1. Introduction

Culture is dynamic; it always changes [

1]. Sometimes people cannot accept this phenomenon that culture is moving. Furthermore, the thinking of landscape shapes culture, and on the contrary, culture also shapes landscape. This is a critical discussion. The idea that nature and culture are not related is the subject of crucial discussion among cultural experts because natural landscapes shape how humans carry out activities, and in reverse, how humans do their activities shapes landscapes. Humans are not just doing physical activity in a place; they also think and arrange their social lives based on the conditions in which they live. Thus, somehow, the landscape in which humans live, think, engage in activities, and interact with each other is still influenced by the stretch and contour of the location where they live. This statement shows that humans' geographical setting has social and cultural dimensions, not just an empty place. Nevertheless, humans can also shape their environment deliberately or unconsciously.

In the case of Lake Limboto, we observed that from time to time the activities of people surround the lake have been fluctuating depending on the lake’s circumstances. Most of the people around the lake are no longer depending on fishing as their main occupation because the condition of the lake is increasingly shrinking. However, when they have other jobs, they still occasionally go fishing on the lake, even though they know they would not get much.

The current condition of Lake Limboto is not as picturesque as in the historical documents of the Dutch and in the oral stories of the people of Gorontalo. Over the course of several centuries, the lake has seen significant transformations. Nowadays, people around the lake are confronted with numerous problems because of the condition of the lake. The alteration of environmental circumstances has resulted in the activities of the people in the Lake Limboto environment. Their occupation is also changing from their previous patterns. In the past, the majority of males in that particular region were engaged in the occupation of fishing. Gradually, they have been transitioning their occupations to various sectors, including agriculture and transportation, such as farmers and bentor (local public transportation) drivers, or other occupation that they can do for living. Currently, the condition of the lake is getting more critical; even geologists and environmentalists have indicated the lake will disappear around 2025–2030 [

2].

Based on the above problems, we comprehend that the people living in the lake area confront multiple problems, including environmental problems and sociocultural problems. The main thing is that socio-cultural problems evolve in line with the changing condition of the lake or vice versa. Therefore, the questions in this research are: how have the people in Limboto Lake maintained their lives so far? This article aims to expose how the people in the lake have maintained their lives so far based on on-site observations and also supported by historical documents, oral stories, and the socio-cultural practices of the local community residing near the lake. Additionally, this study seeks to assess the reactions of the surrounding communities to this specific occurrence. This research is expected to provide information on how the people around the lake have anticipated the increasingly critical lake conditions, how they survive, and how resilient they are to form and improving their living conditions. Also, this research is expected to become an academic paper that records the activities of the people around the critical Lake Limboto.

2. Literature Review

Lake Limboto is regarded as one of the lakes that is considered to be in the most critical condition in Indonesia [

3]. The cause of this shallowing is very intricated, making it difficult to find the root of the problem. This shallowing is a result of lake sedimentation coming from rivers as well as sedimentation caused by humans’ activity patterns in the lake [

4]. In this context, it is evident that the reduction in the depth of the lake is attributable not just to natural processes but also to human interactions with the environment. These two things are interrelated, resulting in complex problems.

Various factors associated with natural phenomena might contribute to the shallowing of the lake, such as sedimentation and rainfall, among others [

5,

6]. Apart from that, other factors related to human activities contribute to the shallowing of the lake, such as cultivation efforts and tree cutting activities from forests in the upper reaches of the Limboto watershed, meanwhile this forest is supposed to act as an area of water catchment [

7]. Local people's activities around the lake relate to the longstanding practice of shifting farming. As a result, environmental degradation occurs providing direct impacts on the waters of Lake Limboto, such as shallowing and eutrophication as a result of increasing nutrients of the disposal of fish feed from aquaculture activities were thrown into the lake, water hyacinth, etc. [

4] and pollutants into the lake's water body. Accordingly, it is concluded that the waters in Lake Limboto have been polluted to several levels, although heavy metal pollution is still within normal limits [

8]. This condition is worrying for the sustainability of the lake and fish production from the lake, because the fish is traded to the public. Besides, the part of the lake that had dried up is used as a residential area [

3].

At the same time, socio-cultural research about humans’ activities around the lake was also carried out by socio-cultural researchers, who tried to unravel the complexity of the problems that caused the lake to become increasingly shallow. According to Hasim [

9], one matter that contribute to this complexity is the regulations of government policy about natural and environment resource management. The spatial planning of the lake area in particular and the region in general often ignores aspects of the principle of harmony of spatial functions.

Junus and Mamu [

3] have the same conclusion with Hasim that spatial planning policies, especially in the lake area is still weak. Also, the management network of adaptive governance in Lake Limboto is still weak [

10]. Illegal residential development on the banks of the lake automatically results in the lake ecosystem. The large number of residential buildings filled the areas alongside of the lake are generally permanent and semi-permanent. The problem is the population grows rapidly, the need for land is growing based on community expectations. The growing population will definitely increase the importance of the position of land ownership rights, especially the dried-up land along lake shores.

Sarson [

11] who conducted research from Law studies explained that Lake Limboto area is an open area. Since the area of Lake Limboto is open, it has experienced a process of exploitation continuously even tends to be excessive, and the exploitation does not pay attention to aspects of its preservation. As a result of the silting of Lake Limboto, most of the areas turned into lake settlements or converted into agricultural businesses. By the national land law, arising land due to the shallowing (

aanslibbing) is a directly controlled land by the State, therefore everyone who will control the arising land (

aanslibbing) must obtain prior permission from the government authority, namely the National Land Agency. Nevertheless, the people who lived and built settlement on the lake bank had no permission from the government. This is due to the fact that the land has been used as a dwelling place since the 1980s. They controlled the land generation to generation.

From the various studies above, both in the natural sciences and socio-cultural sciences, we can understand the complexity of the problems in Lake Limboto. The problem of lake shallowing goes hand in hand with socio-cultural problems. On the socio-cultural side, we observed that the majority of people who live on the edge of the lake are trying to survive themselves so that their lives will always continue. They stand to live on the edge of the lake because this area is productive, fertile, and free, and there are no other places to move in. However, most of them do not realize the consequences if this place they depend on disappears. Accordingly, this research about how people around the lake have been trying to survive in poor circumstances is done.

2.1. Cultural Studies

In the context of this study, the people of Lake Limboto experienced two pressing conditions; natural deterioration, threatened of socio-economic and cultural circumstances. The local condition is a critical lake so that most of the people around the lake can no longer carry out lake fishing activities, because many species of lake fish have become extinct, and furthermore the land surround the former lake dries up. This is a threat for their lives and culture.

