1. Introduction

The caregiver burden is a response to the numerous problems and challenges faced by individuals caring for a sick loved one [

1,

2]. This burden is considered a combination of both the objective aspects of caregiving, including the time and physical demands of care, as well as subjective experiences such as emotional perceptions secondary to individual care [

3,

4].

This phenomenon was initially described in 1980 by Zarit and colleagues in the medical field, particularly when associated with chronic and terminal illnesses such as cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and stroke [

2]. These researchers developed a 22-question questionnaire to assess this burden, known as the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI).

In 2017, Spitznagel and colleagues evaluated this burden and the psychosocial function of pet owners of sick animals through a modified ZBI for pet caregivers—an 18-item questionnaire graded on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). A total score above 18 on the modified ZBI is considered indicative of a clinically significant burden. The results showed increased burden, stress, and symptoms of depression/anxiety, as well as poorer quality of life in caregivers of animals with chronic or terminal illness. The higher burden was correlated with reduced psychosocial function, i.e., emotional and social impairment of these caregivers [

4].

The findings from Belshaw et al. [

5] and Spitznagel et al. [

6] shed light on the caregiver burden experienced by owners of dogs diagnosed with osteoarthritis. Belshaw et al. revealed that owners faced heightened worry and concern due to factors such as veterinary visits, challenges in finding effective treatments, and managing their dog’s medication and weight. Negative consequences, including physical health issues like back pain, were reported. Despite these challenges, owners expressed enduring love and devotion, emphasizing the emotional support provided by their dogs in times of stress and life changes. Spitznagel et al. suggested that owner satisfaction with treatment and the veterinary healthcare team played a protective role against caregiver burden, influencing decisions related to euthanasia. Satisfactory treatment and support offset considerations of euthanasia, emphasizing the importance of addressing owner satisfaction and providing comprehensive support to mitigate caregiver burden and its potential impact on decision-making processes.

Caregiver burden experienced by owners of dogs with behavioral problems were also addressed. Buller and Ballantyne [

7] indicated consequences such as increased time for management and training, limitations on activities, and emotional challenges like sadness, frustration, and guilt. Despite a strong human-animal bond, these negative emotions could lead to social isolation. Kuntz et al. [

8] extended this understanding by demonstrating that 68.5% of owners experienced clinically meaningful caregiver burden. Older owners reported less burden, indicating age-related variations. The study also highlighted the potential burden transfer to veterinarians in behavior practices, emphasizing the need for routine evaluation to address occupational distress. Both studies underscore the complex emotional landscape of owners caring for dogs with behavioral issues, emphasizing the importance of tailored support and interventions for their well-being.

Spitznagel et al. [

9,

10] analyzed the caregiver burden experienced by owners of dogs with chronic or terminal diseases and identified signs and behaviors correlated with burden, including weakness, appearance of sadness or anxiety, pain or discomfort, and personality changes. Caregiver burden was associated with greater symptoms of depression and stress, indicating a significant impact on psychosocial function. Also, changes in routine due to the pet’s condition and the perceived difficulty of following new rules and routines for management were linked to increased caregiver burden. Recognizing caregiver burden and understanding its determinants can inform empathic responses from veterinarians, fostering better communication and potentially alleviating downstream effects, such as increased workload for veterinary professionals. In a cross-sectional observational study involving 164 owners of cats or dogs undergoing evaluation at a veterinary oncology service, the researchers found a significant correlation between caregiver burden and elevated stress, increased symptoms of depression, and lower overall quality of life. Additionally, the highest level of burden was noted when associated with certain treatment plan factors, such as changes in animal care routines, associated with the perception that adherence to treatment routines was challenging and/or a feeling of difficulty in adhering to medication routines. The authors emphasize the importance of recognizing caregiver burden in individuals caring for companion animals with cancer, even in its early stages [

11].

Dermatological diseases in pets often require long-term treatment that may contribute to caregiver burden. Considering this, Spitznagel and colleagues [

12] in 2017 assessed caregiver burden in pet owners of animals with dermatological conditions compared to owners of healthy animals and the relationship of these caregivers with quality of life. They found a correlation between caregiver burden and quality of life related to dermatological disease, indicating a higher burden in caregivers of animals with skin diseases compared to healthy animals [

12]. The findings from the 2021 study [

13] revealed a significant correlation between caregiver burden and both skin disease severity and the complexity of the treatment plan, emphasizing the importance of simplicity in treatment planning. Even after considering skin disease severity, the correlation with treatment complexity remained significant, suggesting that starting with the simplest effective treatment may reduce owner strain and improve long-term management for the dog. The 2022 study [

14] further explored the connections among caregiver burden, treatment complexity, and the veterinarian-client relationship. It supported the idea that greater treatment complexity is related to the owner’s perception of the veterinarian-client relationship through caregiver burden. The indirect relationship observed between treatment complexity and the veterinarian-client relationship implies that reducing the burden of complex treatment may foster a better working relationship between veterinarian and client, enhancing perceptions of care, compassion, and trustworthiness.

