Introduction

At the end of the 19th century, significant transformations swept through the American educational landscape after the Civil War(Emoto, H. 2017). A wave of large-scale construction initiatives reshaped campuses, ushering in new architectural paradigms. The Collegiate Gothic style, which blended elements from the English Tudor Gothics with aspects of French Beaux-Arts traditions, emerged as a flexible and unstructured architectural language(Coulson et al.2015). It quickly became ideal for diverse building types and comprehensive campus planning.

Scholars trace the origins of the Collegiate Gothic style to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England, emphasizing its architectural representation of a venerable academic lineage(Chapman, M. P. 2006; Ziolkowski, J. M. 2018). Gradually, this style became symbolic of the architectural tradition on American campuses, reflecting the values and practices of higher education in the United States(Morgan, W. 1989).

Simultaneously, China was undergoing significant transformations in a different part of the world between 1900 and 1927. A crucial element of this change was the 1905 abolition of the imperial examination system(Lutz, J. G. 1958). Concurrently, Christian missionaries played a substantial role in introducing advanced medical and educational approaches to China. Notably, missionaries from the Methodist Episcopal Church South 1 (M.E.C.S) were not merely purveyors of religious doctrine(Williams Jr, M. O. 1993); they laid the groundwork for the subsequent introduction of the Collegiate Gothic architectural style in the region.

In this dynamic context, Soochow University, founded in 1900, became a pivotal institution. The university's visionary founders conceived it not merely as a place of learning within walls but as a model and exemplar for higher education in China. Reverend Y.J. Allen, the founder of Soochow University, shared this vision during a General M.E.C.S meeting in New Orleans in 1901:

"At Soochow University, we hope to have more than a mere school for the education of the pupils who come within its walls. We hope to have a model, an example of schools, [...]. That is a model of its kind, and I believe it is to be the progenitor of schools and the mother of pupils". (General M.E.C.S. 1901.p.366).

Soochow University was among the forefront of thirteen Christian universities in China, collectively shaping modern Chinese education and culture. While research on Collegiate Gothic architecture within the context of these institutions has received significant attention(Cai, L., & Deng, Y.2011,2012; Kong, N., & Liu, S. 2020), the focus on Soochow University has primarily centered on its founding histories and architectural lineages(Hu, X. 1985), with less emphasis on comprehending the unique architectural styles embraced by Soochow University. Consequently, this study aims to address this gap by exploring the distinctive status of Soochow University's Anderson Hall within the landscape of modern Chinese Christian universities.

This study centers on Soochow University's Anderson Hall, a pivotal subject for investigating the Collegiate Gothic architectural style. Our research methodology combines historical analysis and empirical research. We draw upon valuable primary sources, including records from the Asia Christian Higher Education Committee at Yale Divinity School (U.S.A.) and historical documents related to architecture and renovations from the Suzhou University Archives and Suzhou Municipal Archives. We further enrich this analysis through additional fieldwork and an extended literature review to provide a comprehensive historical context and contextualize Anderson Hall within the broader milieu of Christian universities.

Our empirical foundation rests on thorough on-site surveys conducted between 2019 and 2023, complemented by architectural drawings and photographic documentation from the same period. Systematically examining available source materials, we aim to thoroughly explore the origins, influences, and distinctive architectural features of the Collegiate Gothic style within Anderson Hall. Additionally, we conducted a detailed analysis of how architects integrated this style into the building's layout, structural elements, and façade.

Impact of missionary-driven Style

In the 1850s and 1860s, influential American missionaries, including J. W. Lambuth and W. Allen, arrived in Shanghai, actively promoting educational initiatives. Its influence gradually extended beyond Shanghai, impacting neighboring areas (Wang, G. 2010). However, before 1900, traditional Confucian education was the prevailing educational system. During this era, tensions arose between the conventional scholar-gentry representing Chinese society and Western missionaries, rendering missionary work relatively challenging. To alleviate local grievances and operate within financial constraints, the M.E.C.S adopted a strategy that assimilated local customs, including architectural styles. In modern times, the M.E.C.S founded schools in China, including the early Buffington Institute (1871-1899)and a few others, incorporating Chinese architectural styles.

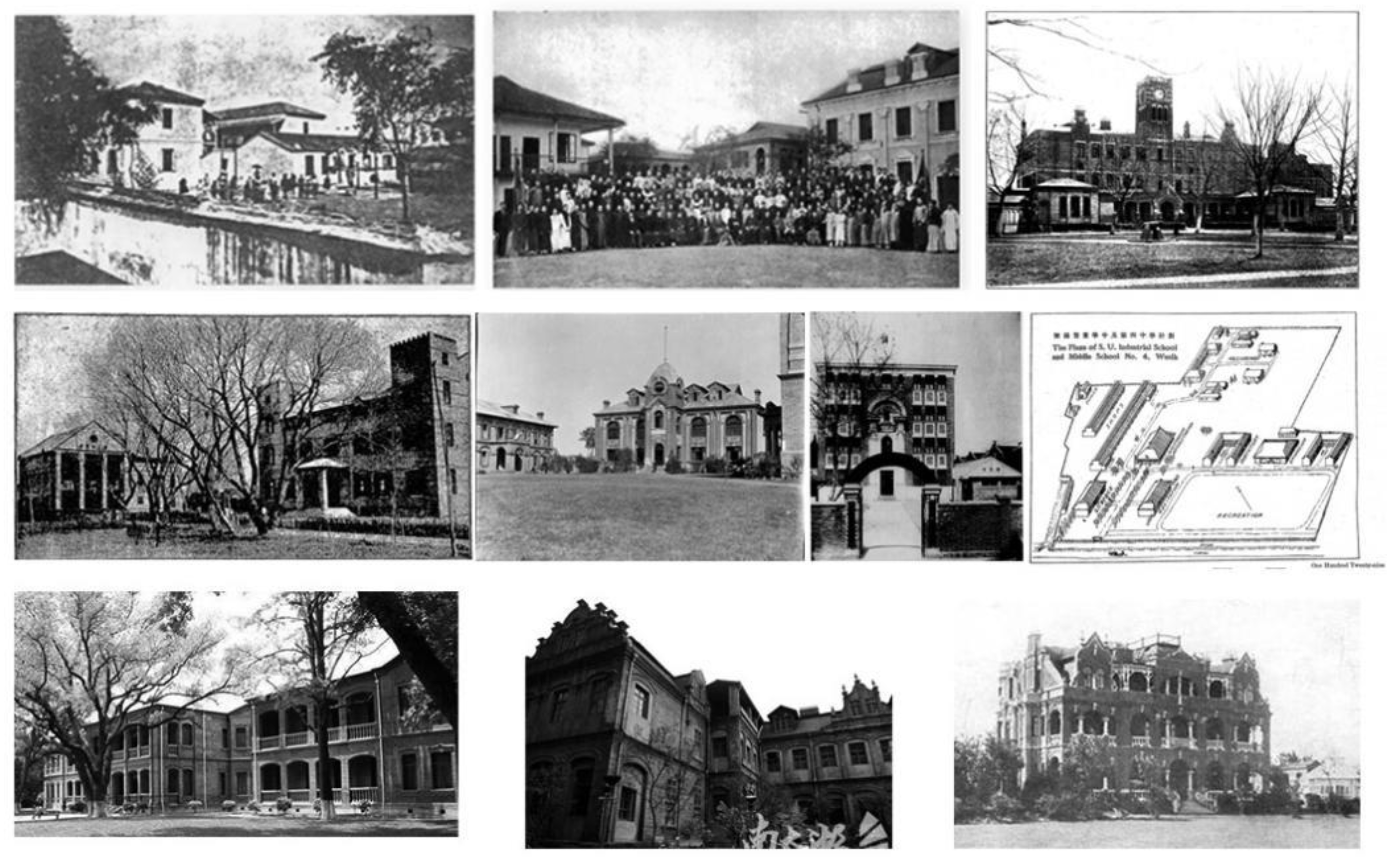

However, it's worth noting that the remaining 11 schools, including Soochow University, exclusively adopted Western architectural styles for their campus buildings, highlighting a distinctive architectural preference(Li, X. 2022)(

Figure 1). The early 20th-century trend of the Qing government emulating "foreign regulations" may have influenced the Board of Trustees in their choice of campus design. However, this decision was rooted in the Board's belief in educational equality and their aspiration to establish a university on par with American institutions. Religion played an integral role in shaping campus functions and, by extension, architectural and spatial features.

The influence of Western architectural styles extended beyond China during missionary activities. In the context of early Japanese modernization, introducing Christian missionary work in Japan created a synergistic relationship with the growth of Western-style education. Notably, the first pioneers of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, who ventured into Japan, originated in the M.E.C.S missions in Shanghai and Suzhou. Figures like W. R. Lambuth2 contributed to establishing Kwansei Gakuin University in Japan, representing a significant milestone in the M.E.C.S's educational achievements (Hong, M. 2020).