This study is an interdisciplinary framework with emphasizing on culture studies. Cultural studies basically observe and criticize cultural movements that cannot be separated from historical, social, political and economic contexts [

12]. However, cultural studies also study cultural geography where culture and geography have connections. In this case the geography where humans live, has a large impact on human activities that shape their culture [

13]. Research with a framework of cultural studies is needed to examine phenomena related to issues of place and humans. Nevertheless, cultural studies examine culture related to power [

14]. Cultural studies believe that culture moves not in a vacuum, there is power that makes culture move and develop which is inseparable from the historical, social, political and economic context. Power in this case is not always the government that has the power politically to regulate, but it can also be in the form of ideology that can drive culture [

12,

13,

15]. Cultural studies also examine cultural geography. Cultural geography concerns with humans and nature within particular of regions over long periods of time [

13]. The symptoms in the last few decades, climate change is very fast and natural damage resulting in natural disasters can change the order of human life, but also humans’ activities change towards their needs resulting in changing natural environment. This also shape culture geography. Therefore, culture moving and developing are not only inseparable from the historical, social, political and economic context, but also place or geography.

3. Research Method

3.1. In-Dept Interviews

The collection of the research data was used through in-depth interviews, and other supporting sources like old documents, oral stories to support the interpretation and argumentation on the field data, namely in the form of history and journal articles about the lake. In-depth interviews are needed to get an overview and understanding of how the community is trying to survive in a critical lake condition, and how the community's resilience is in dealing with the poor circumstances. The interviewed people were main informants, namely the sub-district or village government, and the people around the lake. The interviewed respondents were around 102 people from all the villages that were traced.

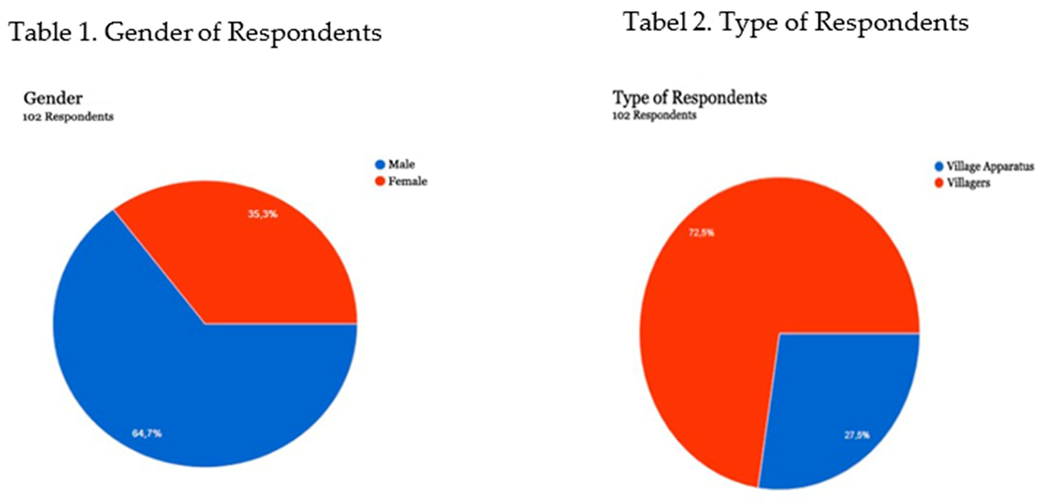

3.2. Tables and Figures

Despite the fact that this study also makes use of tables and figures, they only serve to clarify the data that the field research's findings provide. The goal of this study is to find out how the residents of Lake Limboto have managed to survive all this time and what preparations they have made for the eventual loss of Lake Limboto. Tracing the way of life of the community and how to deal with disasters are very important. For that, the search will involve many parties in interviews, both the community around the lake and the government at the sub-district and village levels.

Interviews were conducted with 102 informants in 27 sub-districts and villages to find out the fluctuation activities of the people so that they can survive and be resilient due to the circumstances of the lake, which is getting narrower and shallower. The change of seasons is uncertain, which often results in disasters such as floods, or if the summer is very long, which results in drought, the people around Lake Limboto take alternative jobs and activities to survive based on their conditions.

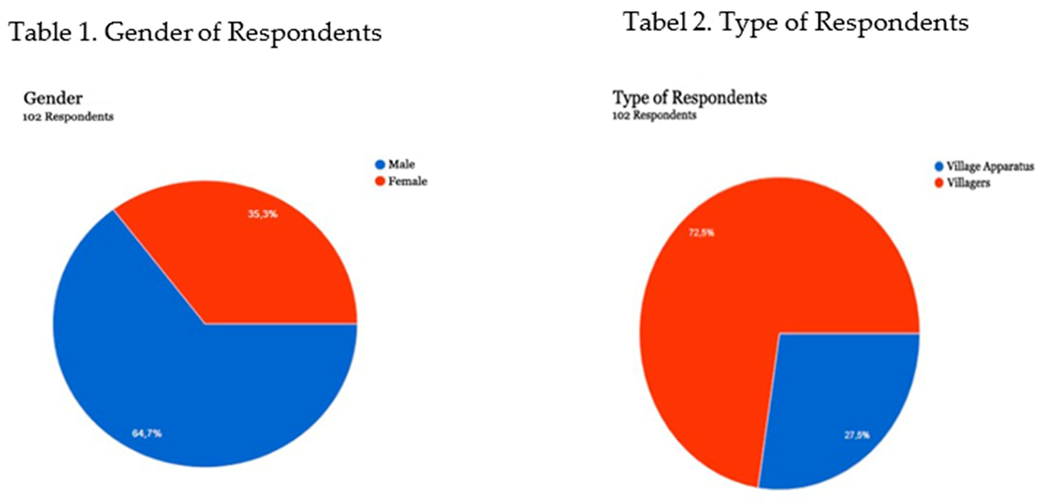

First, we take a look at the tables above, which show the gender of the respondent or informant who was asked about their situation. In Table 1 above, most of those interviewed were men, as much as 64.7%, while there were also women, as much as 35.3%. This happened because the researcher did not determine the gender of the interviewees; the interviewees were taken randomly to get information on what activities the informants would carry out if they experienced difficult conditions to survive around the lake.

While the type of informant was deliberately determined because the information was extracted starting from the main informant, namely village officials who know about village developments and the condition of the lake, as well as the regional government policies in anticipating the condition of the lake, which has an impact on the condition of the people around the lake. In Table 2 above, 27.5% of village officials became informants, and the rest is 72.5% of the community. The community was interviewed to find out how far their resilience and anticipation were towards the lake situation.

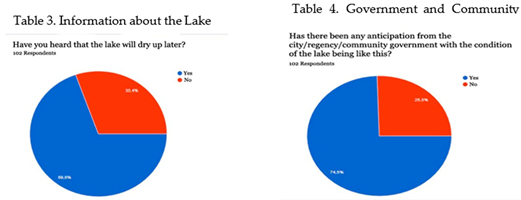

From the informants of village officials and the village people, it can be seen whether they have received information that Lake Limboto has been predicted by scientists to disappear in a few years. From the results of interviews, more than half of the informants, as shown in Table 3, which is around 69.6%, answered that they had heard about the prediction of the loss of Lake Limboto due to shallowing and narrowing. However, how to anticipate this condition based on the village government and the community answers, generally as much as 74.5% answered that they had anticipated this information as shown in Table 4. In general, village officials and the community consider that the dredging of the lake is one of the government's anticipations to prevent the loss of the lake. Nevertheless, beside dredging, the government also constructed a barrier dam between the lake and residential areas. Some people feel that this does not solve the problem, because during the rainy season, water stagnates in residential areas for months. The construction of a barrier dam tries to solve the problem of silting lake but creates new problems for residents. Hence, despite the fact that 69.6% of the community knew about predictions that the lake would dry up in less than ten years, anticipation conducted from the government, while the community and the village officials have not yet anticipated anything by themselves. The inquiry of this anticipation is actually not only the government's anticipation but also the community's anticipation over the condition of the lake.