Studies on caregiver burden in cats are relatively scarce compared to those focusing on dogs. A recent study [

15] added valuable insights by examining the caregiver burden of cat owners. The study hypothesized that owners of an ill cat would experience greater caregiver burden compared to owners of a healthy cat but lower burden than owners of an ill dog. The results supported these hypotheses, revealing that owners of an ill cat, across various illnesses, indeed exhibited a greater burden than owners of a healthy cat and a somewhat lower burden than owners of an ill dog. The reasons behind this disparity are not fully clear, but the authors suggest that a potential lack of veterinary oversight in cat care may contribute to fewer caretaking requirements for cat owners. Importantly, while this difference is statistically significant, it might not have a clinically meaningful impact on interpretation. Henning et al. [

16] investigated factors associated with the quality of life (QOL) in cats with epilepsy and the burden of care in their owners. The study highlighted the crucial role of veterinarian support, emphasizing that owners who felt unsupported might be reluctant to seek veterinary care, resulting in uncontrolled seizures and increased caregiver burden. Additionally, the burden was reported to be higher in caregivers aged 18 to 34, possibly due to life-stage pressures, while older caregivers who had already established a career and settled were better equipped to provide care and experience fewer burdens.

Suspecting that the severity of the animal’s pathology may influence the occurrence of caregiver burden, it was hypothesized that the degree of burden in caregivers of animals with oncological pathology is higher than that of caregivers of animals with dermatological pathology. Therefore, the objective was to compare the burden among caregivers of patients in these two specialties.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) under the Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appreciation (CAAE) 58860122.0.0000.5149. The research was conducted through a cross-sectional study using questionnaires administered to owners of dogs and cats undergoing dermatological and oncological treatment at the institution in a veterinary hospital.

Inclusion criteria for study participation were individuals aged 18 years or older, capable of understanding and responding to the questionnaire, responsible for an animal undergoing treatment prescribed by a specialist, and present throughout the entire duration of the pet’s treatment. Participants who did not meet these criteria did not sign the Informed Consent Form (ICF), or did not complete the questionnaire in full were excluded from the study. Participation in the research was voluntary.

Demographic information about the owner was collected and included age, gender, educational level, income, the number of people living in the household, and whether they were the sole caregiver for the animal. Information about the animal, such as species (cat or dog), diagnosis, time since diagnosis, disease stabilization, and treatment duration, was also collected through a questionnaire.

The modified Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) for pet caregivers was translated and used to assess caregiver burden [

4]. A total score above 18 on the modified ZBI was considered indicative of a clinically significant burden. The questionnaires were administered in person after the animal’s consultation. Individuals who chose to participate in the study signed the ICF beforehand. After data collection, the information was compiled into tables for statistical analysis.

The sample size was calculated based on the formula for calculating sample sizes for the description of qualitative variables in a population [

17]. Thus, a minimum sample of 67 individuals in each group was obtained. Due to the diverse probability distributions of the measured variables and the presence of outliers, non-parametric methods were applied to check for differences between groups. The Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare two groups, and non-parametric Spearman correlations were calculated between specific pairs of variables. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.3 [

18].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic

A total of 193 participants completed the survey. After excluding incomplete questionnaires, 182 valid responses were obtained—50.55% (92/182) related to oncological patients and 49.45% (90/182) to dermatological patients. Concerning the species of the patients, 84.6% (154/182) were dogs, and 15.4% (28/182) were cats.

As for the caregivers, 72% (131/182) identified as female, 26.9% (49/182) as male, 0.5% (1/182) considered themselves non-binary, and 0.5% (1/182) preferred not to disclose. The majority of caregivers (67%, 122/182) reported that they did not consider their animal’s disease to be stable at that time. A significant portion of caregivers (51.6%, 94/182) were the sole individuals responsible for their animal’s treatment at home; however, this factor did not show statistical significance (p = 0.45224). In terms of the number of people residing in the same household, 11.6% (21/182) lived alone, 44.2% (80/182) lived with 1 to 2 people, 40.3% (73/182) with 3 to 4 people, and 3.9% (7/182) with more than 4 people.

Regarding education, 0.5% (1/182) of caregivers had incomplete primary education, 0.5% (1/182) completed primary education, 1.1% (2/182) had incomplete secondary education, 13.2% (24/182) completed secondary education, 16.5% (30/182) had incomplete higher education, 30.2% (55/182) completed higher education, and 37.9% (69/182) had postgraduate education. Regarding family income, 1.2% (2/182) had no family income, 0.6% (1/182) had income up to two minimum wages, 42.2% (70/182) had 2 to 4 salaries, 34.9% had 4 to 10 salaries (58/182), 13.3% had 10 to 20 salaries (22/182), and 7.6% (13/182) preferred not to disclose.

