1. Introduction

Climate change is undoubtedly one of the greatest threats for the environmental sustainability, human health and well-being globally [1 -3]. According to the scientific community, the main cause that intensifies the negative impact of climate change is human activity [

1], it is realized that the success of relevant environmental programs depends to a large extent on the personal attitudes of employees [

4]. Furthermore, beyond human activity, the organizations of each sector are an important factor as their mode of operation results in the worsening of the environmental effects of climate change. With more than 9 million deaths worldwide and economic losses of 4 to 6 trillion dollars by 2015 [

5], and over 560 billion in the EU Member States over a period of approximately 40 years (1980-2021) [6[, the need for a radical change in the perception of climate change is more than necessary. The healthcare sector is one of the main factors with a strong negative environmental footprint as it is responsible for more than 4% of global emissions [

7], while at the same time absorbing a large percentage of financial resources as an increase was recorded, for the year 2020, reaching 9 trillion dollars (approximately 11% of global GDP) [

8], against 8.3 trillion dollars (10% of global GDP) which was in 2018 [

9], which was caused by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis [

8].

Along with climate change, humanity has also been faced with other important issues such as population aging, climate change and social inequalities with the finding of innovative solutions being imperative while the adoption and implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development such as it was formed and approved by all the states of the United Nations in 2015, it is a one-way street [

10]. The above has constituted a growing pressure on all sectors of the economy which is most evident in health organizations. Therefore, the mode of operation as well as the other activities of health organizations become particularly important as they have a direct impact on the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially in issues related to the promotion and maintenance of health and well-being, the promotion of gender equality ensuring drinking water as well as ensuring clean energy [

11]. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of an efficient and quality health sector and reminded of the significant impact it has on the social and economic well-being of the population in times of crisis where the endurance of each system is tested [12-14]. The uncertainty of the macroeconomic environment in parallel with the ever-increasing desire of individuals to achieve their well-being pushes the health sector into a long struggle to meet the needs and expectations of all economic actors, from individuals and businesses to the state [

15]. According to the scholars in the field and the current literature, the sustainability of an organization is not strictly limited to the environmental dimension, but extends to both the social and economic dimensions [

16]. In particular, the application of “green” technologies, the reduction of waste and harmful emissions, the recycling and re-use of materials and the strengthening of society’s awareness regarding environmental issues, establish the environmental dimension [

17]. As for the social dimension of sustainability, it is determined by ensuring human rights, eliminating discrimination, promoting equal access to public goods and services as well as other related activities aimed at improving social capital and creating networks in society [

18]. Finally, the economic dimension of sustainable development entails ensuring a high level of economic development and living standards through the reduction of energy consumption and waste, the fight against poverty as well as the resolution of other economic problems that concern the community [

11]. So far, many efforts have been recorded by healthcare organizations to adopt sustainable practices to reduce their environmental footprint globally [

19]. Taking into account the complexity of health systems, and the fact that the healthcare sector is a labor-intensive industry where human resources is the leading productive factor, it is necessary to promote green behavior as well as education about environmental issues in the workplace so that not only to adapt organisms to climate change but to minimize further environmental degradation as much as possible.

This article undertakes a research approach to examine the intricate relationship between climate change and its repercussions on the healthcare sector. Specifically, it delves into the capacity of hospitals and healthcare structures to navigate the continuous challenges posed by the impact of climate change. Moreover, it investigates the extent to which hospitals aspire to adopt environmentally sustainable practices, not only in their strategic business planning but also in the overall behavior of both the organization and its workforce. This encompasses a commitment to address environmental degradation and contribute to mitigating the escalating effects of climate change. Recognizing a conspicuous gap looking for relevant studies. Subsequently, we embarked on crafting a targeted empirical study, conducted within the context of Greece, where the research gap proved to be notably larger. In the context of the research, the following research question was created and will add special scientific value not only to the international literature, but especially to the Greek research data, covering gaps, as it will give a clear picture of the existing situation in a healthcare organization in terms of dealing with and understanding climate change.

Research Question (RQ): ‘‘Does the organizational behavior plays a pivotal role in driving the effective implementation of sustainable policies and actions within a healthcare organization?’’

The articulated research question has given rise to several nuanced sub-questions, each comprehensively addressed below, offering a more precise and holistic approach to the central inquiry. Specifically, these sub-questions delve into: 1) the consideration given by hospital administrations to climate change, examining the extent to which they endeavor to operate healthcare organizations in an environmentally friendly manner by integrating climate provisions, adhering to European Union guidelines, and aligning with other relevant organizations, 2) the proactive measures taken by hospital administrations to voluntarily address the impacts of climate change, 3) an exploration of the leadership’s role in motivating staff to adopt environmentally friendly practices in their daily operations and 4) the degree to which healthcare professionals prioritize environmental concerns and actively engage in initiatives of their organizations addressing climate change.

Structured in response to these premises, the research unfolds in a systematic manner.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive overview of existing literature, drawing from reputable academic journals, international, European, and national organizations, as well as stakeholders in the climate discourse. In

Section 3, past research endeavors are examined, highlighting the imperative for hospital administrations to prioritize not only financial considerations but also the fostering of social and ecological benefits, thereby reducing their environmental footprint.

Section 4 outlines the materials and methodology employed in the study.

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7 rigorously analyze and discuss the research findings, addressing identified gaps, proposing avenues for future academic research, suggesting theoretical and practical implications for healthcare organizations, and acknowledging limitations. The article concludes by summarizing key insights and offering concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

As stated in the introduction, in the coming years all health structures will have to make changes to achieve a more sustainable course in order not only to survive as organizations but also to ensure the health and well-being of both people and the environment [

20]. Health workers, play a particularly important role as members of the organization as they can significantly contribute both to the implementation and promotion of green behaviors within its operating contexts [

21]. The healthcare sector is undeniably an extremely demanding work environment whose main concern is the promotion and maintenance of people’s health [

22], therefore voluntary green behavior by health workers is not enough. In order to record significant progress in the implementation of sustainable actions in health organizations, it is necessary to strengthen the effort and create a supportive climate from the leadership towards the employees in order to primarily achieve their well-being and job satisfaction [

23]. The above leadership style is called sustainable leadership and aims to achieve and ensure the balance between the human resources of the organization and the protection of the planet [

24]. The effectiveness of sustainable leadership is most evident in times of intense environmental challenges as it emphasizes environmental diversity, encourages learning around environmental issues, effectively manages all stakeholders, attempts resource development in an environmentally friendly manner while emphasizing friendly relationships with personal and social, ethical and responsible behavior [

23]. In addition to the above, carrying out the right actions, in the right way within a health team in stressful moments is inextricably linked to the diffusion of knowledge and the creation of a common framework of knowledge [

25]. For example, effective procedures that can minimize the potential risk of infection by a virus should be communicated to healthcare personnel [

26], so that they feel safer. Organizational Behavior Analysis delves into the behavior of individuals of the groups within an organization, as well as the structure itself [

27], aiming to examine how people interact, communicate, and make decisions [

28]. Based on the above, the administrations of health organizations, by integrating some of the basic principles of organizational behavior into the basic body of the organization’s operation, will be able not only to shift from the classic form of leadership to sustainable leadership, but will also manage to raise awareness to educate all health workers about environmental issues and motivate them to adopt sustainable practices in and outside of work achieving in this way both the assurance of the quality of health services for the citizens of society and the reduction of environmental degradation. In conclusion, the achievement of the adoption of green policies and actions with the aim of improving the environmental footprint of health organizations requires a collective effort that will start from the administration and will end with the employees of the health structures, while at the same time they should develop philanthropy and cooperation and at a more general level with society so that the organization can help in practice and other social issues that plague humanity.

3. Research Background

As already mentioned, the adoption of green and environmentally friendly policies, the use of new technologies, the creation and integration of environmental actions in the general operation of a health organization in parallel with the awareness of staff about environmental issues are considered fundamental components not only for the sustainability of a health organization but also to ensure the health of people and the planet [29-35]. All of the above makes it necessary to have an administration that thinks and operates green while at the same time trying to educate and be included in decision-making. According to related research carried out by Lee & Lee, 2022 [

29], it emerged that the role of top management is the cornerstone in terms of encouraging the active participation of employees in the environmental policies it implements, the continuous education and training of staff, the continuous improvement and environmental performance of the organization. The above finding suggests that both the implementation and the degree of success of green hospitals are inextricably linked to the commitment and participation in green health care activities primarily from the top layers of management [

36]. Although in many cases of health structures the development of environmental actions is attempted without the involvement of the staff [

37], the relevant literature has indicated the involvement of personnel as one of the fundamental success factors of such actions. Therefore, the administrations of the hospitals should in the next period and in the following years proceed with the implementation of green activities which are oriented towards the active participation of the staff as in the health sector the health workers are the backbone of the system and are able to reduce waste, provide timely information on green programs, identify opportunities to save resources and provide important feedback on policies and actions already in place so that management can assess the progress of actions and make the necessary disruptive changes movements [

29].