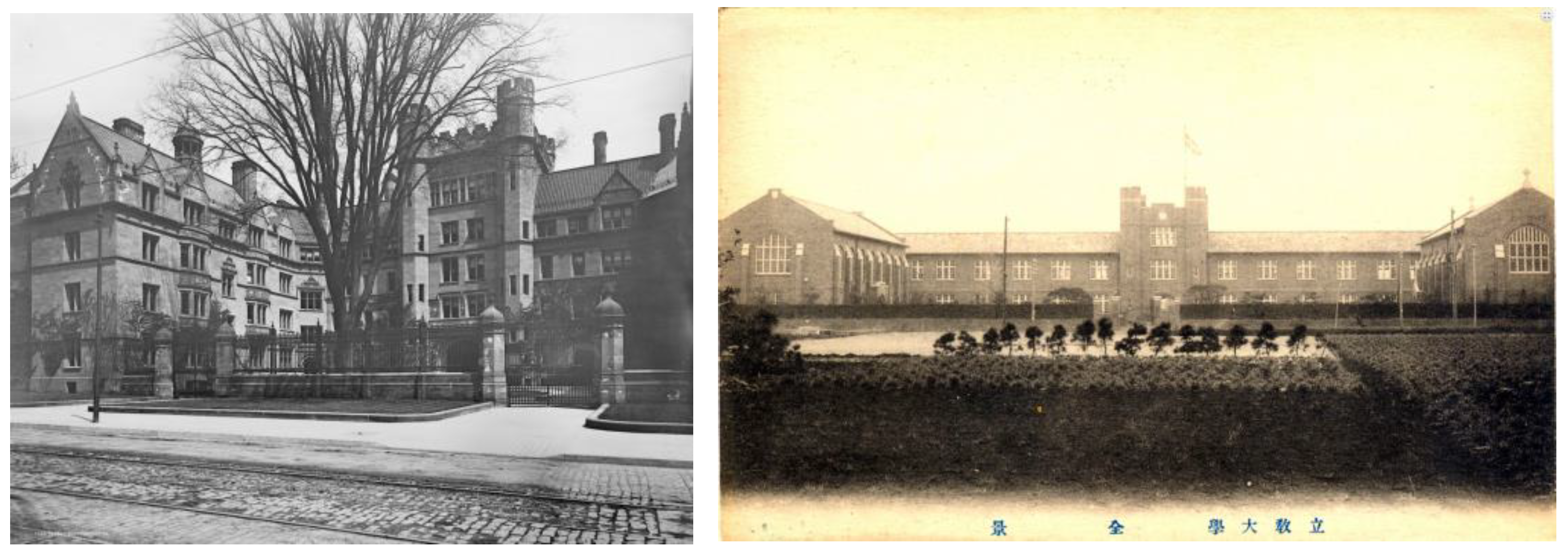

During the early 20th century, Japanese architectural circles displayed a distinct inclination toward preserving European classical designs (Nate. 2020, February 15). Before the 1920s, the Collegiate Gothic architectural style had limited adoption in Japanese Christian university buildings. Only the Anglican Church's Rikkyo University in Tokyo pioneered the Collegiate Gothic style (Rikkyo Gakuin Archives Center 2007). Murphy & Associates, entrusted with the architectural design of Rikkyo University's main Hall, heavily influenced it based on the architect's alma mater, Yale University Vanderbilt Hall (

Figure 2). This choice demonstrated the direct emulation of Collegiate Gothic styles by architects.

Similarly, the expansion of the Korean M.E.C.S was closely related to the M.E.C.S in China. This connection traces back to 1884 when Yoon Chi-ho sought refuge in Shanghai after the Kabo Reforms in Korea. Yoon Chi-ho received a Christian education at the Anglo-Chinese College (1881-1911). Upon returning to Korea, he invited the M.E.C.S to engage in missionary work (Ma, G. 2012).In response to Yoon Chi-ho's invitation, the M.E.C.S commenced official missionary activities in 1896. Yoon Chi-ho's diary entries provide evidence of the decision-making process regarding the Chosen Christian College's3 architectural style.

"The Board of Directors for the Chosen Christian College met at Dr. Avison's to discuss the constitution yesterday morning, also had a lengthy discussion about the kind of architecture the College is to have―all Korean or Foreign―decided to have the College portion purely foreign." (List of materials | Korean History Database. 2018).

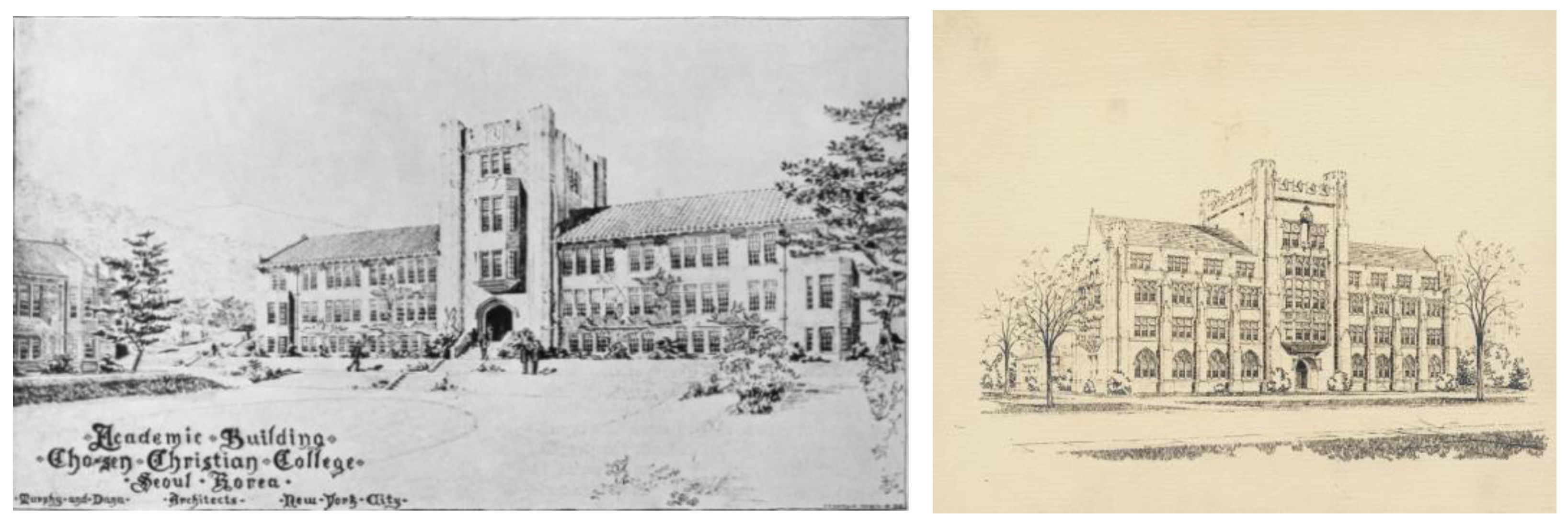

The earliest Collegiate Gothic examples can be traced to the Chosen Christian College's Underwood Hall in 1924(Jung, S. Y. 2006)(Kim, B. W., & Kim, Y. J. 2019). Notably, the architect responsible for the design, H. K. Murphy, has significant relevance. His architectural blueprints for the Chosen Christian College exhibited a high degree of resemblance to those of the University of Chicago (

Figure 3).

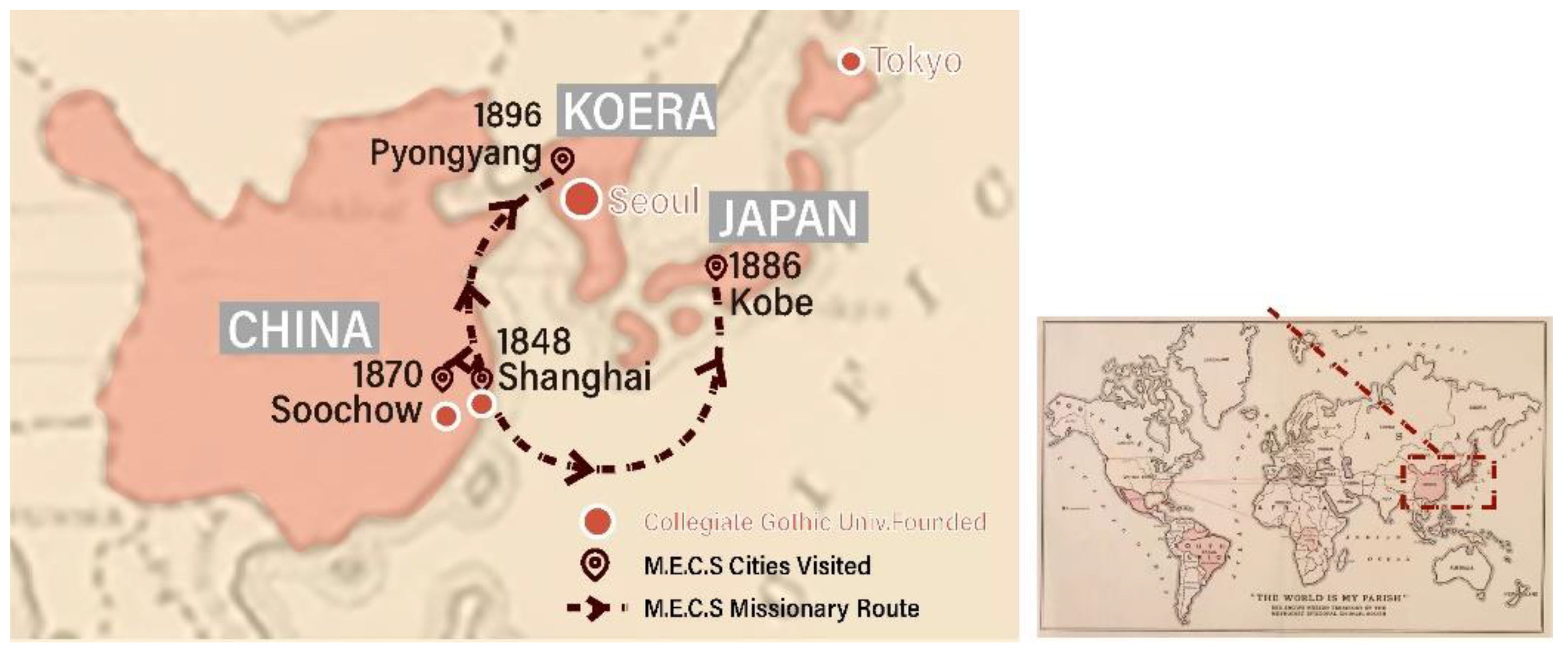

The influence of Western architectural styles extended beyond China and significantly impacted the development of higher education in Japan and Korea during missionary activities (

Figure 4). The historical context provided in this chapter is crucial for comprehending the architectural preferences and choices made by institutions associated with the M.E.C.S. These findings set the stage for understanding the factors influencing architectural style choices in Anderson Hall.