3.2. Caregiver burden

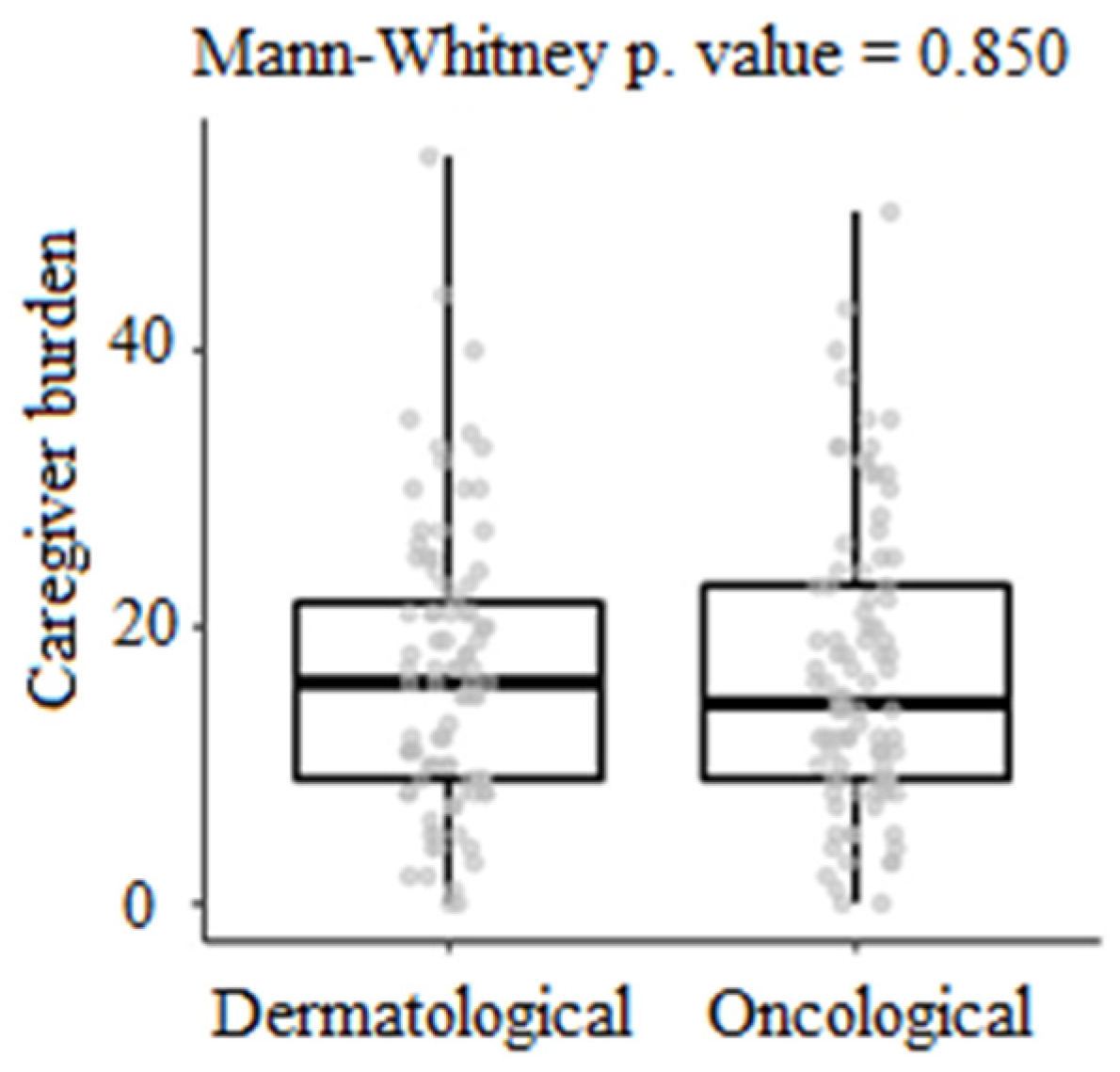

The degree of caregiver burden showed statistical differences for caregivers who reported that they did not consider their animal’s disease to be stable at that time compared to those who considered their pet’s disease to be stable (p = 0.00026). Importantly, 36.9% (34/92) of caregivers responsible for animals undergoing oncological treatment showed indications of clinically significant burden. Regarding caregivers of dermatological patients, 37.8% (34/90) scored above 18 on the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) scale. Statistically, no differences in the degree of burden were observed between the two groups (

Figure 1).