In another study conducted by Renee, 2021 [

38], titled “The Growing Link Between Climate Change and Health,” members of the Insights Council, including clinical physicians, clinical leaders, and executives in organizations directly involved in healthcare worldwide, were surveyed. The study found that 69% of the participants reported that it was extremely or very important to them personally that their organization implements policies and procedures to reduce its impact on climate change. Respondents also stated that 69% of clinical physicians, 67% of clinical leaders, and 54% of executives have high or moderate realization of the impacts of climate change on health. Overall, the members of the Insights Council clearly acknowledge the implications of climate change on healthcare delivery, with 80% of respondents outside the USA and 70% of USA respondents reporting mild to significant impacts. More than a quarter of the Insights Council members reported that their organization has not taken measures to increase resilience, while slightly over a quarter of respondents stated that their organization has not taken measures to reduce its impact on climate change. Furthermore, only 8% of US respondents’ organizations and 13% of non-US respondents’ organizations have taken actions to mitigate the effects of climate change.

One other example that point out the importance of organizational behavior in the application of sustainable practices in healthcare organizations, is the case of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) [

39]. The VHA is probably the largest and most comprehensive healthcare system in the United States, responsible for providing care to approximately nine million veterans per annum. In recent years, similar to many other healthcare organizations, the VHA has focused its attention on practices that focus on protecting the natural environment by reducing its environmental footprint while simultaneously improving patient care. One of the initiatives it implemented was the Green Environmental Management System (GEMS), established in 2008 [

40], GEMS is a framework designed to identify and manage environmental risks and opportunities. It includes a variety of tools and resources that enhance the VHA’s efforts to improve its environmental stance and culture. Some of the benefits of implementing GEMS included reductions in energy consumption, water usage, waste generation, as well as the use of hazardous materials. It also succeeded in improving air quality. The success achieved can be attributed, among other factors, to the adoption of principles of organizational behavior [

41]. Specifically, it is emphasized that the VHA is governed by a strong culture of collaboration and communication, which, as mentioned earlier, serves as a fundamental tool for developing and implementing such initiatives. Another important characteristic of the VHA is its highly trained personnel, characterized by high levels of commitment to the organization’s mission. Through this dedication, a high degree of employee participation in similar sustainability initiatives is accomplished, which serves as a significant motivator for the adoption of innovative work methods that support sustainability goals. The VHA’s emphasis on developing sustainable policies and actions not only advances the protection of the natural environment but also ensures quality and holistic patient care. By reducing energy consumption and significantly limiting waste, the VHA was able to allocate more resources to provide high-quality healthcare services to veterans.

While numerous bibliographic references underscore the significance of leadership and the incorporation of organizational behavior principles in the effective implementation of green policies and actions, as well as in motivating healthcare workers to consider their environmental footprint while working, the supporting research confirming this discovery remains scarce. Having identified relevant studies concerning the specific scientific field at an international and European level and taking into account the absence of relevant research in Greece, the present research attempts on the one hand to strengthen the international literature and on the other hand to establish a new research field of interest adapted to the Greek data.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Population Delimitation

The present study covers all employees working in the Administrative, Medical, Nursing, and Technical Services of public and private healthcare facilities in the Hellenic Republic. Therefore, all participants in the study are adults (over 18 years old) and proficient in the Greek language.

4.2. Sampling Method – Sample Size

The sample consisted of 379 employees from either a public hospital or a private clinic who belonged to one of the aforementioned services (Administrative, Medical, Nursing, and Technical). The sampling method used was Convenience sampling.

4.3. Instrument Development

The questionnaire used in this research effort was developed by the researcher. It consists of a total of 23 questions and is divided into three subcategories (Organizational Attitude towards Climate Change, Climate Change Initiatives and “Green” Behavior, and Personal Attitudes and Thoughts about Climate Change and the Environment), with some demographic questions included. Specifically, for the category “Organizational Attitude towards Climate Change,” a total of ten (10) questions were developed, seven (7) questions for the category “Climate Change Initiatives and ‘Green’ Behavior,” and six (6) questions for the category “Personal Attitudes and Thoughts about Climate Change and the Environment.” In order to ascertain the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used, which measures the internal consistency or reliability of a set of research elements. The analysis showed that the questionnaire has an acceptable level of reliability (α = 0.909).

4.4. Data Collection

Data were collected over a 3-months period and more specifically from 03/11/2022 to 17/02/2023. The questionnaire created for the purposes of the research was sent to all 7 Health Districts of the country, as well as to private employees of the healthcare sector from the close environment of the researchers, so that there would be a relative representativeness and in order to make possible the comparative evaluation of the health structures from different regions of Greece and also between the public and private sectors in terms of their attitude towards climate change. For the public sector a link was sent electronically to all Health Districts via Google Forms and the reason why the research was extended to all the Health Districts, is because in Greek studies that studied energy consumption as well as the management of infectious agents, significant differences were recorded based on the region of the hospitals [

42,

43]. It is crucial to point out that for the sending of the questionnaire, all the necessary approvals were obtained both from the Scientific Councils of the Hospitals and from the Scientific Councils of their Authorities (Health Districts)

4.5. Correctness - Data Completeness Check - Statistical Data Processing

Due to the nature of the questionnaire, a more extensive completion of the results using tables and frequency diagrams was preferred. After completing the questionnaires, they checked for correctness. From the correctness check which was carried out, 100% of the questionnaires were correctly completed. Then, a completeness check was conducted which revealed that 100% are completed. The processing as well as all the analyses concerning the collected data was carried out using the Statistical Program SPSS Version 26 for Windows.

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Statistics

About the results of this research, the majority of the sample consisted of women, accounting for 76.25%, while men accounted for only 23.75% of the sample. Regarding the age of the participants, the average age was 44.6 years with a standard deviation of 9.99 years. The median age was 45 years, while the mode was 42 years. The lowest recorded age was 22 years, and the highest was 67 years. As depicted, the majority of participants in the research were postgraduate degree holders (35.09%), followed by graduates of technological education (24.27%), graduates of higher education (20.6%), and graduates of secondary education (15.3%). It must be taken into consideration that the sample also included 18 individuals with a doctoral degree, accounting for 4.75%. Regarding the work sector, the majority of the sample consisted of employees in the public sector (92.08%), while only 7.92% of the participants were employed in the private sector. Concerning the Health Districts of the hospitals where the participants work, it should be emphasized that the data presented below, from the sample of 379 individuals (employed in both public and private sectors), only pertain to public health facilities. Specifically, the majority of the sample works in hospitals falling under the 1st Health District (Attica) with a percentage of 45.38%. The 2nd Health District followed with a percentage of 19.79%. Subsequently, the 6th and 5th Health Districts accounted for 12.14% and 11.35%, respectively, while smaller samples originated from the 3rd, 7th, and 4th Health Districts with percentages of 5.28%, 3.96%, and 2.11% respectively. It is worth mentioning that the majority of the sample consisted of employees in larger healthcare organizations (more than 250 employees) with a percentage of 62.01%. They were followed by small (up to 50 employees) and medium-sized organizations (up to 250 employees) with percentages of 15.04% and 14.51% respectively. Only 32 individuals from the total participants were employed in very small organizations (up to 10 employees) with a percentage of just 8.44%. Regarding the services in which the employees were engaged, the analysis revealed that the majority of the sample were administrative staff (42.5%), followed by nursing services staff (32.7%). Medical services staff accounted for 20.3%, while only 17 individuals belonged to technical services with a percentage of 4.5%. The majority of the sample consisted of employees (82.32%), followed by supervisors (11.87%). There were also 22 managers, accounting for only 5.8% of the total sample.