Factors Influencing Anderson Hall Style Choices

Evidence 1:Funding on Campus Development

In the early years of Soochow University (1900-1927), the institution relied on funding sources such as educational grants, local community donations, and limited tuition fees. However, the primary financial support for campus development came from external donations (Wang, G. 2010).1909 President Anderson secured $20,000 in gold from the Lynchburg Court District Church during his visit to the United States. The funds were used for the construction of Anderson Hall, completed in 191 (Wang, G. 2010.p.122). These donations, typically from churches, were driven by specific missions and visions. Therefore, when selecting the architectural style for the campus, the university was inclined to consider the church's religious beliefs and missions, resulting in Anderson Hall's architectural style reflecting the church's mission and vision.

Evidence 2:Missionaries' Stylistic Preferences

As mentioned earlier, the early Christian educational institutions set up by missionaries in China, Japan, and Korea underwent significant development. The research also discusses the architectural preferences and doctrinal regulations of the M.E.C.S. The book "The Architectural Expression of Methodism: The First Hundred Years," which focuses on the architectural history of the Wesleyan tradition, provides clues about these aspects. By the 1830s, as the M.E.C.S. and its Sunday schools expanded, they focused more on architectural form. The growth of the denomination and the Gothic Revival movement, which emphasized medieval architectural styles, influenced this shift toward architectural distinctiveness. The M.E.C.S conservative aesthetic tendencies led to the adoption of two distinct architectural approaches:

"Classical or Gothic architectural styles were preferred in locations where professional architects were available, while in places without professional architects, the architecture was described as having an indistinct style" (Dolbey, G. W. 1964).

Clear architectural regulations play a crucial role in ensuring the consistency and quality of school buildings. In "The Educational Directory and Yearbook of China," it is noted that architectural regulations are highly desirable for school buildings established by missionaries, providing references from the Education Committee of England and Wales for architectural limitations in secondary and regular schools in China (The Educational directory of China. 1916).

During Soochow University's construction, particularly in designing Anderson Hall, the influence of the M.E.C.S and its architectural preferences and doctrinal regulations was evident. Such aligns with the university's commitment to both aesthetics and religious values. The decision to adopt a Western architectural style indicates the M.E.C.S's inclination towards Collegiate Gothic designs, as previously discussed, particularly in locations with access to professional architects.

Evidence 3:Influence of the Vanderbilt Connection

Nashville, Tennessee, housed the central headquarters of the M.E.C.S. The formal registration of Soochow University in this southern American city in 1901 signifies a profound institutional connection (Wang, G. 2010.p.88). However, this connection goes beyond the administrative record, extending to Vanderbilt University, also located in Nashville, which holds paramount importance in the narrative (Campus Land Use 2019, April 2). Vanderbilt University, established in 1873 by Bishop H.N. McTyeire of the M.E.C.S, was a pivotal institution for the training and development of missionaries. Distinguished Vanderbilt alums who assumed leadership positions at Soochow University include Y.J. Allen, a foreign board member, President Cline, and various faculty members, such as Qi Tianxi, R.D. Smart, J. Whiteside, E.V. Jones, T.C. Chao, and S.G. Brinkly (Xu, X. 1993).

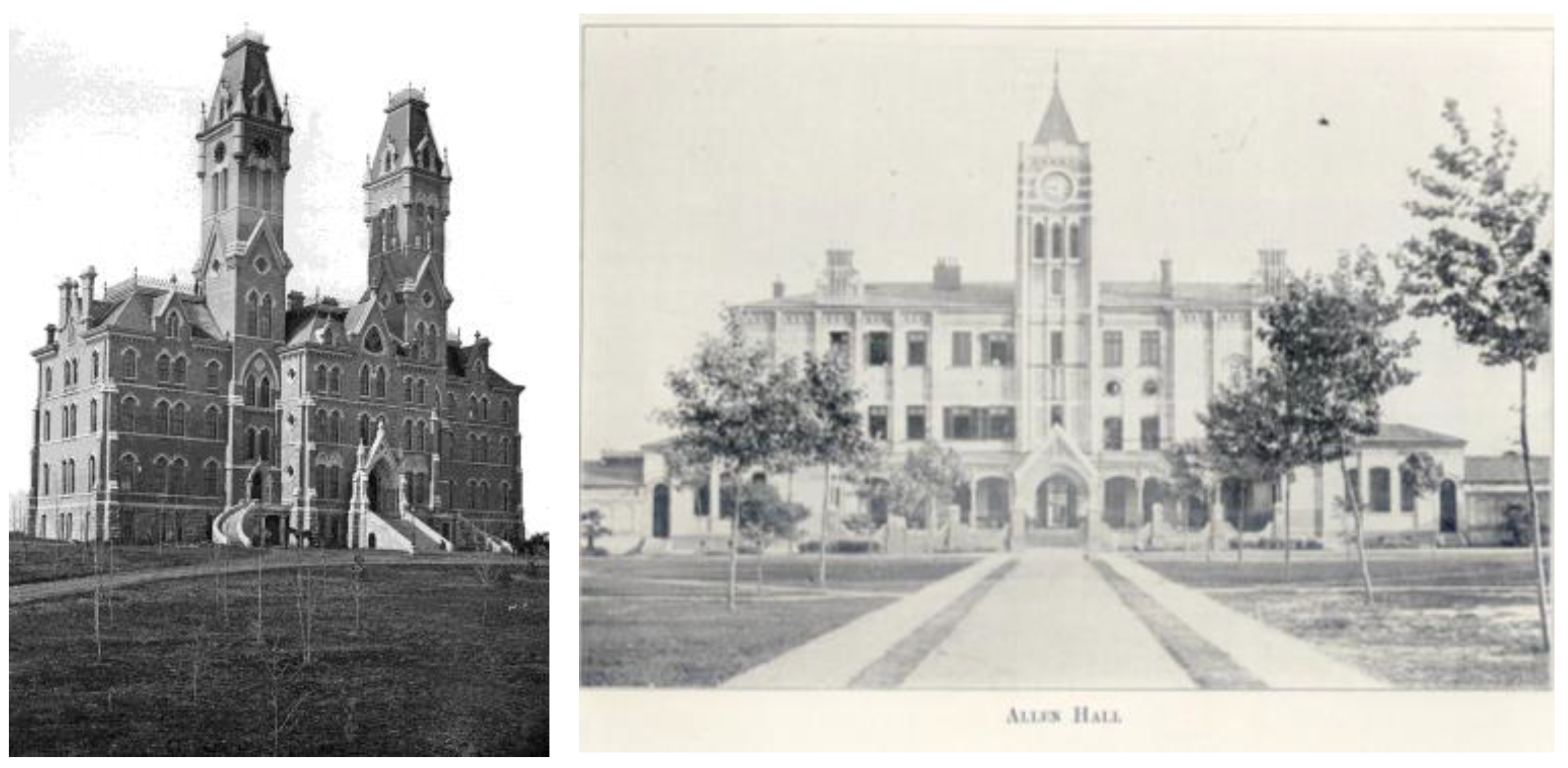

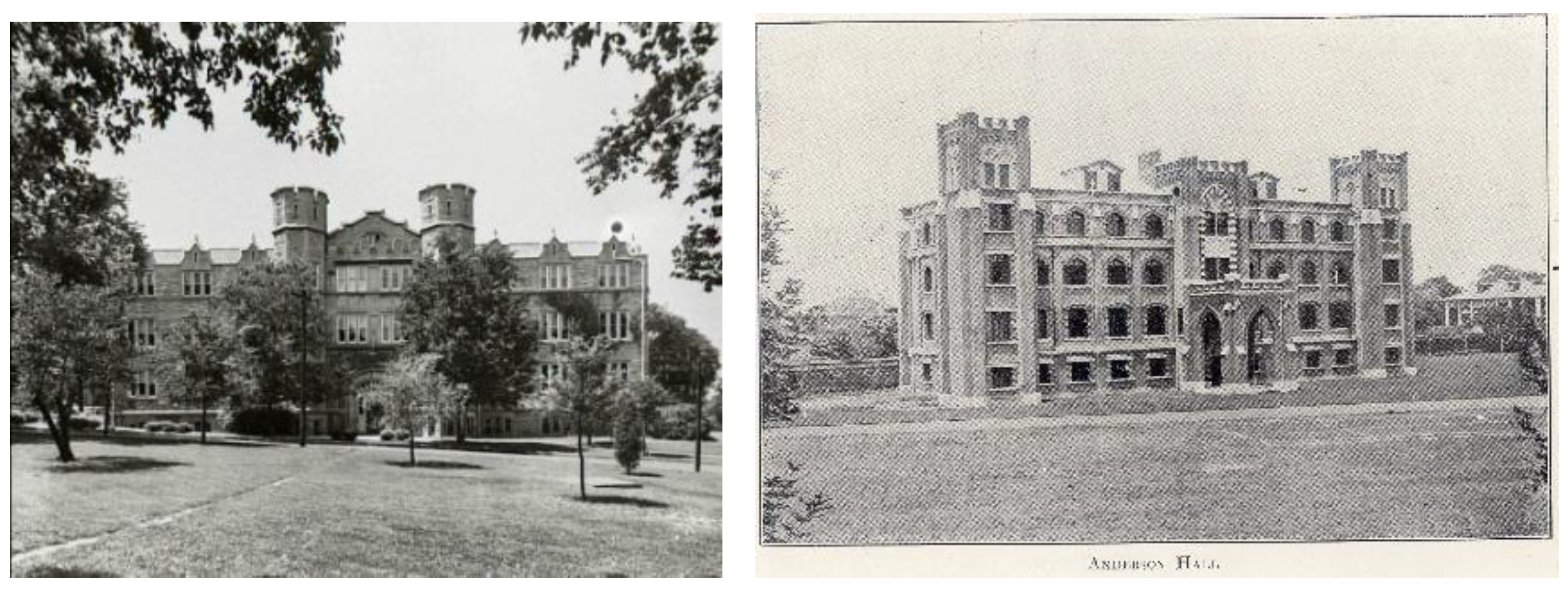

Owing to their shared educational background and pedagogical principles, the administrators and educators from Vanderbilt University, who joined the ranks of Soochow University, naturally sought to emulate their alma mater. This transference of educational philosophy and campus design served as the fulcrum for the Vanderbilt Connection, significantly impacting the architectural style and overall ambiance of Soochow University's campus. The architectural influence of the Vanderbilt Connection is evident in Kirkland Hall and Furman Hall at Vanderbilt University and Allen Hall and Anderson Hall at Soochow University (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These towers feature Collegiate Gothic elements like pointed arches and stained glass windows. This architectural influence permeates the broader campus aesthetics, thus shaping Soochow University's distinctive identity and architectural heritage.

