1. Introduction

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a section of the intestine into the lumen of its adjacent segment that may cause mechanical obstruction. In contrast to the pediatric population, in adult patients it is an uncommon cause of bowel obstruction and is found in approximately 5% of the patients [

1].

Preoperative diagnosis in adult patients requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and is in about half of the cases impossible. The scenario of a not resolving ileus in a young adult patient, with no previous surgical procedures in the abdomen, should alert the surgeon to exclude infrequent causes for the obstruction such as intussesception. Computed Tomography (CT) is according to the literature the most helpful imaging modality but its accuracy is still moderate and lies between 58 and 100% [

2].

While the cause of intussusception in adult patients is most of the times an underlying neoplasm, the location of the intussusception, the symptoms and the type of neoplasm (benign or malign) vary greatly from patient to patient, thus rendering the surgical treatment of the disease to a challenge for every surgeon. In this study we present four cases of adult intussusception with unique background, symptoms and etiology and discuss the key-points for diagnosis and appropriate surgical treatment by reviewing the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

Four adult patients with bowel intussusception that underwent surgery in our department from 2012 to 2019 were enrolled in the study.

The

first case concerned a 48-year-old female patient, who presented to the emergency department with diffuse abdominal pain over the last 24 hours and vomiting. Her medical and surgical history were free. The laboratory results showed an elevated White Blood Cell (WBC) count (17.4 mm

