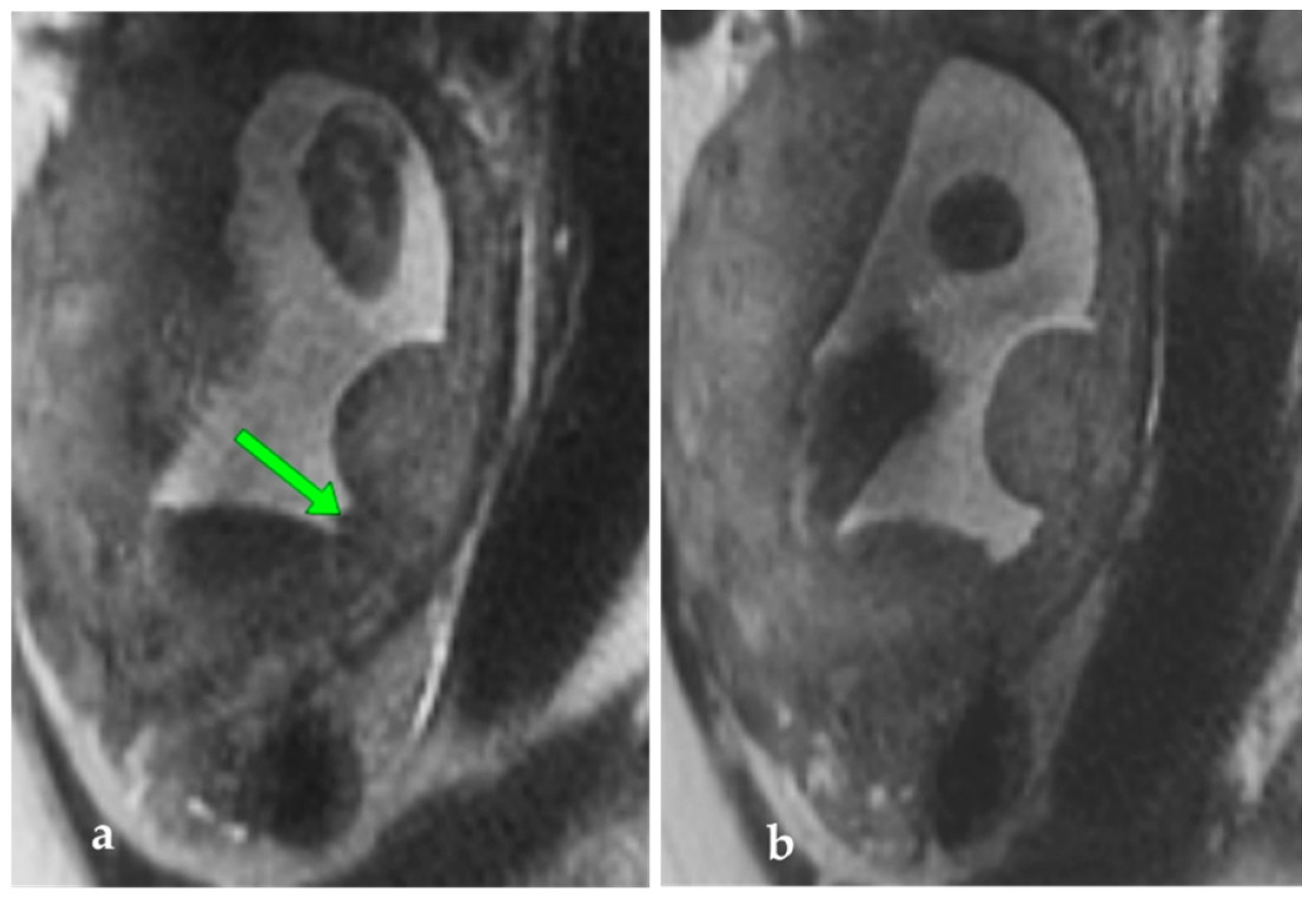

To rule out the presence of other placental satellites and to clarify the relationship between the umbilical vessels and the lobe, MRI was performed at 28 WG. MRI examination confirmed the presence of the abnormal placental lobe measuring 36.5/19/35 mm, connected by a narrow band of tissue to the rest of the placental parenchyma, possibly placental vessels (

Figure 2). The diagnosis of succenturiate placenta was thus confirmed, without other placental abnormalities, and a normal insertion of the umbilical cord.