3.3. Studying Old Text and Oral Stories

Besides the approaches involve interviewing people around the lake, to achieve this objective, an interdisciplinary method is employed, which involves the integration of many academic disciplines to comprehensively comprehend and solve the problems. This study needs to explore old texts describing the lake, oral stories, old photo documentation, maps about the lake to support the interpretation and argumentation of the field research.

3.4. Research Locations

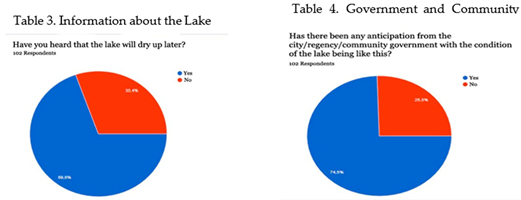

The interviews were mostly conducted around Limboto Lake in Oktober 2022, Gorontalo Province. Lake Limboto stretches more to the west, namely to Gorontalo Regency, but a little to the east still includes the city area of Gorontalo. The research area includes sub-districts and villages located in the city and regency of Gorontalo that surround the lake, namely in 27 sub-districts and villages. These villages and sub-districts are (

Figure 1): 1. Lekobalo sub-district, 2. Dembe 1 sub-district , 3. Iluta village, 4. Barakati village, 5. Bua village, 6. Huntu village, 7. Pilobuhuta village, 8. Ilohungayo village, 9. Payunga village, 10. Teratai village, 11. Limehe Timur village, 12. Ilomangga village, 13. Bolihuangga sub-district, 14. Hunggaluwa sub-district, 15. Kayubulan village, 16. Hepohulawa sub-district, 17. Dutulana'a sub-district, 18. Hutu'o village, 19. Pentadi'o Barat sub-district, 20. Timuato village, 21. Lupoyo village, 22. Bulota village, 23. Buhu village, 24. Hutada'a village, 25. Ilotidea village, 26. Tilote village, 27. Tabumela village.

3.5. Adaptation of Occupations

To see how the people living around the lake have been surviving while the lake is narrowing and shallowing, we can look at

Figure 1. This table only shows the distribution of community work in the villages around Lake Limboto. This chart does not currently show the percentage of community employment, because this research is qualitative research. This study does not intend to measure the percentage of what work is occupied by the people around the lake, but this chart only shows the results of interviews which show how the people were generally lake fishermen in the past have changed their jobs due to the narrowing and silting of the lake.

Figure 1.

Distribution of community work in Lake Limboto.

Figure 1.

Distribution of community work in Lake Limboto.

The description of the distribution of community work in the villages around the lake in

Figure 1 demonstrates that their work currently varies. In the southeastern region of the lake, there are generally still many fishermen, with two types of fishermen: catcher fishermen and aquaculture fishermen. Aquaculture fishermen are predominantly located in Dembe, Iluta, and Barakati villages, while catcher fishermen are primarily located in the villages of Tabumela, Ilotidea, Tilote, Hutada'a, Buhu, and Lupoyo. These last villages are riddled with poverty. The more the distance from the deep lake area the less the fish finding. Ironically, these villages still inherit fishermen as their occupation. In the northern region, specifically in Ilomangga, East Limehe, Teratai, Bolihuangga, Hunggaluwa, and other areas, it is very rare for communities from those places to become fishermen at present. Moreover, Ilomangga and Teratai are new villages. They established on new land from dried up lake in 1970s. Generally, people moved to this place because of the empty land that can be cultivated.

The nature of inhabitants’ job is varied as the lake gradually becomes narrower. If they become village and government officials, they generally become civil servants. They used to be fishermen then switch professions to the other jobs. This is their way of surviving due to the uncertain lake conditions. In fact, in the Ilotide'a village, there are those who have continued to be fishermen to this day but they go fishing in Gorontalo Bay, not in Lake Limboto, but they still live around the lake. Likewise, some inhabitants who speculate their fate from folk gold mining. Although based on research, folk gold mining in Gorontalo use mercury, this is dangerous for the environment because it produces environmental pollution [

16,

17]. However, despite their occupation being located at a considerable distance from the lake, these people continue to go back and reside close to the lake.

4. Culture Fluctuation, Surface Fluctuation

Culture around the lake is fluctuating in line with the narrowing and shallowing of the lake. From the interview, it appears that people around the lake were fishermen in the past, but because of the circumstances of the lake, they are changing their jobs based on the condition of the season and the surface of the lake. If the lake is full of water, they go fishing. On the contrary, if the lake is drying, they do agriculture. Nevertheless, this condition is not able to be maintained because occasionally the rainy season brings much precipitation and results in big floods, or the dry season makes the lake have insufficient water to water the land for agriculture.

Several studies generally show that the shallowing of Lake Limboto is caused by rainfall and sedimentation. However, a detailed discussion of rainfall and sedimentation itself showed that they are not an independent cause in the research of natural science perspectives. According to the study conducted by Eraku et al [

5], the influence of precipitation on the variation of the lake inundation area has diminished significantly, only by 35%. There is an accumulation of other factors that have greater influence and contribute to large alternation in the inundation area the lake. The inundation area of Lake Limboto experienced fluctuations. The result of the research demonstrated that inundation area of the lake widens or shrink almost three times less than a year.

Originally, the condition of the ebb and flow of the lake was described in the old document from 1865 written by Von Rosenberg [

18] (p. 62-63).

De vergaderbak zijnde van een tal van riviertjes en beken, die uit het omringende gebergte naar het meer stroomen, is het uit dien hoofde aan een periodiek rijzen en dalen onderhevig, afhankelijk van de in het gebergte gevallen hoeveelheid regen. Aan den zuidoostkant ontlast het zich door twee smalle natuurlijke kanalen, welke zich nabij de kampong Potanga vereenigen en vervolgens voor dit dorp door de Tapa- of Bolangorivier verzwolgen worden.

In the quote above, Von Rosenberg explains that Lake Limboto is a confluence of a number of rivers from the surrounding mountains that empty into the lake. However, at certain times the surface fluctuates depending on the rainfall in the mountains around the lake. Then, the lake water flows out through two natural canals to the southeast, then merges near the village of Potanga. Furthermore, in this village, the channel meets the Tapa or Bolango rivers. This information about a number of rivers from the old documents of the Dutch is the same with what have been researched by some experts on their articles [

4,

6,

19]. Also, the fluctuation of ebb and flow on the lake have discussed by Eraku et al. [

5] in relation to the inundation area on the lake.