Evidence 4:Role of Architects in Design Choices

Various architects and artisans from Western and Chinese backgrounds have left their imprint on the architectural landscape of Soochow University. Allen Hall, Soochow University's main building, is at the core of this architectural narrative, widely attributed to Atkinson & Dallas, a British architectural firm based in Shanghai (Wright, A. 1908). Despite the 1905 "China Educational Directory" praising Allen Hall as "built in the best style," it's noteworthy that the popular trend at the time, characterized by blending Collegiate Gothic and Colonial Revival elements, soon lost its appeal, as indicated by historical accounts. As W. B. Nance observed, this architectural style, including Queen Anne-style verandas, fell out of favor with Americans.

In tandem with the university's expansion, the construction of Anderson Hall from 1910 to 1912 perpetuated the tradition of the Collegiate Gothic Style. Subsequently, Cline Hall, erected between 1922 and 1924, marked a shift toward a simplified Gothic style. These structures symbolize the architectural evolution at Soochow University, reflecting the influence of architectural trends of their respective periods.

Historical records from the supervisory committee indicate the involvement of a British architect in the design of Anderson Hall, although the architect's identity remains unconfirmed

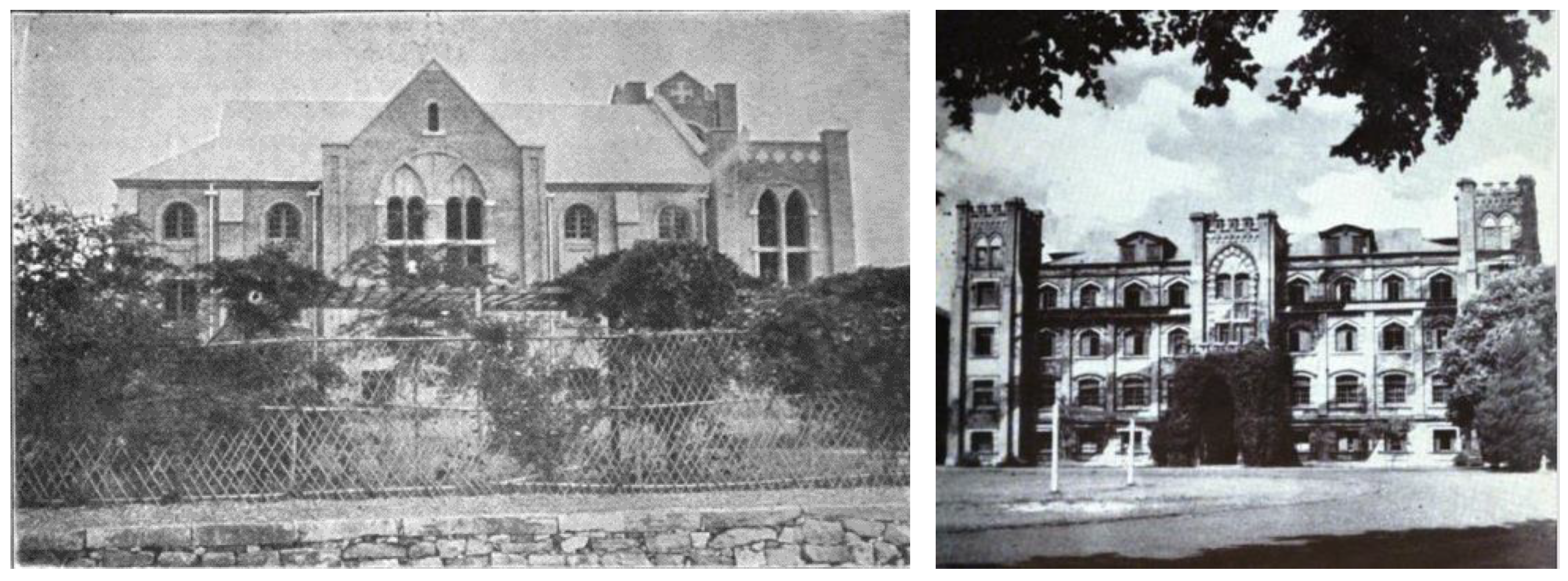

4. Historical records show that Chinese artisans constructed Anderson Hall and St. John's Church (

Figure 7). Local Chinese

5 builders actively created Anderson Hall; some even converted to Christianity during the project (Methodist Episcopal Church, South. B. of M. 1915). Moreover, according to W. B. Nance's articles, the British construction firm Algar & Co completed St. John's Church in 1915. W. B. Nance oversaw the final plans for St. John's Church (Church, M. E.1914). The proximity in construction timelines and the shared group of Chinese craftsmen suggest that the principal architect from Algar & Co. might have played a crucial role in designing Anderson Hall.

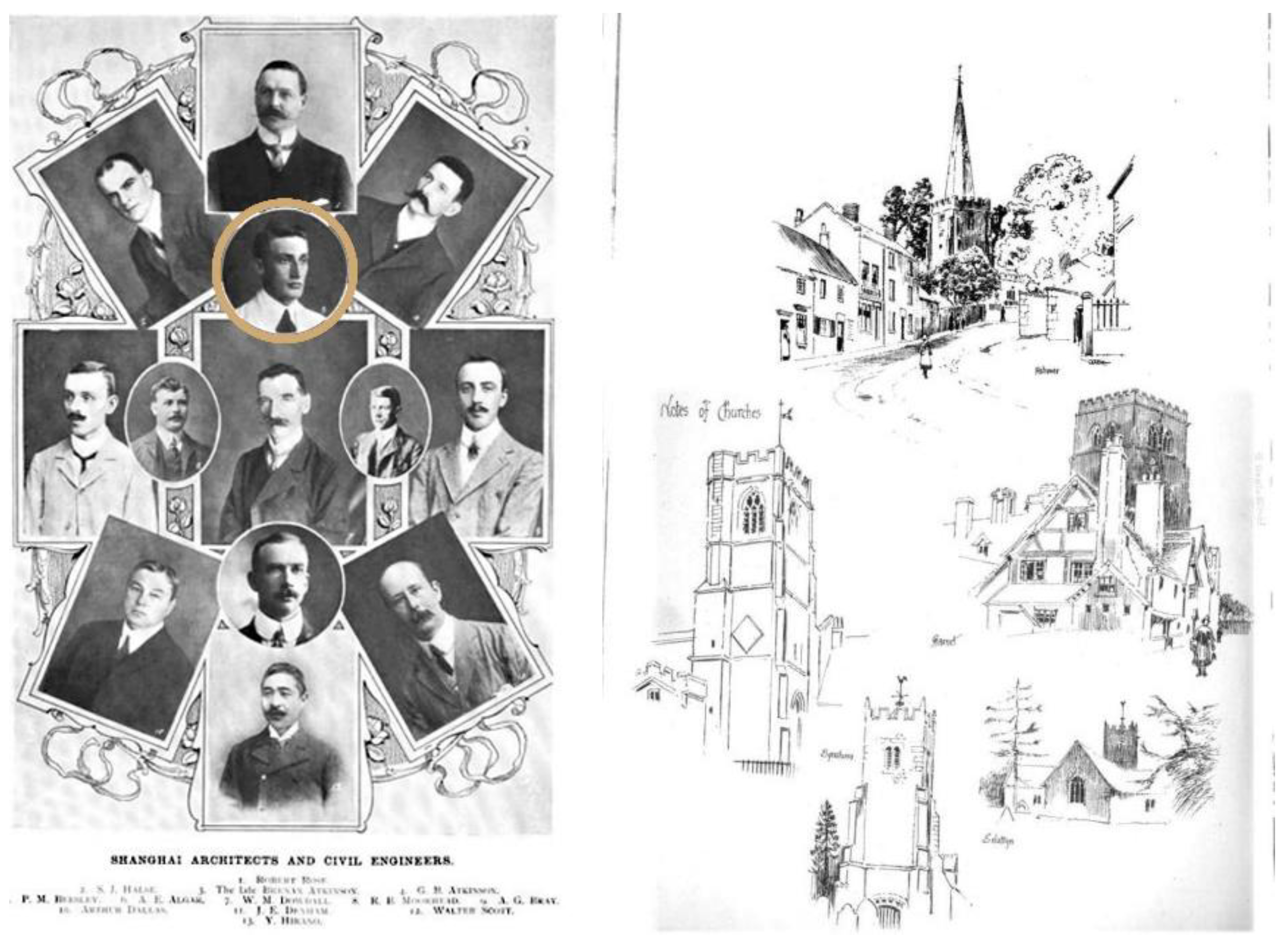

Further research reveals the critical role of Shanghai-based Algar & Beesley, a predecessor of Algar & Co, in shaping Soochow University's architectural landscape. The British architects of Algar & Beesley, particularly Beesly, a member of the British Architectural Society, significantly influenced the university's architectural heritage with his background in early British Gothic architecture

6. In the book 'The British Architects' that references Beesly, there are illustrations featuring a Tudor-style tower remarkably similar to the one in Anderson Hall (The British Architect.1898) (

Figure 8). These visual parallels strongly suggest English Architecture's influence. Beesly was a member of the Shanghai Architects (Wright, A. 1908) and the Young Men's Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.). This association with the Y.M.C.A. reflects a deeper connection to the region, suggesting that his architectural work extended beyond professional obligations. Additionally, historical records reveal that Beesly was an assistant at Atkinson & Dallas in 1902

7. This association with Atkinson & Dallas likely facilitated deeper involvement in Soochow University's architectural projects.

The 1915 China Continuation Committee Meeting records shed light on the architect selection process of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (M.E.C.S.). The meeting acknowledged the unlikelihood of establishing a dedicated architectural bureau for their missionary work. Instead, the committee concluded that a more practical solution would be to ensure the presence of reputable architectural firms with a strong interest in mission work by establishing branch offices in Shanghai (Church, M. E. June 1915). This fact aligns with the M.E.C.S.'s preference for architects with a deep commitment to missionary work and elevated status. In summary, it strongly suggests that British architect Beesly played a pivotal role in the design and construction of Anderson Hall at Soochow University.