5.2. General Statistics

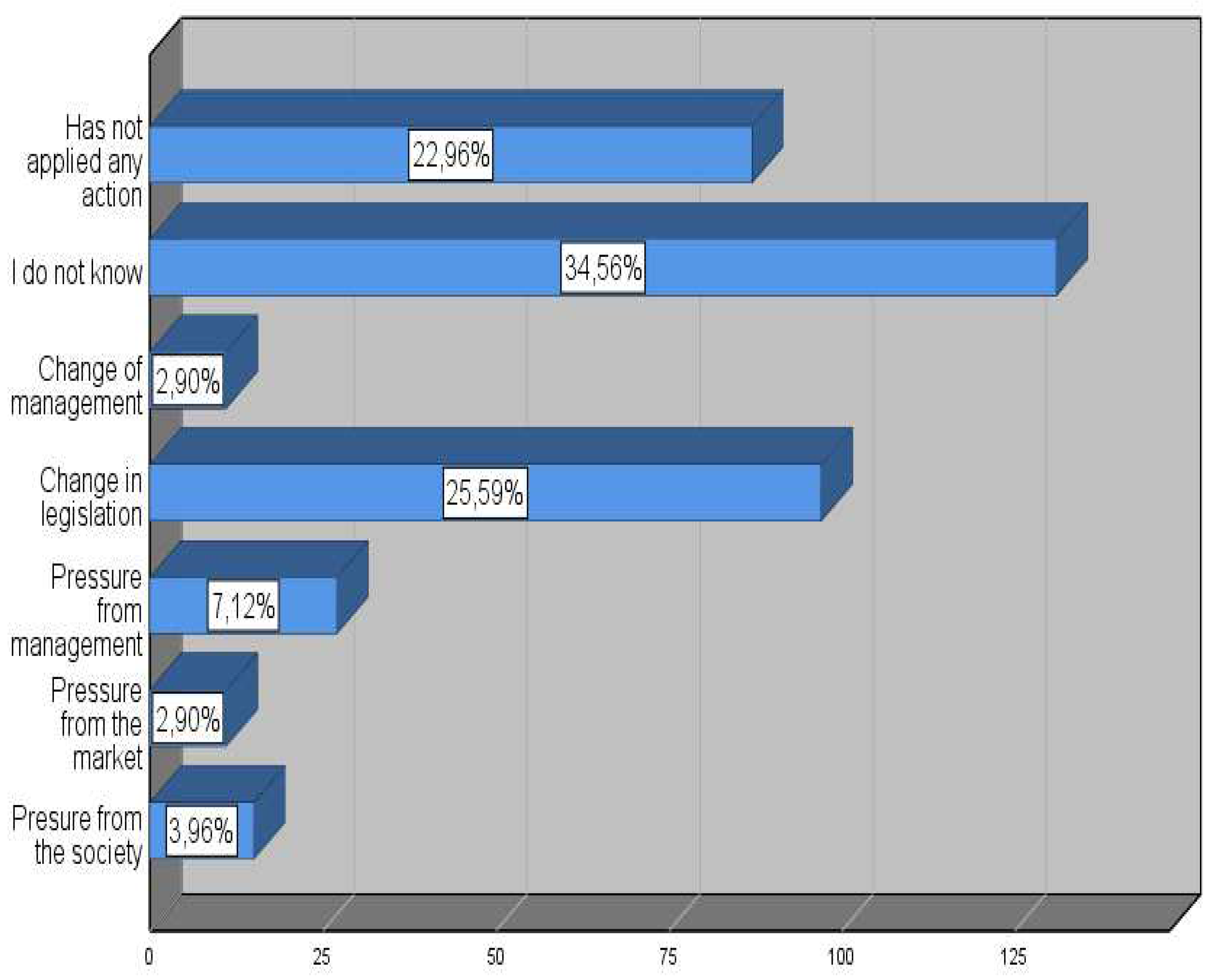

The majority of the sample (49.08%) did not know whether their organization considers the potential risks of climate change in its operational planning. Only a 27.97% stated that their organization takes into account the risks of climate change and potential environmental changes in its operational planning. Additionally, there were 87 responses, accounting for 22.96%, where participants stated that their organization does not consider anything related to climate and the environment in its operational planning. Furthermore, when participants were asked whether their organization allocates funds for climate-related actions, the majority of the sample (53.83%) did not know to answer. An equally significant percentage stated that their organization does not allocate resources to actions related to the environment and climate change (33.25%), while only 49 individuals, accounting for 12.93%, reported that their organization allocates a portion of its budget to measures for climate change and environmental protection. Regarding the factors that affected organizations in taking measures and implementing actions to address climate change and environmental changes (

Figure 1), 131 individuals (34.56%) stated that they did not know the factor that affected their organization’s change in taking measures and actions for environmental protection and climate change. 87 individuals (22.96%) responded that their organization has not implemented any actions. The analysis shows that the change in legislation (25.59%) appears to have had a significant impact on healthcare units, as it led the management of organizations to implement measures and actions for environmental protection. To a lesser extent, pressure from management (7.12%) and pressure from society (3.96%) influenced the decision-making process. The lowest level of influence was recorded for pressure from the market and change in management, both with a percentage of 2.9%.

As indicated in

Table 1, the mean value regarding the incentives for climate change actions is 2.63, with a standard deviation of 0.837. Based on these data, it can reasonably be deduced that there was no significant alignment between the organization’s values and those of its personnel. This observation is also reflected in questions related to whether the organization actively encourages employees to operate within the framework of “green behavior” and consider the environmental impact of their actions in their work. Specifically, it suggests that individuals in positions of responsibility do not motivate their subordinates to adopt environmentally friendly practices, which consequently leads to a lack of effort in educating and informing personnel about environmental issues. Furthermore, it reveals a difficulty among employees in expressing their environmental concerns. Moreover, the above finding indicates a striking lack of commitment from the personnel towards the organization’s environmental strategies and reflects a lack of enthusiasm regarding collective participation in the organization’s environmental mission. It should be noted that the aforementioned mean value represents a new variable, which is the average of the majority of questions within the section “Incentives for Climate Change Actions.” The evaluation of these specific questions was conducted using a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree 1 – Strongly Agree 5) and (Not at all 1 – Very much 5).

According to

Table 2, the mean value for the variable “Personal Attitudes towards Climate” was 2.55, with a standard deviation of 0.948. This indicates that employees do not make significant efforts to incorporate environmentally friendly actions while in their workplace. Furthermore, this analysis reveals that it is rare for employees to take actions that create a positive image for their organization. It also implies a weak willingness among employees to voluntarily and proactively engage in developing actions and taking necessary steps to operate in a more environmentally friendly manner, aiming to reduce their impact on the environment during their work. It should be pointed out that the aforementioned mean value represents a new variable, which is the average of the majority of questions within the section “Personal Attitudes towards Climate.” The evaluation of these specific questions was conducted using a five-point Likert scale (Never 1 – Always 5).

At this point, it is crucial to be mentioned that the majority of respondents have not attended any course or seminar related to climate change or environmental management (66.75%), while the remaining 126 individuals have attended something related to these issues, corresponding to a percentage of 33.25% of the total sample. Furthermore, it is emphasized that the majority of respondents seem to be conscious of the actions and measures taken at the European and national levels, with a percentage of 55.15%, while 170 individuals state that they are unaware of the measures and actions taken by central governing bodies, corresponding to a percentage of 44.85%.