Measurements of caregiver burden and boxplot showing descriptive statistics for owners of animals with dermatological and oncological pathologies, along with their p-value

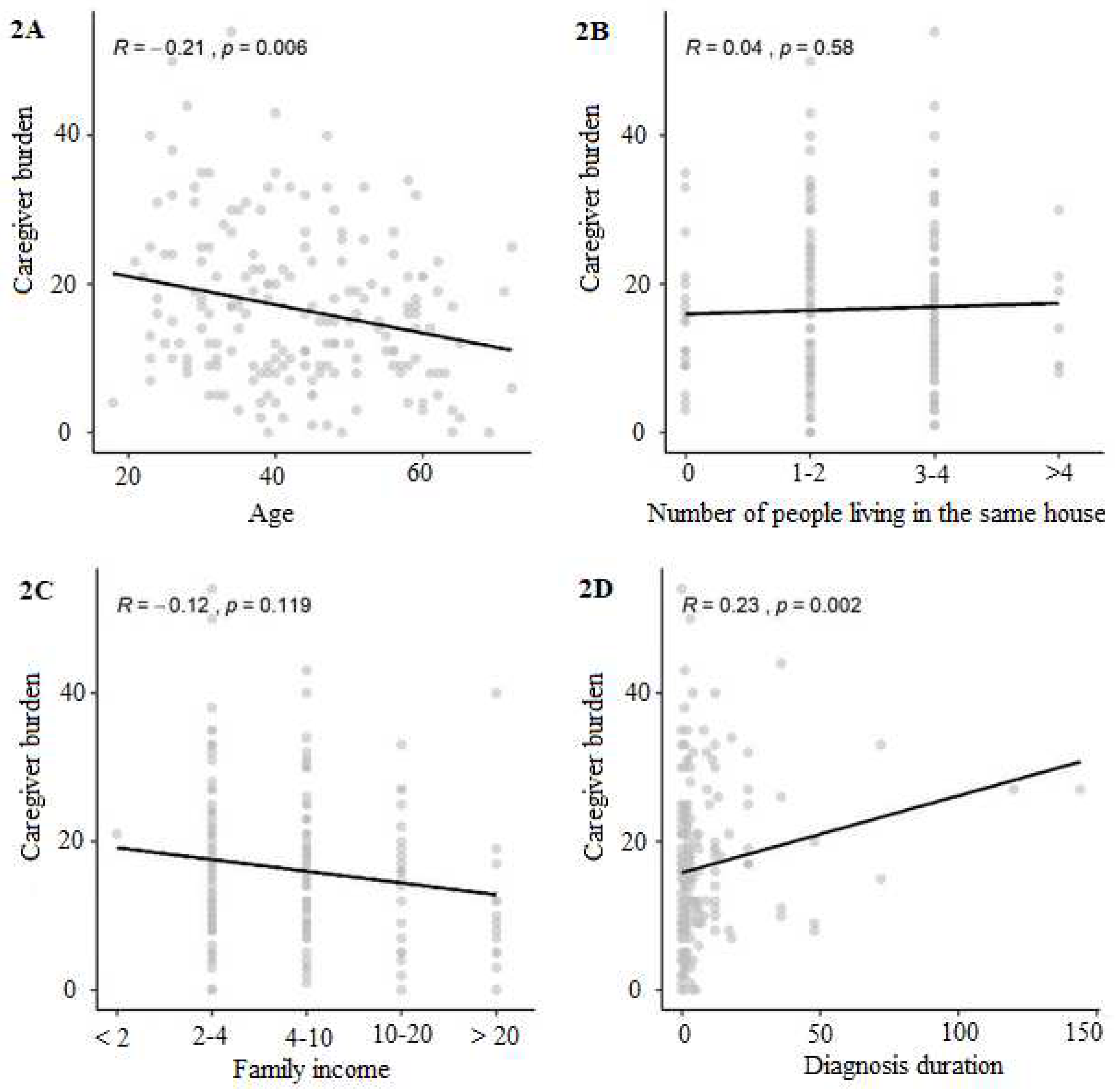

Regarding caregiver burden, 34.4% (53/154) of dog owners and 53.5% (15/28) of cat owners exhibited a significant level of burden. Statistically significant differences in the degree of burden were observed between the two groups (p = 0.01044). The correlations of caregiver burden with age, the number of people living in the same house, family income, and overall diagnosis and treatment duration are shown in

Figure 2.

Scatter analysis of caregiver burden correlated with age, number of people living in the same house, family income, diagnosis duration, and treatment duration, with Spearman correlation value, along with its p-value. for family income, follow the correspondence: group 1 (up to 2 salaries), group 2 (2 to 4 salaries), group 3 (4 to 10 salaries), group 4 (10 to 20 salaries), group 5 (more than 20 salaries).