3/μL, normal range 4.3-10.3 mm

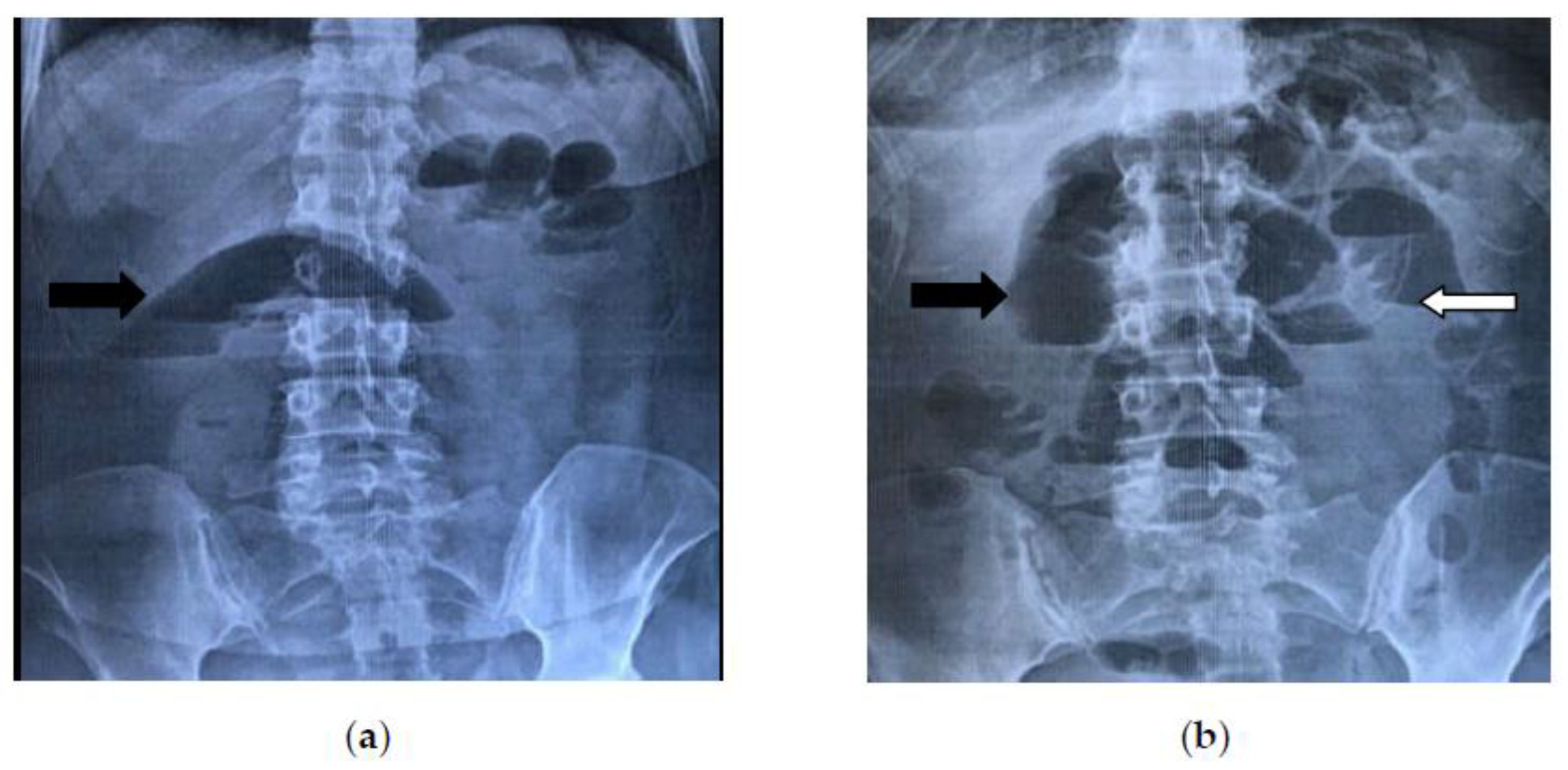

3/μL) and a normal C-Reactive Protein (CRP) value (0,4 mg/dL, normal range < 0,5 mg/dL). Plain abdominal imaging in an upright position revealed air fluid-levels typical for an intestinal obstruction

(Figure 1a), whereas the ultrasound examination was non-conclusive. The computed tomography (CT) scan showed a distention of the small intestine until the terminal ileum, without identifying the cause of obstruction. Initially, a nasogastric tube was placed for conservative management. After 48 hours the patient’s condition as well as the plain abdominal imaging

(Figure 1b) showed no signs of improvement, so an exploratory laparotomy was decided.

This revealed an entero-enteric intussusception of the terminal ileum approximately 30 cm proximal of the ileocaecal valve. An en-block resection of the affected segment (about 10 cm in length) and an end -to -end, hand - sewed anastomosis were conducted. A small, intraluminal, palpable tumor was found to be the cause of intussusception after a close inspection of the specimen. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 8th postoperative day. The histopathological and immunohistochemichal report revealed a benign, 2,5 cm submucosal neoplasm of mesenchymal origin with characteristics of a neurofibroma (CD117, CD34, S100 and Smooth Muscle Actin-SMA- negative).

The

second case concerned a 38-year-old female patient with a free medical history, who presented in the emergency department with progressive recurrent epigastric pain, vomiting and diarrhea over the last ten days. Physical examination revealed tenderness and a palpable mass in the upper abdomen. All laboratory inflammation markers were within the normal range (WBC: 8.8 mm

3/μL, CRP: 0,0 mg/dL). At first, an ultrasound examination was performed and the diagnosis of a bowel intussusception was suspected through demonstration of a typical "target sign"

(Figure 2).