Summary

The evidence underscores the pivotal role played by financial considerations in driving the design process. Financial constraints and the availability of funds were critical determinants in shaping Anderson Hall's architectural identity. Moreover, the stylistic preferences of the missionaries, deeply rooted in their cultural and religious ideals, profoundly impacted the architectural choices. This influence not only indicates a significant ideological imprint but also reflects the broader cultural dynamics of the era.

With its transcontinental reach, the Vanderbilt connection emerges as a prominent factor in the stylistic direction of Anderson Hall. This connection extended across borders and had a far-reaching impact on the development of Hall's architectural style. It exemplifies the interconnectedness of global networks and the diffusion of architectural trends.

Finally, the architects' pivotal role in translating these diverse influences into a tangible architectural masterpiece is evident. Their creative and strategic contributions were essential in bringing together the collective vision, translating it into structural elements, and achieving a harmonious fusion of form and function.

The careful analysis of these four interrelated factors equips us with a more profound insight into the complex processes that determined the architectural character of Anderson Hall. This knowledge is a robust foundation for further exploration in the subsequent chapters, where we will dissect the specific architectural elements that constitute the Hall's distinctive Gothic identity.

Collegiate Gothic Influence on Anderson Hall

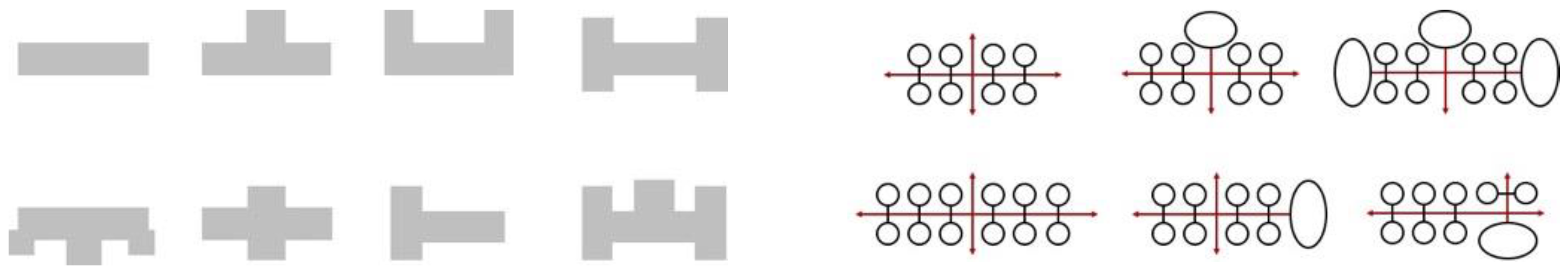

Soochow University pioneered educational architecture in China, notably by advancing the innovative "one-character" basic spatial prototype (

Figure 9). The architectural design of Anderson Hall prominently reflects this visionary approach.

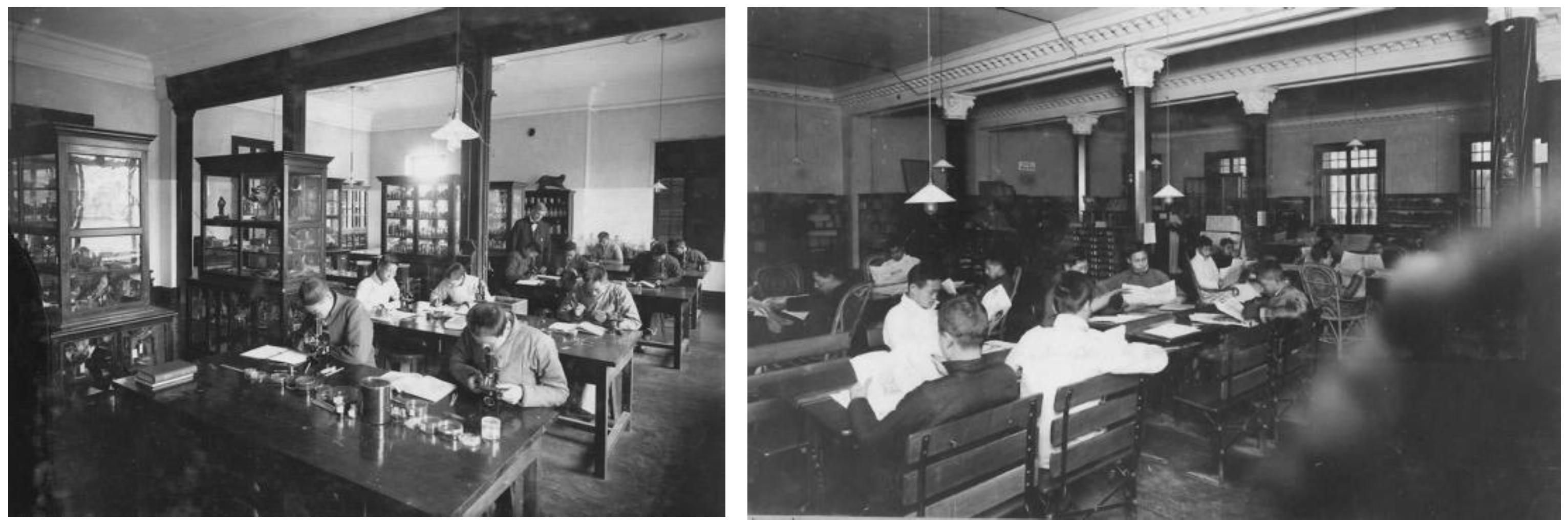

After the completion of Anderson Hall, the library gradually expanded into the northern section of the building; between 1921 and 1924, the library's growth extended to encompass the entire second floor of Anderson Hall, resulting in a separation of spaces for reading and book storage (

Figure 10). In the case of Anderson Hall, this meant that its architectural type, functions, and style became tangible expressions of this innovative pedagogy. Additionally, special functions within Anderson Hall, such as administrative offices, study areas, and literary societies, contributed to the creation of distinctive spatial forms both internally and externally.

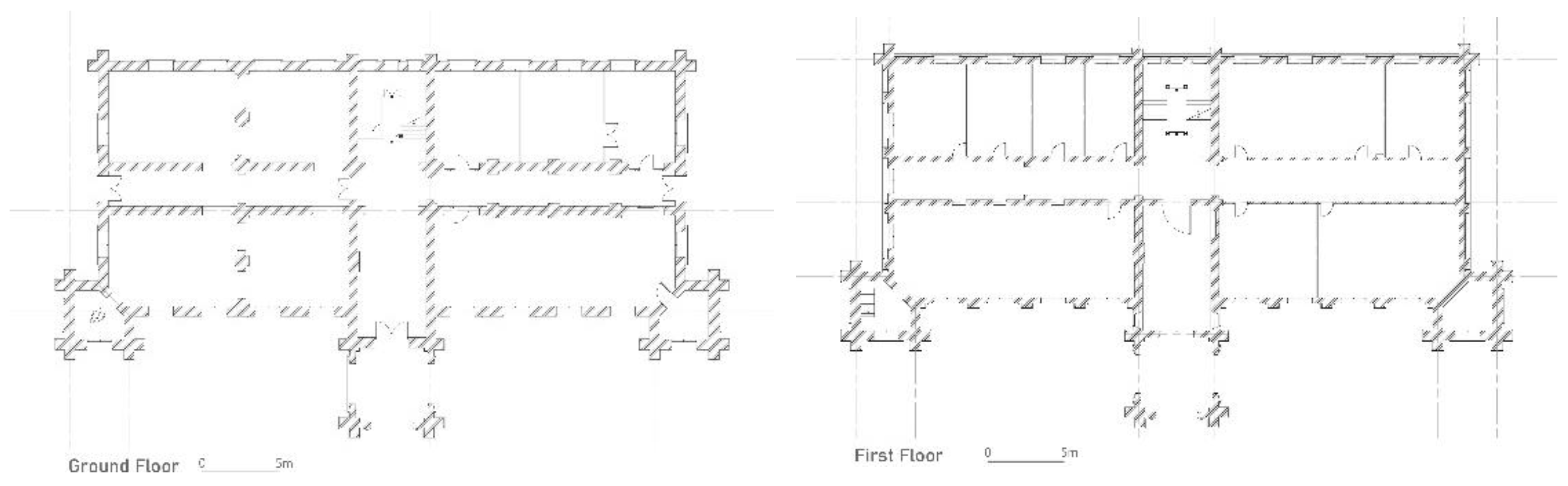

Architectural Plan Characteristics

With a central entrance symmetrically positioned along the longitudinal façade, Anderson Hall achieves an aesthetically balanced external appearance. The main entrance thoughtfully aligns with the central staircase, creating a harmonious and functional focal point.

Of particular significance is the internal arrangement of Anderson Hall. Each floor plan is segmented by intersecting corridors, establishing a continuous circulation system within the building (

Figure 11). These corridors serve a dual purpose: organizational hubs and circulation pathways. They occupy a substantial portion of each floor's total area, typically 20-30%, optimizing functional space and enhancing natural light and ventilation (Pan, Y., & Chen, X. 2021).

This architectural ingenuity within Anderson Hall exemplifies its innovative design. As the second building in Soochow University's development, it closely aligns with its evolving pedagogical philosophies and spatial requirements. It established itself as a central and pivotal structure in the institution's architectural heritage by adopting a relatively purer Collegiate Gothic style.