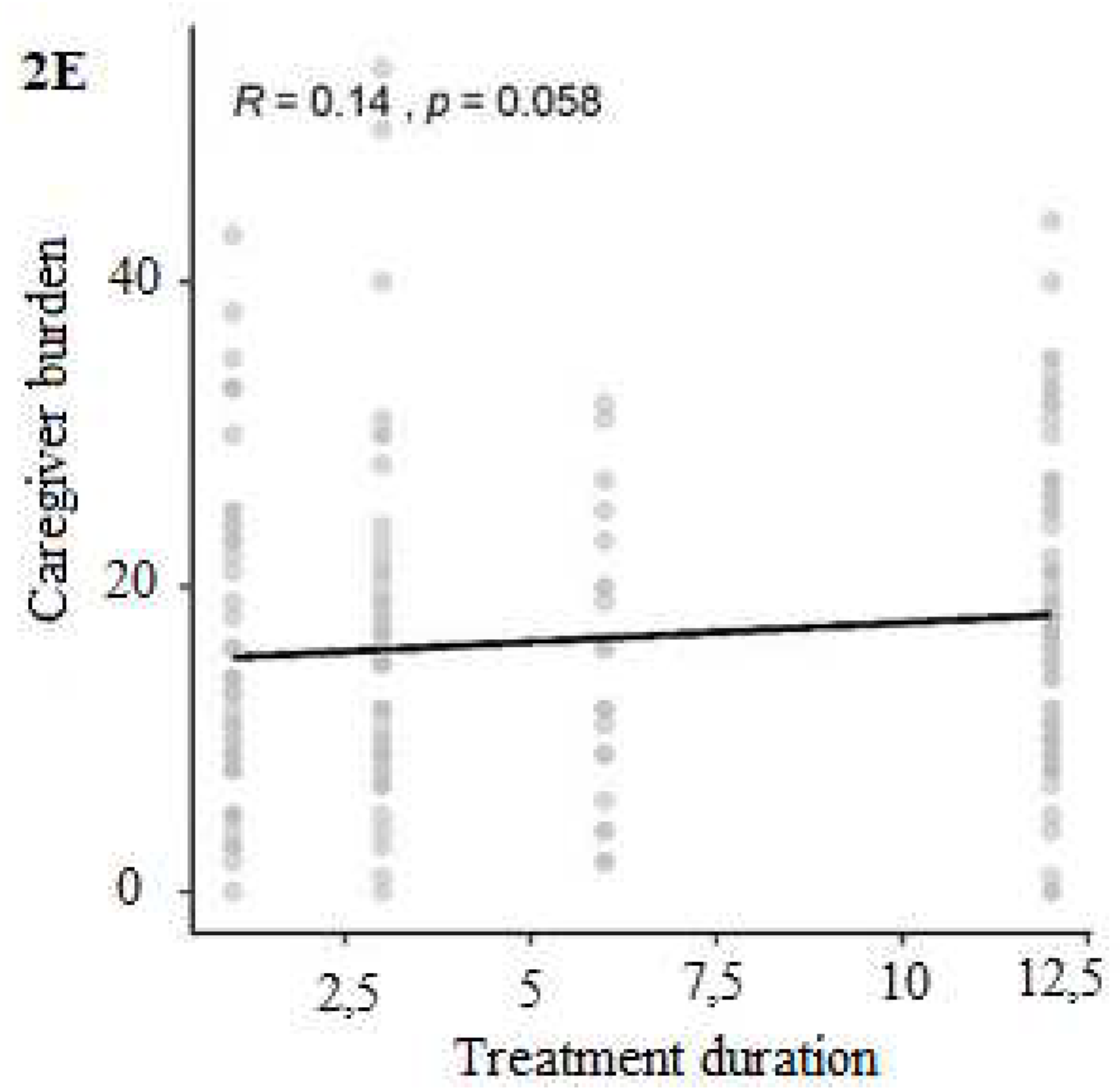

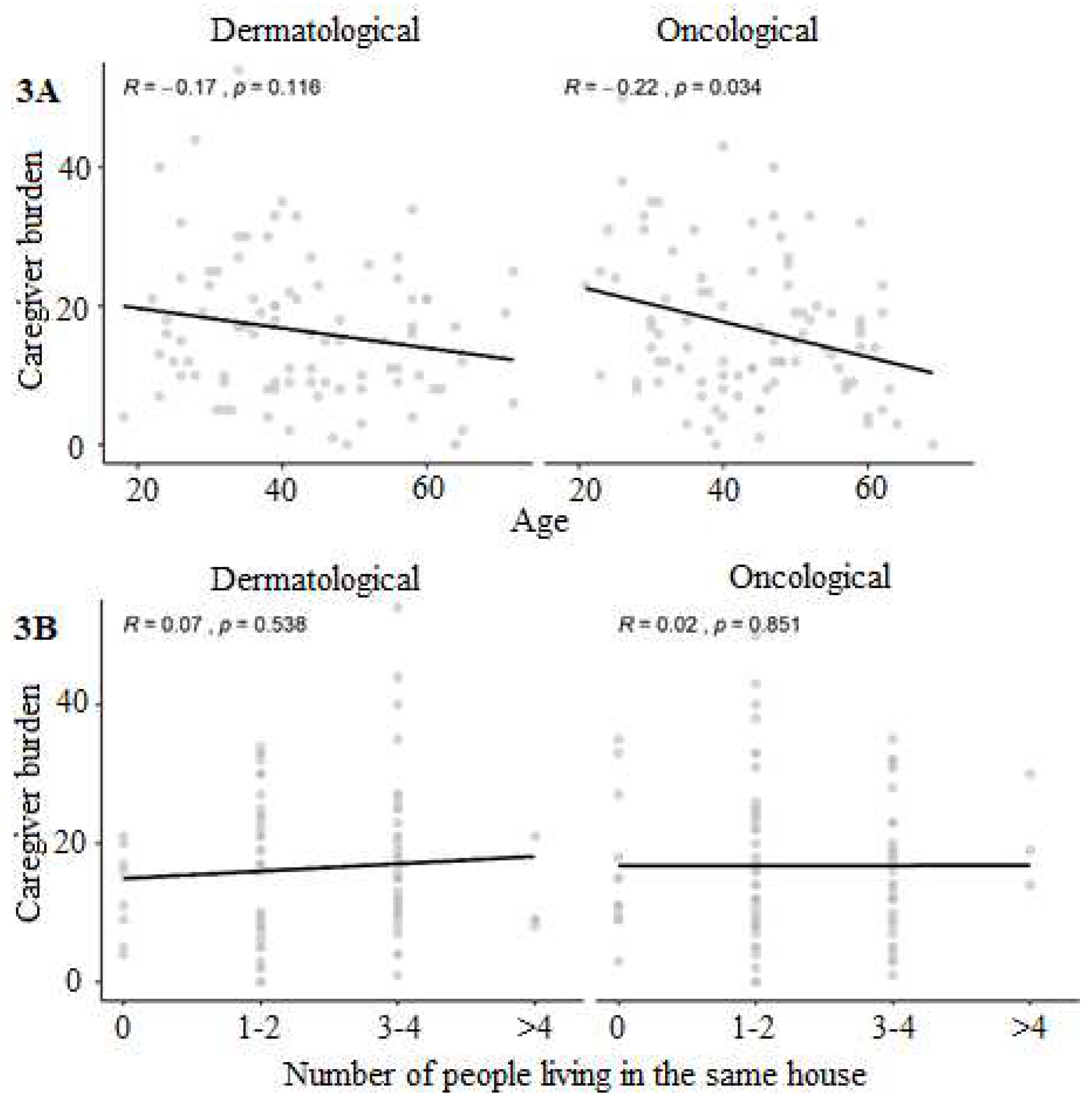

Concerning the interplay between caregiver burden and key factors—age, household composition, family income, diagnosis duration, and treatment duration according to the dermatological and oncological conditions, the results are shown in

Figure 3.

Scatter analysis of caregiver burden correlated with: age, number of people living in the same house, family income, diagnosis duration, and treatment, comparing caregivers of dermatological and oncological patients, with Spearman correlation value, along with its p-value. for family income, follow the correspondence: group 1 (up to 2 salaries), group 2 (2 to 4 salaries), group 3 (4 to 10 salaries), group 4 (10 to 20 salaries), group 5 (more than 20 salaries).

4. Discussion

Caring for a beloved pet with an illness or when approaching the end of their life can be challenging for many pet owners, especially considering the multifaceted nature of having a pet as a family member. While pets undoubtedly bring companionship and support, the increased needs resulting from illness or injury can amplify the inherent stresses associated with pet ownership [

19]. This highlights the importance of exploring the caregiver burden among pet owners. To our knowledge, the study represents the first exploration of caregiver burden in companion animal owners in Brazil. This unique contribution adds valuable insights to the global understanding of the complex dynamics involved in caring for ill pets. The findings from this study hold the potential to inform future research and contribute to the development of targeted support mechanisms for pet caregivers worldwide.