5.3. Private and Public Healthcare Organizations Comparison

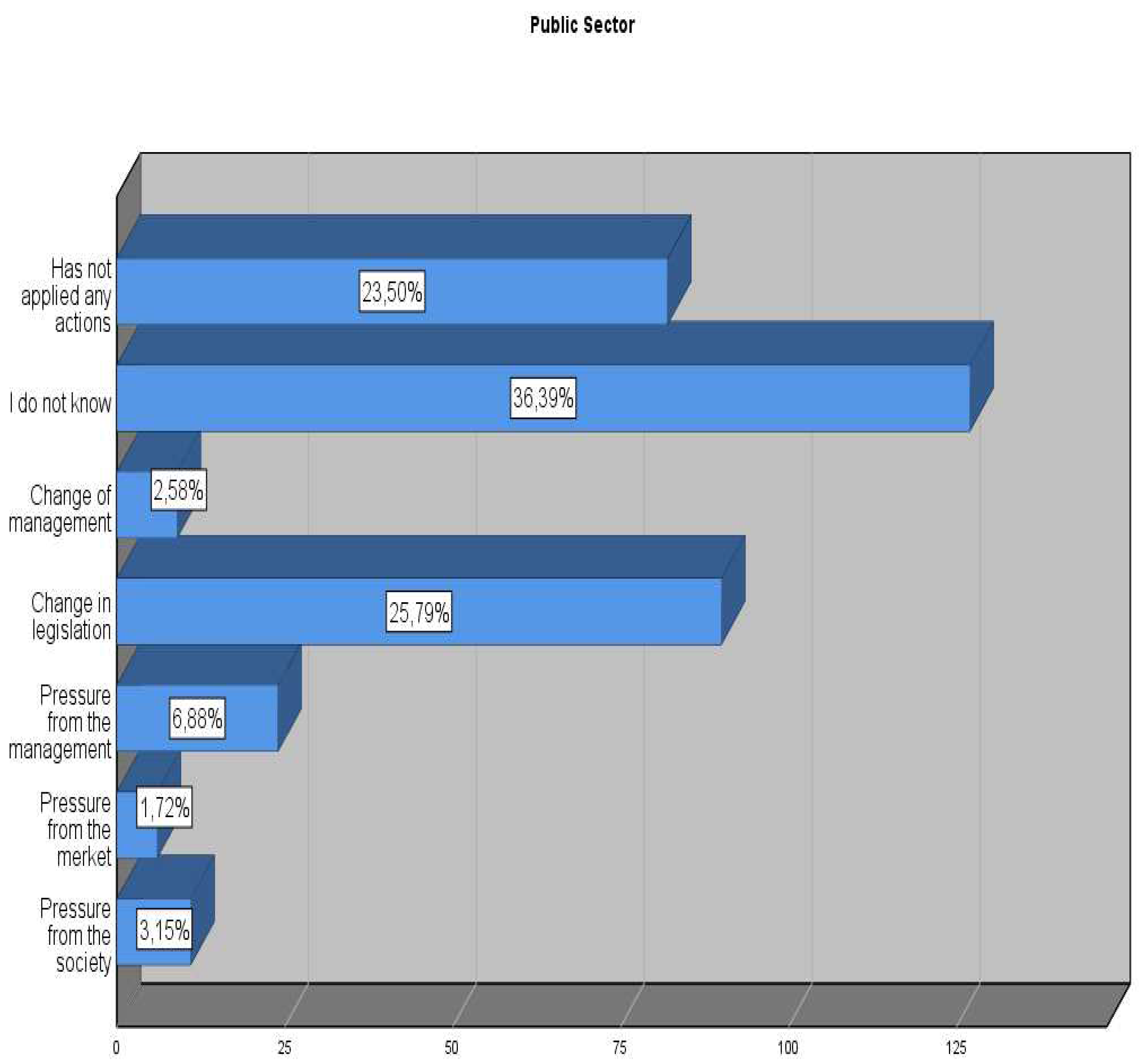

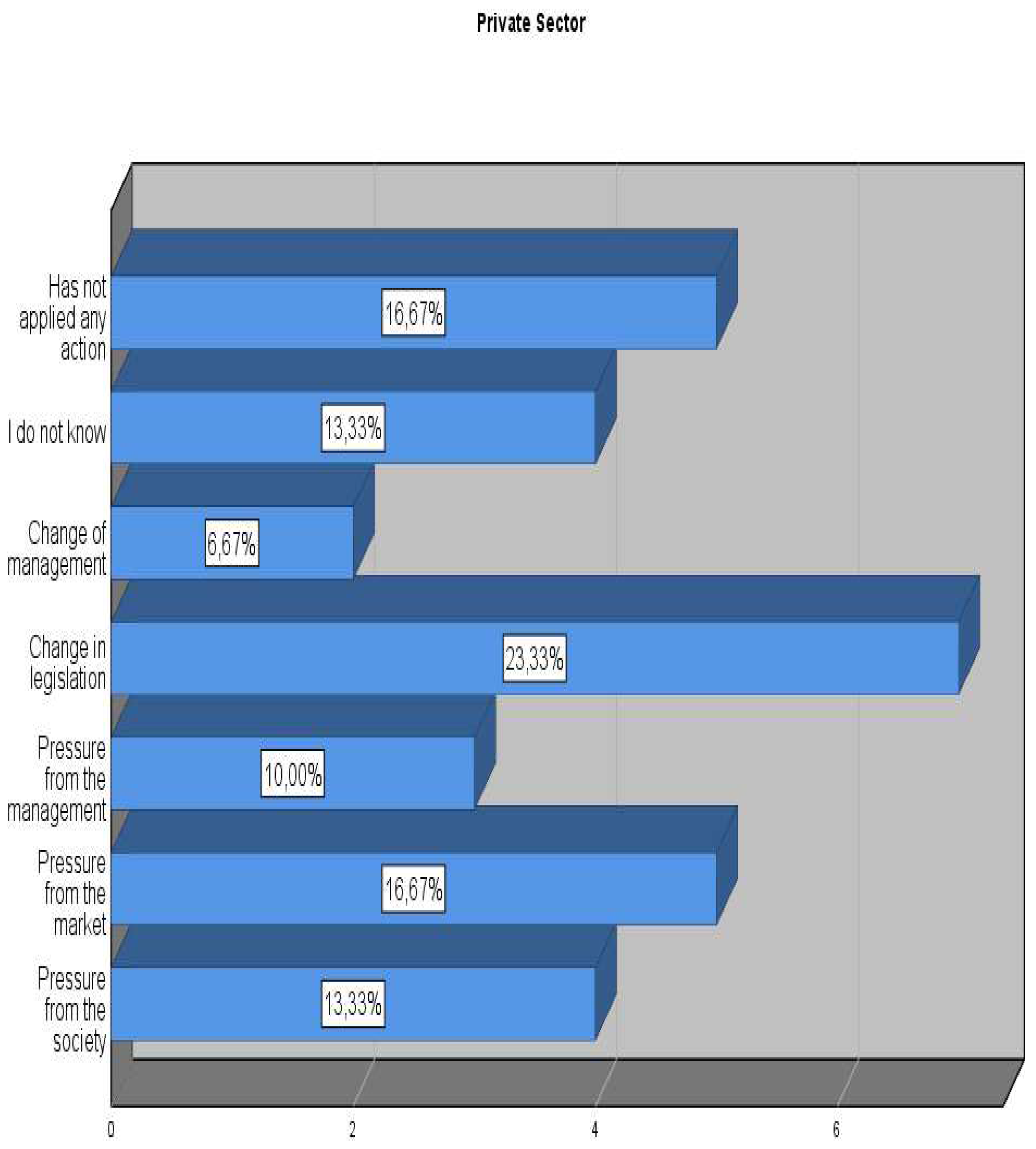

Comparing the private and public sectors regarding the factors that have influenced the adoption of climate change actions in recent years (

Figure 2,3), it was observed that in the public sector, the majority of respondents were unaware, with a percentage of 36.39%, while the corresponding percentage in the private sector was 13.33%. In both cases, the change in legislation appears to have played a significant role, as it accounted for 25.79% in the public sector and 23.33% in the private sector. A large percentage of respondents also showed that their organizations have not taken measures to address climate change, with percentages of 23.5% in the private sector and 16.67% in the public sector. Furthermore, it was noticed that the change in management had a more considerable impact in the private sector, whereas it had a lesser influence in the public sector, with respective percentages of 6.67% and 2.58%. Finally, in the private sector, both pressure from management (10%), the market (16.67%), and society (13.33%) played a significant role in the implementation of climate change policies and actions. However, it seems that these factors did not have the same effectiveness in the public sector, with percentages of 6.86%, 1.72%, and 3.15%, respectively.

Furthermore, according to

Table 3, it is observed that the majority of participants from the public sector also do not appear to know whether their organization is concerned about the impact and potential risks of climate change and includes them in its operational planning. It is worth noting that 96 participants (27.5%) stated that their organization incorporates climate change threats into its operational planning, while the remaining 78 (22.3%) answered that their organization does not take into account the potential risks of climate change in their operational planning. In the private sector, a similar balance is observed (as in the previous table) with the responses being divided. Specifically, 11 individuals (36.6%) responded that they do not know if climate change risks are included in their operational planning, 10 individuals (33.3%) stated that they are included, while the remaining 9 individuals (30%) stated that their organization does not include these risks in its operational planning.

Regarding whether the organization in which they work dedicates funds intended for climate measures and actions, the public sector again displays a great ignorance as 193 of the participants (55.3%) do not seem to know whether resources have been given for such actions, the remaining 109 (31.2%) answered that no funds have been dedicated while only 47 people (13.4%) stated that efforts have been made to finance climate measures and actions. Correspondingly, in the private sector, 17 people (56.6%) stated that their organization has not proceeded to commit funds for climate-related actions, while at the same time 11 people (36.6%) answered that they do not know whether there has been any provision for funds for such actions. It is emphasized that only 2 people (6.8%) stated that their organization allocates funds for climate measures and actions (

Table 4).