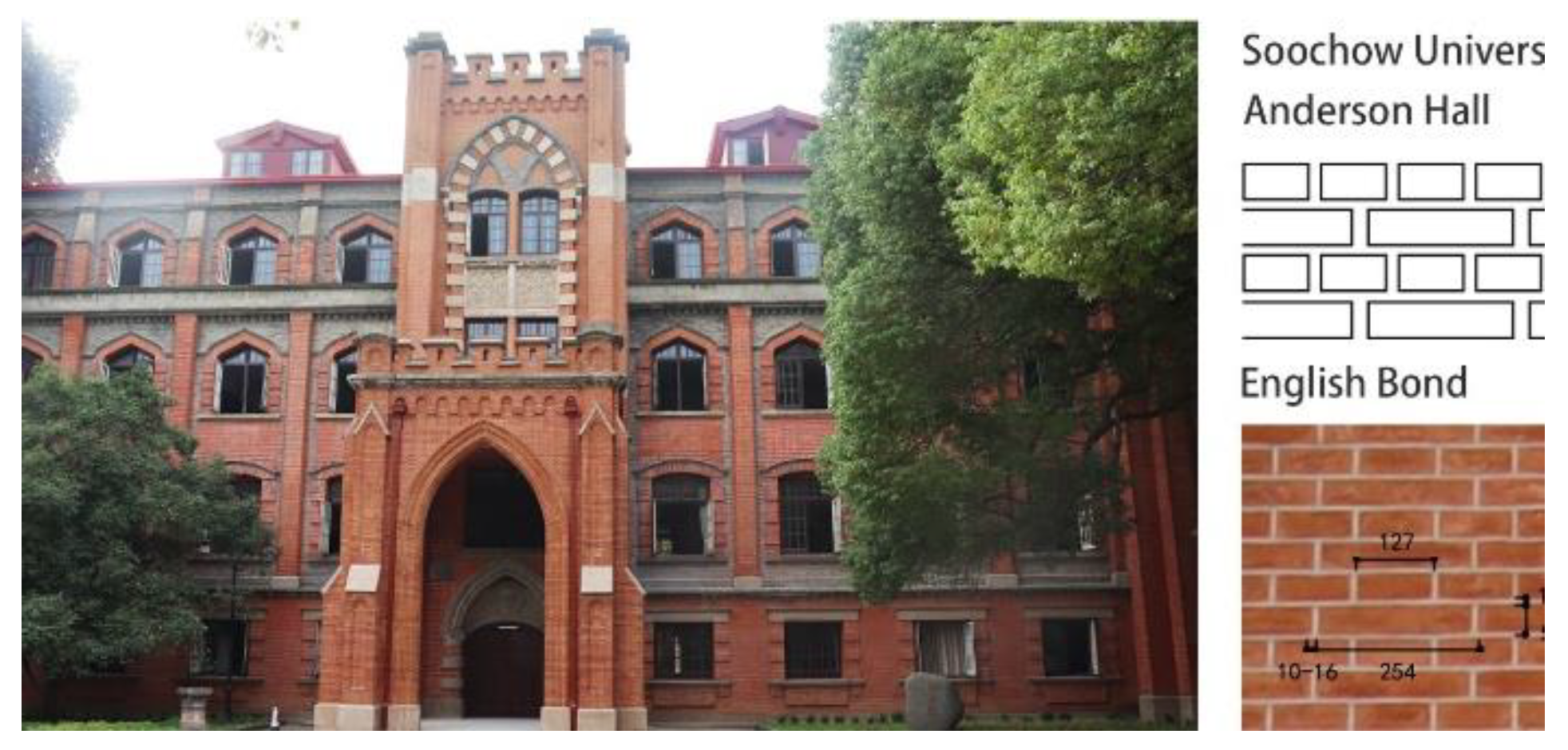

Structural Features

The unique structural features and innovative use of building materials distinguish Anderson Hall. It primarily incorporates a blend of red and blue bricks, departing from the traditional use of blue bricks. Christian architecture widely embraced red bricks during the 1930s (Pugin, A. W. N. 1841), and late Qing Shanghai witnessed the establishment of mechanized brick and tile factories. These developments heralded the era of modern red brick production (Shu, C. X.et al.2017). The collaboration of brick columns and arches is pivotal in sharing the load-bearing functions of the walls, resulting in a distinct cross-shaped structure at the building's corners.

Furthermore, the dimensions of Anderson Hall's red bricks closely resembled the prevalent measurements in Shanghai, which were 254*127*44 millimeters, deviating from the typical size of blue bricks at 254*127*50 millimeters (

Figure 12). Given the close cultural exchanges and railway connections between Suzhou and Shanghai (Shu, C. X., & Coomans, T. 2020), one can plausibly infer that Shanghai transported the red bricks used in Anderson Hall to Suzhou (Pan, Y., & Chen, X. 2021). This transportation of materials reflects the process of localizing Western-style architectural materials in regions like Shanghai and Suzhou. Moreover, the application of English-style masonry distinguishes the structure of Anderson Hall. It underscores the profound influence of Western architectural culture on Suzhou's building practices.

Adopting a Western-style roof structure in Anderson Hall provides the building with enhanced architectural freedom and spatial design flexibility, emphasizing the assimilation of Western architectural technology and construction (

Figure 13).