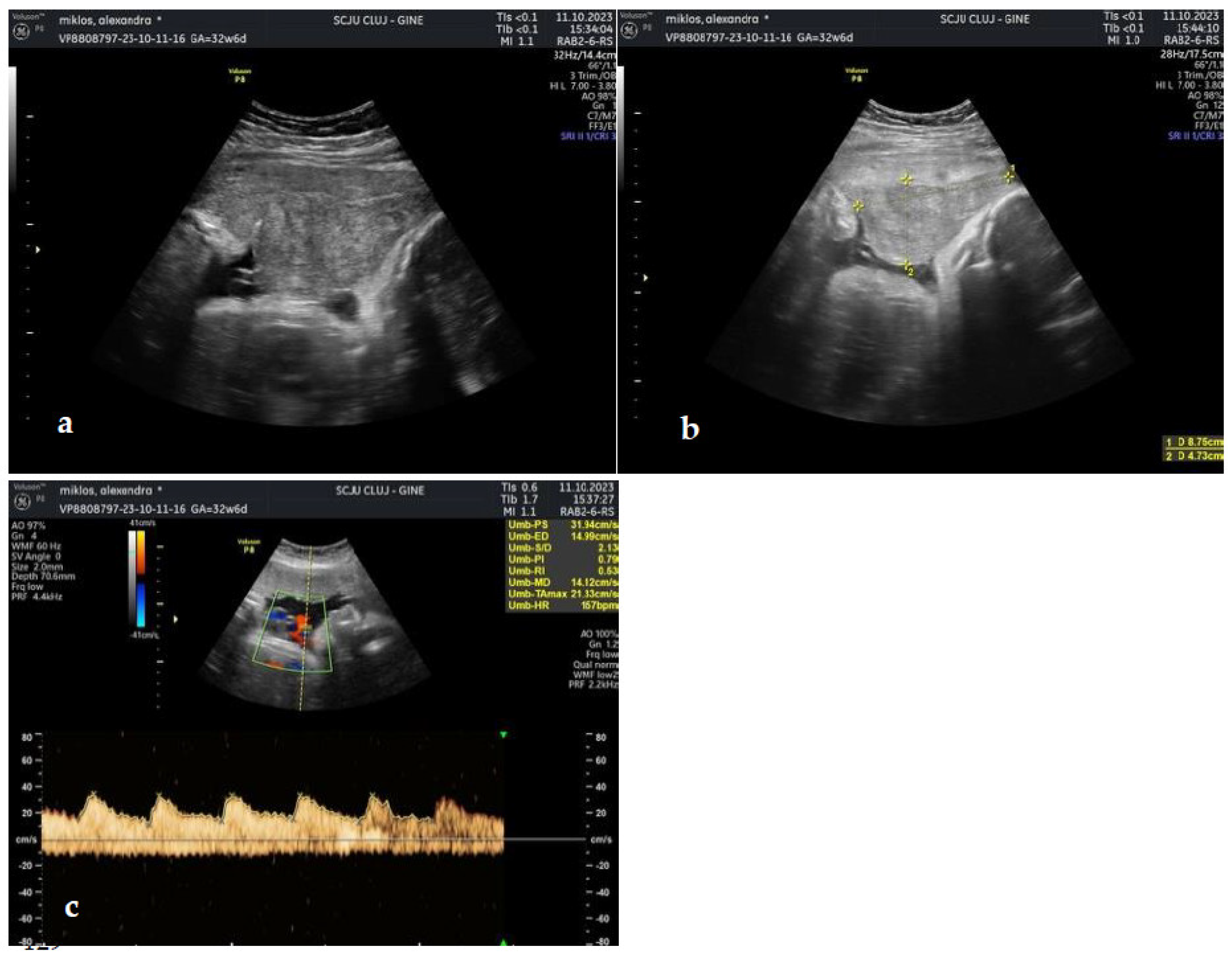

The patient presented to the emergency room at 33 WG with moderate vaginal bleeding, which had initiated approximately 40 minutes prior to arrival, without uterine contractility and normal fetal movements. The clinical examination confirmed moderate vaginal bleeding, without cervical changes. The patient was normotensive (no history of hypertension during pregnancy), with mild tachycardia. Ultrasound scanning identified a retroplacental hematoma of approximately 9/5 cm with normal fetal heart rate, and normal Doppler indices (

Figure 3).