5.4. Health Districts Comparison

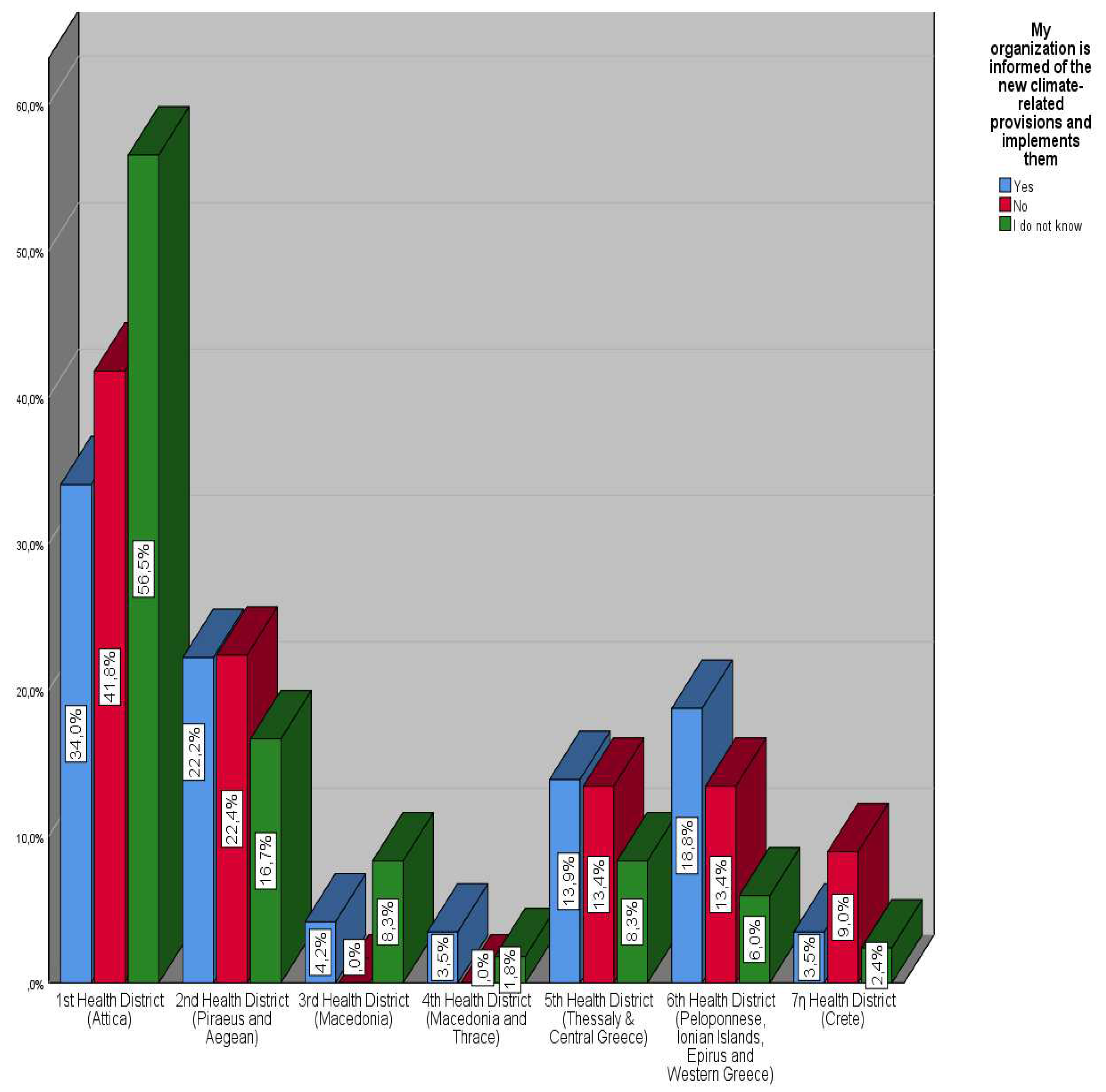

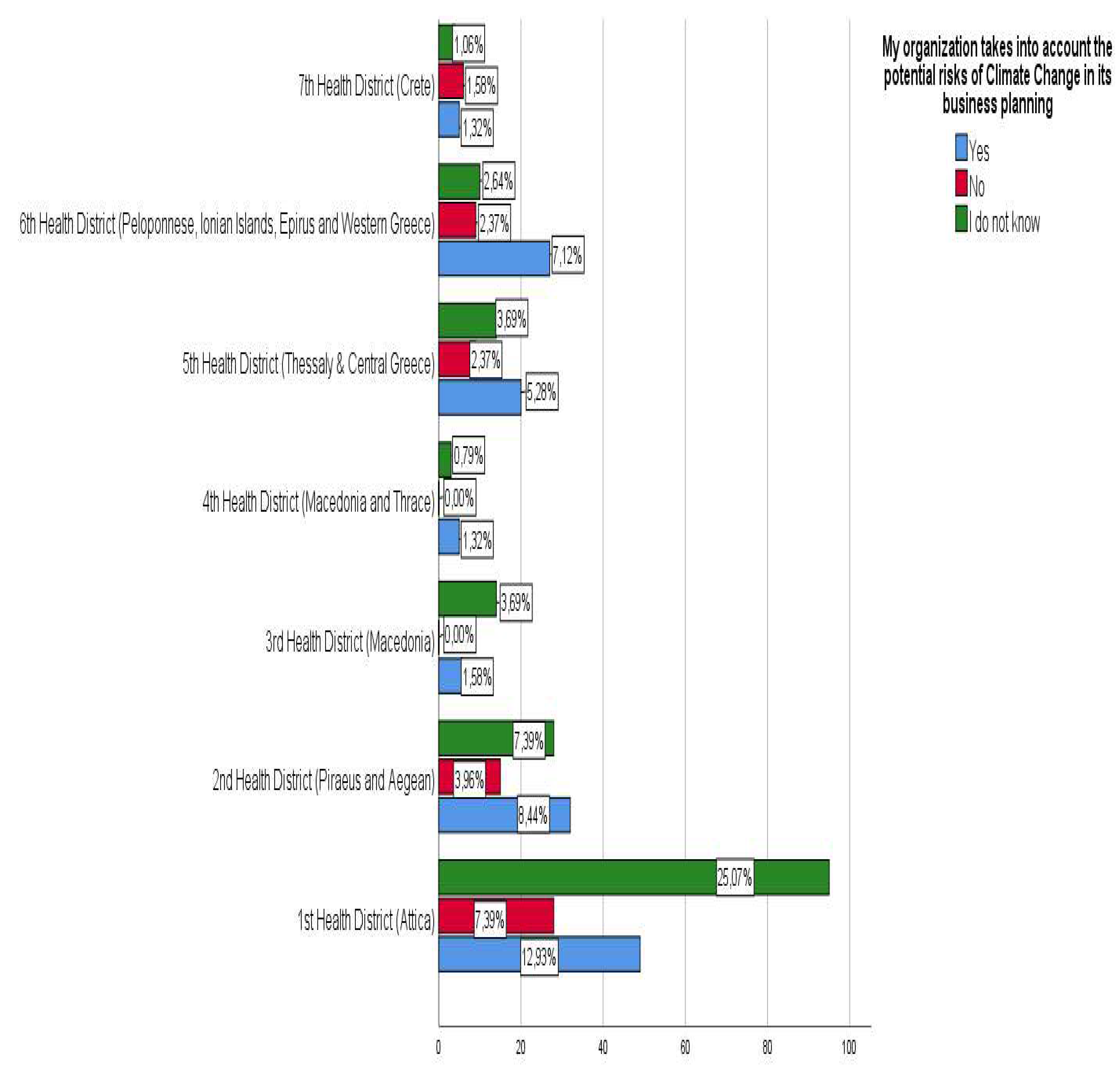

As indicated in the diagram below (

Figure 4), a large percentage of participants from the 7 Health Districts did not know how to respond regarding whether their organization is informed and implements the new regulations imposed by legislation regarding measures and actions for climate change and environmental protection. Specifically, in the 1st Health District, 95 individuals did not know how to respond, while 28 answered negatively. Only 49 individuals stated that their organizations are informed. From the sample collected from the 2nd Health District, it emerged that 32 individuals responded positively, while only 15 stated that their organization is not informed about the new environmental regulations. Additionally, 28 participants did not know how to answer. The 6th Health District had a remarkably positive response, as out of a sample of 46 individuals, the majority (27 individuals) stated that their organization is informed about the new regulations, while only 19 individuals in total responded negatively or did not know how to answer. Regarding the 3rd Health District, in a sample of 20 individuals, the majority did not know how to respond, with only 6 participants stating that their organization takes into account the new environmental regulations. It should be indicated that none of the participants responded negatively. In the 5th Health District, out of a total of 43 participants, 20 responded positively when asked about the information their organization has about the new regulations, while the remaining 23 either did not know how to answer (14 individuals) or responded negatively (9 individuals). In the 7th District, the responses were divided, as out of a sample of 15 individuals, 10 did not know how to answer or responded negatively, while only 5 of them stated that their organization is informed about the new environmental regulations and implements them. Finally, in the 4th Health District, which had the smallest sample with only 5 individuals, 3 participants responded positively, while 3 participants did not know to how to answer.

As reflected in

Figure 5, a significant number of participants from the 7 Health Districts do not appear to be aware of whether their organization takes into account the potential risks of climate change when creating their operational plan. However, it is observed that in the majority of the 7 Health Districts, among those who didn’t know to respond, most stated that their organization incorporates threats from climate change into its operational planning, while significantly fewer answered negatively.

5.5. Comparison According Demographic Questions

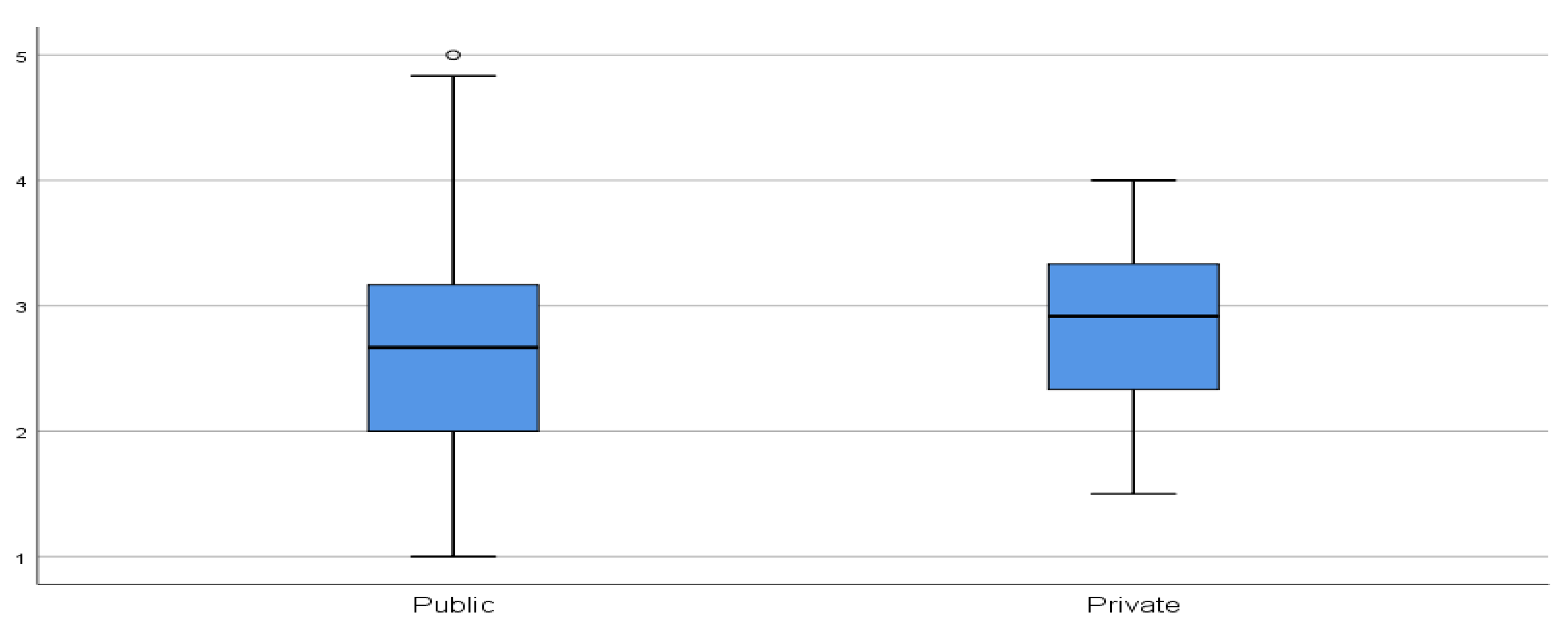

As evident from

Figure 6, the private sector exhibits a slightly higher average compared to the public sector, denoting that the encouragement and motivation of employees regarding the adoption of a more “green behavior” during their work is slightly more pronounced in the private sector.