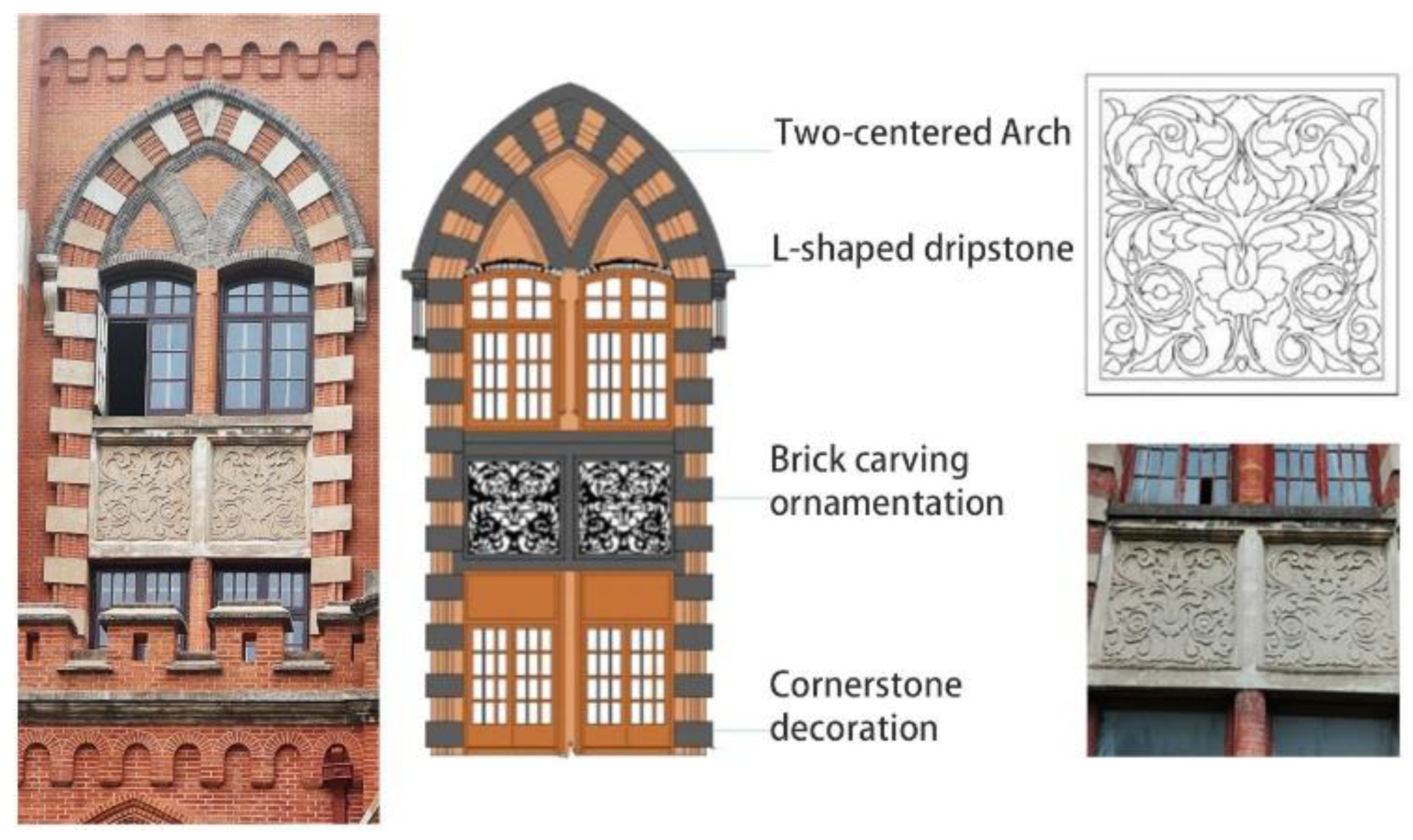

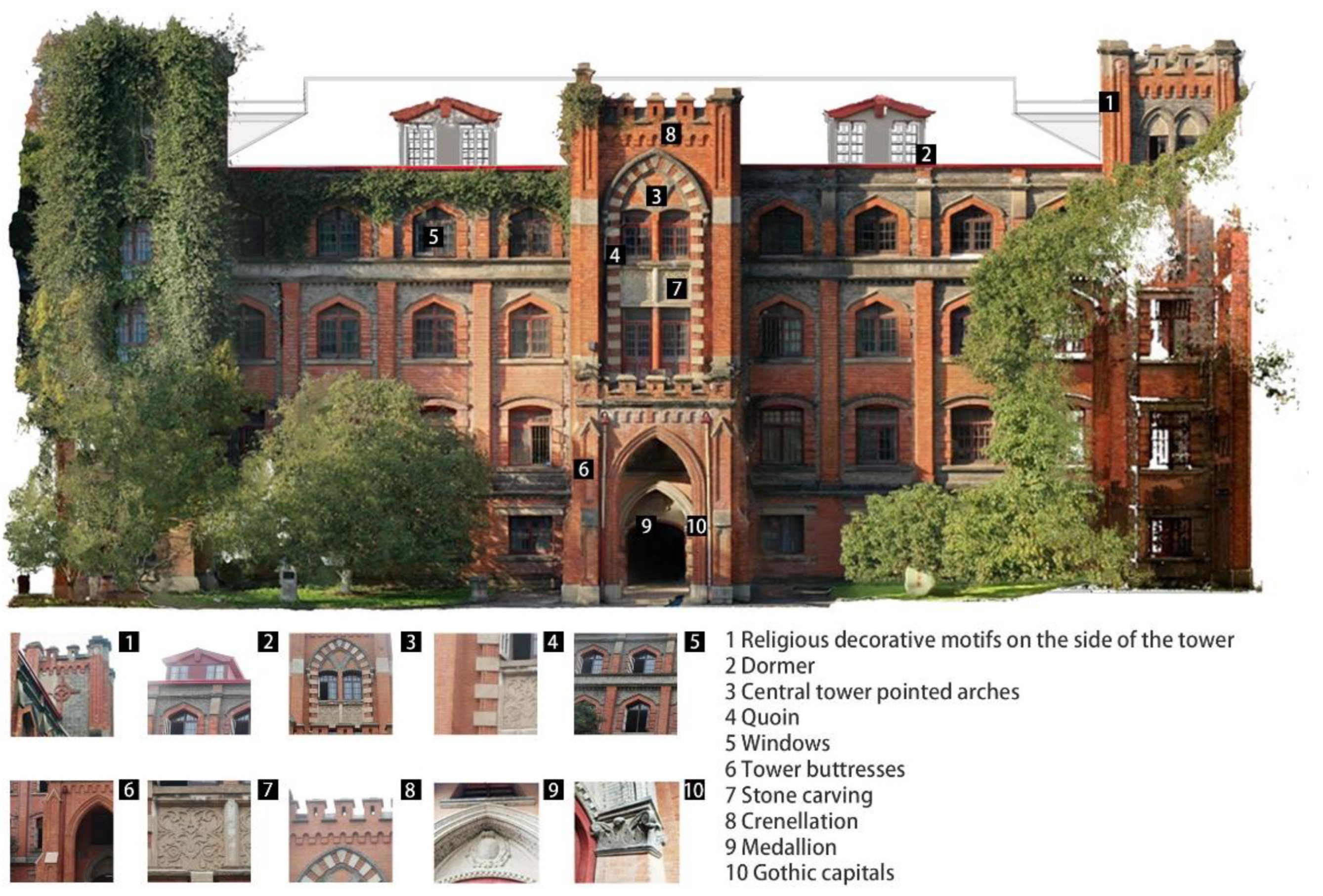

Facade Characteristics

The eastern façade of Anderson Hall proudly exhibits a quintessential Collegiate Gothic architectural feature. Three towering structures, graced with crenelated parapets, evoke the imagery of medieval European fortifications, infusing the tower with a palpable sense of grandeur. The central entrance commands immediate attention, serving as the focal point of the facade. It boasts a majestic porch featuring three twin-centered pointed arches, each towering to an impressive height of approximately 6 meters and spanning a breadth of 2.5 meters. Artisans adorned these arches with intricate stone carvings and intricate dentil molding, a testament to the exceptional craftsmanship invested in their creation (

Figure 14).

A commanding equilateral particularly distinguishes the central entryway pointed arch (

Figure 15). Nested within this imposing arch are two smaller pointed arches, contributing to the doorway's overall architectural intricacy. The pointed arch windows on the summits of the towers flanking the building's facade correspond with the tapered arch design of the central tower. The vertical progression of window designs on each level of the gloss imparts a sense of ascension and visual grandeur characteristic of Gothic architecture, ultimately contributing to the overall harmony and unity of the facade.

Of profound significance, the northern and western facades of the tower structures prominently feature the symbolism of the Christian faith, displaying the "Celtic cross." These faith-inspired elements underscore the deep spiritual and cultural connections interwoven with the architectural features of Anderson Hall (

Figure 16).

Conclusion

The emergence of Collegiate Gothic architecture in the first half of the 20th century in East Asia represents a profound intersection of culture, technology, values, and education. This architectural style transcends mere bricks and stones; it encapsulates the dynamic interplay between societal needs and the expression of values. Through a closer examination of the pathways of American missionaries like Lambuth, who traversed East Asia, this study presents fresh perspectives on the M.E.C.S missionary background and the evolution of educational endeavors across the region. The institution's unwavering commitment to religious values, educational equality, and global connectivity manifests in the elegant fusion of Gothic architectural aesthetics and profound Christian symbolism seen in Anderson Hall.

The investigation of missionary-driven architectural styles has unveiled the profound influence of religious and cultural elements on architectural design. In the section discussing the factors influencing the design choices of Anderson Hall, we presented four pivotal pieces of evidence: campus development funding, the stylistic preferences of missionaries, the influence of the Vanderbilt connection, and the architects' decisive role. These factors collectively crafted the distinctive design of Anderson Hall, amalgamating a myriad of cultural and historical elements.

Through our comprehensive case study of Anderson Hall at Soochow University, we meticulously dissected the educational context, architectural plan characteristics, structural features, and facade attributes. This case study exemplifies the theories and concepts in this paper, affording a profound understanding of the intricate interplay between Collegiate Gothic architecture and missionary education.

Fundamentally, our research underscores the critical role of architecture as an educational and cultural medium within university campuses. It emphasizes how missionary education has left an indelible mark on architectural styles and design, enriching our comprehension of university campuses' broader historical and cultural context. We are confident that this study will stimulate further research at the intersection of missionary education and architectural styles, contributing to the advancement of our understanding regarding the evolution of university campuses and the educational ideologies they represent. Furthermore, this research holds significant implications for the broader field of heritage preservation, underscoring the critical importance of comprehending the intricate interplay between culture and architecture in safeguarding our cultural legacies.

Notes

| 1 |

The Methodist Episcopal Church South (M.E.C.S) was the American Methodist denomination resulting from the 19th-century split over the issue of slavery in the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) in 1844. It reunited with the MEC and other churches in 1939 to form the Methodist Church (U.S.) |

| 2 |

Walter Russell Lambuth:Lambert's son, who grew up in Shanghai and then returned to the U.S. to study, went to Soochow in 1877 after receiving his M.D. In 1886, he was sent to western Japan to establish the Methodist Episcopal Church South. |

| 3 |

After 1920, Yoon Chi-ho became the director of the foundation of the Chosen Christian College and Ewha Womans University . |

| 4 |

Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education inAsia, RG011-269-4285. |

| 5 |

“...The Chinese constructor played a prominent part in making the edifice possible. He was converted while building Anderson Hall for the Soochow University. This church is largely his thank offering, for he undertook the contract, determined not only not to make a cent out of it, but even to contribute all that he could in addition.” (Methodist Episcopal Church, South. B. of M. 1915.p.553) |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

The Directory and Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Malay States, Siam, Netherlands India, Borneo, the Philippines, and etc (1902). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Daily Press Office. (p.261,752.). |

References

- Cai, L., & Deng, Y. (2011). The Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the Modern Chinese Protestant Colleges. Building Science, 27(1), 106–110. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., & Deng, Y. (2012). Campus construction and Collegiate Gothic architecture of the modern University of Shanghai for Science and Technology. Sichuan Building Science, 38(1), 213–217.

-

Campus Land Use / Master Planning History at Vanderbilt. (2019, April 2). Vanderbilt University. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/futurevu/history/.

- Chapman, M. P. (2006). American Places: In Search of the Twenty-First Century Campus. A.C.E./Praeger Series on Higher Education. Greenwood Publishing Group, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06825.

- Church, M. E., Methodist Episcopal Church, S., & China, M. E. C. C. C. (1914). The China Christian Advocate (January 1916). In Google Books. Methodist Publishing House in China. .https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=xBlBAQAAMAAJ.

- Church, M. E., Methodist Episcopal Church, S., & China, M. E. C. C. C. (June 1915). The China Christian Advocate.In Google Books. Methodist Publishing House in China. https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=xBlBAQAAMAAJ.

- Coulson, J.et al. (2015). University planning and architecture: The search for perfection. Routledge.

- Dolbey, G. W. (1964). The architectural expression of Methodism: the first hundred years. The Epworth Press.

- Emoto, H. (2017). The French Oxford in Modern America: A historical inquiry into the collegiate gothic movement in the late 19th century–part I.Journal of Architecture Planning, Architectural Institute of Japan,82(732), 539-545.

- General, M. E. C. S. (1901). Missionary issues of the twentieth century.

- Hong, M. (2020).A Study on the Beginning of Japan Mission and Early Mission Work by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South(1886~1892): Focusing on Mission Work of W. R. Lambuth. Korean Journal of Christian Studies,116, 191-226.

- Hu, X. (1985). Supplementary study on the establishment process of Soochow University: Cultivating, nurturing, and incorporating Eastern and Western education. Journal of Soochow University, 4, 113–115. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Y. (2006). study on gothic design for the elevation composition of modern buildings in Ewha Womans University. Master's thesis, Hongik University.

- Kim, B. W., & Kim, Y. J. (2019). Accommodating the Collegiate Gothic Style in Modern School Buildings of Korea. Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea Planning & Design, 35(11), 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Kong, N., & Liu, S. (2020). Cultural Interpretation of the Architectures in Missionary Universities of Modern China: A Case Study of Yates Hall at the University of Shanghai. Journal of University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 42(3), 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2022), Study on The Evolution of Spatial Pattern of Soochow University Old Campus(1850-1952). Master's thesis, Soochow University.

- List of materials | Korean History Database. (2018), Diary of Yun Chi Ho, November 15, 1917. National History Compilation Committee.https://db.history.go.kr/item/level.do?itemId=sa&levelId=sa_030_0020_0110_0150&types=o.2023-11-6.

- Lutz, J. G. (1958). Seven Histories of Christian Colleges in China - Seven Histories of Christian Colleges in China. Shantung Christian University (Cheeloo). By Charles H. Corbett. New York: United Board for Christian Colleges in China, 1955. 281. Cloth, $3.00; paper, $2.00. - Hangchow University: A Brief History. By Clarence Burton Day. 1955. 183. - St. John's University, Shanghai, 1879–1951. By Mary Lamberton. 1955. 261. - Soochow University. By W. B. Nance. 1956. 163. - Fukien Christian University: A Historical Sketch. By Roderick Scott. 1954. 138. - Ginling College. By Mrs. Lawrence Thurston and Ruth M. Chester. 1955. 171. - Hwa Nan College: The Women's College of South China. By L. Ethel Wallace. 1956. 164. The Journal of Asian Studies, 18(1), 132–134. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. (2012). The Study of the Enterprise of Methodist Episcopal Church, South in China (1848-1939). Doctoral dissertation, Shandong University.