The present study demonstrated that over a third of the caregivers of animals undergoing treatment for oncological and dermatological pathologies experienced a significant level of burden at the time of evaluation, although no statistical differences were found in the degree of burden between these two veterinary specialties. In both cases, dealing with chronic conditions requires prolonged and often emotionally, physically, and financially demanding treatments, such as multimodal therapies for dermatological cases and chemotherapy for oncological patients. Caregivers may feel overwhelmed by recommended treatments, even when deeply attached to their pets, emphasizing the need for understanding and effective communication in the treatment process [

9].

Similar to the scenario of human patient caregivers, women are typically the primary caregivers for pets [

20]. A study conducted by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) in 2012 showed that 74.5% of caregivers with primary responsibility for these animals were female, a trend also observed in the current study [

21].

Spitznagel et al. [

12] found a higher degree of burden in caregivers of animals with dermatological pathologies compared to caregivers of healthy animals. Additionally, caregivers who perceived their animal’s disease as controlled or stable had a burden level (not elevated/normal) statistically similar to that of healthy patients. Disease stability was also a statistically significant factor related to burden in this study, emphasizing the importance of proper treatment in this population.

It was expected that sharing the responsibility for animal treatment with another individual would result in a lower degree of burden; however, there was no statistical difference between the degree of burden and whether the caregiver was solely responsible for the animal’s treatment in the current study. Similarly, there was also no difference in the number of people sharing the same household. A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be the uneven distribution of care responsibilities for these patients, resulting in a higher burden for the caregivers who responded to the questionnaire.