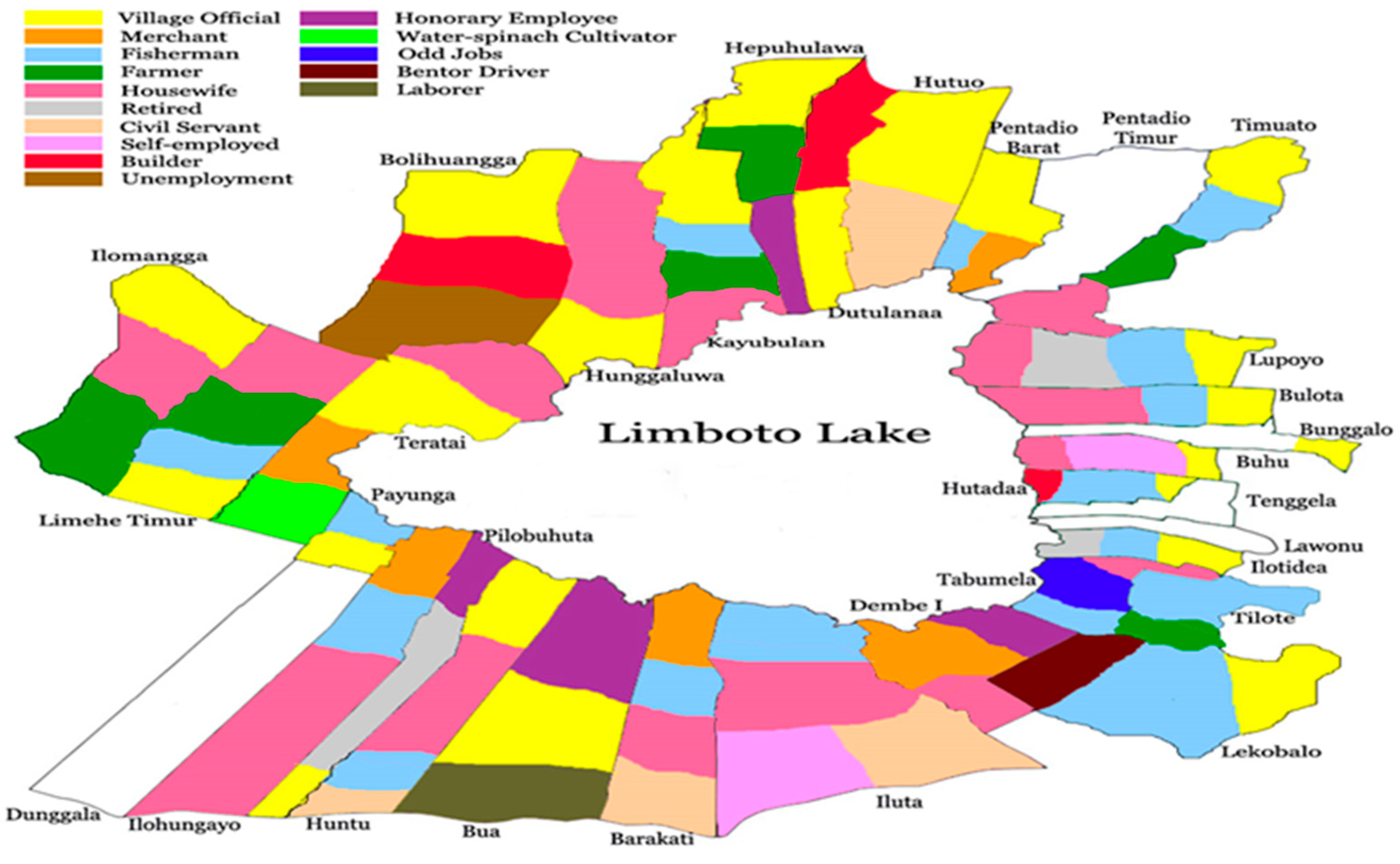

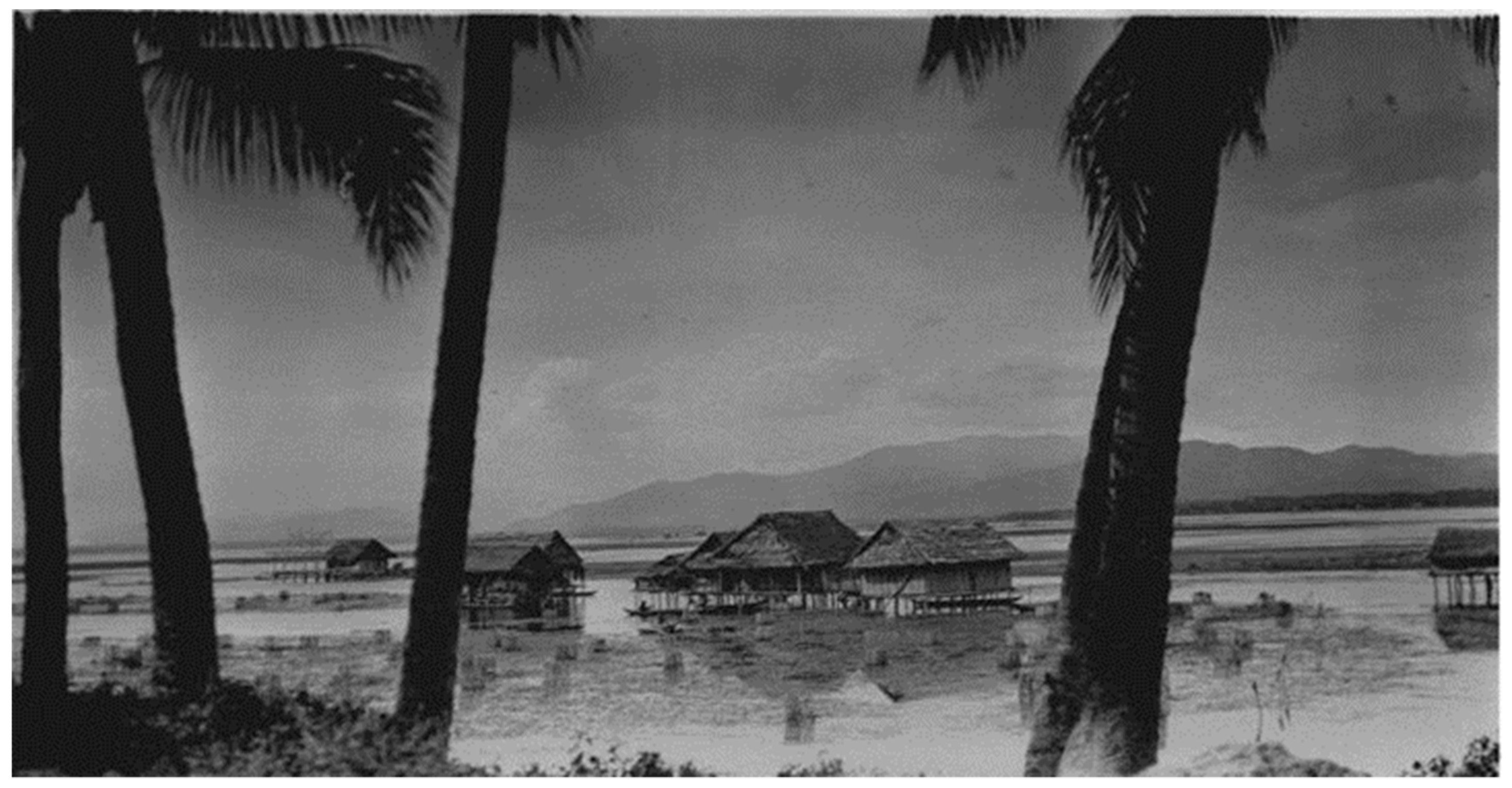

Documentations obtained from the Tropenmuseum [

20,

21,

22] show that since past times people have always lived on the shores of Lake Limboto which was rather shallow in stilt houses, as shown in the photos’ documentation below.