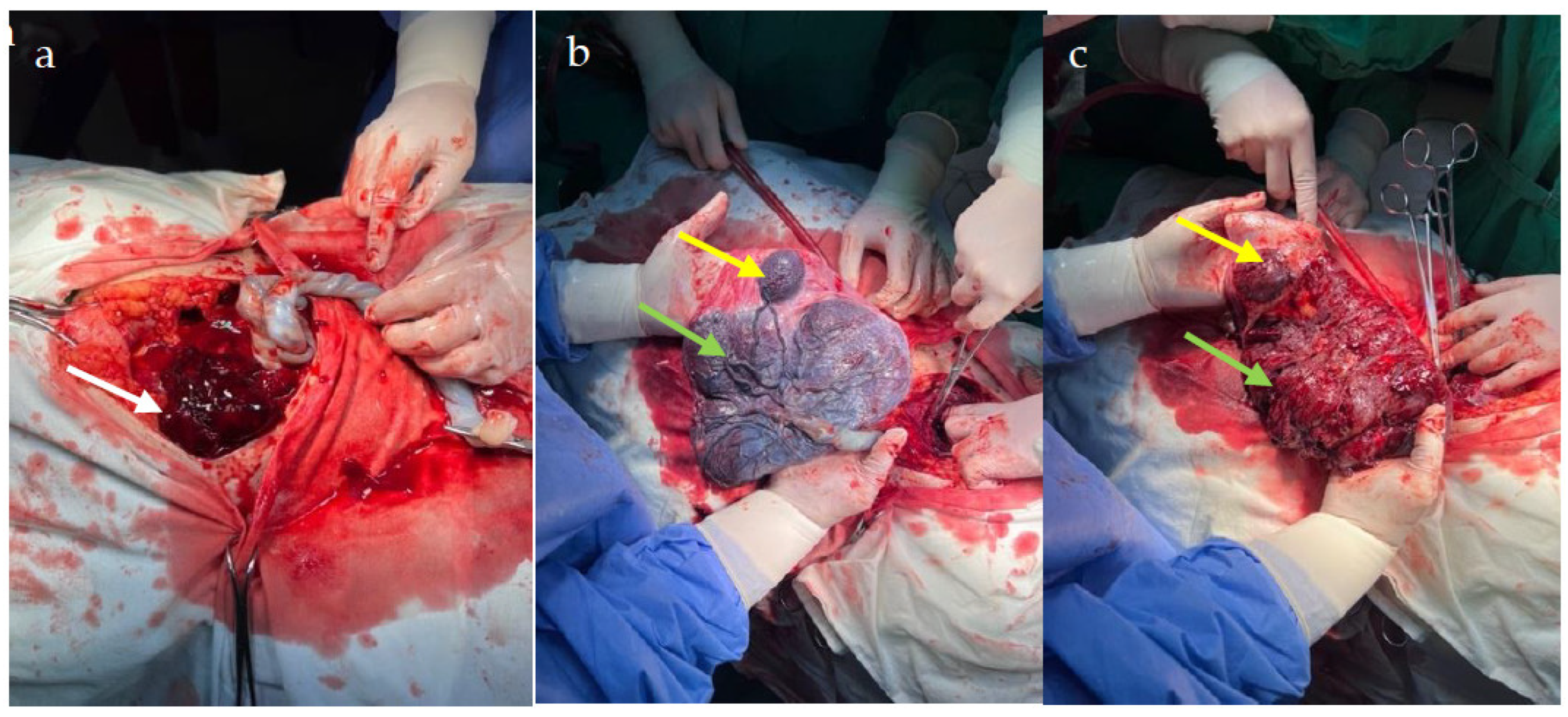

An emergency caesarean section was performed, delivering a male fetus, weighing 2250g, with a 1 and respectively 5 minutes Apgar score of 5/7. Emergency lab tests picked up only mild anemia (Hb = 10.1mg/dl, Ht = 32.7%). In the context of prematurity, neonatal hospital stay was 9 days, with the first 2 days spent in the NICU (neonatal intensive care unit). Intraoperatively, the retroplacental hematoma was highlighted, as well as the aberrant placental lobe and adjacent vessels (

Figure 4). When examining the placenta, the vascular connection between the aberrant placental lobe and the main placental mass was observed, the hematoma having accumulated between the lobe and the rest of the placental mass (

Figure 4).

The rest of the hospital stay was uneventful, the patient was discharged together with the newborn on the 13th postoperative day.

3. Discussion

Placental anomalies are rare and given they frequently occur without any identifiable risk factors often go undiagnosed. The accuracy of prenatal diagnosis is important both for the management of labour and for preventing maternal and fetal complications.

Along with the technological advances in the field of ultrasound, the use of 3D ultrasound and volumetric acquisitions, the detection rate of the succenturiate placenta and other placental abnormalities has increased, but only for patients at high risk for these pathologies [

8].

Although the data in the medical literature regarding succenturiate placenta is limited especially to case reports, there are a few studies debating about the possible complications of this pathology.

In a study published by Ma et al. in 2016, the authors reported that the succenturiate

placenta is related to a higher incidence of preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, increased risk of prematurity, premature abruption of normally inserted placenta and caesarean delivery [

5]. Other later studies have confirmed the results of Ma et al, concluding that low birth weight, perinatal death, premature birth, and emergency caesarean are the main complications associated with this pathology [

9,

10].

Regarding placental abruption, Kumari et al. reported a low risk in succenturiate placentas, with such complication is not commonly reported in the literature [

11].