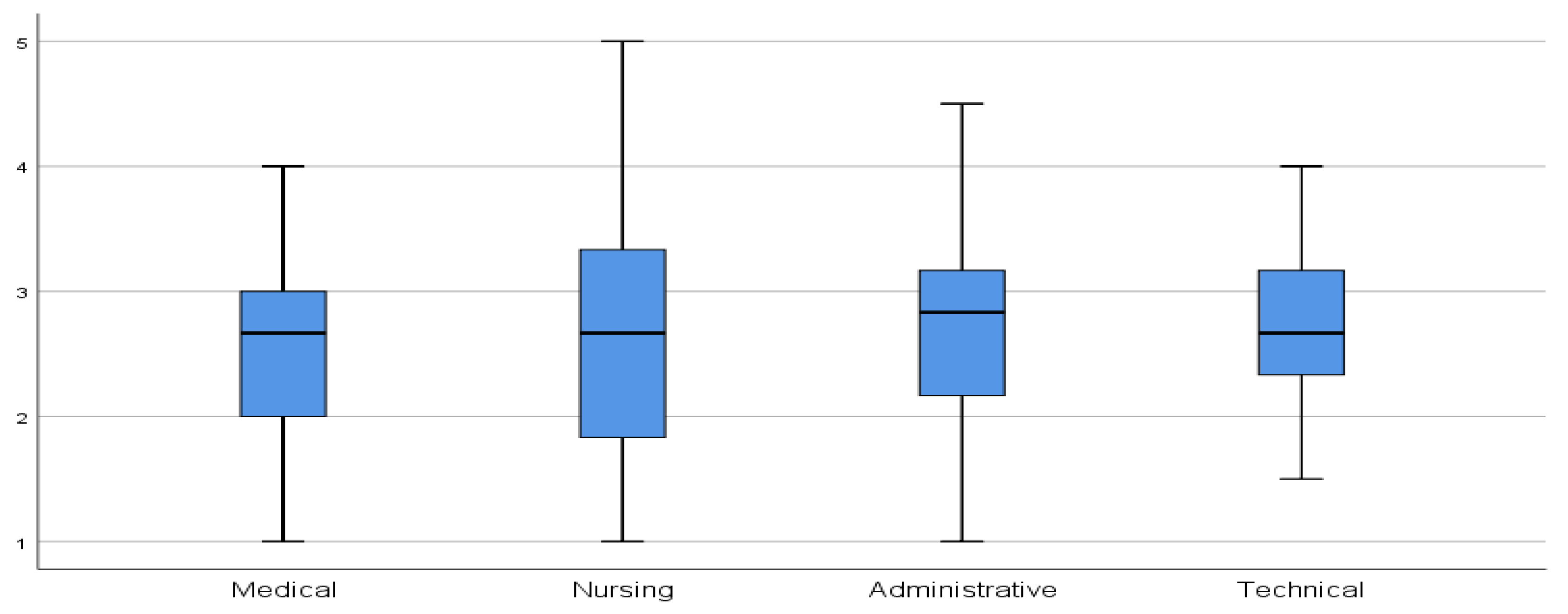

In addition, a comparison was made regarding the service in which the participants are employed (

Figure 7). The analysis showed that employees in the technical service have the highest average value, followed closely by administrative staff. Employees in the nursing service are placed next, and finally, the lowest levels of motivation are observed in the medical service. It is worth noting that although a small difference emerges among the three services (Technical, Administrative, and Nursing) in terms of motivating and encouraging employees to operate in a more environmentally friendly manner, the mean values in all cases are low, indicating that significant endeavors are not being made to promote environmentally friendly practices among healthcare workers in their daily work.