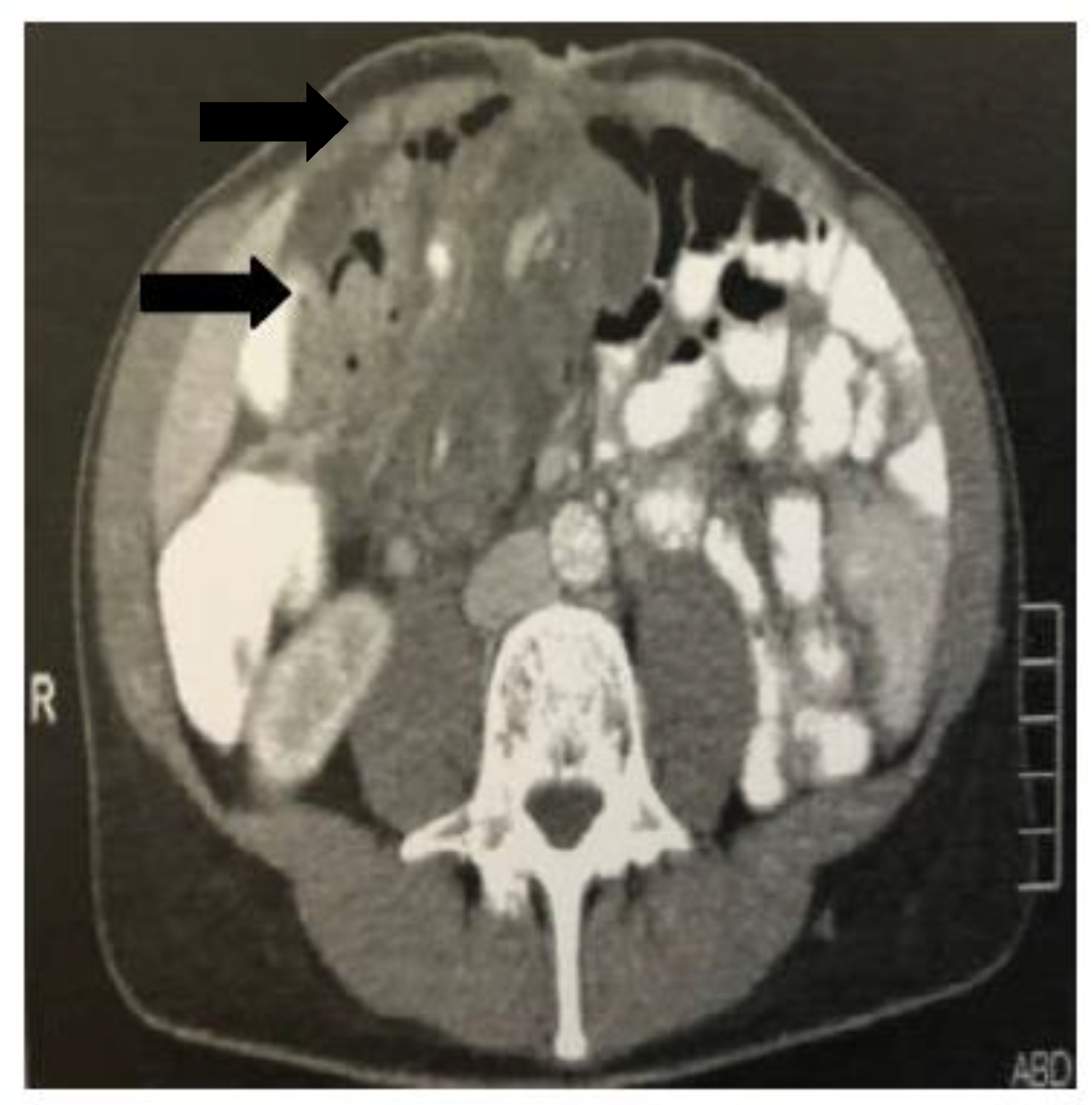

This was later confirmed through a CT scan which revealed an abdominal "mass" with intestinal loops forming a multilayer concentric ring, expanding from the ileocolic valve till the left upper abdomen, suggesting an ileocolic intussusception

(Figure 3).