This data was also confirmed in a recent review from early 2023, were the authors concluded that succenturiate placenta may be a high-risk factor for emergent caesarean delivery and postpartum haemorrhage, whereas it may not be a risk factor for preterm birth, fetal growth restriction or placental abruption [

2].

However, in our case, the patient presented to emergency room with abruptio placentae, in the absence of other risk factors such as preeclampsia, physical/psychological trauma or consumption of prohibited substances, with the placental anomaly as the only potential culprit. The histopathological report confirmed the rupture of placental vessels neighbouring the aberrant placental lobe with the extension of the hematoma towards the main placental mass and its detachment.

Abnormal insertion of the umbilical cord is also common in these placental pathologies, most often velamentous cord [

3]. In our case, the insertion of the umbilical cord was normal, which was probably a determinant factor for the good prognosis of the fetus.

MRI is a handy and safe imaging means of refining the diagnosis of placental pathologies [

12]. It seems to have a higher accuracy in detecting placental anomalies compared to ultrasound, especially in advanced pregnancies with placentas located on the posterior wall of the uterus [

13]. MRI seems to provide better assessment of myometrial infiltration in the placenta accreta spectrum and is more efficient in identifying placental hematomas due to the easier identification of blood degradation products [

12,

13,

14]. MRI can thus provide additional information regarding placenta anomalies, information that will contribute to improving the fetal and maternal prognosis.

4. Conclusions

Prenatal ultrasound studies must also focus on the identification of placental anomalies with MRI being a safe and effective tool to certify diagnosis. Timely detection of placental variations ensures proper follow-up and improved fetal and maternal prognosis in case of complications. In the case of our patient the correct prenatal diagnosis of succenturiate placenta allowed for awareness to complications and effective diagnosis and management of abruption with good fetal and maternal outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing – original draft preparation, IGG; methodology, GN, GC, DM, IR; data curation, AS, AP, MS.; writing—review and editing, GN, CG.; supervision, GC, DM, IR.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to submission of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rathbun KM, Hildebrand JP. Placenta Abnormalities; Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Matsuzaki, S.; Ueda, Y.; Matsuzaki, S.; Sakaguchi, H.; Kakuda, M.; Lee, M.; Takemoto, Y.; Hayashida, H.; Maeda, M.; Kakubari, R.; et al. Relationship between Abnormal Placenta and Obstetric Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaliere, A.F.; Rosati, P.; Ciliberti, P.; Buongiorno, S.; Guariglia, L.; Scambia, G.; Tintoni, M. Succenturiate lobe of placenta with vessel anomaly: a case report of prenatal diagnosis and literature review. Clin. Imaging 2014, 38, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Igarashi, M. Clinical significance of pregnancies with succenturiate lobes of placenta. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008, 277, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-S.; Mei, X.; Meia, X.; Niu, Y.-X.; Li, Q.-G.; Jiang, X.-F. Risk Factors and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes of Succenturiate Placenta: A Case-Control Study. J. Reprod. Med. 2016, 61, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Ueda, Y.; Matsuzaki, S.; Kakuda, M.; Lee, M.; Takemoto, Y.; Hayashida, H.; Maeda, M.; Kakubari, R.; Hisa, T.; et al. The Characteristics and Obstetric Outcomes of Type II Vasa Previa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruciat, G.; Nemeti, G.I.; Popa-Stanila, R.; Florian, A.; Goidescu, I.G. Imaging diagnosis and legal implications of brain injury in survivors following single intrauterine fetal demise from monochorionic twins – a review of the literature. J. Perinat. Med. 2021, 49, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro Rezende G, Araujo Júnior E. Prenatal diagnosis of placenta and umbilical cord pathologies by three-dimensional ultrasound: pictorial essay. Med Ultrason. 2015, 17, 545–549. [Google Scholar]

- Nkwabong, E.; Njikam, F.; Kalla, G. Outcome of pregnancies with marginal umbilical cord insertion. J Matern Neonatal. 2021, 34, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragie, H.; Oumer, M. Marginal cord insertion among singleton births at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Biswas, A.K.; Giri, G. Succenturiate placenta: An incidental finding. J. Case Rep. Images Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 1, 1–4, Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:70796284 (accessed on). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, H.; Hanaoka, M.; Dawkins, A.; Khurana, A. Review of MRI imaging for placenta accreta spectrum: Pathophysiologic insights, imaging signs, and recent developments. Placenta 2020, 104, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mervak BM, Altun E, McGinty KA, Hyslop WB, Semelka RC, Burke LM. MRI in pregnancy: Indications and practical considerations. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019, 49, 621–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadl, S.A.; Linnau, K.F.; Dighe, M.K. Placental abruption and hemorrhage-review of imaging appearance. Emerg. Radiol. 2019, 26, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).