Figure 2.

Plank house on Lake Limboto circa 1900-1930.

Figure 2.

Plank house on Lake Limboto circa 1900-1930.

Figure 3.

Plank houses on Lake Limboto around 1924.

Figure 3.

Plank houses on Lake Limboto around 1924.

Figure 4.

Plank House on Limboto Lake circa 1924.

Figure 4.

Plank House on Limboto Lake circa 1924.

In the images from the years 1900s above, it is obvious that the people who dwelled near Lake Limboto built wooden plank houses in the shallower regions of the lake. In the past, people anticipated the ebb and flow of the lake water because, long ago, the water level was always going up and down. However, the presence of elevated plank houses mitigated the impact of flooding since these structures were situated at a higher elevation than the lake level. Accordingly, the flooding was not noticed. Moreover, in the past, the lake was still deep, and the process of sedimentation was comparatively less significant than its current state.

From Von Rosenberg's description [

18] (p. 56-58) about his trip on the lake, we got information about the settlements on the lake. Von Rosenberg embarked on his voyage using a vessel known as a

blotto (the name for a boat from native people; actually, it is called

bulotu). This voyage took place along the Tapa (Bolango) river, leading to the Potanga region, and arriving at the lake. It indicates that during that period, the rivers in Gorontalo were used as a mode of transportation to access the Limboto region. He saw houses dispersed close to the riverbank, where the riverbanks were planted with various plants such as bananas, corn, coconuts, and other plant species. Upon the boat's arrival in the lake, Rosenberg's attention was drawn to the presence of the residences close to the lake. He anchored in Bolilla Village (now it calls Bulila). He stayed in a guest house situated at a distance of approximately a hundred meters from the lake. This description refers to the fact that, since the 19th century, the lake area has already been inhabited. In another part of Von Rosenberg's writing, it is depicted that generally houses in Limboto, Gorontalo were stilts houses and built of planks and bamboo, even Radja's house was built with similar materials, the difference was that it was a pavilion and there was a mosque. The images sourced from the Tropenmuseum also strengthen the customs of the local inhabitants residing near the lake building their stilt plank houses.

Currently, people around the lake construct houses made of stone or permanent houses on the site of the dried-up lake [

3,

11]. Consequently, during the rainy season and when the lake overflows, their residences are inundated by floodwaters reaching up to the level of the roofs. The circumstances have never been considered by the community built permanent houses at the location of the dried lake. Accordingly, in the event of a water overflow, a disaster cannot be avoided because the community is indeed at the location of the dried lake part.

From the interview with the former head village of Ilotidea, it is informed that people around the lake approximately in the 1980s built stilt houses on the lake in the past. The houses were up to two meters from the ground, but when the lake began to dry, they build stone houses on the ground precisely on the lake area. No wonder, if the floods hit, the houses would sink, covered by water up to the roof. The research of Kasamatsu et al. [

2] also stated that floods are frequent happen and it affects big changes to human life and ecological system. When floods were happened, water stayed around houses during months. People must vary the life and occupation, especially fishers and farmers. Rapidly decreasing of lake area brings big influence in people’s life.

People in the past used to anticipate the water level in the lake, because they lived in stilt or plank houses in ancient times, so the impact of the ebb and flow of the lake water did not have much impact on the people around the lake. Currently, Lake Limboto is shallowing and narrowing, there has been a notable trend of constructing permanent structures on the formerly submerged portions of the lake. Base on the field observation, the anticipation of the community around the lake was normal in the past based on past habits of living in the lake area. However, considering the current circumstances of the lake, the anticipation needs to be improved, because the lake basin become flattened, meanwhile the local people built permanent and low building.