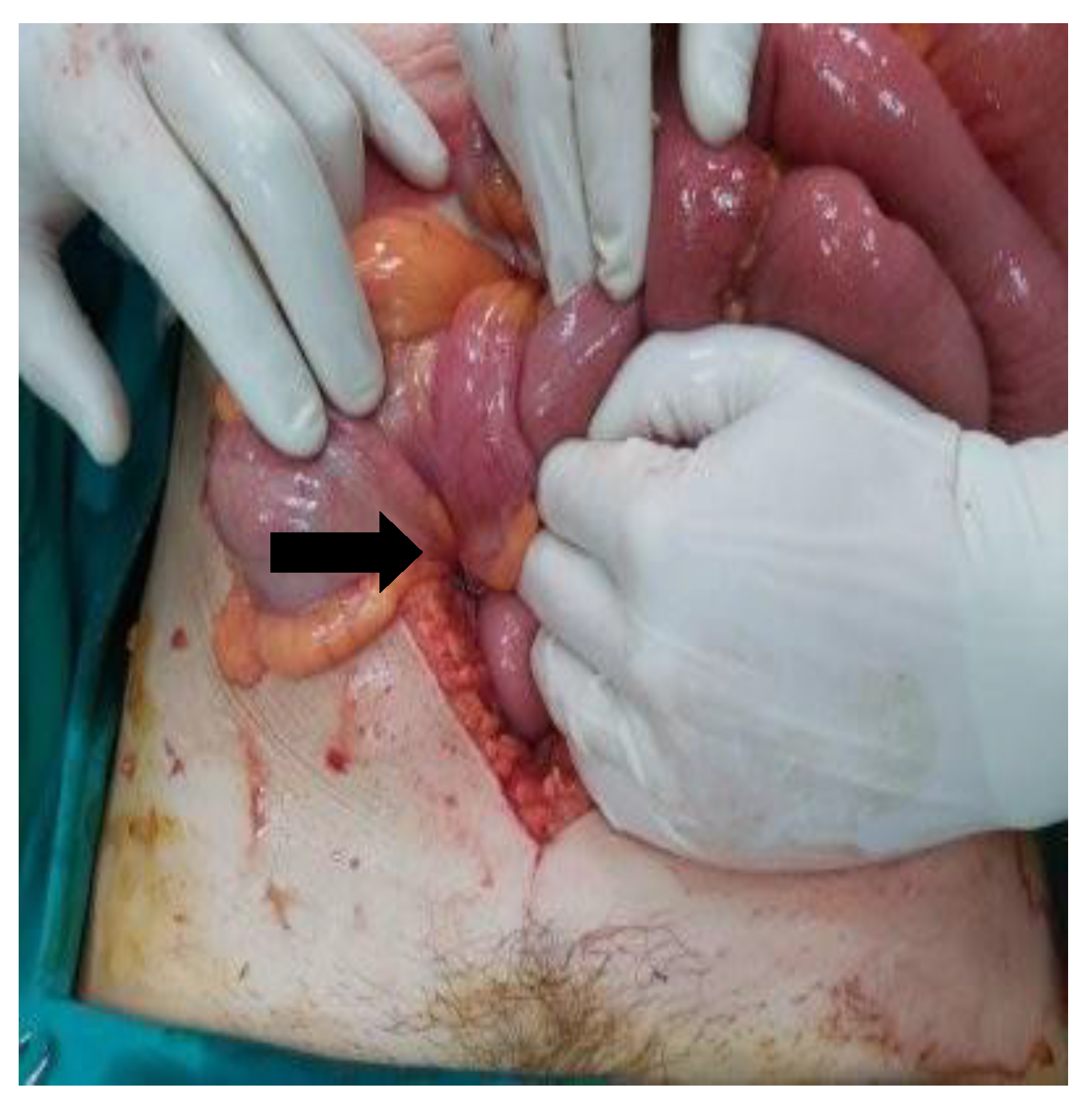

An emergency surgery was conducted, which further confirmed the CT findings by revealing an ileocolic intussusception of a long small bowel segment (approximately 40 cm) that was reaching till the left colic flexure [

Figure 4].

The decision was taken to carefully realign the small intestine in order to limit the extent of resection. After reduction a palpable tumor was found in the caecum as the cause of intussusception. A small enterotomy in the colon ascendens enabled direct view of the tumor, which seemed macroscopically suspicious for malignacy, therefore it was decided to perform a right colectomy with Complete Mesocolic Excision (CME) and a hand-sewn side-to side ileotransverse anastomosis. The histological examination revealed a villous adenoma,with a maximum diameter of 3,5 cm, located on the base of the appendix vermiformis, with mostly low grade epithelial dysplasia but also few sites of high grade dysplasia. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 6th postoperative day.