Despite no statistical difference being observed in the degree of burden with treatment duration (overall and in both specialties), there was a trend of increased burden with the animal’s therapy duration (positive correlation). Shaevitz et al. [

11] conducted a study assessing caregiver burden in caregivers of animals suspected of having cancer. It was observed that, in these cases, burden is present in the early stages of the disease. Furthermore, the results suggested that caregiver burden is similar in pet owners with cancer and pet owners with other diseases.

A statistical difference was observed in both the overall context and specifically among animals with dermatological diseases concerning the duration of diagnosis and the associated caregiver burden. This disparity was not evident in caregivers tending to animals with neoplasms. An explanation for this occurrence can be found by examining the difference in the diagnosis duration between these two specialties. The average diagnosis duration of animals with dermatological disorders (maximum of 144 months) was almost double that of animals with oncological pathologies (maximum of 48 months), which may be correlated with the difference in the diagnostic process between these two specialties. Association between treatment plan factors, such as changes in routine and the perceived challenge of following new rules for managing the animal’s condition, underscores the significance of treatment planning in influencing caregiver burden and highlights the importance of tailoring treatment strategies to align with the caregiver’s lifestyle and capabilities, thereby minimizing the potential negative impact on their caregiving experience [

9].

In most cases, animals with oncological diseases, once diagnosed, are referred to specialists to assess and/or initiate appropriate treatment. Regarding dermatological pathologies, many patients arrive at the specialist after numerous attempts at treatment with the general practitioner, and often the caregiver believes they already have an adequate diagnosis when, in many cases, what the animal presents is secondary to a main pathology yet to be diagnosed. As in the case of otitis secondary to allergies [

22], where the caregiver believes that otitis is the final diagnosis in itself. Thus, caregivers often spend years treating a recurring problem without proper resolution, implying a longer “diagnosis” time and burden.

In the current study, no statistical difference was found in any group between the degree of burden and the caregiver’s income. However, in all analyses, there was a negative correlation between the variables, meaning: the higher the income, the lower the burden. The surveyed sample reported a relatively high level of income and education (34.9% 4 to 10 minimum wages and 37.9% postgraduate), reflecting the typical clientele of the professional who is a specialist: individuals who choose to take their animal to a referring veterinarian and who can prioritize the health care of their companion animals. Britton et al. [

23] found that burden is significantly related to financial strain. This is because financial commitment is an important factor in this issue, as it can be both a risk for the development of the burden and a result of this burden [

2,

24].

Regarding the age of caregivers, a negative correlation was also found in all groups and was statistically significant in caregivers of animals with oncological pathologies and overall, which may reflect the trend of greater maturity and ability to deal with adversities acquired over time. In a study with owners of dogs with behavioral problems, caregiver burden was significantly less reported in older owners [

8]. In a study of caregiver burden in owners of dogs with cognitive dysfunction, the results demonstrated that those who lived alone and were between the ages of 25 and 44 years had an increased burden of care [

25]. Henning et al. [

16] found that the burden of care was lower in cat owners over 55 years of age. The study suggests that younger pet owners may experience a higher burden in caring for their animals compared to older caregivers due to specific life stage pressures for the younger, such as building a career, socializing, and childbearing, in contrast, older caregivers may find it easier to allocate time at home for pet care.

In the current study, a statistical difference was observed between the degree of burden in cat caregivers (higher burden) compared to dog caregivers. Spitznagel et al. [

15] researched the occurrence of caregiver burden specifically in cat caregivers. It was observed that owners of sick cats had a higher burden than owners of a healthy cat, but a slightly lower burden than owners of sick dogs. It was pointed out that the differences in the challenges of caring for these two species, such as giving baths, for example—dogs need more structure, can make it more difficult to care for the dog. Moreover, many cats do not receive routine veterinary care, even for chronic diseases, and this lack of veterinary oversight can lead to a lower demand for care for cat caregivers.

Examining caregiver burden in the context of veterinary patients is crucial for comprehending the roles and responsibilities of both clients and veterinarians, particularly in the treatment of seriously and terminally ill pets. The emotional labor in veterinary medicine, especially in client interactions surrounding serious or terminal illnesses, is substantial [