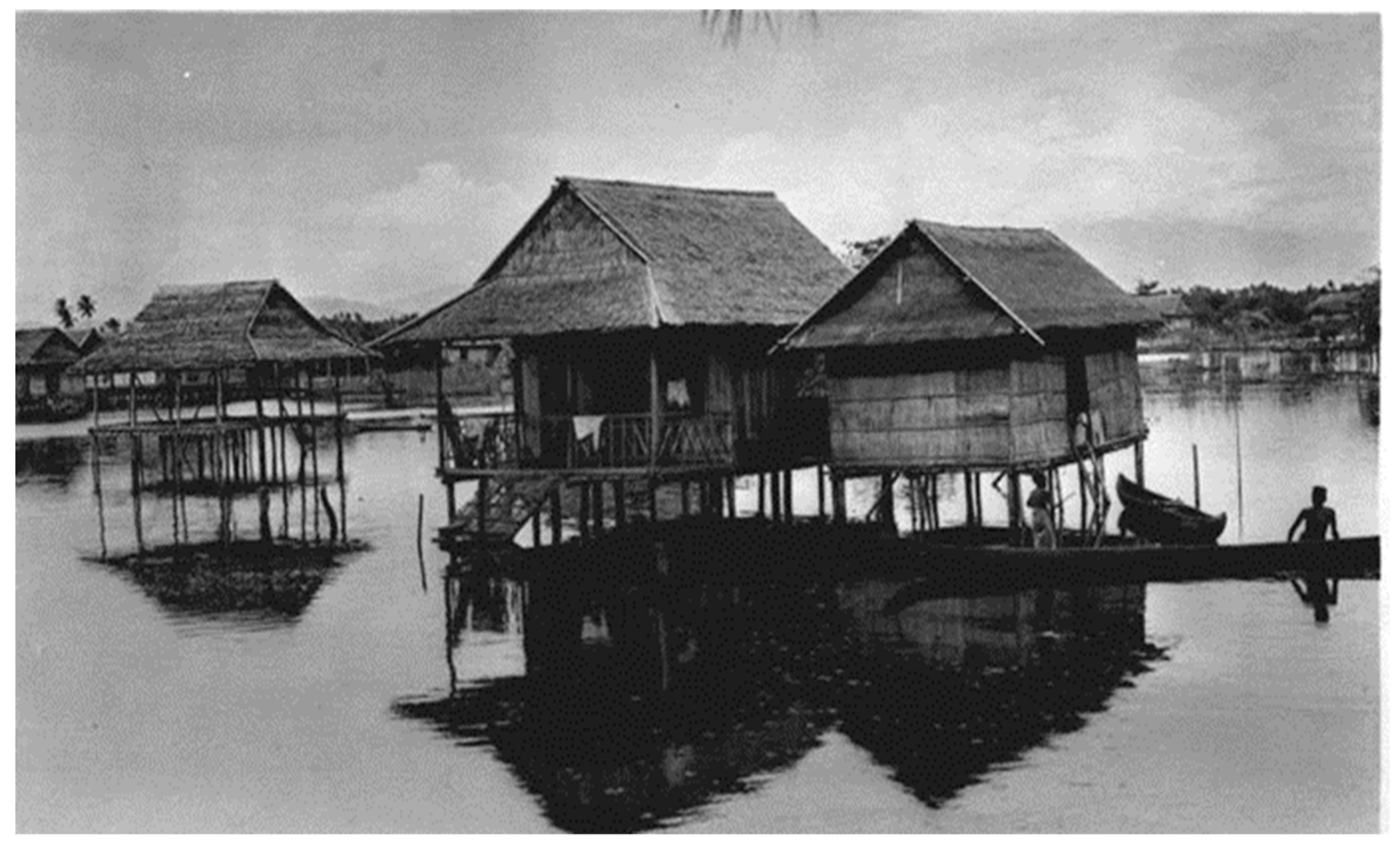

5. Alternation of Lake Size, Alternation of Settlements Model

The current dimensions of the lake have experienced a reduction of over two-thirds compared to its dimensions in the year 1863. According to data from 1991, the lake has narrowed by about 4,000 hectares, from an original extent of 7,000 hectares to 3,644.5 hectares, and is still declining in 2017, with the lake area barely reaching 2,639 hectares. This shrinking process is further supported by the findings that the shrinkage of Lake Limboto is driven by sedimentation causes and the withdrawal of land from the northern side of Sulawesi [

19].

The findings of Kasamatsu et al. [

2] demonstrate that a significant amount of sediment flows into the lake every year, resulting in a reduction in water depth and a narrowing of the lake's surface area. The quantity of sediment is estimated at 1.5 million m3 per year, and it is estimated that the lake will disappear in a time frame of 10–20 years. Segmentation is a significant and substantial challenge. The cause of the erosion is agriculture activities in the mountainous area. Since several rivers flow to the lake, they bring much sediment to the lake; the Alo-Pohu River from the west area of the lake is the primary one, and it brings 63.8% of sediment. Therefore, the shrinkage of the lake runs rapidly. It was 7,000ha in 1932, 4,000ha in 1960, and 1,900–3,000 ha in 1999. In line with Kasamatsu et al., the results of a study by Alfianto et al. [

7] stated that the Alo River has the greatest potential for channelling sedimentation from upstream and towards Lake Limboto. This research also shows that the Biyonga Baluta River has the greatest potential to carry sediment resulting from land erosion.

Nevertheless, the deeper study about sedimentation from Kimijima et al. [

6] demonstrated that based on remotely sensed imagery and river outcrop investigation data, the rapid shrinkage of Lake Limboto experienced certain mechanisms. The results indicate that during the period from 2003 to 2017, the process of riverbank erosion caused rivers to drain into the lake, which contributed to more than 70% of the sedimentation resulting in shrinkage. The geological investigation found that the lowland area in the western area of the lake comprises 1 m of flood sediments, followed by at least 5 m of fine-grained inner bay sediments. Moreover, severe riverbank erosion is also observed at many points. Therefore, it can be inferred that the reduction in size of Lake Limboto resulted from rapid-induced erosion of inner bay sediments which were formed as a result of tectonic plate collisions. These sediments were easily transported and deposited into Lake Limboto, leading to the formation of a delta, especially on the west side of the lake. The process of accelerated sedimentation caused by river erosion has led to rapid lake shrinkage.

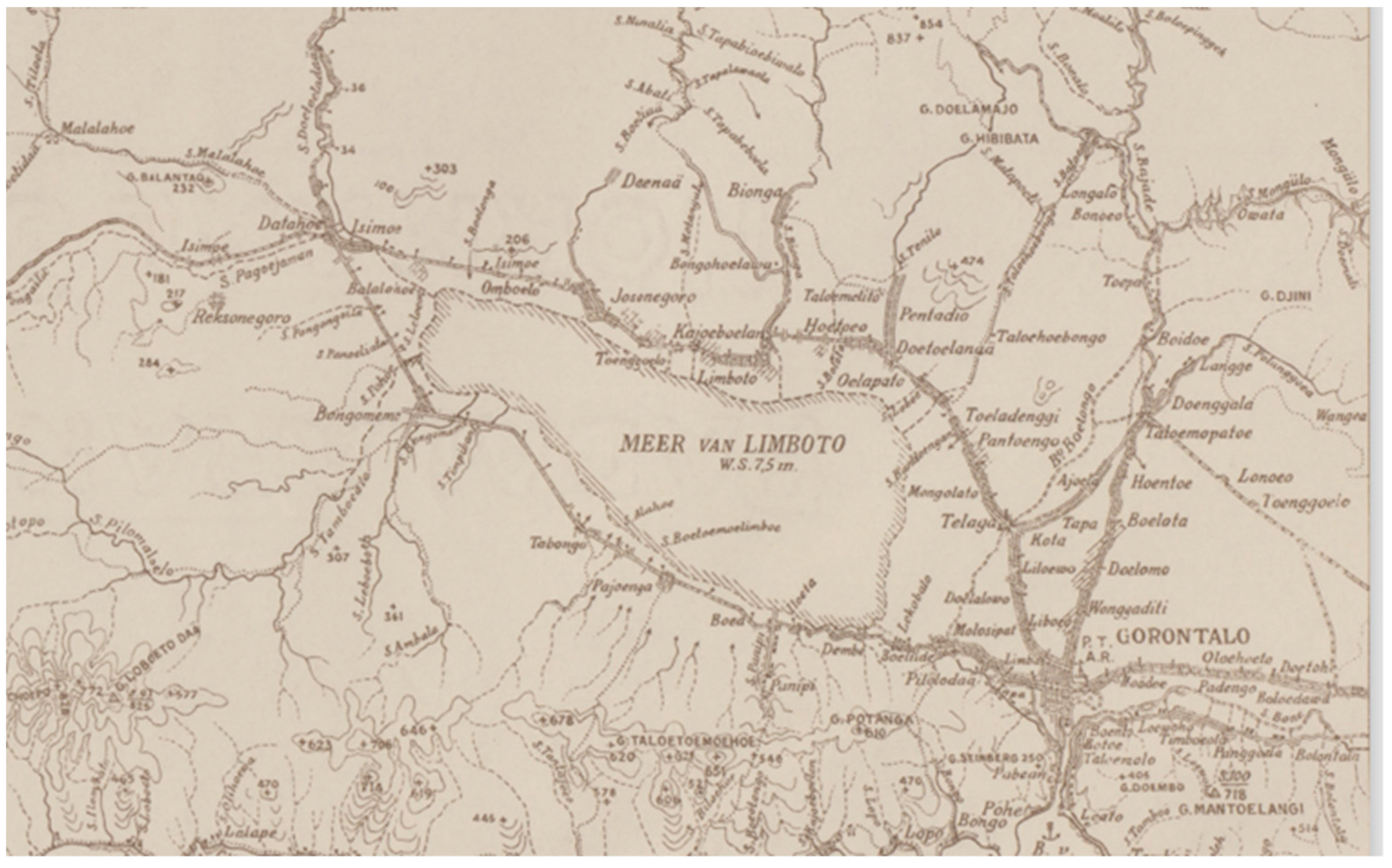

This information is important because the lives style of people around the lake change along with changes in the size of the lake. According to the map dating from the 1941 [

23] period from the Dutch Colonial Maps, it is evident that the size of Lake Limboto was very wide.