The

third case (already published from our center as a single case report in 2012) [

3] was a 34-year-old female patient with a free medical history who presented with an intermittent diffuse abdominal pain over the last two months. On clinical examination only a mild tenderness and distension over the right iliacal fossa was notable and routine blood tests were unremarkable. At first a double-contrast barium enema was performed, which revealed a filling defect in the caecum (for figures please refer to the original article, reference number 3). A subsequent colonoscopy was non-diagnostic because it failed to demonstrate the part of the colon beyond the hepatic flexure. Therefore a CT scan was performed which revealed a large endoluminal mass extending from the caecum to the colon ascendens with fat density. A scheduled laparotomy was conducted, during which a colocolic intussusception of the caecum was found. A right hemicolectomy with side-to-side ileotransverse anastomosis was performed. The histopathological report revealed a 6 x 5 x 4,5 cm pedunculated, submucosal lipoma of the caecum with ulcerated overlying mucosa. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 8th postoperative day.

The fourth case concerned a 56-year-old female patient who presented in our emergency department due to an acute epigastric pain over the last 24 hours and severe vomiting. Furthermore the patient reported a weight loss of 15 kilograms during the last year and an episode of intestinal obstruction a year ago, that was treated conservatively. The rest of her medical history included familiar adenomatosis polyposis (FAP), hyperthyroidism, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, megaloblastic anemia and hyperuricemia and her surgical history consisted of a subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (FAP) and an endovascular treatment of an abdominal aorta aneurysm. Clinical examination on admission revealed a diffuse tenderness and a slight distension of the abdomen as well as a palpable mass in the left lower quadrant. Laboratory inflammatory markers were elevated (WBC 12.9 mm3/μL, CRP 7,1 mg/dL). Plain abdominal radiograph showed a single, large, air fluid level and CT revealed a possible intussusception of the initial part of the jejunum forming an abdominal mass with a maximum diameter of 7 cms and causing a complete obstruction of the lumen. The patient underwent emergency laparotomy which confirmed the CT diagnosis of jejunojejunal intussusception. The affected segment was approximately 20 cm long and was ischemic. An extended jejunum resection (approximately 65 cm) and a side-to-side anastomosis near the Treitz ligament, with a use of a linear cutter were performed. Following examination of the specimen the cause of the intussusception was found to be an intraluminal, polypoid mass. The histopathological examination revealed a well differentiated adenocarcinoma of the small intestine with a maximum diameter of 5,5 cms without lymph node metastasis. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 10th postoperative day.

3. Results

All four patients that were included in the study were female and their mean age was 44 years old (range from 34-56).

Two of the patients presented in the emergency department with an acute abdomen and one with a subacute abdomen. Only one of the patients underwent a scheduled laparotomy. In all four cases acute or intermittent abdominal obstruction was the leading pathology with vomiting, diffuse or local abdominal pain and distension being the most common clinical symptoms. In two of the patients there was also a palpable mass present during clinical examination.

Preoperative diagnosis was made in two out of the four patients (50%). CT scan was performed in all patients and was diagnostic in 2 of the 4 cases (50%). Abdominal ultrasound was performed in two patients. In the first one it was non-conclusive, whereas in the second patient an intussusception was suspected that was later confirmed with a CT scan. Barium enema was non-diagnostic in one patient and plain abdominal radiograph revealed a mechanical ileus without identifying the cause in two patients.

The site of the intussusception varied greatly between the four patients (one ileoileal, one ileocolic, one colocolic and one jejunojejunal intussusception) but the cause of the disease was in all 4 cases the presence of a neoplasm. The tumor was malignant in one case (adenocarcinoma of the jejunum- medical history of FAP) and benign in the rest of the cases (one villous adenoma, one neurofibroma and one lipoma). In all four cases an oncological resection of the affected segment was performed (right hemicolectomy in two cases, segmental jejunum and segmental ileal resection). Reduction of the intussusception prior to resection was performed only in one case to prevent unnecessary extended resection. Intestinal ischemia was present in the case of jejunojejunal intussusception. The postoperative course of all patients was uneventful and the mean hospital stay was 8 days (range from 6-10).