26]. The provided studies predominantly concentrated on the experiences of dog owners, highlighting the need for further research dedicated to understanding the nuanced aspects of caregiver burden in feline companionship, potentially uncovering unique challenges and dynamics associated with caring for cats with various health conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the impact that prolonged care for sick animals has on the psychosocial function of caregivers, regardless of the apparent severity of the disease. Understanding the client’s experience in caring for a sick pet provides a greater understanding of the client’s perspective, which can improve communication, potentially leading to better client adherence to the treatment plan and possibly job satisfaction for the veterinarian. Thus, more effective communication with the caregiver and treatments performed empathetically and less traumatizing are expected, adapted to generate less burden for these caregivers who experience very delicate situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.R.F.S. and A.P.C.N.; investigation, P.T.R.F.S. and A.P.C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.C and P.T.R.F.S.; review, F.M.C and A.P.C.V.; supervision and project administration, A.P.C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (Fapemig), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the NATIONAL HEALTH COUNCIL (protocol code CAAE 58860122.0.0000.5149).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Caregivers were fully informed about the purpose of the study, and they read/listened and signed an informed consent form, and authorization to allow us to use the data.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the caregivers for participating in the research. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zarit, S.; Reever, K.; Bahc-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver Burden: A Clinical Review. Jama 2014, 311, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremont, G. Family Caregiving in Dementia Geoffrey. Med. Health. R. I. 2011, 94, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Jacobson, D.M.; Cox, M.D.; Carlson, M.D. Caregiver Burden in Owners of a Sick Companion Animal: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belshaw, Z.; Dean, R.; Asher, L. “you Can Be Blind Because of Loving Them so Much”: The Impact on Owners in the United Kingdom of Living with a Dog with Osteoarthritis. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Patrick, K.; Gober, M.W.; Carlson, M.D.; Gardner, M.; Shaw, K.K.; Coe, J.B. Relationships among Owner Consideration of Euthanasia, Caregiver Burden, and Treatment Satisfaction in Canine Osteoarthritis. Vet. J. 2022, 286, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K.C. Living with and Loving a Pet with Behavioral Problems: Pet Owners’ Experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, K.; Ballantyne, K.C.; Cousins, E.; Spitznagel, M.B. Assessment of Caregiver Burden in Owners of Dogs with Behavioral Problems and Factors Related to Its Presence. J. Vet. Behav. 2023, 64–65, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Cox, M.D.; Jacobson, D.M.; Albers, A.L.; Carlson, M.D. Assessment of Caregiver Burden and Associations with Psychosocial Function, Veterinary Service Use, and Factors Related to Treatment Plan Adherence among Owners of Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 254, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Jacobson, D.M.; Cox, M.D.; Carlson, M.D. Predicting Caregiver Burden in General Veterinary Clients: Contribution of Companion Animal Clinical Signs and Problem Behaviors. Vet. J. 2018, 236, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaevitz, M.H.; Tullius, J.A.; Callahan, R.T.; Fulkerson, C.M.; Spitznagel, M.B. Early Caregiver Burden in Owners of Pets with Suspected Cancer: Owner Psychosocial Outcomes, Communication Behavior, and Treatment Factors. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 2636–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Solc, M.; Chapman, K.R.; Updegraff, J.; Albers, A.L.; Carlson, M.D. Caregiver Burden in the Veterinary Dermatology Client: Comparison to Healthy Controls and Relationship to Quality of Life. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 3-e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Hillier, A.; Gober, M.; Carlson, M.D. Treatment Complexity and Caregiver Burden Are Linked in Owners of Dogs with Allergic/Atopic Dermatitis. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32, 192-e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Patrick, K.; Hillier, A.; Gober, M.; Carlson, M.D. Caregiver Burden, Treatment Complexity, and the Veterinarian–Client Relationship in Owners of Dog with Skin Disease. Vet. Dermatol. 2022, 33, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Gober, M.W.; Patrick, K. Caregiver Burden in Cat Owners: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, J.; Nielson, T.; Nettifee, J.; Muñana, K.; Hazel, S. Understanding the Impacts of Feline Epilepsy on Cats and Their Owners. Vet. Rec. 2021, 189, no. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miot, H.A. Sample Size in Clinical and Experimental. J. Vasc. Bras. 2011, 10, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2022.

- Brown, C.R.; Edwards, S.; Kenney, E.; Pailler, S.; Albino, M.; Carabello, M.L.; Good, K.; Lopez, J. Family Quality of Life: Pet Owners and Veterinarians Working Together to Reach the Best Outcomes. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCVETY, D. Maintaining the Human-Animal Bond. In Treatment and Care of the Geriatric Veterinary Patient; MCVETY, D., GARDNER, M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, 2017; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- AVMA US Pet Ownership and Demographics Sourcebook 2012.

- Bajwa, J. Canine Otitis Externa—Treatment and Complications. Can. Vet. J. 2019, 60, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, K.; Galioto, R.; Tremont, G.; Chapman, K.; Hogue, O.; Carlson, M.D.; Spitznagel, M.B. Caregiving for a Companion Animal Compared to a Family Member: Burden and Positive Experiences in Caregivers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.R.; Kwak, J.; Acquaviva, K.D.; Brandt, K.; Egan, K.A. Transformative Aspects of Caregiving at Life’s End. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2005, 29, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.L.; Smith, B.P.; Hazel, S.J. Guardians’ Perceptions of Caring for a Dog with Canine Cognitive Dysfunction. Vet. Rec. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, K.J. Exploring Caregiver Burden within a Veterinary Setting. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).