Figure 5.

The Size of Lake Limboto in 1941.

Figure 5.

The Size of Lake Limboto in 1941.

The provided map visually illustrates the presence of Lake Limboto's northern section traversing the Yosonegoro (Kampung Jawa) region. This is showing the extent of Lake Limboto during the specified period. The travel report by Von Rosenberg [

18] (p. 62) provides a description of the lake's dimensions and depth. He illustrated that Lake Limboto, better known by the natives as

"Bulalo Mopatu" (Warm Lake), covers the western part of the lake which protrudes slightly to the west. The lake is elliptical in shape without a deep curve. The length of the lake is approximately 18 kilometers and a width of 7.5 kilometers. Von Rosenberg did not give the exact depth of the lake, so he likely did estimate the depth of Lake Limboto to be between 2½ fathoms plus a few feet. This was the size in 1863 [

2].

Figure 6 demonstrates how Lake Limboto has been drastically shrinking more than two third from its original size in less than a hundred years when compared with the maps in Figure 4. Then, the lake areas that have dried up have turned into settlements. Based on the findings derived from field interviews, it was found that in the 1970s, the area of the lake that had dried up was used as a settlement by the local community. Notably, there were people from Suwawa, the eastern part of Gorontalo, moved to the former lake area. A specific instance of this movement can be found in Ilomangga village, situated in the northwest of the lake.

The area, now called Teratai, Ilomangga, and East Limehe villages (see

Figure 1), is part of the lake. When the area dried up, people-built settlements and opened fields in this area. However according to the community, these areas still had water in the form of swamps in the 1970s, but the area was already very shallow. When the area is completely dry, people occupy it. After all, at that time, there was no prohibition on establishing settlements in the former body of the lake, so many people moved to occupy the lake area that had dried up.

Figure 6.

The current size of Limboto Lake decreased more than two third.

Figure 6.

The current size of Limboto Lake decreased more than two third.

Based on the observed alterations in the dimensions of Lake Limboto, it is evident that less than a hundred years, the lake has transformed drastically in terms of size and depth. It provided chance to people residing on the new land. Nevertheless, if rainwater comes to fill the lake plains, the water becomes a flood disaster because the surface of the lake, which has flattened, is no longer in the form of a basin. It hit the people settlements around the lake.

6. Power of Place, Power of Belonging: Survival and Resilience

People living around the lake are generally poor, moreover the currently water quality of the lake is also poor so it cannot provide good productivity of fish. Surprisingly, the people still live next to the lake. This implied a power of place, that created power of belonging. The power of place shows that place has meaning. The term "place" has more complex than the word location implies. It is a distinct thing, a special ensemble that has a history and meaning. Place incarnates the experience and aspiration of people. It is a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspectives of the people who have given it meaning [

13].

It is known from the old documents that there were people living along the banks of Lake Limboto since more than 150 years ago. Through photos, and maps from the early twentieth century shows that there were houses on stilts built on the banks of the lake. This shows that the lake area is considered to belong to the community because they have been there for hundreds of years. They live in the lake area because, generally, they have been fishermen for generations. This sense of belonging is inherited along with the work as a fisherman and has been passed down from generation to generation. This is the reason why they do not have an inclination to move to another place regarding the condition of the lake, and even though they live around the lake in poverty, that is the first reason.

The second is that the lake is productive and fertile, so the lake shaped their lives. The evolution of the lake goes in line with the evolution of the inhabitants' lives. The inhabitants tried to adapt to the condition of the lake based on the changes of the season. By following the lake's fluctuating conditions based on the weather, local residents take advantage of it to survive. In fact, the lake actually started to narrow, and its function as a water reservoir began to diminish. As a result, it became less productive and unfertile. Here, it can be seen that local residents are trying to position themselves in the situation they are facing. In the rainy season, they become fishermen. In the dry season, they do farming. The survival and resilience of the people were referred by adapting their jobs. These two reasons above show how the people around the lake made meaning of Lake Limboto for their lives, namely that they have been there for hundreds of years, and in that place, they based their lives.

Places have two types, namely public symbols and fields of care. First, public symbols are places that can organize space into center of meaning. These places are consciously created, and their meaning are consciously manipulated. Second, fields of care are places that become meaningful as emotionally charged relationship between people and particular site through repetition and familiarity [

13]. Baldwin et al. [

13] gave example among others sacred place as public symbols, and home as fields of care.

From this framework, we refer how people around the lake Limboto were tied with that place. It is field of care for them. That lake is home for them for centuries. At the same time, there is also public symbol that was created centuries ago. The lake had been valued as a blessed lake, if we connect the two oral stories about the lake, namely the legend of Mbui Bungale and Du Panggola [

24,

25]. It should be noted the way of thinking of the inhabitants, they feel tied to the lake area as public symbol and field of care. In spite of the lake was dying, they still thought they could survive in that place. They did not move from that place to look for a living, even though the Gorontalo area is spacious. They just change jobs following the fluctuation of the condition of the lake; some even remain fishermen, either lake fishermen or sea fishermen, but they still belong to the lake area.

However, the definition of people-place relationship as above only sees it as applying the same to all people, all places and at any time. In fact, it is also important to see how different people give meaning to a place. Although the meaning of public symbols and fields of care concern remains, place must be examined contextually and not separate it from the "life world" or culture. This understanding of place cannot be separated from social, economic, political and cultural relations which implies the existence of power relations [

13]. The context of social, economic, political and cultural relations is bound together to make meaning for the place.

In the case of Lake Limboto, there are at least three interest groups in interpreting this place: the initial group of people who have lived in the lake environment for hundreds of years; the new communities living on new lands that have emerged since the 1970s; and the government. These three groups have their own sense of place on Lake Limboto, so they make meaning for this place. The meaning of the lake was constructed through the social interactions among these three groups with the lake environment. Actually, the intense interaction is between the government and the two group of society around the lake. The government always views the community as having to be regulated politically in the interests of preserving the lake without considering the community's sense of place. In the case of the construction of a barrier, this actually creates new problems, and the issue of land rights shows how the government interprets the lake from their perspective. Meanwhile, for the initial community groups who felt they belonged to the lake, the government did not solve the problem. The current position of the initial group of people no longer sees the lake as a place to live for good but rather as a home and sacred place (a field of care and public symbol), because they survive in that place even though they are no longer lake fishermen. Historically, they have lived in that place for centuries, so the lake is home for them, which all happiness and pain experienced, and that is more meaningful than a land certificate. Likewise, the new community groups that occupied the dry lake land, initially had to survive due to economic problems. They opened agricultural land on the former lake land. They view the new land as home because they have been living in the area for more than fifty years, even though it might be the lake area has not yet become a public symbol for them.