(Table 1)

4. Discussion

Intussusception was first described as a clinical entity in 1674 [

4] and is defined as the invagination of a proximal segment of the intestine into the immediately adjacent distal part that is caused by an abnormality in the peristaltic movement of the evolved segment. The cause of this abnormality may be idiopathic or traction produced from the existence of an intra- or extraluminal lead point such as a neoplasm. This may cause intermittent or acute mechanical obstruction and in worst case scenario even impairment of mesenteric vascular flow and ischemia of the affected segment [

5].

Intestinal intussusception is most commonly found in the pediatric population (peak age 6 to 18 months) but rarely (in about 1-5% of the cases) may be the cause of bowel obstruction also in adults patients [

6]. According to the literature, the mean age of adult patients with intussusception is 50 years and there is no gender predominance [

5]. Though, all four cases that we present were female, with a mean age of 44. Similar to our results, Wang et al. [

7] found in a large retrospective series of 41 cases a male to female ratio 1/1.3 and a female mean age of 47.

Regarding location of intussusception in adult patients, the small bowel is generally affected more frequently than the colon and the most common types of intussusception are the ileocolic, the enteroenteric and the colocolic one [

8]. On the other hand, the upper gastrointestinal tract is rarely involved with few cases of gastroduodenal intussusception being described in the literature [

9]. Finally, even more rare is the colorectal [

10] and the coloanal intussusception [

11]. In our series we present two cases of enteroenteric, one of ileocolic and one of colocolic intussusception.

In contrast to children where the etiology of intestinal intussusception is most of the times idiopathic, in adult patients an underlying cause is responsible for about 90% of the cases [

1,

6,

12,

13]. In the small bowel benign (hamartoma, hemangioma, inflammatory polyp, neurofibroma) or malignant (GIST, lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma, neuroendocrine tumor, metastatic melanoma) neoplasms account for 2/3 of the non-idiopathic cases, whereas Meckel's diverticulum, adhesions or submucosal hemorrhage are other less common causes. On the other hand, in the colon, neoplasms that may cause intussusception are adenomas, lipomas and adenocarcinomas [

5]. In all of our cases the underlying cause was the existence of a neoplasm.

Regarding clinical presentation of the disease, the classic triad of symptoms that is commonly found in children (acute abdominal pain with sudden onset, palpable mass and bloody stool) [

14], is rarely found in adult patients [

15]. Symptoms in adult intussusception vary greatly and may be acute, chronic or intermittent. Abdominal pain with signs of complete or partial bowel obstruction such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention and constipation are the predominant symptoms, with a duration that varies from days to weeks or even months [

6,

12]. Rectal bleeding, diarrhea or presence of an abdominal mass may also be indicative of intussusception [

5,

7]. A palpable mass is mostly found in colonic lesions in about 10-30% of the patients [

5,

7], but in our series it was detected in two patients with small bowel intussusception. Characteristic for these cases was the fact that the proximal part of the intestine (intusssusceptum) had a very long length (40 cm in the second case and 65 in the fourth). The main symptom of all our patients was abdominal pain of variable duration (24 hours to 2 months).

Differential diagnosis of adult intussusception includes all disorders that are related to the pathology of an obstructive ileus or an acute abdomen. Because of the absence of pathognomonic symptoms and the rarity of the disease, diagnosis may be challenging, resulting sometimes to delay of the surgical procedure and complications such as bowel ischemia, generalized peritonitis and shock. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic imaging modalities is moderate in adult intussusception, and the choice of imaging varies between patients and depends from the suspected diagnosis.

Plain abdominal radiograph in an upright position may reveal signs of intestinal obstruction (distended bowel loops, absence of air in the large bowel) or perforation (free air under the diaphragm). It is a cost effective and sensitive modality in terms of diagnosing bowel obstruction, but it lacks on specificity in determining the exact location and the cause of it (i.e., intussusception) [

16]. On the other hand, contrast studies such as barium enema may be helpful in diagnosing patients with colonic intussusception (as in the third case of the present study), but their use is limited in adult patients, especially in an emergency setting [

15].