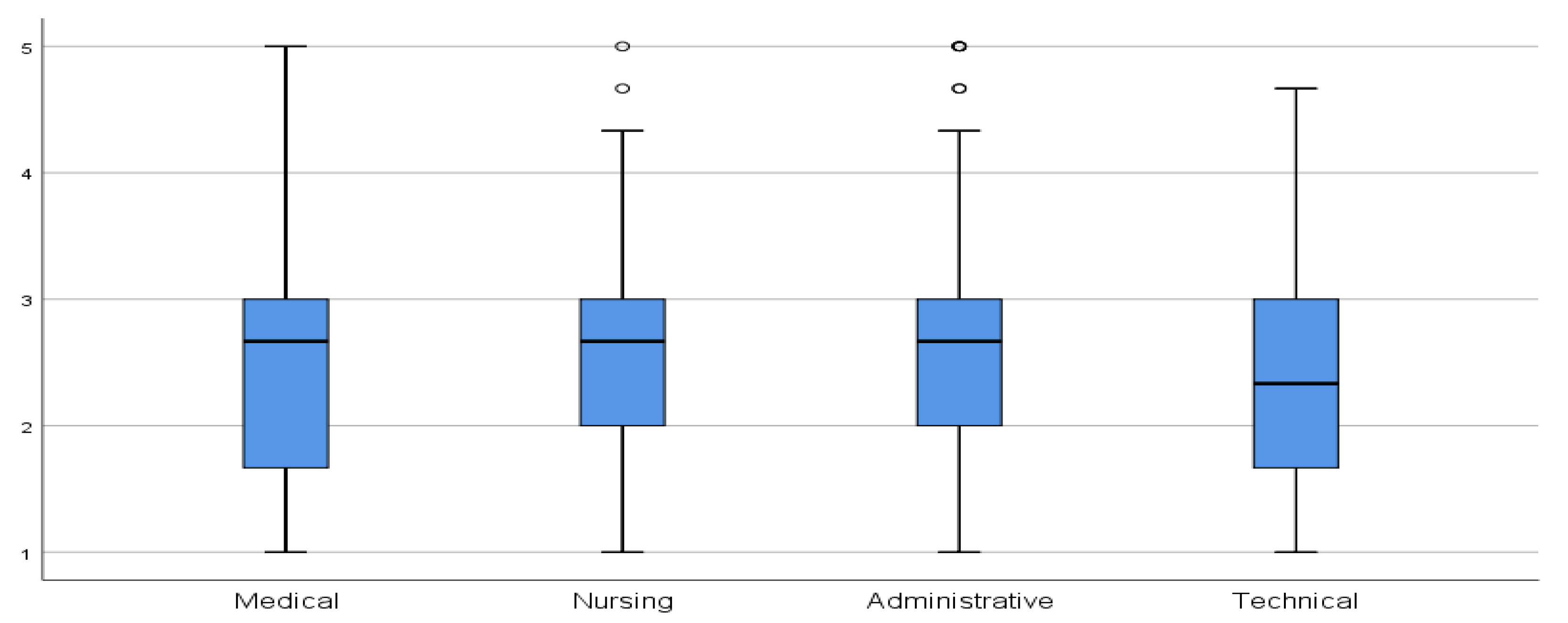

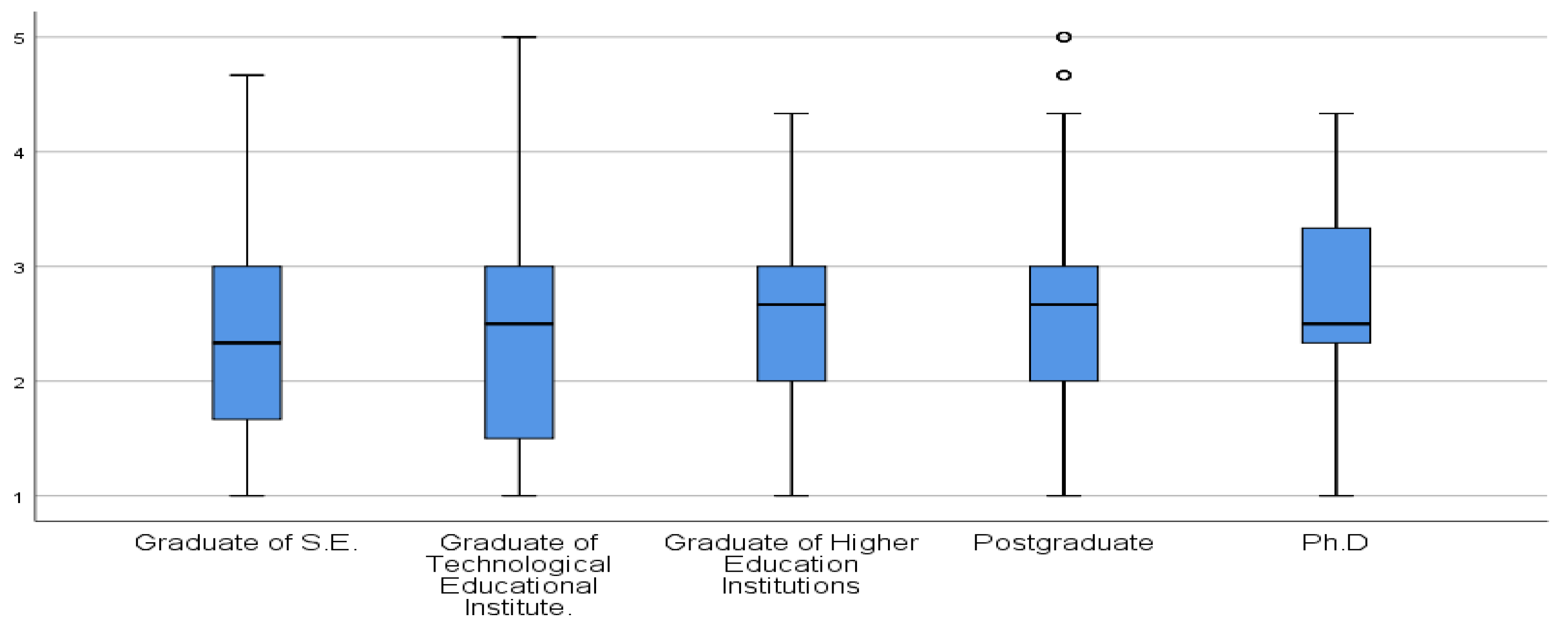

Finally, a similar analysis was conducted for the section “Personal Attitudes towards Climate” in terms of educational level and the type of service in which the participants are employed (

Figure 8 and 9). Specifically, the administrative service recorded the highest average, indicating that they tend to operate slightly «greener» compared to other services. The nursing service follows, while the technical and medical services present the lowest average values.

According to

Figure 9, it is obvious that the educational level of participants affects the degree to which they think and act “green” during their work. Participants with a doctoral degree have the highest average, followed by graduates of a master’s degree program, and then graduates of higher education institutions (university). The overall averages are not particularly encouraging, indicating a lack of intention among personnel in independent service and job positions to voluntarily engage in environmental protection efforts and operate in a more “greener” manner. This conclusion should not come as a surprise, as the data concerning employee motivation also aligns with this, indicating a particularly low level of motivation. Finally, it is worth emphasizing that the educational level appears to play a significant role in adopting actions and taking initiatives at an individual level.

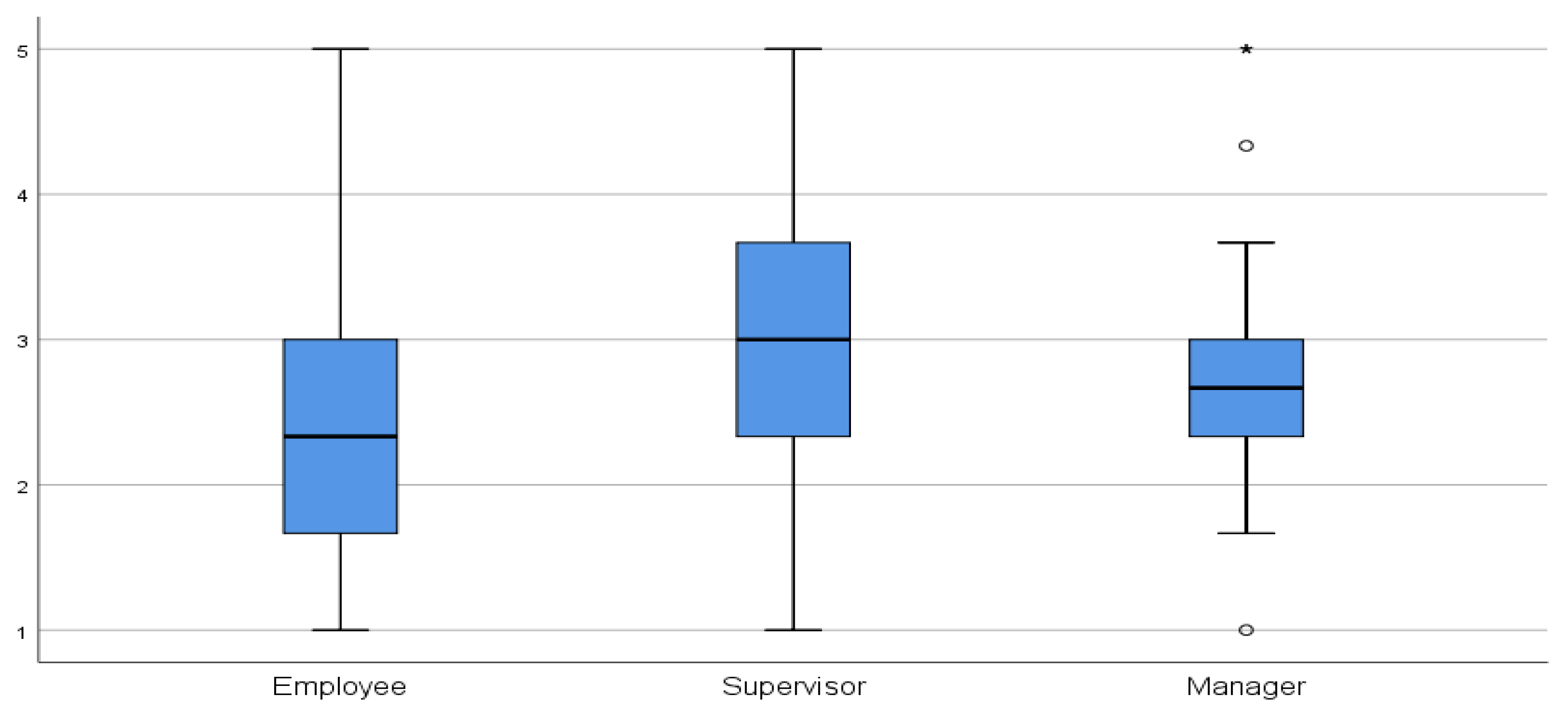

As shown in the figure above (

Figure 10), it appears that supervisors have a tendency to operate in a more “greener” manner in their work by adopting behaviors and taking initiatives to implement actions aimed at protecting the environment. Immediately following are the managers with an average level, while employees demonstrate significantly fewer initiatives and a lack of green behavior.

6. Discussion

The preceding research attempted to record the role of organizational behavior of healthcare organizations towards the impact of climate change, the extent to which their administrations motivate staff to operate in a more environmentally friendly manner during their work, while at the same time an attempt was made to record the personal perceptions of the healthcare professionals themselves. From the findings of the research, it became evident that to a large extent the health workers were not aware whether their organization takes measures and actions concerning climate-related matters, something that presents crucial challenges in terms of information dissemination and the establishment of effective communication within the organization, while at the same time the training efforts of staff on environmental issues were minimal. In particular, the administrations do not seem to include the health workers in the formulation of policies and the development of actions, something that is particularly evident from the fact that the employees presented a moderate identification of values with their organizations. Especially noteworthy is the apparent exclusion of health workers from policy formulation and action development by the administrations, something that is particularly evident from the fact that the employees presented a moderate identification of values with their organizations. The aforementioned findings diverge from the existing literature, as the relevant reports emphasize the necessity of quality communication and valid and timely dissemination of information to employees as it is a fundamental tool for conveying the vision, ideas and principles of management to others. Furthermore, the fact that the staff’s ability to take some relevant initiative for some green action is particularly low, in correlation with the low levels of commitment in the organization leads to the absence of their participation in environmental strategies as in this way a rupture is created in the relationship between employee and organization. The absence of staff training and personnel briefing, the non-participation of employees in decision-making, as well as the fact that there is no information about the actions and policies that the organization is going to adopt, lead to the discouragement of health workers from voluntarily adopting green actions while at the same time making efforts to create a common vision almost impossible, thus leaving zero chances of achieving any environmental policy or action. At this point, once again, the findings diverge significantly from the relevant literature, as there seems to be no evidence of administrations making an effort to give a more active role to their employees, to develop educational programs and informative seminars on environmental issues, and to attempt to motivate employees through rewarding their voluntary actions. Comparing the above analysis with the relevant researches that have been carried out abroad, the huge gap that exists between the health organizations in Greece and in other countries at the European and international level is clearly visible in terms of the value given to the opinion of health workers and also in the more general approach to environmental issues. Speaking more specifically, in the case of the Veterans Health Administration, the value of communication as well as the value given to employees as factors in the creation of a common environmental vision and the success of green policies emerge strongly, something in which, as developed above, Greece lags significantly. Furthermore, a strong differentiation is observed in terms of the personal perceptions of health workers as in Greece low or moderate recognition of the effects of climate change on health is recorded, while in a related study for countries at international and European level high or moderate recognition is found in the majority of cases. A small comparison between the private and public sectors did not show significant differences in most cases. More specifically in public sector organizations, changes in legislation seem to have played an important role in the implementation of climate actions, while, in the private sector, beyond the legislation, which in this case was the main influencing factor, other factors such as pressure from society, the market, and management also played a significant role. In a corresponding analysis conducted by the Health Regions, it was observed that climate change is taken into account in all the Health Regions but to a particularly low extent. In terms of staff motivation and training, the private sector appears to prevail over the public sector, while in the same analysis the medical service lags significantly behind the other three, with the administrative service recording the highest degree of staff motivation and training. Furthermore, supervisors seem to act “greener” by adopting behaviors and initiatives to implement environmental protection actions, while the corresponding levels for employees are clearly lower, which is consistent with the fact that there is a lack of corresponding motivation from the highest management levels. Regarding the areas of work, administrative employees appear to slightly adopt more actions and initiatives, which is consistent with the finding that the administrative department also records the highest degree of employee motivation. Finally, the level of education significantly affects the adoption of voluntary green actions, as the higher the level of education, the more environmentally aware individuals operate. During the conduct of the research, some important limitations emerged. Time was clearly a significant constraint, while another limitation was the relatively small representativeness taking into account the large sample deviations between the two sectors (public and private), between the 7 Health Regions and also the fact that the overall sample was relatively small in comparison with the total population of the research.