7. Conclusions

Based on the findings and discussion above, we discovered that activity fluctuations around the lake following the fluctuation circumstances of the lake. The varying occupations of the people, which was formerly made up of lake fisherman but had to diversify in order to survive, demonstrate how the relationships and activities of the communities surrounding the lake fluctuate and change along with the changes in the lake's shape and time.

The critical condition of the lake and the threat of being lost do not make people leave the lake location. In fact, in the meaning that the lake was their life still alive. They try to survive and have the resilience to stay in the lake location with generally poor living conditions. A sense of place or place of belonging, which is formed through history, familiarity, and repeated interaction with the place, makes the community tied to the lake because the lake is their home. The feeling of being at home and the existence of culture of building permanent house relate to the prosperity, moreover enhancing the social class make people modify their residences into permanent buildings. It refers also to the thought of forever dwelling in that place regardless of floods hit.

By looking at the fluctuating activity patterns of the lake community, we can see that the community has actually responded to the lake situation, but they do not imagine that the lake will really disappear because the cycle in their lives has so far occurred only in the dry and rainy seasons. They did not notice that the size of the lake was getting smaller. Therefore, people should have anticipated the prediction of the disappearance of the lake because they will lose “their homes”, which means the loss of their culture and social interactions. The government should not only anticipate the condition of the nature but also pay attention to the humanitarian; how the community interprets the lake for their lives in historical, social, economic, political, and cultural contexts. The disappearance of the lake will be a disaster for nature and social culture as well.

Author Contributions

M.B. contributed to design of the research, conducted data collection, data analysis. M.J. project administration, and conducted the investigation of old and current lake size and dimension in the field with the supervision of M. S. M. S. and H. K. provided conceptual advice and critical comments. M. S. funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN: a constituent member of NIHU)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge the supported funding from the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN: a constituent member of NIHU), Project No.14200102; and the support of this research collaboration with Universitas Negeri Gorontalo (UNG).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- R. N. S. Clair and A. C. Williams, “The framework of cultural space,” J. Intercult. community, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1–14, 2018.

- H. Kasamatsu, M. Jahja, Y. Indriati Arifin, M. Baga, M. Shimagami, and M. Sakakibara, “Prior Study for the Biology and Economic Condition as Rapidly Environmental Change of Limboto Lake in Gorontalo, Indonesia,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 536, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Junus and K. Z. Mamu, “Arrangement and Regulation of Lake Area Policy,” J. Yuridis, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 136–156, 2019.

- S. L. Mahmud and N. Achmad, “Analisis Dinamik Model Pendangkalan Danau Pengerukan Endapan Dynamical Analysis of Mathematical Model of Limboto Lake Silting with Water Hyacinth Cleaning Solution,” BAREKENG J. Ilmu Mat. dan Terap., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 597–608, 2020.

- S. Eraku, N. Akase, and S. Koem, “Analyzing Limboto lake inundation area using landsat 8 OLI imagery and rainfall data,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1317, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kimijima, M. Sakakibara, A. K. M. A. Amin, M. Nagai, and Y. I. Arifin, “Mechanism of the rapid shrinkage of limboto lake in Gorontalo, Indonesia,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 22, pp. 1–14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alfianto, S. Cecilia, and B. W. Ridwan, “Pemodelan Potensi Erosi Dan Sedimentasi Hulu Danau Limboto Dengan Watem/Sedem,” J. Tek. Hidraul., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 67–82, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Noor and M. Ngabito, “Tingkat Pencemaran Perairan Danau Limboto Gorontalo,” Gorontalo Fish. J., vol. 1, no. 2, p. 30, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hasim, “Perspektif Ekologi Politik Kebijakan Pengelolaan Danau Limboto,” Publik (Jurnal Ilmu Adm., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 44, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Akbar, A. Alwi, N. I. N. Indar, and M. T. Abdullah, Adaptive Governance In Terms Of The Limboto Lake Management Network, vol. 8, no. 4. 2021.

- M. T. Z. Sarson, “The Legal Status of Certified Land Ownership of People Inhabiting around Limboto Lake,” Indones. J. Advocacy Leg. Serv., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 5–18, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Barker, Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 2000.

- E. Baldwin, B. Longhurst, S. McCracken, M. Ogburn, and G. Smith, Introducing Cultural Studies. Edinburg: Pearson Education Limited, 2008.

- T. Giles, J., & Middleton, Sudying Culture A Practical Introduction. Oxford and Massachusetts: Blackwell Publisher, 1999.

- D. Oswell, Culture and Society. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 2006.

- Y. I. Arifin, M. Sakakibara, S. Takakura, M. Jahja, F. Lihawa, and K. Sera, Artisanal and small-scale gold mining activities and mercury exposure in Gorontalo Utara Regency, Indonesia, vol. 102, no. 10. Taylor & Francis, 2020.

- P. Metaragakusuma, M. Sakakibara, Y. I. Arifin, S. M. Pateda, and M. Jahja, “Rural Knowledge Transformation in Terms of Mercury Used in Artisanal Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM)—A Case Study in Gorontalo, Indonesia,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 20, no. 17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Von Rosenberg, Reistogten in de Afdeling Gorontalo gedaan op last der Nederlandsch Indische Regering. Amsterdam: Frederik Muller, 1865.

- M. Jahja, Y. I. Arifin, N. A. Gafur, F. Masulili, A. P. M. Kusuma, and M. Sakakibara, “Performances of Erosion Control Blanket Made From Palm Fiber On Reducing Erosion In The Slopes Of Lake Limboto Basin,” E3S Web Conf., vol. 400, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Collectie Troppenmuseum, Paalwoningen in het meer van Limboto TMnr 60014257. Danau imboto, Gorontalo, Indonesia, 1900.

- Collectie Tropenmuseum, Paalwoningen in het meer van Limboto TMnr 60014261. Danau Limboto, Gorontalo, Indonesia., 1924.

- Collectie Tropenmuseum, Paalwoningen in het meer van Limboto TMnr 60014256. Danau Limboto, Gorontalo, Indonesia., 1924.

- T. D. (Batavia), Gorontalo. No place, unknown, or undetermined: Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden, 1941.

- Oputu, “Asal Mula Danau Limboto,” UPT.TIK UNG, 2012. https://mahasiswa.ung.ac.id/821412081/home/2012/9/7/asal_mula_danau_limboto.html.

- N. Tuloli, Cerita Rakyat Kepahlawanan Gorontalo. Jakarta: Lamahu, 1993.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).