Ultrasound is a noninvasive, non-radiation method, therefore is considered the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing intussusception in children but may be pathognomonic also in adult patients. The typical "target or bull's eye sign” that is created from the intussuscepted loops that are forming an external ring around the intussusceptum may be depicted by an experienced radiologist [

17] (

Figure 2). In pediatric patients the reported sensitivity of the method is almost 100%, but in adults patients it is much lower (30-60%) [

6,

7,

18]. However, according to Wang et al. if a palpable mass is present, the diagnostic accuracy of the method is much higher and may reach 91% [

7]. From the four cases that we present ultrasound was performed in two patients with epigastric pain to exclude a gallbladder pathology and was diagnostic only in the second case that presented also with a palpable mass. Regarding CT scan, it seems to be the most useful diagnostic tool in adult intussusception, with a reported diagnostic accuracy ranging from 78% up to 100% [

6,

7,

12,

18,

19]. The intussusception is depicted as an inhomogeneous mass lesion with a central area of fat with enhanced vascularization (intussuscepted mesentery) and multiple, eccentric layers that represent the thickened segments of bowel (intussusceptum and intussuscipiens) [

20]. Furthermore, CT may provide indirect information in cases of a malign disease (metastatic lesions in the liver, lymphadenopathy) but most of the times is not capable to depict the primary neoplasm that causes the intussusception.

Finally, in addition to CT scan, in cases of suspected colo-colic or ileocolic intussusception, preoperative colonoscopy is a useful tool to distinguish between benign and malign lesions and sometimes may be even therapeutic by realigning the intussusception. It should be noted though, that availability in an emergency setting varies greatly from hospital to hospital [

13].

Concerning treatment of the disease, in contrast to pediatric intussusception that is most of the times ileocolic and idiopathic, conservative approaches (pneumatic or contrast enemas) are not recommended in adult intussusception. Surgical intervention is the gold standard in order to definitely treat the underlying cause. Though, some aspects of the treatment regarding operative technique and extend of resection remain still controversial. For example, several authors advocate reduction of the intussusception before resection of the pathological segment [

18,

21], while others recommend primary resection en block, without reduction, in order to reduce unnecessary manipulation on the specimen and minimize the risk of bacterial and tumor spillage in cases of malignancy [

8,

15]. Because most of the times preoperative evaluation of the underlying cause is missing, the decision should be tailored and customized upon intraoperative findings (age of patient, condition of the bowel, location of intussusception, length of intussusceptum and malignancy suspicion). In cases in which the bowel is inflamed or ischemic, it is advisable not to attempt reduction but to proceed directly with resection. Moreover, due to the high risk of malignancy colonic lesions should not be reduced and oncologic hemicolectomy with adequate lymphadenectomy should be performed. A limited resection after reduction of intussusception is justified only in cases where a benign diagnosis has been made pre- or intraoperatively or in patients in which resection may result in short gut syndrome. Furthermore, in the scenario of a very long intussusceptum without signs of ischemia (second case), careful reduction before resection should be considered in order to avoid unnecessary resection of the whole bowel segment. Finally, intraoperative colonoscopy and diagnostic enterotomy may serve as adjunctive tools to better evaluate the underlying cause of the intussusception and minimize extend of resection [

13].