- Methodist Episcopal Church, South. B. of M. (1915). Missionary Voice. In Google Books. Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Board of Missions. https://books.google.com/books?

- Morgan, W. (1989). Collegiate Gothic The Architecture of Rhodes College.

- Nate. (2020, February 15). Chosen Christian College (1910s-1950s). Colonial Korea. https://colonialkorea.com/2020/02/15/chosen-christian-college-1910s-1950s/#comments.2020-2-15/2023-11-6.

- Pan, Y., & Chen, X. (2021). Creating an American Methodist college in China: A building history of Soochow University, 1900–1937. In History of Construction Cultures Volume 1 (pp. 77-84). C.R.C. Press.

- Pugin, A. W. N. (1841). The true principles of pointed or Christian architecture are set forth in two lectures delivered at St. Marie's, Oscott. J. Weale.

- 25. Rikkyo Gakuin Archives Center (立教学院史資料センター編). (2007). History of Rikkyo University(立教大学の歴史). Rikkyo.repo.nii.ac.jp(東京: 立教学院史資料センター). [CrossRef]

- Shu, C. X., & Coomans, T. (2020). Towards modern ceramics in China: Engineering sources and the Manufacture Céramique de Shanghai. Technology and Culture, 61(2), 437-479. [CrossRef]

- Shu, C. X.et al. (2017). China's brick history and conservation: laboratory results of Shanghai samples from 19th to 20th century. Construction and Building Materials, 151, 789-800. [CrossRef]

- The British Architect: A Journal of Architecture and the Accessory Arts. (1898). In Google Books. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_British_Architect/dUkSAQAAMAAJ?hl=zh-CN&gbpv.

- The Educational Directory of China. (1916). In Google Books. Shanghai: Educational Directory of China Publishing. https://books.google.com/books?id=JJwZAQAAIAAJ.

- Wang, G. (2010). Selected historical materials of Soochow University.Suzhou University Press.

- Williams Jr, M. O. (1993). From mission to annual conference: the work of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in China, 1848-1886. Methodist History, 31(3), 148-161.

- Wright, A. (1908). Twentieth-century impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other treaty ports of China: their history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (Vol. 1). Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company.

- Wright, A. (1908). Twentieth-century impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other treaty ports of China: their history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (Vol. 1). Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company.

- Xu, X. (1993). A Southern Methodist mission to China: Soochow University, 1901-1939. Middle Tennessee State University.

- Ziolkowski, J. M. (2018). The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Open Book Publishers.

Figure 1.

Campuses Established by the Methodist Episcopal Church in China. (Source: Li, X. 2022).

Figure 1.

Campuses Established by the Methodist Episcopal Church in China. (Source: Li, X. 2022).

Figure 3.

Left, Underwood Hall at the Chosen Christian College. Murphy & Dana initially imagined the main building in a perspective drawing. Note the clock on the facade, which was absent from the built version of the building. Right, The University of Chicago did not implement an early design architectural drawing for the George Herbert Jones Laboratory. Both buildings feature a crenelated parapet and a horizontal elongated layout. (Source: Left, Christian Gateway to Asia (1918),

https://colonialkorea.com/2020/02/15/chosen-christian-college-1910s-1950s/; Right, University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center, =

https://photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu/db.xqy?one=apf2-04547.xml).

Figure 3.

Left, Underwood Hall at the Chosen Christian College. Murphy & Dana initially imagined the main building in a perspective drawing. Note the clock on the facade, which was absent from the built version of the building. Right, The University of Chicago did not implement an early design architectural drawing for the George Herbert Jones Laboratory. Both buildings feature a crenelated parapet and a horizontal elongated layout. (Source: Left, Christian Gateway to Asia (1918),

https://colonialkorea.com/2020/02/15/chosen-christian-college-1910s-1950s/; Right, University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center, =

https://photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu/db.xqy?one=apf2-04547.xml).

Figure 4.

The M.E.C.S. routes and the representative territories and universities in the Collegiate Gothic style. (Source: Drawing by Jiabao He. The base map from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Catalog of investments in the Kingdom of God: the constructive program of the missionary centenary [M]. Nashville, Tenn.: Centenary Commission, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, [1919])

Figure 4.

The M.E.C.S. routes and the representative territories and universities in the Collegiate Gothic style. (Source: Drawing by Jiabao He. The base map from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Catalog of investments in the Kingdom of God: the constructive program of the missionary centenary [M]. Nashville, Tenn.: Centenary Commission, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, [1919])

Figure 5.

Left, Vanderbilt University, Kirkland Hall(built in 1875). Right, Soochow University, Allen Hall (built in1901-1904). The spires and towers in the design of both buildings share certain similarities. (Source: Left,

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/about/history/. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-271-4310)

Figure 5.

Left, Vanderbilt University, Kirkland Hall(built in 1875). Right, Soochow University, Allen Hall (built in1901-1904). The spires and towers in the design of both buildings share certain similarities. (Source: Left,

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/about/history/. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-271-4310)

Figure 6.

Left, Vanderbilt University, Furman Hall (built in 1907). Right, Soochow University, Anderson Hall (built in 1910-1912). Both buildings feature a crenelated central tower. Furman Hall primarily incorporates Korean stone, whereas Anderson Hall predominantly features red bricks. (Source: Left, Van Irwin Jr. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives photo archive image P.A. B.L.D.FURM.29.

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/trees/furman-hall-shumard-oak/. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-271-4310)

Figure 6.

Left, Vanderbilt University, Furman Hall (built in 1907). Right, Soochow University, Anderson Hall (built in 1910-1912). Both buildings feature a crenelated central tower. Furman Hall primarily incorporates Korean stone, whereas Anderson Hall predominantly features red bricks. (Source: Left, Van Irwin Jr. Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives photo archive image P.A. B.L.D.FURM.29.

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/trees/furman-hall-shumard-oak/. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-271-4310)

Figure 7.

Left, St.John's Church (built in 1915). St. John's Church is situated close to Soochow University. St. John's Church and Anderson Hall's coexistence represents an exciting juxtaposition of architectural styles and historical significance within the university's vicinity. Right, Anderson Hall (built in 1910-1912). (Source: Left, Missionary Voice.American, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Board of Missions,1915.

https://www.google.com.hk/books/edition/Missionary_Voice/8xfPAAAAMAAJ?kptab=overview. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-415-5874-5002.).

Figure 7.

Left, St.John's Church (built in 1915). St. John's Church is situated close to Soochow University. St. John's Church and Anderson Hall's coexistence represents an exciting juxtaposition of architectural styles and historical significance within the university's vicinity. Right, Anderson Hall (built in 1910-1912). (Source: Left, Missionary Voice.American, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Board of Missions,1915.

https://www.google.com.hk/books/edition/Missionary_Voice/8xfPAAAAMAAJ?kptab=overview. Right, Special Collections, Divinity Library, Yale University, United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, RG011-415-5874-5002.).

Figure 8.

Left, The image titled "Shanghai Architects and Civil Engineers" depicts P.M. Beesley as the fifth individual among thirteen people. Right, The book "British Architects" mentions P.M. Beesley and, in subsequent pages, mainly features crenelated tower designs. (Source: Left, Wright, A., Cartwright, H.A. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and Other Treaty Ports of China: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. English: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company. (p.622). Right, The British Architect: A Journal of Architecture and the Accessory Arts. English. (1898) (p.84).)

Figure 8.

Left, The image titled "Shanghai Architects and Civil Engineers" depicts P.M. Beesley as the fifth individual among thirteen people. Right, The book "British Architects" mentions P.M. Beesley and, in subsequent pages, mainly features crenelated tower designs. (Source: Left, Wright, A., Cartwright, H.A. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and Other Treaty Ports of China: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. English: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company. (p.622). Right, The British Architect: A Journal of Architecture and the Accessory Arts. English. (1898) (p.84).)

Figure 9.

Left, plan types of Soochow University buildings.Right, the spatial structure of the plan. (Source: Pan, Y., & Chen, X. 2021)

Figure 9.

Left, plan types of Soochow University buildings.Right, the spatial structure of the plan. (Source: Pan, Y., & Chen, X. 2021)

Figure 10.

Left, Class in Botany at Anderson Hall. Right, Library at Anderson Hall. (Source: Left, Mission Photograph Album - China #13 page 0093, original photo title:86456 Class in Botany. Soochow. (about 1918); Right, Mission Photograph Album - China #13 page 0096, original photo title:86462 Library at Soochow University.)

Figure 10.

Left, Class in Botany at Anderson Hall. Right, Library at Anderson Hall. (Source: Left, Mission Photograph Album - China #13 page 0093, original photo title:86456 Class in Botany. Soochow. (about 1918); Right, Mission Photograph Album - China #13 page 0096, original photo title:86462 Library at Soochow University.)

Figure 11.

Left, Ground Floor of Anderson Hall.Right, First Floor of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Suzhou Jicheng Conservation Co. and Soochow University students 2019.)

Figure 11.

Left, Ground Floor of Anderson Hall.Right, First Floor of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Suzhou Jicheng Conservation Co. and Soochow University students 2019.)

Figure 12.

Anderson Hall Red Brick Detail. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 12.

Anderson Hall Red Brick Detail. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 13.

Anderson Hall's interior roof structure. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He and Xu Gao.)

Figure 13.

Anderson Hall's interior roof structure. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He and Xu Gao.)

Figure 14.

The arch on the east elevation of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 14.

The arch on the east elevation of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 15.

The decorations on the central pointed arch. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 15.

The decorations on the central pointed arch. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He.)

Figure 16.

The decorations on the east elevation of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He. Soochow University students, supervised by Shiruo Wang in 2020, completed the model scanning work.)

Figure 16.

The decorations on the east elevation of Anderson Hall. (Source: Drawings by Jiabao He. Soochow University students, supervised by Shiruo Wang in 2020, completed the model scanning work.)

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).