7. Conclusions

This specific research highlights the necessity of adopting and implementing policies and actions in health organizations in Greece. Studying Greek data simultaneously with relevant research from abroad, a significant gap becomes apparent, not only in understanding the impact of climate change but also in addressing it by healthcare organizations, among Greek healthcare organizations and those of other countries. This rings the alarm bell of danger to the country’s government authorities, hospital administrations as well as their staff, as it highlights the urgent need for practical implementation and formulation of green policies in Greek health organizations in order to bridge the gap and achieve compliance global sustainability standards. As the world faces increasing challenges from climate change and resource scarcity, health organizations are expected to play a key role in addressing environmental consequences. Through the adoption of sustainable practices, the environmental footprint of organizations is not only improved, but also their overall effectiveness and sustainability in the long term is also enhanced. Also, through the research, several key factors were indicated that account for the gap between Greece and other countries in terms of sustainable policies and actions. A major issue is the lack of a coherent regulatory framework that mandates and encourages sustainable health practices. With many countries having already created credible policies, creating a clear path for health organizations to adopt sustainable measures, Greece seems to have been late in developing such policies, leading to a haphazard approach to the issue. Furthermore, the research findings accentuate the significance of Organizational Behavior and the integration of its principles within healthcare organizations for the successful execution of sustainable policies. In particular, leadership commitment, employee involvement and overall organizational culture significantly influence the successful implementation of sustainable policies. Unfortunately, in Greece, the existing organizational behavior tends to prioritize immediate economic benefits over long-term sustainability benefits. This short-term approach prevents the integration of sustainable practices into the core values and day-to-day operations of healthcare organizations. In order to address these challenges and bridge the gap, it is essential for Greek healthcare organizations to prioritize sustainability as their core value. This change requires active participation from government bodies, leaders and workers. First of all, the Greek government must develop and enforce a coherent regulatory framework which will oblige health organizations to adopt sustainable policies and actions. By providing clear guidelines and incentives, the government can encourage the integration of sustainability into the core of the health sector. Secondly, in Greece, the leaders of health organizations must pave the way for promoting sustainability by showcasing a steadfast commitment to environmental practices. This includes investing in green technologies, promoting responsible waste management and adopting measures to save energy. Leaders must communicate the importance of sustainability to all employees and encourage them to participate in decision-making processes, promoting a culture of collective responsibility. Furthermore, Greek healthcare organizations must emphasize the training and development of their employees to comprehend and address issues related to sustainability. This can enhance the capabilities and awareness of employees on issues related to environmental protection and sustainable development. By fostering a workforce that is knowledgeable about sustainable practices, these organizations can foster innovation and creativity in the intensively localized sector. Finally, cooperation between Greek health organizations and international partners can be useful in bridging the gap. Through friction with more sustainable health systems of other countries, valuable insights and best practices can be gained. Participation in international forums and collaborations can facilitate the exchange of knowledge and expertise on sustainability, allowing Greek health organizations to take important steps to close the gap. In summary, by prioritizing sustainability as a core value, involving all stakeholders and learning from international sources, Greek healthcare organizations can lead the sector towards a greener and more sustainable future.

References

- Kazdin, A. E. Psychological science’s contributions to a sustainable environment: Extending our reach to a grand challenge of society. Am. Psychol 2009, 64, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P. C. Contributions of psychology to limiting climate change. Am. Psychol 2011, 66(4), 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swim, J. K.; Stern, P. C.; Doherty, T. J.; Clayton, S.; Reser, J. P.; Weber, E. U.; Gifford, R.; Howard, G. S. Psychology’s contributions to understanding and addressing global climate change. Am. Psychol 2011, 66, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daily, B. F.; Bishop, J.W.; Govindarajulu, N. A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Bus Soc. 2009, 48, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P. J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N. J. R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.; Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J. I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Economic losses from climate-related extremes in Europe (8th EAP). Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/economic-losses-from-climate-related (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Environment, climate change and health in relation to Universal Health Coverage Environmental protection and climate change mitigation can improve human health and alleviate pressure on health care systems. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/environment--climate-change-and-health-in-relation-to-universal-health-coverage (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global spending on health: rising to the pandemic’s challenges. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064911 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global spending on health: Weathering the storm. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017788 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Mostepaniuk, A.; Akalin, T.; Parish, M. Practices Pursuing the Sustainability of A Healthcare Organization: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (n.d.). Everyone Included: Social Impact of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/everyone-included-covid-19.html (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- United Nations Development Programme. Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.undp.org/coronavirus/socio-economic-impact-covid-19 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Livelihoods, Their Health and Our Food Systems. Available online: https://pmnch.who.int/resources/publications/m/item/impact-of-covid-19-on-people-s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Grazhevska, N.; Mostepaniuk, A. The Development of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Context of Overcoming a Welfare State Crisis: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Comp. Econ. Res. 2021, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flogaiti, E. Education for the environment and sustainability, Greek Letters, Athens, Greece, 2011; ISBN 978-96-0955-226-4.

- Merlina, M.; Karl-Henrik, R.; Göran, B. A strategic approach to social sustainability: A principle-based definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017; 140, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Do environmental management systems improve business performance in an international setting? J. Int. Manag 2008, 14, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, M. (2017). Towards Sustainable Health Care Organizations. MDKE 2017, 5(3). 377-394. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Gazzola, P. Aesthetics and Ethics of the Sustainable Organizations. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 9, 291-301. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/328023987.pdf.

- Abid, G.; Contreras, F. Mapping thriving at work as a growing concept: review and directions for future studies. Information 2022, 13, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Contreras, F.; Rank, S.; Ilyas, S. Sustainable leadership and wellbeing of healthcare personnel: A sequential mediation model of procedural knowledge and compassion. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1039456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, J. T.; Holt, R. A. Defining sustainable leadership. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2010, 2(2), 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A. E.; Dayan, M.; Di Benedetto, A. New product development team intelligence: antecedents and consequences. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, A. R.; Hughes, L.; Fern, L. A.; Monaghan, L.; Hannon, B.; Waters, A.; Taylor, R.M. Healthcare staff well-being and use of support services during COVID-19: a UK perspective. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 34, e100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, L. J. Management and Organizational Behavior, 11th ed.; Trans-Atlantic Publications: Philadelphia, PHL, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-12-9208-848-8. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A.; Campbell, T.T. Organizational Behavior, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-12-9201-655-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. M.; Lee, D. Developing Green Healthcare Activities in the Total Quality Management Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budgett, A.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Schneller, E. Procurement in Public & Private Hospitals in Australia and Costa Rica—A Comparative Case Study. Health Systems 2017, 6(1), 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ιandolo, F.; Vito, P.; Fulco, I.; Loia, F. From Health Technology Assessment to Health Technology Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Care Without Harm. The Global Green and Healthy Hospitals Agenda. Available online: https://noharm-global.org/issues/global/global-green-and-healthy-hospitals-agenda (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Moldovan, F.; Blaga, P.; Moldovan, L.; Bataga, T. An Innovative Framework for Sustainable Development in Healthcare: The Human Rights Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tooranloo, H. S.; Karimi, S.; Vaziri, K. Analysis of the Factors Affecting Sustainable Electronic Supply Chains in Healthcare Centers: An Interpretive-Structural Modeling Approach. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 31, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Hospitals, Healthy Planet, Healthy People. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/healthy-hospitals-healthy-planet-healthy-people (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Azar, F.Ε.; Farzianpour, F.; Foroushani, A.R.; Badpa, Μ.; Azmal, M. Evaluation of Green Hospital Dimensions in Teaching and Private Hospitals Covered by Tehran University of Medical Sciences. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Greenhealth. Sustainability Solutions for Health Care. Available online: https://practicegreenhealth.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Renee, N. S. The increasing connection between climate change and health. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2022, 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration. Available online: https://www.va.gov/health/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Green Environmental Management System (GEMS). Available online: https://www.va.gov/maryland-health-care/programs/green-environmental-management-system-gems/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Bakhsh Magsi, H.; Ong, T. S.; Ho, J. A.; Sheikh Hassan, A.F. Organizational Culture and Environmental Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepetis, A.; Zaza, P. N.; Rizos, F.; Bagos, P.G. Identifying and Predicting Healthcare Waste Management Costs for an Optimal Sustainable Management System: Evidence from the Greek Public Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaza, P. N.; Sepetis, A.; Bagos, P. G. Prediction and Optimization of the Cost of Energy Resources in Greek Public Hospitals. Energies 2022, 15, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).