5. Conclusions

Adult intussusception is a rare pathological entity that presents with non-specific symptoms that are related to subacute or acute bowel obstruction and requires surgical intervention. Preoperative diagnosis of the disease is challenging, therefore the surgeon should be aware of its existence. Most of the times the underlying cause of intussusception is a undiagnosed benign or malign neoplasm that requires resection. Due to the significant likelihood of malignancy, especially in colon intussusception, oncologic resections without realignment of the affected segment should be performed, because intraoperative evaluation of the nature of the neoplasm is most of the times impossible. However, exceptions to this rule do exist, therefore we suggest to individualize operative strategy case by case.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Stefanos Atmatzidis and Dimitrios Raptis; methodology, Stefanos Atmatzidis; software, Nikolaos Voloudakis; validation, Stefanos Atmatzidis, Ioannis Koutelidakis and Grigoris Chatzimavroudis; formal analysis, Vasiliki Elisavet Stratinaki; investigation, Nikolaos Voloudakis; resources, Stefanos Atmatzidis, Dimitrios Raptis and Basilios Papaziogas; data curation, Eirini Martzivanou; writing—original draft preparation, Eftychia Kyriakidou; writing—review and editing, Stefanos Atmatzidis; visualization, Athanasios Papatzelos; supervision, Stefanos Atmatzidis; project administration, Stefanos Atmatzidis; funding acquisition, Basilios Papaziogas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zubaidi, A.; Al-Saif, F.; Silverman, R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum 2006, 49, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinis, A.; Yiallourou, A.; Samanides, L.; Dafnios, N.; Anastasopoulos, G.; Ioannis Vassiliou, I.; Theodosopoulos, T. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: A review. World J Gastroenterol 2009, 15, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmatzidis, S.; Chatzimavroudis, G.; Patsas, A.; Papaziogas, B.; Kapoulas, S.; Kalaitzis, S.; Ananiadis, A.; Makris, J.; Atmatzidis, K. Pedunculated cecal lipoma causing colo-colonic intussusception: a rare case report. Case Rep Surg. 2012, 2012, 279213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moulin, D. Paul Barbette, M.D.: a seventeenth-century Amsterdam author of best-selling textbooks. Bull Hist Med 1985, 59, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cera, SM. Intestinal intussusception. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008, 21, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azar, T.; Berger, D.L. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg 1997, 226, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Cui, X.Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, J.; Xu, Y.H.; Guo, R.X.; Guo, KJ. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review of 41 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 3303–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weilbaecher, D.; Bolin, J.A.; Hearn, D.; Ogden, W. Intussusception in adults. Review of 160 cases. Am J Surg. 1971, 121, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Kong, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, W. Gastroduodenal intussusception caused by gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor in adults: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2022, 50, 3000605221100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.A.; Mohamud, A.A.; Acet, E.; Guler, I.; Adani, A.A. Colorectal intussusception with rectal prolapse related to cecal lipoma in adult: A rare case report and review of the literature. Ann Med Surg 2022, 82, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarthi, S.; Smith, R.C. Adult intussusception: case reports and review of literature. Postgrad Med, J. 2005, 81, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barussaud, M.; Regenet, N.; Briennon, X.; de Kerviler, B.; Pessaux, P.; Kohneh-Sharhi, N.; Lehur, P.A.; Hamy, A.; Leborgne, J.; le Neel, J.C.; Mirallie, E. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusception. Int J Colorectal Dis 2006, 21, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-T.; Wu, C.C.; Yu, J.C.; Hsiao, C.W.; Hsu, C.C.; Jao, S.W. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years’ experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2007, 50, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, M.D.; Pablot, S.M.; Brereton, R.J. Paediatric intussusception. Br J Surg. 1992, 79, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, L.K.; Cunningham, J.D.; Aufses, A.H. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. J Am Coll Surg 1999, 188, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakan, S.; Caliskan, C.; Makay, O.; Denecli, A.G.; Korkut, M.A. Intussusception in adults: Clinical characteristics, diagnosis and operative strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 1985–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.J.; Arkell, L.J.; Williams, J.T. Ultrasound diagnosis of adult intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol 1993, 88, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Honjo, H.; Mike, M.; Kusanagi, H.; Kano, N. Adult intussusception: A retrospective review. World J Surg. 2015, 39, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkan, N.; Haciyanh, M.; Yildirim, M.; Sayhan, H.; Vardar, E.; Polat, A.F. Intussusception in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis 2005, 20, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.Y.; Warshauer, D.M. Adult intussusception: Diagnosis and clinical relevance. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003, 41, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarr, M.G.; Nagorney, D.M.; Mc Ilrath, D.C. Postoperative intussusception in the adult: a previously unrecognized entity? Arch Surg. 1981, 116, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).